CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

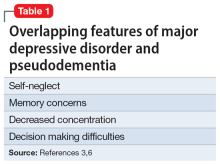

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6 Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression