User login

COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider: An update

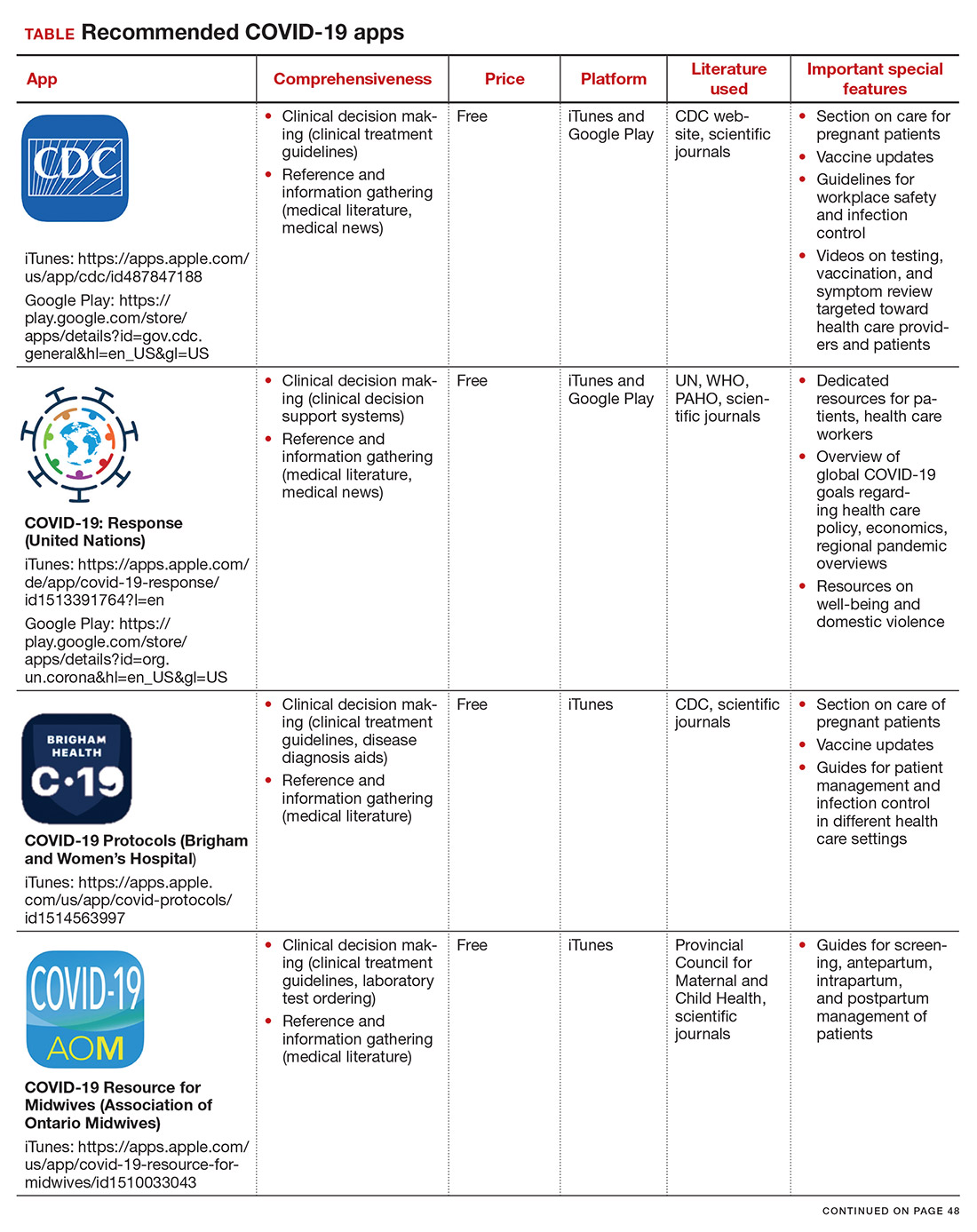

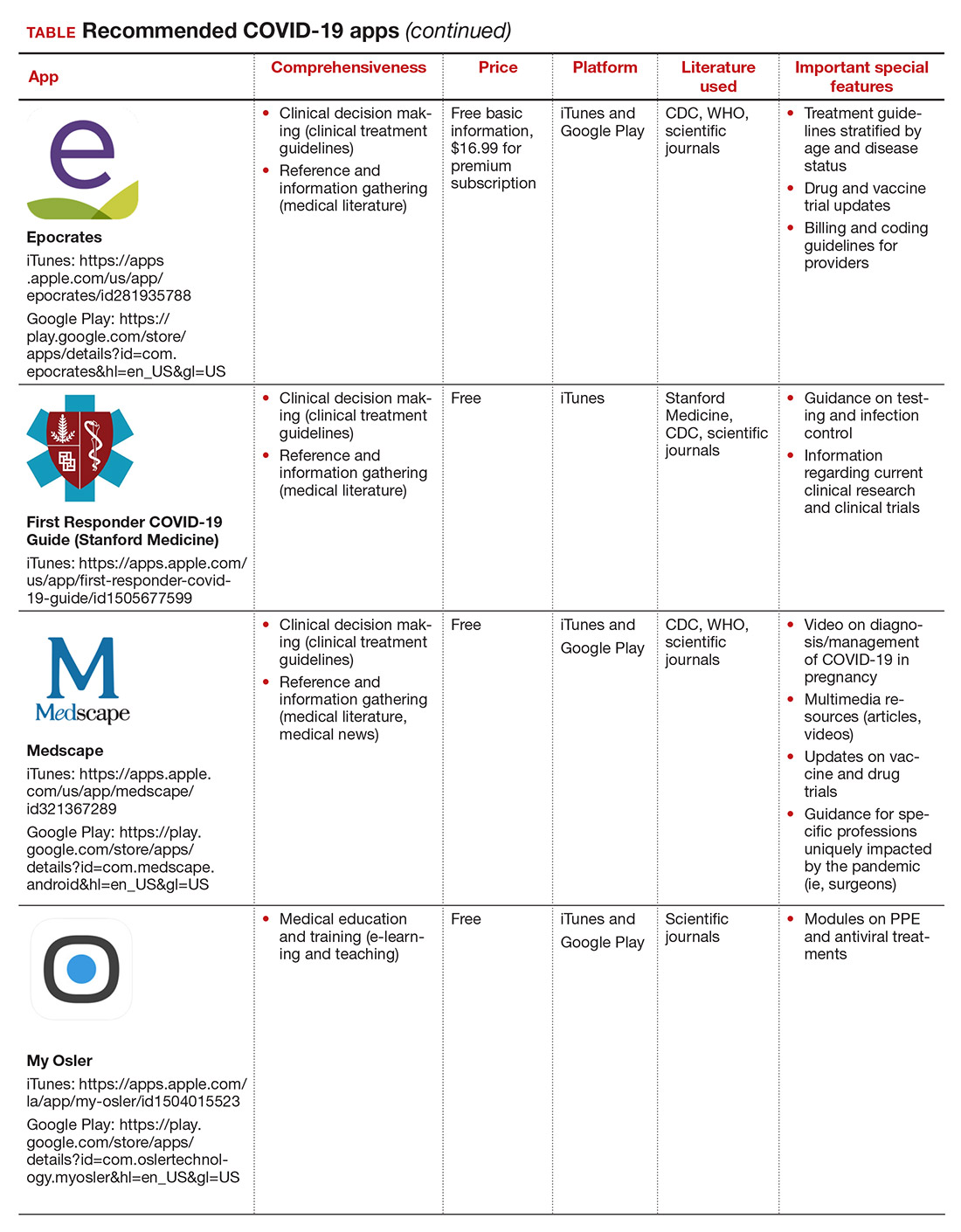

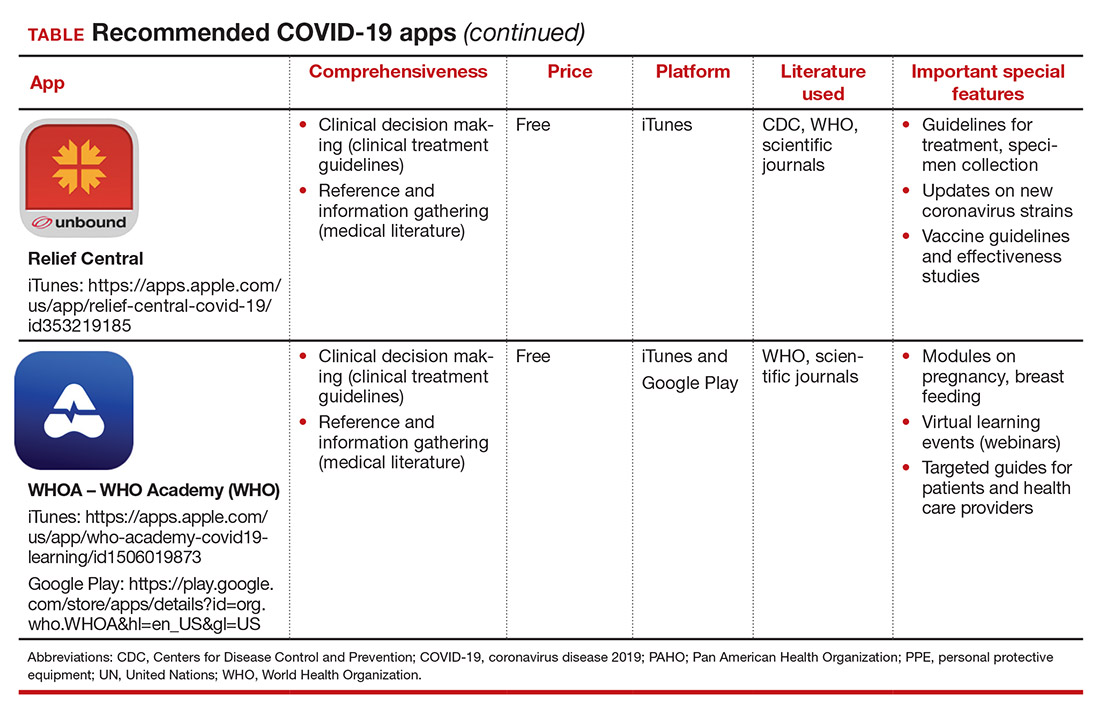

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

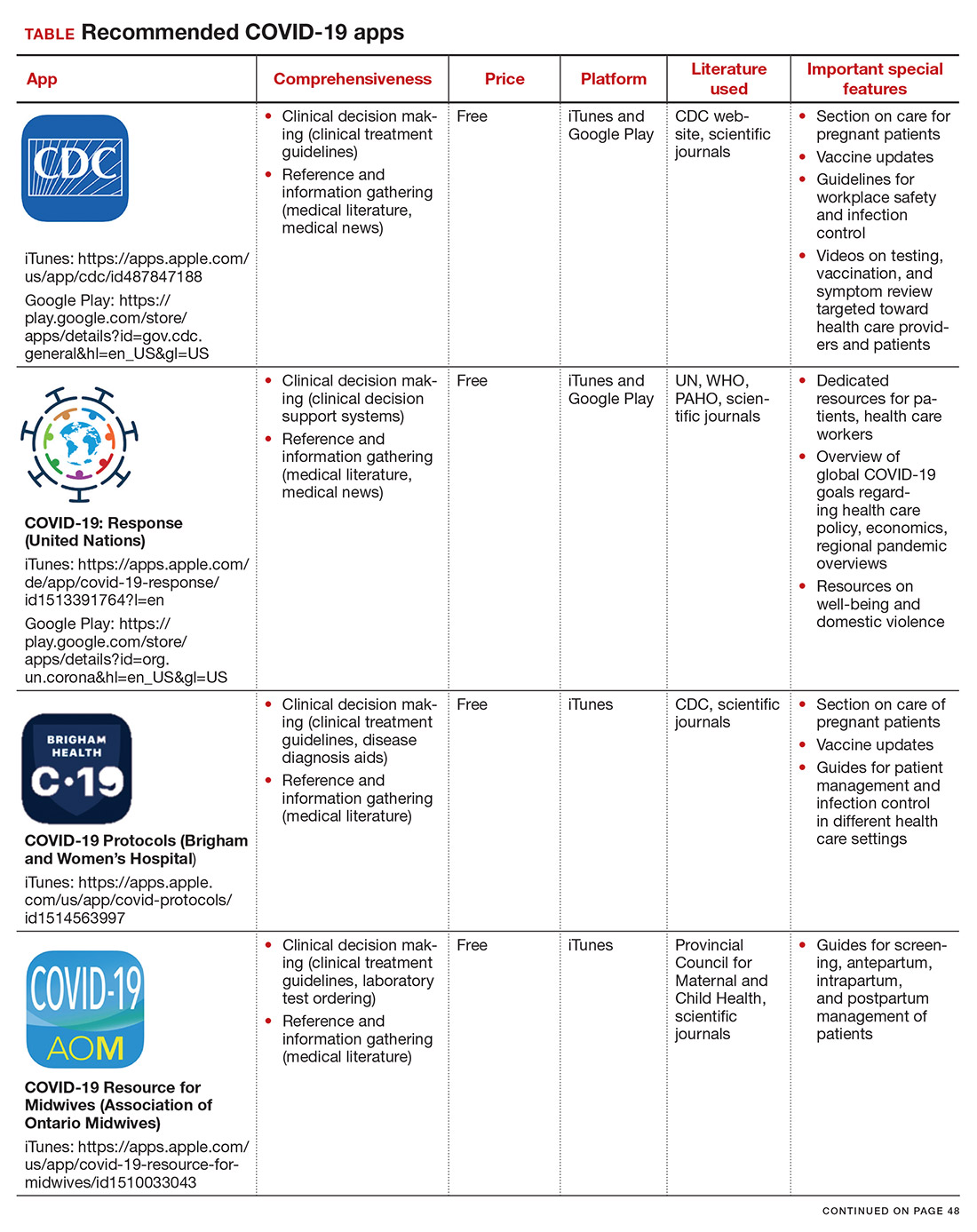

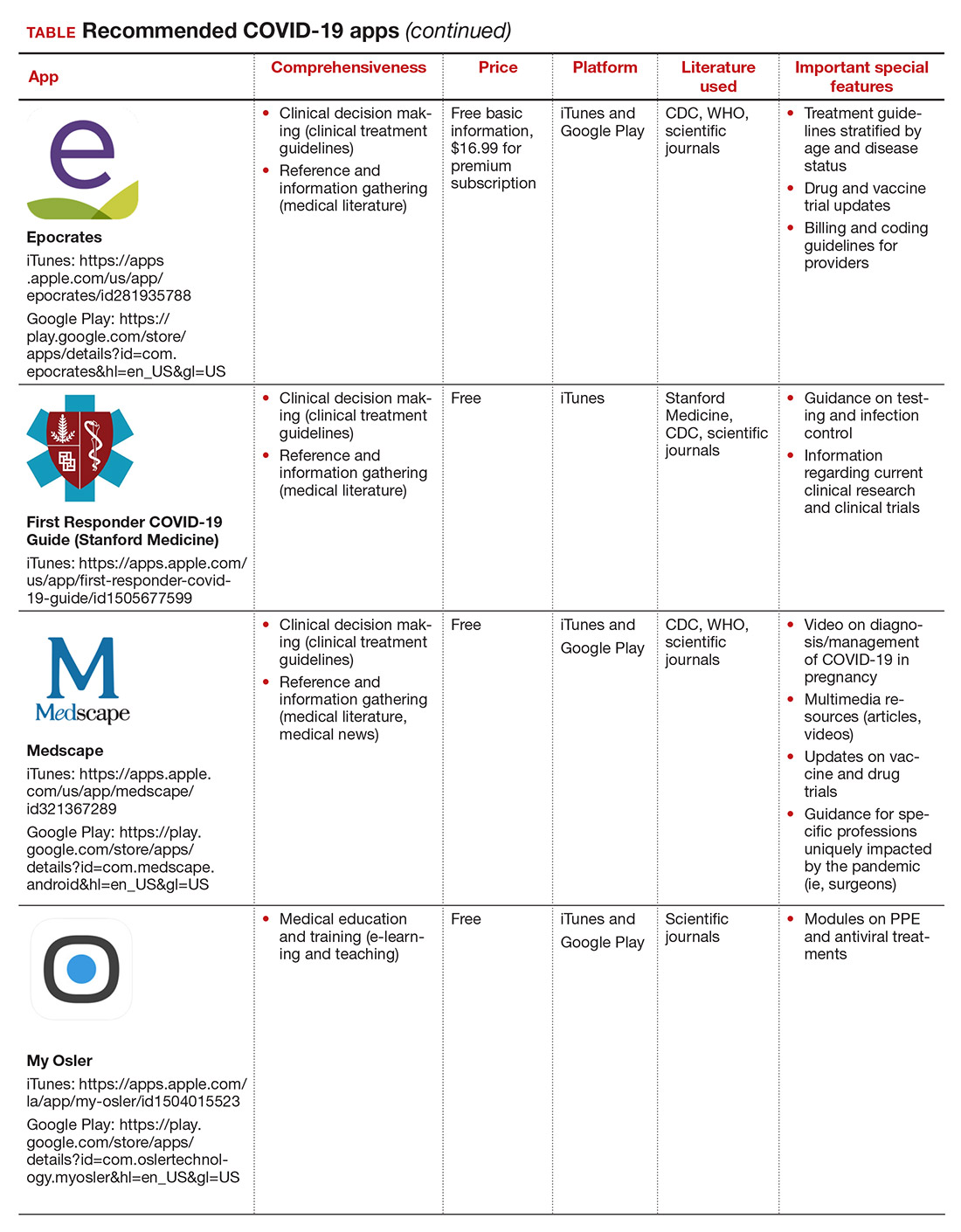

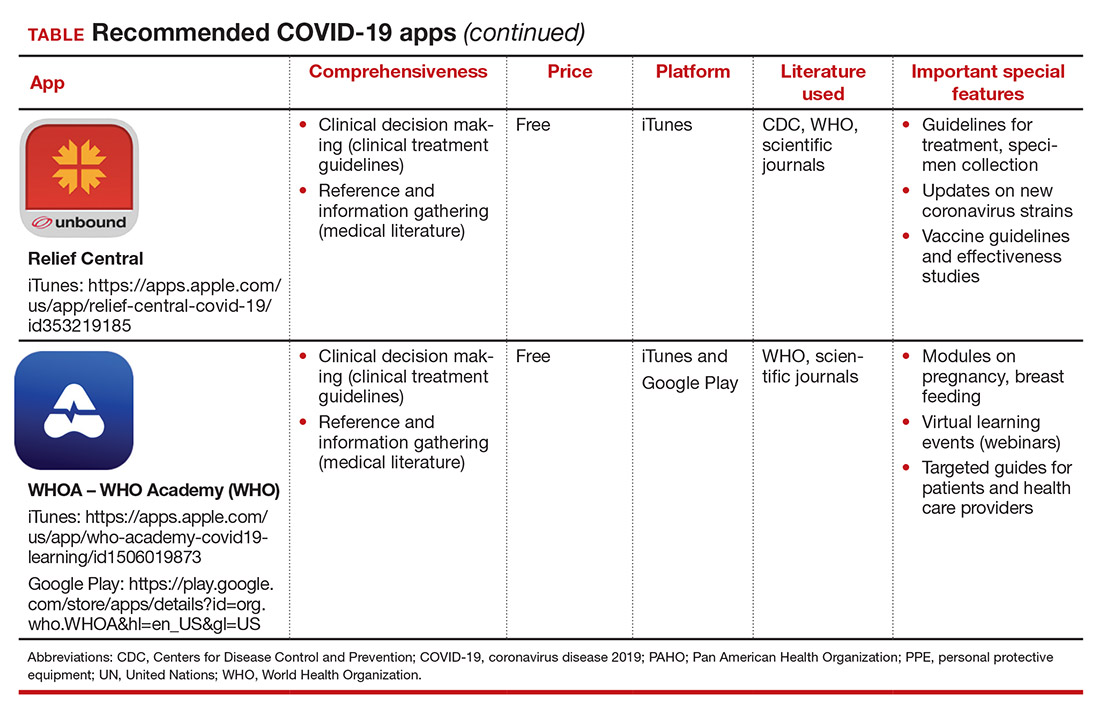

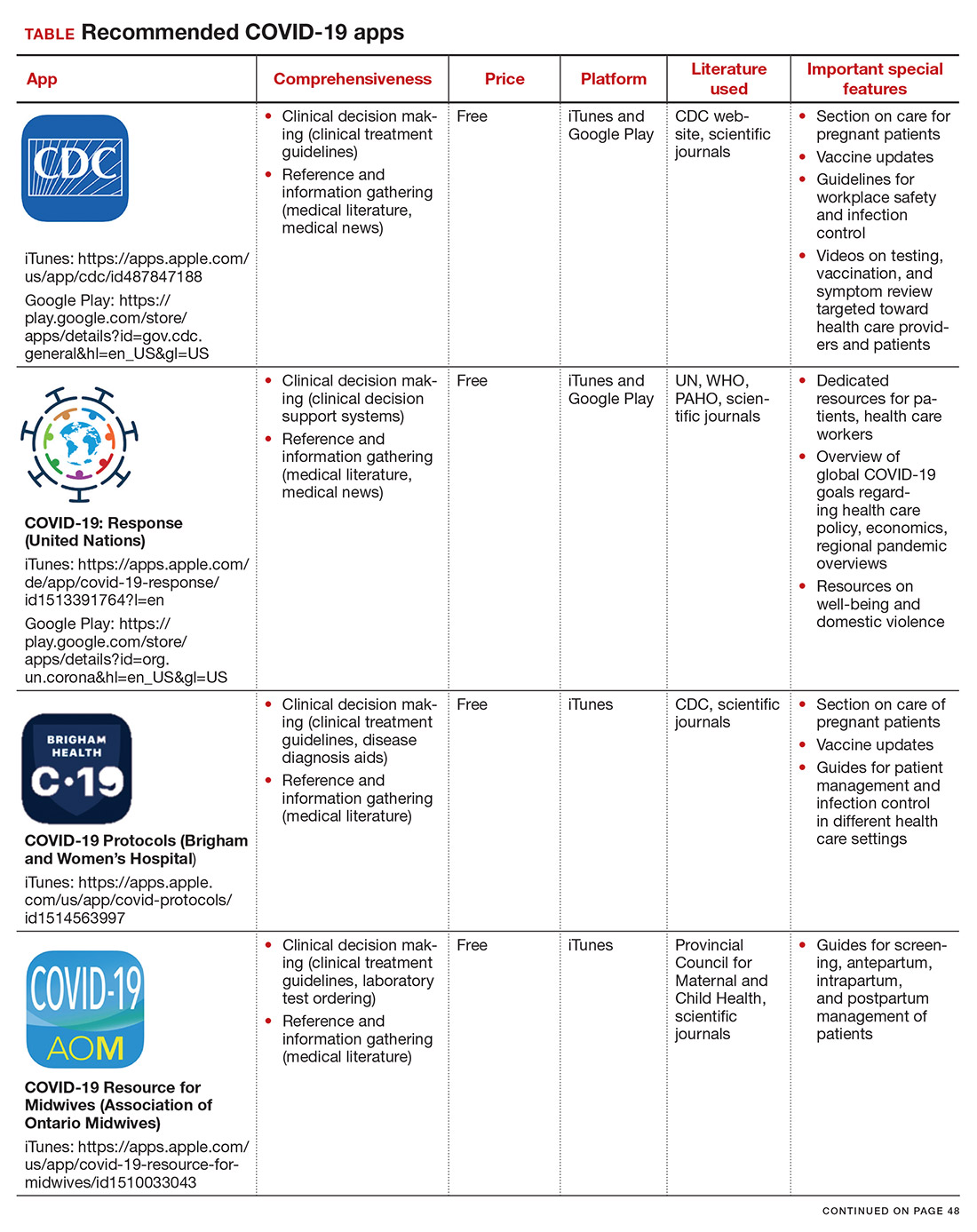

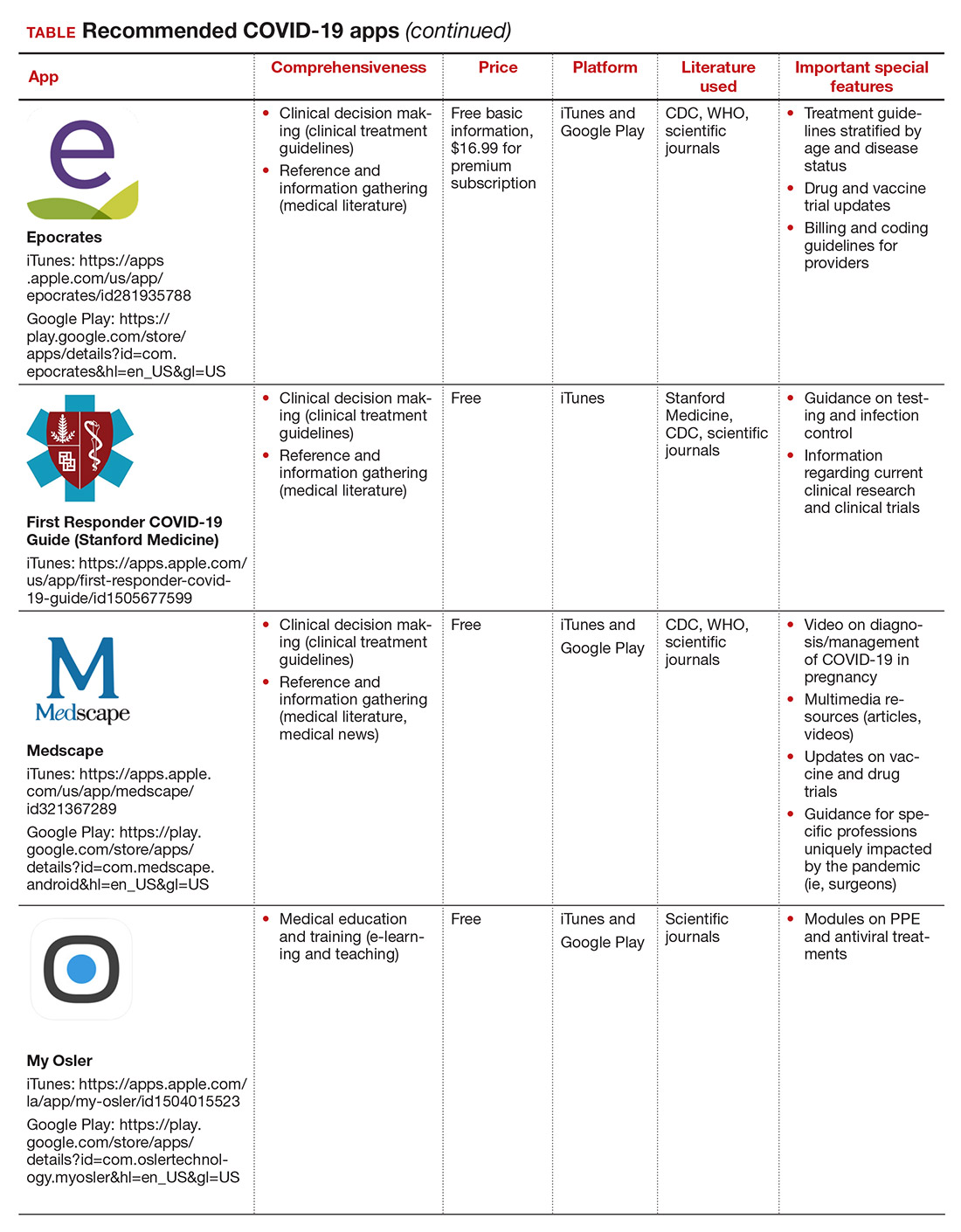

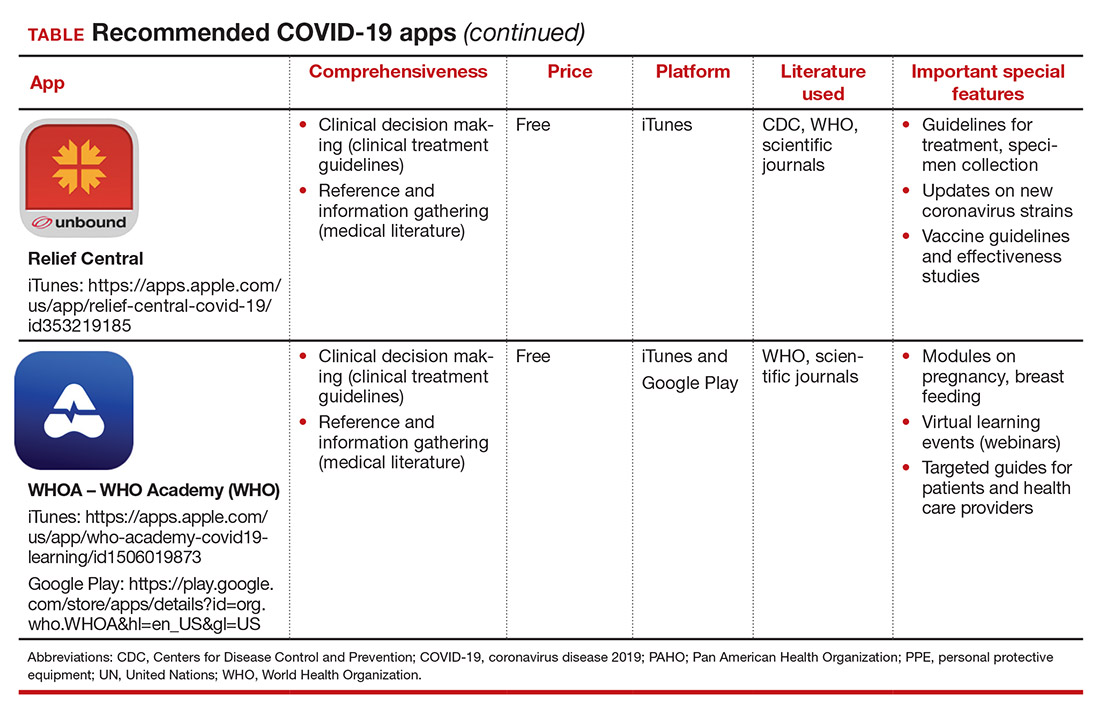

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

A case of BV during pregnancy: Best management approach

CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.

The vaginal microbiome is polymicrobial and has been classified into at least 5 community state types (CSTs). Four CSTs are dominated by lactobacilli. A fifth CST is characterized by the absence of lactobacilli and high concentrations of obligate or facultative anaerobes.1 The hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli predominate in normal vaginal flora and make up 70% to 90% of the total microbiome. These hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are associated with reduced vaginal proinflammatory cytokines and a highly acidic vaginal pH. Both factors defend against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2

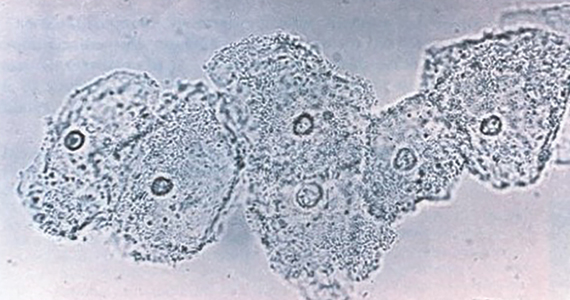

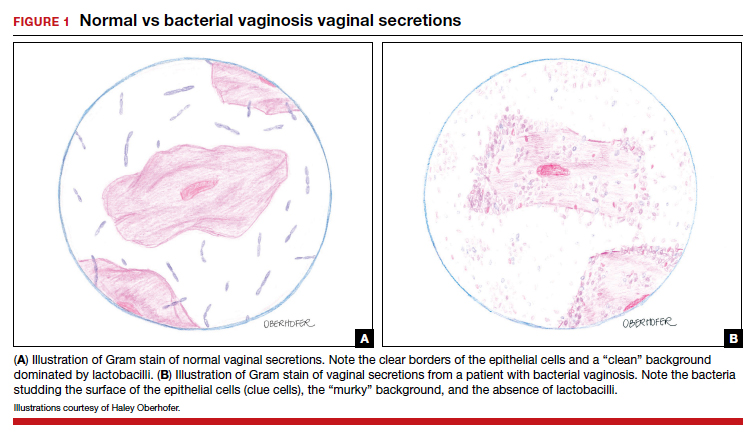

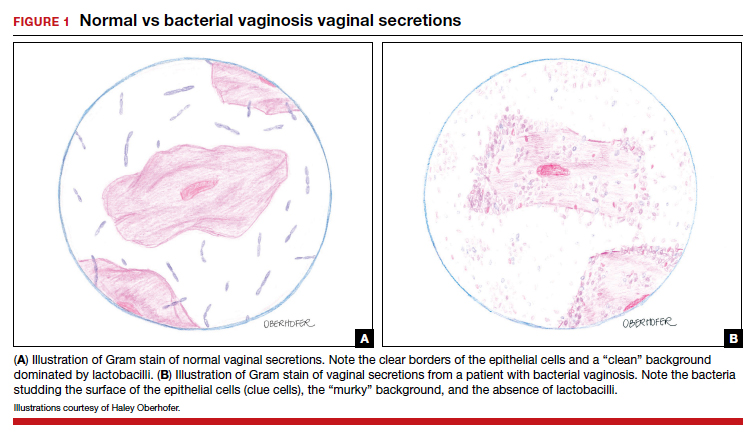

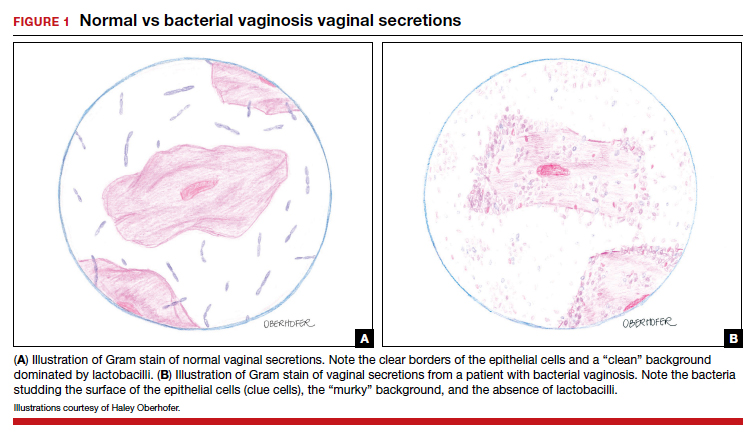

BV is a polymicrobial disorder marked by the significant reduction in the number of vaginal lactobacilli (FIGURE 1). A recent study showed that BV is associated first with a decrease in Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.3 The polymicrobial load is increased by a factor of up to 1,000, compared with normal vaginal flora.4 BV should be considered a biofilm infection caused by adherence of G vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium.5 This biofilm creates a favorable environment for the overgrowth of obligate anaerobic bacteria.

BMI factors into epidemiology

BV is the leading cause of vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated a prevalence of 29% in the general population and 50% in Black women aged 14 to 49 years.6 In 2013, Kenyon and colleagues performed a systematic review to assess the worldwide epidemiology of BV, and the prevalence varied by country. Within the US population, rates were highest among non-Hispanic, Black women.7 Brookheart and colleagues demonstrated that, even after controlling for race, overweight and obese women had a higher frequency of BV compared with leaner women. In this investigation, the overall prevalence of BV was 28.1%. When categorized by body mass index (BMI), the prevalence was 21.3% in lean women, 30.4% in overweight women, and 34.5% in obese women (P<.001). The authors also found that Black women had a higher prevalence, independent of BMI, compared with White women.8

Complications may occur. BV is notable for having several serious sequelae in both pregnant and nonpregnant women. For obstetric patients, these sequelae include an increased risk of preterm birth; first trimester spontaneous abortion, particularly in the setting of in vitro fertilization; intra-amniotic infection; and endometritis.9,10 The risk of preterm birth increases by a factor of 2 in infected women; however, most women with BV do not deliver preterm.4 The risk of endometritis is increased 6-fold in women with BV.11 Nonpregnant women with BV are at increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative infections, and an increased susceptibility to STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and HIV.12-15 The risk for vaginal-cuff cellulitis and abscess after hysterectomy is increased 6-fold in the setting of BV.16

Continue to: Clinical manifestations...

Clinical manifestations

BV is characterized by a milky, homogenous, and malodorous vaginal discharge accompanied by vulvovaginal discomfort and vulvar irritation. Vaginal inflammation typically is absent. The associated odor is fishy, and this odor is accentuated when potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added to the vaginal discharge (amine or “whiff” test) or after the patient has coitus. The distinctive odor is due to the release of organic acids and polyamines that are byproducts of anaerobic bacterial metabolism of putrescine and cadaverine. This release is enhanced by exposure of vaginal secretions to alkaline substances such as KOH or semen.

Diagnostic tests and criteria. The diagnosis of BV is made using Amsel criteria or Gram stain with Nugent scoring; bacterial culture is not recommended. Amsel criteria include:

- homogenous, thin, white-gray discharge

- >20% clue cells on saline microscopy (FIGURE 2)

- a pH >4.5 of vaginal fluid

- positive KOH whiff test.

For diagnosis, 3 of the 4 Amsel criteria must be present.17 Gram stain with Nugent score typically is used for research purposes. Nugent scoring assigns a value to different bacterial morphotypes on Gram stain of vaginal secretions. A score of 7 to 10 is consistent with BV.18

Oral and topical treatments

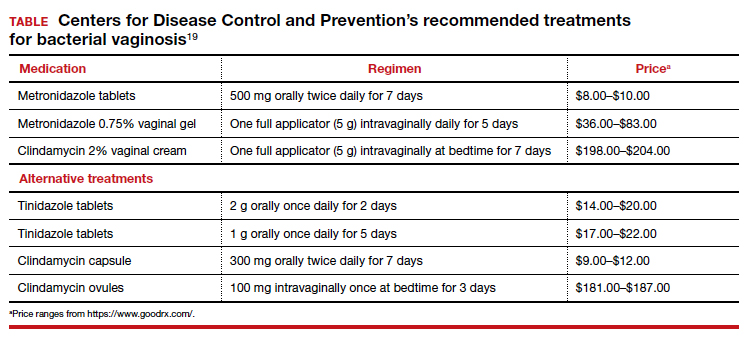

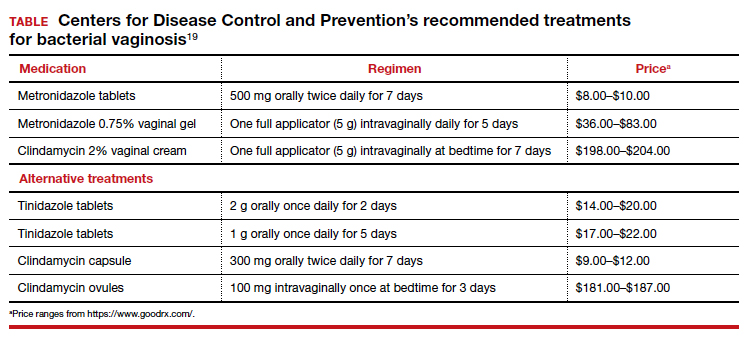

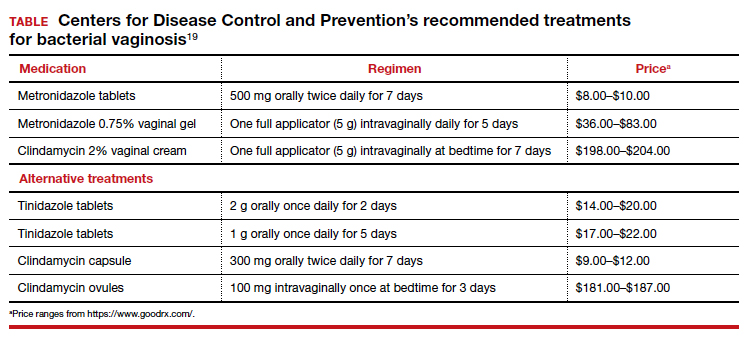

Treatment is recommended for symptomatic patients. Treatment may reduce the risk of transmission and acquisition of other STIs. The TABLE summarizes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for BV treatment,19 with options including both oral and topical regimens. Oral and topical metronidazole and oral and topical clindamycin are equally effective at eradicating the local source of infection20; however, only oral metronidazole and oral clindamycin are effective in preventing the systemic complications of BV. Oral metronidazole has more adverse effects than oral clindamycin—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a disulfiram-like reaction (characterized by flushing, dizziness, throbbing headache, chest and abdominal discomfort, and a distinct hangover effect in addition to nausea and vomiting). However, oral clindamycin can cause antibiotic-associated colitis and is more expensive than metronidazole.

Currently, there are no single-dose regimens for the treatment of BV readily available in the United States. Secnidazole, a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, (17 vs 8 hours) has been used as therapy in Europe and Asia but is not yet available commercially in the United States.21 Hiller and colleagues found that 1 g and 2 g secnidazole oral granules were superior to placebo in treating BV.22 A larger randomized trial comparing this regimen to standard treatment is necessary before this therapy is adopted as the standard of care.

Continue to: Managing recurrent disease...

Managing recurrent disease, a common problem. Bradshaw and colleagues noted that, although the initial treatment of BV is effective in approximately 80% of women, up to 50% have a recurrence within 12 months.23 Data are limited regarding optimal treatment for recurrent infections; however, most regimens consist of some form of suppressive therapy. One regimen includes one full applicator of metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.24 A second regimen consists of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime for 21 days. Upon completion of boric acid therapy, metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% should be administered twice weekly for 6 months.25 A third option is oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 250 mg once every month.26 Of note, boric acid can be fatal if consumed orally and is not recommended during pregnancy.

Most recently, a randomized trial evaluated the ability of L crispatus to prevent BV recurrence. After completion of standard treatment therapy with metronidazole, women were randomly assigned to receive vaginally administered L crispatus (152 patients) or placebo (76 patients) for 11 weeks. In the intention-to-treat population, recurrent BV occurred in 30% of patients in the L crispatus group and 45% of patients in the placebo group. The use of L crispatus significantly reduced recurrence of BV by one-third (P = .01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.87).27 These findings are encouraging; however, confirmatory studies are needed before adopting this as standard of care.

Should sexual partners be treated as well? BV has not traditionally been considered an STI, and the CDC does not currently recommend treatment of partners of women who have BV. However, in women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance is high, and in women who have sex with men, coitus can clearly influence disease activity. Therefore, in patients with refractory BV, we recommend treatment of the sexual partner(s) with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For women having sex with men, we also recommend consistent use of condoms, at least until the patient’s infection is better controlled.28

CASE Resolved

The patient’s clinical findings are indicative of BV. This condition is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery and intrapartum and postpartum infection. To reduce the risk of these systemic complications, she was treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Within 1 week of completing treatment, she noted complete resolution of the malodorous discharge. ●

- Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:451-463.

- Mitchell C, Fredricks D, Agnew K, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli are associated with lower levels of vaginal interleukin-1β, independent of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;42:358-363.

- Munzy CA, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, et al. Identification of key bacteria involved in the induction of incident bacterial vaginosis: a prospective study. J Infect. 2018;218:966-978.

- Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial vaginosis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2246-2254.

- Hardy L, Jespers V, Dahchour N, et al. Unravelling the bacterial vaginosis-associated biofilm: a multiplex Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes. PloS One. 2015;10:E0136658.

- Allswoth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 national health and nutrition examination survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114-120.

- Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:505-523.

- Brookheart RT, Lewis WG, Peipert JF, et al. Association between obesity and bacterial vaginosis as assessed by Nugent score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:476.e1-476.e11.

- Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML, Fichorova RN. The human microbiome during bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:223-238.

- Brown RG, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018;16:9.

- Watts DH, Eschenbach DA, Kenny GE. Early postpartum endometritis: the role of bacteria, genital mycoplasmas, and chlamydia trachomatis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:52-60.

- Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Rabe LK, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of Trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV1-negative women. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:123-128.

- Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, et al. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319-325.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663-668.

- Myer L, Denny L, Telerant R, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect. 2005;192:1372-1380.

- Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1061-1121.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22.

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

- Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm.

- Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006055.

- Videau D, Niel G, Siboulet A, et al. Secnidazole. a 5-nitroimidazole derivative with a long half-life. Br J Vener Dis. 1978;54:77-80.

- Hillier SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect. 2006;193:1478-1486.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:732-734.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect. 2008;197:1361-1368.

- Cohen CR, Wierzbicki MR, French AL, et al. Randomized trial of lactin-v to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:906-915.

- Barbieri RL. Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis. OBG Manag. 2017;29:7-12.

CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.

The vaginal microbiome is polymicrobial and has been classified into at least 5 community state types (CSTs). Four CSTs are dominated by lactobacilli. A fifth CST is characterized by the absence of lactobacilli and high concentrations of obligate or facultative anaerobes.1 The hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli predominate in normal vaginal flora and make up 70% to 90% of the total microbiome. These hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are associated with reduced vaginal proinflammatory cytokines and a highly acidic vaginal pH. Both factors defend against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2

BV is a polymicrobial disorder marked by the significant reduction in the number of vaginal lactobacilli (FIGURE 1). A recent study showed that BV is associated first with a decrease in Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.3 The polymicrobial load is increased by a factor of up to 1,000, compared with normal vaginal flora.4 BV should be considered a biofilm infection caused by adherence of G vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium.5 This biofilm creates a favorable environment for the overgrowth of obligate anaerobic bacteria.

BMI factors into epidemiology

BV is the leading cause of vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated a prevalence of 29% in the general population and 50% in Black women aged 14 to 49 years.6 In 2013, Kenyon and colleagues performed a systematic review to assess the worldwide epidemiology of BV, and the prevalence varied by country. Within the US population, rates were highest among non-Hispanic, Black women.7 Brookheart and colleagues demonstrated that, even after controlling for race, overweight and obese women had a higher frequency of BV compared with leaner women. In this investigation, the overall prevalence of BV was 28.1%. When categorized by body mass index (BMI), the prevalence was 21.3% in lean women, 30.4% in overweight women, and 34.5% in obese women (P<.001). The authors also found that Black women had a higher prevalence, independent of BMI, compared with White women.8

Complications may occur. BV is notable for having several serious sequelae in both pregnant and nonpregnant women. For obstetric patients, these sequelae include an increased risk of preterm birth; first trimester spontaneous abortion, particularly in the setting of in vitro fertilization; intra-amniotic infection; and endometritis.9,10 The risk of preterm birth increases by a factor of 2 in infected women; however, most women with BV do not deliver preterm.4 The risk of endometritis is increased 6-fold in women with BV.11 Nonpregnant women with BV are at increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative infections, and an increased susceptibility to STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and HIV.12-15 The risk for vaginal-cuff cellulitis and abscess after hysterectomy is increased 6-fold in the setting of BV.16

Continue to: Clinical manifestations...

Clinical manifestations

BV is characterized by a milky, homogenous, and malodorous vaginal discharge accompanied by vulvovaginal discomfort and vulvar irritation. Vaginal inflammation typically is absent. The associated odor is fishy, and this odor is accentuated when potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added to the vaginal discharge (amine or “whiff” test) or after the patient has coitus. The distinctive odor is due to the release of organic acids and polyamines that are byproducts of anaerobic bacterial metabolism of putrescine and cadaverine. This release is enhanced by exposure of vaginal secretions to alkaline substances such as KOH or semen.

Diagnostic tests and criteria. The diagnosis of BV is made using Amsel criteria or Gram stain with Nugent scoring; bacterial culture is not recommended. Amsel criteria include:

- homogenous, thin, white-gray discharge

- >20% clue cells on saline microscopy (FIGURE 2)

- a pH >4.5 of vaginal fluid

- positive KOH whiff test.

For diagnosis, 3 of the 4 Amsel criteria must be present.17 Gram stain with Nugent score typically is used for research purposes. Nugent scoring assigns a value to different bacterial morphotypes on Gram stain of vaginal secretions. A score of 7 to 10 is consistent with BV.18

Oral and topical treatments

Treatment is recommended for symptomatic patients. Treatment may reduce the risk of transmission and acquisition of other STIs. The TABLE summarizes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for BV treatment,19 with options including both oral and topical regimens. Oral and topical metronidazole and oral and topical clindamycin are equally effective at eradicating the local source of infection20; however, only oral metronidazole and oral clindamycin are effective in preventing the systemic complications of BV. Oral metronidazole has more adverse effects than oral clindamycin—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a disulfiram-like reaction (characterized by flushing, dizziness, throbbing headache, chest and abdominal discomfort, and a distinct hangover effect in addition to nausea and vomiting). However, oral clindamycin can cause antibiotic-associated colitis and is more expensive than metronidazole.

Currently, there are no single-dose regimens for the treatment of BV readily available in the United States. Secnidazole, a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, (17 vs 8 hours) has been used as therapy in Europe and Asia but is not yet available commercially in the United States.21 Hiller and colleagues found that 1 g and 2 g secnidazole oral granules were superior to placebo in treating BV.22 A larger randomized trial comparing this regimen to standard treatment is necessary before this therapy is adopted as the standard of care.

Continue to: Managing recurrent disease...

Managing recurrent disease, a common problem. Bradshaw and colleagues noted that, although the initial treatment of BV is effective in approximately 80% of women, up to 50% have a recurrence within 12 months.23 Data are limited regarding optimal treatment for recurrent infections; however, most regimens consist of some form of suppressive therapy. One regimen includes one full applicator of metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.24 A second regimen consists of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime for 21 days. Upon completion of boric acid therapy, metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% should be administered twice weekly for 6 months.25 A third option is oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 250 mg once every month.26 Of note, boric acid can be fatal if consumed orally and is not recommended during pregnancy.

Most recently, a randomized trial evaluated the ability of L crispatus to prevent BV recurrence. After completion of standard treatment therapy with metronidazole, women were randomly assigned to receive vaginally administered L crispatus (152 patients) or placebo (76 patients) for 11 weeks. In the intention-to-treat population, recurrent BV occurred in 30% of patients in the L crispatus group and 45% of patients in the placebo group. The use of L crispatus significantly reduced recurrence of BV by one-third (P = .01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.87).27 These findings are encouraging; however, confirmatory studies are needed before adopting this as standard of care.

Should sexual partners be treated as well? BV has not traditionally been considered an STI, and the CDC does not currently recommend treatment of partners of women who have BV. However, in women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance is high, and in women who have sex with men, coitus can clearly influence disease activity. Therefore, in patients with refractory BV, we recommend treatment of the sexual partner(s) with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For women having sex with men, we also recommend consistent use of condoms, at least until the patient’s infection is better controlled.28

CASE Resolved

The patient’s clinical findings are indicative of BV. This condition is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery and intrapartum and postpartum infection. To reduce the risk of these systemic complications, she was treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Within 1 week of completing treatment, she noted complete resolution of the malodorous discharge. ●

CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.

The vaginal microbiome is polymicrobial and has been classified into at least 5 community state types (CSTs). Four CSTs are dominated by lactobacilli. A fifth CST is characterized by the absence of lactobacilli and high concentrations of obligate or facultative anaerobes.1 The hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli predominate in normal vaginal flora and make up 70% to 90% of the total microbiome. These hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are associated with reduced vaginal proinflammatory cytokines and a highly acidic vaginal pH. Both factors defend against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2

BV is a polymicrobial disorder marked by the significant reduction in the number of vaginal lactobacilli (FIGURE 1). A recent study showed that BV is associated first with a decrease in Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.3 The polymicrobial load is increased by a factor of up to 1,000, compared with normal vaginal flora.4 BV should be considered a biofilm infection caused by adherence of G vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium.5 This biofilm creates a favorable environment for the overgrowth of obligate anaerobic bacteria.

BMI factors into epidemiology

BV is the leading cause of vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated a prevalence of 29% in the general population and 50% in Black women aged 14 to 49 years.6 In 2013, Kenyon and colleagues performed a systematic review to assess the worldwide epidemiology of BV, and the prevalence varied by country. Within the US population, rates were highest among non-Hispanic, Black women.7 Brookheart and colleagues demonstrated that, even after controlling for race, overweight and obese women had a higher frequency of BV compared with leaner women. In this investigation, the overall prevalence of BV was 28.1%. When categorized by body mass index (BMI), the prevalence was 21.3% in lean women, 30.4% in overweight women, and 34.5% in obese women (P<.001). The authors also found that Black women had a higher prevalence, independent of BMI, compared with White women.8

Complications may occur. BV is notable for having several serious sequelae in both pregnant and nonpregnant women. For obstetric patients, these sequelae include an increased risk of preterm birth; first trimester spontaneous abortion, particularly in the setting of in vitro fertilization; intra-amniotic infection; and endometritis.9,10 The risk of preterm birth increases by a factor of 2 in infected women; however, most women with BV do not deliver preterm.4 The risk of endometritis is increased 6-fold in women with BV.11 Nonpregnant women with BV are at increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative infections, and an increased susceptibility to STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and HIV.12-15 The risk for vaginal-cuff cellulitis and abscess after hysterectomy is increased 6-fold in the setting of BV.16

Continue to: Clinical manifestations...

Clinical manifestations

BV is characterized by a milky, homogenous, and malodorous vaginal discharge accompanied by vulvovaginal discomfort and vulvar irritation. Vaginal inflammation typically is absent. The associated odor is fishy, and this odor is accentuated when potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added to the vaginal discharge (amine or “whiff” test) or after the patient has coitus. The distinctive odor is due to the release of organic acids and polyamines that are byproducts of anaerobic bacterial metabolism of putrescine and cadaverine. This release is enhanced by exposure of vaginal secretions to alkaline substances such as KOH or semen.

Diagnostic tests and criteria. The diagnosis of BV is made using Amsel criteria or Gram stain with Nugent scoring; bacterial culture is not recommended. Amsel criteria include:

- homogenous, thin, white-gray discharge

- >20% clue cells on saline microscopy (FIGURE 2)

- a pH >4.5 of vaginal fluid

- positive KOH whiff test.

For diagnosis, 3 of the 4 Amsel criteria must be present.17 Gram stain with Nugent score typically is used for research purposes. Nugent scoring assigns a value to different bacterial morphotypes on Gram stain of vaginal secretions. A score of 7 to 10 is consistent with BV.18

Oral and topical treatments

Treatment is recommended for symptomatic patients. Treatment may reduce the risk of transmission and acquisition of other STIs. The TABLE summarizes Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for BV treatment,19 with options including both oral and topical regimens. Oral and topical metronidazole and oral and topical clindamycin are equally effective at eradicating the local source of infection20; however, only oral metronidazole and oral clindamycin are effective in preventing the systemic complications of BV. Oral metronidazole has more adverse effects than oral clindamycin—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and a disulfiram-like reaction (characterized by flushing, dizziness, throbbing headache, chest and abdominal discomfort, and a distinct hangover effect in addition to nausea and vomiting). However, oral clindamycin can cause antibiotic-associated colitis and is more expensive than metronidazole.

Currently, there are no single-dose regimens for the treatment of BV readily available in the United States. Secnidazole, a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, (17 vs 8 hours) has been used as therapy in Europe and Asia but is not yet available commercially in the United States.21 Hiller and colleagues found that 1 g and 2 g secnidazole oral granules were superior to placebo in treating BV.22 A larger randomized trial comparing this regimen to standard treatment is necessary before this therapy is adopted as the standard of care.

Continue to: Managing recurrent disease...

Managing recurrent disease, a common problem. Bradshaw and colleagues noted that, although the initial treatment of BV is effective in approximately 80% of women, up to 50% have a recurrence within 12 months.23 Data are limited regarding optimal treatment for recurrent infections; however, most regimens consist of some form of suppressive therapy. One regimen includes one full applicator of metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.24 A second regimen consists of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime for 21 days. Upon completion of boric acid therapy, metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% should be administered twice weekly for 6 months.25 A third option is oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 250 mg once every month.26 Of note, boric acid can be fatal if consumed orally and is not recommended during pregnancy.

Most recently, a randomized trial evaluated the ability of L crispatus to prevent BV recurrence. After completion of standard treatment therapy with metronidazole, women were randomly assigned to receive vaginally administered L crispatus (152 patients) or placebo (76 patients) for 11 weeks. In the intention-to-treat population, recurrent BV occurred in 30% of patients in the L crispatus group and 45% of patients in the placebo group. The use of L crispatus significantly reduced recurrence of BV by one-third (P = .01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.87).27 These findings are encouraging; however, confirmatory studies are needed before adopting this as standard of care.

Should sexual partners be treated as well? BV has not traditionally been considered an STI, and the CDC does not currently recommend treatment of partners of women who have BV. However, in women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance is high, and in women who have sex with men, coitus can clearly influence disease activity. Therefore, in patients with refractory BV, we recommend treatment of the sexual partner(s) with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For women having sex with men, we also recommend consistent use of condoms, at least until the patient’s infection is better controlled.28

CASE Resolved

The patient’s clinical findings are indicative of BV. This condition is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery and intrapartum and postpartum infection. To reduce the risk of these systemic complications, she was treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Within 1 week of completing treatment, she noted complete resolution of the malodorous discharge. ●

- Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:451-463.

- Mitchell C, Fredricks D, Agnew K, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli are associated with lower levels of vaginal interleukin-1β, independent of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;42:358-363.

- Munzy CA, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, et al. Identification of key bacteria involved in the induction of incident bacterial vaginosis: a prospective study. J Infect. 2018;218:966-978.

- Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial vaginosis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2246-2254.

- Hardy L, Jespers V, Dahchour N, et al. Unravelling the bacterial vaginosis-associated biofilm: a multiplex Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes. PloS One. 2015;10:E0136658.

- Allswoth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 national health and nutrition examination survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114-120.

- Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:505-523.

- Brookheart RT, Lewis WG, Peipert JF, et al. Association between obesity and bacterial vaginosis as assessed by Nugent score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:476.e1-476.e11.

- Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML, Fichorova RN. The human microbiome during bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:223-238.

- Brown RG, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018;16:9.

- Watts DH, Eschenbach DA, Kenny GE. Early postpartum endometritis: the role of bacteria, genital mycoplasmas, and chlamydia trachomatis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:52-60.

- Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Rabe LK, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of Trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV1-negative women. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:123-128.

- Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, et al. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319-325.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663-668.

- Myer L, Denny L, Telerant R, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect. 2005;192:1372-1380.

- Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1061-1121.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22.

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

- Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm.

- Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006055.

- Videau D, Niel G, Siboulet A, et al. Secnidazole. a 5-nitroimidazole derivative with a long half-life. Br J Vener Dis. 1978;54:77-80.

- Hillier SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect. 2006;193:1478-1486.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:732-734.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect. 2008;197:1361-1368.

- Cohen CR, Wierzbicki MR, French AL, et al. Randomized trial of lactin-v to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:906-915.

- Barbieri RL. Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis. OBG Manag. 2017;29:7-12.

- Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:451-463.

- Mitchell C, Fredricks D, Agnew K, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli are associated with lower levels of vaginal interleukin-1β, independent of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;42:358-363.

- Munzy CA, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, et al. Identification of key bacteria involved in the induction of incident bacterial vaginosis: a prospective study. J Infect. 2018;218:966-978.

- Paavonen J, Brunham RC. Bacterial vaginosis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2246-2254.

- Hardy L, Jespers V, Dahchour N, et al. Unravelling the bacterial vaginosis-associated biofilm: a multiplex Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes. PloS One. 2015;10:E0136658.

- Allswoth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 national health and nutrition examination survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114-120.

- Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:505-523.

- Brookheart RT, Lewis WG, Peipert JF, et al. Association between obesity and bacterial vaginosis as assessed by Nugent score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:476.e1-476.e11.

- Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML, Fichorova RN. The human microbiome during bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:223-238.

- Brown RG, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018;16:9.

- Watts DH, Eschenbach DA, Kenny GE. Early postpartum endometritis: the role of bacteria, genital mycoplasmas, and chlamydia trachomatis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:52-60.

- Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Rabe LK, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of Trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV1-negative women. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:123-128.

- Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, et al. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319-325.

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663-668.

- Myer L, Denny L, Telerant R, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect. 2005;192:1372-1380.

- Soper DE, Bump RC, Hurt WG. Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1061-1121.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22.

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

- Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm.

- Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006055.

- Videau D, Niel G, Siboulet A, et al. Secnidazole. a 5-nitroimidazole derivative with a long half-life. Br J Vener Dis. 1978;54:77-80.

- Hillier SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect. 2006;193:1478-1486.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:732-734.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect. 2008;197:1361-1368.

- Cohen CR, Wierzbicki MR, French AL, et al. Randomized trial of lactin-v to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:906-915.

- Barbieri RL. Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis. OBG Manag. 2017;29:7-12.

Syphilis: Cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening

CASE Pregnant woman with positive Treponema pallidum antibody test

A 30-year-old primigravida at 10 weeks and 4 days of gestation by her last menstrual period presents to your office for her initial prenatal visit. She expresses no concerns. You order the standard set of laboratory tests, including a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening panel. Consistent with your institution’s use of the reverse algorithm for syphilis screening, you obtain a Treponema pallidum antibody test, which reflexes to the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Three days later, you receive a notification that this patient’s T pallidum antibody result was positive, followed by negative RPR test results. The follow-up T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test also was negative. Given these findings, you consider:

- What is the correct interpretation of the patient’s sequence of test results?

- Is she infected, and does she require treatment?

Meet our perpetrator

Syphilis has plagued society since the late 15th century, although its causative agent, the spirochete T pallidum, was not recognized until 1905.1,2T pallidum bacteria are transmitted via sexual contact, as well as through vertical transmission during pregnancy or delivery. Infection with syphilis is reported in 50% to 60% of sexual partners after a single exposure to an infected individual with early syphilis, and the mean incubation period is 21 days.3T pallidum can cross the placenta and infect a fetus as early as the sixth week of gestation.3 Congenital syphilis infections occur in the neonates of 50% to 80% of women with untreated primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis infections; maternal syphilis is associated with a 21% increased risk of stillbirth, a 6% increased risk of preterm delivery, and a 9% increased risk of neonatal death.4,5 Additionally, syphilis infection is associated with a high risk of HIV infection, as well as coinfection with other STIs.1

Given the highly infective nature of T pallidum, as well as the severity of the potential consequences of infection for both mothers and babies, primary prevention, education of at-risk populations, and early recognition of clinical features of syphilis infection are of utmost importance in preventing morbidity and mortality. In this article, we review the epidemiology and extensive clinical manifestations of syphilis, as well as current screening recommendations and treatment for pregnant women.

The extent of the problem today

Although US rates of syphilis have ebbed and flowed for the past several decades, the current incidence has grown exponentially in recent years, with the number of cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) increasing by 71% from 2014 to 2018.6 During this time period, reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in women more than doubled (172.7% and 165.4%, respectively) according to CDC data, accompanied by a parallel rise in reported cases of congenital syphilis in both live and stillborn infants.6 In 2018, the CDC reported a national rate of congenital syphilis of 33.1 cases per 100,000 live births, a 39.7% rise compared with data from 2017.6

Those most at risk. Risk factors for syphilis infection include age younger than 30 years, low socioeconomic status, substance abuse, HIV infection, concurrent STIs, and high-risk sexual activity (sex with multiple high-risk partners).3 Additionally, reported rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections, as well as congenital syphilis infections, are more elevated among women who identify as Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Hispanic.6 Congenital infections in the United States are correlated with a lack of prenatal care, which has been similarly linked with racial and socioeconomic disparities, as well as with untreated mental health and substance use disorders and recent immigration to the United States.5,7

Continue to: The many phases of syphilis...

The many phases of syphilis

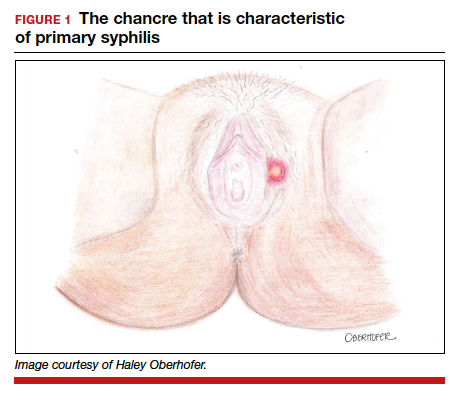

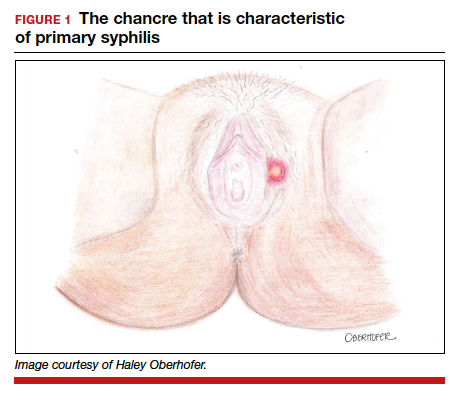

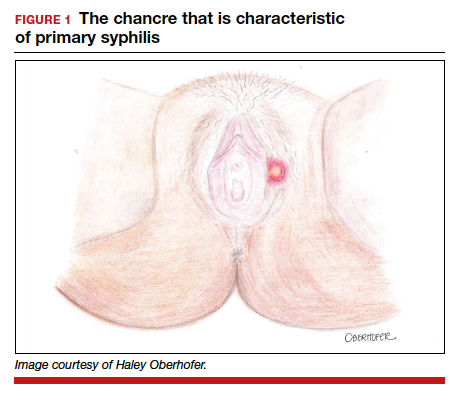

The characteristic lesion of primary syphilis is a chancre, which is a painless, ulcerative lesion with raised borders and a clean, indurated base appearing at the site of spirochete entry (FIGURE 1). Chancres most commonly appear in the genital area, with the most frequent sites in females being within the vaginal canal or on the cervix. Primary chancres tend to heal spontaneously within 3 to 6 weeks, even without treatment, and frequently are accompanied by painless inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given that the most common chancre sites are not immediately apparent, primary infections in women often go undetected.3 In fact, it is essential for clinicians to recognize that, in our routine practice, most patients with syphilis will not be symptomatic at all, and the diagnosis will only be made by serologic screening.

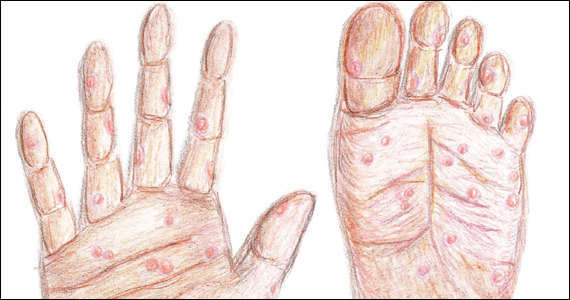

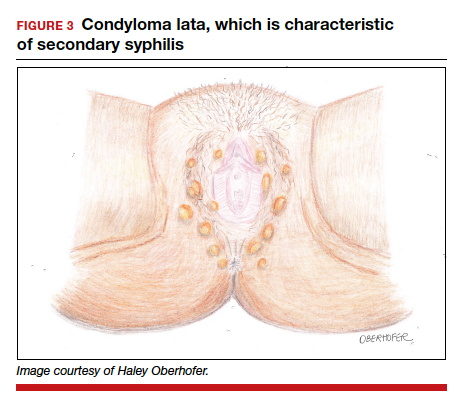

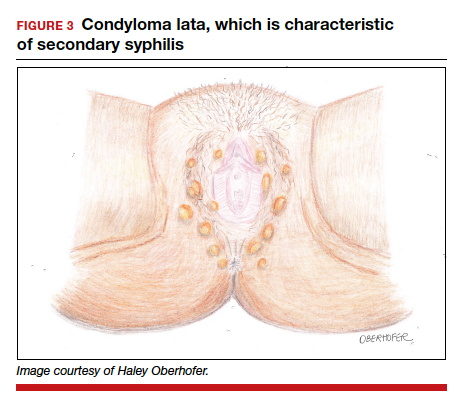

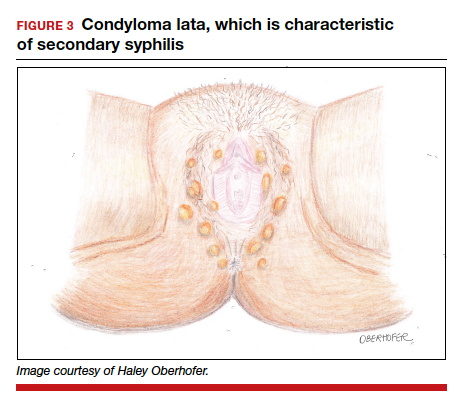

Following resolution of the primary phase, the patient may enter the secondary stage of T pallidum infection. During this stage, spirochetes may disseminate throughout the bloodstream to infect all major organ systems. The principal manifestations of secondary syphilis include a diffuse maculopapular rash that begins on the trunk and proximal extremities and spreads to include the palms and soles (FIGURE 2); mucosal lesions, such as mucous patches and condyloma lata (FIGURE 3); nonscarring alopecia; periostitis; generalized lymphadenopathy; and, in some cases, hepatitis or nephritis.1,3

Secondary syphilis usually clears within 2 to 6 weeks, with the patient then entering the early latent stage of syphilis. During this period, up to 25% of patients are subject to flares of secondary syphilitic lesions but otherwise are asymptomatic.1,3,4 These recurrences tend to occur within 1 year, hence the distinction between early and late latent stages. Once a year has passed, patients are not contagious by sexual transmission and are unlikely to suffer a relapse of secondary symptoms.1,3 However, late latent syphilis is characterized by periods of intermittent bacteremia that allow for seeding of the placenta and infection in about 10% of fetuses.5

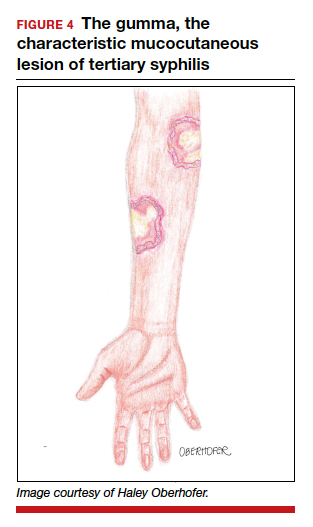

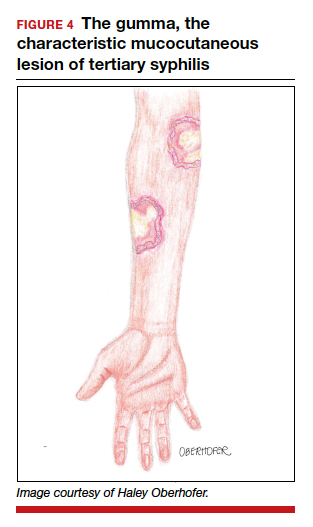

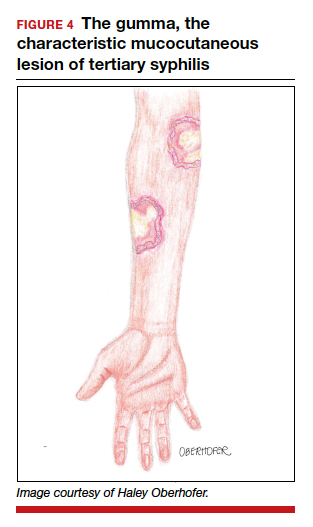

Untreated, about 40% of patients will progress to the tertiary stage of syphilis, which is characterized by gummas affecting the skin and mucous membranes (FIGURE 4) and cardiovascular manifestations including arterial aneurysms and aortic insufficiency.3

Neurologic manifestations of syphilis may arise during any of the above stages, though the most characteristic manifestations tend to appear decades after the primary infection. Early neurosyphilis may present as meningitis, with or without concomitant ocular syphilis (uveitis, retinitis) and/or as otic syphilis (hearing loss, persistent tinnitus).1,5 Patients with late (tertiary) neurosyphilis tend to exhibit meningovascular symptoms similar to stroke (aphasia, hemiplegia, seizures) and/or parenchymal effects such as general paresis. Tabes dorsalis (manifestations of which include urinary and rectal incontinence, lightning pains, and ataxia) is a late-onset manifestation.1,3

Congenital syphilis can be subdivided into an early and late stage. The first stage, in which clinical findings occur within the first 2 years of life, commonly features a desquamating rash, hepatomegaly, and rhinitis. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, periostitis, and osteomyelitis also have been documented.5 Of note, two-thirds of infants are asymptomatic at birth and may not develop such clinical manifestations for 3 to 8 weeks.3 If untreated, early congenital infection may progress to late manifestations, such as Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, interstitial keratitis, deafness, saddle nose, saber shins, and such neurologic abnormalities as developmental delay and general paresis.3

Continue to: Prenatal screening and diagnosis...

Prenatal screening and diagnosis

Current recommendations issued by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that all pregnant women should be screened for syphilis infection at their first presentation to care, with repeat screening between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation and at birth, for women living in areas with a high prevalence of syphilis and/or with any of the aforementioned risk factors.3,5 Given that providers may be unfamiliar with the prevalence of syphilis in their area, and that patients may acquire or develop an infection later on in their pregnancy, researchers have begun to investigate the feasibility of universal third-trimester screening. While the cost-effectiveness of such a protocol is disputed, recent studies suggest that it may result in a substantial decrease in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.8,9

Diagnostic tests

The traditional algorithm for the diagnosis of syphilis infection begins with a nontreponemal screening test, such as the RPR or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. If positive, these screening tests are followed by a confirmatory treponemal test, such as the

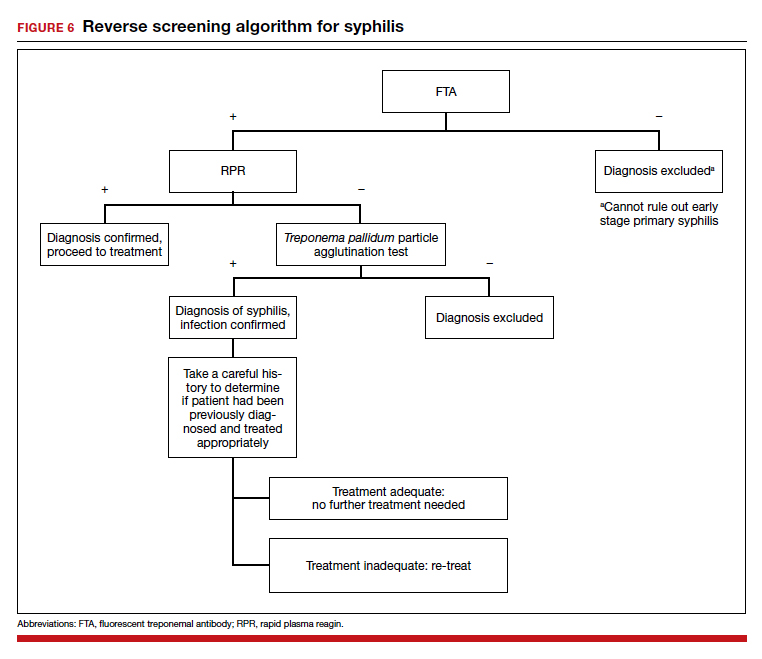

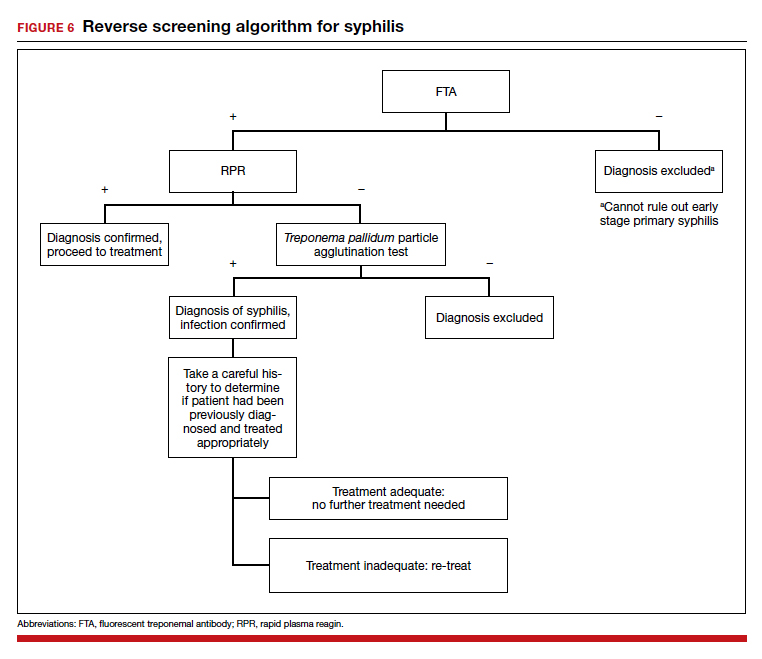

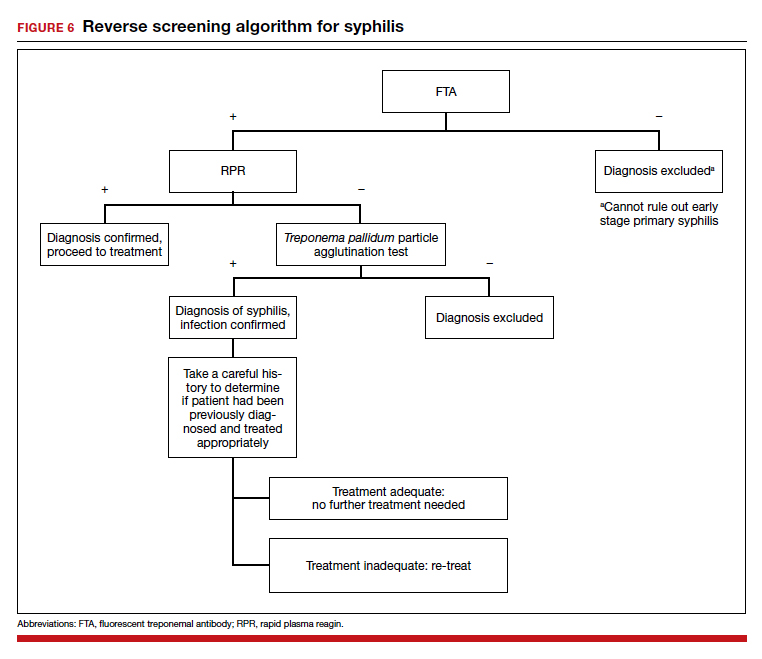

The “reverse” screening algorithm begins with the FTA and, if positive, reflexes to the RPR. A reactive RPR indicates an active infection, and the patient should be treated. A negative RPR should be followed by the TP-PA to rule out a false-positive immunoglobulin G test. If the TP-PA test result is positive, the diagnosis of syphilis is confirmed (FIGURE 6). It is crucial to understand, however, that treponemal antibodies will remain positive for a patient’s lifetime, and someone who may have been treated for syphilis in the past also will screen positive. Once 2 treponemal tests are positive, physicians should take a careful history to assess prior infection risk and treatment status. A negative TP-PA excludes a diagnosis of syphilis.

Advantages of the reverse screening algorithm. Nontreponemal tests are inexpensive and easy to perform, and titers allow for identification of a baseline to evaluate response to treatment.11 However, given the fluctuation of RPR sensitivity (depending on stage of disease and a decreased ability to detect primary and latent stages of syphilis), there has been a resurgence of interest in the reverse algorithm.11 While reverse screening has been found to incur higher costs, and may result in overtreatment and increased stress due to false-positive results,12 there is evidence to suggest that this algorithm is more sensitive for primary and latent infections.8,11,13-15

Given the rise in prevalence of syphilis infections in the United States over the past decade, and therefore a higher pretest probability of syphilis in the population, we favor the reverse screening algorithm in obstetrics, particularly given the risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

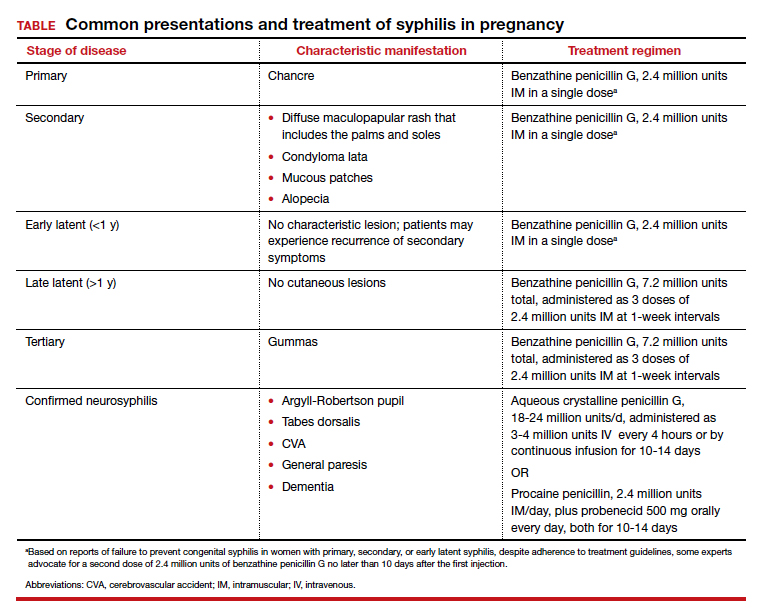

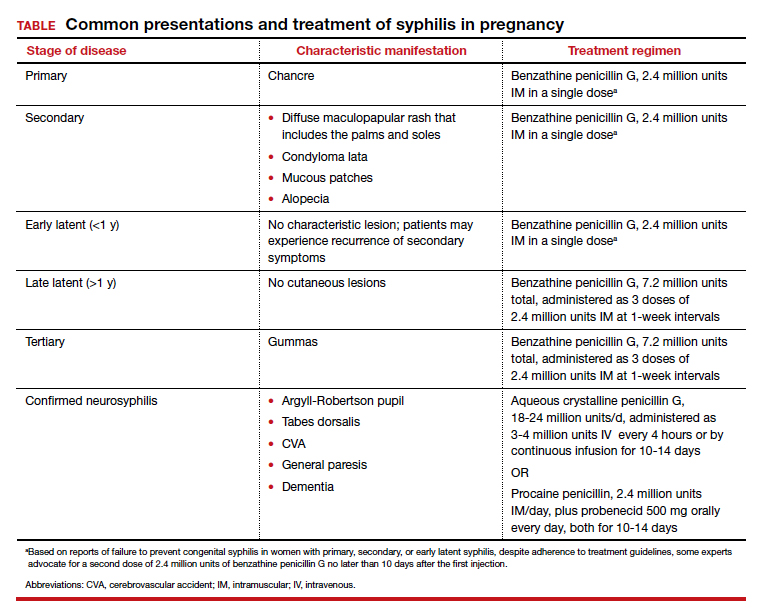

Treating syphilis in pregnancy

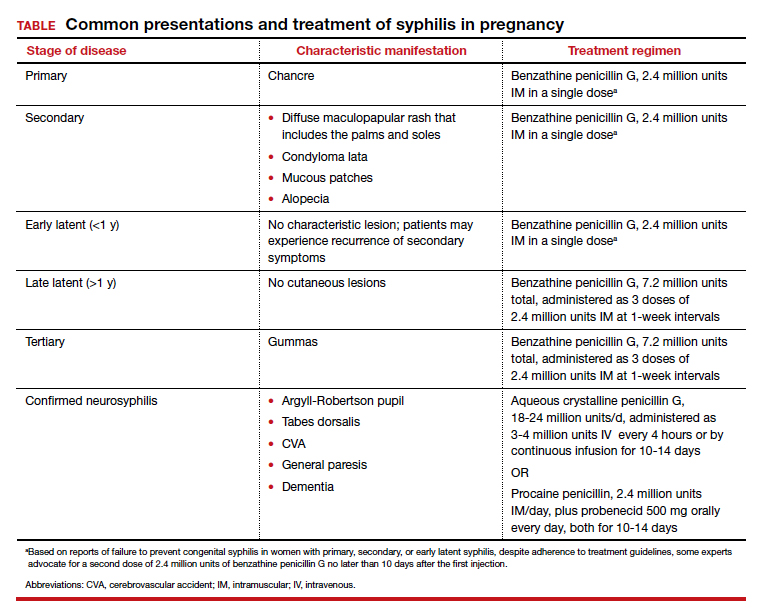

Parenteral benzathine penicillin G is the only currently recommended medication for the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy. This drug is effective in treating maternal infection and in preventing fetal infections, as well as in treating established fetal infections.3,5 Regimens differ depending on the stage of syphilis infection (TABLE). Treatment for presumed early syphilis is recommended for women who have had sexual contact with a partner diagnosed with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis within 3 months of their current pregnancy.5 Any patient with diagnosed syphilis who demonstrates clinical signs of neurologic involvement should undergo lumbar puncture to assess for evidence of neurosyphilis.3 CDC guidelines recommend that patients who report an allergy to penicillin undergo desensitization therapy in a controlled setting, as other antibiotics that have been investigated in the treatment of syphilis are either not appropriate due to teratogenicity or due to suboptimal fetal treatment.3,5

Syphilotherapy may lead to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which is an acute systemic reaction to inflammatory cytokines produced in response to lipopolysaccharide released by dying spirochetes.5 This reaction is characterized by fever, chills, myalgia, headache, hypotension, and worsening of cutaneous lesions. Preterm labor and delivery and fetal heart rate tracing abnormalities also have been documented in pregnant women experiencing this reaction, particularly during the second half of pregnancy.16 Prior to the start of treatment, a detailed sonographic assessment should be performed to assess the fetus for signs of early syphilis, including hepatomegaly, elevated peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery (indicative of fetal anemia), polyhydramnios, placentomegaly, or hydrops.5,7

CASE Resolved

The combination of the patient’s test results—positive FTA, negative RPR, and negative TP-PA—suggest a false-positive treponemal assay. This sequence of tests excludes a diagnosis of syphilis; therefore, no treatment is necessary. Depending on the prevalence of syphilis in the patient’s geographic location, as well as her sexual history, rescreening between 28 and 32 weeks may be warranted. ●

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Barnett R. Syphilis. Lancet. 2018;391:1471.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore T, et al. Creasy and Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:862-919.

- Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, et al. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:217-226.

- Adhikari EH. Syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1121-1135.

- Syphilis. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/syphilis.htm. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Rac MF, Revell PA, Eppes CS. Syphilis during pregnancy: a preventable threat to maternal-fetal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;4:352-363.

- Dunseth CD, Ford BA, Krasowski MD. Traditional versus reverse syphilis algorithms: a comparison at a large academic medical center. Pract Lab Med. 2017;8:52-59.

- Hersh AR, Megli CJ, Caughey AB. Repeat screening for syphilis in the third trimester of pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:699-706.

- Albright CM, Emerson JB, Werner EF, et al. Third trimester prenatal syphilis screening: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:479-485.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Peterman TA, Ballard RC. Serologic testing for syphilis in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis of two screening algorithms. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:1-7.

- Huh HJ, Chung JW, Park SY, et al. Comparison of automated treponemal and nontreponemal test algorithms as first-line syphilis screening assays. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36:23-27.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal test for initial screening-four laboratories. New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:872-875.

- Mishra S, Boily MC, Ng V, et al. The laboratory impact of changing syphilis screening from the rapid-plasma reagin to a treponemal enzyme immunoassay: a case-study from the greater Toronto area. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:190-196.

- Klein VR, Cox SM, Mitchell MD, et al. The Jarisch-Herzheimer reaction complicating syphilotherapy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:375-380.

CASE Pregnant woman with positive Treponema pallidum antibody test

A 30-year-old primigravida at 10 weeks and 4 days of gestation by her last menstrual period presents to your office for her initial prenatal visit. She expresses no concerns. You order the standard set of laboratory tests, including a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening panel. Consistent with your institution’s use of the reverse algorithm for syphilis screening, you obtain a Treponema pallidum antibody test, which reflexes to the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Three days later, you receive a notification that this patient’s T pallidum antibody result was positive, followed by negative RPR test results. The follow-up T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test also was negative. Given these findings, you consider:

- What is the correct interpretation of the patient’s sequence of test results?

- Is she infected, and does she require treatment?

Meet our perpetrator

Syphilis has plagued society since the late 15th century, although its causative agent, the spirochete T pallidum, was not recognized until 1905.1,2T pallidum bacteria are transmitted via sexual contact, as well as through vertical transmission during pregnancy or delivery. Infection with syphilis is reported in 50% to 60% of sexual partners after a single exposure to an infected individual with early syphilis, and the mean incubation period is 21 days.3T pallidum can cross the placenta and infect a fetus as early as the sixth week of gestation.3 Congenital syphilis infections occur in the neonates of 50% to 80% of women with untreated primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis infections; maternal syphilis is associated with a 21% increased risk of stillbirth, a 6% increased risk of preterm delivery, and a 9% increased risk of neonatal death.4,5 Additionally, syphilis infection is associated with a high risk of HIV infection, as well as coinfection with other STIs.1

Given the highly infective nature of T pallidum, as well as the severity of the potential consequences of infection for both mothers and babies, primary prevention, education of at-risk populations, and early recognition of clinical features of syphilis infection are of utmost importance in preventing morbidity and mortality. In this article, we review the epidemiology and extensive clinical manifestations of syphilis, as well as current screening recommendations and treatment for pregnant women.

The extent of the problem today

Although US rates of syphilis have ebbed and flowed for the past several decades, the current incidence has grown exponentially in recent years, with the number of cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) increasing by 71% from 2014 to 2018.6 During this time period, reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in women more than doubled (172.7% and 165.4%, respectively) according to CDC data, accompanied by a parallel rise in reported cases of congenital syphilis in both live and stillborn infants.6 In 2018, the CDC reported a national rate of congenital syphilis of 33.1 cases per 100,000 live births, a 39.7% rise compared with data from 2017.6

Those most at risk. Risk factors for syphilis infection include age younger than 30 years, low socioeconomic status, substance abuse, HIV infection, concurrent STIs, and high-risk sexual activity (sex with multiple high-risk partners).3 Additionally, reported rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections, as well as congenital syphilis infections, are more elevated among women who identify as Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Hispanic.6 Congenital infections in the United States are correlated with a lack of prenatal care, which has been similarly linked with racial and socioeconomic disparities, as well as with untreated mental health and substance use disorders and recent immigration to the United States.5,7

Continue to: The many phases of syphilis...

The many phases of syphilis

The characteristic lesion of primary syphilis is a chancre, which is a painless, ulcerative lesion with raised borders and a clean, indurated base appearing at the site of spirochete entry (FIGURE 1). Chancres most commonly appear in the genital area, with the most frequent sites in females being within the vaginal canal or on the cervix. Primary chancres tend to heal spontaneously within 3 to 6 weeks, even without treatment, and frequently are accompanied by painless inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given that the most common chancre sites are not immediately apparent, primary infections in women often go undetected.3 In fact, it is essential for clinicians to recognize that, in our routine practice, most patients with syphilis will not be symptomatic at all, and the diagnosis will only be made by serologic screening.

Following resolution of the primary phase, the patient may enter the secondary stage of T pallidum infection. During this stage, spirochetes may disseminate throughout the bloodstream to infect all major organ systems. The principal manifestations of secondary syphilis include a diffuse maculopapular rash that begins on the trunk and proximal extremities and spreads to include the palms and soles (FIGURE 2); mucosal lesions, such as mucous patches and condyloma lata (FIGURE 3); nonscarring alopecia; periostitis; generalized lymphadenopathy; and, in some cases, hepatitis or nephritis.1,3

Secondary syphilis usually clears within 2 to 6 weeks, with the patient then entering the early latent stage of syphilis. During this period, up to 25% of patients are subject to flares of secondary syphilitic lesions but otherwise are asymptomatic.1,3,4 These recurrences tend to occur within 1 year, hence the distinction between early and late latent stages. Once a year has passed, patients are not contagious by sexual transmission and are unlikely to suffer a relapse of secondary symptoms.1,3 However, late latent syphilis is characterized by periods of intermittent bacteremia that allow for seeding of the placenta and infection in about 10% of fetuses.5

Untreated, about 40% of patients will progress to the tertiary stage of syphilis, which is characterized by gummas affecting the skin and mucous membranes (FIGURE 4) and cardiovascular manifestations including arterial aneurysms and aortic insufficiency.3

Neurologic manifestations of syphilis may arise during any of the above stages, though the most characteristic manifestations tend to appear decades after the primary infection. Early neurosyphilis may present as meningitis, with or without concomitant ocular syphilis (uveitis, retinitis) and/or as otic syphilis (hearing loss, persistent tinnitus).1,5 Patients with late (tertiary) neurosyphilis tend to exhibit meningovascular symptoms similar to stroke (aphasia, hemiplegia, seizures) and/or parenchymal effects such as general paresis. Tabes dorsalis (manifestations of which include urinary and rectal incontinence, lightning pains, and ataxia) is a late-onset manifestation.1,3

Congenital syphilis can be subdivided into an early and late stage. The first stage, in which clinical findings occur within the first 2 years of life, commonly features a desquamating rash, hepatomegaly, and rhinitis. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, periostitis, and osteomyelitis also have been documented.5 Of note, two-thirds of infants are asymptomatic at birth and may not develop such clinical manifestations for 3 to 8 weeks.3 If untreated, early congenital infection may progress to late manifestations, such as Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, interstitial keratitis, deafness, saddle nose, saber shins, and such neurologic abnormalities as developmental delay and general paresis.3

Continue to: Prenatal screening and diagnosis...

Prenatal screening and diagnosis

Current recommendations issued by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that all pregnant women should be screened for syphilis infection at their first presentation to care, with repeat screening between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation and at birth, for women living in areas with a high prevalence of syphilis and/or with any of the aforementioned risk factors.3,5 Given that providers may be unfamiliar with the prevalence of syphilis in their area, and that patients may acquire or develop an infection later on in their pregnancy, researchers have begun to investigate the feasibility of universal third-trimester screening. While the cost-effectiveness of such a protocol is disputed, recent studies suggest that it may result in a substantial decrease in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.8,9

Diagnostic tests

The traditional algorithm for the diagnosis of syphilis infection begins with a nontreponemal screening test, such as the RPR or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. If positive, these screening tests are followed by a confirmatory treponemal test, such as the

The “reverse” screening algorithm begins with the FTA and, if positive, reflexes to the RPR. A reactive RPR indicates an active infection, and the patient should be treated. A negative RPR should be followed by the TP-PA to rule out a false-positive immunoglobulin G test. If the TP-PA test result is positive, the diagnosis of syphilis is confirmed (FIGURE 6). It is crucial to understand, however, that treponemal antibodies will remain positive for a patient’s lifetime, and someone who may have been treated for syphilis in the past also will screen positive. Once 2 treponemal tests are positive, physicians should take a careful history to assess prior infection risk and treatment status. A negative TP-PA excludes a diagnosis of syphilis.

Advantages of the reverse screening algorithm. Nontreponemal tests are inexpensive and easy to perform, and titers allow for identification of a baseline to evaluate response to treatment.11 However, given the fluctuation of RPR sensitivity (depending on stage of disease and a decreased ability to detect primary and latent stages of syphilis), there has been a resurgence of interest in the reverse algorithm.11 While reverse screening has been found to incur higher costs, and may result in overtreatment and increased stress due to false-positive results,12 there is evidence to suggest that this algorithm is more sensitive for primary and latent infections.8,11,13-15

Given the rise in prevalence of syphilis infections in the United States over the past decade, and therefore a higher pretest probability of syphilis in the population, we favor the reverse screening algorithm in obstetrics, particularly given the risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Treating syphilis in pregnancy