User login

Pseudomonas infection in patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a clinically important organism that infects patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB). In the United States, the estimated prevalence of NCFB is 213 per 100,000 across all age groups and 813 per 100,000 in the over 65 age group.1 A retrospective cohort study suggests the incidence of NCFB as ascertained from International Classification of Diseases codes may significantly underestimate its true prevalence.2

As the incidence of patients with NCFB continues to increase, the impact of the Pseudomonas infection is expected to grow. A recent retrospective cohort study of commercial claims from IQVIA’s PharMetrics Plus database for the period 2006 to 2020 showed that patients with NCFB and Pseudomonas infection had on average 2.58 hospital admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 9.94 (± 11.06) days, compared with 1.18 admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 6.5 (± 8.42) days, in patients with Pseudomonas-negative NCFB. The same trend applied to 30-day readmissions and ICU admissions, 1.32 (± 2.51 days) vs 0.47 (± 1.30 days) and 0.95 (± 1.62 days) vs 0.33 (± 0.76 days), respectively. The differential cost of care per patient per year between patients with NCFB with and without Pseudomonas infection ranged from $55,225 to $315,901.3

Recent data from the United States Bronchiectasis Registry showed the probability of acquiring Pseudomonas aeruginosa was 3% annually.4 The prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in a large, geographically diverse cohort in the United States was quoted at 15%.5 A retrospective analysis of the European Bronchiectasis Registry database showed Pseudomonas infection was the most commonly isolated pathogen (21.8%).6

Given the high incidence and prevalence of NCFB, the high prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in patients with NCFB, and the associated costs and morbidity from infection, identifying effective treatments has become a priority. The British, Spanish (SEPAR), South African, and European bronchiectasis guidelines outline several antibiotic regimens meant to achieve eradication. Generally, there is induction with a (1) quinolone, (2) β-lactam + aminoglycoside, or (3) quinolone with an inhaled antibiotic followed by three months of maintenance inhaled antibiotics.7-10 SEPAR allows for retreatment for recurrence at any time during the first year with any regimen.

For chronic Pseudomonas infection, SEPAR recommends treatment with inhaled antibiotics for patients with more than two exacerbations or one hospitalization, while the threshold in the British and European guidelines is more than three exacerbations. Azithromycin may be used for those who are intolerant or allergic to the nebulized antibiotics. It is worth noting that in the United States, the antibiotics colistin, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam, gentamicin, and tobramycin are administered off label for this indication. A systematic review found a 10% rate of bronchospasm in the treated group compared with 2.3% in the control group, and premedication with albuterol is often needed.11

Unfortunately, the data supporting the listed eradication and suppressive regimens are weak. A systematic review and meta-analysis of six observational studies including 289 patients showed a 12-month eradication rate of only 40% (95% CI, 34-45; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0).12 These results are disappointing and identify a need for further research into the manner in which Pseudomonas infection interacts with the host lung.

We currently know Pseudomonas infection evades antibiotics and host defenses by accumulating mutations and deletions. These include loss-of-function mutations in mucA (mucoidy), lasR (quorum-sensing), mexS (regulates the antibiotic efflux pump), and other genes related to the production of the polysaccharides Psl and Pel (which contribute to biofilm formation).13 There may also be differences in low and high bacteria microbial networks that interact differently with host cytokines to create an unstable environment that predisposes to exacerbation.14

In an attempt to improve our eradication and suppression rates, investigators have begun to target specific aspects of Pseudomonas infection behavior. The GREAT-2 trial compares gremubamab (a bivalent, bispecific, monoclonal antibody targeting Psl exopolysaccharide and the type 3 secretion system component of PcrV) with placebo in patients with chronic Pseudomonas infection. A phase II trial with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor esifentrine, a phase III trial with a reversible DPP1 inhibitor called brensocatib (ASPEN), and a phase II trial with the CatC inhibitor BI 1291583 (Airleaf) are also being conducted. Each of these agents targets mediators of neutrophil inflammation.

In summary, NCFB with Pseudomonas infection is common and leads to an increase in costs, respiratory exacerbations, and hospitalizations. While eradication and suppression are recommended, they are difficult to achieve and require sustained durations of expensive medications that can be difficult to tolerate. Antibiotic therapies will continue to be studied (the ERASE randomized controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of tobramycin to eradicate Pseudomonas infection is currently underway), but targeted therapies represent a promising new approach to combating this stubbornly resistant bacteria. The NCFB community will be watching closely to see whether medicines targeting molecular behavior and host interaction can achieve what antibiotic regimens thus far have not: consistent and sustainable eradication.

Dr. Green is Assistant Professor in Medicine, Medical Director, Bronchiectasis Program, UMass Chan/Baystate Health, Chest Infections Section, Member-at-Large

References

1. Weycker D, Hansen GL, Seifer FD. Prevalence and incidence of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis among US adults in 2013. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):377-384. doi: 10.1177/1479972317709649

2. Green O, Liautaud S, Knee A, Modahl L. Measuring accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes in identification of patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. ERJ Open Res. 2024;10(2):00715-2023. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00715-2023

3. Franklin M, Minshall ME, Pontenani F, Devarajan S. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on resource utilization and costs in patients with exacerbated non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. J Med Econ. 2024;27(1):671-677. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2024.2340382

4. Aksamit TR, Locantore N, Addrizzo-Harris D, et al. Five-year outcomes among U.S. bronchiectasis and NTM research registry patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Accepted manuscript. Published online April 26, 2024.

5. Dean SG, Blakney RA, Ricotta EE, et al. Bronchiectasis-associated infections and outcomes in a large, geographically diverse electronic health record cohort in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-02973-3

6. Chalmers JD, Polverino E, Crichton ML, et al. Bronchiectasis in Europe: data on disease characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(7):637-649. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00093-0

7. Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700629. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017

8. Martínez-García MÁ, Máiz L, Olveira C, et al. Spanish guidelines on treatment of bronchiectasis in adults. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(2):88-98. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.016

9. Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax. 2019;74(Suppl 1):1-69. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212463

10. Goolam Mahomed A, Maasdorp SD, Barnes R, et al. South African Thoracic Society position statement on the management of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in adults: 2023. Afr J Thorac Crit Care Med. 2023;29(2):10.7196/AJTCCM. 2023.v29i2.647. doi: 10.7196/AJTCCM.2023.v29i2.647

11. Brodt AM, Stovold E, Zhang L. Inhaled antibiotics for stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):382-393. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00018414

12. Conceição M, Shteinberg M, Goeminne P, Altenburg J, Chalmers JD. Eradication treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in adults with bronchiectasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33(171):230178. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0178-2023

13. Hilliam Y, Moore MP, Lamont IL, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adaptation and diversification in the non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(4):1602108. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2016

14. Gramegna A, Kumar Narayana J, Amati F, et al. Microbial inflammatory networks in bronchiectasis exacerbators with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2023;164(1):65-68. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.014

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a clinically important organism that infects patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB). In the United States, the estimated prevalence of NCFB is 213 per 100,000 across all age groups and 813 per 100,000 in the over 65 age group.1 A retrospective cohort study suggests the incidence of NCFB as ascertained from International Classification of Diseases codes may significantly underestimate its true prevalence.2

As the incidence of patients with NCFB continues to increase, the impact of the Pseudomonas infection is expected to grow. A recent retrospective cohort study of commercial claims from IQVIA’s PharMetrics Plus database for the period 2006 to 2020 showed that patients with NCFB and Pseudomonas infection had on average 2.58 hospital admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 9.94 (± 11.06) days, compared with 1.18 admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 6.5 (± 8.42) days, in patients with Pseudomonas-negative NCFB. The same trend applied to 30-day readmissions and ICU admissions, 1.32 (± 2.51 days) vs 0.47 (± 1.30 days) and 0.95 (± 1.62 days) vs 0.33 (± 0.76 days), respectively. The differential cost of care per patient per year between patients with NCFB with and without Pseudomonas infection ranged from $55,225 to $315,901.3

Recent data from the United States Bronchiectasis Registry showed the probability of acquiring Pseudomonas aeruginosa was 3% annually.4 The prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in a large, geographically diverse cohort in the United States was quoted at 15%.5 A retrospective analysis of the European Bronchiectasis Registry database showed Pseudomonas infection was the most commonly isolated pathogen (21.8%).6

Given the high incidence and prevalence of NCFB, the high prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in patients with NCFB, and the associated costs and morbidity from infection, identifying effective treatments has become a priority. The British, Spanish (SEPAR), South African, and European bronchiectasis guidelines outline several antibiotic regimens meant to achieve eradication. Generally, there is induction with a (1) quinolone, (2) β-lactam + aminoglycoside, or (3) quinolone with an inhaled antibiotic followed by three months of maintenance inhaled antibiotics.7-10 SEPAR allows for retreatment for recurrence at any time during the first year with any regimen.

For chronic Pseudomonas infection, SEPAR recommends treatment with inhaled antibiotics for patients with more than two exacerbations or one hospitalization, while the threshold in the British and European guidelines is more than three exacerbations. Azithromycin may be used for those who are intolerant or allergic to the nebulized antibiotics. It is worth noting that in the United States, the antibiotics colistin, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam, gentamicin, and tobramycin are administered off label for this indication. A systematic review found a 10% rate of bronchospasm in the treated group compared with 2.3% in the control group, and premedication with albuterol is often needed.11

Unfortunately, the data supporting the listed eradication and suppressive regimens are weak. A systematic review and meta-analysis of six observational studies including 289 patients showed a 12-month eradication rate of only 40% (95% CI, 34-45; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0).12 These results are disappointing and identify a need for further research into the manner in which Pseudomonas infection interacts with the host lung.

We currently know Pseudomonas infection evades antibiotics and host defenses by accumulating mutations and deletions. These include loss-of-function mutations in mucA (mucoidy), lasR (quorum-sensing), mexS (regulates the antibiotic efflux pump), and other genes related to the production of the polysaccharides Psl and Pel (which contribute to biofilm formation).13 There may also be differences in low and high bacteria microbial networks that interact differently with host cytokines to create an unstable environment that predisposes to exacerbation.14

In an attempt to improve our eradication and suppression rates, investigators have begun to target specific aspects of Pseudomonas infection behavior. The GREAT-2 trial compares gremubamab (a bivalent, bispecific, monoclonal antibody targeting Psl exopolysaccharide and the type 3 secretion system component of PcrV) with placebo in patients with chronic Pseudomonas infection. A phase II trial with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor esifentrine, a phase III trial with a reversible DPP1 inhibitor called brensocatib (ASPEN), and a phase II trial with the CatC inhibitor BI 1291583 (Airleaf) are also being conducted. Each of these agents targets mediators of neutrophil inflammation.

In summary, NCFB with Pseudomonas infection is common and leads to an increase in costs, respiratory exacerbations, and hospitalizations. While eradication and suppression are recommended, they are difficult to achieve and require sustained durations of expensive medications that can be difficult to tolerate. Antibiotic therapies will continue to be studied (the ERASE randomized controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of tobramycin to eradicate Pseudomonas infection is currently underway), but targeted therapies represent a promising new approach to combating this stubbornly resistant bacteria. The NCFB community will be watching closely to see whether medicines targeting molecular behavior and host interaction can achieve what antibiotic regimens thus far have not: consistent and sustainable eradication.

Dr. Green is Assistant Professor in Medicine, Medical Director, Bronchiectasis Program, UMass Chan/Baystate Health, Chest Infections Section, Member-at-Large

References

1. Weycker D, Hansen GL, Seifer FD. Prevalence and incidence of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis among US adults in 2013. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):377-384. doi: 10.1177/1479972317709649

2. Green O, Liautaud S, Knee A, Modahl L. Measuring accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes in identification of patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. ERJ Open Res. 2024;10(2):00715-2023. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00715-2023

3. Franklin M, Minshall ME, Pontenani F, Devarajan S. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on resource utilization and costs in patients with exacerbated non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. J Med Econ. 2024;27(1):671-677. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2024.2340382

4. Aksamit TR, Locantore N, Addrizzo-Harris D, et al. Five-year outcomes among U.S. bronchiectasis and NTM research registry patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Accepted manuscript. Published online April 26, 2024.

5. Dean SG, Blakney RA, Ricotta EE, et al. Bronchiectasis-associated infections and outcomes in a large, geographically diverse electronic health record cohort in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-02973-3

6. Chalmers JD, Polverino E, Crichton ML, et al. Bronchiectasis in Europe: data on disease characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(7):637-649. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00093-0

7. Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700629. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017

8. Martínez-García MÁ, Máiz L, Olveira C, et al. Spanish guidelines on treatment of bronchiectasis in adults. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(2):88-98. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.016

9. Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax. 2019;74(Suppl 1):1-69. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212463

10. Goolam Mahomed A, Maasdorp SD, Barnes R, et al. South African Thoracic Society position statement on the management of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in adults: 2023. Afr J Thorac Crit Care Med. 2023;29(2):10.7196/AJTCCM. 2023.v29i2.647. doi: 10.7196/AJTCCM.2023.v29i2.647

11. Brodt AM, Stovold E, Zhang L. Inhaled antibiotics for stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):382-393. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00018414

12. Conceição M, Shteinberg M, Goeminne P, Altenburg J, Chalmers JD. Eradication treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in adults with bronchiectasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33(171):230178. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0178-2023

13. Hilliam Y, Moore MP, Lamont IL, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adaptation and diversification in the non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(4):1602108. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2016

14. Gramegna A, Kumar Narayana J, Amati F, et al. Microbial inflammatory networks in bronchiectasis exacerbators with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2023;164(1):65-68. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.014

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a clinically important organism that infects patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB). In the United States, the estimated prevalence of NCFB is 213 per 100,000 across all age groups and 813 per 100,000 in the over 65 age group.1 A retrospective cohort study suggests the incidence of NCFB as ascertained from International Classification of Diseases codes may significantly underestimate its true prevalence.2

As the incidence of patients with NCFB continues to increase, the impact of the Pseudomonas infection is expected to grow. A recent retrospective cohort study of commercial claims from IQVIA’s PharMetrics Plus database for the period 2006 to 2020 showed that patients with NCFB and Pseudomonas infection had on average 2.58 hospital admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 9.94 (± 11.06) days, compared with 1.18 admissions per year, with a mean length of stay of 6.5 (± 8.42) days, in patients with Pseudomonas-negative NCFB. The same trend applied to 30-day readmissions and ICU admissions, 1.32 (± 2.51 days) vs 0.47 (± 1.30 days) and 0.95 (± 1.62 days) vs 0.33 (± 0.76 days), respectively. The differential cost of care per patient per year between patients with NCFB with and without Pseudomonas infection ranged from $55,225 to $315,901.3

Recent data from the United States Bronchiectasis Registry showed the probability of acquiring Pseudomonas aeruginosa was 3% annually.4 The prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in a large, geographically diverse cohort in the United States was quoted at 15%.5 A retrospective analysis of the European Bronchiectasis Registry database showed Pseudomonas infection was the most commonly isolated pathogen (21.8%).6

Given the high incidence and prevalence of NCFB, the high prevalence of Pseudomonas infection in patients with NCFB, and the associated costs and morbidity from infection, identifying effective treatments has become a priority. The British, Spanish (SEPAR), South African, and European bronchiectasis guidelines outline several antibiotic regimens meant to achieve eradication. Generally, there is induction with a (1) quinolone, (2) β-lactam + aminoglycoside, or (3) quinolone with an inhaled antibiotic followed by three months of maintenance inhaled antibiotics.7-10 SEPAR allows for retreatment for recurrence at any time during the first year with any regimen.

For chronic Pseudomonas infection, SEPAR recommends treatment with inhaled antibiotics for patients with more than two exacerbations or one hospitalization, while the threshold in the British and European guidelines is more than three exacerbations. Azithromycin may be used for those who are intolerant or allergic to the nebulized antibiotics. It is worth noting that in the United States, the antibiotics colistin, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam, gentamicin, and tobramycin are administered off label for this indication. A systematic review found a 10% rate of bronchospasm in the treated group compared with 2.3% in the control group, and premedication with albuterol is often needed.11

Unfortunately, the data supporting the listed eradication and suppressive regimens are weak. A systematic review and meta-analysis of six observational studies including 289 patients showed a 12-month eradication rate of only 40% (95% CI, 34-45; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0).12 These results are disappointing and identify a need for further research into the manner in which Pseudomonas infection interacts with the host lung.

We currently know Pseudomonas infection evades antibiotics and host defenses by accumulating mutations and deletions. These include loss-of-function mutations in mucA (mucoidy), lasR (quorum-sensing), mexS (regulates the antibiotic efflux pump), and other genes related to the production of the polysaccharides Psl and Pel (which contribute to biofilm formation).13 There may also be differences in low and high bacteria microbial networks that interact differently with host cytokines to create an unstable environment that predisposes to exacerbation.14

In an attempt to improve our eradication and suppression rates, investigators have begun to target specific aspects of Pseudomonas infection behavior. The GREAT-2 trial compares gremubamab (a bivalent, bispecific, monoclonal antibody targeting Psl exopolysaccharide and the type 3 secretion system component of PcrV) with placebo in patients with chronic Pseudomonas infection. A phase II trial with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor esifentrine, a phase III trial with a reversible DPP1 inhibitor called brensocatib (ASPEN), and a phase II trial with the CatC inhibitor BI 1291583 (Airleaf) are also being conducted. Each of these agents targets mediators of neutrophil inflammation.

In summary, NCFB with Pseudomonas infection is common and leads to an increase in costs, respiratory exacerbations, and hospitalizations. While eradication and suppression are recommended, they are difficult to achieve and require sustained durations of expensive medications that can be difficult to tolerate. Antibiotic therapies will continue to be studied (the ERASE randomized controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of tobramycin to eradicate Pseudomonas infection is currently underway), but targeted therapies represent a promising new approach to combating this stubbornly resistant bacteria. The NCFB community will be watching closely to see whether medicines targeting molecular behavior and host interaction can achieve what antibiotic regimens thus far have not: consistent and sustainable eradication.

Dr. Green is Assistant Professor in Medicine, Medical Director, Bronchiectasis Program, UMass Chan/Baystate Health, Chest Infections Section, Member-at-Large

References

1. Weycker D, Hansen GL, Seifer FD. Prevalence and incidence of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis among US adults in 2013. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):377-384. doi: 10.1177/1479972317709649

2. Green O, Liautaud S, Knee A, Modahl L. Measuring accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes in identification of patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. ERJ Open Res. 2024;10(2):00715-2023. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00715-2023

3. Franklin M, Minshall ME, Pontenani F, Devarajan S. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on resource utilization and costs in patients with exacerbated non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. J Med Econ. 2024;27(1):671-677. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2024.2340382

4. Aksamit TR, Locantore N, Addrizzo-Harris D, et al. Five-year outcomes among U.S. bronchiectasis and NTM research registry patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Accepted manuscript. Published online April 26, 2024.

5. Dean SG, Blakney RA, Ricotta EE, et al. Bronchiectasis-associated infections and outcomes in a large, geographically diverse electronic health record cohort in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-02973-3

6. Chalmers JD, Polverino E, Crichton ML, et al. Bronchiectasis in Europe: data on disease characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(7):637-649. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00093-0

7. Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700629. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017

8. Martínez-García MÁ, Máiz L, Olveira C, et al. Spanish guidelines on treatment of bronchiectasis in adults. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(2):88-98. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.016

9. Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax. 2019;74(Suppl 1):1-69. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212463

10. Goolam Mahomed A, Maasdorp SD, Barnes R, et al. South African Thoracic Society position statement on the management of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in adults: 2023. Afr J Thorac Crit Care Med. 2023;29(2):10.7196/AJTCCM. 2023.v29i2.647. doi: 10.7196/AJTCCM.2023.v29i2.647

11. Brodt AM, Stovold E, Zhang L. Inhaled antibiotics for stable non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):382-393. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00018414

12. Conceição M, Shteinberg M, Goeminne P, Altenburg J, Chalmers JD. Eradication treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in adults with bronchiectasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33(171):230178. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0178-2023

13. Hilliam Y, Moore MP, Lamont IL, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adaptation and diversification in the non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(4):1602108. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2016

14. Gramegna A, Kumar Narayana J, Amati F, et al. Microbial inflammatory networks in bronchiectasis exacerbators with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2023;164(1):65-68. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.014

Changing the tumor board conversation: Immunotherapy in resectable NSCLC

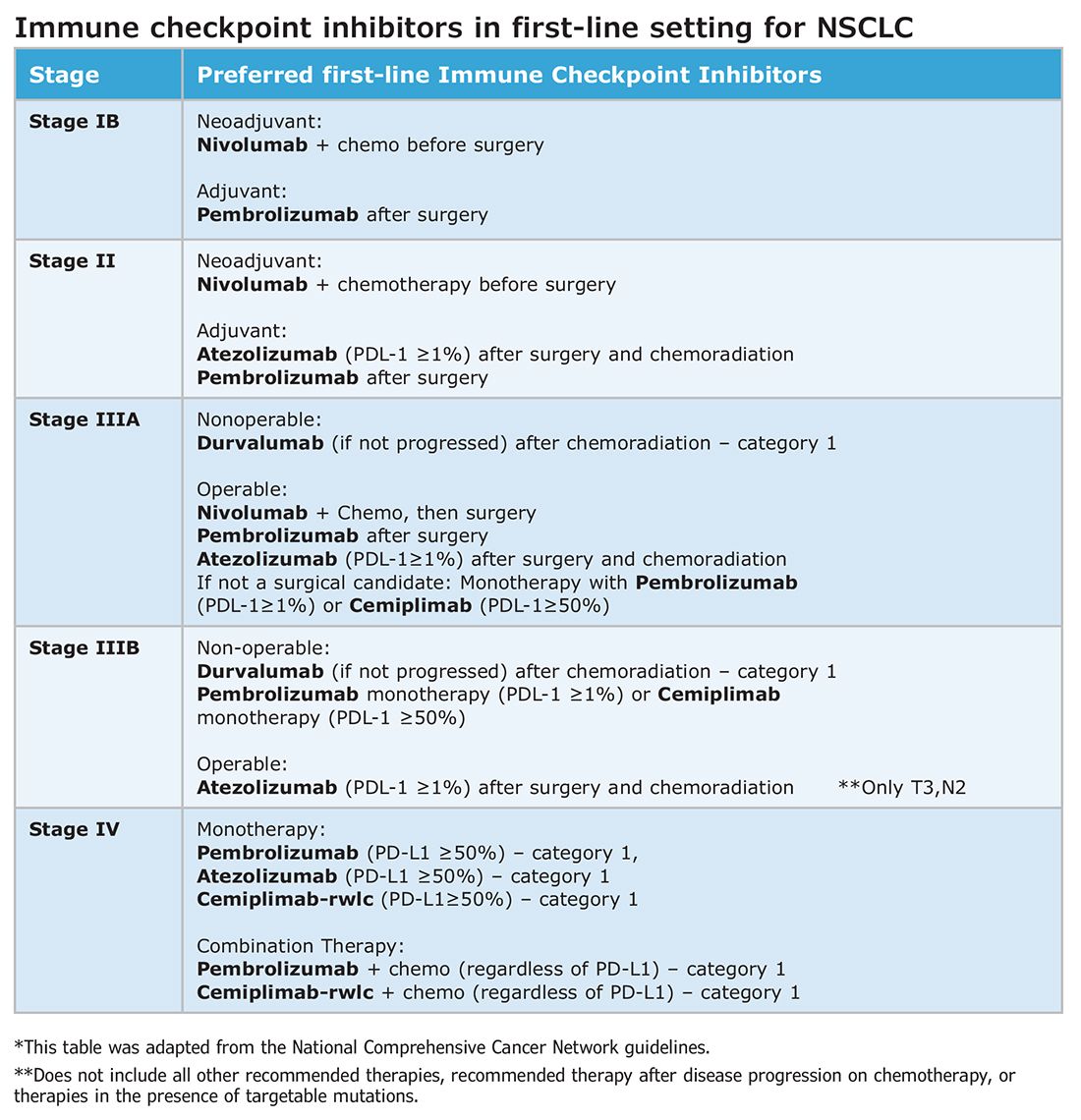

Without a doubt, immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and enhanced survival rates across the different stages of disease. High recurrence rates following complete surgical resection prompted the study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in earlier, operable stages of disease. This shift toward early application of ICI reflects the larger trend toward merging precision oncology with lung cancer staging. The resulting complexity in treatment and decision making creates systemic and logistical challenges that will require health care systems to adapt and improve.

Adjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

Prior to recent approvals for adjuvant immunotherapy, it was standard to give chemotherapy following resection of stage IB-IIIA disease, which offered a statistically nonsignificant survival gain. Recurrence in these patients is believed to be related to postsurgical micrometastasis. The utilization of alternative mechanisms to prevent recurrence is increasingly more common.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, is currently approved as first-line adjuvant treatment following chemotherapy in post-NSCLC resection patients with PD-L1 scores ≥1%. This category one recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is based on results from the IMpower010 trial, which randomized patients to Atezolizumab vs best supportive care. All were early-stage NSCLC, stage IB-IIIA, who underwent resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Statistically significant benefits were found in disease-free survival (DFS) with a trend toward overall survival.1

The PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial evaluated another PD-L1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, as adjuvant therapy. Its design largely mirrored the IMPower010 study, but it differed in that the ICI was administered with or without chemotherapy following resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Improvements in DFS were found in the overall population, leading to FDA approval for adjuvant therapy in 2023.2

These approvals require changes to the management of operable NSCLC. Until recently, it was not routine to send surgical specimens for additional testing because adjuvant treatment meant chemotherapy only. However, it is now essential that all surgically resected malignant tissue be sent for genomic sequencing and PD-L1 testing. Selecting the next form of therapy, whether it is an ICI or targeted drug therapy, depends on it.

From a surgical perspective, quality surgery with accurate nodal staging is crucial. The surgical findings can determine and identify those who are candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy. For these same reasons, it is helpful to advise surgeons preoperatively that targeted adjuvant therapy is being considered after resection.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

ICIs have also been used as neoadjuvant treatment for operable NSCLC. In 2021, the Checkmate-816 trial evaluated Nivolumab with platinum doublet chemotherapy prior to resection of stage IB-IIIa NSCLC. When compared with chemotherapy alone, there were significant improvements in EFS, MPR, and time to death or distant metastasis (TTDM) out to 3 years. At a median follow-up time of 41.4 months, only 28% in the nivolumab group had recurrence postsurgery compared with 42% in the chemotherapy-alone group.3 As a result, certain patients who are likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may additionally receive neoadjuvant immunotherapy with chemotherapy before surgical resection. In 2023, the KEYNOTE-671 study demonstrated that neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable stage II-IIIb (N2 stage) NSCLC improved EFS. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, the EFS was 62.4% in the Pembrolizumab group vs 40.6% in the placebo group (P < .001).4

Such changes in treatment options mean patients should be discussed first and simultaneous referrals to oncology and surgery should occur in early-stage NSCLC. Up-front genomic phenotyping and PD-L1 testing may assist in decision making. High PD-L1 levels correlate better with response.

When an ICI-chemotherapy combination is given up front for newly diagnosed NSCLC, there is the potential for large reductions in tumor size and lymph node burden. Although the NCCN does not recommend ICIs to induce resectability, a patient originally deemed inoperable could theoretically become a surgical candidate with neoadjuvant ICI treatment. There is also the potential for toxicity, which could increase the risk of surgery when it does occur. Such scenarios will require frequent tumor board discussions so plans can be adjusted in real time to optimize outcomes as clinical circumstances change.

Perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC

It is clear that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy can improve outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC. The combination of neoadjuvant with adjuvant immunotherapy/chemotherapy is currently being studied. Two recent phase III clinical trials, NEOTORCH and AEGAEN, have found statistical improvements in EFS and MPR with this approach.5,6 These studies have not found their way into the NCCN guidelines yet but are sure to be considered in future iterations. Once adopted, the tumor board at each institution will have more options to choose from but many more decisions to make.

References

1. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. [Published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686.]

2. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1274-1286.

3. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985.

4. Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):491-503.

5. Lu S, Zhang W, Wu L, et al. Perioperative toripalimab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: the neotorch randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(3):201-211.

6. Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al. Perioperative durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684.

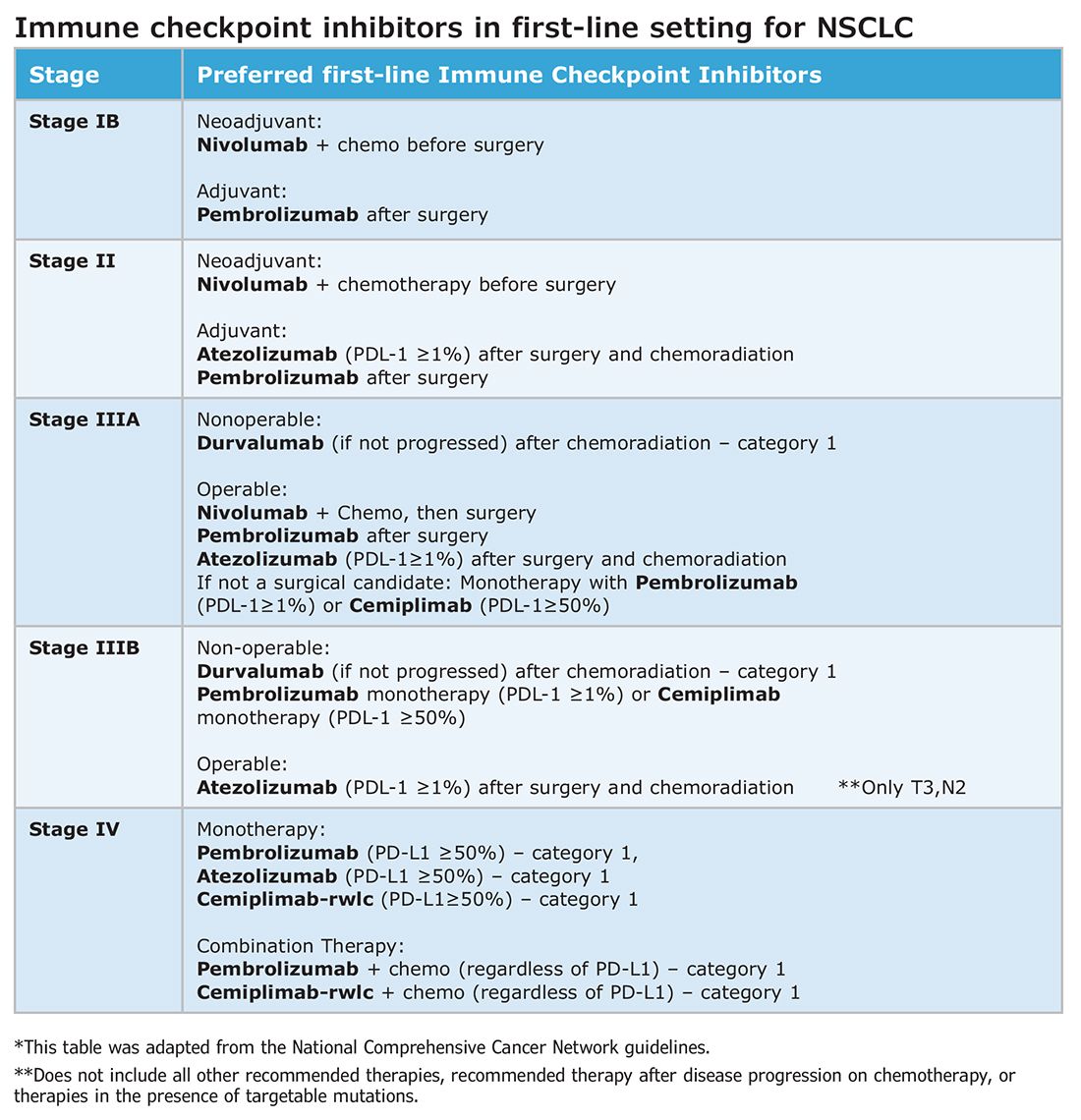

Without a doubt, immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and enhanced survival rates across the different stages of disease. High recurrence rates following complete surgical resection prompted the study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in earlier, operable stages of disease. This shift toward early application of ICI reflects the larger trend toward merging precision oncology with lung cancer staging. The resulting complexity in treatment and decision making creates systemic and logistical challenges that will require health care systems to adapt and improve.

Adjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

Prior to recent approvals for adjuvant immunotherapy, it was standard to give chemotherapy following resection of stage IB-IIIA disease, which offered a statistically nonsignificant survival gain. Recurrence in these patients is believed to be related to postsurgical micrometastasis. The utilization of alternative mechanisms to prevent recurrence is increasingly more common.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, is currently approved as first-line adjuvant treatment following chemotherapy in post-NSCLC resection patients with PD-L1 scores ≥1%. This category one recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is based on results from the IMpower010 trial, which randomized patients to Atezolizumab vs best supportive care. All were early-stage NSCLC, stage IB-IIIA, who underwent resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Statistically significant benefits were found in disease-free survival (DFS) with a trend toward overall survival.1

The PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial evaluated another PD-L1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, as adjuvant therapy. Its design largely mirrored the IMPower010 study, but it differed in that the ICI was administered with or without chemotherapy following resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Improvements in DFS were found in the overall population, leading to FDA approval for adjuvant therapy in 2023.2

These approvals require changes to the management of operable NSCLC. Until recently, it was not routine to send surgical specimens for additional testing because adjuvant treatment meant chemotherapy only. However, it is now essential that all surgically resected malignant tissue be sent for genomic sequencing and PD-L1 testing. Selecting the next form of therapy, whether it is an ICI or targeted drug therapy, depends on it.

From a surgical perspective, quality surgery with accurate nodal staging is crucial. The surgical findings can determine and identify those who are candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy. For these same reasons, it is helpful to advise surgeons preoperatively that targeted adjuvant therapy is being considered after resection.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

ICIs have also been used as neoadjuvant treatment for operable NSCLC. In 2021, the Checkmate-816 trial evaluated Nivolumab with platinum doublet chemotherapy prior to resection of stage IB-IIIa NSCLC. When compared with chemotherapy alone, there were significant improvements in EFS, MPR, and time to death or distant metastasis (TTDM) out to 3 years. At a median follow-up time of 41.4 months, only 28% in the nivolumab group had recurrence postsurgery compared with 42% in the chemotherapy-alone group.3 As a result, certain patients who are likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may additionally receive neoadjuvant immunotherapy with chemotherapy before surgical resection. In 2023, the KEYNOTE-671 study demonstrated that neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable stage II-IIIb (N2 stage) NSCLC improved EFS. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, the EFS was 62.4% in the Pembrolizumab group vs 40.6% in the placebo group (P < .001).4

Such changes in treatment options mean patients should be discussed first and simultaneous referrals to oncology and surgery should occur in early-stage NSCLC. Up-front genomic phenotyping and PD-L1 testing may assist in decision making. High PD-L1 levels correlate better with response.

When an ICI-chemotherapy combination is given up front for newly diagnosed NSCLC, there is the potential for large reductions in tumor size and lymph node burden. Although the NCCN does not recommend ICIs to induce resectability, a patient originally deemed inoperable could theoretically become a surgical candidate with neoadjuvant ICI treatment. There is also the potential for toxicity, which could increase the risk of surgery when it does occur. Such scenarios will require frequent tumor board discussions so plans can be adjusted in real time to optimize outcomes as clinical circumstances change.

Perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC

It is clear that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy can improve outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC. The combination of neoadjuvant with adjuvant immunotherapy/chemotherapy is currently being studied. Two recent phase III clinical trials, NEOTORCH and AEGAEN, have found statistical improvements in EFS and MPR with this approach.5,6 These studies have not found their way into the NCCN guidelines yet but are sure to be considered in future iterations. Once adopted, the tumor board at each institution will have more options to choose from but many more decisions to make.

References

1. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. [Published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686.]

2. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1274-1286.

3. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985.

4. Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):491-503.

5. Lu S, Zhang W, Wu L, et al. Perioperative toripalimab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: the neotorch randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(3):201-211.

6. Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al. Perioperative durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684.

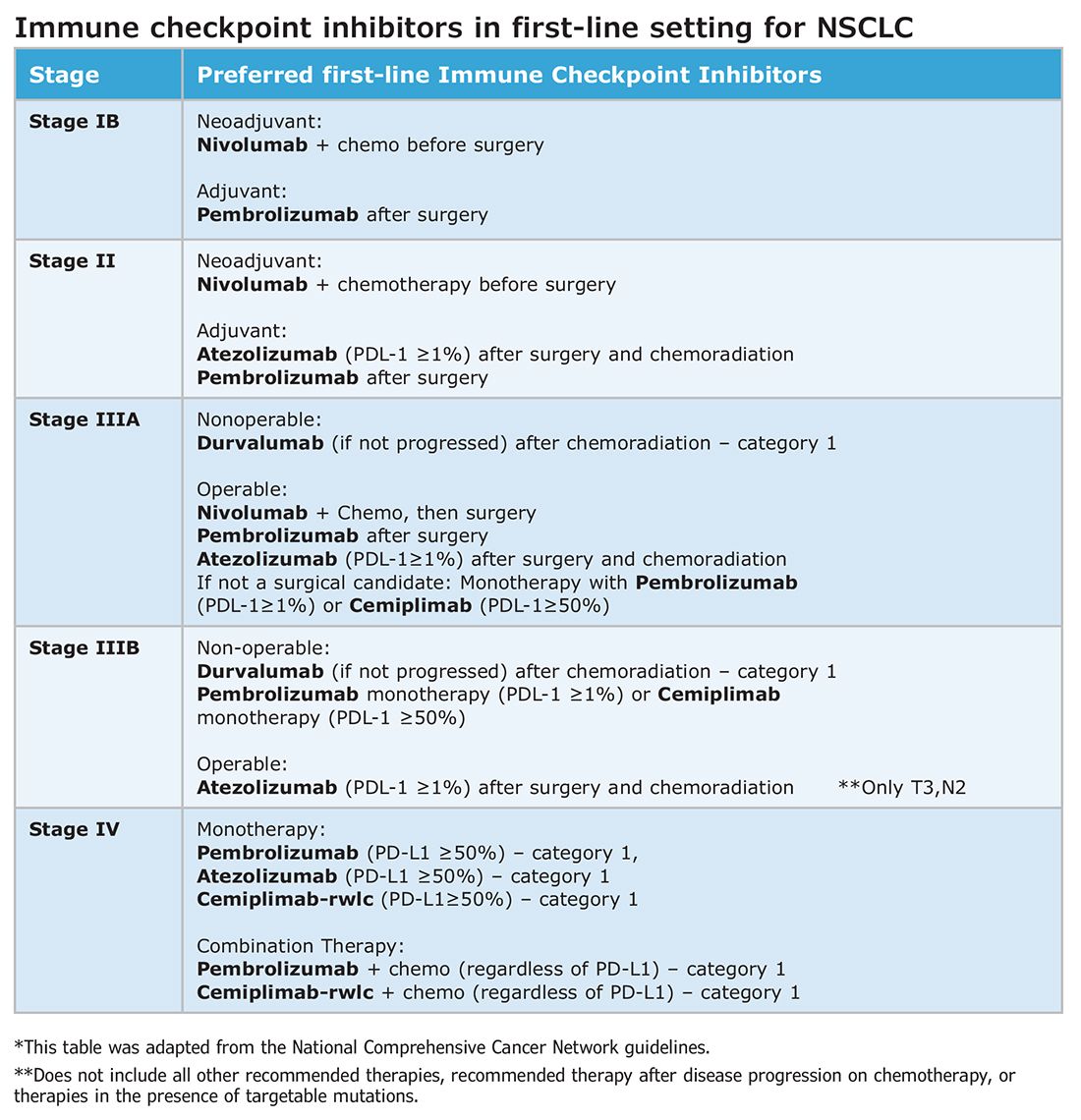

Without a doubt, immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and enhanced survival rates across the different stages of disease. High recurrence rates following complete surgical resection prompted the study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in earlier, operable stages of disease. This shift toward early application of ICI reflects the larger trend toward merging precision oncology with lung cancer staging. The resulting complexity in treatment and decision making creates systemic and logistical challenges that will require health care systems to adapt and improve.

Adjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

Prior to recent approvals for adjuvant immunotherapy, it was standard to give chemotherapy following resection of stage IB-IIIA disease, which offered a statistically nonsignificant survival gain. Recurrence in these patients is believed to be related to postsurgical micrometastasis. The utilization of alternative mechanisms to prevent recurrence is increasingly more common.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, is currently approved as first-line adjuvant treatment following chemotherapy in post-NSCLC resection patients with PD-L1 scores ≥1%. This category one recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is based on results from the IMpower010 trial, which randomized patients to Atezolizumab vs best supportive care. All were early-stage NSCLC, stage IB-IIIA, who underwent resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Statistically significant benefits were found in disease-free survival (DFS) with a trend toward overall survival.1

The PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial evaluated another PD-L1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, as adjuvant therapy. Its design largely mirrored the IMPower010 study, but it differed in that the ICI was administered with or without chemotherapy following resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Improvements in DFS were found in the overall population, leading to FDA approval for adjuvant therapy in 2023.2

These approvals require changes to the management of operable NSCLC. Until recently, it was not routine to send surgical specimens for additional testing because adjuvant treatment meant chemotherapy only. However, it is now essential that all surgically resected malignant tissue be sent for genomic sequencing and PD-L1 testing. Selecting the next form of therapy, whether it is an ICI or targeted drug therapy, depends on it.

From a surgical perspective, quality surgery with accurate nodal staging is crucial. The surgical findings can determine and identify those who are candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy. For these same reasons, it is helpful to advise surgeons preoperatively that targeted adjuvant therapy is being considered after resection.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

ICIs have also been used as neoadjuvant treatment for operable NSCLC. In 2021, the Checkmate-816 trial evaluated Nivolumab with platinum doublet chemotherapy prior to resection of stage IB-IIIa NSCLC. When compared with chemotherapy alone, there were significant improvements in EFS, MPR, and time to death or distant metastasis (TTDM) out to 3 years. At a median follow-up time of 41.4 months, only 28% in the nivolumab group had recurrence postsurgery compared with 42% in the chemotherapy-alone group.3 As a result, certain patients who are likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may additionally receive neoadjuvant immunotherapy with chemotherapy before surgical resection. In 2023, the KEYNOTE-671 study demonstrated that neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable stage II-IIIb (N2 stage) NSCLC improved EFS. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, the EFS was 62.4% in the Pembrolizumab group vs 40.6% in the placebo group (P < .001).4

Such changes in treatment options mean patients should be discussed first and simultaneous referrals to oncology and surgery should occur in early-stage NSCLC. Up-front genomic phenotyping and PD-L1 testing may assist in decision making. High PD-L1 levels correlate better with response.

When an ICI-chemotherapy combination is given up front for newly diagnosed NSCLC, there is the potential for large reductions in tumor size and lymph node burden. Although the NCCN does not recommend ICIs to induce resectability, a patient originally deemed inoperable could theoretically become a surgical candidate with neoadjuvant ICI treatment. There is also the potential for toxicity, which could increase the risk of surgery when it does occur. Such scenarios will require frequent tumor board discussions so plans can be adjusted in real time to optimize outcomes as clinical circumstances change.

Perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC

It is clear that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy can improve outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC. The combination of neoadjuvant with adjuvant immunotherapy/chemotherapy is currently being studied. Two recent phase III clinical trials, NEOTORCH and AEGAEN, have found statistical improvements in EFS and MPR with this approach.5,6 These studies have not found their way into the NCCN guidelines yet but are sure to be considered in future iterations. Once adopted, the tumor board at each institution will have more options to choose from but many more decisions to make.

References

1. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. [Published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686.]

2. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1274-1286.

3. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985.

4. Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):491-503.

5. Lu S, Zhang W, Wu L, et al. Perioperative toripalimab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: the neotorch randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(3):201-211.

6. Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al. Perioperative durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684.

Are Beta-Blockers Safe for COPD?

Everyone takes a pharmacology class in medical school that includes a lecture on beta receptors. They’re in the heart (beta-1) and lungs (beta-2), and drug compounds agonize or antagonize one or both. The professor will caution against using antagonists (beta blockade) for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) lest they further impair the patient’s irreversibly narrowed airways. Obsequious students mature into obsequious doctors, intent on “doing no harm.” For better or worse, you withhold beta-blockers from your patient with COPD and comorbid cardiac disease.

Perhaps because the pulmonologist isn’t usually the one who decides whether a beta-blocker is prescribed, I’ve been napping on this topic since training. Early in fellowship, I read an ACP Journal Club article about a Cochrane systematic review (yes, I read a review of a review) that concluded that beta-blockers are fine in patients with COPD. The summary appealed to my bias towards evidence-based medicine (EBM) supplanting physiology, medical school, and everything else. I was more apt to believe my stodgy residency attendings than the stodgy pharmacology professor. Even though COPD and cardiovascular disease share multiple risk factors, I had never reinvestigated the relationship between beta-blockers and COPD.

Turns out that while I was sleeping, the debate continued. Go figure. Just last month a prospective, observational study published in JAMA Network Open found that beta-blockers did not increase the risk for cardiovascular or respiratory events among patients with COPD being discharged after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Although this could be viewed as a triumph for EBM over physiology and a validation of my decade-plus of intellectual laziness, the results are actually pretty thin. These studies, in which patients with an indication for a therapy (a beta-blocker in this case) are analyzed by whether or not they received it, are problematic. The fanciest statistics — in this case, they used propensity scores — can’t control for residual confounding. What drove the physicians to prescribe in some cases but not others? We can only guess.

This might be okay if there hadn’t been a randomized controlled trial (RCT) published in 2019 in The New England Journal of Medicine that found that beta-blockers increase the risk for severe COPD exacerbations. In EBM, the RCT trumps all. Ironically, this trial was designed to test whether beta-blockers reduce severe COPD exacerbations. Yes, we’d come full circle. There was enough biologic plausibility to support a positive effect, or so thought the study authors and the Department of Defense (DOD) — for reasons I can’t possibly guess, the DOD funded this RCT. My pharmacology professor must be rolling over in his tenure.

The RCT did leave beta-blockers some wiggle room. The authors purposely excluded anyone with a cardiovascular indication for a beta-blocker. The intent was to ensure beneficial effects were isolated to respiratory and not cardiovascular outcomes. Of course, the reason I’m writing and you’re reading this is that COPD and cardiovascular disease co-occur at a high rate. The RCT notwithstanding, we prescribe beta-blockers to patients with COPD because they have a cardiac indication, not to reduce acute COPD exacerbations. So, it’s possible there’d be a net beta-blocker benefit in patients with COPD and comorbid heart disease.

That’s where the JAMA Network Open study comes in, but as discussed, methodologic weaknesses preclude its being the final word. That said, I think it’s unlikely we’ll see a COPD with comorbid cardiac disease RCT performed to assess whether beta-blockers provide a net benefit, unless maybe the DOD wants to fund another one of these. In the meantime, I’m calling clinical equipoise and punting. Fortunately for me, I don’t have to prescribe beta-blockers.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland, and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everyone takes a pharmacology class in medical school that includes a lecture on beta receptors. They’re in the heart (beta-1) and lungs (beta-2), and drug compounds agonize or antagonize one or both. The professor will caution against using antagonists (beta blockade) for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) lest they further impair the patient’s irreversibly narrowed airways. Obsequious students mature into obsequious doctors, intent on “doing no harm.” For better or worse, you withhold beta-blockers from your patient with COPD and comorbid cardiac disease.

Perhaps because the pulmonologist isn’t usually the one who decides whether a beta-blocker is prescribed, I’ve been napping on this topic since training. Early in fellowship, I read an ACP Journal Club article about a Cochrane systematic review (yes, I read a review of a review) that concluded that beta-blockers are fine in patients with COPD. The summary appealed to my bias towards evidence-based medicine (EBM) supplanting physiology, medical school, and everything else. I was more apt to believe my stodgy residency attendings than the stodgy pharmacology professor. Even though COPD and cardiovascular disease share multiple risk factors, I had never reinvestigated the relationship between beta-blockers and COPD.

Turns out that while I was sleeping, the debate continued. Go figure. Just last month a prospective, observational study published in JAMA Network Open found that beta-blockers did not increase the risk for cardiovascular or respiratory events among patients with COPD being discharged after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Although this could be viewed as a triumph for EBM over physiology and a validation of my decade-plus of intellectual laziness, the results are actually pretty thin. These studies, in which patients with an indication for a therapy (a beta-blocker in this case) are analyzed by whether or not they received it, are problematic. The fanciest statistics — in this case, they used propensity scores — can’t control for residual confounding. What drove the physicians to prescribe in some cases but not others? We can only guess.

This might be okay if there hadn’t been a randomized controlled trial (RCT) published in 2019 in The New England Journal of Medicine that found that beta-blockers increase the risk for severe COPD exacerbations. In EBM, the RCT trumps all. Ironically, this trial was designed to test whether beta-blockers reduce severe COPD exacerbations. Yes, we’d come full circle. There was enough biologic plausibility to support a positive effect, or so thought the study authors and the Department of Defense (DOD) — for reasons I can’t possibly guess, the DOD funded this RCT. My pharmacology professor must be rolling over in his tenure.

The RCT did leave beta-blockers some wiggle room. The authors purposely excluded anyone with a cardiovascular indication for a beta-blocker. The intent was to ensure beneficial effects were isolated to respiratory and not cardiovascular outcomes. Of course, the reason I’m writing and you’re reading this is that COPD and cardiovascular disease co-occur at a high rate. The RCT notwithstanding, we prescribe beta-blockers to patients with COPD because they have a cardiac indication, not to reduce acute COPD exacerbations. So, it’s possible there’d be a net beta-blocker benefit in patients with COPD and comorbid heart disease.

That’s where the JAMA Network Open study comes in, but as discussed, methodologic weaknesses preclude its being the final word. That said, I think it’s unlikely we’ll see a COPD with comorbid cardiac disease RCT performed to assess whether beta-blockers provide a net benefit, unless maybe the DOD wants to fund another one of these. In the meantime, I’m calling clinical equipoise and punting. Fortunately for me, I don’t have to prescribe beta-blockers.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland, and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everyone takes a pharmacology class in medical school that includes a lecture on beta receptors. They’re in the heart (beta-1) and lungs (beta-2), and drug compounds agonize or antagonize one or both. The professor will caution against using antagonists (beta blockade) for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) lest they further impair the patient’s irreversibly narrowed airways. Obsequious students mature into obsequious doctors, intent on “doing no harm.” For better or worse, you withhold beta-blockers from your patient with COPD and comorbid cardiac disease.

Perhaps because the pulmonologist isn’t usually the one who decides whether a beta-blocker is prescribed, I’ve been napping on this topic since training. Early in fellowship, I read an ACP Journal Club article about a Cochrane systematic review (yes, I read a review of a review) that concluded that beta-blockers are fine in patients with COPD. The summary appealed to my bias towards evidence-based medicine (EBM) supplanting physiology, medical school, and everything else. I was more apt to believe my stodgy residency attendings than the stodgy pharmacology professor. Even though COPD and cardiovascular disease share multiple risk factors, I had never reinvestigated the relationship between beta-blockers and COPD.

Turns out that while I was sleeping, the debate continued. Go figure. Just last month a prospective, observational study published in JAMA Network Open found that beta-blockers did not increase the risk for cardiovascular or respiratory events among patients with COPD being discharged after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Although this could be viewed as a triumph for EBM over physiology and a validation of my decade-plus of intellectual laziness, the results are actually pretty thin. These studies, in which patients with an indication for a therapy (a beta-blocker in this case) are analyzed by whether or not they received it, are problematic. The fanciest statistics — in this case, they used propensity scores — can’t control for residual confounding. What drove the physicians to prescribe in some cases but not others? We can only guess.

This might be okay if there hadn’t been a randomized controlled trial (RCT) published in 2019 in The New England Journal of Medicine that found that beta-blockers increase the risk for severe COPD exacerbations. In EBM, the RCT trumps all. Ironically, this trial was designed to test whether beta-blockers reduce severe COPD exacerbations. Yes, we’d come full circle. There was enough biologic plausibility to support a positive effect, or so thought the study authors and the Department of Defense (DOD) — for reasons I can’t possibly guess, the DOD funded this RCT. My pharmacology professor must be rolling over in his tenure.

The RCT did leave beta-blockers some wiggle room. The authors purposely excluded anyone with a cardiovascular indication for a beta-blocker. The intent was to ensure beneficial effects were isolated to respiratory and not cardiovascular outcomes. Of course, the reason I’m writing and you’re reading this is that COPD and cardiovascular disease co-occur at a high rate. The RCT notwithstanding, we prescribe beta-blockers to patients with COPD because they have a cardiac indication, not to reduce acute COPD exacerbations. So, it’s possible there’d be a net beta-blocker benefit in patients with COPD and comorbid heart disease.

That’s where the JAMA Network Open study comes in, but as discussed, methodologic weaknesses preclude its being the final word. That said, I think it’s unlikely we’ll see a COPD with comorbid cardiac disease RCT performed to assess whether beta-blockers provide a net benefit, unless maybe the DOD wants to fund another one of these. In the meantime, I’m calling clinical equipoise and punting. Fortunately for me, I don’t have to prescribe beta-blockers.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland, and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Military burn pits: Their evidence and implications for respiratory health

Military service is a hazard-ridden profession. It’s easy to recognize the direct dangers from warfighting, such as gunfire and explosions, but the risks from environmental, chemical, and other occupational exposures can be harder to see.

Combustion-based waste management systems, otherwise known as “burn pits,” were used in deployed environments by the US military from the 1990s to the early 2010s. These burn pits were commonly used to eliminate plastics, electronics, munitions, metals, wood, chemicals, and even human waste. At the height of the recent conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other southwest Asia locations, more than 70% of military installations employed at least one, and nearly 4 million service members were exposed to some degree to their emissions.

Reports of burn pits being related to organic disease have garnered widespread media attention. Initially, this came through anecdotal reports of post-deployment respiratory symptoms. Over time, the conditions attributed to burn pits expanded to include newly diagnosed respiratory diseases and malignancies.

Ultimately, Congress passed the 2022 Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxins (PACT) Act, presumptively linking more than 20 diagnoses to burn pits. The PACT Act provides countless veterans access to low-cost or free medical care for their respective conditions.

What do we know about burn pits and deployment-related respiratory disease?

Data from the Millennium Cohort Study noted an approximately 40% increase in respiratory symptoms among individuals returning from deployment but no increase in the frequency of diagnosed respiratory diseases.1 This study and others definitively established a temporal relationship between deployment and respiratory symptoms. Soon after, a retrospective, observational study of service members with post-deployment respiratory symptoms found a high prevalence of constrictive bronchiolitis (CB) identified by lung biopsy.2 Patients in this group reported exposure to burn pits and a sulfur mine fire in the Mosul area while deployed. Most had normal imaging and pulmonary function testing before biopsy, confounding the clinical significance of the CB finding. The publication of this report led to increased investigation of respiratory function during and after deployment.

In a series of prospective studies that included full pulmonary function testing, impulse oscillometry, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, bronchoscopy, and, occasionally, lung biopsy to evaluate post-deployment dyspnea, only a small minority received a diagnosis of clinically significant lung disease.3,4 Additionally, when comparing spirometry and impulse oscillometry results from before and after deployment, no decline in lung function was observed in a population of service members reporting regular burn pit exposure.5 These studies suggest that at the population level, deployment does not lead to abnormalities in the structure and function of the respiratory system.

The National Academies of Sciences published two separate reviews of burn pit exposure and outcomes in 2011 and 2020.6,7 They found insufficient evidence to support a causal relationship between burn pit exposure and pulmonary disease. They highlighted studies on the composition of emissions from the area surrounding the largest military burn pit in Iraq. Levels of particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were elevated when compared with those of a typical American city but were similar to the pollution levels seen in the region at the time. Given these findings, they suggested ambient air pollution may have contributed more to clinically significant disease than burn pit emissions.

How do we interpret this mixed data?

At the population level, we have yet to find conclusive data directly linking burn pit exposure to the development of any respiratory disease. Does this mean that burn pits are not harmful?

Not necessarily. Research on outcomes related to burn pit exposure is challenging given the heterogeneity in exposure volume. Much of the research is retrospective and subject to recall bias. Relationships may be distorted, and the precision of reported symptoms and exposure levels is altered. Given these challenges, it’s unsurprising that evidence of causality has yet to be proven. In addition, some portion of service members has been diagnosed with respiratory disease that could be related to burn pit exposure.

What is now indisputable is that deployment to southwest Asia leads to an increase in respiratory complaints. Whether veteran respiratory symptoms are due to burn pits, ambient pollution, environmental particulate matter, or dust storms is less clinically relevant. These symptoms require attention, investigation, and management.

What does this mean for the future medical care of service members and veterans?

Many veterans with post-deployment respiratory symptoms undergo extensive evaluations without obtaining a definitive diagnosis. A recent consensus statement on deployment-related respiratory symptoms provides a framework for evaluation in such cases.8 In keeping with that statement, we recommend veterans be referred to centers with expertise in this field, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or military health centers, when deployment-related respiratory symptoms are reported. When the evaluation does not lead to a treatable diagnosis, these centers can provide multidisciplinary care to address the symptoms of dyspnea, cough, fatigue, and exercise intolerance to improve functional status.

Despite uncertainty in the evidence or challenges in diagnosis, both the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA remain fully committed to addressing the health concerns of service members and veterans. Notably, the VA has already screened more than 5 million veterans for toxic military exposures in accordance with the PACT Act and is providing ongoing screening and care for veterans with post-deployment respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, the DoD and VA have dedicated large portions of their research budgets to investigating the impacts of exposures during military service and optimizing the care of those with respiratory symptoms. With these commitments to patient care and research, our veterans’ respiratory health can now be optimized, and future risks can be mitigated.

Dr. Haynes is Fellow, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Uniformed Services University. Dr. Nations is Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Associate Professor of Medicine, Uniformed Services University.

References

1. Smith B, Wong CA, Smith TC, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD; Margaret A. K. Ryan for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1433-1442. Preprint. Posted online October 22, 2009. PMID: 19850627. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp287

2. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):222-230. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1749. PMID: 21774710; PMCID: PMC3296566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

3. Morris MJ, Dodson DW, Lucero PF, et al. Study of active duty military for pulmonary disease related to environmental deployment exposures (STAMPEDE). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(1):77-84. PMID: 24922562. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0372OC

4. Morris MJ, Walter RJ, McCann ET, et al. Clinical evaluation of deployed military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms: study of active duty military for pulmonary disease related to environmental deployment exposures (STAMPEDE) III. Chest. 2020;157(6):1559-1567. Preprint. Posted online February 1, 2020. PMID: 32017933. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.024

5. Morris MJ, Skabelund AJ, Rawlins FA 3rd, Gallup RA, Aden JK, Holley AB. Study of active duty military personnel for environmental deployment exposures: pre- and post-deployment spirometry (STAMPEDE II). Respir Care. 2019;64(5):536-544. Preprint. Posted online January 8, 2019.PMID: 30622173. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06396

6. Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. The National Academies Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13209

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. The National Academies Press; 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25837

8. Falvo MJ, Sotolongo AM, Osterholzer JJ, et al. Consensus statements on deployment-related respiratory disease, inclusive of constrictive bronchiolitis: a modified Delphi study. Chest. 2023;163(3):599-609. Preprint. Posted November 4, 2022. PMID: 36343686; PMCID: PMC10154857. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.10.031

Military service is a hazard-ridden profession. It’s easy to recognize the direct dangers from warfighting, such as gunfire and explosions, but the risks from environmental, chemical, and other occupational exposures can be harder to see.

Combustion-based waste management systems, otherwise known as “burn pits,” were used in deployed environments by the US military from the 1990s to the early 2010s. These burn pits were commonly used to eliminate plastics, electronics, munitions, metals, wood, chemicals, and even human waste. At the height of the recent conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other southwest Asia locations, more than 70% of military installations employed at least one, and nearly 4 million service members were exposed to some degree to their emissions.

Reports of burn pits being related to organic disease have garnered widespread media attention. Initially, this came through anecdotal reports of post-deployment respiratory symptoms. Over time, the conditions attributed to burn pits expanded to include newly diagnosed respiratory diseases and malignancies.

Ultimately, Congress passed the 2022 Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxins (PACT) Act, presumptively linking more than 20 diagnoses to burn pits. The PACT Act provides countless veterans access to low-cost or free medical care for their respective conditions.

What do we know about burn pits and deployment-related respiratory disease?

Data from the Millennium Cohort Study noted an approximately 40% increase in respiratory symptoms among individuals returning from deployment but no increase in the frequency of diagnosed respiratory diseases.1 This study and others definitively established a temporal relationship between deployment and respiratory symptoms. Soon after, a retrospective, observational study of service members with post-deployment respiratory symptoms found a high prevalence of constrictive bronchiolitis (CB) identified by lung biopsy.2 Patients in this group reported exposure to burn pits and a sulfur mine fire in the Mosul area while deployed. Most had normal imaging and pulmonary function testing before biopsy, confounding the clinical significance of the CB finding. The publication of this report led to increased investigation of respiratory function during and after deployment.

In a series of prospective studies that included full pulmonary function testing, impulse oscillometry, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, bronchoscopy, and, occasionally, lung biopsy to evaluate post-deployment dyspnea, only a small minority received a diagnosis of clinically significant lung disease.3,4 Additionally, when comparing spirometry and impulse oscillometry results from before and after deployment, no decline in lung function was observed in a population of service members reporting regular burn pit exposure.5 These studies suggest that at the population level, deployment does not lead to abnormalities in the structure and function of the respiratory system.

The National Academies of Sciences published two separate reviews of burn pit exposure and outcomes in 2011 and 2020.6,7 They found insufficient evidence to support a causal relationship between burn pit exposure and pulmonary disease. They highlighted studies on the composition of emissions from the area surrounding the largest military burn pit in Iraq. Levels of particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were elevated when compared with those of a typical American city but were similar to the pollution levels seen in the region at the time. Given these findings, they suggested ambient air pollution may have contributed more to clinically significant disease than burn pit emissions.

How do we interpret this mixed data?

At the population level, we have yet to find conclusive data directly linking burn pit exposure to the development of any respiratory disease. Does this mean that burn pits are not harmful?

Not necessarily. Research on outcomes related to burn pit exposure is challenging given the heterogeneity in exposure volume. Much of the research is retrospective and subject to recall bias. Relationships may be distorted, and the precision of reported symptoms and exposure levels is altered. Given these challenges, it’s unsurprising that evidence of causality has yet to be proven. In addition, some portion of service members has been diagnosed with respiratory disease that could be related to burn pit exposure.

What is now indisputable is that deployment to southwest Asia leads to an increase in respiratory complaints. Whether veteran respiratory symptoms are due to burn pits, ambient pollution, environmental particulate matter, or dust storms is less clinically relevant. These symptoms require attention, investigation, and management.

What does this mean for the future medical care of service members and veterans?

Many veterans with post-deployment respiratory symptoms undergo extensive evaluations without obtaining a definitive diagnosis. A recent consensus statement on deployment-related respiratory symptoms provides a framework for evaluation in such cases.8 In keeping with that statement, we recommend veterans be referred to centers with expertise in this field, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or military health centers, when deployment-related respiratory symptoms are reported. When the evaluation does not lead to a treatable diagnosis, these centers can provide multidisciplinary care to address the symptoms of dyspnea, cough, fatigue, and exercise intolerance to improve functional status.

Despite uncertainty in the evidence or challenges in diagnosis, both the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA remain fully committed to addressing the health concerns of service members and veterans. Notably, the VA has already screened more than 5 million veterans for toxic military exposures in accordance with the PACT Act and is providing ongoing screening and care for veterans with post-deployment respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, the DoD and VA have dedicated large portions of their research budgets to investigating the impacts of exposures during military service and optimizing the care of those with respiratory symptoms. With these commitments to patient care and research, our veterans’ respiratory health can now be optimized, and future risks can be mitigated.

Dr. Haynes is Fellow, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Uniformed Services University. Dr. Nations is Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Washington DC VA Medical Center, Associate Professor of Medicine, Uniformed Services University.

References

1. Smith B, Wong CA, Smith TC, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD; Margaret A. K. Ryan for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1433-1442. Preprint. Posted online October 22, 2009. PMID: 19850627. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp287

2. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):222-230. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1749. PMID: 21774710; PMCID: PMC3296566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

3. Morris MJ, Dodson DW, Lucero PF, et al. Study of active duty military for pulmonary disease related to environmental deployment exposures (STAMPEDE). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(1):77-84. PMID: 24922562. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0372OC

4. Morris MJ, Walter RJ, McCann ET, et al. Clinical evaluation of deployed military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms: study of active duty military for pulmonary disease related to environmental deployment exposures (STAMPEDE) III. Chest. 2020;157(6):1559-1567. Preprint. Posted online February 1, 2020. PMID: 32017933. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.024

5. Morris MJ, Skabelund AJ, Rawlins FA 3rd, Gallup RA, Aden JK, Holley AB. Study of active duty military personnel for environmental deployment exposures: pre- and post-deployment spirometry (STAMPEDE II). Respir Care. 2019;64(5):536-544. Preprint. Posted online January 8, 2019.PMID: 30622173. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06396

6. Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. The National Academies Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13209

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. The National Academies Press; 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25837

8. Falvo MJ, Sotolongo AM, Osterholzer JJ, et al. Consensus statements on deployment-related respiratory disease, inclusive of constrictive bronchiolitis: a modified Delphi study. Chest. 2023;163(3):599-609. Preprint. Posted November 4, 2022. PMID: 36343686; PMCID: PMC10154857. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.10.031

Military service is a hazard-ridden profession. It’s easy to recognize the direct dangers from warfighting, such as gunfire and explosions, but the risks from environmental, chemical, and other occupational exposures can be harder to see.

Combustion-based waste management systems, otherwise known as “burn pits,” were used in deployed environments by the US military from the 1990s to the early 2010s. These burn pits were commonly used to eliminate plastics, electronics, munitions, metals, wood, chemicals, and even human waste. At the height of the recent conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other southwest Asia locations, more than 70% of military installations employed at least one, and nearly 4 million service members were exposed to some degree to their emissions.

Reports of burn pits being related to organic disease have garnered widespread media attention. Initially, this came through anecdotal reports of post-deployment respiratory symptoms. Over time, the conditions attributed to burn pits expanded to include newly diagnosed respiratory diseases and malignancies.

Ultimately, Congress passed the 2022 Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxins (PACT) Act, presumptively linking more than 20 diagnoses to burn pits. The PACT Act provides countless veterans access to low-cost or free medical care for their respective conditions.

What do we know about burn pits and deployment-related respiratory disease?