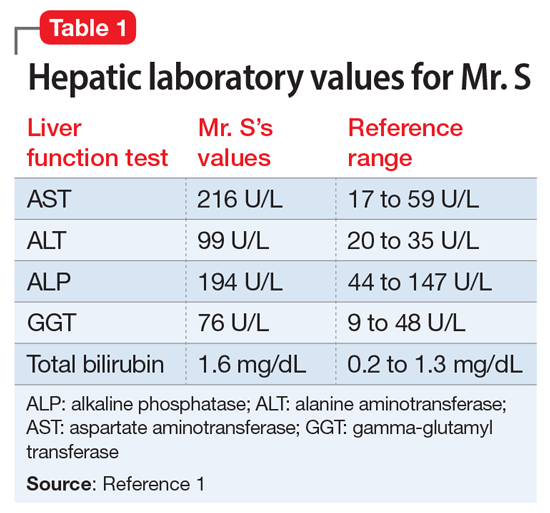

Mr. S, age 64, presents for an outpatient follow-up after a recent hospital discharge for alcohol detoxification. He reports a long history of alcohol use, which has resulted in numerous hospital admissions. He has recently been receiving care from a gastroenterologist because the results of laboratory testing suggested hepatic impairment (Table 1). Mr. S says that a friend of his was able to stop drinking by taking a medication, and he wonders if he can be prescribed a medication to help him as well.

A chart review shows that Mr. S recently underwent paracentesis, during which 6 liters of fluid were removed. Additionally, an abdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic cirrhosis.

According to the World Health Organization, alcohol consumption contributes to 3 million deaths annually.2 The highest proportion of these deaths (21.3%) is due to alcohol-associated gastrointestinal complications, including alcoholic and infectious hepatitis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Because the liver is the primary site of ethanol metabolism, it sustains the greatest degree of tissue injury with heavy alcohol consumption. Additionally, the association of harmful use of alcohol with risky sexual behavior may partially explain the higher prevalence of viral hepatitis among persons with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared with the general population. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) progresses through several stages, beginning with hepatic steatosis and progressing through alcohol-related hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and potentially hepatocellular carcinoma.3

Liver markers of alcohol use

Although biological markers can be used in clinical practice to screen and monitor for alcohol abuse, making a diagnosis of ALD can be challenging. Typically, a history of heavy alcohol consumption in addition to certain physical signs and laboratory tests for liver disease are the best indicators of ALD. However, the clinical assessment can be confounded by patients who deny or minimize how much alcohol they have consumed. Furthermore, physical and laboratory findings may not be specific to ALD.

Liver enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), have historically been used as the basis of diagnosing ALD. In addition to elevated bilirubin and evidence of macrocytic anemia, elevations in these enzymes may suggest heavy alcohol use, but these values alone are inadequate to establish ALD. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is found in cell membranes of several body tissues, including the liver and spleen, and therefore is not specific to liver damage. However, elevated GGT is the best indicator of excessive alcohol consumption because it has greater sensitivity than AST and ALT.1,3,4

Although these biomarkers are helpful in diagnosing ALD, they lose some of their utility in patients with advanced liver disease. Patients with severe liver dysfunction may not have elevated serum aminotransferase levels because the degree of liver enzyme elevation does not correlate well with the severity of ALD. For example, patients with advanced cirrhosis may have liver enzyme levels that appear normal. However, the pattern of elevation in transaminases can be helpful in making a diagnosis of liver dysfunction; using the ratio of AST to ALT may aid in diagnosing ALD, because AST is elevated more than twice that of ALT in >80% of patients with ALD.1,3,4

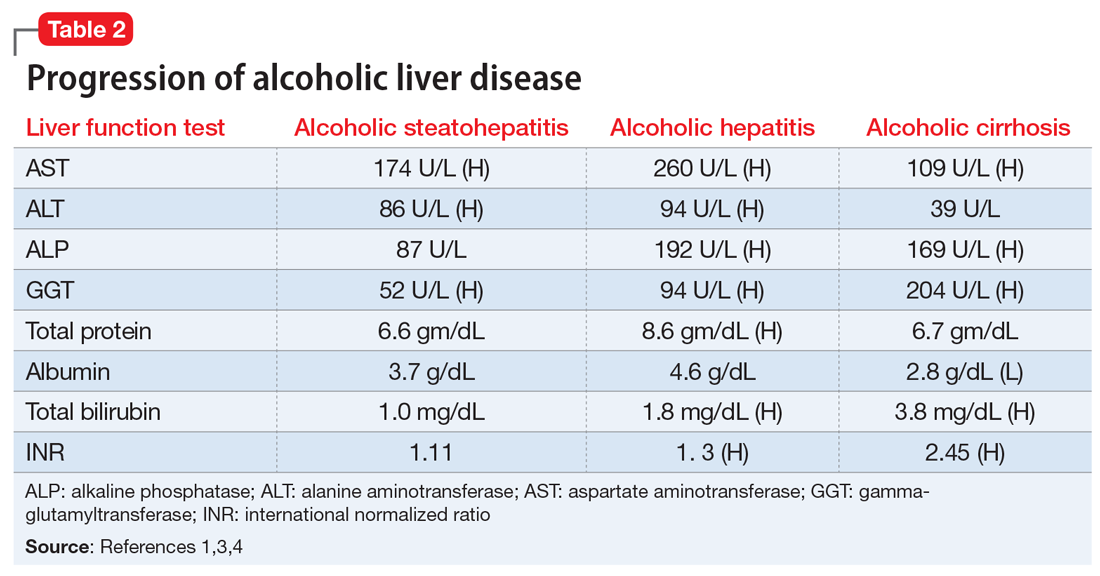

Table 21,3,4 shows the progression of ALD from steatohepatitis to alcoholic hepatitis to cirrhosis. In steatohepatitis, transaminitis is present but all other biomarkers normal. In alcoholic hepatitis, transaminitis is present along with elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated bilirubin, and elevated international normalized ratio (INR). In alcoholic cirrhosis, the AST-to-ALT ratio is >2, and hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy (evidenced by elevated INR) are present, consistent with long-term liver damage.1,3,4

Continue to: FDA-approved medications