In contemporary medical practice, we expect our clinical actions to reflect the best and most current evidence. In many cases, however, the evidence available to us is weak or irrelevant. In their investigation, Berghella and colleagues set out to assess the quality of evidence in the setting of transvaginal cervical cerclage by reviewing the published data on selected perioperative strategies. They elected to perform a systematic review, as opposed to a narrative review (a simple opinion piece), because this approach follows an explicit process designed to limit bias and random error in the interpretation of scientific research.

The studies they analyzed vary from observational investigations to randomized trials, generating considerable heterogeneity in the data. Therefore, it would not have been feasible or appropriate for them to combine the results in a quantitative review (ie, meta-analysis). Their solution: to limit the analysis to a qualitative systematic review.

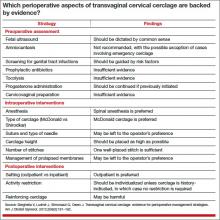

The term “systematic review” implies that investigators have an accurate and comprehensive understanding of existent data, with each study representing one contribution to a much larger body of knowledge. Over the years, Berghella and colleagues have contributed extensively to the literature on cervical cerclage and are well qualified to provide an analytic framework for the flood of published information on this practice. Although they focused primarily on how to perform cerclage, a discussion of when to perform cerclage cannot be separated from any consideration of efficacy.

When, exactly, is cerclage indicated?

The original indication for cerclage, established more than 50 years ago, required both a history of second-trimester loss and asymptomatic cervical changes in the current pregnancy. Since then, many cerclages have been performed on the basis of history alone or on current cervical changes regardless of history. However, the most recent professional guidelines reconfirm that any cerclage procedure should be supported by both historical and contemporaneous findings.1,2

Investigators have demonstrated that the measurement of cervical length by transvaginal ultrasound should generally be an integral part of clinical evaluation for asymptomatic cervical changes. Indeed, sonographic assessment has emerged as a tool capable of reducing “overcall” and unnecessary intervention.3 On the other hand, a meta-analysis of four randomized trials of ultrasound-indicated cerclage found it to be beneficial in women with a short cervix only if they also had a history of preterm delivery.4

In addition, randomized trials have documented a benefit for cerclage in two other clinical contexts:

- Results from a secondary analysis of data from a large randomized trial published in 1993 suggest that elective cerclage can be based on history alone in women with three or more second-trimester losses or preterm births.5

- Authors of a randomized trial published in 2003 suggested that women with advanced cervical changes, such as dilatation of the external os with exposure of the fetal membranes, may benefit from “emergency” cerclage even in the absence of a prior preterm delivery.6

How the data were analyzed

The data included in the review were analyzed separately, according to three widely accepted indications for cerclage:

- history-indicated: a history of three or more second-trimester losses and/or preterm births

- ultrasound-indicated: ultrasonographic detection of a cervical length of less than 25 mm, as measured by transvaginal ultrasound, in a woman with a history of second-trimester loss or preterm birth

- physical-examination–indicated: physical examination (manual or with a speculum) that confirms a dilated cervix.

Granted, this terminology can be confusing, as in the case of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, which includes aspects of the patient’s history. Moreover, I doubt that the studies included in this analysis always adhered to these definitions. The heterogeneity of the study population and the ambiguity of these definitions may limit the applicability of findings. In fact, they constitute the major (albeit practically unavoidable) limitation of this review.

The optimal approach to subclinical infection is unclear

Although there is a consensus that overt intra-amniotic infection is an absolute contraindication to cerclage, the implications of subclinical intra-amniotic infection in asymptomatic women are unclear. About 50% of women considered for emergency cerclage are likely to have intra-amniotic infection.7 An ongoing randomized trial is expected to elucidate the benefit of precerclage amniocentesis in such cases.

The sonographic detection of sludge in the amniotic fluid also has been associated with intra-amniotic infection. However, after analyzing the data, Berghella and colleagues did not find adequate justification for amniocentesis in this setting. A more practical question might be whether cerclage is advisable at all when sludge is present. Data from a recently reported abstract suggest that the presence of sludge increases the likelihood of early preterm birth independent of cervical length.8

Other gray areas

Another absolute contraindication to cerclage is the presence of painful uterine contractions in a woman exhibiting cervical change. The study findings seemed to imply that when uterine contractions are detected via tocodynamometric monitoring but are not experienced by the patient, cerclage may be appropriate. In my opinion, this issue represents another open clinical question.