Ms. T, age 48, is brought to the psychiatric emergency department after the police find her walking along the highway at 3:00 am. Ms. T paces back and forth, gesticulating while she tries to explain her concerns related to an alien invasion, contaminated drinking water, and “FBI microchipping.” Urine and serum toxicology studies are negative. On the unit, she is seclusive and mumbles nonsensical statements about having to “take out the leader of the opposition.” Ms. T consistently refuses recommended medications (antipsychotics) because she believes the treatment team is trying to poison her. She is subsequently civilly committed to the inpatient psychiatric facility.

Once involuntarily committed, does Ms. T have the right to refuse treatment?

Every psychiatrist has faced the predicament of a patient who refuses treatment. This creates an ethical dilemma between respecting the patient’s autonomy vs forcing treatment to ameliorate symptoms and reduce suffering. This article addresses case law related to the models for administering psychiatric medications over objection. We also discuss case law regarding court-appointed guardianship, and treating medical issues without consent. While this article provides valuable information on these scenarios, it is crucial to remember that the legal processes required to administer medications over patient objection are state-specific. In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, you must research the legal procedures specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

History of involuntary treatment

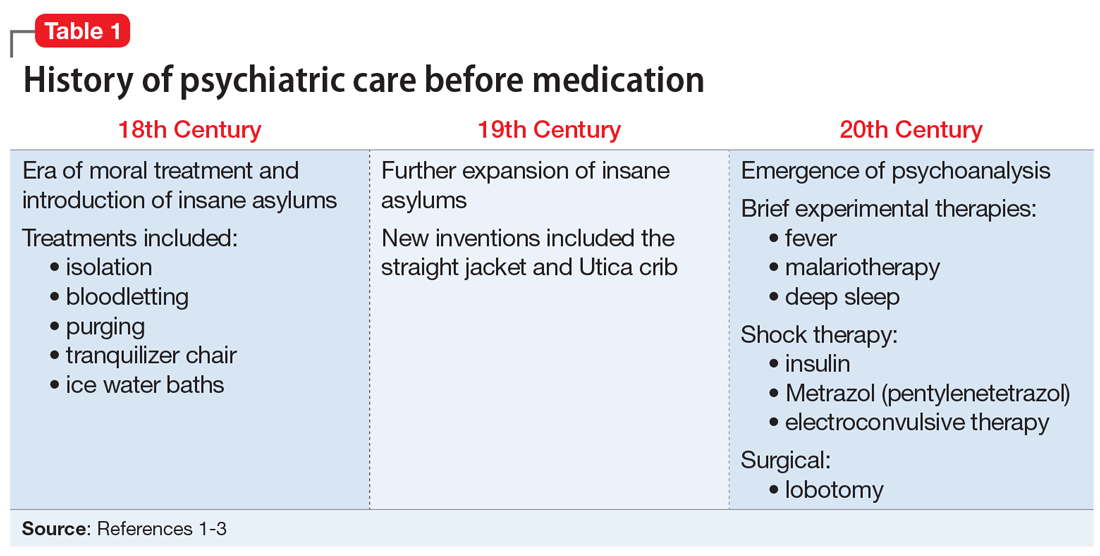

Prior to the 1960s, Ms. T would likely have been unable to refuse treatment. All patients were considered involuntary, and the course of treatment was decided solely by the psychiatric institution. Well into the 20th century, patients with psychiatric illness remained feared and stigmatized, which led to potent and potentially harsh methods of treatment. Some patients experienced extreme isolation, whipping, bloodletting, experimental use of chemicals, and starvation (Table 11-3).

With the advent of psychotropic medications and a focus on civil liberties, the psychiatric mindset began to change from hospital-based treatment to a community-based approach. The value of psychotherapy was recognized, and by the 1960s, the establishment of community mental health centers was gaining momentum.

In the context of these changes, the civil rights movement pressed for stronger legislation regarding autonomy and the quality of treatment available to patients with psychiatric illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rouse v Cameron4 and Wyatt v Stickney5 dealt with a patient’s right to receive treatment while involuntarily committed. However, it was not until the 1980s that the courts addressed the issue of a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

The judicial system: A primer

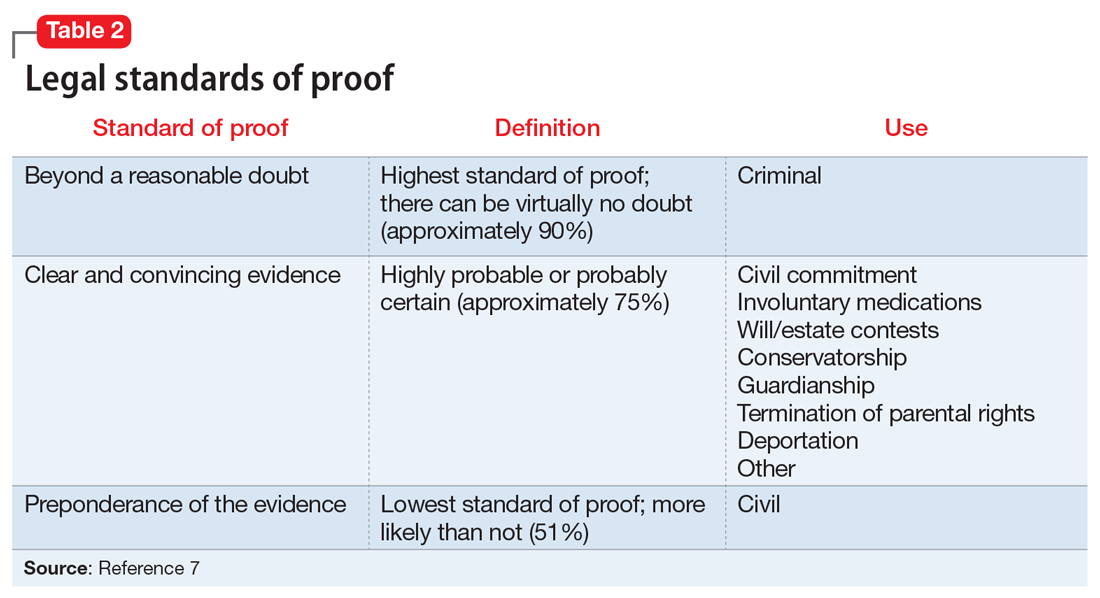

When reviewing case law and its applicability to your patients, it is important to understand the various court systems. The judicial system is divided into state and federal courts, which are subdivided into trial, appellate, and supreme courts. When decisions at either the state or federal level require an ultimate decision maker, the US Supreme Court can choose to hear the case, or grant certiorari, and make a ruling, which is then binding law.6 Decisions made by any court are based on various degrees of stringency, called standards of proof (Table 27).

Continue to: For Ms. T's case...