Managing residual symptoms in schizophrenia

Few studies are devoted to pharmacological treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, likely because pharmacotherapy for older patients with schizophrenia can be challenging. Evidence-based treatment is based primarily on findings from younger patients who survived into later life. Clinicians often use the adage of geriatric psychiatry, “start low, go slow,” because older patients are susceptible to adverse effects associated with psychiatric medications, including cardiovascular, metabolic, anticholinergic, and extrapyramidal effects, orthostasis, sedation, falls, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Older patients with schizophrenia are at an increased risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and anticholinergic adverse effects, perhaps because of degeneration of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons.4 Lowering the anticholinergic load by discontinuing or reducing the dosage of medications with anticholinergic properties, when possible, is a key principle when treating these patients. This tactic could help improve cognition and quality of life by decreasing the risk of other anticholinergic adverse effects, including delirium, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Patients treated with typical antipsychotics are nearly twice as likely to develop tardive dyskinesia compared with those receiving atypical antipsychotics.5 Sedation, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects can cause cognitive clouding, worsen cognitive impairment, and increase the risk of falls, especially in older patients.6 Clozapine and olanzapine have the strongest association with clinically significant weight gain and treatment-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus.7

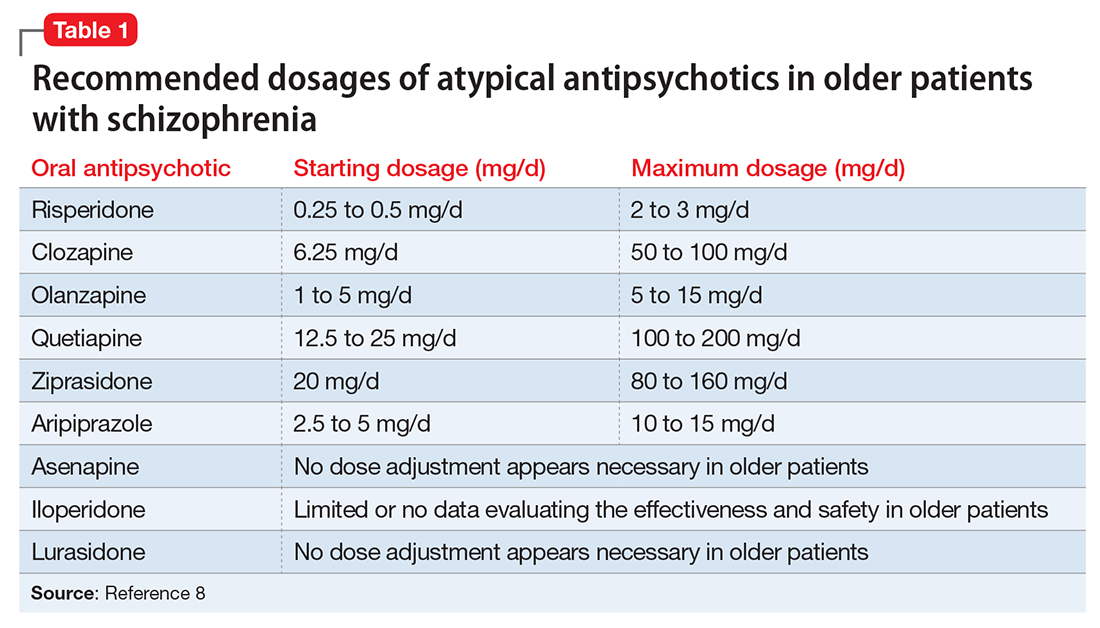

The appropriate starting dosage of antipsychotics in older patients with schizophrenia is one-fourth of the starting adult dosage. Total daily maintenance dosages may be one-third to one-half of the adult dosage.6 Consensus guidelines for dosing atypical antipsychotics for older patients with schizophrenia are as shown in Table 1.8

To ensure safety, patients should be regularly monitored with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, hemoglobin A1C, electrocardiogram, orthostatic vital signs, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and weight check.7,9

When negative symptoms remain after a patient has achieved remission, it is important to evaluate whether the symptoms are related to adverse effects of medication (eg, parkinsonism syndrome), untreated depressive symptoms, or persistent positive symptoms, such as paranoia. Management of these symptoms consists of treating the cause, for example, using antipsychotics for primary positive symptoms, antidepressants for depression, anxiolytics for anxiety, and anti-parkinsonian agents or antipsychotic dosage reduction for EPS.

It is important to differentiate between negative symptoms of schizophrenia and depression in these patients. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include affective flattening, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia. In depression, patients could have depressed mood, cognitive problems, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite. Also, long-term symptoms are more consistent with negative symptomatology.

Keep in mind the potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction when using a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine (to treat negative/depressive symptoms), because all are significant inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes and increase antipsychotic plasma level. The Expert Treatment Guidelines for Patients with Schizophrenia recommends SSRIs, followed by venlafaxine then bupropion to treat depressive symptoms after optimizing second-generation antipsychotics.9