User login

Lumateperone for major depressive episodes in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder

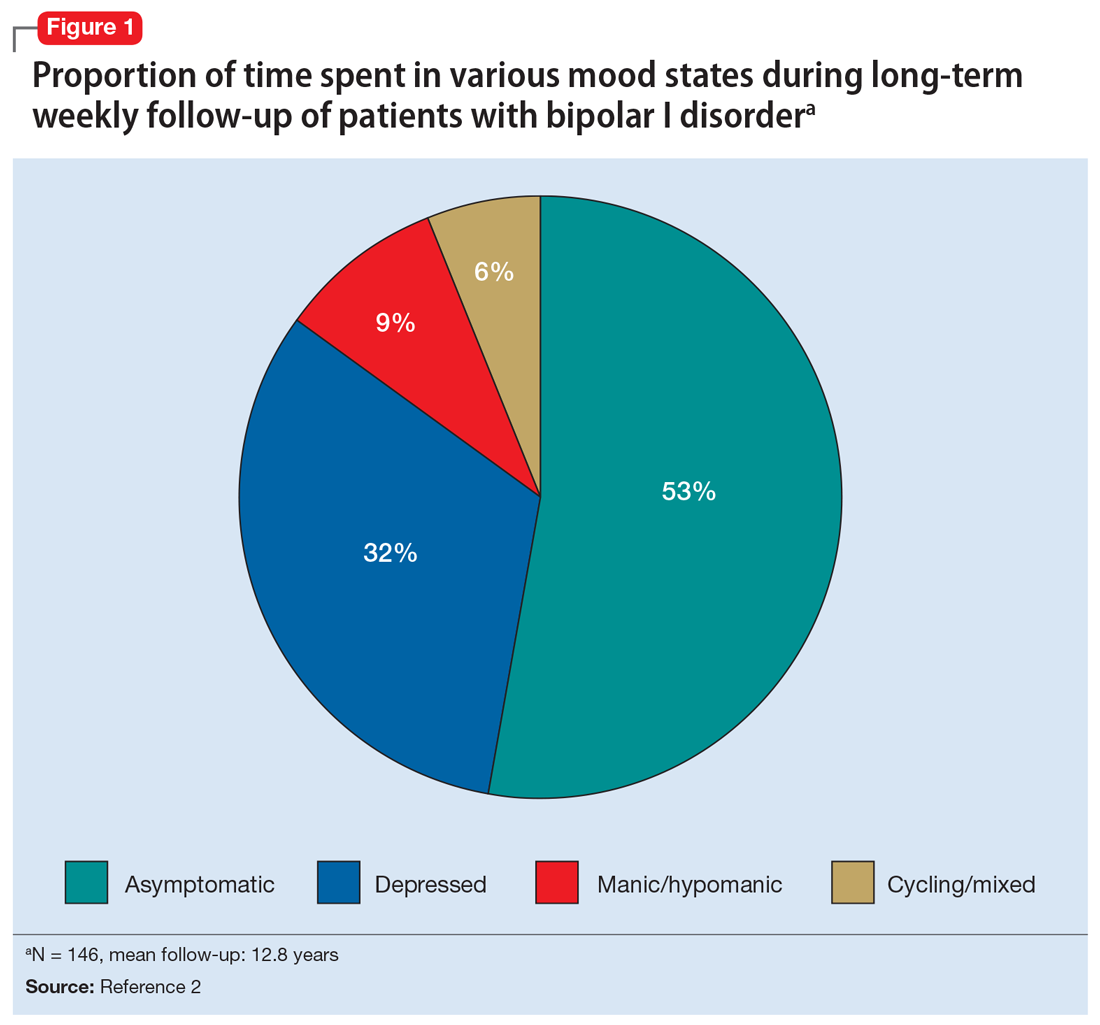

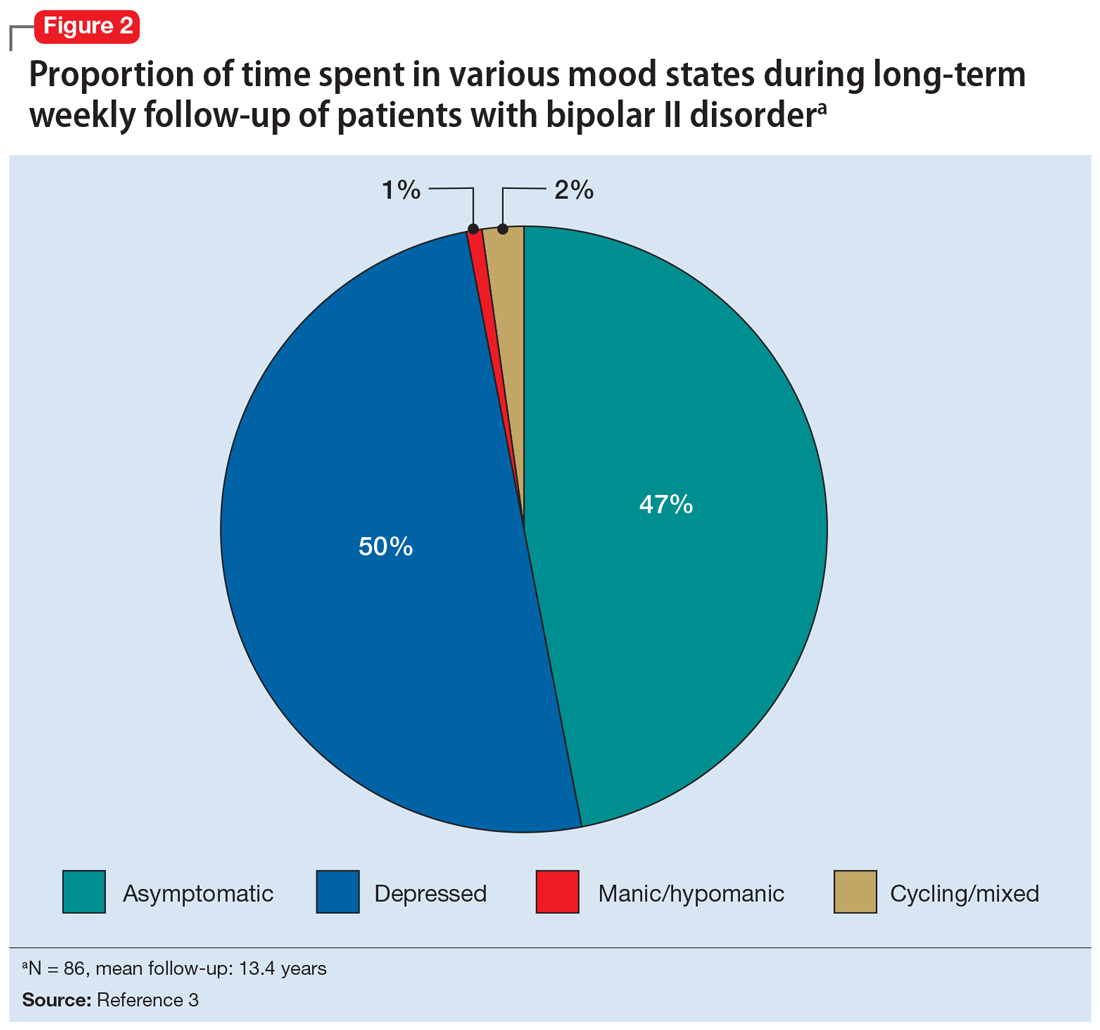

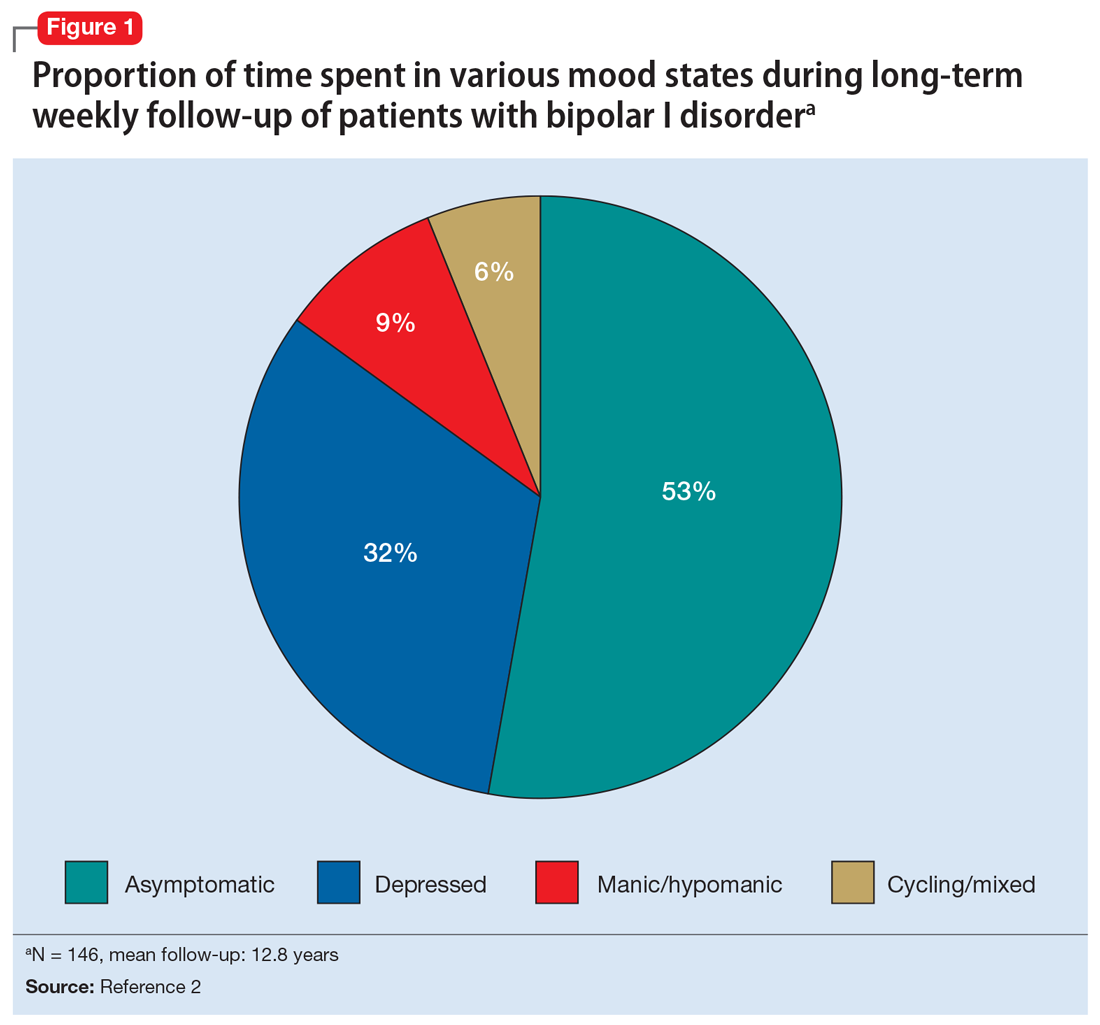

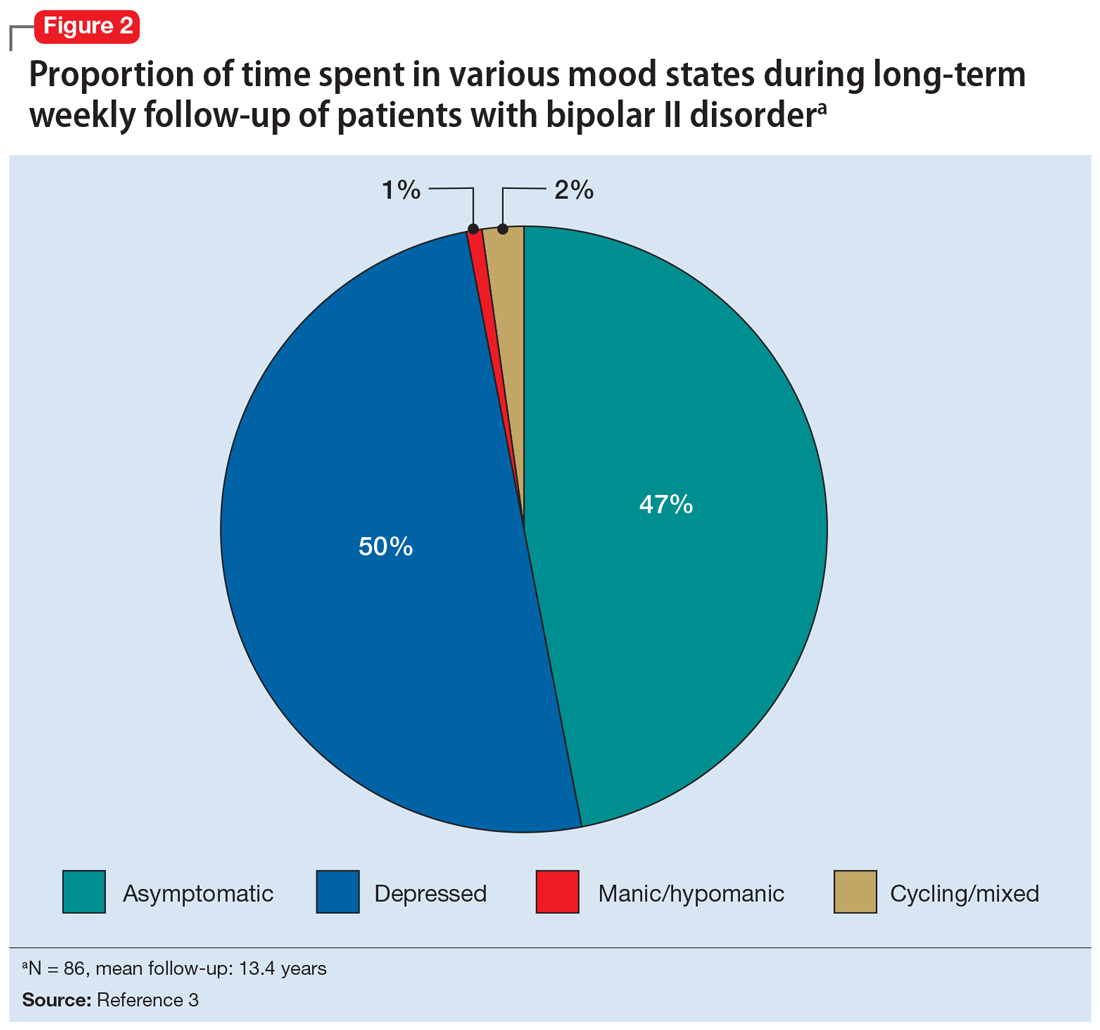

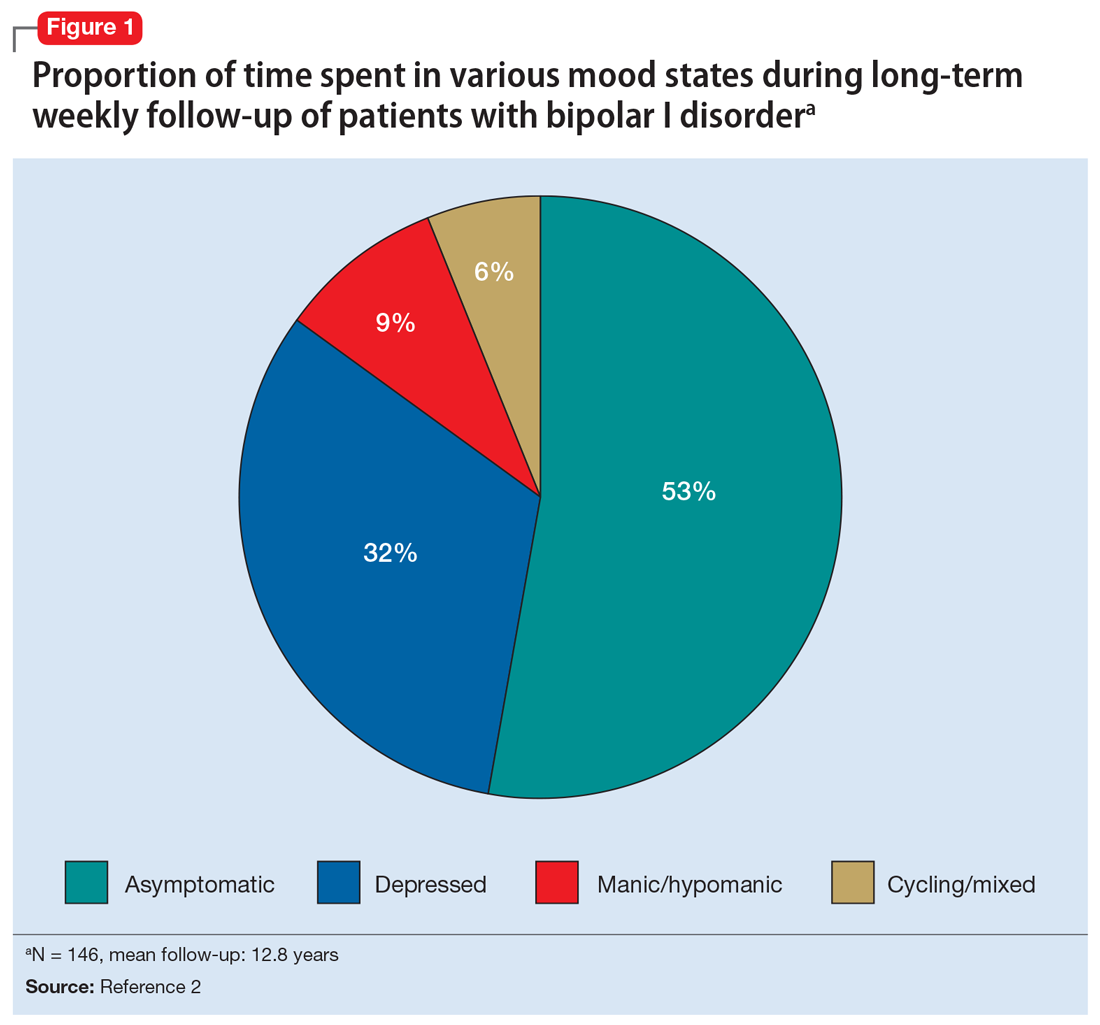

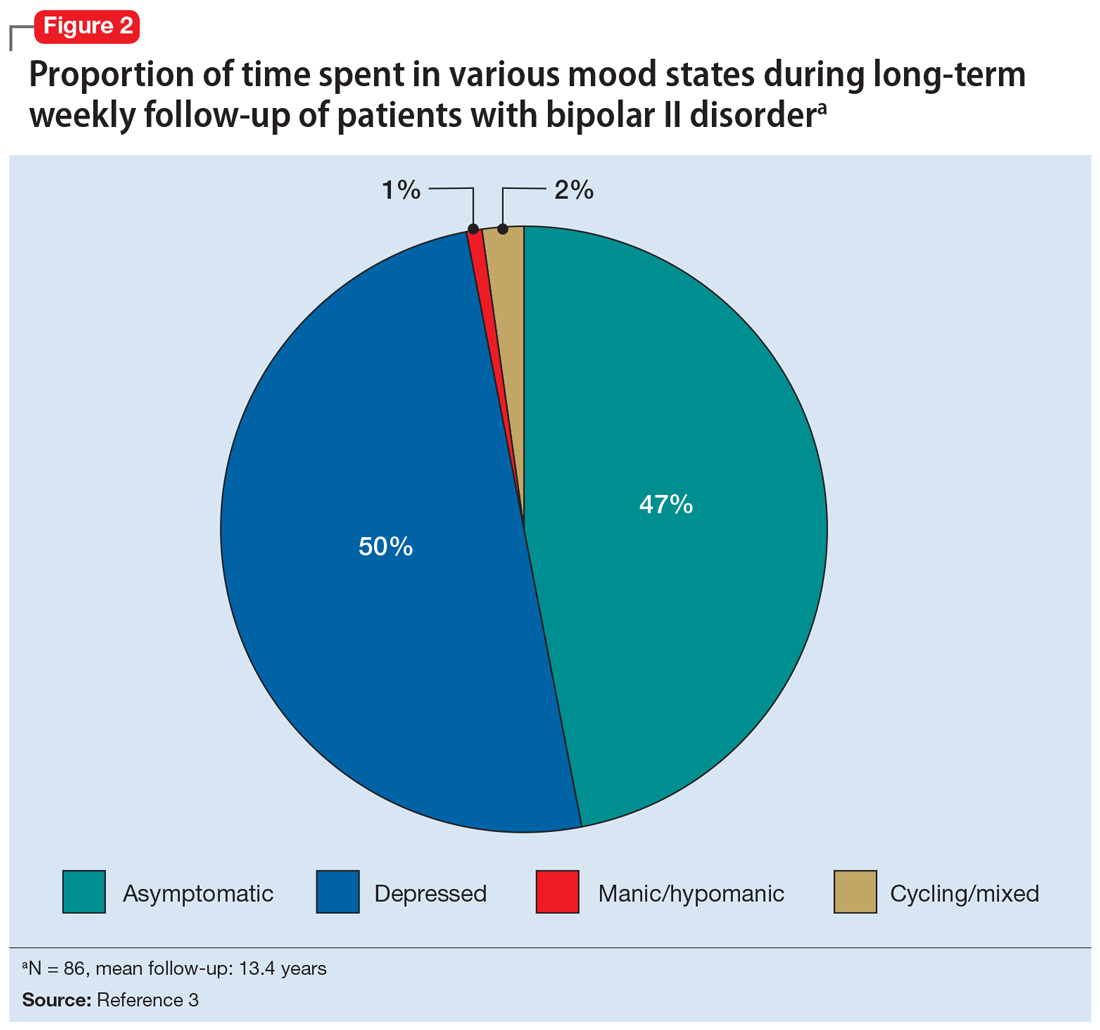

Among patients with bipolar I or II disorder (BD I or II), major depressive episodes represent the predominant mood state when not euthymic, and are disproportionately associated with the functional disability of BD and its suicide risk.1 Long-term naturalistic studies of weekly mood states in patients with BD I or II found that the proportion of time spent depressed greatly exceeded that spent in a mixed, hypomanic, or manic state during >12 years of follow-up (Figure 12and Figure 23). In the 20th century, traditional antidepressants represented the sole option for management of bipolar depression despite concerns of manic switching or lack of efficacy.4,5 Efficacy concerns were subsequently confirmed by placebo-controlled studies, such as the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial, which found limited effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressants for bipolar depression.6 Comprehensive reviews of randomized controlled trials and observational studies documented the risk of mood cycling and manic switching, especially in patients with BD I, even if antidepressants were used in the presence of mood-stabilizing medications.7,8

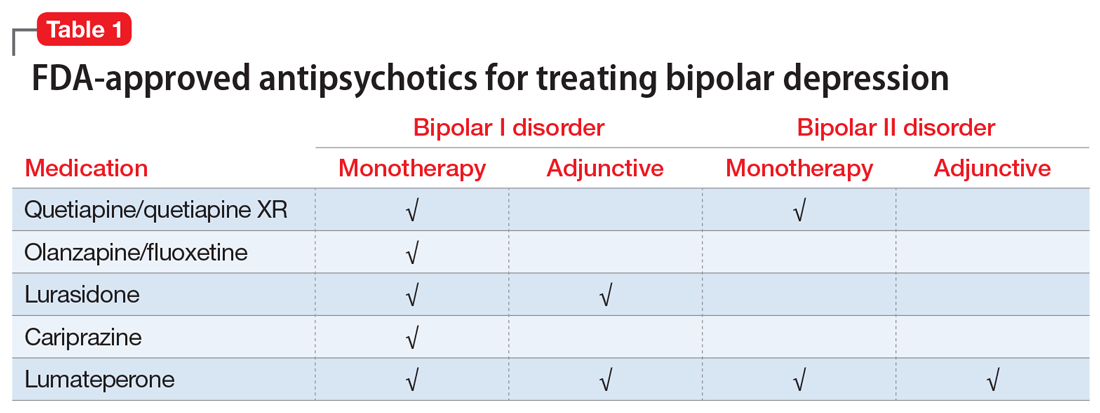

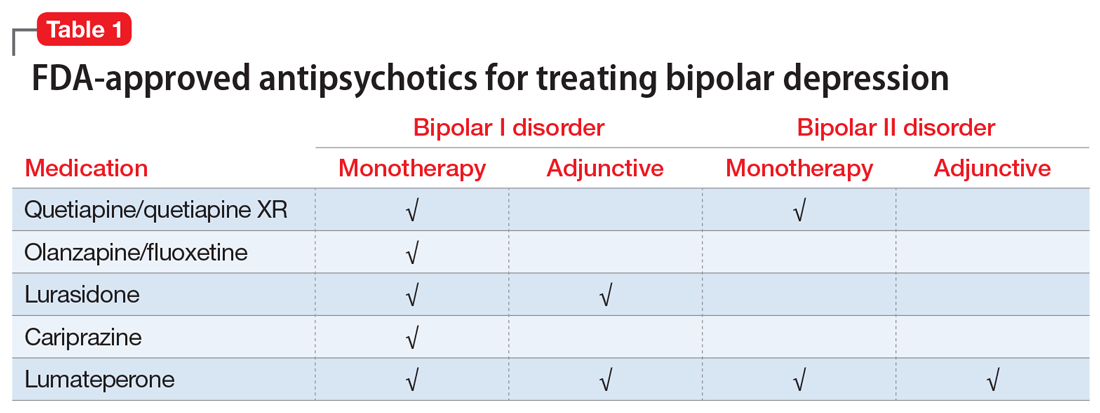

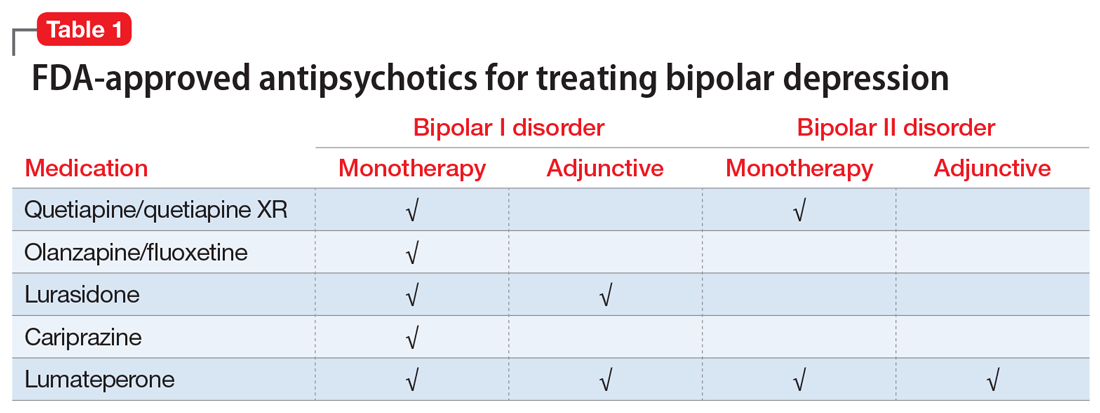

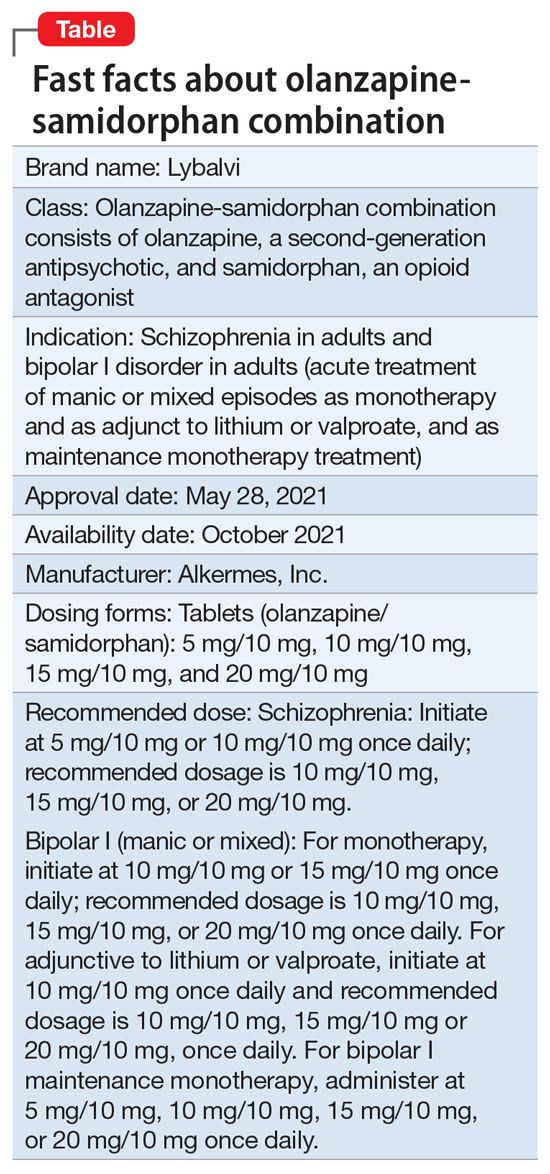

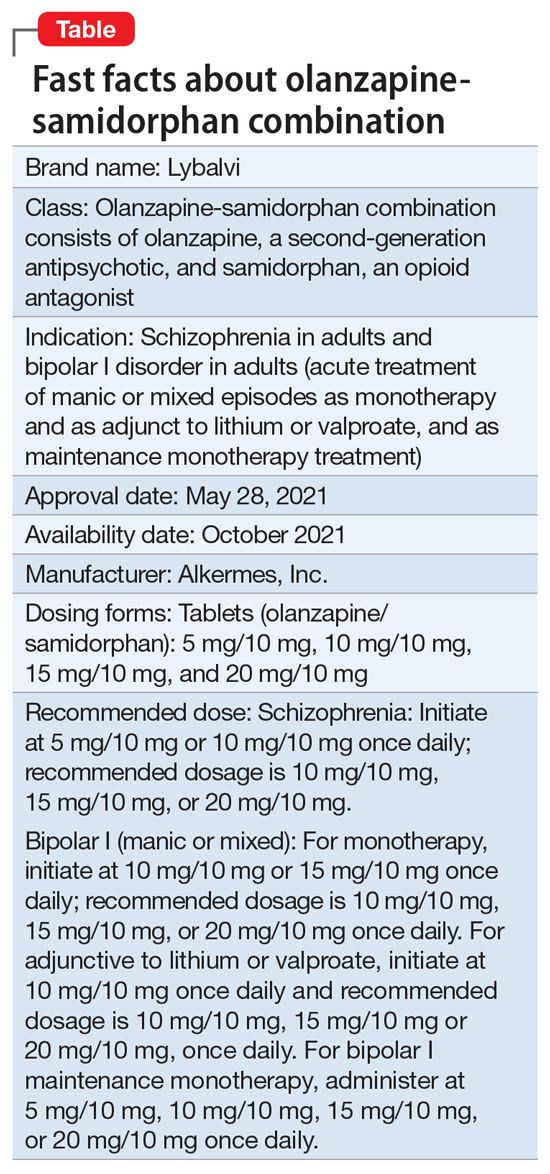

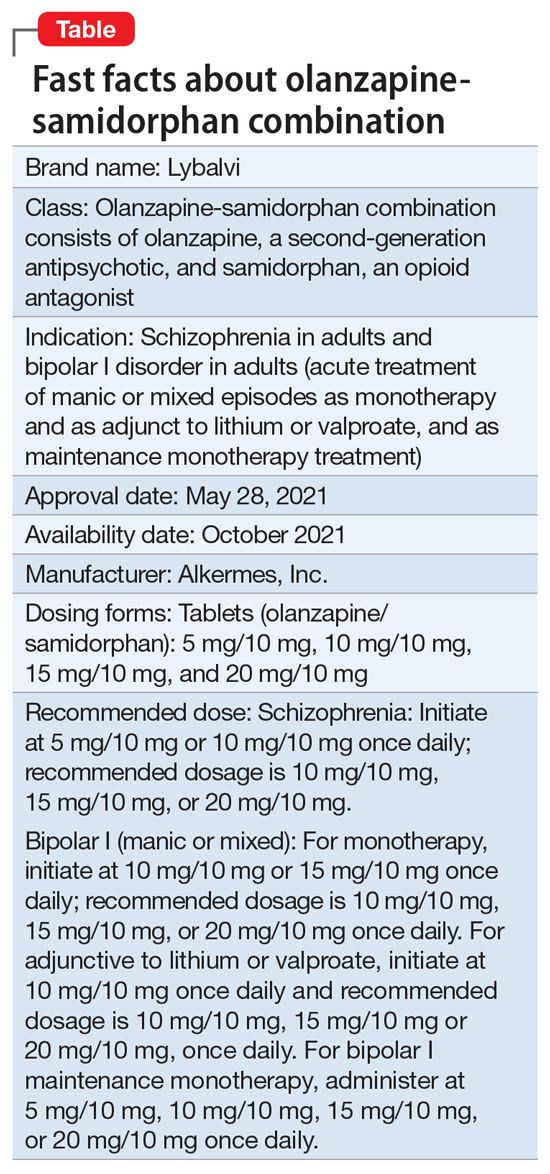

Several newer antipsychotics have been FDA-approved for treating depressive episodes associated with BD (Table 1). Approval of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) in December 2003 for depressive episodes associated with BD I established that mechanisms exist which can effectively treat acute depressive episodes in patients with BD without an inordinate risk of mood instability. Subsequent approval of quetiapine in October 2006 for depression associated with BD I or II, lurasidone in June 2013, and cariprazine in May 2019 for major depression in BD I greatly expanded the options for management of acute bipolar depression. However, despite the array of molecules available, for certain patients these agents presented tolerability issues such as sedation, weight gain, akathisia, or parkinsonism that could hamper effective treatment.9 Safety and efficacy data in bipolar depression for adjunctive use with lithium or divalproex/valproate (VPA) also are lacking for quetiapine, OFC, and cariprazine.10,11 Moreover, despite the fact that BD II is as prevalent as BD I, and that patients with BD II have comparable rates of comorbidity, chronicity, disability, and suicidality,12 only quetiapine was approved for acute treatment of depression in patients with BD II. This omission is particularly problematic because the depressive episodes of BD II predominate over the time spent in hypomanic and cycling/mixed states (50.3% for depression vs 3.6% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined), much more than is seen with BD I (31.9% for depression vs 14.8% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined).2,3 The paucity of data for the use of newer antipsychotics in BD II depression presents a problem when patients cannot tolerate or refuse to consider quetiapine. This prevents clinicians from engaging in evidence-based efficacy discussions of other options, even if it is assumed that the tolerability profile for BD II depression patients may be similar to that seen when these agents are used for BD I depression.

Continue to: Table 1...

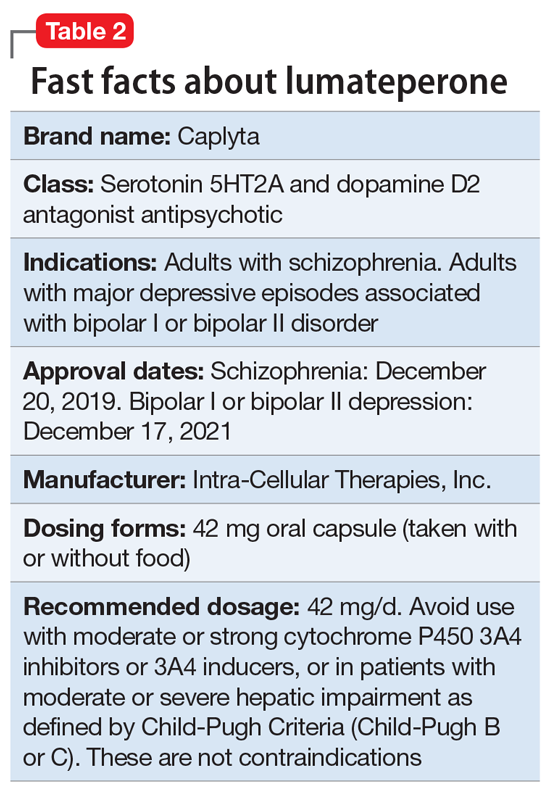

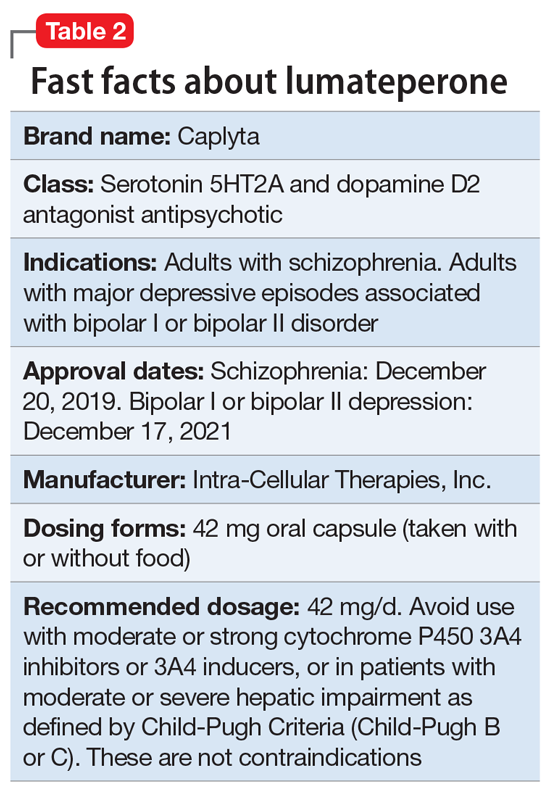

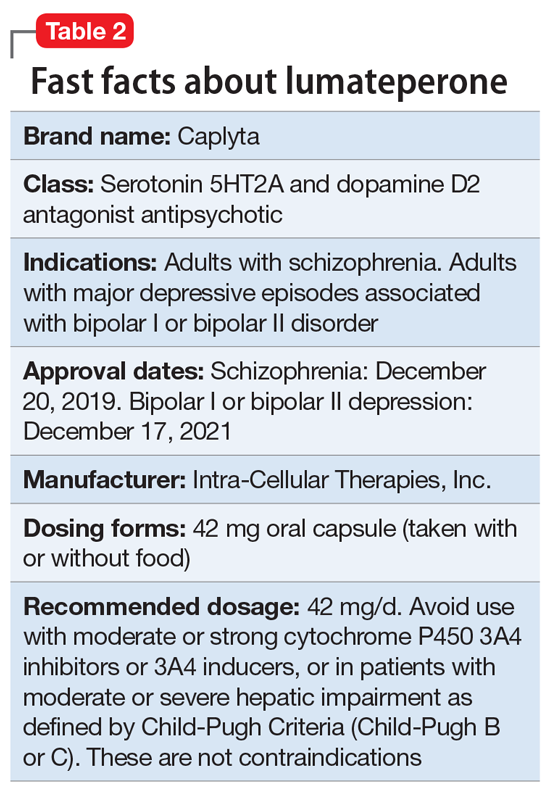

Lumateperone (Caplyta) is a novel oral antipsychotic initially approved in 2019 for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia. It was approved in December 2021 for the management of depression associated with BD I or II in adults as monotherapy or when used adjunctively with the mood stabilizers lithium or VPA (Table 2).13 Lumateperone possesses certain binding affinities not unlike those in other newer antipsychotics, including high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), low affinity for dopamine D2 receptors (Ki 32 nM), and low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).13,14 However, there are some distinguishing features: the ratio of 5HT2A receptor affinity to D2 affinity is 60, greater than that for other second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) such as risperidone (12), olanzapine (12.4) or aripiprazole (0.18).15 At steady state, D2 receptor occupancy remains <40%, and the corresponding rates of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)/akathisia differed by only 0.4% for lumateperone vs placebo in short-term adult clinical schizophrenia trials,13,16 by 0.2% for lumateperone vs placebo in the monotherapy BD depression study, and by 1.7% in the adjunctive BD depression study.13,17,18 Lumateperone also exhibited no clinically significant impact on metabolic measures or serum prolactin during the 4-week schizophrenia trials, with mean weight gain ≤1 kg for the 42 mg dose across all studies.19 This favorable tolerability profile for endocrine and metabolic adverse effects was also seen in the BD depression studies. Across the 2 BD depression monotherapy trials and the single adjunctive study, the only adverse reactions occurring in ≥5% of lumateperone-treated patients and more than twice the rate of placebo were somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth.13 There was also no single adverse reaction leading to discontinuation in the BD depression studies that occurred at a rate >2% in patients treated with lumateperone.13

In addition to the low risk of adverse events of all types, lumateperone has several pharmacologic features that distinguish it from other agents in its class. One unique aspect of lumateperone’s pharmacology is differential actions at presynaptic and postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors noted in preclinical assays, a property that may explain its ability to act as an antipsychotic despite low D2 receptor occupancy.16 Preclinical assays also predicted that lumateperone was likely to have antidepressant effects.15,19,20 Unlike every SGA except ziprasidone, lumateperone also possesses moderate binding affinity for serotonin transporters (SERT) (Ki 33 nM), with SERT occupancy of approximately 30% at 42 mg.21 Lumateperone facilitates dopamine D1-mediated neurotransmission, and this is associated with increased glutamate signaling in the prefrontal cortex and antidepressant actions.14,22 While the extent of SERT occupancy is significantly below the ≥80% SERT occupancy seen with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, it is hypothesized that near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor might act synergistically with modest 5HT reuptake inhibition and D1-mediated effects to promote the downstream glutamatergic effects that correlate with antidepressant activity (eg, changes in markers such as phosphorylation of glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits, potentiation of AMPA receptor-mediated transmission).15,22

Continue to: Clinical implications...

Clinical implications

The approval of lumateperone for both BD I and BD II depression, and for its use as monotherapy and for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA, satisfies several unmet needs for the management of acute major depressive episodes in patients with BD. Clinicians now have both safety and tolerability data to present to their bipolar spectrum patients regardless of subtype, and regardless of whether the patient requires mood stabilizer therapy. The tolerability advantages for lumateperone seen in schizophrenia trials were replicated in a diagnostic group that is very sensitive to D2-related adverse effects, and for whom any signal of clinically significant weight gain or sedation often represents an insuperable barrier to patient acceptance.23

Efficacy in adults with BD I or II depression.

The efficacy of lumateperone for major depressive episodes has been established in 2 pivotal, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in BD I or II patients: 1 monotherapy study,17 and 1 study when used adjunctively to lithium or VPA.18 The first study was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled monotherapy trial (study 404) in which 377 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode were randomized in a 1:1 manner to lumateperone 42 mg/d or placebo given once daily in the evening. Symptom entry criteria included a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall BD illness subscales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale–Bipolar Version Severity scale (CGI-BP-S) at screening and at baseline.17 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) at screening and at baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS. Several secondary efficacy measures were examined, including the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS), or remission (MADRS score ≤12), and differential changes in MADRS scores from baseline for BD I and BD II subgroups.17

The patient population was 58% female and 91% White, with 79.9% diagnosed as BD I and 20.1% as BD II. The least squares mean changes on the MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 were lumateperone 42 mg/d: -16.7 points; placebo: -12.1 points (P < .0001), and the effect size for this difference was moderate: 0.56. Secondary analyses indicated that 51.1% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 36.7% taking placebo met response criteria (P < .001), while 39.9% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 33.5% taking placebo met remission criteria (P = .018). Importantly, depression improvement was observed both in patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and in those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001).

The second pivotal trial (study 402) was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjunctive trial in which 528 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode despite treatment with lithium or VPA were randomized in a 1:1:1 manner to lumateperone 28 mg/d, lumateperone 42 mg/d, or placebo given once daily in the evening.18 Like the monotherapy trial, symptom entry criteria included a MADRS total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall illness CGI-BP-S subscales at screening and baseline.18 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the YMRS at screening and baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS for lumateperone 42 mg/d compared to placebo. Secondary efficacy measures included MADRS changes for lumateperone 28 mg/d and the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS) or remission (MADRS score ≤12).

The patient population was 58% female and 88% White, with 83.3% diagnosed as BD I, 16.7% diagnosed as BD II, and 28.6% treated with lithium vs 71.4% on VPA. The effect size for the difference in MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 for lumateperone 42 mg/d was 0.27 (P < .05), while that for the lumateperone 28 mg/d dose did not reach statistical significance. Secondary analyses indicated that response rates for lumateperone 28 mg/d and lumateperone 42 mg/d were significantly higher than for placebo (both P < .05). Response rates were placebo: 39%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 50%; and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 45%. Remission rates were similar at Day 43 in both lumateperone groups compared with placebo: placebo: 31%, lumateperone 28 mg/d: 31%, and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 28%.18 As of this writing, a secondary analysis by BD subtype has not yet been presented.

A third study examining lumateperone monotherapy failed to establish superiority of lumateperone over placebo (NCT02600494). The data regarding tolerability from that study were incorporated in product labeling describing adverse reactions.

Continue on to: Adverse reactions...

Adverse reactions

In the positive monotherapy trial, there were 376 patients in the modified intent-to-treat efficacy population to receive lumateperone (N = 188) or placebo (N = 188) with nearly identical completion rates in the active treatment and placebo cohorts: lumateperone, 88.8%; placebo, 88.3%.17 The proportion experiencing mania was low in both cohorts (lumateperone, 1.1%; placebo, 2.1%), and there was 1 case of hypomania in each group. One participant in the lumateperone group and 1 in the placebo group discontinued the study due to a serious adverse event of mania. There was no worsening of mania in either group as measured by mean change in the YMRS score. There was also no suicidal behavior in either cohort during the study. Pooling the 2 monotherapy trials, the adverse events that occurred at ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 13%, placebo: 3%), dizziness (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 4%), and nausea (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 3%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 1.3%, placebo: 1.1%.13 Mean weight change at Day 43 was +0.11 kg for lumateperone and +0.03 kg for placebo in the positive monotherapy trial.17 Moreover, compared to placebo, lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant. No patient exhibited a corrected QT interval >500 ms at any time, and increases ≥60 ms from baseline were similar between the lumateperone (n = 1, 0.6%) and placebo (n = 3, 1.8%) cohorts.

Complete safety and tolerability data for the adjunctive trial has not yet been published, but discontinuation rates due to treatment-emergent adverse effects for the 3 arms were: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 5.6%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 1.7%; and placebo: 1.7%. Overall, 81.4% of patients completed the trial, with only 1 serious adverse event (lithium toxicity) occurring in a patient taking lumateperone 42 mg/d. While this led to study discontinuation, it was not considered related to lumateperone exposure by the investigator. There was no worsening of mania in either lumateperone dosage group or the placebo cohort as measured by mean change in YMRS score: -1.2 for placebo, -1.4 for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and -1.6 for lumateperone 42 mg/d. Suicidal behavior was not observed in any group during treatment. The adverse events that occurred at rates ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone, 13%; placebo, 3%), dizziness (lumateperone, 11%; placebo, 2%), and nausea (lumateperone, 9%; placebo, 4%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone, 4.0%, placebo, 2.3%.13 Mean weight changes at Day 43 were +0.23 kg for placebo, +0.02 kg for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and 0.00 kg for lumateperone 42 mg/d.18 Compared to placebo, both doses of lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant.18

Lastly, the package insert notes that in an uncontrolled, open-label trial of lumateperone for up to 6 months in patients with BD depression, the mean weight change was -0.01 ± 3.1 kg at Day 175.13

Continue on to: Pharmacologic profile...

Pharmacologic profile

Lumateperone’s preclinical discovery program found an impact on markers associated with increased glutamatergic neurotransmission, properties that were predicted to yield antidepressant benefit.14,15,24 This is hypothesized to be based on the complex pharmacology of lumateperone, including dopamine D1 agonism, modest SERT occupancy, and near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor.15,22 Dopamine D2 affinity is modest (32 nM), and the D2 receptor occupancy at the 42 mg dose is low. These properties translate to rates of EPS in clinical studies of schizophrenia and BD that are close to that of placebo. Lumateperone has very high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), which also helps mitigate D2-related adverse effects and may be part of the therapeutic antidepressant mechanism. Underlying the tolerability profile is the low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).

Clinical considerations

Data from the lumateperone BD depression trials led to it being only the second agent approved for acute major depression in BD II patients, and the only agent which has approvals as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy for both BD subtypes. The monotherapy trial results substantiate that lumateperone was robustly effective regardless of BD subtype, with significant improvement in depressive symptoms experienced by patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001). Effect sizes in acute BD depression studies are much larger in monotherapy trials than in adjunctive trials, as the latter group represents patients who have already failed pretreatment with a mood stabilizer.25,26 In the lurasidone BD I depression trials, the effect size based on mean change in MADRS score over the course of 6 weeks was 0.51 in the monotherapy study compared to 0.34 when used adjunctively with lithium or VPA.25,26 In the lumateperone adjunctive study, the effect size for the difference in mean MADRS total score from baseline for lumateperone 42 mg/d, was 0.27 (P < .05). Subgroup analyses by BD subtype are not yet available for adjunctive use, but the data presented to FDA were sufficient to permit an indication for adjunctive use across both diagnostic groups.

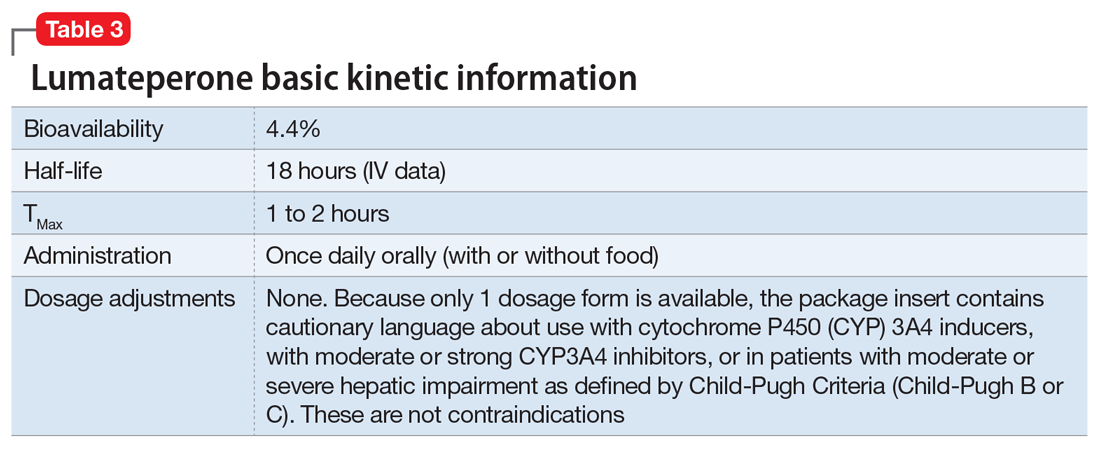

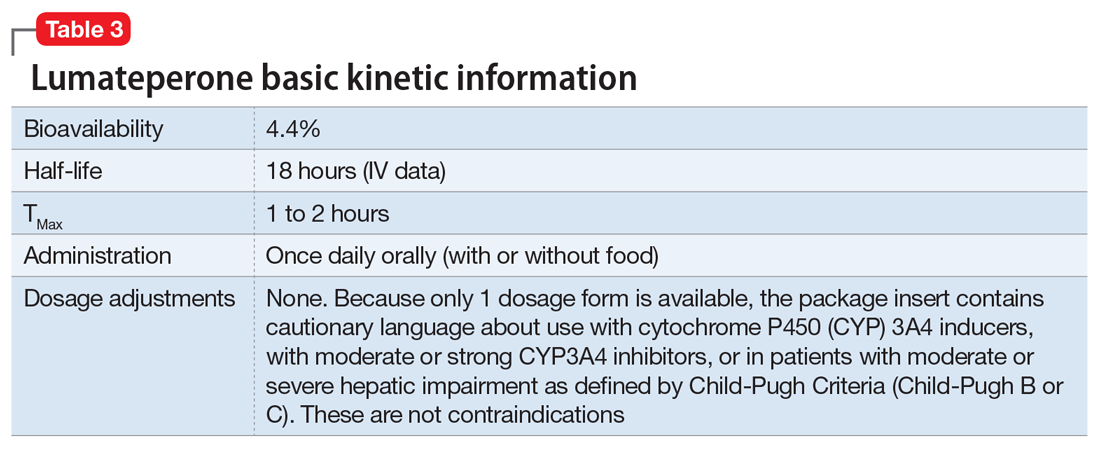

The absence of clinically significant EPS, the minimal impact on metabolic or endocrine parameters, and the lack of a need for titration are all appealing properties. At the present there is only 1 marketed dose (42 mg capsules), so the package insert includes cautionary language regarding situations when a patient might encounter less drug exposure (concurrent use of cytochrome P450 [CYP] 3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure due to concurrent use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, as well as in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria (Child-Pugh B or C). These are not contraindications.

Unique properties of lumateperone include efficacy established as monotherapy for BD I and BD II patients, and efficacy for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA. Additionally, the extremely low rates of significant EPS and lack of clinically significant metabolic or endocrine adverse effects are unique properties of lumateperone.13

Why Rx? Reasons to prescribe lumateperone for adult BD depression patients include:

- data support efficacy for BD I and BD II patients, and for monotherapy or adjunctive use with lithium/VPA

- favorable tolerability profile, including no significant signal for EPS, endocrine or metabolic adverse effects, or QT prolongation

- no need for titration.

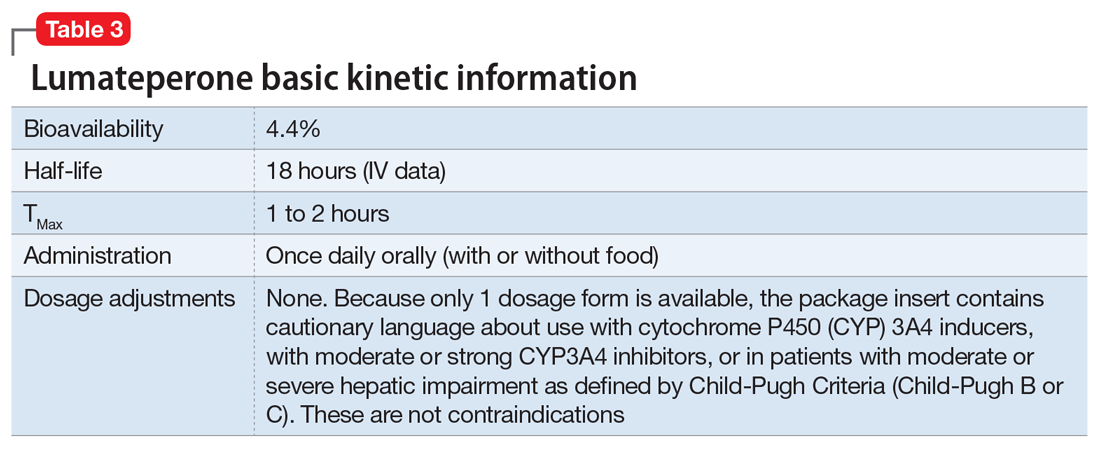

Dosing. There is only 1 dose available for lumateperone: 42 mg capsules (Table 3). As the dose cannot be modified, the package insert contains cautionary language regarding situations with less drug exposure (use of CYP3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure (use with moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria [Child-Pugh B or C]). These are not contraindications. Based on newer pharmacokinetic studies, lumateperone does not need to be dosed with food, and there is no clinically significant interaction with UGT1A4 inhibitors such as VPA.

Contraindications. The only contraindication is known hypersensitivity to lumateperone.

Bottom Line

Data support the efficacy of lumateperone for treating depressive episodes in adults with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, either as monotherapy or adjunctive to lithium or divalproex/valproate. Potential advantages of lumateperone for this indication include a favorable tolerability profile and no need for titration.

1. Malhi GS, Bell E, Boyce P, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(8):805-821.

2. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

3. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

4. Post RM. Treatment of bipolar depression: evolving recommendations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):11-33.

5. Pacchiarotti I, Verdolini N. Antidepressants in bipolar II depression: yes and no. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2021;47:48-50.

6. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711-1722.

7. Allain N, Leven C, Falissard B, et al. Manic switches induced by antidepressants: an umbrella review comparing randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):106-116.

8. Gitlin MJ. Antidepressants in bipolar depression: an enduring controversy. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):25.

9. Verdolini N, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Del Matto L, et al. Long-term treatment of bipolar disorder type I: a systematic and critical review of clinical guidelines with derived practice algorithms. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(4):324-340.

10. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017), part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):180-195.

11. Vraylar [package insert]. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2019.

12. Chakrabarty T, Hadijpavlou G, Bond DJ, et al. Bipolar II disorder in context: a review of its epidemiology, disability and economic burden. In: Parker G. Bipolar II Disorder: Modelling, Measuring and Managing. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2019:49-59.

13. Caplyta [package insert]. New York, NY: Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc.; 2021.

14. Davis RE, Correll CU. ITI-007 in the treatment of schizophrenia: from novel pharmacology to clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(6):601-614.

15. Snyder GL, Vanover KE, Zhu H, et al. Functional profile of a novel modulator of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate neurotransmission. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232:605-621.

16. Vanover KE, Davis RE, Zhou Y, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy of lumateperone (ITI-007): a positron emission tomography study in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):598-605.

17. Calabrese JR, Durgam S, Satlin A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lumateperone for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2021;178(12):1098-1106.

18. Yatham LN, et al. Adjunctive lumateperone (ITI-007) in the treatment of bipolar depression: results from a randomized clinical trial. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting. May 1-3, 2021; virtual conference.

19. Vanover K, Glass S, Kozauer S, et al. 30 Lumateperone (ITI-007) for the treatment of schizophrenia: overview of placebo-controlled clinical trials and an open-label safety switching study. CNS Spectrums. 2019;24(1):190-191.

20. Kumar B, Kuhad A, Kuhad A. Lumateperone: a new treatment approach for neuropsychiatric disorders. Drugs Today (Barc). 2018;54(12):713-719.

21. Davis RE, Vanover KE, Zhou Y, et al. ITI-007 demonstrates brain occupancy at serotonin 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin transporters using positron emission tomography in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(15):2863-72.

22. Björkholm C, Marcus MM, Konradsson-Geuken Å, et al. The novel antipsychotic drug brexpiprazole, alone and in combination with escitalopram, facilitates prefrontal glutamatergic transmission via a dopamine D1 receptor-dependent mechanism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):411-417.

23. Bai Y, Yang H, Chen G, et al. Acceptability of acute and maintenance pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(2):167-179.

24. Vyas P, Hwang BJ, Braši´c JR. An evaluation of lumateperone tosylate for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(2):139-145.

25. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160-168.

26. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):169-77.

Among patients with bipolar I or II disorder (BD I or II), major depressive episodes represent the predominant mood state when not euthymic, and are disproportionately associated with the functional disability of BD and its suicide risk.1 Long-term naturalistic studies of weekly mood states in patients with BD I or II found that the proportion of time spent depressed greatly exceeded that spent in a mixed, hypomanic, or manic state during >12 years of follow-up (Figure 12and Figure 23). In the 20th century, traditional antidepressants represented the sole option for management of bipolar depression despite concerns of manic switching or lack of efficacy.4,5 Efficacy concerns were subsequently confirmed by placebo-controlled studies, such as the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial, which found limited effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressants for bipolar depression.6 Comprehensive reviews of randomized controlled trials and observational studies documented the risk of mood cycling and manic switching, especially in patients with BD I, even if antidepressants were used in the presence of mood-stabilizing medications.7,8

Several newer antipsychotics have been FDA-approved for treating depressive episodes associated with BD (Table 1). Approval of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) in December 2003 for depressive episodes associated with BD I established that mechanisms exist which can effectively treat acute depressive episodes in patients with BD without an inordinate risk of mood instability. Subsequent approval of quetiapine in October 2006 for depression associated with BD I or II, lurasidone in June 2013, and cariprazine in May 2019 for major depression in BD I greatly expanded the options for management of acute bipolar depression. However, despite the array of molecules available, for certain patients these agents presented tolerability issues such as sedation, weight gain, akathisia, or parkinsonism that could hamper effective treatment.9 Safety and efficacy data in bipolar depression for adjunctive use with lithium or divalproex/valproate (VPA) also are lacking for quetiapine, OFC, and cariprazine.10,11 Moreover, despite the fact that BD II is as prevalent as BD I, and that patients with BD II have comparable rates of comorbidity, chronicity, disability, and suicidality,12 only quetiapine was approved for acute treatment of depression in patients with BD II. This omission is particularly problematic because the depressive episodes of BD II predominate over the time spent in hypomanic and cycling/mixed states (50.3% for depression vs 3.6% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined), much more than is seen with BD I (31.9% for depression vs 14.8% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined).2,3 The paucity of data for the use of newer antipsychotics in BD II depression presents a problem when patients cannot tolerate or refuse to consider quetiapine. This prevents clinicians from engaging in evidence-based efficacy discussions of other options, even if it is assumed that the tolerability profile for BD II depression patients may be similar to that seen when these agents are used for BD I depression.

Continue to: Table 1...

Lumateperone (Caplyta) is a novel oral antipsychotic initially approved in 2019 for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia. It was approved in December 2021 for the management of depression associated with BD I or II in adults as monotherapy or when used adjunctively with the mood stabilizers lithium or VPA (Table 2).13 Lumateperone possesses certain binding affinities not unlike those in other newer antipsychotics, including high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), low affinity for dopamine D2 receptors (Ki 32 nM), and low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).13,14 However, there are some distinguishing features: the ratio of 5HT2A receptor affinity to D2 affinity is 60, greater than that for other second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) such as risperidone (12), olanzapine (12.4) or aripiprazole (0.18).15 At steady state, D2 receptor occupancy remains <40%, and the corresponding rates of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)/akathisia differed by only 0.4% for lumateperone vs placebo in short-term adult clinical schizophrenia trials,13,16 by 0.2% for lumateperone vs placebo in the monotherapy BD depression study, and by 1.7% in the adjunctive BD depression study.13,17,18 Lumateperone also exhibited no clinically significant impact on metabolic measures or serum prolactin during the 4-week schizophrenia trials, with mean weight gain ≤1 kg for the 42 mg dose across all studies.19 This favorable tolerability profile for endocrine and metabolic adverse effects was also seen in the BD depression studies. Across the 2 BD depression monotherapy trials and the single adjunctive study, the only adverse reactions occurring in ≥5% of lumateperone-treated patients and more than twice the rate of placebo were somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth.13 There was also no single adverse reaction leading to discontinuation in the BD depression studies that occurred at a rate >2% in patients treated with lumateperone.13

In addition to the low risk of adverse events of all types, lumateperone has several pharmacologic features that distinguish it from other agents in its class. One unique aspect of lumateperone’s pharmacology is differential actions at presynaptic and postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors noted in preclinical assays, a property that may explain its ability to act as an antipsychotic despite low D2 receptor occupancy.16 Preclinical assays also predicted that lumateperone was likely to have antidepressant effects.15,19,20 Unlike every SGA except ziprasidone, lumateperone also possesses moderate binding affinity for serotonin transporters (SERT) (Ki 33 nM), with SERT occupancy of approximately 30% at 42 mg.21 Lumateperone facilitates dopamine D1-mediated neurotransmission, and this is associated with increased glutamate signaling in the prefrontal cortex and antidepressant actions.14,22 While the extent of SERT occupancy is significantly below the ≥80% SERT occupancy seen with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, it is hypothesized that near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor might act synergistically with modest 5HT reuptake inhibition and D1-mediated effects to promote the downstream glutamatergic effects that correlate with antidepressant activity (eg, changes in markers such as phosphorylation of glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits, potentiation of AMPA receptor-mediated transmission).15,22

Continue to: Clinical implications...

Clinical implications

The approval of lumateperone for both BD I and BD II depression, and for its use as monotherapy and for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA, satisfies several unmet needs for the management of acute major depressive episodes in patients with BD. Clinicians now have both safety and tolerability data to present to their bipolar spectrum patients regardless of subtype, and regardless of whether the patient requires mood stabilizer therapy. The tolerability advantages for lumateperone seen in schizophrenia trials were replicated in a diagnostic group that is very sensitive to D2-related adverse effects, and for whom any signal of clinically significant weight gain or sedation often represents an insuperable barrier to patient acceptance.23

Efficacy in adults with BD I or II depression.

The efficacy of lumateperone for major depressive episodes has been established in 2 pivotal, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in BD I or II patients: 1 monotherapy study,17 and 1 study when used adjunctively to lithium or VPA.18 The first study was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled monotherapy trial (study 404) in which 377 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode were randomized in a 1:1 manner to lumateperone 42 mg/d or placebo given once daily in the evening. Symptom entry criteria included a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall BD illness subscales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale–Bipolar Version Severity scale (CGI-BP-S) at screening and at baseline.17 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) at screening and at baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS. Several secondary efficacy measures were examined, including the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS), or remission (MADRS score ≤12), and differential changes in MADRS scores from baseline for BD I and BD II subgroups.17

The patient population was 58% female and 91% White, with 79.9% diagnosed as BD I and 20.1% as BD II. The least squares mean changes on the MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 were lumateperone 42 mg/d: -16.7 points; placebo: -12.1 points (P < .0001), and the effect size for this difference was moderate: 0.56. Secondary analyses indicated that 51.1% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 36.7% taking placebo met response criteria (P < .001), while 39.9% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 33.5% taking placebo met remission criteria (P = .018). Importantly, depression improvement was observed both in patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and in those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001).

The second pivotal trial (study 402) was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjunctive trial in which 528 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode despite treatment with lithium or VPA were randomized in a 1:1:1 manner to lumateperone 28 mg/d, lumateperone 42 mg/d, or placebo given once daily in the evening.18 Like the monotherapy trial, symptom entry criteria included a MADRS total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall illness CGI-BP-S subscales at screening and baseline.18 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the YMRS at screening and baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS for lumateperone 42 mg/d compared to placebo. Secondary efficacy measures included MADRS changes for lumateperone 28 mg/d and the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS) or remission (MADRS score ≤12).

The patient population was 58% female and 88% White, with 83.3% diagnosed as BD I, 16.7% diagnosed as BD II, and 28.6% treated with lithium vs 71.4% on VPA. The effect size for the difference in MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 for lumateperone 42 mg/d was 0.27 (P < .05), while that for the lumateperone 28 mg/d dose did not reach statistical significance. Secondary analyses indicated that response rates for lumateperone 28 mg/d and lumateperone 42 mg/d were significantly higher than for placebo (both P < .05). Response rates were placebo: 39%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 50%; and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 45%. Remission rates were similar at Day 43 in both lumateperone groups compared with placebo: placebo: 31%, lumateperone 28 mg/d: 31%, and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 28%.18 As of this writing, a secondary analysis by BD subtype has not yet been presented.

A third study examining lumateperone monotherapy failed to establish superiority of lumateperone over placebo (NCT02600494). The data regarding tolerability from that study were incorporated in product labeling describing adverse reactions.

Continue on to: Adverse reactions...

Adverse reactions

In the positive monotherapy trial, there were 376 patients in the modified intent-to-treat efficacy population to receive lumateperone (N = 188) or placebo (N = 188) with nearly identical completion rates in the active treatment and placebo cohorts: lumateperone, 88.8%; placebo, 88.3%.17 The proportion experiencing mania was low in both cohorts (lumateperone, 1.1%; placebo, 2.1%), and there was 1 case of hypomania in each group. One participant in the lumateperone group and 1 in the placebo group discontinued the study due to a serious adverse event of mania. There was no worsening of mania in either group as measured by mean change in the YMRS score. There was also no suicidal behavior in either cohort during the study. Pooling the 2 monotherapy trials, the adverse events that occurred at ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 13%, placebo: 3%), dizziness (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 4%), and nausea (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 3%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 1.3%, placebo: 1.1%.13 Mean weight change at Day 43 was +0.11 kg for lumateperone and +0.03 kg for placebo in the positive monotherapy trial.17 Moreover, compared to placebo, lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant. No patient exhibited a corrected QT interval >500 ms at any time, and increases ≥60 ms from baseline were similar between the lumateperone (n = 1, 0.6%) and placebo (n = 3, 1.8%) cohorts.

Complete safety and tolerability data for the adjunctive trial has not yet been published, but discontinuation rates due to treatment-emergent adverse effects for the 3 arms were: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 5.6%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 1.7%; and placebo: 1.7%. Overall, 81.4% of patients completed the trial, with only 1 serious adverse event (lithium toxicity) occurring in a patient taking lumateperone 42 mg/d. While this led to study discontinuation, it was not considered related to lumateperone exposure by the investigator. There was no worsening of mania in either lumateperone dosage group or the placebo cohort as measured by mean change in YMRS score: -1.2 for placebo, -1.4 for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and -1.6 for lumateperone 42 mg/d. Suicidal behavior was not observed in any group during treatment. The adverse events that occurred at rates ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone, 13%; placebo, 3%), dizziness (lumateperone, 11%; placebo, 2%), and nausea (lumateperone, 9%; placebo, 4%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone, 4.0%, placebo, 2.3%.13 Mean weight changes at Day 43 were +0.23 kg for placebo, +0.02 kg for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and 0.00 kg for lumateperone 42 mg/d.18 Compared to placebo, both doses of lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant.18

Lastly, the package insert notes that in an uncontrolled, open-label trial of lumateperone for up to 6 months in patients with BD depression, the mean weight change was -0.01 ± 3.1 kg at Day 175.13

Continue on to: Pharmacologic profile...

Pharmacologic profile

Lumateperone’s preclinical discovery program found an impact on markers associated with increased glutamatergic neurotransmission, properties that were predicted to yield antidepressant benefit.14,15,24 This is hypothesized to be based on the complex pharmacology of lumateperone, including dopamine D1 agonism, modest SERT occupancy, and near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor.15,22 Dopamine D2 affinity is modest (32 nM), and the D2 receptor occupancy at the 42 mg dose is low. These properties translate to rates of EPS in clinical studies of schizophrenia and BD that are close to that of placebo. Lumateperone has very high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), which also helps mitigate D2-related adverse effects and may be part of the therapeutic antidepressant mechanism. Underlying the tolerability profile is the low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).

Clinical considerations

Data from the lumateperone BD depression trials led to it being only the second agent approved for acute major depression in BD II patients, and the only agent which has approvals as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy for both BD subtypes. The monotherapy trial results substantiate that lumateperone was robustly effective regardless of BD subtype, with significant improvement in depressive symptoms experienced by patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001). Effect sizes in acute BD depression studies are much larger in monotherapy trials than in adjunctive trials, as the latter group represents patients who have already failed pretreatment with a mood stabilizer.25,26 In the lurasidone BD I depression trials, the effect size based on mean change in MADRS score over the course of 6 weeks was 0.51 in the monotherapy study compared to 0.34 when used adjunctively with lithium or VPA.25,26 In the lumateperone adjunctive study, the effect size for the difference in mean MADRS total score from baseline for lumateperone 42 mg/d, was 0.27 (P < .05). Subgroup analyses by BD subtype are not yet available for adjunctive use, but the data presented to FDA were sufficient to permit an indication for adjunctive use across both diagnostic groups.

The absence of clinically significant EPS, the minimal impact on metabolic or endocrine parameters, and the lack of a need for titration are all appealing properties. At the present there is only 1 marketed dose (42 mg capsules), so the package insert includes cautionary language regarding situations when a patient might encounter less drug exposure (concurrent use of cytochrome P450 [CYP] 3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure due to concurrent use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, as well as in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria (Child-Pugh B or C). These are not contraindications.

Unique properties of lumateperone include efficacy established as monotherapy for BD I and BD II patients, and efficacy for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA. Additionally, the extremely low rates of significant EPS and lack of clinically significant metabolic or endocrine adverse effects are unique properties of lumateperone.13

Why Rx? Reasons to prescribe lumateperone for adult BD depression patients include:

- data support efficacy for BD I and BD II patients, and for monotherapy or adjunctive use with lithium/VPA

- favorable tolerability profile, including no significant signal for EPS, endocrine or metabolic adverse effects, or QT prolongation

- no need for titration.

Dosing. There is only 1 dose available for lumateperone: 42 mg capsules (Table 3). As the dose cannot be modified, the package insert contains cautionary language regarding situations with less drug exposure (use of CYP3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure (use with moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria [Child-Pugh B or C]). These are not contraindications. Based on newer pharmacokinetic studies, lumateperone does not need to be dosed with food, and there is no clinically significant interaction with UGT1A4 inhibitors such as VPA.

Contraindications. The only contraindication is known hypersensitivity to lumateperone.

Bottom Line

Data support the efficacy of lumateperone for treating depressive episodes in adults with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, either as monotherapy or adjunctive to lithium or divalproex/valproate. Potential advantages of lumateperone for this indication include a favorable tolerability profile and no need for titration.

Among patients with bipolar I or II disorder (BD I or II), major depressive episodes represent the predominant mood state when not euthymic, and are disproportionately associated with the functional disability of BD and its suicide risk.1 Long-term naturalistic studies of weekly mood states in patients with BD I or II found that the proportion of time spent depressed greatly exceeded that spent in a mixed, hypomanic, or manic state during >12 years of follow-up (Figure 12and Figure 23). In the 20th century, traditional antidepressants represented the sole option for management of bipolar depression despite concerns of manic switching or lack of efficacy.4,5 Efficacy concerns were subsequently confirmed by placebo-controlled studies, such as the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial, which found limited effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressants for bipolar depression.6 Comprehensive reviews of randomized controlled trials and observational studies documented the risk of mood cycling and manic switching, especially in patients with BD I, even if antidepressants were used in the presence of mood-stabilizing medications.7,8

Several newer antipsychotics have been FDA-approved for treating depressive episodes associated with BD (Table 1). Approval of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) in December 2003 for depressive episodes associated with BD I established that mechanisms exist which can effectively treat acute depressive episodes in patients with BD without an inordinate risk of mood instability. Subsequent approval of quetiapine in October 2006 for depression associated with BD I or II, lurasidone in June 2013, and cariprazine in May 2019 for major depression in BD I greatly expanded the options for management of acute bipolar depression. However, despite the array of molecules available, for certain patients these agents presented tolerability issues such as sedation, weight gain, akathisia, or parkinsonism that could hamper effective treatment.9 Safety and efficacy data in bipolar depression for adjunctive use with lithium or divalproex/valproate (VPA) also are lacking for quetiapine, OFC, and cariprazine.10,11 Moreover, despite the fact that BD II is as prevalent as BD I, and that patients with BD II have comparable rates of comorbidity, chronicity, disability, and suicidality,12 only quetiapine was approved for acute treatment of depression in patients with BD II. This omission is particularly problematic because the depressive episodes of BD II predominate over the time spent in hypomanic and cycling/mixed states (50.3% for depression vs 3.6% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined), much more than is seen with BD I (31.9% for depression vs 14.8% for hypomania/cycling/mixed combined).2,3 The paucity of data for the use of newer antipsychotics in BD II depression presents a problem when patients cannot tolerate or refuse to consider quetiapine. This prevents clinicians from engaging in evidence-based efficacy discussions of other options, even if it is assumed that the tolerability profile for BD II depression patients may be similar to that seen when these agents are used for BD I depression.

Continue to: Table 1...

Lumateperone (Caplyta) is a novel oral antipsychotic initially approved in 2019 for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia. It was approved in December 2021 for the management of depression associated with BD I or II in adults as monotherapy or when used adjunctively with the mood stabilizers lithium or VPA (Table 2).13 Lumateperone possesses certain binding affinities not unlike those in other newer antipsychotics, including high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), low affinity for dopamine D2 receptors (Ki 32 nM), and low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).13,14 However, there are some distinguishing features: the ratio of 5HT2A receptor affinity to D2 affinity is 60, greater than that for other second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) such as risperidone (12), olanzapine (12.4) or aripiprazole (0.18).15 At steady state, D2 receptor occupancy remains <40%, and the corresponding rates of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)/akathisia differed by only 0.4% for lumateperone vs placebo in short-term adult clinical schizophrenia trials,13,16 by 0.2% for lumateperone vs placebo in the monotherapy BD depression study, and by 1.7% in the adjunctive BD depression study.13,17,18 Lumateperone also exhibited no clinically significant impact on metabolic measures or serum prolactin during the 4-week schizophrenia trials, with mean weight gain ≤1 kg for the 42 mg dose across all studies.19 This favorable tolerability profile for endocrine and metabolic adverse effects was also seen in the BD depression studies. Across the 2 BD depression monotherapy trials and the single adjunctive study, the only adverse reactions occurring in ≥5% of lumateperone-treated patients and more than twice the rate of placebo were somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth.13 There was also no single adverse reaction leading to discontinuation in the BD depression studies that occurred at a rate >2% in patients treated with lumateperone.13

In addition to the low risk of adverse events of all types, lumateperone has several pharmacologic features that distinguish it from other agents in its class. One unique aspect of lumateperone’s pharmacology is differential actions at presynaptic and postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors noted in preclinical assays, a property that may explain its ability to act as an antipsychotic despite low D2 receptor occupancy.16 Preclinical assays also predicted that lumateperone was likely to have antidepressant effects.15,19,20 Unlike every SGA except ziprasidone, lumateperone also possesses moderate binding affinity for serotonin transporters (SERT) (Ki 33 nM), with SERT occupancy of approximately 30% at 42 mg.21 Lumateperone facilitates dopamine D1-mediated neurotransmission, and this is associated with increased glutamate signaling in the prefrontal cortex and antidepressant actions.14,22 While the extent of SERT occupancy is significantly below the ≥80% SERT occupancy seen with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, it is hypothesized that near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor might act synergistically with modest 5HT reuptake inhibition and D1-mediated effects to promote the downstream glutamatergic effects that correlate with antidepressant activity (eg, changes in markers such as phosphorylation of glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits, potentiation of AMPA receptor-mediated transmission).15,22

Continue to: Clinical implications...

Clinical implications

The approval of lumateperone for both BD I and BD II depression, and for its use as monotherapy and for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA, satisfies several unmet needs for the management of acute major depressive episodes in patients with BD. Clinicians now have both safety and tolerability data to present to their bipolar spectrum patients regardless of subtype, and regardless of whether the patient requires mood stabilizer therapy. The tolerability advantages for lumateperone seen in schizophrenia trials were replicated in a diagnostic group that is very sensitive to D2-related adverse effects, and for whom any signal of clinically significant weight gain or sedation often represents an insuperable barrier to patient acceptance.23

Efficacy in adults with BD I or II depression.

The efficacy of lumateperone for major depressive episodes has been established in 2 pivotal, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in BD I or II patients: 1 monotherapy study,17 and 1 study when used adjunctively to lithium or VPA.18 The first study was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled monotherapy trial (study 404) in which 377 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode were randomized in a 1:1 manner to lumateperone 42 mg/d or placebo given once daily in the evening. Symptom entry criteria included a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall BD illness subscales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale–Bipolar Version Severity scale (CGI-BP-S) at screening and at baseline.17 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) at screening and at baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS. Several secondary efficacy measures were examined, including the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS), or remission (MADRS score ≤12), and differential changes in MADRS scores from baseline for BD I and BD II subgroups.17

The patient population was 58% female and 91% White, with 79.9% diagnosed as BD I and 20.1% as BD II. The least squares mean changes on the MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 were lumateperone 42 mg/d: -16.7 points; placebo: -12.1 points (P < .0001), and the effect size for this difference was moderate: 0.56. Secondary analyses indicated that 51.1% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 36.7% taking placebo met response criteria (P < .001), while 39.9% of those taking lumateperone 42 mg/d and 33.5% taking placebo met remission criteria (P = .018). Importantly, depression improvement was observed both in patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and in those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001).

The second pivotal trial (study 402) was a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjunctive trial in which 528 patients age 18 to 75 with BD I or BD II experiencing a major depressive episode despite treatment with lithium or VPA were randomized in a 1:1:1 manner to lumateperone 28 mg/d, lumateperone 42 mg/d, or placebo given once daily in the evening.18 Like the monotherapy trial, symptom entry criteria included a MADRS total score ≥20, and scores ≥4 on the depression and overall illness CGI-BP-S subscales at screening and baseline.18 Study entry also required a score ≤12 on the YMRS at screening and baseline. The duration of the major depressive episode must have been ≥2 weeks but <6 months before screening, with symptoms causing clinically significant distress or functional impairment. The primary outcome measure was change from baseline in MADRS for lumateperone 42 mg/d compared to placebo. Secondary efficacy measures included MADRS changes for lumateperone 28 mg/d and the proportion of patients meeting criteria for treatment response (≥50% decrease in MADRS) or remission (MADRS score ≤12).

The patient population was 58% female and 88% White, with 83.3% diagnosed as BD I, 16.7% diagnosed as BD II, and 28.6% treated with lithium vs 71.4% on VPA. The effect size for the difference in MADRS total score from baseline to Day 43 for lumateperone 42 mg/d was 0.27 (P < .05), while that for the lumateperone 28 mg/d dose did not reach statistical significance. Secondary analyses indicated that response rates for lumateperone 28 mg/d and lumateperone 42 mg/d were significantly higher than for placebo (both P < .05). Response rates were placebo: 39%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 50%; and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 45%. Remission rates were similar at Day 43 in both lumateperone groups compared with placebo: placebo: 31%, lumateperone 28 mg/d: 31%, and lumateperone 42 mg/d: 28%.18 As of this writing, a secondary analysis by BD subtype has not yet been presented.

A third study examining lumateperone monotherapy failed to establish superiority of lumateperone over placebo (NCT02600494). The data regarding tolerability from that study were incorporated in product labeling describing adverse reactions.

Continue on to: Adverse reactions...

Adverse reactions

In the positive monotherapy trial, there were 376 patients in the modified intent-to-treat efficacy population to receive lumateperone (N = 188) or placebo (N = 188) with nearly identical completion rates in the active treatment and placebo cohorts: lumateperone, 88.8%; placebo, 88.3%.17 The proportion experiencing mania was low in both cohorts (lumateperone, 1.1%; placebo, 2.1%), and there was 1 case of hypomania in each group. One participant in the lumateperone group and 1 in the placebo group discontinued the study due to a serious adverse event of mania. There was no worsening of mania in either group as measured by mean change in the YMRS score. There was also no suicidal behavior in either cohort during the study. Pooling the 2 monotherapy trials, the adverse events that occurred at ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 13%, placebo: 3%), dizziness (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 4%), and nausea (lumateperone 42 mg/d: 8%, placebo: 3%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 1.3%, placebo: 1.1%.13 Mean weight change at Day 43 was +0.11 kg for lumateperone and +0.03 kg for placebo in the positive monotherapy trial.17 Moreover, compared to placebo, lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant. No patient exhibited a corrected QT interval >500 ms at any time, and increases ≥60 ms from baseline were similar between the lumateperone (n = 1, 0.6%) and placebo (n = 3, 1.8%) cohorts.

Complete safety and tolerability data for the adjunctive trial has not yet been published, but discontinuation rates due to treatment-emergent adverse effects for the 3 arms were: lumateperone 42 mg/d: 5.6%; lumateperone 28 mg/d: 1.7%; and placebo: 1.7%. Overall, 81.4% of patients completed the trial, with only 1 serious adverse event (lithium toxicity) occurring in a patient taking lumateperone 42 mg/d. While this led to study discontinuation, it was not considered related to lumateperone exposure by the investigator. There was no worsening of mania in either lumateperone dosage group or the placebo cohort as measured by mean change in YMRS score: -1.2 for placebo, -1.4 for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and -1.6 for lumateperone 42 mg/d. Suicidal behavior was not observed in any group during treatment. The adverse events that occurred at rates ≥5% in lumateperone-treated patients and at more than twice the rate of the placebo group were somnolence/sedation (lumateperone, 13%; placebo, 3%), dizziness (lumateperone, 11%; placebo, 2%), and nausea (lumateperone, 9%; placebo, 4%).13 Rates of EPS were low for both groups: lumateperone, 4.0%, placebo, 2.3%.13 Mean weight changes at Day 43 were +0.23 kg for placebo, +0.02 kg for lumateperone 28 mg/d, and 0.00 kg for lumateperone 42 mg/d.18 Compared to placebo, both doses of lumateperone exhibited comparable effects on serum prolactin and all metabolic parameters, including fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and fasting lipids, none of which were clinically significant.18

Lastly, the package insert notes that in an uncontrolled, open-label trial of lumateperone for up to 6 months in patients with BD depression, the mean weight change was -0.01 ± 3.1 kg at Day 175.13

Continue on to: Pharmacologic profile...

Pharmacologic profile

Lumateperone’s preclinical discovery program found an impact on markers associated with increased glutamatergic neurotransmission, properties that were predicted to yield antidepressant benefit.14,15,24 This is hypothesized to be based on the complex pharmacology of lumateperone, including dopamine D1 agonism, modest SERT occupancy, and near saturation of the 5HT2A receptor.15,22 Dopamine D2 affinity is modest (32 nM), and the D2 receptor occupancy at the 42 mg dose is low. These properties translate to rates of EPS in clinical studies of schizophrenia and BD that are close to that of placebo. Lumateperone has very high affinity for serotonin 5HT2A receptors (Ki 0.54 nM), which also helps mitigate D2-related adverse effects and may be part of the therapeutic antidepressant mechanism. Underlying the tolerability profile is the low affinity for alpha 1-adrenergic receptors (Ki 73 nM), muscarinic and histaminergic receptors (Ki >100 nM for both).

Clinical considerations

Data from the lumateperone BD depression trials led to it being only the second agent approved for acute major depression in BD II patients, and the only agent which has approvals as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy for both BD subtypes. The monotherapy trial results substantiate that lumateperone was robustly effective regardless of BD subtype, with significant improvement in depressive symptoms experienced by patients with BD I (effect size 0.49, P < .0001) and those with BD II (effect size 0.81, P < .001). Effect sizes in acute BD depression studies are much larger in monotherapy trials than in adjunctive trials, as the latter group represents patients who have already failed pretreatment with a mood stabilizer.25,26 In the lurasidone BD I depression trials, the effect size based on mean change in MADRS score over the course of 6 weeks was 0.51 in the monotherapy study compared to 0.34 when used adjunctively with lithium or VPA.25,26 In the lumateperone adjunctive study, the effect size for the difference in mean MADRS total score from baseline for lumateperone 42 mg/d, was 0.27 (P < .05). Subgroup analyses by BD subtype are not yet available for adjunctive use, but the data presented to FDA were sufficient to permit an indication for adjunctive use across both diagnostic groups.

The absence of clinically significant EPS, the minimal impact on metabolic or endocrine parameters, and the lack of a need for titration are all appealing properties. At the present there is only 1 marketed dose (42 mg capsules), so the package insert includes cautionary language regarding situations when a patient might encounter less drug exposure (concurrent use of cytochrome P450 [CYP] 3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure due to concurrent use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, as well as in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria (Child-Pugh B or C). These are not contraindications.

Unique properties of lumateperone include efficacy established as monotherapy for BD I and BD II patients, and efficacy for adjunctive use with lithium or VPA. Additionally, the extremely low rates of significant EPS and lack of clinically significant metabolic or endocrine adverse effects are unique properties of lumateperone.13

Why Rx? Reasons to prescribe lumateperone for adult BD depression patients include:

- data support efficacy for BD I and BD II patients, and for monotherapy or adjunctive use with lithium/VPA

- favorable tolerability profile, including no significant signal for EPS, endocrine or metabolic adverse effects, or QT prolongation

- no need for titration.

Dosing. There is only 1 dose available for lumateperone: 42 mg capsules (Table 3). As the dose cannot be modified, the package insert contains cautionary language regarding situations with less drug exposure (use of CYP3A4 inducers), or greater drug exposure (use with moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment as defined by Child-Pugh Criteria [Child-Pugh B or C]). These are not contraindications. Based on newer pharmacokinetic studies, lumateperone does not need to be dosed with food, and there is no clinically significant interaction with UGT1A4 inhibitors such as VPA.

Contraindications. The only contraindication is known hypersensitivity to lumateperone.

Bottom Line

Data support the efficacy of lumateperone for treating depressive episodes in adults with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, either as monotherapy or adjunctive to lithium or divalproex/valproate. Potential advantages of lumateperone for this indication include a favorable tolerability profile and no need for titration.

1. Malhi GS, Bell E, Boyce P, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(8):805-821.

2. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

3. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

4. Post RM. Treatment of bipolar depression: evolving recommendations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):11-33.

5. Pacchiarotti I, Verdolini N. Antidepressants in bipolar II depression: yes and no. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2021;47:48-50.

6. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711-1722.

7. Allain N, Leven C, Falissard B, et al. Manic switches induced by antidepressants: an umbrella review comparing randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):106-116.

8. Gitlin MJ. Antidepressants in bipolar depression: an enduring controversy. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):25.

9. Verdolini N, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Del Matto L, et al. Long-term treatment of bipolar disorder type I: a systematic and critical review of clinical guidelines with derived practice algorithms. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(4):324-340.

10. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017), part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):180-195.

11. Vraylar [package insert]. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2019.

12. Chakrabarty T, Hadijpavlou G, Bond DJ, et al. Bipolar II disorder in context: a review of its epidemiology, disability and economic burden. In: Parker G. Bipolar II Disorder: Modelling, Measuring and Managing. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2019:49-59.

13. Caplyta [package insert]. New York, NY: Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc.; 2021.

14. Davis RE, Correll CU. ITI-007 in the treatment of schizophrenia: from novel pharmacology to clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(6):601-614.

15. Snyder GL, Vanover KE, Zhu H, et al. Functional profile of a novel modulator of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate neurotransmission. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232:605-621.

16. Vanover KE, Davis RE, Zhou Y, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy of lumateperone (ITI-007): a positron emission tomography study in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):598-605.

17. Calabrese JR, Durgam S, Satlin A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lumateperone for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2021;178(12):1098-1106.

18. Yatham LN, et al. Adjunctive lumateperone (ITI-007) in the treatment of bipolar depression: results from a randomized clinical trial. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting. May 1-3, 2021; virtual conference.

19. Vanover K, Glass S, Kozauer S, et al. 30 Lumateperone (ITI-007) for the treatment of schizophrenia: overview of placebo-controlled clinical trials and an open-label safety switching study. CNS Spectrums. 2019;24(1):190-191.

20. Kumar B, Kuhad A, Kuhad A. Lumateperone: a new treatment approach for neuropsychiatric disorders. Drugs Today (Barc). 2018;54(12):713-719.

21. Davis RE, Vanover KE, Zhou Y, et al. ITI-007 demonstrates brain occupancy at serotonin 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin transporters using positron emission tomography in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(15):2863-72.

22. Björkholm C, Marcus MM, Konradsson-Geuken Å, et al. The novel antipsychotic drug brexpiprazole, alone and in combination with escitalopram, facilitates prefrontal glutamatergic transmission via a dopamine D1 receptor-dependent mechanism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):411-417.

23. Bai Y, Yang H, Chen G, et al. Acceptability of acute and maintenance pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(2):167-179.

24. Vyas P, Hwang BJ, Braši´c JR. An evaluation of lumateperone tosylate for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(2):139-145.

25. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160-168.

26. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):169-77.

1. Malhi GS, Bell E, Boyce P, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(8):805-821.

2. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

3. Judd LL, Akishal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

4. Post RM. Treatment of bipolar depression: evolving recommendations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):11-33.

5. Pacchiarotti I, Verdolini N. Antidepressants in bipolar II depression: yes and no. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2021;47:48-50.

6. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711-1722.

7. Allain N, Leven C, Falissard B, et al. Manic switches induced by antidepressants: an umbrella review comparing randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):106-116.

8. Gitlin MJ. Antidepressants in bipolar depression: an enduring controversy. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):25.

9. Verdolini N, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Del Matto L, et al. Long-term treatment of bipolar disorder type I: a systematic and critical review of clinical guidelines with derived practice algorithms. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(4):324-340.

10. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017), part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):180-195.

11. Vraylar [package insert]. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2019.

12. Chakrabarty T, Hadijpavlou G, Bond DJ, et al. Bipolar II disorder in context: a review of its epidemiology, disability and economic burden. In: Parker G. Bipolar II Disorder: Modelling, Measuring and Managing. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2019:49-59.

13. Caplyta [package insert]. New York, NY: Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc.; 2021.

14. Davis RE, Correll CU. ITI-007 in the treatment of schizophrenia: from novel pharmacology to clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(6):601-614.

15. Snyder GL, Vanover KE, Zhu H, et al. Functional profile of a novel modulator of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate neurotransmission. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232:605-621.

16. Vanover KE, Davis RE, Zhou Y, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy of lumateperone (ITI-007): a positron emission tomography study in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):598-605.

17. Calabrese JR, Durgam S, Satlin A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lumateperone for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2021;178(12):1098-1106.

18. Yatham LN, et al. Adjunctive lumateperone (ITI-007) in the treatment of bipolar depression: results from a randomized clinical trial. Poster presented at: American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting. May 1-3, 2021; virtual conference.

19. Vanover K, Glass S, Kozauer S, et al. 30 Lumateperone (ITI-007) for the treatment of schizophrenia: overview of placebo-controlled clinical trials and an open-label safety switching study. CNS Spectrums. 2019;24(1):190-191.

20. Kumar B, Kuhad A, Kuhad A. Lumateperone: a new treatment approach for neuropsychiatric disorders. Drugs Today (Barc). 2018;54(12):713-719.

21. Davis RE, Vanover KE, Zhou Y, et al. ITI-007 demonstrates brain occupancy at serotonin 5-HT2A and dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin transporters using positron emission tomography in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(15):2863-72.

22. Björkholm C, Marcus MM, Konradsson-Geuken Å, et al. The novel antipsychotic drug brexpiprazole, alone and in combination with escitalopram, facilitates prefrontal glutamatergic transmission via a dopamine D1 receptor-dependent mechanism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):411-417.

23. Bai Y, Yang H, Chen G, et al. Acceptability of acute and maintenance pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(2):167-179.

24. Vyas P, Hwang BJ, Braši´c JR. An evaluation of lumateperone tosylate for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(2):139-145.

25. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160-168.

26. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):169-77.

When is your patient a candidate for ECT?

LAS VEGAS – How do you know when a patient is a candidate for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)?

In the opinion of Mark S. George, MD, it depends on the level of treatment resistance, other treatments the person may be receiving for severe depression or bipolar disorder, and the level of acuity.

“Acute ECT is also useful for catatonia that does not resolve with benzodiazepines, and it also works well for acute suicidality,” Dr. George, distinguished professor of psychiatry, radiology, and neurology at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “The other reason you would go straight to ECT would be if someone has had good prior ECT response.”

It is lifesaving. Some studies suggests that ECT is effective in Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia. Antidepressant effects generally take 2-3 weeks, but quicker responses are sometimes seen, especially in patients with bipolar depression.”

In the past 20 years of research studies involving ECT, investigators have discovered that a generalized seizure of adequate duration is necessary for adequate antidepressant effects; reduced therapeutic effects are seen with parietal placement, meaning that proper scalp placement matters; a dose titration over the 12 treatments improves efficacy, and smaller pulse widths are more effective and may result in fewer toxic side effects. “ECT is still relatively spatially crude compared with the other brain stimulation treatments,” said Dr. George, editor-in-chief of Brain Stimulation. “It’s also invasive, requiring repeated anesthesia, and sometimes has possible side effects including impacts on short-term memory.”

An emerging adjunct to ECT is cervical invasive vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy, in which mild electrical pulses applied to the left vagus nerve in the neck send signals to the brain. “Surgeons wrap a wire around the vagus nerve and connect the wire to a generator which is embedded in the chest wall,” Dr. George explained. “The generator sends out a signal through the vagus nerve intermittently. You can program how it does that.”

A device from LivaNova known as the VNS Pulse Model 102 Generator was granted clearance for depression based on a comparative study, but in the absence of class I evidence. The generator is about the size of a quarter, is embedded under the skin, and its battery lasts for 8-10 years. “Patients are given a static magnet to use to turn the device off if they’re having side effects, as a safety precaution,” said Dr. George, a staff physician at the Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center in Charleston. “The side effects are mainly stimulation-based and typically decrease over time. There is a low rate of treatment discontinuation and no signal for treatment-related emergence of suicidal ideation/behavior. Sometimes you can get emergent mania or hypermania, but it’s rare. It’s pretty safe, but the insurance companies have been very slow to pay. You only get about 30% remission, this takes several months to years to achieve, and there’s no way to tell who’s going to respond before you place the device.”