User login

Finding a new approach to difficult diagnoses

Reducing – or managing – uncertainty

Beyond its clinical objective, the Socrates Project also seeks to further the discovery of previously unrecognized disease processes.

Many patients do not have a diagnosis that explains their signs and symptoms, despite a thorough evaluation, said Benjamin Singer, MD, assistant professor of pulmonology and critical care at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. To address that problem, he and his colleagues launched the Socrates Project. The service is intended for difficult diagnoses and is based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.

“We began the Socrates Project to assist physicians caring for patients who lack a specific diagnosis. In creating this service, we have found ourselves to be doctors for doctors – formalizing the curbside consultation,” Dr. Singer said.

Northwestern Medicine launched the Socrates Project in 2015. It’s a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. “Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce – or at least manage – diagnostic uncertainty,” they write. “Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations.”

Hospitalists at other institutions may be interested in starting a similar type of service at their own institution or collaborating with institutions who offer this type of service, Dr. Singer said.

At Northwestern Medicine, they are at work on the project’s next steps. “We are working to generate systematic data about our practice, particularly the types of referrals and outcomes,” he said.

Reference

1. Singer BD, et al. The Socrates Project for Difficult Diagnosis at Northwestern Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020 February;15(2):116-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.3335.

Reducing – or managing – uncertainty

Reducing – or managing – uncertainty

Beyond its clinical objective, the Socrates Project also seeks to further the discovery of previously unrecognized disease processes.

Many patients do not have a diagnosis that explains their signs and symptoms, despite a thorough evaluation, said Benjamin Singer, MD, assistant professor of pulmonology and critical care at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. To address that problem, he and his colleagues launched the Socrates Project. The service is intended for difficult diagnoses and is based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.

“We began the Socrates Project to assist physicians caring for patients who lack a specific diagnosis. In creating this service, we have found ourselves to be doctors for doctors – formalizing the curbside consultation,” Dr. Singer said.

Northwestern Medicine launched the Socrates Project in 2015. It’s a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. “Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce – or at least manage – diagnostic uncertainty,” they write. “Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations.”

Hospitalists at other institutions may be interested in starting a similar type of service at their own institution or collaborating with institutions who offer this type of service, Dr. Singer said.

At Northwestern Medicine, they are at work on the project’s next steps. “We are working to generate systematic data about our practice, particularly the types of referrals and outcomes,” he said.

Reference

1. Singer BD, et al. The Socrates Project for Difficult Diagnosis at Northwestern Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020 February;15(2):116-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.3335.

Beyond its clinical objective, the Socrates Project also seeks to further the discovery of previously unrecognized disease processes.

Many patients do not have a diagnosis that explains their signs and symptoms, despite a thorough evaluation, said Benjamin Singer, MD, assistant professor of pulmonology and critical care at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. To address that problem, he and his colleagues launched the Socrates Project. The service is intended for difficult diagnoses and is based on Socratic principles, particularly the role of iterative hypothesis testing in the process of diagnosis.

“We began the Socrates Project to assist physicians caring for patients who lack a specific diagnosis. In creating this service, we have found ourselves to be doctors for doctors – formalizing the curbside consultation,” Dr. Singer said.

Northwestern Medicine launched the Socrates Project in 2015. It’s a physician-to-physician consultation service that assists doctors working to diagnose conditions that have so far eluded detection. “Our service’s goal is to improve patient care by providing an opinion to the referring physician on diagnostic possibilities for a particular case and ideas to reduce – or at least manage – diagnostic uncertainty,” they write. “Our service model is similar to a tumor board, which exists as an interdisciplinary group operating in parallel to the clinical services, to provide consensus-based recommendations.”

Hospitalists at other institutions may be interested in starting a similar type of service at their own institution or collaborating with institutions who offer this type of service, Dr. Singer said.

At Northwestern Medicine, they are at work on the project’s next steps. “We are working to generate systematic data about our practice, particularly the types of referrals and outcomes,” he said.

Reference

1. Singer BD, et al. The Socrates Project for Difficult Diagnosis at Northwestern Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020 February;15(2):116-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.3335.

Is COVID-19 accelerating progress toward high-value care?

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

New updates for Choosing Wisely in hospitalized patients with infection

Background: A new update to the Choosing Wisely Campaign was released September 2019.

Study design: Expert consensus recommendations from the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

Synopsis: Eleven of the 30 Choosing Wisely recommendations directly affect hospital medicine. Half of these recommendations are related to infectious diseases. Highlights include:

- Not routinely using broad respiratory viral testing and instead using more targeted approaches to respiratory pathogen tests (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A/B, or group A pharyngitis) unless the results will lead to changes to or discontinuations of antimicrobial therapy or isolation.

- Not routinely testing for community gastrointestinal pathogens in patients that develop diarrhea 3 days after hospitalization and to primarily test for Clostridiodes difficile in these patients, unless they are immunocompromised or older adults.

- Not checking procalcitonin unless a specific evidence-based guideline is used for antibiotic stewardship, as it is often used incorrectly without benefit to the patient.

- Not ordering serology for Helicobacter pylori and instead ordering the stool antigen or breath test to test for active infection given higher sensitivity and specificity.

- Not repeating antibody tests for patients with history of hepatitis C and instead ordering a viral load if there is concern for reinfection.

Bottom line: Only order infectious disease tests that will guide changes in clinical management.

Citation: ASCP Effective Test Utilization Steering Committee. Thirty things patients and physicians should question. 2019 Sep 9. Choosingwisely.org.

Dr. Blount is clinical instructor of medicine, hospital medicine, at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Background: A new update to the Choosing Wisely Campaign was released September 2019.

Study design: Expert consensus recommendations from the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

Synopsis: Eleven of the 30 Choosing Wisely recommendations directly affect hospital medicine. Half of these recommendations are related to infectious diseases. Highlights include:

- Not routinely using broad respiratory viral testing and instead using more targeted approaches to respiratory pathogen tests (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A/B, or group A pharyngitis) unless the results will lead to changes to or discontinuations of antimicrobial therapy or isolation.

- Not routinely testing for community gastrointestinal pathogens in patients that develop diarrhea 3 days after hospitalization and to primarily test for Clostridiodes difficile in these patients, unless they are immunocompromised or older adults.

- Not checking procalcitonin unless a specific evidence-based guideline is used for antibiotic stewardship, as it is often used incorrectly without benefit to the patient.

- Not ordering serology for Helicobacter pylori and instead ordering the stool antigen or breath test to test for active infection given higher sensitivity and specificity.

- Not repeating antibody tests for patients with history of hepatitis C and instead ordering a viral load if there is concern for reinfection.

Bottom line: Only order infectious disease tests that will guide changes in clinical management.

Citation: ASCP Effective Test Utilization Steering Committee. Thirty things patients and physicians should question. 2019 Sep 9. Choosingwisely.org.

Dr. Blount is clinical instructor of medicine, hospital medicine, at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Background: A new update to the Choosing Wisely Campaign was released September 2019.

Study design: Expert consensus recommendations from the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

Synopsis: Eleven of the 30 Choosing Wisely recommendations directly affect hospital medicine. Half of these recommendations are related to infectious diseases. Highlights include:

- Not routinely using broad respiratory viral testing and instead using more targeted approaches to respiratory pathogen tests (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A/B, or group A pharyngitis) unless the results will lead to changes to or discontinuations of antimicrobial therapy or isolation.

- Not routinely testing for community gastrointestinal pathogens in patients that develop diarrhea 3 days after hospitalization and to primarily test for Clostridiodes difficile in these patients, unless they are immunocompromised or older adults.

- Not checking procalcitonin unless a specific evidence-based guideline is used for antibiotic stewardship, as it is often used incorrectly without benefit to the patient.

- Not ordering serology for Helicobacter pylori and instead ordering the stool antigen or breath test to test for active infection given higher sensitivity and specificity.

- Not repeating antibody tests for patients with history of hepatitis C and instead ordering a viral load if there is concern for reinfection.

Bottom line: Only order infectious disease tests that will guide changes in clinical management.

Citation: ASCP Effective Test Utilization Steering Committee. Thirty things patients and physicians should question. 2019 Sep 9. Choosingwisely.org.

Dr. Blount is clinical instructor of medicine, hospital medicine, at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Think twice before intensifying BP regimen in older hospitalized patients

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.

Patients discharged with regimen intensification were more likely to be readmitted (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42; number needed to harm = 27), experience a medication-related serious adverse event (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.06-1.88; NNH = 63), and have a cardiovascular event (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.13-2.4) within 30 days of discharge. At 1 year, no significant difference in mortality, cardiovascular events, or systolic BP were noted between the two groups.

A subgroup analysis of patients with poorly controlled blood pressure as outpatients (defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg) who had their anti-hypertensive medications intensified did not show significant difference in 30-day readmission, severe adverse events, or cardiovascular events.

Limitations of the study include observational design and majority male sex (97.5%) of the study population.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive regimen among older adults hospitalized for noncardiac conditions with well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient can potentially cause harm.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007.

Dr. Zarookian is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.

Patients discharged with regimen intensification were more likely to be readmitted (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42; number needed to harm = 27), experience a medication-related serious adverse event (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.06-1.88; NNH = 63), and have a cardiovascular event (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.13-2.4) within 30 days of discharge. At 1 year, no significant difference in mortality, cardiovascular events, or systolic BP were noted between the two groups.

A subgroup analysis of patients with poorly controlled blood pressure as outpatients (defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg) who had their anti-hypertensive medications intensified did not show significant difference in 30-day readmission, severe adverse events, or cardiovascular events.

Limitations of the study include observational design and majority male sex (97.5%) of the study population.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive regimen among older adults hospitalized for noncardiac conditions with well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient can potentially cause harm.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007.

Dr. Zarookian is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.

Patients discharged with regimen intensification were more likely to be readmitted (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42; number needed to harm = 27), experience a medication-related serious adverse event (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.06-1.88; NNH = 63), and have a cardiovascular event (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.13-2.4) within 30 days of discharge. At 1 year, no significant difference in mortality, cardiovascular events, or systolic BP were noted between the two groups.

A subgroup analysis of patients with poorly controlled blood pressure as outpatients (defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg) who had their anti-hypertensive medications intensified did not show significant difference in 30-day readmission, severe adverse events, or cardiovascular events.

Limitations of the study include observational design and majority male sex (97.5%) of the study population.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive regimen among older adults hospitalized for noncardiac conditions with well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient can potentially cause harm.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007.

Dr. Zarookian is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Finding meaning in ‘Lean’?

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

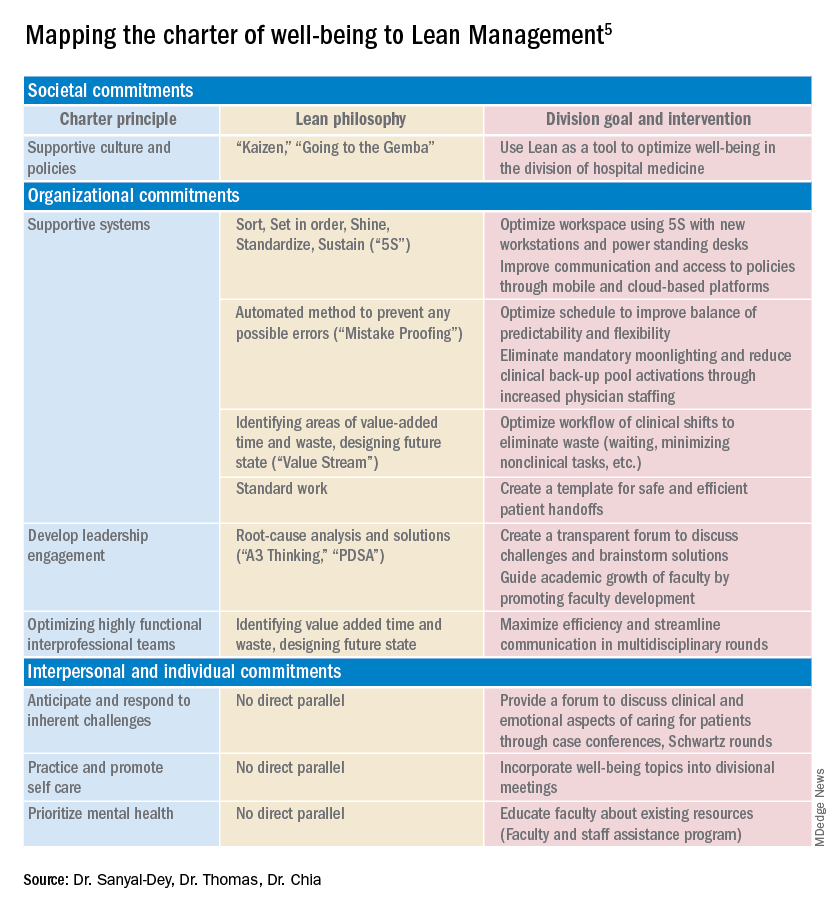

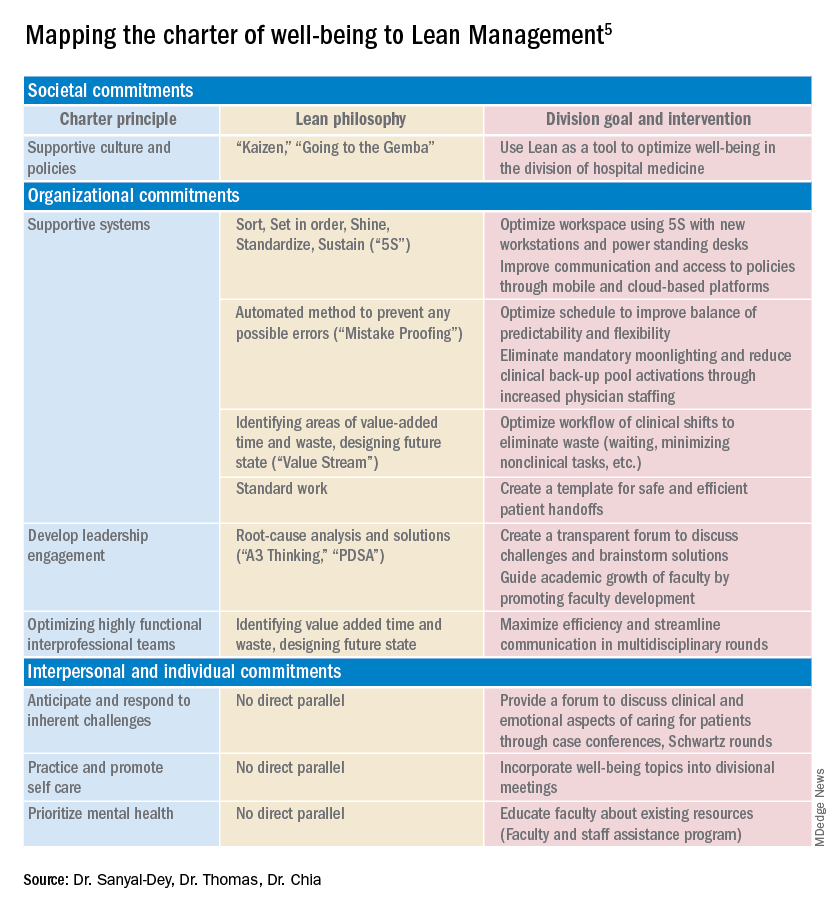

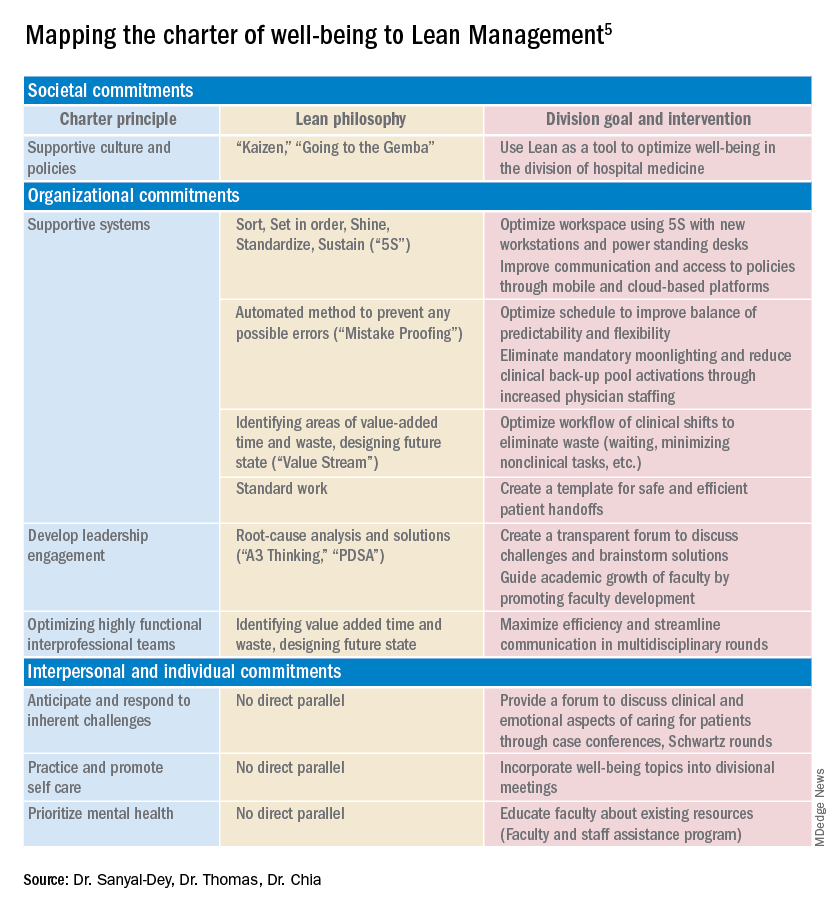

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.