CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

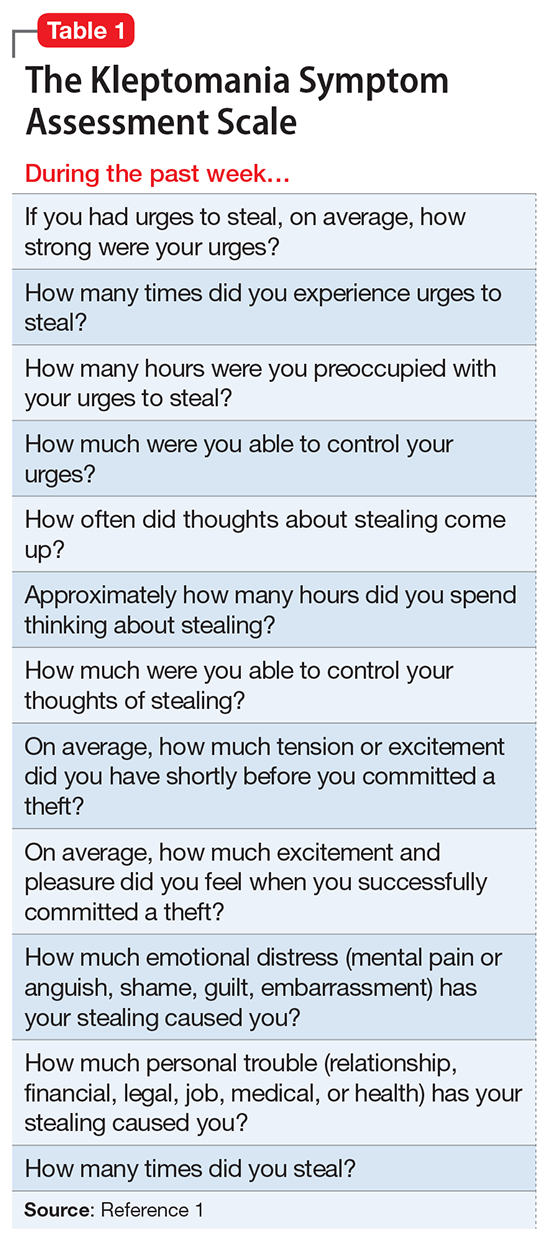

After 1 week in the partial hospitalization program, the psychiatrist asks Ms. B and her mother to complete the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale (K-SAS) (Table 1),1 which is designed to evaluate the severity of symptoms of kleptomania. Differential diagnoses of mania, antisocial personality disorder, uncontrolled ADHD, and ordinary stealing are considered. Although the scale is designed to be filled out only by the patient, Ms. B’s mother also was asked to fill it out to the best of her knowledge about her daughter’s symptoms to obtain a comparison of externalizing symptoms. The K-SAS score reveals that Ms. B has daily urges to steal and has been stealing every day. Further evaluation reveals that Ms. B meets DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 2).2