The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B 60 mg/d and flucytosine 500 mg every 6 hours for 3 weeks. Oral fluconazole 400 mg every morning was also given (intended duration, 6 mo). Given that diabetes was newly diagnosed, the patient was treated with metformin; his capillary blood glucose level remained stable during his inpatient stay.

Four débridements of the dorsal hand wound were performed—the first on day of admission and the other 3 on hospitalization days 3, 7, and 18 (Figure 4). Subsequent wound resurfacing with a split skin graft harvested from the forearm was performed on hospitalization day 22. After surgery, the hand was dressed with a bulky cotton dressing. Five days after the patient was discharged, during review in the outpatient clinic, the skin graft was noted to be taking well. The patient did not attend postoperative physical therapy. He was maintained on metformin and given a follow-up clinic appointment for his diabetes. Four months after surgery, the wound was completely healed, and normal functional use of the hand recovered.

Discussion

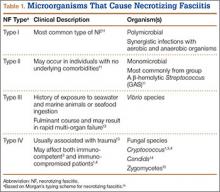

NF is a severe soft-tissue infection with potential for rapid progression. Surgical débridement should be performed urgently to reduce the chance of morbidity and mortality.11 The initial classification by Giuliano and colleagues12 was based on bacteriology and included type I (anaerobic species in combination with a facultative species) and type II (monomicrobial usually involving group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus). This classification was modified by Morgan13 to include gram-negative organisms as well as fungal organisms (Table 1).

Fungal NF is rare, with Candida, Apophysomyces, and Cryptococcus described in the literature.1,14,15 Fungal infections tend to occur in immunocompromised patients; risk factors are steroid immunosuppression, poorly controlled diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease.16 Some zygomycetes may also affect immunocompetent patients.15

C gattii is an encapsulated yeast organism that is genetically and biochemically distinct from C neoformans. It is endemic to tropical parts of Africa and Australia. Its main environmental sources are eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus tereticornis) and decaying hollows in living trees.17 In addition, there have been reports of isolation of C gattii from insect frass,18 which would make infection by an insect bite a possible transmission route. Worldwide distribution of this pathogen has increased recently, with outbreaks noted on Vancouver Island and in areas in Canada and the northwest United States.7

The true incidence of NF secondary to C gattii is difficult to determine. C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, and pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans may instead have been caused by C gattii. Misidentification has been compounded by the fact that the tests required for accurate diagnosis of C gattii infection may not be readily available in many clinical microbiology laboratories. Cryptococcus can be identified with various methods, including direct microscopy, culturing of tissue or fluid samples, and measurement of cryptococcal serum antigen. However, tests such as specific culture media, mass spectrometry, and molecular typing studies are required to determine cryptococcal species. L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar is a medium that is often used to differentiate C gattii from C neoformans because of the ability of C gattii to produce a blue appearance.6 Modern techniques, such as MALDI-TOF MS, have also been used to successfully distinguish between C gattii and C neoformans.9 MALDI-TOF MS identifies species on the basis of characteristic protein spectra extracted from whole cells. Using commercial and supplemental reference libraries, the system compares signal matches in the reference spectrum with Cryptococcus entries in the library—allowing rapid and accurate identification of cryptococcal species. However, this diagnostic method is limited by availability of adequate Cryptococcus entries in the reference library and by the high cost of acquiring the machine.

Serotyping is based on the antigenic property of the capsule and was once used to differentiate C neoformans into its 3 main varieties: var. neoformans, var. grubii, var. gattii. However, when it was realized that the antigenic property of the strain can be unstable and that there are hybrids containing more than 1 serotype, serotyping was abandoned as a species-differentiation test.6 The current gold standard for species differentiation is molecular genotyping. Molecular genotyping studies can confirm the diagnosis of C gattii infection and allow differentiation of C gattii into its 4 main molecular types: VGI, VGII, VGIII, VGIV. Using methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, molecular typing allows for specific epidemiology charting of C gattii genotypes.7

Although the transmission route for cryptococcal infection is mainly respiratory, direct inoculation has been reported as well.19 Cutaneous lesions, which occur in 5% to 20% of cryptococcal infections, often present in the head and neck.2,20,21 Primary cutaneous infections from cryptococcosis are rare, and cutaneous manifestations are often a sign of disseminated disease. Disseminated disease is defined as the involvement of 2 or more noncontiguous sites or evidence of high fungal burden based on cryptococcal antigen titer of more than 1:512.12 It is important to exclude disseminated disease in all cases of cryptococcosis, as it may be fatal.20 The neural and pulmonary systems should be screened.22 Cellulitis from cryptococcosis is almost always limited to immunocompromised patients, though there are reports of crytococcal cutaneous disease in immunocompetent patients.3,15 Interestingly, though C neoformans often affects immunocompromised patients, the emerging pathogen of C gattii affects immunocompetent patients.7,17,23 Our patient’s undiagnosed diabetes may have been a risk factor for cryptococcal infection. His cryptococcal antigen titer was 1:256, with no evidence of other sites of involvement. We therefore believe this to be a rare case of direct inoculation secondary to an insect bite.