Abrupt cessation or reduction of alcohol consumption may result in alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), which is a medical emergency that can lead to serious complications when unrecognized or treatment is delayed. Symptoms of AWS include tremors, anxiety attacks, cognitive impairment, hallucinations, seizures, delirium tremens (DT), and in severe, untreated cases, death.1 Low to moderate alcohol consumption produces euphoria and excitation via activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission, while higher concentrations produce severe intoxication via GABAergic mechanisms. Acute withdrawal unmasks the hyper-excitatory state of the brain, causing anxiety, agitation, and autonomic activation characteristic of AWS, which typically begins 1 to 3 days after the last drink.2 In the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the 12-month and lifetime prevalences of AWS were 13.9% and 29.1%, respectively.3 Within the general inpatient population, AWS can be present in nearly 30% of patients; if left untreated, AWS has a 15% mortality rate, although when AWS is recognized early and treated, the mortality rate falls dramatically to 2%.4

AWS has most commonly been treated with benzodiazepines.5 However, benzodiazepines have the potential for significant adverse effects when used in older adults and in individuals with complicated medical issues, such as obstructive lung disease and sleep apnea.6 Anticonvulsants have been increasingly used to treat alcohol withdrawal, and their use is supported by several retrospective and prospective studies. In this article, we review the data from randomized control trials (RCTs) on the use of anticonvulsants for the treatment of AWS to see if we can make any recommendations for the use of anticonvulsants for treating AWS.

Our literature search

We searched 5 databases (PubMed, Cochrane, Medline, PsycInfo, and Embase) using the following terms: “alcohol withdrawal syndrome treatment”, “anticonvulsants”, “anti-epileptic”, “gabapentin”, “carbamazepine”, “sodium valproate”, “oxcarbazepine”, “phenytoin”, “levetiracetam”, and “lamotrigine.” We included only double-blind RCTs published between January 1, 1976 and September 30, 2016 in English-language journals or that had an official English translation. There were no restrictions on patient age or location of treatment (inpatient vs outpatient). All RCTs that compared anticonvulsants or a combination of an anticonvulsant and an active pharmacotherapeutic agent with either placebo or gold standard treatment for AWS were included. Database reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded.

We identified 662 articles that met these criteria. However, most were duplicates, review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, or open-label or non-randomized trials. Only 16 articles met our inclusion criteria. In the following sections, we discuss these 16 studies by medication type and in chronological order.

Gabapentin

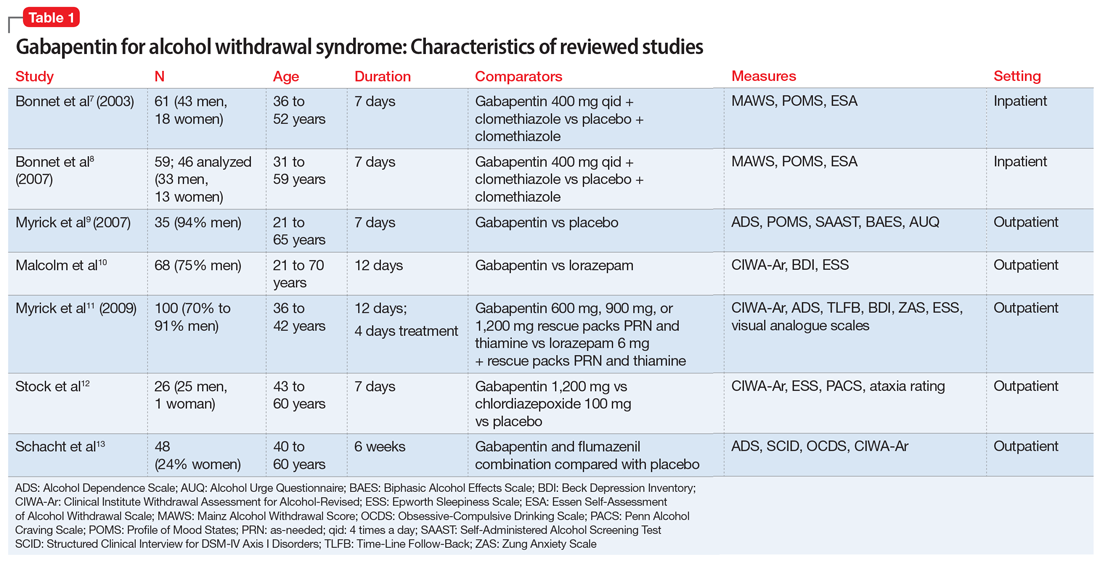

The characteristics of the gabapentin studies included in this review are summarized in Table 1.7-13

Bonnet et al7 (2003) examined 61 adults who met the clinical criteria for alcohol dependence and displayed moderate or severe AWS according to their Mainz Alcohol Withdrawal Score (MAWS ≥4). They were randomized to receive placebo or gabapentin, 400 mg 4 times a day, along with clomethiazole. The attrition rate was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .66). The difference in the number of clomethiazole capsules taken during the first 24 hours between the groups was small and not significant (P = .96). Analysis of MAWS over time revealed no significant main effect for group (P = .26) and a significant effect for the time variable (P < .001). The interaction between group and time was not significant (P =.4). This means that there was a significant decrease in MAWS from baseline over 48 hours, and this decrease in MAWS was considered equal for both study groups. Adverse clinical events were observed in both groups, and there was no significant difference (P = .74) between the groups. Nausea and ataxia, which are specific to gabapentin, were observed more frequently in this group.

Conclusion: The authors concluded that gabapentin, 400 mg 4 times a day, is no better than placebo in reducing the amount of clomethiazole required to treat acute AWS.7

Continue to: Bonnet et al