User login

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Improving statewide reporting of melanoma cases

For years, . I have audited my melanoma cases (biopsies and excisions sent to me) and discovered that of the 240 cases confirmed over the past 5 years, only 41 were reported to the Ohio state health department and are in that database. That amounts to 199 unreported cases – nearly 83% of the total.

This raises the question as to who is responsible for reporting these cases. Dermatology is unique in that our pathology specimens are not routinely passed through a hospital pathology laboratory. The big difference in reporting is that hospital labs have trained data registrars to report all reportable cancers to state health departments. Therefore, in my case, only patients sent to a hospital-based surgeon for sentinel node biopsies or exceptionally large excisions get reported. When I have spoken about this to my dermatology lab and biopsying physicians, the discussion rapidly turns into a finger pointing game of who is responsible. No one, except perhaps the dermatologist who did the biopsy, has all the data.

Unfortunately, these cases are tedious and time consuming to report. Despite state laws requiring reporting, even with penalties for nonreporters, many small dermatology practices do not report these cases and expect their dermatopathology labs to do so, but the labs expect the biopsying dermatologist to report the cases. This is a classic case of an unfunded mandate since small dermatology practices do not have the time or resources for reporting.

I have worked with the Ohio Department of Health to remove any unnecessary data fields and they have managed to reduce the reporting fields (to 59!). This is the minimum amount required to be included in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database. Many of these fields are not applicable to thin melanomas and after reviewing the 1-hour online training course, each patient can be entered (once the necessary data are collected) in about 15 minutes. This is still a formidable task for small offices, which cannot be blamed for ducking and hoping someone else reports.

While there is controversy regarding the relevance of thin melanomas to overall survival, more accurate reporting can only bolster either argument.

A solution to underreporting

I believe we have developed a unique solution to this conundrum. Our office is partnering with the local melanoma support group (Melanoma Know More) to train volunteers to help with the data collection and reporting of these thin melanomas. We have also discovered that the local community college has students who are majoring in pathology data registry reporting and are happy to gain a little experience before graduating.

We eventually hope to become a clearinghouse for the entire state of Ohio. The state health department has agreed not to apply punitive measures to physicians who are new reporters. It is our plan to obtain melanoma pathology reports, run these past the state database, identify unreported cases, and obtain further data as needed from the biopsying physicians, and then complete the reporting.

I think dermatologic oncologists in every state should view this as an opportunity for a significant quality improvement project, and as a terrific service to the general dermatology community.

The ramifications of more comprehensive reporting of melanomas are great. I would expect more attention to the disease by researchers, and much more clout with state and national legislators. Think about increased funding for melanoma research, allowing sunscreen use for school children, sunshades for playgrounds, and more responsible tanning bed restrictions.

Now, I must inform you that this is my last column, but I plan to continue writing. Over the past 6 years, I have been able to cover a wide range of topics ranging from human trafficking and the American Medical Association, to the many problems faced by small practices. I have enjoyed myself hugely. To quote Douglas Adams, from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “So long and thanks for all the fish!” Keep in touch at bcoldiron@gmail.com.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

For years, . I have audited my melanoma cases (biopsies and excisions sent to me) and discovered that of the 240 cases confirmed over the past 5 years, only 41 were reported to the Ohio state health department and are in that database. That amounts to 199 unreported cases – nearly 83% of the total.

This raises the question as to who is responsible for reporting these cases. Dermatology is unique in that our pathology specimens are not routinely passed through a hospital pathology laboratory. The big difference in reporting is that hospital labs have trained data registrars to report all reportable cancers to state health departments. Therefore, in my case, only patients sent to a hospital-based surgeon for sentinel node biopsies or exceptionally large excisions get reported. When I have spoken about this to my dermatology lab and biopsying physicians, the discussion rapidly turns into a finger pointing game of who is responsible. No one, except perhaps the dermatologist who did the biopsy, has all the data.

Unfortunately, these cases are tedious and time consuming to report. Despite state laws requiring reporting, even with penalties for nonreporters, many small dermatology practices do not report these cases and expect their dermatopathology labs to do so, but the labs expect the biopsying dermatologist to report the cases. This is a classic case of an unfunded mandate since small dermatology practices do not have the time or resources for reporting.

I have worked with the Ohio Department of Health to remove any unnecessary data fields and they have managed to reduce the reporting fields (to 59!). This is the minimum amount required to be included in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database. Many of these fields are not applicable to thin melanomas and after reviewing the 1-hour online training course, each patient can be entered (once the necessary data are collected) in about 15 minutes. This is still a formidable task for small offices, which cannot be blamed for ducking and hoping someone else reports.

While there is controversy regarding the relevance of thin melanomas to overall survival, more accurate reporting can only bolster either argument.

A solution to underreporting

I believe we have developed a unique solution to this conundrum. Our office is partnering with the local melanoma support group (Melanoma Know More) to train volunteers to help with the data collection and reporting of these thin melanomas. We have also discovered that the local community college has students who are majoring in pathology data registry reporting and are happy to gain a little experience before graduating.

We eventually hope to become a clearinghouse for the entire state of Ohio. The state health department has agreed not to apply punitive measures to physicians who are new reporters. It is our plan to obtain melanoma pathology reports, run these past the state database, identify unreported cases, and obtain further data as needed from the biopsying physicians, and then complete the reporting.

I think dermatologic oncologists in every state should view this as an opportunity for a significant quality improvement project, and as a terrific service to the general dermatology community.

The ramifications of more comprehensive reporting of melanomas are great. I would expect more attention to the disease by researchers, and much more clout with state and national legislators. Think about increased funding for melanoma research, allowing sunscreen use for school children, sunshades for playgrounds, and more responsible tanning bed restrictions.

Now, I must inform you that this is my last column, but I plan to continue writing. Over the past 6 years, I have been able to cover a wide range of topics ranging from human trafficking and the American Medical Association, to the many problems faced by small practices. I have enjoyed myself hugely. To quote Douglas Adams, from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “So long and thanks for all the fish!” Keep in touch at bcoldiron@gmail.com.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

For years, . I have audited my melanoma cases (biopsies and excisions sent to me) and discovered that of the 240 cases confirmed over the past 5 years, only 41 were reported to the Ohio state health department and are in that database. That amounts to 199 unreported cases – nearly 83% of the total.

This raises the question as to who is responsible for reporting these cases. Dermatology is unique in that our pathology specimens are not routinely passed through a hospital pathology laboratory. The big difference in reporting is that hospital labs have trained data registrars to report all reportable cancers to state health departments. Therefore, in my case, only patients sent to a hospital-based surgeon for sentinel node biopsies or exceptionally large excisions get reported. When I have spoken about this to my dermatology lab and biopsying physicians, the discussion rapidly turns into a finger pointing game of who is responsible. No one, except perhaps the dermatologist who did the biopsy, has all the data.

Unfortunately, these cases are tedious and time consuming to report. Despite state laws requiring reporting, even with penalties for nonreporters, many small dermatology practices do not report these cases and expect their dermatopathology labs to do so, but the labs expect the biopsying dermatologist to report the cases. This is a classic case of an unfunded mandate since small dermatology practices do not have the time or resources for reporting.

I have worked with the Ohio Department of Health to remove any unnecessary data fields and they have managed to reduce the reporting fields (to 59!). This is the minimum amount required to be included in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database. Many of these fields are not applicable to thin melanomas and after reviewing the 1-hour online training course, each patient can be entered (once the necessary data are collected) in about 15 minutes. This is still a formidable task for small offices, which cannot be blamed for ducking and hoping someone else reports.

While there is controversy regarding the relevance of thin melanomas to overall survival, more accurate reporting can only bolster either argument.

A solution to underreporting

I believe we have developed a unique solution to this conundrum. Our office is partnering with the local melanoma support group (Melanoma Know More) to train volunteers to help with the data collection and reporting of these thin melanomas. We have also discovered that the local community college has students who are majoring in pathology data registry reporting and are happy to gain a little experience before graduating.

We eventually hope to become a clearinghouse for the entire state of Ohio. The state health department has agreed not to apply punitive measures to physicians who are new reporters. It is our plan to obtain melanoma pathology reports, run these past the state database, identify unreported cases, and obtain further data as needed from the biopsying physicians, and then complete the reporting.

I think dermatologic oncologists in every state should view this as an opportunity for a significant quality improvement project, and as a terrific service to the general dermatology community.

The ramifications of more comprehensive reporting of melanomas are great. I would expect more attention to the disease by researchers, and much more clout with state and national legislators. Think about increased funding for melanoma research, allowing sunscreen use for school children, sunshades for playgrounds, and more responsible tanning bed restrictions.

Now, I must inform you that this is my last column, but I plan to continue writing. Over the past 6 years, I have been able to cover a wide range of topics ranging from human trafficking and the American Medical Association, to the many problems faced by small practices. I have enjoyed myself hugely. To quote Douglas Adams, from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “So long and thanks for all the fish!” Keep in touch at bcoldiron@gmail.com.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Should I get a COVID-19 booster shot?

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Inflation will be the end of medicine

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

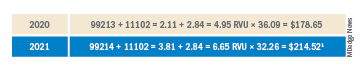

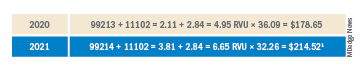

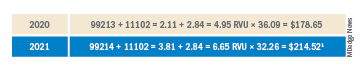

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Price transparency comes to medicine

There is a Chinese curse which says “May he live in interesting times.” Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history.

–Robert Kennedy, Cape Town, South Africa, 1966

Well, you may not know it, but price transparency is coming to medicine, including dermatology. . It has survived a challenge by the American Hospital Association in federal court, which generally means it is going to “stick.” Its effects should start to appear on Jan. 1, 2022.

The newly finalized rule will require insurers to publicly disclose in-network provider-negotiated rates, historical out-of-network allowed amounts, associated facility fees, and drug-pricing information in easily accessible machine-readable files. This information will be disclosed for the 500 most commonly billed physician services starting Jan. 1, 2022, and expanded to include all services the following year. Understand that you, as a practitioner, do not have to do anything, as insurers will do it for you, but your charge data will be on display. It is not clear if there is an appeal mechanism for physicians to correct erroneous data.

This should provide a fascinating look at just what things really cost, and may prove, as we suspect, small practices are less expensive. Important exemptions to reporting include emergency services, anesthesia, lab tests, and pathology fees, which will not be required, but recommended, to be disclosed.

Bear in mind that this rule was not designed to benefit physicians or hospitals, but rather to allow patients to comparison shop and drive down the cost of medical care. True price transparency may well accomplish this, particularly in our age of sky-high deductibles, if the information is accurate and readily accessible.

Although studies of patient behavior have shown that few patients actually use price comparison tools, the data required to be publicly disclosed and accessible will make this much easier. The Wall Street Journal or ProPublica will likely be all over this with applications to make comparisons easier. Still, many patients are price insensitive, particularly if they are Medicare recipients and only responsible for a nominal deductible.

Almost all the evaluation and management codes, as well as many dermatology procedure codes, are listed in the top 500 items and services included in the initial stage of the finalized rule. These include skin biopsies, destructions, drainages, several different benign and malignant excisions and, of course, Mohs surgery (but only the first stage, the 2nd stage will be listed in 2023).

While it is unlikely for patients to doctor shop for services that are performed on the same day as the office visit, such as a biopsies or destructions, we would expect comparisons for more expensive, planned procedures such as Mohs surgery and cancer excisions. Considering the rule, Mohs surgery may compare favorably to excisions performed in the hospital if the operating room charges are included, but not so well if the pathology and anesthesia charges are not included in the cost. It is inherently unfair to compare Mohs to excision in an operating room since the Mohs procedure has the anesthesia and pathology work embedded in the code (at 55% of the value of the code), and the multiple frozen sections taken by the surgeon in the operating room will not be listed as they are technically considered to be exempt additional pathology services.

This could put the Mohs surgeon in the interesting position of billing for excisions and frozen sections instead of Mohs surgery in order to compete with the hospital-based surgeon. This is not unbundling, if overall charges are lower and if distinctly different procedures are followed and different paperwork is generated. This is how I currently handle patients who demand Mohs surgery for inappropriate sites.

The effect on hospital groups that can charge facility fees could be quite dramatic, as it could be on large groups and on private equity groups who may have negotiated better rates. These increased costs will be revealed to consumers. In January 2023, the insurers will have to deploy a tool on their web site, updated monthly, that details rates for the 500 most common procedures for all in- and out-of-network providers and how much the patient can expect to pay out of pocket. All facility fees for procedures will be included. As noted earlier, we would expect third parties to already have done this. The historical and current costs for medications will also be included, which should make for interesting times in the pharmaceutical industry.

In January 2024, insurers will be required to post all the additional codes they cover, including complex closures, flaps, and grafts and any associated facility fees. Of course, a patient or a surgeon does not know what sort of repair a patient will need after Mohs surgery, but with high deductibles hitting harder, we would expect more patients requesting healing by second intent.

Whether these price comparisons will drive patients from relatively high-cost centers to less costly ones is unclear. This has certainly been the case for MRI and CT imaging. Price transparency for MRIs increased use of less costly providers and triggered provider competition.

Whether the price differentials will allow smaller practices some leverage in negotiating rates is also uncertain. Who knows, perhaps the out-of-network rate is greater than what your contract currently specifies, which could spur you to drop their network entirely. There may be great opportunity here for the smaller practitioner who has been boxed out of the big-group pricing and networks.

Be prepared in January 2022, to discuss these issues with patients and insurers, and be sure to check where you fall in cost comparisons. What possible logic could an insurer have for excluding you from a network where your average charges are less than their current panel? As noted before, this may be a boon for small practices that have been forced to the fringes of reimbursement and an opportunity to demonstrate that they are really much less expensive. We live in interesting times.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr. Bishop is doing a fellowship in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology with Dr. Coldiron at the Skin Cancer Center in Cincinnati. Write to Dr. Coldiron at dermnews@mdedge.com.

There is a Chinese curse which says “May he live in interesting times.” Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history.

–Robert Kennedy, Cape Town, South Africa, 1966

Well, you may not know it, but price transparency is coming to medicine, including dermatology. . It has survived a challenge by the American Hospital Association in federal court, which generally means it is going to “stick.” Its effects should start to appear on Jan. 1, 2022.

The newly finalized rule will require insurers to publicly disclose in-network provider-negotiated rates, historical out-of-network allowed amounts, associated facility fees, and drug-pricing information in easily accessible machine-readable files. This information will be disclosed for the 500 most commonly billed physician services starting Jan. 1, 2022, and expanded to include all services the following year. Understand that you, as a practitioner, do not have to do anything, as insurers will do it for you, but your charge data will be on display. It is not clear if there is an appeal mechanism for physicians to correct erroneous data.

This should provide a fascinating look at just what things really cost, and may prove, as we suspect, small practices are less expensive. Important exemptions to reporting include emergency services, anesthesia, lab tests, and pathology fees, which will not be required, but recommended, to be disclosed.

Bear in mind that this rule was not designed to benefit physicians or hospitals, but rather to allow patients to comparison shop and drive down the cost of medical care. True price transparency may well accomplish this, particularly in our age of sky-high deductibles, if the information is accurate and readily accessible.

Although studies of patient behavior have shown that few patients actually use price comparison tools, the data required to be publicly disclosed and accessible will make this much easier. The Wall Street Journal or ProPublica will likely be all over this with applications to make comparisons easier. Still, many patients are price insensitive, particularly if they are Medicare recipients and only responsible for a nominal deductible.

Almost all the evaluation and management codes, as well as many dermatology procedure codes, are listed in the top 500 items and services included in the initial stage of the finalized rule. These include skin biopsies, destructions, drainages, several different benign and malignant excisions and, of course, Mohs surgery (but only the first stage, the 2nd stage will be listed in 2023).

While it is unlikely for patients to doctor shop for services that are performed on the same day as the office visit, such as a biopsies or destructions, we would expect comparisons for more expensive, planned procedures such as Mohs surgery and cancer excisions. Considering the rule, Mohs surgery may compare favorably to excisions performed in the hospital if the operating room charges are included, but not so well if the pathology and anesthesia charges are not included in the cost. It is inherently unfair to compare Mohs to excision in an operating room since the Mohs procedure has the anesthesia and pathology work embedded in the code (at 55% of the value of the code), and the multiple frozen sections taken by the surgeon in the operating room will not be listed as they are technically considered to be exempt additional pathology services.

This could put the Mohs surgeon in the interesting position of billing for excisions and frozen sections instead of Mohs surgery in order to compete with the hospital-based surgeon. This is not unbundling, if overall charges are lower and if distinctly different procedures are followed and different paperwork is generated. This is how I currently handle patients who demand Mohs surgery for inappropriate sites.

The effect on hospital groups that can charge facility fees could be quite dramatic, as it could be on large groups and on private equity groups who may have negotiated better rates. These increased costs will be revealed to consumers. In January 2023, the insurers will have to deploy a tool on their web site, updated monthly, that details rates for the 500 most common procedures for all in- and out-of-network providers and how much the patient can expect to pay out of pocket. All facility fees for procedures will be included. As noted earlier, we would expect third parties to already have done this. The historical and current costs for medications will also be included, which should make for interesting times in the pharmaceutical industry.

In January 2024, insurers will be required to post all the additional codes they cover, including complex closures, flaps, and grafts and any associated facility fees. Of course, a patient or a surgeon does not know what sort of repair a patient will need after Mohs surgery, but with high deductibles hitting harder, we would expect more patients requesting healing by second intent.

Whether these price comparisons will drive patients from relatively high-cost centers to less costly ones is unclear. This has certainly been the case for MRI and CT imaging. Price transparency for MRIs increased use of less costly providers and triggered provider competition.

Whether the price differentials will allow smaller practices some leverage in negotiating rates is also uncertain. Who knows, perhaps the out-of-network rate is greater than what your contract currently specifies, which could spur you to drop their network entirely. There may be great opportunity here for the smaller practitioner who has been boxed out of the big-group pricing and networks.

Be prepared in January 2022, to discuss these issues with patients and insurers, and be sure to check where you fall in cost comparisons. What possible logic could an insurer have for excluding you from a network where your average charges are less than their current panel? As noted before, this may be a boon for small practices that have been forced to the fringes of reimbursement and an opportunity to demonstrate that they are really much less expensive. We live in interesting times.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Dr. Bishop is doing a fellowship in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology with Dr. Coldiron at the Skin Cancer Center in Cincinnati. Write to Dr. Coldiron at dermnews@mdedge.com.

There is a Chinese curse which says “May he live in interesting times.” Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history.

–Robert Kennedy, Cape Town, South Africa, 1966

Well, you may not know it, but price transparency is coming to medicine, including dermatology. . It has survived a challenge by the American Hospital Association in federal court, which generally means it is going to “stick.” Its effects should start to appear on Jan. 1, 2022.

The newly finalized rule will require insurers to publicly disclose in-network provider-negotiated rates, historical out-of-network allowed amounts, associated facility fees, and drug-pricing information in easily accessible machine-readable files. This information will be disclosed for the 500 most commonly billed physician services starting Jan. 1, 2022, and expanded to include all services the following year. Understand that you, as a practitioner, do not have to do anything, as insurers will do it for you, but your charge data will be on display. It is not clear if there is an appeal mechanism for physicians to correct erroneous data.

This should provide a fascinating look at just what things really cost, and may prove, as we suspect, small practices are less expensive. Important exemptions to reporting include emergency services, anesthesia, lab tests, and pathology fees, which will not be required, but recommended, to be disclosed.

Bear in mind that this rule was not designed to benefit physicians or hospitals, but rather to allow patients to comparison shop and drive down the cost of medical care. True price transparency may well accomplish this, particularly in our age of sky-high deductibles, if the information is accurate and readily accessible.

Although studies of patient behavior have shown that few patients actually use price comparison tools, the data required to be publicly disclosed and accessible will make this much easier. The Wall Street Journal or ProPublica will likely be all over this with applications to make comparisons easier. Still, many patients are price insensitive, particularly if they are Medicare recipients and only responsible for a nominal deductible.

Almost all the evaluation and management codes, as well as many dermatology procedure codes, are listed in the top 500 items and services included in the initial stage of the finalized rule. These include skin biopsies, destructions, drainages, several different benign and malignant excisions and, of course, Mohs surgery (but only the first stage, the 2nd stage will be listed in 2023).

While it is unlikely for patients to doctor shop for services that are performed on the same day as the office visit, such as a biopsies or destructions, we would expect comparisons for more expensive, planned procedures such as Mohs surgery and cancer excisions. Considering the rule, Mohs surgery may compare favorably to excisions performed in the hospital if the operating room charges are included, but not so well if the pathology and anesthesia charges are not included in the cost. It is inherently unfair to compare Mohs to excision in an operating room since the Mohs procedure has the anesthesia and pathology work embedded in the code (at 55% of the value of the code), and the multiple frozen sections taken by the surgeon in the operating room will not be listed as they are technically considered to be exempt additional pathology services.

This could put the Mohs surgeon in the interesting position of billing for excisions and frozen sections instead of Mohs surgery in order to compete with the hospital-based surgeon. This is not unbundling, if overall charges are lower and if distinctly different procedures are followed and different paperwork is generated. This is how I currently handle patients who demand Mohs surgery for inappropriate sites.