ESTES PARK, COLO. – Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is a common and treatable psychiatric condition the diagnosis of which is made more challenging because the disorder looks different than the classic picture in children.

Trying to apply the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to adults is problematic. The DSM-IV symptoms focus mainly on childhood activities, particularly school and play. Plus, hyperactivity – the most recognizable symptom of ADHD in childhood – tends to diminish with age, becoming a more subjective experience of internal restlessness, Dr. Robert D. Davies explained at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Yet ADHD by definition always first develops in childhood, even if an affected adult hasn’t previously been diagnosed and doesn’t recall the early impairment.

"Very often patients first present in adulthood because things have changed in their life, but if you go back and look carefully, it has been there since childhood. If you have a patient who comes in saying, ‘In the last few years all of a sudden I can’t concentrate, I can’t focus, I’m not doing well at work’ and there’s never been any hint of that before, I don’t know what it is, but it’s not ADHD," declared Dr. Davies, a psychiatrist at the university.

The adult presentation of ADHD is more subtle than in children. It includes disorganization and poor time-management skills; impulsivity with poor self-control often demonstrated via rude comments and frequent interruption of others; emotional difficulties rooted in low self-esteem and poor affect regulation; and difficulty in concentrating and completing even simple tasks.

"Adults with ADHD make great salespeople. They can really close the sale. But I’ve had so many salespeople I’ve treated who are failing at work because they never get the paperwork in and actually file the order. They don’t follow up on those things, but they’re great at the beginning," he observed.

The hyperactivity component can look much like mania: thrill seeking, racing thoughts, excessive talking, and difficulty in falling asleep.

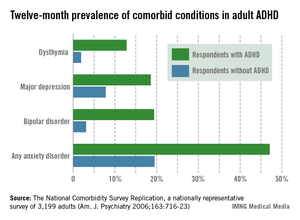

All these adult ADHD symptoms add up to increased risks of divorce, difficulties at work, substance abuse, incarceration, a poor driving history – "lots of fender benders," according to Dr. Davies – and high rates of comorbid depression and anxiety that have been well documented in a landmark national study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. The study, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, placed the prevalence of adult ADHD among the general population at 4.4% (see accompanying graphic).

Substance abuse, hearing loss, and hyperthyroidism need to be ruled out before arriving at the diagnosis of adult ADHD. More challenging is to sort out adult ADHD from several commonly comorbid psychiatric conditions, most notably bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and personality disorder.

The patient’s sleep pattern can provide useful information in this regard. Adult ADHD is characterized by a phase shift: The internal hyperactivity leads to difficulty in falling asleep until quite late, with subsequent trouble in waking up in the morning. In contrast, the manic phase of bipolar disorder is marked by a decreased sleep requirement. Patients with generalized anxiety disorder, unlike those with bipolar mania, really need their sleep, but their difficulty in falling asleep stems from worries about what might happen in the future. Individuals with adult ADHD typically can’t sleep because they’re ruminating about mistakes they’ve made.

"They’re worried about things that are real: what they forgot to do, who they’ve offended. In contrast, anytime you’re talking to a patient and they’re saying a lot of ‘what ifs,’ that’s a clue that the problem is generalized anxiety disorder," he explained.

While ADHD is a lifelong condition that begins in childhood, bipolar disorder is episodic and starts in the late teen years or later.

As for the differential between adult ADHD and borderline personality disorder, patients with ADHD typically have a sense of self as being harmed by their own failures and shortcomings coupled with the negative way others perceive them. In contrast, individuals with personality disorders often don’t have any real sense of self. The chaotic life that figures so prominently in the personal histories of many patients with adult ADHD dates back to childhood and results from their impulsivity and inattention, whereas the chaotic life of the patient with borderline personality disorder often starts in adolescence and is the result of their poor interpersonal relationships and rigid thinking.

Lots of adults are coming to the offices of primary care physicians and psychiatrists seeking help for what they believe is ADHD, brandishing their scores on self-report screening scales they find in popular magazines. Dr. Davies advises not attaching much weight to the self-report scales.