Athletic Pubalgia

Athletic pubalgia, also known as sports hernia or core muscle injury, is an injury to the soft tissues of the lower abdominal or posterior inguinal wall. Although not fully understood, the condition is considered the result of repetitive trunk hyperextension and thigh hyperabduction resulting in shearing at the pubic symphysis where there is a muscle imbalance between the strong proximal thigh muscles and weaker abdominals. This condition is more common in men and typically is insidious in onset with a prolonged course recalcitrant to nonoperative treatment.18 In studies of chronic groin pain in athletes, the rate of athletic pubalgia as the primary etiology ranges from 39% to 85%.9,19,20

Patients typically complain of increasing pain in the lower abdominal and proximal adductors during activity. Symptoms include unilateral or bilateral lower abdominal pain, which can radiate toward the perineum, rectus muscle, and proximal adductors during sport but usually abates with rest.18 Athletes endorse they are not capable of playing at their full athletic potential. Symptoms are initiated with sudden forceful movements, as in sit-ups, sprints, and valsalva maneuvers like coughs and sneezes. Valsalva maneuvers worsen pain in about 10% of patients.21-23On physical examination with the patient supine, tenderness can be elicited over the pubic tubercle, abdominal obliques, and/or rectus abdominis insertion (Figure 3A). Athletes may also have tenderness at the adductor longus tendon origin at or near the pubic symphysis, which may make the diagnosis difficult to distinguish from an adductor strain.

Furthermore, resisted hip adduction, as described above, can elicit discomfort in 88% of patients.21 However, resisted sit-ups may help distinguish athletic pubalgia from other etiologies (Figure 3B). In this maneuver, the patient is supine with hips and knees flexed. The examiner stabilizes the contralateral pelvis and resists the patient’s attempted sit-up by pushing on the ipsilateral shoulder. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain at the inferolateral edge of the distal rectus abdominis.Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis is a painful overuse injury that results in noninfectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis from increased motion at this normally stable immobile joint.3 As with athletic pubalgia, the exact mechanism is unclear, but likely it is similar to the repetitive stress placed on the pubic symphysis by unequal forces of the abdominal and adductor muscles.24 The disease can result in bony erosions and cartilage breakdown with irregularity of the pubic symphysis.

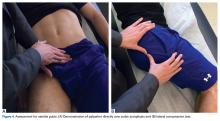

Athletes may complain of anterior and medial groin pain that can radiate to the lower abdominal muscles, perineum, inguinal region, and medial thigh. Walking, pelvic motion, adductor stretching, abdominal muscle exercises, and standing up can exacerbate pain.24 Some cases involve impaired internal or external rotation of the hip, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or adductor and abductor muscle weakness.25The distinguishing feature of osteitis pubis is pain over the pubic symphysis with direct palpation (Figure 4A). Examination maneuvers that place stress on the pubic symphysis can aid in diagnosis.26

For example, in the lateral compression test, the examiner places direct downward pressure on the greater trochanter with the patient in the lateral decubitus position (Figure 4B). The test is positive if the patient experiences discomfort at the pubic symphysis.26,27Intra-Articular Hip Pathology: Femoroacetabular Impingement

In athletes, FAI is a leading cause of intra-articular pathology, which can lead to labral tears.28,29 FAI lesions include cam-type impingement from an aspherical femoral head and pincer impingement from acetabular overcoverage, both of which limit internal rotation and cause acetabular rim abutment, which damages the labrum.

Athletes present with activity-related groin or hip pain that is exacerbated by hip flexion and internal rotation, with possible mechanical symptoms from labral tearing.30 However, the pain distribution varies. In a study by Clohisy and colleagues,31 of patients with symptomatic FAI that required surgical intervention, 88% had groin pain, 67% had lateral hip pain, 35% had anterior thigh pain, 29% had buttock pain, 27% had knee pain, and 23% had low back pain.

Careful attention should be given to range of motion in FAI patients, as they can usually flex their hip to 90° to 110°, and in this position there is limited internal rotation and asymmetric external rotation relative to the contralateral leg.32 The anterior impingement test is one of the most reliable tests for FAI (Figure 5A).32 With the patient supine, the hip is dynamically flexed to 90°, adducted, and internally rotated. A positive test elicits deep anterior groin pain that generally replicates the patient’s symptoms.29 The posterior impingement test is also performed with the patient supine; the unaffected hip is flexed and held by the patient while the affected limb is extended and externally rotated by the examiner (Figure 5B). Buttock pain can result when the femoral head contacts the posterior acetabular cartilage and rim.6,33 Mechanical symptoms, such as labral tears, can be assessed with the Stinchfield test and the McCarthy hip extension test. The Stinchfield test is performed by having the patient perform a straight leg raise to 45° and resist downward pressure. Pain indicates an intra-articular etiology, as the psoas muscle puts pressure on the anterolateral labrum.6 In the McCarthy hip extension test, the affected hip is taken from flexion into extension as the examiner rolls it in arcs of internal and external rotation. The test is positive if pain is reproduced when the hip is extended.34