CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

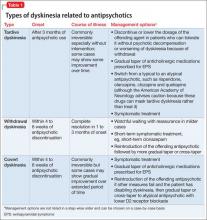

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.