AMSTERDAM – Daily losartan significantly slowed the aortic root dilatation rate in adults with Marfan syndrome in a 3-year randomized clinical trial.

"I think we can be positive about this treatment. We can now recommend losartan in clinical practice," Dr. Maarten Groenink said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

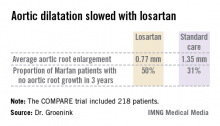

The COMPARE (Cozaar in Marfan Patients Reduces Aortic Enlargement) trial included 218 patients at all four university Marfan centers in the Netherlands. Patients were randomized to oral losartan at a target dose of 100 mg/day or no losartan in addition to standard-of-care treatment with beta-blockers. Roughly half of the patients in the losartan group were unable to tolerate the full dose of losartan in addition to a beta-blocker; those patients were maintained on losartan at 50 mg/day. Aortic root diameter was measured by MRI at enrollment and after 3 years of prospective follow-up. The aortic dilatation rate was significantly lower in the losartan group than in controls both in the patients with a native root and in those who had undergone aortic root replacement surgery, reported Dr. Groenink, a cardiologist at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

There were no aortic dissections in the losartan group and two in the control arm. Elective aortic replacement surgery was performed in a similar number of patients in both groups.

Blood pressure was lower in the losartan group, yet blood pressure didn’t correlate with the aortic dilatation rate. Dr. Groenink speculated that losartan’s chief mechanism of benefit in Marfan syndrome is its ability to curb overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta, which weakens the structure of the media layer of the aortic wall.

Dr. Groenink said it’s unknown whether losartan’s benefits are specific to that drug or are a class effect obtainable with other angiotensin II receptor antagonists, though he suspects it’s a class effect.

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating losartan in children and adolescents with Marfan syndrome, he said, adding that there is a solid rationale for beginning treatment as early in life as possible.

"I believe the adverse effects on the aortic wall in Marfan syndrome are caused by the fibrillin defect but also by wear and tear due to cyclic stress by the beating heart. So you can hypothesize that the earlier you start treatment, the better the results," he explained.

Marfan syndrome is a genetic connective tissue disorder affecting multiple organ systems. The prognosis is mainly determined by the aortic complications, including dilatation, aneurysm formation, and possible acute dissection. Affected individuals tend to be tall, long-limbed, and have distinctively long, thin fingers. The prevalence of Marfan syndrome has been estimated at 1 in 5,000, but Dr. Groenink suspects the syndrome may actually be more common than that.

Simultaneous with Dr. Groenink’s presentation at the ESC, the COMPARE results were published online (Eur. Heart J. 2013 [doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht334]).

The COMPARE trial was funded by the Dutch Heart Association. Dr. Groenink reported having no relevant financial interests.

*CORRECTION 11/14/13: The first version of this story had Dr. Groenink's name misspelled.