Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is common, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5.29% among children and adolescents and 2.5% among adults.1 DSM-5-TR classifies ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, “a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period [that] typically manifest early in development, often before the child enters school.”2 Because of the expectation that ADHD symptoms emerge early in development, the diagnostic criteria specify that symptoms must have been present prior to age 12 to qualify as ADHD. However, recent years have shown a significant increase in the number of patients being diagnosed with ADHD for the first time in adulthood. One study found that the diagnosis of ADHD among adults in the United States doubled between 2007 and 2016.3

First-line treatment for ADHD is the stimulants methylphenidate and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. In the United States, these medications are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, indicating a high risk for abuse. However, just as ADHD diagnoses among adults have increased, so have prescriptions for stimulants. For example, Olfson et al4 found that stimulant prescriptions among young adults increased by a factor of 10 between 1994 and 2009.

The increased prevalence of adult patients diagnosed with ADHD and taking stimulants frequently places clinicians in a position to consider the validity of existing diagnoses and evaluate new patients with ADHD-related concerns. In this article, we review some of the challenges associated with diagnosing ADHD in adults, discuss the risks of stimulant treatment, and present a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults.

Challenges in diagnosis

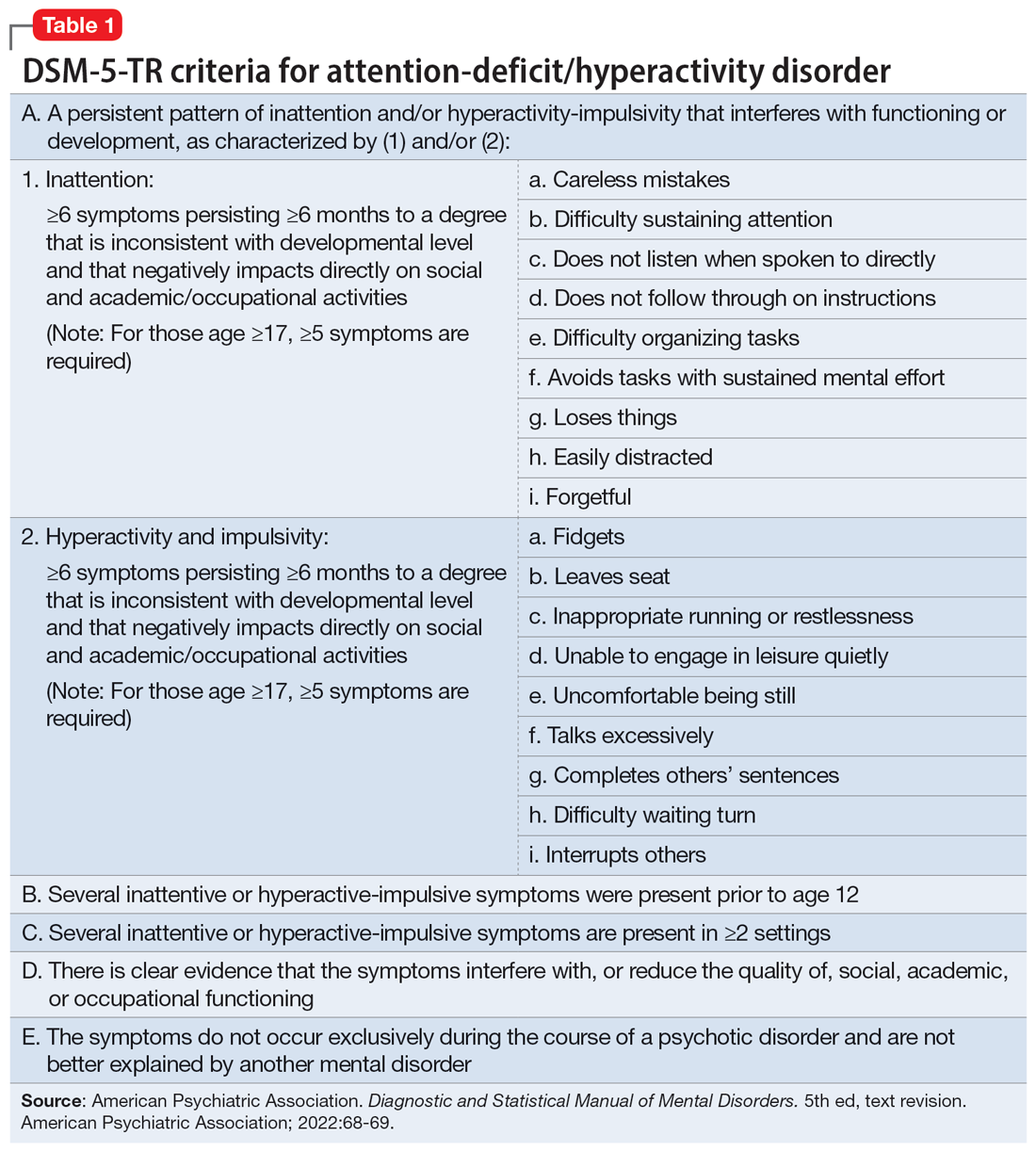

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD are summarized in Table 1. Establishing a diagnosis of adult ADHD can be challenging. As with many psychiatric conditions, symptoms of ADHD are highly subjective. Retrospectively diagnosing a developmental condition in adults is often biased by the patient’s current functioning.5 ADHD has a high heritability and adults may inquire about the diagnosis if their children are diagnosed with ADHD.6 Some experts have cautioned that clinicians must be careful in diagnosing ADHD in adults.7 Just as there are risks associated with underdiagnosing ADHD, there are risks associated with overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis may medicalize normal variants in the population and lead to unnecessary treatment and a misappropriation of limited medical resources.8 Many false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be attributable to nonimpairing cognitive fluctuations.9

Poor diagnostic practices can impede accuracy in establishing the presence or absence of ADHD. Unfortunately, methods of diagnosing adult ADHD have been shown to vary widely in terms of information sources, diagnostic instruments used, symptom threshold, and whether functional impairment is a requirement for diagnosis.10 A common practice in diagnosing adult ADHD involves asking patients to complete self-report questionnaires that list symptoms of ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale developed by the World Health Organization.11 However, self-reports of ADHD in adults are less reliable than informant reports, and some young adults without ADHD overreport symptoms.12,13 Symptom checklists are particularly susceptible to faking, which lessens their diagnostic value.14

The possibility of malingered symptoms of ADHD further increases the diagnostic difficulty. College students may be particularly susceptible to overreporting ADHD symptoms in order to obtain academic accommodations or stimulants in the hopes of improving school performance.15 One study found that 25% to 48% of college students self-referred for ADHD evaluations exaggerated their symptoms.16 In another study, 31% of adults failed the Word Memory Test, which suggests noncredible performance in their ADHD evaluation.17 College students can successfully feign ADHD symptoms in both self-reported symptoms and computer-based tests of attention.18 Harrison et al19 summarized many of these concerns in their 2007 study of ADHD malingering, noting the “almost perfect ability of the Faking group to choose items … that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms, and to report these at levels even higher than persons with diagnosed ADHD.” They suggested “Clinicians should be suspicious of students or young adults presenting for a first-time diagnosis who rate themselves as being significantly symptomatic, yet have managed to achieve well in school and other life activities.”19

Another challenge in correctly diagnosing adult ADHD is identifying other conditions that may impair attention.20 Psychiatric conditions that may impair concentration include anxiety disorders, chronic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, recent trauma, major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar disorder (BD). Undiagnosed learning disorders may present like ADHD. Focus can be negatively affected by sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, or delayed sleep phase-onset disorder. Marijuana, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA; “ecstasy”), caffeine, or prescription medications such as anticholinergics can also impair attention. Medical conditions that can present with attentional or executive functioning deficits include seizures, Lyme disease, HIV, encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, and “chemo brain.”21 Environmental factors such as age-related cognitive decline, sleep deprivation, inflammation, obesity, air pollution, chemical exposure, and excessive use of digital media may also produce symptoms similar to ADHD. Two studies of adult-onset ADHD concluded that 93% to 95% of cases were better explained by other conditions such as sleep disorders, substance use disorders, or another psychiatric disorder.22

Continue to: Risks associated with treatment