Pincer-type FAI may be caused by acetabular retroversion, coxa profunda, or protrusio acetabuli. Our understanding of what defines a pincer morphology has evolved significantly. Through efforts to better define structural features of the acetabular rim that represent abnormalities, we have improved our understanding of how these features may influence OA development. One example of improved understanding involves coxa profunda, classically defined as the medial acetabular fossa touching or projecting medial to the ilioischial line on an AP pelvis radiograph. Several studies have found that this classic definition poorly describes the “overcovered” hip, as it is present in 70% of females and commonly present (41%) in the setting of acetabular dysplasia.18,19 Acetabular retroversion was previously associated with hip OA. Although central acetabular retroversion is relatively uncommon, cranial acetabular retroversion is more common. Presence of a crossover sign on AP pelvis radiographs generally has been viewed as indicative of acetabular retroversion. However, alterations in pelvic tilt on supine or standing AP pelvis radiographs can result in apparent retroversion in the setting of normal acetabular anatomy20 and potentially influence the development of impingement.21 Zaltz and colleagues22 found that abnormal morphology of the anterior inferior iliac spine can also lead to the presence of a crossover sign in an otherwise anteverted acetabulum. Larson and colleagues23 recently found that a crossover sign is present in 11% of asymptomatic hips (19% of males) and may be considered a normal variant. A crossover sign can also be present in the setting of posterior acetabular deficiency with normal anterior acetabular coverage. Ultimately, acetabular retroversion might indicate pincer-type FAI or dysplasia or be a normal variant that does not require treatment. Global acetabular overcoverage, including coxa protrusio, may be associated with OA in population-based studies but is not uniformly demonstrated in all studies.16,24,25 A lateral center edge angle of >40° and a Tönnis angle (acetabular inclination) of <0° are commonly viewed as markers of global overcoverage.

FAI Treatment

Improvements in hip arthroscopy techniques and instrumentation have led to hip arthroscopy becoming the primary surgical technique for the treatment of most cases of FAI. Hip arthroscopy allows for precise visualization and treatment of labral and chondral disease in the central compartment by traction. Larson and colleagues26 reported complication rates for hip arthroscopy in a prospective series of >1600 cases. The overall complication rate was 8.3%, with higher rates noted in female patients and in the setting of traction time longer than 60 minutes. Nonetheless, major complications occurred in 1.1%, with only 0.1% having persistent disability. The most common complications were lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysesthesias (1.6%), pudendal nerve neuropraxia (1.4%), and iatrogenic labral/chondral damage (2.1%).

The importance of preserving the acetabular labrum is now well accepted from clinical and biomechanical evidence.27-29 As in previous studies in surgical hip dislocation,30 arthroscopic labral repair (vs débridement) results in improved clinical outcomes.31,32 Labral repair techniques currently focus on stable fixation of the labrum while maintaining the normal position of the labrum relative to the femoral head and avoiding labral eversion, which may compromise the hip suction seal. With continued technical advancements and biomechanical support, arthroscopic labral reconstruction is possible in the setting of labral deficiency, often resulting from prior resection. However, the optimal indications, surgical techniques, and long-term outcomes continue to be better defined. Open and arthroscopic techniques have shown similar ability to correct the typical mild to moderate cam morphology in FAI.33 Yet, inadequate femoral bony correction of FAI seems to be the most common cause for revision hip preservation surgery.9,10,17Mild to moderate acetabular rim deformities are commonly treated with hip arthroscopy. As our understanding of pincer-type FAI continues to improve, many surgeons are performing less- aggressive bone resection along the anterior rim. On the other hand, subspinous impingement was recently recognized as a form of extra-articular pincer FAI variant.34 Subspine decompression without true acetabular rim resection has become a more common treatment for pincer lesions and may be a consideration even with restricted range of motion after periacetabular osteotomy. Severe acetabular deformities with global overcoverage or acetabular protrusion are particularly challenging by arthroscopy, even for the most experienced surgeons. Although some improvement in deformity is feasible with arthroscopy, even cases reported in the literature have demonstrated incomplete deformity correction. Open surgical hip dislocation may continue to be the ideal treatment technique for severe pincer impingement.

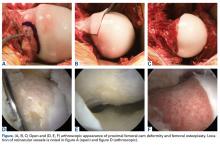

Cam-type FAI is commonly treated with hip arthroscopy (Figures A-F).

Dynamic examination during hip arthroscopy, similar to that performed with open techniques, can also be helpful in demonstrating FAI in the typical anterosuperior location. It may be crucial to perform an arthroscopic dynamic assessment in various positions (flexion-abduction, extension-abduction, flexion-internal rotation) in order to more accurately evaluate potential regions of impingement. Fluoroscopic imaging is generally used to guide and confirm appropriate deformity correction.35 Anterior and anterolateral head–neck junction deformity is well accessed in 30° to 45° of hip flexion. Both interportal and T-type capsulotomies can be used, generally depending on surgeon preference. FAI deformity extending distal along the head–neck junction can be more challenging to access without a T-type capsulotomy. FAI deformities that extend laterally and are visible on an AP pelvis radiograph remain the most challenging aspect of arthroscopic FAI surgery. These areas of deformity can be better accessed with the hip in extension and sometimes even with traction applied. Access to the more cranial and posterior extensions of these deformities is more difficult in the setting of femoral retroversion or relative femoral retroversion, which can often coexist. Fabricant and colleagues36 found relative femoral retroversion (<5° anteversion) was associated with poorer outcomes after arthroscopic treatment of FAI.Open surgical techniques will continue to have an important role in the treatment of severe and complex FAI deformities in which arthroscopic techniques do not consistently achieve adequate bony correction (Figures A-F). Surgical hip dislocation remains a powerful surgical technique for deformity correction in FAI. Sink and colleagues37 reported rates of complications after open surgical hip dislocation in the ANCHOR study group. In a cohort of 334 hips (302 patients), trochanteric nonunion occurred in 1.8% of cases, and there were no cases of avascular necrosis. Overall major complications were observed in 4.8% of cases, with 0.3% having chronic disability. Excellent outcomes, including high rates of return to sports, have been reported after surgical hip dislocation for FAI.38 Midterm studies from the early phase of surgical treatment of FAI have helped identify factors that may play a major role in optimizing patient outcomes.