Computed Tomography

The benefits of computed tomography (CT) outweigh the risk of radiation exposure. CT is most useful in characterizing osseous morphology.21 In FAI cases, CT can distinguish acetabular version abnormalities from femoral torsion (Figures 7A-7C), entities with very different treatment approaches.21

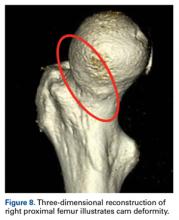

CT of the entire pelvis allows accurate objective measurement of acetabular version. Software advancements provide 3-dimensional reconstructions (Figure 8) and afford better appreciation of symptomatic pathomorphology by patients and more sophisticated measures by surgeons. Whereas CT reveals osseous structure, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates acuity and response of the osseous structures to the clinical condition (eg, bone marrow edema).Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is becoming essential in the work-up for nonarthritic hip pain.11,22 It is used for assessment of osseous, chondral, and musculotendinous soft tissues. Further, it affords appreciation of outside-the-hip-joint pathology that may mimic joint-centered pathology.

MRI techniques range from noncontrast to indirect and direct magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).22 Indirect MRA is performed with contrast medium administered through an intravenous line. Direct MRA has contrast administered intra-articularly and is more sensitive and specific for labral tears and ligamentous injury.23 Excellent detection of intra-articular pathology on noncontrast studies questions the need for MRA.24 Nevertheless, direct MRA can also be used as a therapeutic procedure when lidocaine is included in the injected gadolinium.

Labral tears, focal chondral defects, and stress or insufficiency fractures are important differentials in the work-up for nonarthritic hip pain. Over the dysplasia-to-FAI spectrum, MRI distinguishes symptomatic pathoanatomy from asymptomatic anatomical variants by revealing underlying bone edema. Capsule findings should also be considered.21The most practical classification of labral tears, proposed by Blankenbaker and colleagues,25 is based on tear type (frayed, unstable, flap), location, and extent. More than half of labral tears occur in the anterosuperior quadrant of the labrum.25

On noncontrast MRI, these tears appear as linear T2 hyperintensity within or through an otherwise homogeneously dark labrum. Accurate findings can be elusive because of variant labral anatomy (Figures 9A, 9B).26 Findings regarding the inside of the labrum can be signs of an overlying problem, such as FAI (Figures 10A-10C).Chondral damage is identified much as labral tears are. With chondral injury, the normal intermediate signal is interrupted by a fluid-intense signal extending to the subchondral bone. A fat-saturated T2or short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence is useful in emphasizing this finding.27

MRI detects osseous pathology from surrounding soft-tissue edema and bone remodeling to stress and fragility fractures. In athletes, the most common fractures are pubic rami, sacral, and apophyseal avulsion fractures.28 In all patients, attention should be given to the lower spine and the proximal femurs. Aside from MRI, nuclear medicine bone scan might also identify active osseous reaction representative of a fracture.

Conclusion

The work-up for nonarthritic hip pain substantiates differential diagnoses. A case’s complexity determines the course of diagnostic imaging. At presentation and at each step in the work-up, it is imperative to evaluate the entire clinical picture. The prudent clinician uses both clinical and radiographic findings to make the diagnosis and direct treatment.

Am J Orthop . 2017;46(1):17-22. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.