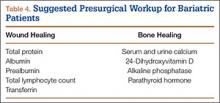

Serum levels of vitamin A, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin C should also be ordered, as many patients are deficient. Transferrin levels should be checked before surgery, as iron-deficiency anemia is common. Naghshineh and colleagues34 noted an anecdotal decrease in wound-healing complications in body-contouring surgery after correction of subclinical and clinical deficiencies in protein, arginine, glutamine, vitamin A, vitamin B12, vitamin C, folate, thiamine, iron, zinc, and selenium. Zinc deficiency was similarly implicated in wound-healing complications by Zorrilla and colleagues,35,36 who found a statistically significant delay in wound healing in patients with serum zinc levels under 95 mg/dL after total hip arthroplasty (THA)35 and hip hemiarthroplasty.36 To facilitate bone healing, physicians should give patients a thorough workup of levels of serum and urine calcium, 24-hydroxyvitamin D, and alkaline phosphatase. Osteomalacia typically presents with high alkaline phosphatase levels37 and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Therefore, physicians should monitor for these conditions. Although nonunion and aseptic loosening have not been reported as consequences of bariatric surgery, bone health should nevertheless be optimized when possible (Table 4).

Elective Orthopedic Surgery

Little is known about the true effect of weight-loss surgery on subsequent orthopedic procedures. Few investigators have explored the effect of surgery on arthrodesis, and the only recommendation for orthopedic surgeons is to be prepared for poor bone healing and the possibility of nonunion.38 Hidalgo and colleagues39 studied laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy performed a minimum of 6 months before another elective surgery. Two patients had lumbar laminectomies, 2 had lumbar discectomies, 1 had a cervical discectomy, and 1 had a rotator cuff repair. By most recent follow-up, there were no complications of any of the orthopedic procedures, and all patients had healed.

There is no recommended amount of time between bariatric surgery and elective orthopedic surgery. Maximum weight loss and stabilization are typically achieved 2 years after surgery.40 However, elective orthopedic surgery has been performed as early as 6 months after bariatric surgery. Inacio and colleagues41 studied 3 groups of patients who underwent total joint arthroplasty (TJA): those who had it less than 2 years after bariatric surgery, those who had it more than 2 years after bariatric surgery, and those who were obese but did not have bariatric surgery. Complications of TJA occurred within the first year in 2.9% of the patients who had it more than 2 years after bariatric surgery, in 5.9% of the patients who had it less than 2 years after bariatric surgery, and in 4.1% of the patients who did not undergo bariatric surgery. Similarly, Severson and colleagues2 evaluated intraoperative and postoperative complications of TKA in 3 groups of obese patients: those who had TKA before bariatric surgery, those who had TKA less than 2 years after bariatric surgery, and those who had TKA more than 2 years after bariatric surgery. Gastroplasty and bypass patients were included. BMI was statistically significantly higher in the preoperative group than in the other 2 groups, though mean BMI for all groups was above 35 kg/m2. Operative time and tourniquet time were reduced in patients who had TKA more than 2 years after bariatric surgery, but there was no significant difference in anesthesia time. There was also no difference in 90-day complication rates between patients who had TKA before bariatric surgery and those who had it afterward. Severson and colleagues2 recommended communicating the risks to all obese patients, whether they undergo weight-loss surgery or not.

Arthroplasty

Obese patients have a higher rate of complications after arthroplasty—hence the referrals to bariatric surgeons. Bariatric surgery and its associated weight loss might improve joint pain and delay the need for arthroplasty in some cases.42 Obese people are prone to joint degeneration from the excess weight, and from altered gait patterns (eg, exaggerated step width, slower walking speed, increased time in double-limb stance).43 Gait changes are reversible after weight loss.44 Hooper and colleagues45 found a 37% decrease in lower extremity complaints after surgical weight loss, even though mean BMI at final follow-up was still in the obese range.

Obesity itself is a risk factor for ligamentous instability, but it is unclear whether the risk is mitigated by bariatric surgery. Disruption of the anterior fibers of the medial collateral ligament is more common in obese patients, as are complications involving the extensor mechanism (eg, patellofemoral dislocation). As a result, slower postoperative rehabilitation is recommended.46 Although there is no recorded link between bariatric surgery and the development of ligamentous laxity, surgeons should be aware of the potential for medial collateral ligament avulsion in obese and formerly obese patients and have appropriate implants available.