Ms. B, age 45, has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD) and migraines. She is admitted after presenting with anhedonia, hopelessness, and hypersomnia. These symptoms have become more severe over the last few weeks. Ms. B describes a past suicide attempt via overdose on doxylamine for which she required treatment in the intensive care unit. The only activity she enjoys is her weekly girls’ night, during which she drinks a few glasses of wine. Ms. B’s current medications are dextromethorphan/bupropion 45/105 mg twice daily and aripiprazole 5 mg/d, which she has taken for 3 months. She states she has “been on every antidepressant there is.”

When clinicians review Ms. B’s medication history, it is clear she has had adequate trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), intranasal esketamine, multiple augmentation strategies, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Ms. B seeks an alternative medication to improve her depressive symptoms.

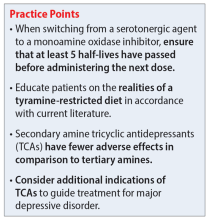

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is commonly defined as depression that has not responded to ≥2 adequate trials of an antidepressant.1 Some guidelines recommend monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as second- or even third-line options for MDD,2 while others recommend reserving them for patients with insufficient responses to alternative treatment modalities.3,4 Although MAOIs and TCAs have been available since the 1950s, prescribing these medications has become less prevalent due to safety concerns, the availability of other pharmacologic options, and a lack of clinical training and comfort.5,6 Most research notes that MAOIs are superior for treating atypical depression while TCAs are more effective for melancholic depression.2-4 In a review of 20 studies, Thase et al7 found that 50% of TCA nonresponders benefited from an MAOI. In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, monotherapy with the MAOI tranylcypromine was associated with a lower remission rate than the TCA nortriptyline; many argue the dose of tranylcypromine was suboptimal, and few participants completed an adequate trial in the last level.8,9 A more recent study by Kim et al10 found MAOIs to be “generally more effective” than TCAs for TRD, particularly in patients with fewer antidepressant trials; however, this was a small retrospective exploratory trial. A network meta-analysis found both classes to be “competitive” with SSRIs based on efficacy and tolerability, which leads to the question of whether these medications should be considered earlier in therapy.11 Considering patient-specific factors and particular medication properties is an effective strategy when prescribing an MAOI or TCA.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

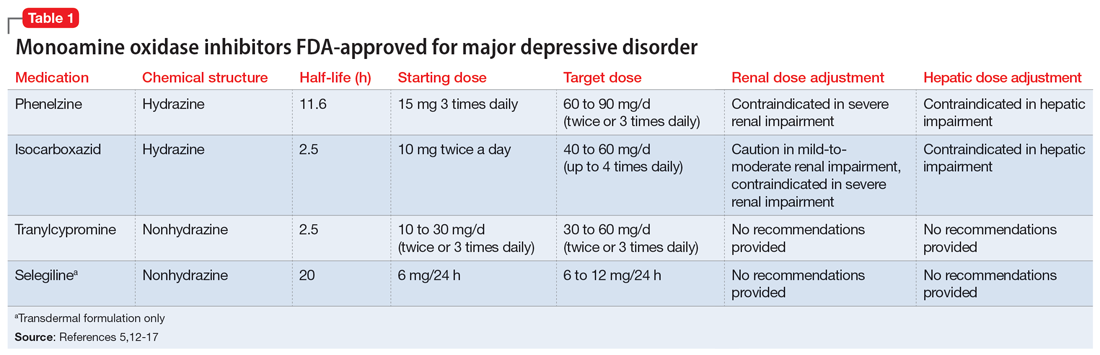

Four MAOIs are FDA-approved for treating MDD (Table 15,12-17): phenelzine, isocarboxazid, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. These medications irreversibly inhibit MAO, which exists as isomers A and B. MAO-A primarily metabolizes serotonin and norepinephrine, which is largely responsible for these medications’ antidepressant effects. Both isomers equally metabolize dopamine.5,12,18 It is best to avoid using MAOIs in patients with cerebrovascular disease, hepatic disease, or pheochromocytoma. Patients with active substance use disorders (particularly sympathomimetics and hallucinogens) are at an increased risk for hypertensive crises and serotonin syndrome, respectively. The most common adverse effects are orthostatic hypotension (despite more well-known concerns regarding hypertension), alterations in sleep patterns (insomnia or hypersomnia, depending on the agent), gastrointestinal issues, and anticholinergic adverse effects such as dry mouth and constipation.13,19-21

In one review and meta-analysis, phenelzine displayed the highest efficacy across all MAOIs.11 It likely requires high doses to achieve adequate MAO inhibition.11 A metabolite of phenelzine inhibits gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase and may be helpful for patients with comorbid anxiety disorders or MDD with anxious distress.18,21 Additional considerations include phenelzine’s propensity for orthostasis (with rapid titrations and higher doses), sedation, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and a rare adverse effect of vitamin B6 deficiency.5,13,14,20-22

Use of isocarboxazid in clinical practice is rare. Its adverse effects are similar to those of phenelzine but isocarboxazid is less studied. Tranylcypromine has a similar chemical structure to amphetamine. It can be stimulating at higher doses, potentially benefitting patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or significant apathy.13,23 Selegiline’s distinct quality is its availability as a transdermal patch, which may be useful for patients who struggle to take oral medications. At low doses (6 mg/24 h), the selegiline transdermal patch allows patients to disregard a dietary tyramine restriction because it avoids first-pass metabolism. It inhibits both MAO isomers in the brain but is only selective for MAO-B once concentrations are distributed to the liver. Higher doses require a tyramine-restricted diet because there is still some MAO-A inhibition in the gut. Selegiline is also stimulating because it is converted to amphetamine and methamphetamine.5,12,13,17,19,24

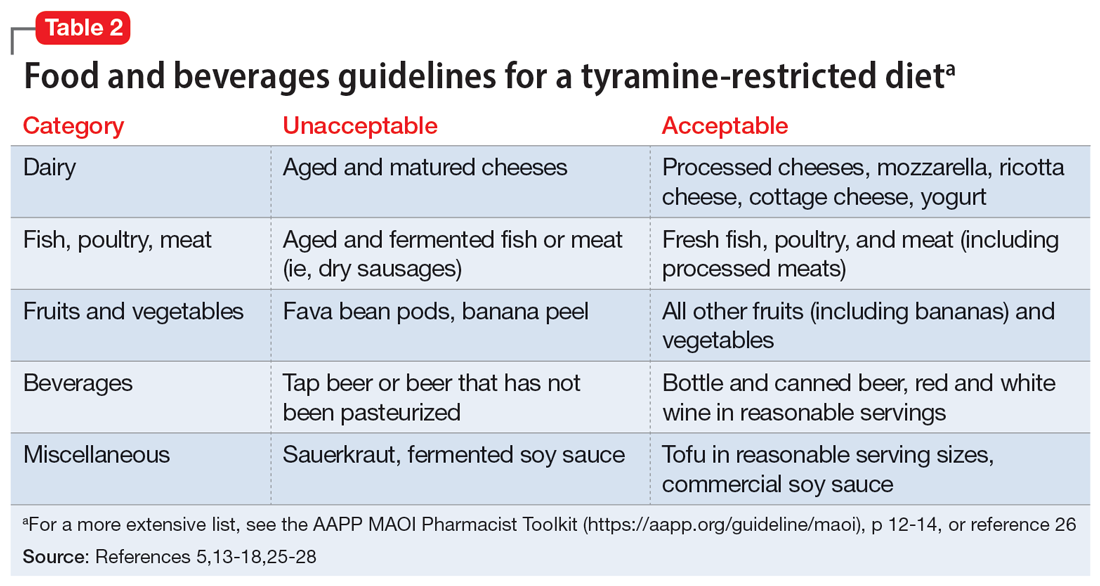

Despite promising results from the use of MAOIs, physicians and patients may be reluctant to use these medications due to perceived limitations. One prominent barrier is the infamous “cheese reaction.” Tyramine, an amino acid found in certain food and beverages (Table 25,13-18,25-28), is broken down by MAO-A in the gut. When this enzyme is inhibited, higher concentrations of tyramine reach systemic circulation. Tyramine’s release of norepinephrine (which now cannot be broken down) can lead to a hypertensive crisis. Consequently, a tyramine-restricted diet is recommended for patients taking an MAOI. However, the common notion that cheese, wine, and beer must be avoided is false, because most of the dietary restrictions developed following the discovery of MAOIs are antiquated.5,12,25-28 Patients who take an MAOI only need to slightly adjust their diet, as outlined in Table 2.5,13-18,25-28 A reasonable serving size of most foods and beverages containing tyramine is unlikely to elicit this “pressor” response. Of the 4 MAOIs FDA-approved for MDD, tranylcypromine appears to be the most sensitive to tyramine.21 Transient postdose hypertension (regardless of tyramine) may occur after taking an MAOI.29 Encourage patients to monitor their blood pressure.

Continue to: Additional hurdles include...