User login

FDA Regulation of Predictive Clinical Decision-Support Tools: What Does It Mean for Hospitals?

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

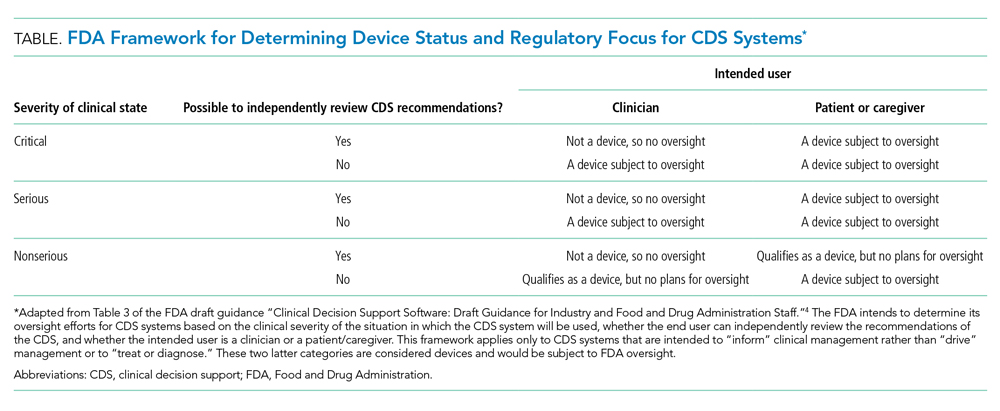

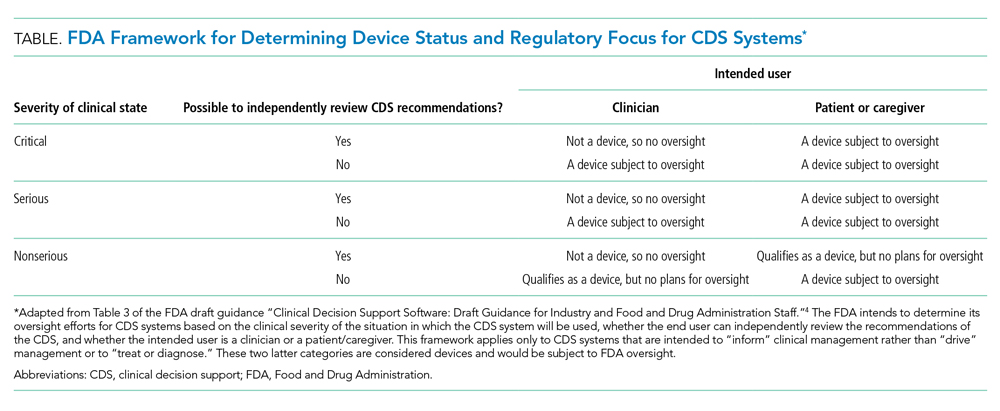

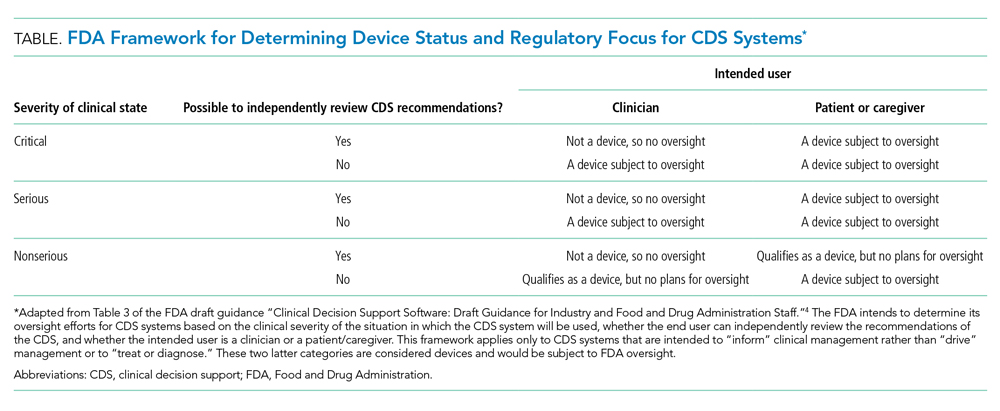

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

Recent experiences in the transportation industry highlight the importance of getting right the regulation of decision-support systems in high-stakes environments. Two tragic plane crashes resulted in 346 deaths and were deemed, in part, to be related to a cockpit alert system that overwhelmed pilots with multiple notifications.1 Similarly, a driverless car struck and killed a pedestrian in the street, in part because the car was not programmed to look for humans outside of a crosswalk.2 These two bellwether events offer poignant lessons for the healthcare industry in which human lives also depend on decision-support systems.

Clinical decision-support (CDS) systems are computerized applications, often embedded in an electronic health record (EHR), that provide information to clinicians to inform care. Although CDS systems have been used for many years,3 they have never been subjected to any enforcement of formal testing requirements. However, a draft guidance document released in 2019 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outlined new directions for the regulation of CDS systems.4 Although the FDA has thus far focused regulatory efforts on predictive systems developed by private manufacturers,5,6 this new document provides examples of software that would require regulation for CDS systems that hospitals are already using. Thus, this new guidance raises critical questions—will hospitals themselves be evaluated like private manufacturers, be exempted from federal regulation, or require their own specialized regulation? The FDA has not yet clarified its approach to hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, which leaves open numerous possibilities in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

Although the FDA has officially regulated CDS systems under section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), only recently has the FDA begun to sketch the shape of its regulatory efforts. This trend to actually regulate CDS systems began with the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) that amended the definition of software systems that qualify as medical devices and outlined criteria under which a system may be exempt from FDA oversight. For example, regulation would not apply to systems that support “population health” or a “healthy lifestyle” or to ones that qualify as “electronic patient records” as long as they do not “interpret or analyze” data within them.7 Following the rapid proliferation of many machine learning and other predictive technologies with medical applications, the FDA began the voluntary Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Program in 2017. Through this program, the FDA selected nine companies from more than 100 applicants and certified them across five domains of excellence. Notably, the Pre-Cert Program currently allows for certification of software manufacturers themselves and does not approve or test actual software devices directly. This regulatory pathway will eventually allow manufacturers to apply under a modified premarket review process for individual software as a medical device (SaMD) that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. In the meantime, however, many hospitals have developed and deployed their own predictive CDS systems that cross the boundaries into the FDA’s purview and, indeed, do “interpret or analyze” data for real-time EHR alerts, population health management, and other applications.

Regulatory oversight for hospitals could provide quality or safety standards where currently there are none. However, such regulations could also interfere with existing local care practices, hinder rapid development of new CDS systems, and may be perceived as interfering in hospital operations. With the current enthusiasm for AI-based technologies and the concurrent lack of evidence to suggest their effectiveness in practice, regulation could also prompt necessary scrutiny of potential harms of CDS systems, an area with even less evidence. At the same time, CDS developers—private or hospital based—may be able to avoid regulation for some devices with well-placed disclaimers about the intended use of the CDS, one of the FDA criteria for determining the degree of oversight. If the FDA were to regulate hospitals or hospital-developed CDS systems, there are several unanswered questions to consider so that such regulations have their intended impact.

First, does the FDA intend to regulate hospitals and hospital-developed software at all? The framework for determining whether a CDS system will be regulated depends on the severity of the clinical scenario, the ability to independently evaluate the model output, and the intended user (Table). Notably, many types of CDS systems that would require regulation under this framework are already commonplace. For example, the FDA intends to regulate software that “identifies patients who may exhibit signs of opioid addiction,” a scenario similar to prediction models already developed at academic hospitals.8 The FDA also plans to regulate a software device even if it is not a CDS system if it is “intended to generate an alarm or an alert to notify a caregiver of a life-threatening condition, such as stroke, and the caregiver relies primarily on this alarm or alert to make a treatment decision.” Although there are no published reports of stroke-specific early warning systems in use, analogous nonspecific and sepsis-specific early warning systems to prompt urgent clinical care have been deployed by hospitals directly9 and developed for embedding in commercial EHRs.10 Hospitals need clarification on the FDA’s regulatory intentions for such CDS systems. FDA regulation of hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems would fill a critical oversight need and potentially strengthen processes to improve safety and effectiveness. But burdensome regulations may also restrain hospitals from tackling complex problems in medicine for which they are uniquely suited.

Such a regulatory environment may be especially prohibitive for safety-net hospitals that could find themselves at a disadvantage in developing their own CDS systems relative to large academic medical centers that are typically endowed with greater resources. Additionally, CDS systems developed at academic medical centers may not generalize well to populations in the community setting, which could further deepen disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies. For example, racial bias in treatment and referral patterns could bias training labels for CDS systems focused on population health management.11 Similarly, the composition of patient skin color in one population may distort predictions of a model in another with a different distribution of skin color, even when the primary outcome of a prediction model is gender.12 Additional regulatory steps may apply for models that are adapted to new populations or recalibrated across locations and time.13 Until there is more data on the clinical impact of such CDS systems, it is unknown how potential differences in evaluation and approval would actually affect clinical outcomes.

Second, would hospitals be eligible for the Pre-Cert program, and if so, would they be held to the same standards as a private technology manufacturer? The domains of excellence required for precertification approval such as “patient safety,” “clinical responsibility,” and “proactive culture” are aligned with the efforts of hospitals that are already overseen and accredited by organizations like the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the American Nurses Credentialing Center. There is limited motivation for the FDA to be in the business of regulating these aspects of hospital functions. However, while domains like “product quality” and “cybersecurity” may be less familiar to some hospitals, these existing credentialing bodies may be better suited than the FDA to set and enforce standards for hospitals. In contrast, private manufacturers may have deep expertise in these latter domains. Therefore, as with public-private partnerships for the development of predictive radiology applications,14 synergies between hospitals and manufacturers may also prove useful for obtaining approvals in a competitive marketplace. Simultaneously, such collaborations would continue to raise questions about conflicts of interest and data privacy.

Finally, regardless of how the FDA will regulate hospitals, what will become of predictive CDS systems that fall outside of the FDA’s scope? Hospitals will continue to find themselves in the position of self-regulation without clear guidance. Although the FDA suggests that developers of unregulated CDS systems still follow best practices for software validation and cybersecurity, existing guidance documents in these domains do not cover the full range of concerns relevant to the development, deployment, and oversight of AI-based CDS systems in the clinical domain. Nor do most hospitals have the infrastructure or expertise to oversee their own CDS systems. Disparate recommendations for development, training, and oversight of AI-based medical systems have emerged but have yet to be endorsed by a federal regulatory body or become part of the hospital accreditation process.15 Optimal local oversight would require a collaboration between clinical experts, hospital operations leaders, statisticians, data scientists, and ethics experts to ensure effectiveness, safety, and fairness.

Hospitals will remain at the forefront of developing and implementing predictive CDS systems. The proposed FDA regulatory framework would mark an important step toward realizing benefit from such systems, but the FDA needs to clarify the requirements for hospitals and hospital-developed CDS systems to ensure reasonable standards that account for their differences from private software manufacturers. Should the FDA choose to focus regulation on private manufacturers only, hospitals leaders may both feel more empowered to develop their own local CDS tools and feel more comfortable buying CDS systems from vendors that have been precertified. This strategy would provide an optimal balance of assurance and flexibility while maintaining quality standards that ultimately improve patient care.

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

1. Sumwalt RL III, Landsbert B, Homendy J. Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf

2. Becic E, Zych N, Ivarsson J. Vehicle Automation Report. National Transportation Safety Board; 2019. https://dms.ntsb.gov/public/62500-62999/62978/629713.pdf

3. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y

4. Clinical Decision Support Software: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download

5. Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17216

6. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

7. Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/109622/download

8. Lo-Ciganic W-H, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

9. Smith MEB, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1454-1465. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201403-102oc

10. WAVE Clinical Platform 510(k) Premarket Notification. Food and Drug Administration. January 4, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K171056

11. Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

12. Buolamwini J, Gebru T. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proc Machine Learning Res. 2018;81:1-15.

13. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Food and Drug Administration. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FDA-2019-N-1185-0001&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

14. Allen B. The role of the FDA in ensuring the safety and efficacy of artificial intelligence software and devices. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(2):208-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.007

15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Multiplying the Impact of Opioid Settlement Funds by Investing in Primary Prevention

There is growing momentum to hold drug manufacturers accountable for the more than 400,000 US opioid overdose deaths that have occurred since 1999.1 As state lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors wind their way through the legal system, hospitals—which may benefit from settlement funds—have been paying close attention. Recently, former Governor John Kasich (R-Ohio), West Virginia University president E. Gordon Gee, and America’s Essential Hospitals argued that adequately compensating hospitals for the costs of being on the crisis’ “front lines” requires prioritizing them as settlement fund recipients.2

Hospitals should be laying the groundwork for how settlement funds might be used. They may consider enhancing some of the most promising, evidence-based services for individuals with opioid use disorders (OUDs), including improving treatment for commonly associated health conditions such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV); expanding ambulatory long-term antibiotic treatment for endocarditis and other intravenous drug use–associated infections; more broadly adopting harm-reduction practices such as naloxone coprescribing; and applying best practices to caring for substance-exposed infants. They could also develop clinical services not already provided, including creating programs for OUD management during pregnancy and initiating medication for OUD in inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory settings. In short, hospitals play a critical role in engaging people with OUD in treatment at every possible opportunity.3

When considering how to most effectively use opioid settlement funding, hospitals may consider adding or expanding these much-needed clinical services to address opioid-related harms; however, their efforts should not stop there. Investments made outside hospital walls could have a significant effect on the public’s health, especially if they target social determinants of health. By tackling factors in the pathway to developing OUD, such as lack of meaningful employment, affordable housing, and mental health care, hospitals can move beyond treating the downstream consequences of addiction and toward preventing community-level opioid-related harms. To accomplish this daunting goal, hospitals will need to strengthen existing relationships with community partners and build new ones. Yet in a 2015 study, only 54% of nonprofit hospitals proposed a strategy to address the overdose crisis that involved community partnering.4

In this Perspective, we describe the following three strategies hospitals can use to multiply the reach of their opioid settlement funding by addressing root causes of opioid use through primary prevention: (1) supporting economic opportunities in their communities, (2) expanding affordable housing options in surrounding neighborhoods, and (3) building capacity in ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent OUD (Table).

SUPPORTING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY IN THEIR COMMUNITIES

Lack of economic opportunity is one of many root causes of opioid use. For example, a recent study found that automotive assembly plant closures were associated with increases in opioid overdose mortality.5 To tackle this complex issue, hospitals can play a crucial role in expanding employment and career advancement options for members of their local communities. Specifically, hospitals can do the following:

- Create jobs within the healthcare system and preferentially recruit and hire from surrounding neighborhoods

- Establish structured career development programs to build skills among entry-level healthcare employees

- Award contracts of varying sizes to locally owned businesses

- Employ individuals with lived experience with substance use disorders, such as peer recovery coaches6

To illustrate how health systems are investing in enhancing career opportunities for members of their communities, hundreds of institutions have implemented “School at Work,” a 6-month career development program for entry-level healthcare employees.7 The hospitals’ Human Resources department trains participants in communication skills, reading and writing, patient safety and satisfaction, medical terminology, and strategies for success and career advancement. Evaluations of this program have demonstrated improved employee outcomes and a favorable return on investment for hospitals.8

As “anchor institutions” and large employers in many communities, hospitals can simultaneously enhance their own workforce and offer employment opportunities that can help break the cycle of addiction that commonly traps individuals and families in communities affected by the overdose crisis.

EXPANDING AFFORDABLE HOUSING OPTIONS

Hospitals are increasingly supporting interventions that fall outside their traditional purview as they seek to improve population health, such as developing safe green outdoor spaces and increasing access to healthy food options by supporting local farmers markets and grocers.9 Stable, decent, and affordable housing is critically important to health and well-being,10 and there is a well-documented association of opioid use disorder and opioid misuse with housing instability.11 Given evidence of improved outcomes with hospital-led housing interventions,12 a growing number of hospitals are partnering with housing authorities and community groups to help do the following13:

- Contribute to supportive housing options

- Provide environmental health assessments, repairs, and renovations

- Buy or develop affordable housing units

Boston Medical Center, where one in four inpatients are experiencing homelessnes and one in three pediatric emergency department patients are housing insecure, provides an example of how a hospital has invested in housing.14 In 2017, the hospital began a 5-year, $6.5 million investment in community partnerships in surrounding neighborhoods. Instead of building housing units or acting as a landlord, the hospital chose to invest funding in creative ways to increase the pool of affordable housing. It invested $1 million to rehabilitate permanent, supportive housing units for individuals with mental health conditions in a nearby Boston neighborhood and in a housing stabilization program for people with complex medical issues including substance use disorder. It provided resources to a homeless shelter near the hospital and to the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, which provides healthcare to individuals with housing instability. It also funded a community wellness advocate based at the hospital, who received training in substance use disorders and served as a liaison between the hospital and the Boston Housing Authority.

Housing instability is just one of the social determinants of health that hospitals have the capacity to address as they consider where to invest their opioid settlement funds.

BUILDING PREVENTION CAPACITY IN THE COMMUNITY

Finally, hospitals can partner with community ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent the progression to problematic opioid use and OUD. Specifically, hospitals can do as follows:

- Provide evidence-based training to community providers on safe prescribing practices for acute and chronic pain management, as well as postoperative, postprocedural, and postpartum pain management

- Support ambulatory providers in expanding office-based mental health treatment through direct care via telemedicine and in building mental health treatment capacity through consultation, continuing medical education, and telementorship (eg, Project ECHO15)

- Support ambulatory providers to implement risk reduction strategies to prevent initiation of problematic opioid use, particularly among adolescents and young adults

- Partner with local pharmacies to promote point-of-prescription counseling on the risks and benefits of opioids

Hospitals bring key strengths and resources to these prevention-oriented partnerships. First, they may have resources available for clinical research, implementation support, program evaluation, and quality improvement, bringing such expertise to partnerships with ambulatory practices and pharmacies. They likely have specific expertise among their staff, including areas such as pain management, obstetric care, pediatrics, and adolescent medicine, and can provide specialists for consultation services or telementoring initiatives. They also can organize continuing medical education and can offer in-service training at local practices and pharmacies.

Project ECHO is one example of telementoring to build capacity among community providers to manage chronic pain and address addiction and other related harms.16 The Project ECHO model includes virtual sessions with didactic content and case presentations during which specialists mentor community clinicians. Specific to primary prevention, telementoring has been shown to improve access to evidence-based treatment of chronic pain and mental health conditions,17,18 which could prevent the development of OUD. By equipping community clinicians with tools to prevent the development of problematic opioid use, hospitals can help reduce the downstream burden of OUD and its associated morbidity, mortality, and costs.

CONCLUSION

The opioid crisis has devastated families, reduced life expectancy in certain communities,19 and had a substantial financial impact on hospitals—resulting in an estimated $11 billion in costs to US hospitals each year.20 This ongoing crisis is only going to be compounded by the recent emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Hospital resources are being strained in unprecedented ways, which has required unprecedented responses in order to continue to serve their communities. Supporting economic opportunity, stable housing, and mental health treatment will be challenging in this new environment but has never been more urgently needed. If opioid settlement funds are targeted to US hospitals, they should be held accountable for where funds are spent because they have a unique opportunity to focus on primary prevention in their communities—confronting OUD before it begins.21 However, if hospitals use opioid settlement funding only to continue to provide services already offered, or fail to make bold investments in their communities, this public health crisis will continue to strain the resources of those providing clinical care on the front lines.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Hilary Peterson of the RAND Corporation for preparing the paper for submission. She was not compensated for her contribution.

Disclosures

The authors report being supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under awards R21DA045212 (Dr Faherty), K23DA045085 (Dr Hadland), L40DA042434 (Dr Hadland), K23DA038720 (Dr Patrick), R01DA045729 (Dr Patrick), and P50DA046351 (Dr Stein). Dr Hadland also reports grant support from the Thrasher Research Fund and the Academic Pediatric Association. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

1. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427. http://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1

2. Kasich J, Gee EG. Don’t forget our frontline caregivers in the opioid epidemic. New York Times. Published September 18, 2019. Accessed December 16, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/17/opinion/opioid-settlement-hospitals.html

3. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

4. Franz B, Cronin CE, Wainwright A, Pagan JA. Measuring efforts of nonprofit hospitals to address opioid abuse after the Affordable Care Act. J Prim Care Communit. 2019;10:2150132719863611. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132719863611

5. Venkataramani AS, Bair EF, O’Brien RL, Tsai ALC. Association between automotive assembly plant closures and opioid overdose mortality in the United States a difference-in-differences analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):254-262. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5686

6. Englander H, Gregg J, Gullickson J, et al. Recommendations for integrating peer mentors in hospital-based addiction care. Subst Abus. 2019:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1635968

7. Geisinger investing in employees’ careers with School at Work program. News Release. Geisinger; November 5, 2018. Updated November 5, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.geisinger.org/about-geisinger/news-and-media/news-releases/2018/11/19/17/31/geisinger-investing-in-employees-careers-with-school-at-work-program

8. Jackson A, Brasfield-Gorrigan H. Investing in the Future of the Healthcare Workforce: An Analysis of the Business Impact of Select Employee Development Programs at TriHealth in 2013. TriHealth. March 30, 2015. Accessed 20 April 2020. http://www.catalystlearning.com/Portals/0/Documents/TriHealth%20RoI%20Study%20Updated%20Version.pdf

9. Roy B, Stanojevich J, Stange P, Jiwani N, King R, Koo D. Development of the Community Health Improvement Navigator Database of Interventions. MMWR Suppl. 2016;65:1-9. http://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6502a1

10. Sandel M, Desmond M. Investing in housing for health improves both mission and margin. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2291-2292. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.15771

11. Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):235-237. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1576

12. Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771-1778. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.561

13. Health Research & Educational Trust. Social Determinants of Health Series: Housing and the Role of Hospitals. American Hospital Association. August 2017. Accessed December 16, 2019. https://www.aha.org/ahahret-guides/2017-08-22-social-determinants-health-series-housing-and-role-hospitals

14. Boston Medical Center to Invest $6.5 Million in Affordable Housing to Improve Community Health and Patient Outcomes, Reduce Medical Costs. Press release. Boston Medical Center; December 7, 2017. Accessed March 4, 2020. https://www.bmc.org/news/press-releases/2017/12/07/boston-medical-center-invest-65-million-affordable-housing-improve

15. Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2199-2207. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1009370

16. Chronic Pain and Opioid Management. Project ECHO. Accessed February 16, 2020. https://echo.unm.edu/teleecho-programs/chronic-pain

17. Anderson D, Zlateva I, Davis B, et al. Improving pain care with Project ECHO in community health centers. Pain Med. 2017;18(10):1882-1889. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx187

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12715

19. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.16932

20. Opioid Overdoses Costing US Hospitals an Estimated $11 Billion Annually. Press Release. Premier; January 3, 2019. Accessed March 4, 2020. https://www.premierinc.com/newsroom/press-releases/opioid-overdoses-costing-u-s-hospitals-an-estimated-11-billion-annually

21. Butler JC. 2017 ASTHO president’s challenge: public health approaches to preventing substance misuse and addiction. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5):531-536. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000000631

There is growing momentum to hold drug manufacturers accountable for the more than 400,000 US opioid overdose deaths that have occurred since 1999.1 As state lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors wind their way through the legal system, hospitals—which may benefit from settlement funds—have been paying close attention. Recently, former Governor John Kasich (R-Ohio), West Virginia University president E. Gordon Gee, and America’s Essential Hospitals argued that adequately compensating hospitals for the costs of being on the crisis’ “front lines” requires prioritizing them as settlement fund recipients.2

Hospitals should be laying the groundwork for how settlement funds might be used. They may consider enhancing some of the most promising, evidence-based services for individuals with opioid use disorders (OUDs), including improving treatment for commonly associated health conditions such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV); expanding ambulatory long-term antibiotic treatment for endocarditis and other intravenous drug use–associated infections; more broadly adopting harm-reduction practices such as naloxone coprescribing; and applying best practices to caring for substance-exposed infants. They could also develop clinical services not already provided, including creating programs for OUD management during pregnancy and initiating medication for OUD in inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory settings. In short, hospitals play a critical role in engaging people with OUD in treatment at every possible opportunity.3

When considering how to most effectively use opioid settlement funding, hospitals may consider adding or expanding these much-needed clinical services to address opioid-related harms; however, their efforts should not stop there. Investments made outside hospital walls could have a significant effect on the public’s health, especially if they target social determinants of health. By tackling factors in the pathway to developing OUD, such as lack of meaningful employment, affordable housing, and mental health care, hospitals can move beyond treating the downstream consequences of addiction and toward preventing community-level opioid-related harms. To accomplish this daunting goal, hospitals will need to strengthen existing relationships with community partners and build new ones. Yet in a 2015 study, only 54% of nonprofit hospitals proposed a strategy to address the overdose crisis that involved community partnering.4

In this Perspective, we describe the following three strategies hospitals can use to multiply the reach of their opioid settlement funding by addressing root causes of opioid use through primary prevention: (1) supporting economic opportunities in their communities, (2) expanding affordable housing options in surrounding neighborhoods, and (3) building capacity in ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent OUD (Table).

SUPPORTING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY IN THEIR COMMUNITIES

Lack of economic opportunity is one of many root causes of opioid use. For example, a recent study found that automotive assembly plant closures were associated with increases in opioid overdose mortality.5 To tackle this complex issue, hospitals can play a crucial role in expanding employment and career advancement options for members of their local communities. Specifically, hospitals can do the following:

- Create jobs within the healthcare system and preferentially recruit and hire from surrounding neighborhoods

- Establish structured career development programs to build skills among entry-level healthcare employees

- Award contracts of varying sizes to locally owned businesses

- Employ individuals with lived experience with substance use disorders, such as peer recovery coaches6

To illustrate how health systems are investing in enhancing career opportunities for members of their communities, hundreds of institutions have implemented “School at Work,” a 6-month career development program for entry-level healthcare employees.7 The hospitals’ Human Resources department trains participants in communication skills, reading and writing, patient safety and satisfaction, medical terminology, and strategies for success and career advancement. Evaluations of this program have demonstrated improved employee outcomes and a favorable return on investment for hospitals.8

As “anchor institutions” and large employers in many communities, hospitals can simultaneously enhance their own workforce and offer employment opportunities that can help break the cycle of addiction that commonly traps individuals and families in communities affected by the overdose crisis.

EXPANDING AFFORDABLE HOUSING OPTIONS

Hospitals are increasingly supporting interventions that fall outside their traditional purview as they seek to improve population health, such as developing safe green outdoor spaces and increasing access to healthy food options by supporting local farmers markets and grocers.9 Stable, decent, and affordable housing is critically important to health and well-being,10 and there is a well-documented association of opioid use disorder and opioid misuse with housing instability.11 Given evidence of improved outcomes with hospital-led housing interventions,12 a growing number of hospitals are partnering with housing authorities and community groups to help do the following13:

- Contribute to supportive housing options

- Provide environmental health assessments, repairs, and renovations

- Buy or develop affordable housing units

Boston Medical Center, where one in four inpatients are experiencing homelessnes and one in three pediatric emergency department patients are housing insecure, provides an example of how a hospital has invested in housing.14 In 2017, the hospital began a 5-year, $6.5 million investment in community partnerships in surrounding neighborhoods. Instead of building housing units or acting as a landlord, the hospital chose to invest funding in creative ways to increase the pool of affordable housing. It invested $1 million to rehabilitate permanent, supportive housing units for individuals with mental health conditions in a nearby Boston neighborhood and in a housing stabilization program for people with complex medical issues including substance use disorder. It provided resources to a homeless shelter near the hospital and to the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, which provides healthcare to individuals with housing instability. It also funded a community wellness advocate based at the hospital, who received training in substance use disorders and served as a liaison between the hospital and the Boston Housing Authority.

Housing instability is just one of the social determinants of health that hospitals have the capacity to address as they consider where to invest their opioid settlement funds.

BUILDING PREVENTION CAPACITY IN THE COMMUNITY

Finally, hospitals can partner with community ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent the progression to problematic opioid use and OUD. Specifically, hospitals can do as follows:

- Provide evidence-based training to community providers on safe prescribing practices for acute and chronic pain management, as well as postoperative, postprocedural, and postpartum pain management

- Support ambulatory providers in expanding office-based mental health treatment through direct care via telemedicine and in building mental health treatment capacity through consultation, continuing medical education, and telementorship (eg, Project ECHO15)

- Support ambulatory providers to implement risk reduction strategies to prevent initiation of problematic opioid use, particularly among adolescents and young adults

- Partner with local pharmacies to promote point-of-prescription counseling on the risks and benefits of opioids

Hospitals bring key strengths and resources to these prevention-oriented partnerships. First, they may have resources available for clinical research, implementation support, program evaluation, and quality improvement, bringing such expertise to partnerships with ambulatory practices and pharmacies. They likely have specific expertise among their staff, including areas such as pain management, obstetric care, pediatrics, and adolescent medicine, and can provide specialists for consultation services or telementoring initiatives. They also can organize continuing medical education and can offer in-service training at local practices and pharmacies.

Project ECHO is one example of telementoring to build capacity among community providers to manage chronic pain and address addiction and other related harms.16 The Project ECHO model includes virtual sessions with didactic content and case presentations during which specialists mentor community clinicians. Specific to primary prevention, telementoring has been shown to improve access to evidence-based treatment of chronic pain and mental health conditions,17,18 which could prevent the development of OUD. By equipping community clinicians with tools to prevent the development of problematic opioid use, hospitals can help reduce the downstream burden of OUD and its associated morbidity, mortality, and costs.

CONCLUSION

The opioid crisis has devastated families, reduced life expectancy in certain communities,19 and had a substantial financial impact on hospitals—resulting in an estimated $11 billion in costs to US hospitals each year.20 This ongoing crisis is only going to be compounded by the recent emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Hospital resources are being strained in unprecedented ways, which has required unprecedented responses in order to continue to serve their communities. Supporting economic opportunity, stable housing, and mental health treatment will be challenging in this new environment but has never been more urgently needed. If opioid settlement funds are targeted to US hospitals, they should be held accountable for where funds are spent because they have a unique opportunity to focus on primary prevention in their communities—confronting OUD before it begins.21 However, if hospitals use opioid settlement funding only to continue to provide services already offered, or fail to make bold investments in their communities, this public health crisis will continue to strain the resources of those providing clinical care on the front lines.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Hilary Peterson of the RAND Corporation for preparing the paper for submission. She was not compensated for her contribution.

Disclosures

The authors report being supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under awards R21DA045212 (Dr Faherty), K23DA045085 (Dr Hadland), L40DA042434 (Dr Hadland), K23DA038720 (Dr Patrick), R01DA045729 (Dr Patrick), and P50DA046351 (Dr Stein). Dr Hadland also reports grant support from the Thrasher Research Fund and the Academic Pediatric Association. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

There is growing momentum to hold drug manufacturers accountable for the more than 400,000 US opioid overdose deaths that have occurred since 1999.1 As state lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors wind their way through the legal system, hospitals—which may benefit from settlement funds—have been paying close attention. Recently, former Governor John Kasich (R-Ohio), West Virginia University president E. Gordon Gee, and America’s Essential Hospitals argued that adequately compensating hospitals for the costs of being on the crisis’ “front lines” requires prioritizing them as settlement fund recipients.2

Hospitals should be laying the groundwork for how settlement funds might be used. They may consider enhancing some of the most promising, evidence-based services for individuals with opioid use disorders (OUDs), including improving treatment for commonly associated health conditions such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV); expanding ambulatory long-term antibiotic treatment for endocarditis and other intravenous drug use–associated infections; more broadly adopting harm-reduction practices such as naloxone coprescribing; and applying best practices to caring for substance-exposed infants. They could also develop clinical services not already provided, including creating programs for OUD management during pregnancy and initiating medication for OUD in inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory settings. In short, hospitals play a critical role in engaging people with OUD in treatment at every possible opportunity.3

When considering how to most effectively use opioid settlement funding, hospitals may consider adding or expanding these much-needed clinical services to address opioid-related harms; however, their efforts should not stop there. Investments made outside hospital walls could have a significant effect on the public’s health, especially if they target social determinants of health. By tackling factors in the pathway to developing OUD, such as lack of meaningful employment, affordable housing, and mental health care, hospitals can move beyond treating the downstream consequences of addiction and toward preventing community-level opioid-related harms. To accomplish this daunting goal, hospitals will need to strengthen existing relationships with community partners and build new ones. Yet in a 2015 study, only 54% of nonprofit hospitals proposed a strategy to address the overdose crisis that involved community partnering.4

In this Perspective, we describe the following three strategies hospitals can use to multiply the reach of their opioid settlement funding by addressing root causes of opioid use through primary prevention: (1) supporting economic opportunities in their communities, (2) expanding affordable housing options in surrounding neighborhoods, and (3) building capacity in ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent OUD (Table).

SUPPORTING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY IN THEIR COMMUNITIES

Lack of economic opportunity is one of many root causes of opioid use. For example, a recent study found that automotive assembly plant closures were associated with increases in opioid overdose mortality.5 To tackle this complex issue, hospitals can play a crucial role in expanding employment and career advancement options for members of their local communities. Specifically, hospitals can do the following:

- Create jobs within the healthcare system and preferentially recruit and hire from surrounding neighborhoods

- Establish structured career development programs to build skills among entry-level healthcare employees

- Award contracts of varying sizes to locally owned businesses

- Employ individuals with lived experience with substance use disorders, such as peer recovery coaches6

To illustrate how health systems are investing in enhancing career opportunities for members of their communities, hundreds of institutions have implemented “School at Work,” a 6-month career development program for entry-level healthcare employees.7 The hospitals’ Human Resources department trains participants in communication skills, reading and writing, patient safety and satisfaction, medical terminology, and strategies for success and career advancement. Evaluations of this program have demonstrated improved employee outcomes and a favorable return on investment for hospitals.8

As “anchor institutions” and large employers in many communities, hospitals can simultaneously enhance their own workforce and offer employment opportunities that can help break the cycle of addiction that commonly traps individuals and families in communities affected by the overdose crisis.

EXPANDING AFFORDABLE HOUSING OPTIONS

Hospitals are increasingly supporting interventions that fall outside their traditional purview as they seek to improve population health, such as developing safe green outdoor spaces and increasing access to healthy food options by supporting local farmers markets and grocers.9 Stable, decent, and affordable housing is critically important to health and well-being,10 and there is a well-documented association of opioid use disorder and opioid misuse with housing instability.11 Given evidence of improved outcomes with hospital-led housing interventions,12 a growing number of hospitals are partnering with housing authorities and community groups to help do the following13:

- Contribute to supportive housing options

- Provide environmental health assessments, repairs, and renovations

- Buy or develop affordable housing units

Boston Medical Center, where one in four inpatients are experiencing homelessnes and one in three pediatric emergency department patients are housing insecure, provides an example of how a hospital has invested in housing.14 In 2017, the hospital began a 5-year, $6.5 million investment in community partnerships in surrounding neighborhoods. Instead of building housing units or acting as a landlord, the hospital chose to invest funding in creative ways to increase the pool of affordable housing. It invested $1 million to rehabilitate permanent, supportive housing units for individuals with mental health conditions in a nearby Boston neighborhood and in a housing stabilization program for people with complex medical issues including substance use disorder. It provided resources to a homeless shelter near the hospital and to the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, which provides healthcare to individuals with housing instability. It also funded a community wellness advocate based at the hospital, who received training in substance use disorders and served as a liaison between the hospital and the Boston Housing Authority.

Housing instability is just one of the social determinants of health that hospitals have the capacity to address as they consider where to invest their opioid settlement funds.

BUILDING PREVENTION CAPACITY IN THE COMMUNITY

Finally, hospitals can partner with community ambulatory practices and pharmacies to prevent the progression to problematic opioid use and OUD. Specifically, hospitals can do as follows:

- Provide evidence-based training to community providers on safe prescribing practices for acute and chronic pain management, as well as postoperative, postprocedural, and postpartum pain management

- Support ambulatory providers in expanding office-based mental health treatment through direct care via telemedicine and in building mental health treatment capacity through consultation, continuing medical education, and telementorship (eg, Project ECHO15)

- Support ambulatory providers to implement risk reduction strategies to prevent initiation of problematic opioid use, particularly among adolescents and young adults

- Partner with local pharmacies to promote point-of-prescription counseling on the risks and benefits of opioids

Hospitals bring key strengths and resources to these prevention-oriented partnerships. First, they may have resources available for clinical research, implementation support, program evaluation, and quality improvement, bringing such expertise to partnerships with ambulatory practices and pharmacies. They likely have specific expertise among their staff, including areas such as pain management, obstetric care, pediatrics, and adolescent medicine, and can provide specialists for consultation services or telementoring initiatives. They also can organize continuing medical education and can offer in-service training at local practices and pharmacies.

Project ECHO is one example of telementoring to build capacity among community providers to manage chronic pain and address addiction and other related harms.16 The Project ECHO model includes virtual sessions with didactic content and case presentations during which specialists mentor community clinicians. Specific to primary prevention, telementoring has been shown to improve access to evidence-based treatment of chronic pain and mental health conditions,17,18 which could prevent the development of OUD. By equipping community clinicians with tools to prevent the development of problematic opioid use, hospitals can help reduce the downstream burden of OUD and its associated morbidity, mortality, and costs.

CONCLUSION

The opioid crisis has devastated families, reduced life expectancy in certain communities,19 and had a substantial financial impact on hospitals—resulting in an estimated $11 billion in costs to US hospitals each year.20 This ongoing crisis is only going to be compounded by the recent emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Hospital resources are being strained in unprecedented ways, which has required unprecedented responses in order to continue to serve their communities. Supporting economic opportunity, stable housing, and mental health treatment will be challenging in this new environment but has never been more urgently needed. If opioid settlement funds are targeted to US hospitals, they should be held accountable for where funds are spent because they have a unique opportunity to focus on primary prevention in their communities—confronting OUD before it begins.21 However, if hospitals use opioid settlement funding only to continue to provide services already offered, or fail to make bold investments in their communities, this public health crisis will continue to strain the resources of those providing clinical care on the front lines.

Acknowledgment