Our understanding of pain mechanisms continues to evolve and, accordingly, so do our treatment strategies. The fundamental differences between acute and chronic pain were only recently recognized; this lack of recognition led to the application of acute pain treatments to chronic pain, contributing to the opioid epidemic in the United States.

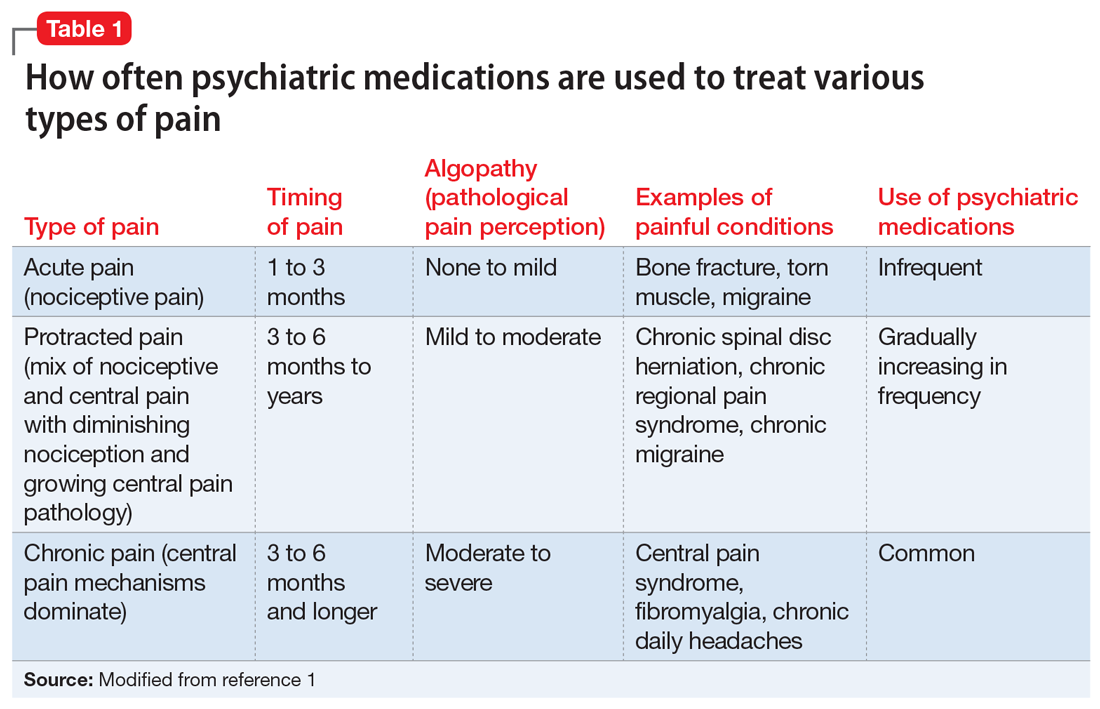

With the diminishing emphasis on opioid medications, researchers are exploring other pharmacologic modalities for treating pain. Many nonopioid psychiatric medications are used off-label for the treatment of pain. Psychiatric medications play a larger role in the management of pain as pain becomes more chronic (Table 11). For simplicity, acute pain may be seen as nociception colored by emotions, and chronic pain as emotions colored by nociception. Protracted pain connects those extremes with a diminishing role of nociception and an increasing role of emotion,1 which may increase the potential role of psychiatric medications, including antipsychotics.

In this article, I discuss the potential role of dopamine in the perception of pain, and review the potential use of first- and second-generation antipsychotics for treating various pain syndromes.

Role of dopamine in pain

There is increasing interest in exploring antipsychotics to treat chronic pain2 because dopamine dysfunction is part of pathological pain perception. Excess dopamine is associated with headaches (dopamine hypersensitivity hypothesis3,4) and dopamine dysfunction is a part of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),5 dissociation,6 paranoia,7 and catastrophizing.8 Somatic psychosis, like any psychosis, can be based on dopamine pathology. Dopaminergic neurons affect nociceptive function in the spinal dorsal horn,9 and dopamine receptors are altered in atypical facial pain,10 burning mouth syndrome,11 and fibromyalgia.12

In normal circumstances, dopamine is fundamentally a protective neurotransmitter. In acute pain, dopamine is powerfully released, making the pain bearable. A patient may describe acute pain as seeming “like it was not happening to me” or “it was like a dream”; both are examples of dopamine-caused dissociation and a possible prediction of subsequent chronification. In chronic pain, pathological mechanisms settle in and take root; therefore, keeping protective dopamine levels high becomes a priority. This is especially common in patients who have experienced abuse or PTSD. The only natural way to keep dopamine up for prolonged periods of time is to decrease pain and stress thresholds. Both phenomena are readily observed in patients with pain. In extreme cases, self-mutilation and involvement in conflicts become pathologically gratifying.

The dopaminergic system is essential for pain control with a tissue injury.13 It becomes pathologically stimulated and increasingly dysfunctional as algopathy (a pathological pain perception) develops. At the same time, a flood or drought of any neurotransmitter is equally bad and may produce similar clinical pictures. Both a lack of and excess of dopamine are associated with pain.14 This is why opposite treatments may be beneficial in different patients with chronic pain. As an example, the use of stimulants15 and bupropion16 has been reported in the treatment of abdominal pain. And, reversely, antipsychotics, especially first-generation agents, may be associated with chronic (tardive) pain, including orofacial and genital pain.17

First-generation antipsychotics

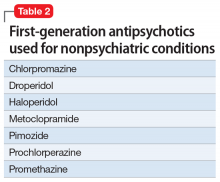

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) have been used to treat various nonpsychiatric conditions (Table 2). Although they are powerful D2 receptor inhibitors, FGAs lack the intrinsic ability to counteract the unwanted adverse effects of strong inhibition. As a result, movement disorders and prolactinemia are commonly induced by FGAs. The most dangerous consequence of treatment with these agents is neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS).

Continue to: Haloperidol