EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

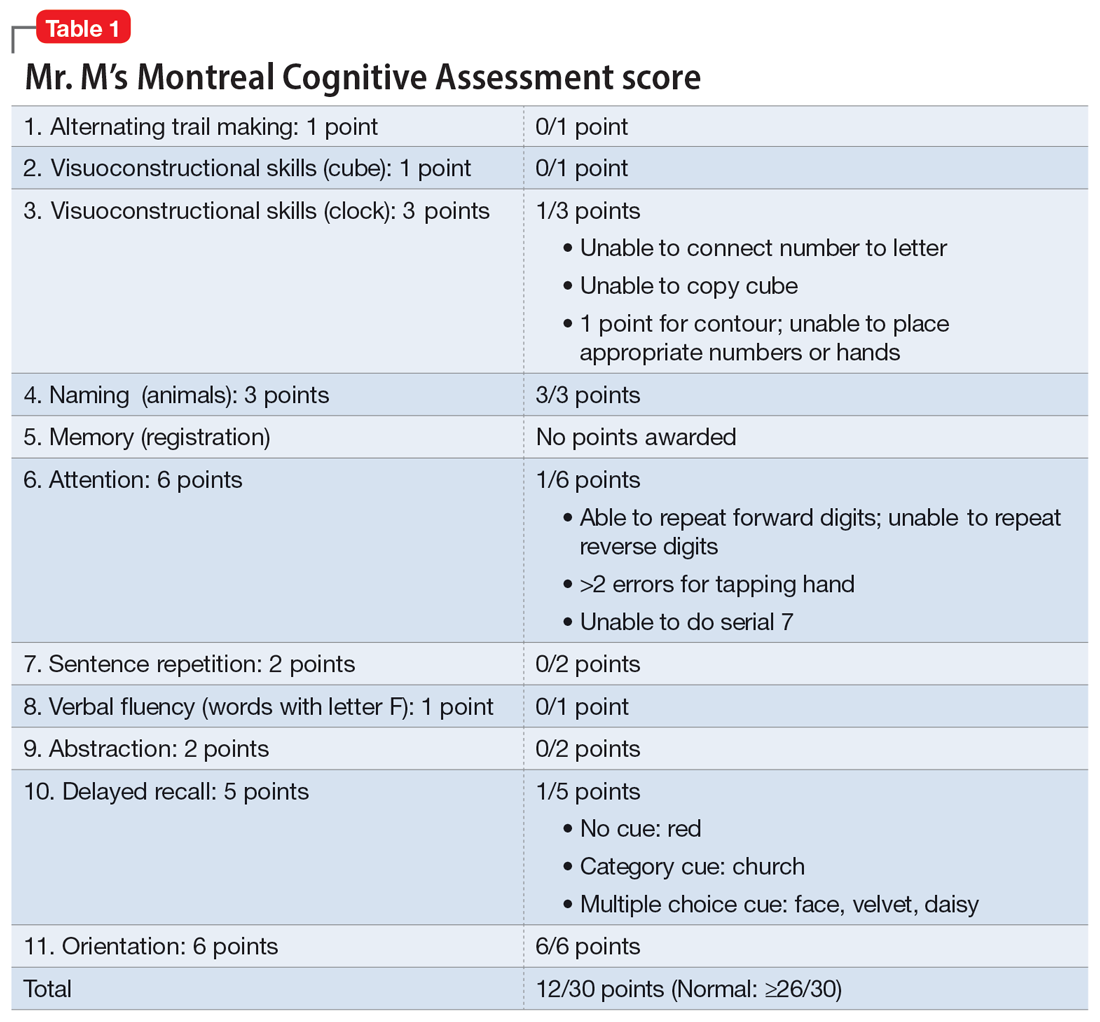

Mr. M scores 12/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating moderate cognitive impairment (Table 1). The psychiatrist refers Mr. M to Neurology. During his neurologic evaluation, Mr. M continues to report feeling anxious that “something is wrong” and skips his words. The neurologist confirms Mr. M’s symptoms may have started 2 to 3 months before he presented to the ED. Mr. M reports unusual eating habits, including yogurt and cookies for breakfast, Mexican food for lunch, and more cookies for dinner. He denies having a fever, gaining or losing weight, rashes, headaches, neck stiffness, tingling or weakness or stiffness of limbs, vertigo, visual changes, photophobia, unsteady gait, bowel or bladder incontinence, or tremors.

When the neurologist repeats the MoCA, Mr. M again scores 12. The neurologist notes that Mr. M answers questions a little slowly and pauses for thoughts when unable to find an answer. Mr. M has difficulty following some simple commands, such as “touch a finger to your nose.” Other in-office neurologic physical exams (cranial nerves, involuntary movements or tremors, sensation, muscle strength, reflexes, cerebellar signs) are unremarkable except for mildly decreased vibration sense of his toes. The neurologist concludes that Mr. M’s presentation is suggestive of subacute to chronic bradyphrenia and orders additional evaluation, including neuropsychological testing.

The authors’ observations

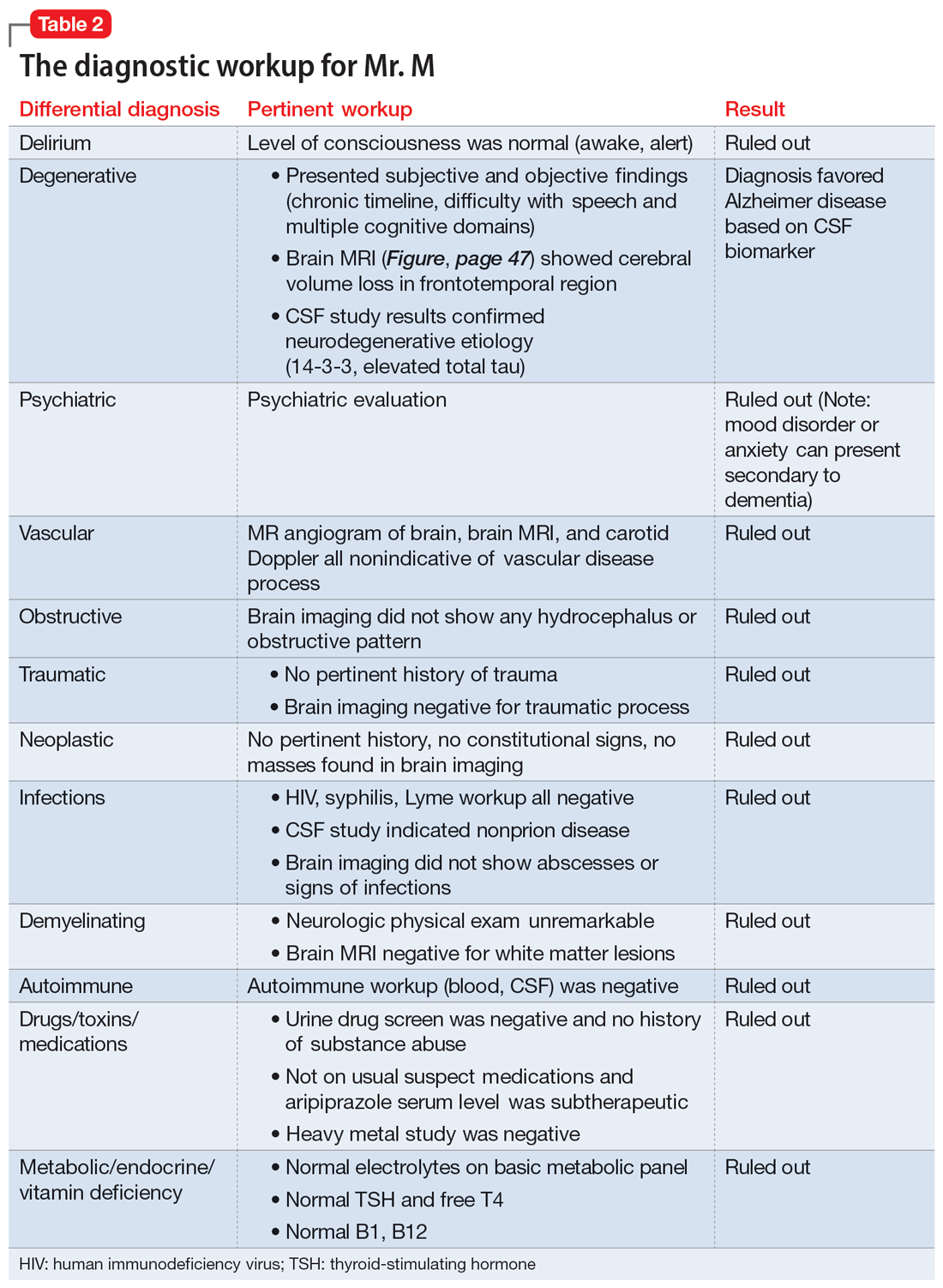

Physical and neurologic exams were not suggestive of any obvious causes of cognitive decline. Both the mental status exam and 2 serial MoCAs suggested deficits in executive function, language, and memory. Each of the differential diagnoses considered was ruled out with workup or exams (Table 2), which led to a most likely diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder with PPA. Neuropsychological testing confirmed the diagnosis of nonfluent PPA.

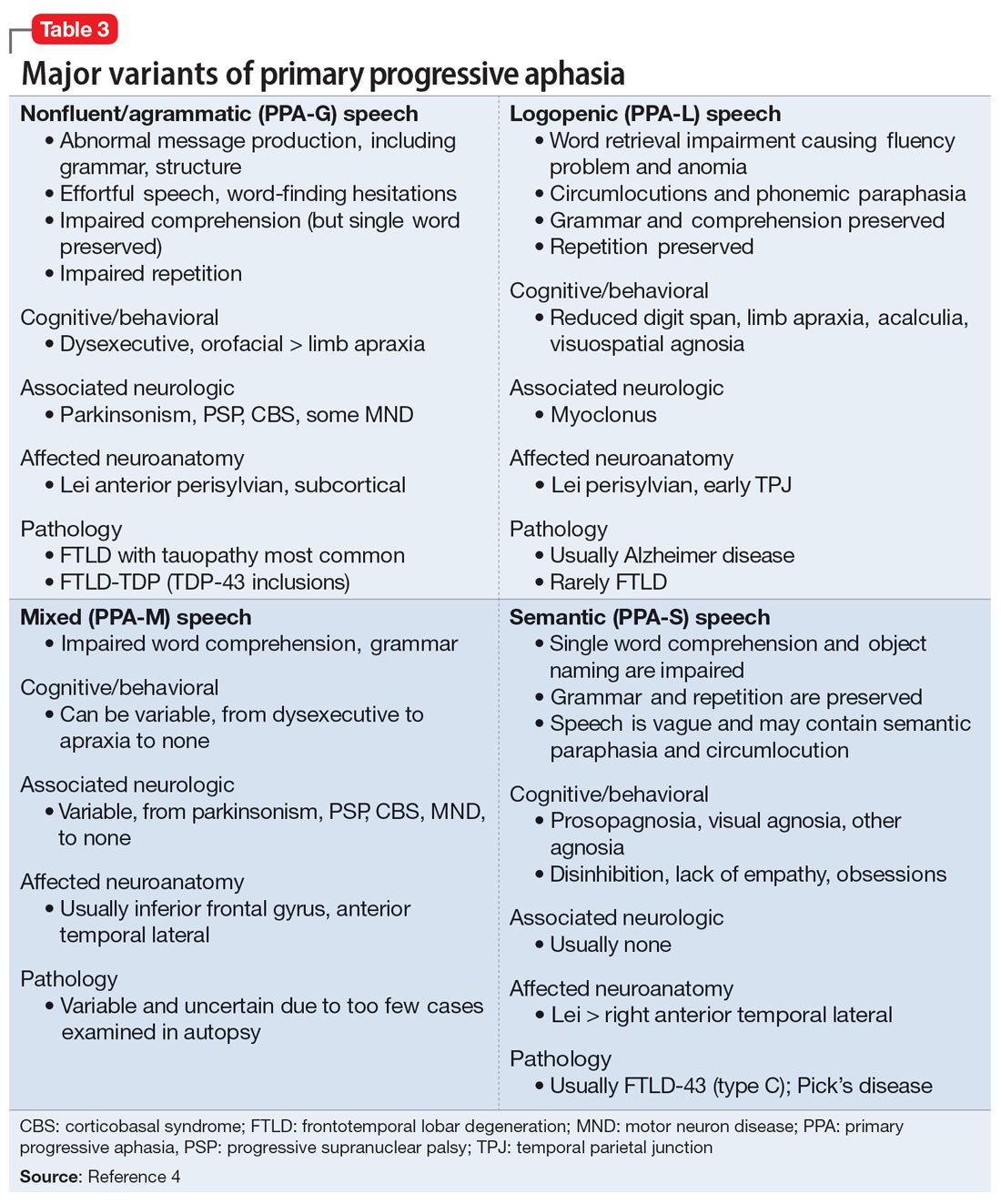

Primary progressive aphasia

PPA is an uncommon, heterogeneous group of disorders stemming from focal degeneration of language-governing centers of the brain.1,2 The estimated prevalence of PPA is 3 in 100,000 cases.2,3 There are 4 major variants of PPA (Table 34), and each presents with distinct language, cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neuropathological characteristics.4 PPA is usually diagnosed in late middle life; however, diagnosis is often delayed due to the relative obscurity of the disorder.4 In Mr. M’s case, it took approximately 4 months of evaluations by various specialists before a diagnosis was confirmed.

The initial phase of PPA can present as a diagnostic challenge because patients can have difficulty articulating their cognitive and language deficits. PPA can be commonly mistaken for a primary psychiatric disorder such as MDD or anxiety, which can further delay an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Special attention to the mental status exam, close observation of the patient’s language, and assessment of cognitive abilities using standardized screenings such as the MoCA or Mini-Mental State Examination can be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis. It is also important to rule out developmental problems (eg, dyslexia) and hearing difficulties, particularly in older patients.4

Continue to: TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen