Treating AUD in patients with ALD

Successful treatment is multifaceted and includes more than just medications. Initial management often includes addressing alcohol withdrawal in dependent patients.6

Behavioral interventions are effective and indispensable components in preventing relapse,7 including a written relapse prevention plan that formally outlines the patient’s commitment to change, identifies triggers, and outlines a discrete plan of action. Primary psychiatric pathology, including depression and anxiety, often are comorbid with AUD; concurrent treatment of these disorders could improve patient outcomes.8

Benzodiazepines often are used during acute alcohol withdrawal. They should not be used for relapse prevention in ALD because of their additive interactions with alcohol, cognitive and psychomotor side effects, and abuse potential.9,10 Many of these drugs are cleared by the liver and generally are not recommended for use in patients with ALD.

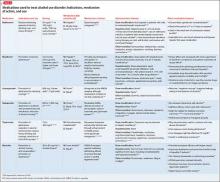

Other agents, further considerations. Drug trials in AUD largely have been conducted in small, heterogeneous populations and revealed modest and, at times, conflicting drug effect sizes.6,11,12 The placebo effect among the AUD population is pronounced.6,7,13 Despite these caveats, several agents have been studied and validated by the FDA to treat AUD. Additional agents with promising pilot data are being investigated. Table 31,7,10,11,13-43 summarizes drugs used to treat AUD—those with and without FDA approval—with a focus on how they might be used in patients with ALD. Of note, several of these agents do not rely on the liver for metabolism or excretion.

There is no agreed-upon algorithm or safety profile to guide a prescriber’s decision making about drug or dosage choices when treating AUD in patients with ALD. Because liver function can vary among patients as well as during an individual patient’s disease course, treatment decisions should be made on a clinical, collaborative, and case-by-case basis.

That being said, the AUD treatment literature suggests that specific drugs might be more useful in patients with varying severity of disease and during different phases of recovery:

• Acamprosate has been found to be effective in supporting abstinence in sober patients.14,44

• Naltrexone has been shown to be useful in patients with severe alcohol cravings. By modulating alcohol’s rewarding effects, naltrexone also reduces heavy alcohol consumption in patients who are drinking.14,15,44

• Disulfiram generally is not recommended for use in patients with clinically apparent hepatic insufficiency, such as decompensated cirrhosis or preexisting jaundice.

Although alcohol abstinence remains the treatment goal and a requirement for liver transplant, providers must recognize that some patients might not be able to maintain long-term sobriety. Therefore, harm reduction models are important companions to abstinence-only models of AUD treatment.45 The array of behavioral, pharmacological, and philosophical approaches to AUD treatment underlines the need for an individualized approach to relapse prevention.

Collaboration between medicine and psychiatry

When AUD and ALD are comorbid, psychiatrists might worry about making the patient’s medical condition worse by prescribing additional psychoactive medications—particularly ones that are cleared by the liver. Remember that AUD confers a substantial mortality rate that is more than 3 times that of the general population, along with severe medical46 and psychosocial31 effects. Although prescribers must remain vigilant for adverse drug effects, medications easily can be blamed for what might be the natural progression and symptoms of AUD in patients with ALD.26 This erroneous conclusion can lead to premature medication discontinuation and under-treatment of AUD.

In the end, keeping the patient sober and mentally well might be more beneficial than eliminating the burden of any medication side effects. Collaborative medical and psychiatric management of ALD patients can ensure that clinicians properly weigh the risks, benefits, and duration of treatment unique to each patient.

Starting AUD treatment promptly after alcohol relapse is essential and entails a multidisciplinary effort between medicine and psychiatry, both in and out of the hospital. Because the relapsing, ill ALD patient most often will be admitted to a medical specialist, AUD might not receive enough attention during the medical admission. Psychiatrists can help in initiating AUD treatment in the acute medical setting, which has been shown to improve the outpatient course.6 For medically stable ALD patients admitted for inpatient psychiatric care or presenting a clinic, the mental health clinician should be aware of key laboratory and physical exam findings.

Bottom Line

Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) require collaborative care from specialists in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. Psychiatrists have a role in identifying signs of ALD, prescribing medication to treat alcohol use disorder, and encouraging abstinence. There is some evidence supporting specific medications for varying severity of disease and different phases of recovery. Pharmacotherapy decisions should be made case by case.