CASE A relapse and crisis

Ms. G, age 32, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by police after being found in a stupor-like state in a public restroom. The consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry team assesses her for concerns of self-harm and suicide behavior. Ms. G discloses that she “huffs” an average of 4 canisters of air dusters daily to cope with psychosocial stressors and achieve a euphoric state. She recently lost her job, which led to homelessness, financial difficulties, a relapse to aerosol use after 2 years of abstinence, and stealing aerosol cans. The latest incident follows 2 prior arrests, which led officers to bring her to the ED for medical evaluation. Ms. G has a history of bipolar disorder (BD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), insomnia, and inhalant use disorder.

HISTORY Inhalant abuse and suicide attempt

Ms. G reports a longstanding history of severe inhalant abuse, primarily with air dusters due to their accessibility and low cost. She previously underwent inpatient rehab for inhalant abuse, and received inpatient psychiatry treatment 5 years ago for a suicide attempt by overdose linked to psychosocial stressors. In addition to BD, GAD, insomnia, and inhalant use disorder, Ms. G has a history of neuropathy, seizures, and recurrent hypokalemia. She is single and does not have insurance.

The authors’ observations

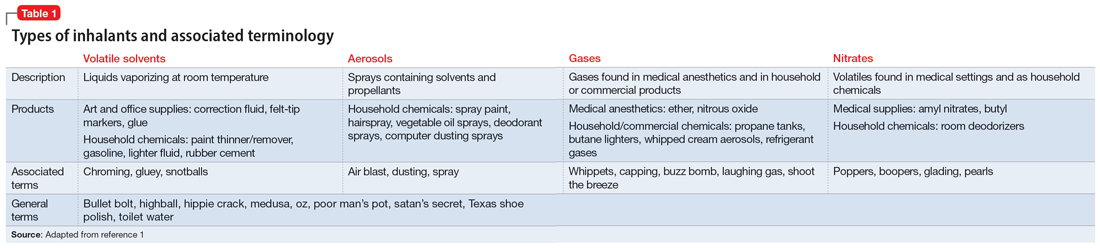

Inhalant abuse is the intentional inhalation of volatile substances to achieve an altered mental state. Inhalants are commercially available products that can produce intoxication if inhaled, such as glue, toluene, spray paint, gasoline, and lighter fluid (Table 11).

The epidemiology of inhalant abuse is difficult to accurately report due to a lack of recognition and social stigma. Due to inhalants’ ease of access and low cost, this form of substance abuse is popular among adolescents, adults of low socioeconomic status, individuals who live in rural areas, and those living in institutions. Inhalants act as reinforcers, producing a euphoric state. Rapid pulmonary absorption and lipid solubility of the substance rapidly alters the brain. Inhalant abuse can result in chemical and thermal burns, withdrawal symptoms, persistent mental illness, and catastrophic medical emergencies such as ventricular arrhythmias leading to disruptive myocardial electrical propagation. Chronic abuse can cause irreversible neurological and neuropsychological effects, cardiomyopathy, rapid airway compromise, pulmonary debilitations, renal tubular acidosis, bone marrow toxicity, reduced immunity, and peripheral neuropathy.2 Ms. G’s diagnosis of inhalant use disorder was based on her mental state and history of severe inhalant misuse, specifically with air dusters. Several additional factors further support this diagnosis, including the fact she survived a suicide attempt by overdose 5 years ago, had an inpatient rehabilitation placement for inhalant abuse, experiences insomnia, and was attempting to self-treat a depressive episode relapse with inhalants.

EVALUATION Depressed but cooperative

After being monitored in the ED for several hours, Ms. G is no longer in a stupor-like state. She has poor body habitus, appears older than her stated age, and is unkempt in appearance/attire. She is mildly distressed but relatively cooperative and engaged during the interview. Ms. G has a depressed mood and is anxious, with mood-congruent affect, and is tearful at times, especially when discussing recent stressors. She denies suicidality, homicidality, paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations. Her thought process is linear, goal-directed, and logical. She has fair insight, but relatively poor and impulsive judgment. The nursing staff expresses concerns that Ms. G was possibly responding to internal stimuli and behaving bizarrely during her initial presentation; this was not evident upon examination.

Ms. G reports having acute-on-chronic headaches, intermittent myalgias and weakness in her lower extremities (acute), and polyneuropathy (chronic). She denies a history of manic episodes or psychosis but reports previous relative hypomanic episodes that vacillated with periods of recurrent depressive episodes. Ms. G denies using illicit substances other than tobacco and inhalants. She says she had adhered to her outpatient psychiatric management services and medication regimen (duloxetine 60 mg/d at bedtime for mood/migraines, trazodone 150 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, ziprasidone 40 mg/d at bedtime for BD, carbamazepine 200 mg twice daily for neuropathy/migraines, gabapentin 400 mg 3 times daily for neuropathy migraines/anxiety, and propranolol 10 mg 3 times daily for anxiety/tremors/migraine prophylaxis) until 4 days before her current presentation to the ED, when she used inhalants and was arrested.

Ms. G’s vitals are mostly unremarkable, but her heart rate is 116 beats per minute. There are no acute findings on physical examination. She is not pregnant, and her creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, complete blood count, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are all within normal limits. Her blood sugar is high (120 mg/dL; reference range 70 to 100 mg/dL). She has slight transaminitis with high aspartate aminotransferase (93 U/L; reference range 17 to 59 U/L) and high alanine aminotransferase (69 U/L; reference range 20 to 35 U/L); chronic hypokalemia (2.4 mmol/L; reference range 3.5 to 5.2 mmol/L), which leads the primary team to initiate a potassium replacement protocol; lactic acidosis (2.2 mmol/L; normal levels <2 mmol/L); and creatine kinase (CK) 5,930 U/L.

Continue to: The authors' observations