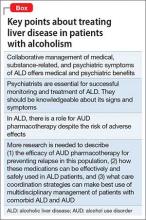

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mosaic of psychiatric and medical symptoms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in its acute and chronic forms is a common clinical consequence of long-standing AUD. Patients with ALD require specialized care from professionals in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. However, medical specialists treating ALD might not regularly consider medications to treat AUD because of their limited experience with the drugs or the lack of studies in patients with significant liver disease.1 Similarly, psychiatrists might be reticent to prescribe medications for AUD, fearing that liver disease will be made worse or that they will cause other medical complications. As a result, patients with ALD might not receive care that could help treat their AUD (Box).

Given the high worldwide prevalence and morbidity of ALD,2 general and subspecialized psychiatrists routinely evaluate patients with AUD in and out of the hospital. This article aims to equip a psychiatrist with:

• a practical understanding of the natural history and categorization of ALD

• basic skills to detect symptoms of ALD

• preparation to collaborate with medical colleagues in multidisciplinary management of co-occurring AUD and ALD

• a summary of the pharmacotherapeutics of AUD, with emphasis on patients with clinically apparent ALD.

Categorization and clinical features

Alcoholic liver damage encompasses a spectrum of disorders, including alcoholic fatty liver, acute alcohol hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis following varying durations and patterns of alcohol use. Manifestations of ALD vary from asymptomatic fatty liver with minimal liver enzyme elevation to severe acute AH with jaundice, coagulopathy, and high short-term mortality (Table 1). Symptoms seen in patients with AH include fever, abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, leukocytosis, and coagulopathy.3

Patients with chronic ALD often develop cirrhosis, persistent elevation of the serum aminotransferase level (even after prolonged alcohol abstinence), signs of portal hypertension (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), and profound malnutrition. The survival of ALD patients with chronic liver failure is predicted in part by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that incorporates their serum total bilirubin level, creatinine level, and international normalized ratio. The MELD score, which ranges from 6 to 40, also is used to gauge the need for liver transplantation; most patients who have a MELD score >15 benefit from transplant. To definitively determine the severity of ALD, a liver biopsy is required but usually is not performed in clinical practice.

All patients who drink heavily or suffer with AUD are at risk of developing AH; women and binge drinkers are particularly vulnerable.4 Liver dysfunction and malnutrition in ALD patients compromise the immune system, increasing the risk of infection. Patients hospitalized with AH have a 10% to 30% risk of inpatient mortality; their 1- and 2-month post-discharge survival is 50% to 65%, largely determined by whether the patient can maintain sobriety.5 Psychiatrists’ contribution to ALD treatment therefore has the potential to save lives.

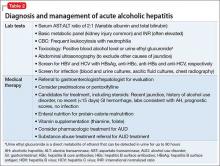

Screening and detection of ALD

Because of the high mortality associated with AH and cirrhosis, symptom recognition and collaborative medical and psychiatric management are critical (Table 2). A psychiatrist evaluating a jaundiced patient who continues to drink should arrange urgent medical evaluation. While gathering a history, mental health providers might hear a patient refer to symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding (vomiting blood, bloody or dark stool), painful abdominal distension, fevers, or confusion that should prompt a referral to a gastroenterologist or the emergency department. Testing for urinary ethyl glucuronide—a direct metabolite of ethanol that can be detected for as long as 90 hours after ethanol ingestion—is useful in detecting alcohol use in the past 4 or 5 days.

Medical management of ALD

Corticosteroids are a mainstay in pharmacotherapy for severe AH. There is evidence for improved outcomes in patients with severe AH treated with prednisolone for 4 to 6 weeks.5 Prognostic models such as the Maddrey’s Discriminant Function, Lille Model, and the MELD score help determine the need for steroid use and identify high-risk patients. Patients with active infection or bleeding are not a candidate for steroid treatment. An experienced gastroenterologist or hepatologist should initiate medical intervention after thorough evaluation.

Liver transplantation. A select group of patients with refractory liver failure are considered for liver transplantation. Although transplant programs differ in their criteria for organ listing, many require patients to demonstrate at least 6 months of verified abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs as well as adherence to a formal AUD treatment and rehabilitation plan. The patient’s psychological health and prognosis for sustained sobriety are central to candidacy for organ listing, which highlights the key role of psychiatrists.

Further considerations. Thiamine and folate often are given to patients with ALD. Abdominal imaging and screening for HIV and viral hepatitis—identified in 10% to 20% of ALD patients—is routine. Alcohol abstinence remains central to survival because relapse increases the risk of recurrent, severe liver disease. Regrettably, many physical symptoms of liver disease, such as portal hypertension, ascites, and jaundice, can take months to improve with abstinence.