Of the 30 surgeons, 1 (3%) came within 10 mm of the ultrasound for ASIS, 1 (3%) for GT, 4 (13%) for RO, 5 (17%) for SIR, and 1 (3%) for PT (Table 1).

TAL as determined by CI was 16 mm medial and 29 mm inferior for ASIS; 8 mm anterior and 22 mm superior for GT; 10 mm medial and 25 mm inferior for RO; 5 mm lateral and 5 mm inferior for SIR; and 28 mm medial and 16 mm inferior for PT (Figure 3, Table 2). Interobserver variability determined by prediction interval had a range of 18 mm medial to lateral × 36 mm proximal to distal for ASIS; 33 mm anterior to posterior × 48 mm superior to inferior for GT; 41 mm medial to distal × 54 mm proximal to distal for RO; 51 mm medial to lateral × 74 mm proximal to distal for SIR; and 49 mm medial to distal × 61 mm proximal to distal for PT.

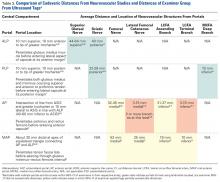

Given the difference between examiner data (direction and distance from ultrasound labels) and published data (distance to significant neurovascular structures), inaccurate identification of surface landmarks has the potential to lead to AP and MAP damage (Table 3). The examiner GT and ASIS surface landmarks used for AP overlapped directly with the safe distances for the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the terminal branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Discussion

Others have investigated examiners’ use of palpation, compared with ultrasound, to identify common shoulder and knee structures.8-10 In a 2011 systematic review, Gilliland and colleagues11 confirmed that accuracy was improved with use of ultrasound (vs palpation) for injections in the shoulder, hip, knee, wrist, and ankle. Given the scarcity of data in this setting, we conducted the present study to assess the precision and accuracy of expert arthroscopists in identifying common surface landmarks. We hypothesized that physical examination and ultrasound examination would differ significantly in precisely and accurately identifying these landmarks.

Working with a standard awake volunteer, our test group of examiners was consistently inaccurate when they accepted ultrasonographer-placed labels as the ideal. Precision within the group, however, trended toward close agreement; examiners consistently placed labels in the same direction and approximate magnitude away from ultrasonographer labels. This suggests that a discrepancy between the ultrasonographic surface structure definitions taught to ultrasonographers and the manually identified definitions taught to surgeons for arthroscopy (training bias) can generate differences in landmark identification.

Given reported low rates of complications in the creation of standard surface anatomy portals, more data is needed to correlate whether safe distance guidelines best apply to the points identified by hip experts or the points identified by ultrasonographers. In a 2013 systematic review, Harris and colleagues8 found a 7.5% overall complication rate, with temporary neuropraxia 1 of the 2 most common complications. Whether adding ultrasound to physical examination for the creation of some or all portals will reduce the incidence of these problems is unknown. Regardless of the anatomical area referenced by experts for portal creation, the tight grouping of examiner marks in our study supports a consensus regarding the location of the landmarks studied.

In our study of the use of surface anatomical landmarks for the creation of portals, we analyzed 4 previously described locations: ALP, AP, PLP, and MAP. ALP, AP, and PLP directly reference at least 1 surface anatomical structure; AP references 2 anatomical structures (ASIS, GT); and MAP indirectly references ASIS and GT and directly references ALP and AP. In cadaveric and radiographic studies, 7 neurovascular structures have been described in proximity to ALP, AP, MAP, and PLP: superior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, lateral circumflex femoral artery, and medial circumflex femoral artery.5,6 Our results showed that use of surface anatomy in AP and MAP creation most likely places structures at risk, given the overlap of examiner CIs and the previously published cadaveric5,6 and radiographic7 data.

Hua and colleagues12 confirmed the feasibility of using ultrasound for the creation of hip arthroscopy portals. More data is needed to assess how the standard palpation-and-fluoroscopy method described by Byrd3 compares with an ultrasound-guided technique in safety and cost. However, data from our study should not be used to justify a demand for ultrasound during arthroscopy portal establishment, as limitations do not permit such a recommendation.

With diagnostic injection remaining a mainstay of differential diagnosis and treatment about the hip,1 the data presented here suggest a potential for ultrasound in enhancing outcomes. There is evidence supporting the role of image guidance in improving palpation accuracy in the area of the biceps tendon in the forearm.10 Potentially, identification and treatment of specific extra-articular structures surrounding the hip could be made safer with more routine use of ultrasound.