User login

Medical Communities Go Virtual

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

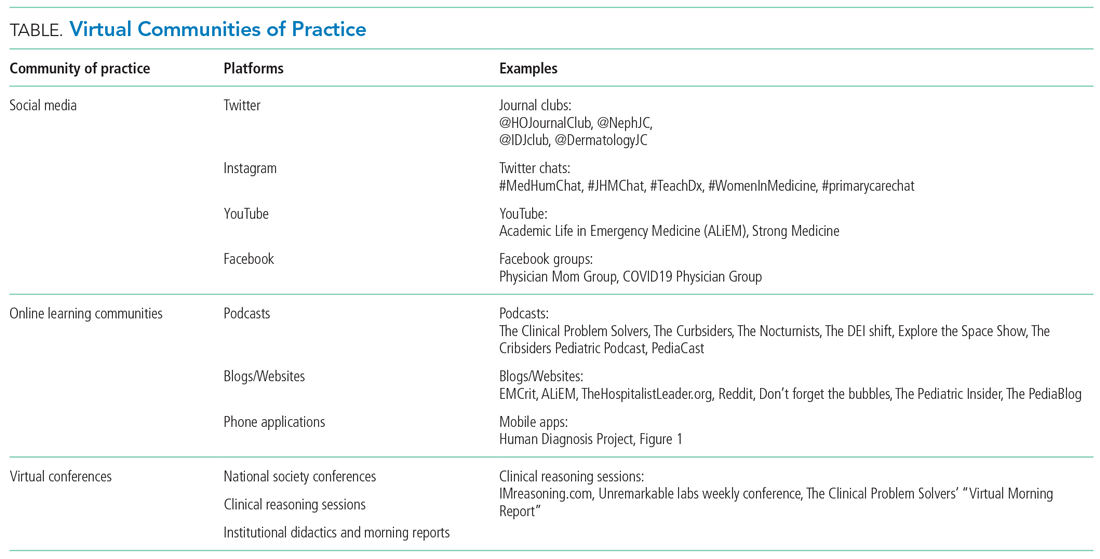

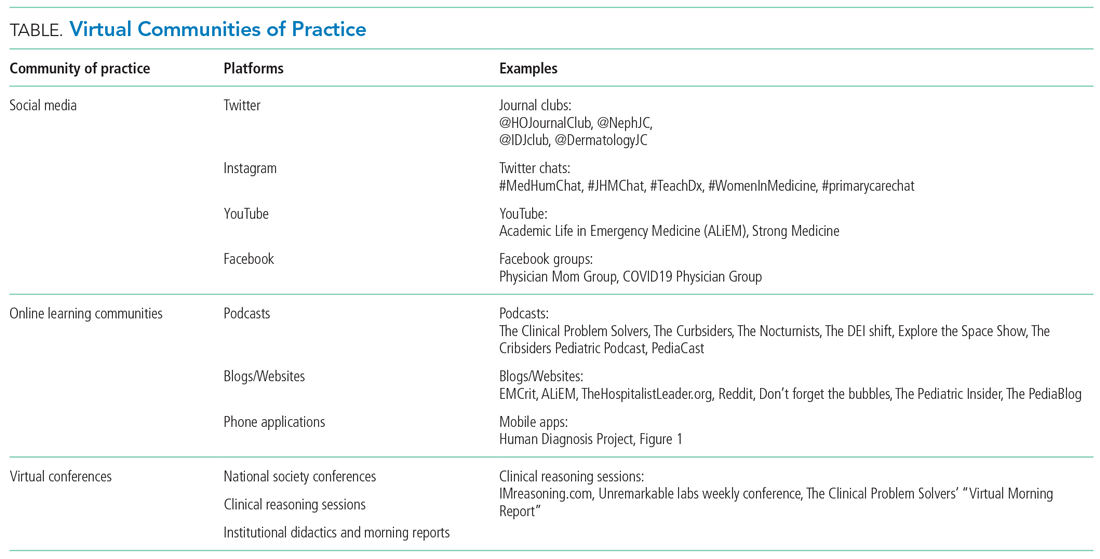

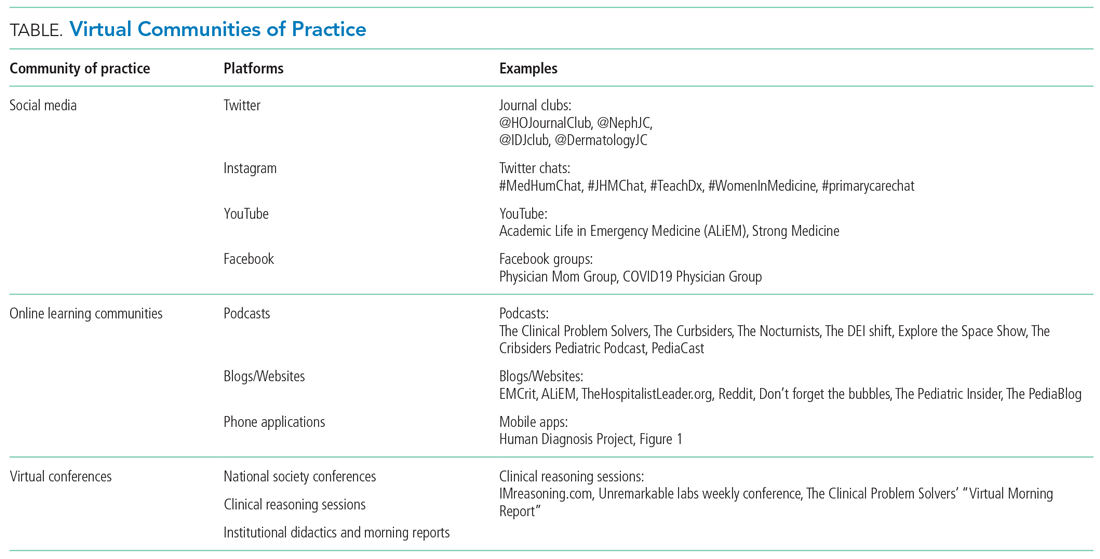

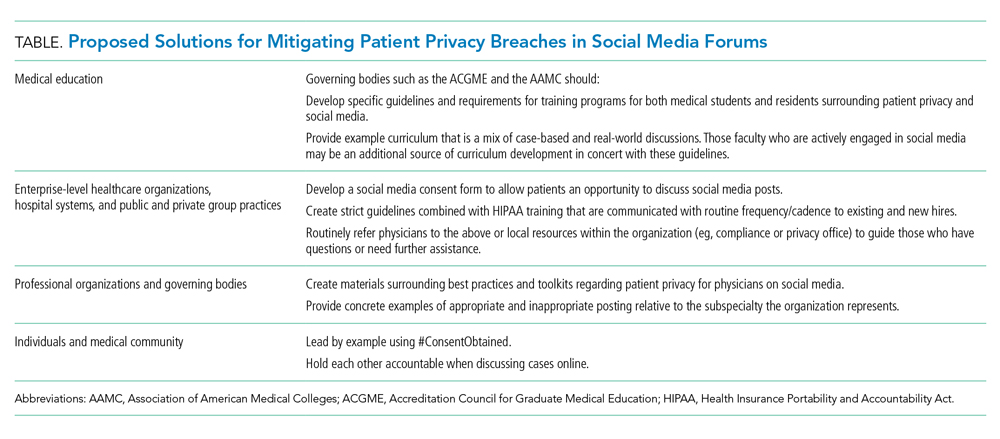

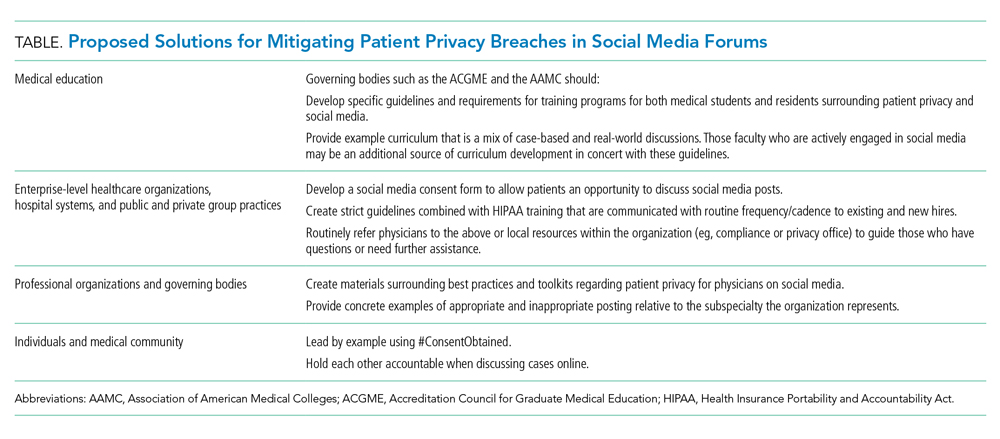

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Converging Crises: Caring for Hospitalized Adults With Substance Use Disorder in the Time of COVID-19

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities

Many of the inequities that increase people’s risk for undertreated SUD also increase risk for COVID-19 infection, including racism,12 poverty, and homelessness.4 “Stay home and stay safe” is not an option for people who are unsheltered or whose homes are unsafe because of risks of physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Poverty commonly forces people to live in crowded communal apartments or shelters, rely on public transportation, wait in long lines at food pantries, and continue to work, even if unwell. Many shelters have had to reduce the number of people they serve to reduce crowding and support social distancing, which further compounds risks of unstable housing. Unfortunately, the same structural inequities that exacerbate SUD worsen the COVID-19 crisis.13

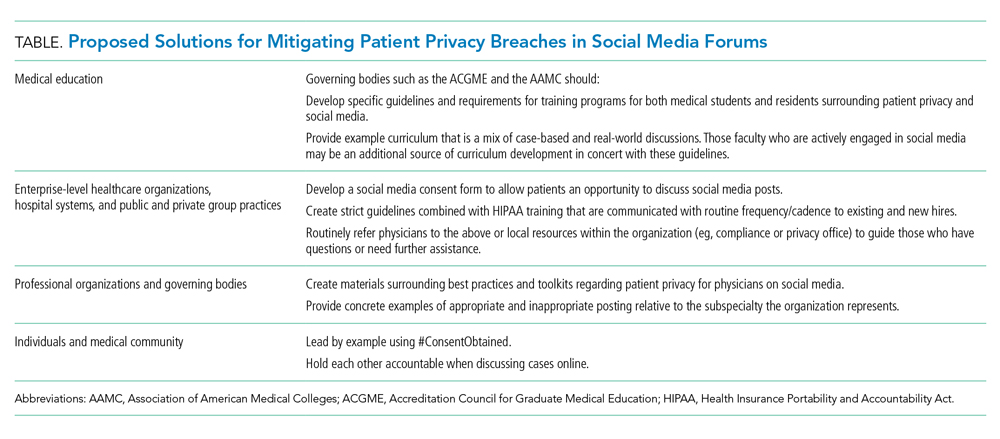

ROLE FOR HOSPITALISTS

The intersecting vulnerabilities of SUD and COVID-19 heighten an already urgent need to address SUD among hospitalized patients.14 While COVID-19 may increase harms of substance use, it may also increase people’s readiness to engage in treatment given changes to the drug supply and patient’s concerns about health risks. As such, it is even more critical to make treatment readily accessible and support harm reduction. Hospitalists can take important, actionable steps for patients with SUD—many of which are good general practices14 (Appendix Table).

Hospitalists should do the following:

1. Identify and treat acute withdrawal.15

2. Manage acute pain, including providing high-dose opioids if needed.16 Both practices (1 and 2) are evidence-based, can promote patient’s trust in providers,17 and can help avoid patients leaving against medical advice (AMA). Leaving AMA can lead to poor individual health and further threaten public health if patients leave with undiagnosed or unmanaged COVID-19 infection.

3. Encourage their hospitals to provide patients with tablets or other means to communicate with family, friends, and recovery supports via videolink, and refer patients to virtual peer support and recovery meetings during hospitalization.18 These practices may further support patients in tolerating hospitalization and prevent AMA discharge.

4. Initiate medication for addiction during admission and refer to addictions treatment after discharge. COVID-19–related regulatory changes such as expanded telehealth buprenorphine options and fewer daily dosing requirements for methadone may make this easier. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol and tobacco use disorders,15 especially given heightened possibility of unhealthy alcohol use and the respiratory complications associated with both tobacco and COVID-19.

5. Assess mental health and suicide risks19 given their association with social isolation, job loss, and financial insecurity.

6. Discuss relapse prevention among people in recovery.

7. Assess overdose risk and promote harm reduction.19 Specifically, this may include counseling patients to avoid sharing smoking supplies to avoid COVID-19 transmission, identifying places to access clean syringes, prescribing naloxone,20 and providing supports so that, if patients need to use alone, they can do so more safely.21

8. Consider high-risk transitions that may be exacerbated by COVID-19. COVID-19 may make safe discharge plans among people experiencing homelessness very challenging. Some communities are rapidly repurposing existing spaces or building new ones to care for people without a safe place to recover after acute hospitalization, yet many communities have no such resources. Hospital teams should consider the possibility that community services and SUD treatment resources may change rapidly during the pandemic. Hospitals can maintain updated resource lists and consider partnering with state and local health departments to improve safe care for people experiencing homelessness or lacking basic services.

COVID-19 is putting enormous strain on many US hospitals. Hospital-based addictions care is under resourced in the best of times,14 and while some hospitals have addiction consult services, many do not. To what degree hospitalists and hospital teams can address anything beyond COVID-19 emergencies will vary based on settings and resources. Furthermore, we recognize that who performs various activities will depend on individual hospital’s resources and practices. Addiction consult services, if available, can play a critical role, as can hospital social workers and care managers, nurses, residents, students, and other members of the healthcare team.

Finally, though COVID-19 adds tremendous stress to hospitals, permanent improvements in SUD treatment systems such as telephone visits for buprenorphine or eased methadone restrictions may emerge that could reduce barriers to hospital-based addictions care.11 Leveraging these changes now may help hospital providers to better support patients long-term.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization can be a challenging time for patients with SUD and for the hospital teams who care for them. These tensions are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet hospitalists play a critical role in addressing the converging crises of SUD and COVID-19. Providing comprehensive, compassionate, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with SUD is important for both individual and community health during COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr King received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (UG1DA015815) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037441). Dr Snyder received a Public Health Institute grant payable to her institution.

1. Bahorik AL, Satre DD, Kline-Simon AH, Weisner CM, Campbell CI. Alcohol, cannabis, and opioid use disorders, and disease burden in an integrated health care system. J Addict Med. 2017;11(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000260

2. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424

3. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

4. Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30085-2

5. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

6. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Intersecting U.S. epidemics: COVID-19 and lack of health insurance. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):63-64. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1491

7. McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;105:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.010

8. Harm Reduction Coalition. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://harmreduction.org/

9. COVID-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use. Global Research Network, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020. http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf

10. Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Nikolopoulos GK, Friedman SR. Immediate impact of hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878-884. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.978675

11. FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf

12. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. Published online April 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

13. Baggett TP, Lewis E, Gaeta JM. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness: early evidence from Boston. Ann Fam Med. Preprint posted April 4, 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/154734

14. Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists’ role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):184-187. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3311

15. Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001

16. Quality & Science. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.asam.org/Quality-Science/quality

17. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. Published online December 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

18. Digital Recovery Support Services. Recovery Link. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://myrecoverylink.com/digital-recovery-support/

19. Publications and Digital Products: Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. September 2009. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAFE-T-Pocket-Card-Suicide-Assessment-Five-Step-Evaluation-and-Triage-for-Clinicians/sma09-4432

20. Prescribe to Prevent: Prescribe Naloxone, Save a Life. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://prescribetoprevent.org/

21. Never Use Alone. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://neverusealone.com/

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities

Many of the inequities that increase people’s risk for undertreated SUD also increase risk for COVID-19 infection, including racism,12 poverty, and homelessness.4 “Stay home and stay safe” is not an option for people who are unsheltered or whose homes are unsafe because of risks of physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Poverty commonly forces people to live in crowded communal apartments or shelters, rely on public transportation, wait in long lines at food pantries, and continue to work, even if unwell. Many shelters have had to reduce the number of people they serve to reduce crowding and support social distancing, which further compounds risks of unstable housing. Unfortunately, the same structural inequities that exacerbate SUD worsen the COVID-19 crisis.13

ROLE FOR HOSPITALISTS

The intersecting vulnerabilities of SUD and COVID-19 heighten an already urgent need to address SUD among hospitalized patients.14 While COVID-19 may increase harms of substance use, it may also increase people’s readiness to engage in treatment given changes to the drug supply and patient’s concerns about health risks. As such, it is even more critical to make treatment readily accessible and support harm reduction. Hospitalists can take important, actionable steps for patients with SUD—many of which are good general practices14 (Appendix Table).

Hospitalists should do the following:

1. Identify and treat acute withdrawal.15

2. Manage acute pain, including providing high-dose opioids if needed.16 Both practices (1 and 2) are evidence-based, can promote patient’s trust in providers,17 and can help avoid patients leaving against medical advice (AMA). Leaving AMA can lead to poor individual health and further threaten public health if patients leave with undiagnosed or unmanaged COVID-19 infection.

3. Encourage their hospitals to provide patients with tablets or other means to communicate with family, friends, and recovery supports via videolink, and refer patients to virtual peer support and recovery meetings during hospitalization.18 These practices may further support patients in tolerating hospitalization and prevent AMA discharge.

4. Initiate medication for addiction during admission and refer to addictions treatment after discharge. COVID-19–related regulatory changes such as expanded telehealth buprenorphine options and fewer daily dosing requirements for methadone may make this easier. Further, hospitalists should offer medication for alcohol and tobacco use disorders,15 especially given heightened possibility of unhealthy alcohol use and the respiratory complications associated with both tobacco and COVID-19.

5. Assess mental health and suicide risks19 given their association with social isolation, job loss, and financial insecurity.

6. Discuss relapse prevention among people in recovery.

7. Assess overdose risk and promote harm reduction.19 Specifically, this may include counseling patients to avoid sharing smoking supplies to avoid COVID-19 transmission, identifying places to access clean syringes, prescribing naloxone,20 and providing supports so that, if patients need to use alone, they can do so more safely.21

8. Consider high-risk transitions that may be exacerbated by COVID-19. COVID-19 may make safe discharge plans among people experiencing homelessness very challenging. Some communities are rapidly repurposing existing spaces or building new ones to care for people without a safe place to recover after acute hospitalization, yet many communities have no such resources. Hospital teams should consider the possibility that community services and SUD treatment resources may change rapidly during the pandemic. Hospitals can maintain updated resource lists and consider partnering with state and local health departments to improve safe care for people experiencing homelessness or lacking basic services.

COVID-19 is putting enormous strain on many US hospitals. Hospital-based addictions care is under resourced in the best of times,14 and while some hospitals have addiction consult services, many do not. To what degree hospitalists and hospital teams can address anything beyond COVID-19 emergencies will vary based on settings and resources. Furthermore, we recognize that who performs various activities will depend on individual hospital’s resources and practices. Addiction consult services, if available, can play a critical role, as can hospital social workers and care managers, nurses, residents, students, and other members of the healthcare team.

Finally, though COVID-19 adds tremendous stress to hospitals, permanent improvements in SUD treatment systems such as telephone visits for buprenorphine or eased methadone restrictions may emerge that could reduce barriers to hospital-based addictions care.11 Leveraging these changes now may help hospital providers to better support patients long-term.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization can be a challenging time for patients with SUD and for the hospital teams who care for them. These tensions are exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, yet hospitalists play a critical role in addressing the converging crises of SUD and COVID-19. Providing comprehensive, compassionate, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with SUD is important for both individual and community health during COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alisa Patten for help preparing this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr King received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (UG1DA015815) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037441). Dr Snyder received a Public Health Institute grant payable to her institution.

The spread of SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind the COVID-19 pandemic, has converged with an unrelenting addiction epidemic. These combined crises will have profound effects on people with substance use disorders (SUD) and people in recovery. Hospitals—which were already hit hard by the addiction epidemic—are the last line of defense in the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitalists have an important role in balancing the effects of these intersecting, synergistic crises.

People with SUD are disproportionately affected by major medical illnesses, including infections such as hepatitis C, HIV, and cardiovascular, pulmonary, and liver diseases.1 They also experience high rates of hospitalization due to drug-related infections, injury, and overdose.2 People with SUD commonly have intersecting vulnerabilities that may affect their healthcare experience and health outcomes, including housing and food insecurity, mental illness, and experiences of racism, incarceration, and other trauma. They may also harbor mistrust of healthcare providers because of previous negative encounters and discrimination with health systems.3 These vulnerabilities increase risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic may drive increases in use and harms from SUD among patients who already have an SUD, with widespread job loss, insurance loss,6 anxiety, and social isolation on the rise. We may also see increases in return to use among people in recovery or new substance use among those without a history of SUD.

The intersecting crises of SUD and COVID-19 are important for people with SUD and for public health. In this perspective, we describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people with SUD and share practical resources for hospital providers to improve care for people with SUD during the pandemic and beyond.

CONTEXTUALIZING COVID-19 AND SUD RISK

Mistrust of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers

Fear of stigmatization is an ongoing problem for people with SUD, who often experience discrimination in hospitals and, as a result, may avoid hospital care.7 Much of this stigma is based on the false but persistent belief—widespread even among healthcare providers—that addiction is the result of bad choices and limited willpower; however, the science is clear that addiction is a disorder with neurobiological, genetic, and environmental underpinnings.3 These attitudes are likely to be amplified during COVID-19, as patients and providers experience higher levels of stress.

Increased Risks of Substance Use

Typically, people who use drugs are counseled to use with others nearby so that they might administer naloxone or call 911 in the event of an overdose.8 With physical distancing, people may be more likely to use alone. COVID-19 also introduces uncertainty into the drug supply chain through changes in drug production and trafficking.9 Further, access to alcohol may be limited as liquor stores close and public transportation becomes less available. As has been shown in other complex emergencies (such as social, political, economic, and environmental disasters), these barriers to obtaining substances may increase risks for withdrawal, for needing to exchange sex for money or drugs, for sharing syringes or drug preparation equipment,10 or for consuming other available sources of substances, like rubbing alcohol or hand sanitizer. COVID-19 may also increase risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidality, all of which increase risk for return to use and overdose.

Changes to the Treatment Milieu

Many of the resources and services that people who use substances rely on to keep safe may be disrupted by COVID-19. Social distancing—the cornerstone of mitigating COVID-19 spread—may be challenging among people with SUD. Though federal regulations around methadone dispensing and buprenorphine prescribing have loosened in response to the pandemic,11 individuals in treatment may still be required to provide urine drug screens or be physically present to receive methadone doses, sometimes daily and in crowded waiting rooms.

Recovery support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) provide social connection and are the foundation of many people’s recovery. While many in-person meetings have rapidly transformed to online and telephone support, they remain inaccessible to the most marginalized members of communities: people without smart phones, computers, or internet. This digital shift may also disproportionately affect older adults, people with limited English proficiency, and people with low technological literacy. Limits for other resources, such as syringe service programs, community centers, food pantries, housing shelters, and other places that people depend on for clean water, food, showers, soap, and safer spaces to use, may limit services or close altogether; those that remain open may see an unprecedented rise in need for services as millions of Americans file for unemployment. For many, anxiety about the pandemic, unemployment, financial strain, increased isolation, family stressors, illness, and community losses can lead to enormous personal distress and trigger return to use; loss of a recovery network may further exacerbate this.

Intersectionality of SUD and Other Structural Inequities