Women with a history of spontaneous PTB undergo screening by transvaginal cervical-length assessment. Typically, the first measurement is obtained at the time of the fetal anatomic survey (18–22 weeks), when the lower uterine segment is sufficiently developed to accurately measure the cervix. We perform serial cervical-length assessment every 1 or 2 weeks until 28 weeks’ gestation in women with a prior early spontaneous PTB (<34 weeks), those with a history of recurrent PTB, and those who have an initial short cervix. Serial monitoring has been shown to increase the prediction of spontaneous PTB in high-risk women.14

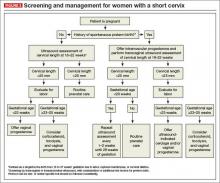

See the algorithm presented in (FIGURE 3) for the screening and treatment of women with singleton gestations.

3. How do I counsel patients about the risk of prematurity?

The risk of spontaneous PTB varies with the gestational age that the short cervix is detected and with the degree of cervical shortening. The earlier in the pregnancy the cervix is found to be short, the higher the risk for spontaneous PTB. For example, results of one large multicenter study of almost 3,000 unselected women pregnant with a singleton gestation across the United States showed that a cervical length of 25 mm was associated with a 15% to 20% incidence of PTB when detected at 28 weeks’ gestation; the incidence rose to 30% to 35% if the short cervix was detected at 20 weeks.9 In this cohort, 84% of women had no history of PTB.

A short cervix and a prior PTB (particularly a very early prior PTB) are two major risk factors for PTB. Together, they significantly increase the risk of an early delivery over individual or single factors alone. Among women who have had a prior PTB and who now have a cervical length of less than 25 mm, the risk of recurrent PTB is 35% to 40%. In contrast, women with a prior PTB and a normal cervical length have a significantly lower risk of recurrence—around 10%.15

If the physical examination is concerning for cervical dilation or prolapsing membranes, women should be counseled about the poor prognosis for the pregnancy, particularly when these findings are detected at a previable or periviable gestational age, regardless of their history of PTB. In these circumstances, in the absence of labor or intra-amniotic infection, a “rescue” cervical cerclage may be considered as a last resort (see page 34 for more on cerclage).

4. What evaluation or monitoring is needed once a short cervix is identified?

Women found to have a short cervix should be evaluated for the presence of preterm labor and intra-amniotic infection. This evaluation may include a sterile speculum examination or digital cervical examination, or both, as well as screening for genitourinary tract infection. Other testing may include a complete blood count with a white blood cell differential and external tocometry with or without fetal heart rate monitoring (based on the gestational age, as appropriate).

For some women with a short cervix, intra-amniotic infection may be a contributing factor (or it may develop if there are exposed membranes in the vagina). The presence of intra-amniotic infection precludes further expectant management of the pregnancy because of the risk of maternal infectious morbidity, including sepsis.

Women who have intra-amniotic infection are not candidates for any intervention such as cerclage or progesterone supplementation.

If the patient is at or beyond the point of fetal viability at the time her short cervix is detected, consider external fetal heart rate monitoring.

Antenatal corticosteroids can be administered, as appropriate, depending on the perceived risk of delivery.

5. Should I place a cerclage?

Numerous studies have examined the efficacy of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, a surgical procedure to stitch the cervix closed once a short cervix has been detected.

In general, placement of a cervical cerclage is not offered past the point of fetal viability, which is generally in the range of 23 to 25 weeks’ gestation, depending on local institutional and neonatal intensive care unit policies. Confirmed or suspected chorioamnionitis is also a contraindication to cerclage placement.

Among women without a history of PTB who are found to have a short cervix, existing data do not suggest a benefit for cerclage, although vaginal progesterone appears to be a reasonable option (see page 36).16,17

As for women with a history of PTB, Owen and colleagues studied 302 patients with a cervical length less than 25 mm and a history of spontaneous PTB before 34 weeks.18 The women were randomly assigned to ultrasound-indicated cerclage or “usual care,” which consisted of recommendations of pelvic rest, physical activity restriction, and education about the symptoms of preterm labor. Otherwise, management was directed by clinical practice at each center. All women treated with cerclage had a reduced risk of previable PTB (<24 weeks’ gestation), and those who had the shortest cervical length (<15 mm) also had a lower risk of delivery before 35 weeks.