User login

High antipsychotic switch rates suggest ‘suboptimal’ prescribing for first-episode psychosis

In a large-scale, real-world analysis of U.K. prescribing patterns, researchers found more than two-thirds of patients who received antipsychotics for FEP switched medication, and almost half switched drugs three times.

Although this is “one of the largest real-world studies examining antipsychotic treatment strategies,” it reflects findings from previous, smaller studies showing “antipsychotic switching in first episode psychosis is high,” said study investigator Aimee Brinn, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London.

This may reflect reports of poor efficacy and suggests that first-line prescribing is “suboptimal,” Ms. Brinn noted. In addition, olanzapine remains the most popular antipsychotic for prescribing despite recent guidelines indicating it is “not ideal ... due to its dangerous metabolic side effects,” she added.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2022.

Real-world data

The response to, and tolerability of, antipsychotics differs between patients with FEP; and prescribing patterns “reflect clinician and patient-led decisionmaking,” Ms. Brinn told meeting attendees.

Since randomized controlled trials “do not necessarily reflect prescribing practice in real-world clinical settings,” the researchers gathered data from a large mental health care electronic health record dataset.

The investigators examined records from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), which has a catchment area of 1.2 million individuals across four boroughs of London. The group sees approximately 37,500 active patients per week.

The team used the Clinical Interactive Record Search tool to extract data on 2,309 adults with FEP who received care from a SLaM early intervention in psychosis service between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2019.

They found that 12 different antipsychotics were prescribed as first-line treatment. The most common were olanzapine (43.9%), risperidone (24.7%), and aripiprazole (19.9%).

Results showed that over 81,969.5 person-years of follow-up, at a minimum of 24 months per patient, 68.8% had an antipsychotic switch. The most common first treatment switch, in 17.9% of patients, was from olanzapine to aripiprazole.

Of patients who switched to aripiprazole, 48.4% stayed on the drug, 26% switched back to olanzapine, and 25.6% received other treatment. Overall, 44.7% of patients switched medication at least three times.

Among patients with FEP who did not switch, 42.2% were prescribed olanzapine, 26.2% risperidone, 23.3% aripiprazole, 5.6% quetiapine, and 2.7% amisulpride.

During the post-presentation discussion, Ms. Brinn was asked whether the high rate of first-line olanzapine prescribing could be because patients started treatment as inpatients and were then switched once they were moved to community care.

“We found that a lot of patients would be prescribed olanzapine for around 7 days at the start of their prescription and then switch,” Ms. Brinn said, adding it is “likely” they started as inpatients. The investigators are currently examining the differences between inpatient and outpatient prescriptions to verify whether this is indeed the case, she added.

‘Pulling out the big guns too fast?’

Commenting on the findings, Thomas W. Sedlak, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said the study raises a “number of questions.”

Both olanzapine and risperidone “tend to have higher treatment effect improvements than aripiprazole, so it’s curious that a switch to aripiprazole was common,” said Dr. Sedlak, who was not involved with the research.

“Are we pulling out the ‘big guns’ too fast, or inappropriately, especially as olanzapine and risperidone carry greater risk of weight gain?” he asked. In addition, “now that olanzapine is available with samidorphan to mitigate weight gain, will that shape future patterns, if it can be paid for?”

Dr. Sedlak noted it was unclear why olanzapine was chosen so often as first-line treatment in the study and agreed it is “possible that hospitalized patients had been prescribed a ‘stronger’ medication like olanzapine compared to never-hospitalized patients.”

He also underlined that it is “not clear if patients in this FEP program are representative of all FEP patients.”

“For instance, if the program is well known to inpatient hospital social workers, then the program might be disproportionately filled with patients who have had more severe symptoms,” Dr. Sedlak said.

The study was supported by Janssen-Cilag. The investigators and Dr. Sedlak have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large-scale, real-world analysis of U.K. prescribing patterns, researchers found more than two-thirds of patients who received antipsychotics for FEP switched medication, and almost half switched drugs three times.

Although this is “one of the largest real-world studies examining antipsychotic treatment strategies,” it reflects findings from previous, smaller studies showing “antipsychotic switching in first episode psychosis is high,” said study investigator Aimee Brinn, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London.

This may reflect reports of poor efficacy and suggests that first-line prescribing is “suboptimal,” Ms. Brinn noted. In addition, olanzapine remains the most popular antipsychotic for prescribing despite recent guidelines indicating it is “not ideal ... due to its dangerous metabolic side effects,” she added.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2022.

Real-world data

The response to, and tolerability of, antipsychotics differs between patients with FEP; and prescribing patterns “reflect clinician and patient-led decisionmaking,” Ms. Brinn told meeting attendees.

Since randomized controlled trials “do not necessarily reflect prescribing practice in real-world clinical settings,” the researchers gathered data from a large mental health care electronic health record dataset.

The investigators examined records from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), which has a catchment area of 1.2 million individuals across four boroughs of London. The group sees approximately 37,500 active patients per week.

The team used the Clinical Interactive Record Search tool to extract data on 2,309 adults with FEP who received care from a SLaM early intervention in psychosis service between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2019.

They found that 12 different antipsychotics were prescribed as first-line treatment. The most common were olanzapine (43.9%), risperidone (24.7%), and aripiprazole (19.9%).

Results showed that over 81,969.5 person-years of follow-up, at a minimum of 24 months per patient, 68.8% had an antipsychotic switch. The most common first treatment switch, in 17.9% of patients, was from olanzapine to aripiprazole.

Of patients who switched to aripiprazole, 48.4% stayed on the drug, 26% switched back to olanzapine, and 25.6% received other treatment. Overall, 44.7% of patients switched medication at least three times.

Among patients with FEP who did not switch, 42.2% were prescribed olanzapine, 26.2% risperidone, 23.3% aripiprazole, 5.6% quetiapine, and 2.7% amisulpride.

During the post-presentation discussion, Ms. Brinn was asked whether the high rate of first-line olanzapine prescribing could be because patients started treatment as inpatients and were then switched once they were moved to community care.

“We found that a lot of patients would be prescribed olanzapine for around 7 days at the start of their prescription and then switch,” Ms. Brinn said, adding it is “likely” they started as inpatients. The investigators are currently examining the differences between inpatient and outpatient prescriptions to verify whether this is indeed the case, she added.

‘Pulling out the big guns too fast?’

Commenting on the findings, Thomas W. Sedlak, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said the study raises a “number of questions.”

Both olanzapine and risperidone “tend to have higher treatment effect improvements than aripiprazole, so it’s curious that a switch to aripiprazole was common,” said Dr. Sedlak, who was not involved with the research.

“Are we pulling out the ‘big guns’ too fast, or inappropriately, especially as olanzapine and risperidone carry greater risk of weight gain?” he asked. In addition, “now that olanzapine is available with samidorphan to mitigate weight gain, will that shape future patterns, if it can be paid for?”

Dr. Sedlak noted it was unclear why olanzapine was chosen so often as first-line treatment in the study and agreed it is “possible that hospitalized patients had been prescribed a ‘stronger’ medication like olanzapine compared to never-hospitalized patients.”

He also underlined that it is “not clear if patients in this FEP program are representative of all FEP patients.”

“For instance, if the program is well known to inpatient hospital social workers, then the program might be disproportionately filled with patients who have had more severe symptoms,” Dr. Sedlak said.

The study was supported by Janssen-Cilag. The investigators and Dr. Sedlak have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large-scale, real-world analysis of U.K. prescribing patterns, researchers found more than two-thirds of patients who received antipsychotics for FEP switched medication, and almost half switched drugs three times.

Although this is “one of the largest real-world studies examining antipsychotic treatment strategies,” it reflects findings from previous, smaller studies showing “antipsychotic switching in first episode psychosis is high,” said study investigator Aimee Brinn, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London.

This may reflect reports of poor efficacy and suggests that first-line prescribing is “suboptimal,” Ms. Brinn noted. In addition, olanzapine remains the most popular antipsychotic for prescribing despite recent guidelines indicating it is “not ideal ... due to its dangerous metabolic side effects,” she added.

The findings were presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2022.

Real-world data

The response to, and tolerability of, antipsychotics differs between patients with FEP; and prescribing patterns “reflect clinician and patient-led decisionmaking,” Ms. Brinn told meeting attendees.

Since randomized controlled trials “do not necessarily reflect prescribing practice in real-world clinical settings,” the researchers gathered data from a large mental health care electronic health record dataset.

The investigators examined records from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), which has a catchment area of 1.2 million individuals across four boroughs of London. The group sees approximately 37,500 active patients per week.

The team used the Clinical Interactive Record Search tool to extract data on 2,309 adults with FEP who received care from a SLaM early intervention in psychosis service between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2019.

They found that 12 different antipsychotics were prescribed as first-line treatment. The most common were olanzapine (43.9%), risperidone (24.7%), and aripiprazole (19.9%).

Results showed that over 81,969.5 person-years of follow-up, at a minimum of 24 months per patient, 68.8% had an antipsychotic switch. The most common first treatment switch, in 17.9% of patients, was from olanzapine to aripiprazole.

Of patients who switched to aripiprazole, 48.4% stayed on the drug, 26% switched back to olanzapine, and 25.6% received other treatment. Overall, 44.7% of patients switched medication at least three times.

Among patients with FEP who did not switch, 42.2% were prescribed olanzapine, 26.2% risperidone, 23.3% aripiprazole, 5.6% quetiapine, and 2.7% amisulpride.

During the post-presentation discussion, Ms. Brinn was asked whether the high rate of first-line olanzapine prescribing could be because patients started treatment as inpatients and were then switched once they were moved to community care.

“We found that a lot of patients would be prescribed olanzapine for around 7 days at the start of their prescription and then switch,” Ms. Brinn said, adding it is “likely” they started as inpatients. The investigators are currently examining the differences between inpatient and outpatient prescriptions to verify whether this is indeed the case, she added.

‘Pulling out the big guns too fast?’

Commenting on the findings, Thomas W. Sedlak, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said the study raises a “number of questions.”

Both olanzapine and risperidone “tend to have higher treatment effect improvements than aripiprazole, so it’s curious that a switch to aripiprazole was common,” said Dr. Sedlak, who was not involved with the research.

“Are we pulling out the ‘big guns’ too fast, or inappropriately, especially as olanzapine and risperidone carry greater risk of weight gain?” he asked. In addition, “now that olanzapine is available with samidorphan to mitigate weight gain, will that shape future patterns, if it can be paid for?”

Dr. Sedlak noted it was unclear why olanzapine was chosen so often as first-line treatment in the study and agreed it is “possible that hospitalized patients had been prescribed a ‘stronger’ medication like olanzapine compared to never-hospitalized patients.”

He also underlined that it is “not clear if patients in this FEP program are representative of all FEP patients.”

“For instance, if the program is well known to inpatient hospital social workers, then the program might be disproportionately filled with patients who have had more severe symptoms,” Dr. Sedlak said.

The study was supported by Janssen-Cilag. The investigators and Dr. Sedlak have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SIRS 2022

New combination med for severe mental illness tied to less weight gain

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SIRS 2022

FDA okays first sublingual med for agitation in serious mental illness

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The importance of treating insomnia in psychiatric illness

Data suggests this symptom, defined as chronic sleep onset and/or sleep continuity problems associated with impaired daytime functioning, is common in psychiatric illnesses, and can worsen their course.2

The incidence of psychiatric illness in patients with insomnia is estimated at near 50%, with the highest rates found in mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, as well as anxiety disorders.3 In patients with diagnosed major depressive disorder, insomnia rates can approach 90%.4-6

Insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for development of mental illness, including doubling the risk of major depressive disorder and tripling the risk of any depressive or anxiety disorder.7,8 It can also significantly increase the risk of alcohol abuse and psychosis.8

Sleep disturbances can worsen symptoms of diagnosed mental illness, including substance abuse, mood and psychotic disorders.9-10 In one study, nearly 75% of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar spectrum disorder had at least one type of sleep disturbance (insomnia, hypersomnia, or delayed sleep phase).10 This was almost twice the rate in healthy controls. Importantly, compared with well-rested subjects with mental illness in this study, sleep-disordered participants had higher rates of negative and depressive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, as well as significantly lower function via the global assessment of functioning.11,12

Additional data suggests simply being awake during the night (00:00-05:59) elevates risk of suicide. The mean incident rate of completed suicide in one study was a striking four times the rate noted during daytime hours (06:00-23:59 ) (P < .001).13

Although insomnia symptoms can resolve after relief from a particular life stressor, as many as half of patients with more severe symptoms develop a chronic course.14 This then leads to an extended use of many types of sedative-hypnotics designed and studied primarily for short-term use.15 In a survey reviewing national use of prescription drugs for insomnia, as many as 20% of individuals use a medication to target insomnia in a given month.16

Fortunately, despite the many challenges posed by COVID-19, particularly for those with psychiatric illness and limited access to care, telehealth has become more readily available. Additionally, digital versions of evidence-based treatments specifically for sleep problems, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), are regularly being developed.

The benefits of CBT-I have been demonstrated repeatedly and it is recommended as the first line treatment for insomnia by the Clinical Guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.17-21 Studies suggest benefits persist long-term, even after completing the therapy sessions, which differ in durability from medication choices.18

One group that may be particularly suited for treatment with CBT-I is women with insomnia during pregnancy or the postpartum period. In these women, options for treatment may be limited by risk of medication during breastfeeding, as well as difficulty traveling to a physician’s or therapist’s office to receive psychotherapy. However, two recent studies evaluated the use of digital CBT-I to treat insomnia during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, respectively.22-23

In both studies,the same group of women with insomnia diagnosed during pregnancy were given six weekly 20-minute sessions of digital CBT-I or standard treatment for insomnia, including medication and psychotherapy per their usual provider.

By study end, the pregnant women receiving the CBT-I intervention not only had significantly improved severity of insomnia, they also experienced improved depression and anxiety symptoms, and a decrease in the use of prescription or over-the-counter sleep aides, compared with the standard treatment group, lowering the fetal exposure to medication during pregnancy.22

In the more recent study, the same group was followed for 6 months post partum.23 Results were again notable, with the women who received CBT-I reporting significantly less insomnia, as well as significantly lower rates of probable major depression at 3 and 6 months (18% vs. 4%, 10% vs. 0%, respectively.) They also exhibited lower rates of moderate to severe anxiety (17% vs. 4%) at 3 months, compared with those receiving standard care. With as many as one in seven women suffering from postpartum depression, these findings represent a substantial public health benefit.

In summary, insomnia is a critical area of focus for any provider diagnosing and treating psychiatric illness. Attempts to optimize sleep, whether through CBT-I or other psychotherapy approaches, or evidence-based medications dosed for appropriate lengths and at safe doses, should be a part of most, if not all, clinical encounters.

Dr. Reid is a board-certified psychiatrist and award-winning medical educator with a private practice in Philadelphia, as well as a clinical faculty role at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia. She attended medical school at Columbia University, New York, and completed her psychiatry residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Reid is a regular contributor to Psychology Today with her blog, “Think Like a Shrink,” and writes and podcasts as The Reflective Doc.

References

1. Voitsidis P et al. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Jul;289:113076. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. Ford DE and Kamerow DB. JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030.

4. Ohayon MM and Roth T. J Psychiatr Res. Jan-Feb 2003;37(1):9-15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3.

5. Seow LSE et al. J Ment Health. 2016 Dec;25(6):492-9. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1124390.

6. Thase ME. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 17:28-31; discussion 46-8.

7. Baglioni C et al. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1-3):10-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011.

8. Hertenstein E et al. Sleep Med Rev. 2019 Feb;43:96-105. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006.

9. Brower KJ et al. Medical Hypotheses. 2010;74(5):928-33. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.10.020.

10. Laskemoen JF et al. Compr Psychiatry. 2019 May;91:6-12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.02.006.

11. Kay SR et al. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261.

12. Hall R. Psychosomatics. May-Jun 1995;36(3):267-75. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8.

13. Perlis ML et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;77(6):e726-33. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10131.

14. Morin CM et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.610.

15. Cheung J et al. Sleep Med Clin. 2019 Jun;14(2):253-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.006.

16. Bertisch SM et al. Sleep. 2014 Feb 1. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3410.

17. Okajima I et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2010 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00481.x.

18. Trauer JM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Aug 4. doi: 10.7326/M14-2841.

19. Edinger J et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8986.

20. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/for-clinicians.html.

21. National Institutes of Health. Sleep Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/sleep-health.

22. Felder JN et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(5):484-92. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4491.

23. Felder JN et al. Sleep. 2022 Feb 14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab280.

Data suggests this symptom, defined as chronic sleep onset and/or sleep continuity problems associated with impaired daytime functioning, is common in psychiatric illnesses, and can worsen their course.2

The incidence of psychiatric illness in patients with insomnia is estimated at near 50%, with the highest rates found in mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, as well as anxiety disorders.3 In patients with diagnosed major depressive disorder, insomnia rates can approach 90%.4-6

Insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for development of mental illness, including doubling the risk of major depressive disorder and tripling the risk of any depressive or anxiety disorder.7,8 It can also significantly increase the risk of alcohol abuse and psychosis.8

Sleep disturbances can worsen symptoms of diagnosed mental illness, including substance abuse, mood and psychotic disorders.9-10 In one study, nearly 75% of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar spectrum disorder had at least one type of sleep disturbance (insomnia, hypersomnia, or delayed sleep phase).10 This was almost twice the rate in healthy controls. Importantly, compared with well-rested subjects with mental illness in this study, sleep-disordered participants had higher rates of negative and depressive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, as well as significantly lower function via the global assessment of functioning.11,12

Additional data suggests simply being awake during the night (00:00-05:59) elevates risk of suicide. The mean incident rate of completed suicide in one study was a striking four times the rate noted during daytime hours (06:00-23:59 ) (P < .001).13

Although insomnia symptoms can resolve after relief from a particular life stressor, as many as half of patients with more severe symptoms develop a chronic course.14 This then leads to an extended use of many types of sedative-hypnotics designed and studied primarily for short-term use.15 In a survey reviewing national use of prescription drugs for insomnia, as many as 20% of individuals use a medication to target insomnia in a given month.16

Fortunately, despite the many challenges posed by COVID-19, particularly for those with psychiatric illness and limited access to care, telehealth has become more readily available. Additionally, digital versions of evidence-based treatments specifically for sleep problems, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), are regularly being developed.

The benefits of CBT-I have been demonstrated repeatedly and it is recommended as the first line treatment for insomnia by the Clinical Guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.17-21 Studies suggest benefits persist long-term, even after completing the therapy sessions, which differ in durability from medication choices.18

One group that may be particularly suited for treatment with CBT-I is women with insomnia during pregnancy or the postpartum period. In these women, options for treatment may be limited by risk of medication during breastfeeding, as well as difficulty traveling to a physician’s or therapist’s office to receive psychotherapy. However, two recent studies evaluated the use of digital CBT-I to treat insomnia during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, respectively.22-23

In both studies,the same group of women with insomnia diagnosed during pregnancy were given six weekly 20-minute sessions of digital CBT-I or standard treatment for insomnia, including medication and psychotherapy per their usual provider.

By study end, the pregnant women receiving the CBT-I intervention not only had significantly improved severity of insomnia, they also experienced improved depression and anxiety symptoms, and a decrease in the use of prescription or over-the-counter sleep aides, compared with the standard treatment group, lowering the fetal exposure to medication during pregnancy.22

In the more recent study, the same group was followed for 6 months post partum.23 Results were again notable, with the women who received CBT-I reporting significantly less insomnia, as well as significantly lower rates of probable major depression at 3 and 6 months (18% vs. 4%, 10% vs. 0%, respectively.) They also exhibited lower rates of moderate to severe anxiety (17% vs. 4%) at 3 months, compared with those receiving standard care. With as many as one in seven women suffering from postpartum depression, these findings represent a substantial public health benefit.

In summary, insomnia is a critical area of focus for any provider diagnosing and treating psychiatric illness. Attempts to optimize sleep, whether through CBT-I or other psychotherapy approaches, or evidence-based medications dosed for appropriate lengths and at safe doses, should be a part of most, if not all, clinical encounters.

Dr. Reid is a board-certified psychiatrist and award-winning medical educator with a private practice in Philadelphia, as well as a clinical faculty role at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia. She attended medical school at Columbia University, New York, and completed her psychiatry residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Reid is a regular contributor to Psychology Today with her blog, “Think Like a Shrink,” and writes and podcasts as The Reflective Doc.

References

1. Voitsidis P et al. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Jul;289:113076. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. Ford DE and Kamerow DB. JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030.

4. Ohayon MM and Roth T. J Psychiatr Res. Jan-Feb 2003;37(1):9-15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3.

5. Seow LSE et al. J Ment Health. 2016 Dec;25(6):492-9. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1124390.

6. Thase ME. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 17:28-31; discussion 46-8.

7. Baglioni C et al. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1-3):10-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011.

8. Hertenstein E et al. Sleep Med Rev. 2019 Feb;43:96-105. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006.

9. Brower KJ et al. Medical Hypotheses. 2010;74(5):928-33. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.10.020.

10. Laskemoen JF et al. Compr Psychiatry. 2019 May;91:6-12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.02.006.

11. Kay SR et al. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261.

12. Hall R. Psychosomatics. May-Jun 1995;36(3):267-75. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8.

13. Perlis ML et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;77(6):e726-33. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10131.

14. Morin CM et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.610.

15. Cheung J et al. Sleep Med Clin. 2019 Jun;14(2):253-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.006.

16. Bertisch SM et al. Sleep. 2014 Feb 1. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3410.

17. Okajima I et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2010 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00481.x.

18. Trauer JM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Aug 4. doi: 10.7326/M14-2841.

19. Edinger J et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8986.

20. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/for-clinicians.html.

21. National Institutes of Health. Sleep Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/sleep-health.

22. Felder JN et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(5):484-92. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4491.

23. Felder JN et al. Sleep. 2022 Feb 14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab280.

Data suggests this symptom, defined as chronic sleep onset and/or sleep continuity problems associated with impaired daytime functioning, is common in psychiatric illnesses, and can worsen their course.2

The incidence of psychiatric illness in patients with insomnia is estimated at near 50%, with the highest rates found in mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, as well as anxiety disorders.3 In patients with diagnosed major depressive disorder, insomnia rates can approach 90%.4-6

Insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for development of mental illness, including doubling the risk of major depressive disorder and tripling the risk of any depressive or anxiety disorder.7,8 It can also significantly increase the risk of alcohol abuse and psychosis.8

Sleep disturbances can worsen symptoms of diagnosed mental illness, including substance abuse, mood and psychotic disorders.9-10 In one study, nearly 75% of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar spectrum disorder had at least one type of sleep disturbance (insomnia, hypersomnia, or delayed sleep phase).10 This was almost twice the rate in healthy controls. Importantly, compared with well-rested subjects with mental illness in this study, sleep-disordered participants had higher rates of negative and depressive symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, as well as significantly lower function via the global assessment of functioning.11,12

Additional data suggests simply being awake during the night (00:00-05:59) elevates risk of suicide. The mean incident rate of completed suicide in one study was a striking four times the rate noted during daytime hours (06:00-23:59 ) (P < .001).13

Although insomnia symptoms can resolve after relief from a particular life stressor, as many as half of patients with more severe symptoms develop a chronic course.14 This then leads to an extended use of many types of sedative-hypnotics designed and studied primarily for short-term use.15 In a survey reviewing national use of prescription drugs for insomnia, as many as 20% of individuals use a medication to target insomnia in a given month.16

Fortunately, despite the many challenges posed by COVID-19, particularly for those with psychiatric illness and limited access to care, telehealth has become more readily available. Additionally, digital versions of evidence-based treatments specifically for sleep problems, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), are regularly being developed.

The benefits of CBT-I have been demonstrated repeatedly and it is recommended as the first line treatment for insomnia by the Clinical Guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.17-21 Studies suggest benefits persist long-term, even after completing the therapy sessions, which differ in durability from medication choices.18

One group that may be particularly suited for treatment with CBT-I is women with insomnia during pregnancy or the postpartum period. In these women, options for treatment may be limited by risk of medication during breastfeeding, as well as difficulty traveling to a physician’s or therapist’s office to receive psychotherapy. However, two recent studies evaluated the use of digital CBT-I to treat insomnia during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, respectively.22-23

In both studies,the same group of women with insomnia diagnosed during pregnancy were given six weekly 20-minute sessions of digital CBT-I or standard treatment for insomnia, including medication and psychotherapy per their usual provider.

By study end, the pregnant women receiving the CBT-I intervention not only had significantly improved severity of insomnia, they also experienced improved depression and anxiety symptoms, and a decrease in the use of prescription or over-the-counter sleep aides, compared with the standard treatment group, lowering the fetal exposure to medication during pregnancy.22

In the more recent study, the same group was followed for 6 months post partum.23 Results were again notable, with the women who received CBT-I reporting significantly less insomnia, as well as significantly lower rates of probable major depression at 3 and 6 months (18% vs. 4%, 10% vs. 0%, respectively.) They also exhibited lower rates of moderate to severe anxiety (17% vs. 4%) at 3 months, compared with those receiving standard care. With as many as one in seven women suffering from postpartum depression, these findings represent a substantial public health benefit.

In summary, insomnia is a critical area of focus for any provider diagnosing and treating psychiatric illness. Attempts to optimize sleep, whether through CBT-I or other psychotherapy approaches, or evidence-based medications dosed for appropriate lengths and at safe doses, should be a part of most, if not all, clinical encounters.

Dr. Reid is a board-certified psychiatrist and award-winning medical educator with a private practice in Philadelphia, as well as a clinical faculty role at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia. She attended medical school at Columbia University, New York, and completed her psychiatry residency at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Reid is a regular contributor to Psychology Today with her blog, “Think Like a Shrink,” and writes and podcasts as The Reflective Doc.

References

1. Voitsidis P et al. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Jul;289:113076. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. Ford DE and Kamerow DB. JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030.

4. Ohayon MM and Roth T. J Psychiatr Res. Jan-Feb 2003;37(1):9-15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3.

5. Seow LSE et al. J Ment Health. 2016 Dec;25(6):492-9. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1124390.

6. Thase ME. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 17:28-31; discussion 46-8.

7. Baglioni C et al. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1-3):10-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011.

8. Hertenstein E et al. Sleep Med Rev. 2019 Feb;43:96-105. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006.

9. Brower KJ et al. Medical Hypotheses. 2010;74(5):928-33. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.10.020.

10. Laskemoen JF et al. Compr Psychiatry. 2019 May;91:6-12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.02.006.

11. Kay SR et al. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261.

12. Hall R. Psychosomatics. May-Jun 1995;36(3):267-75. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8.

13. Perlis ML et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;77(6):e726-33. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10131.

14. Morin CM et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.610.

15. Cheung J et al. Sleep Med Clin. 2019 Jun;14(2):253-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.006.

16. Bertisch SM et al. Sleep. 2014 Feb 1. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3410.

17. Okajima I et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2010 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00481.x.

18. Trauer JM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Aug 4. doi: 10.7326/M14-2841.

19. Edinger J et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8986.

20. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/for-clinicians.html.

21. National Institutes of Health. Sleep Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/sleep-health.

22. Felder JN et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(5):484-92. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4491.

23. Felder JN et al. Sleep. 2022 Feb 14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab280.

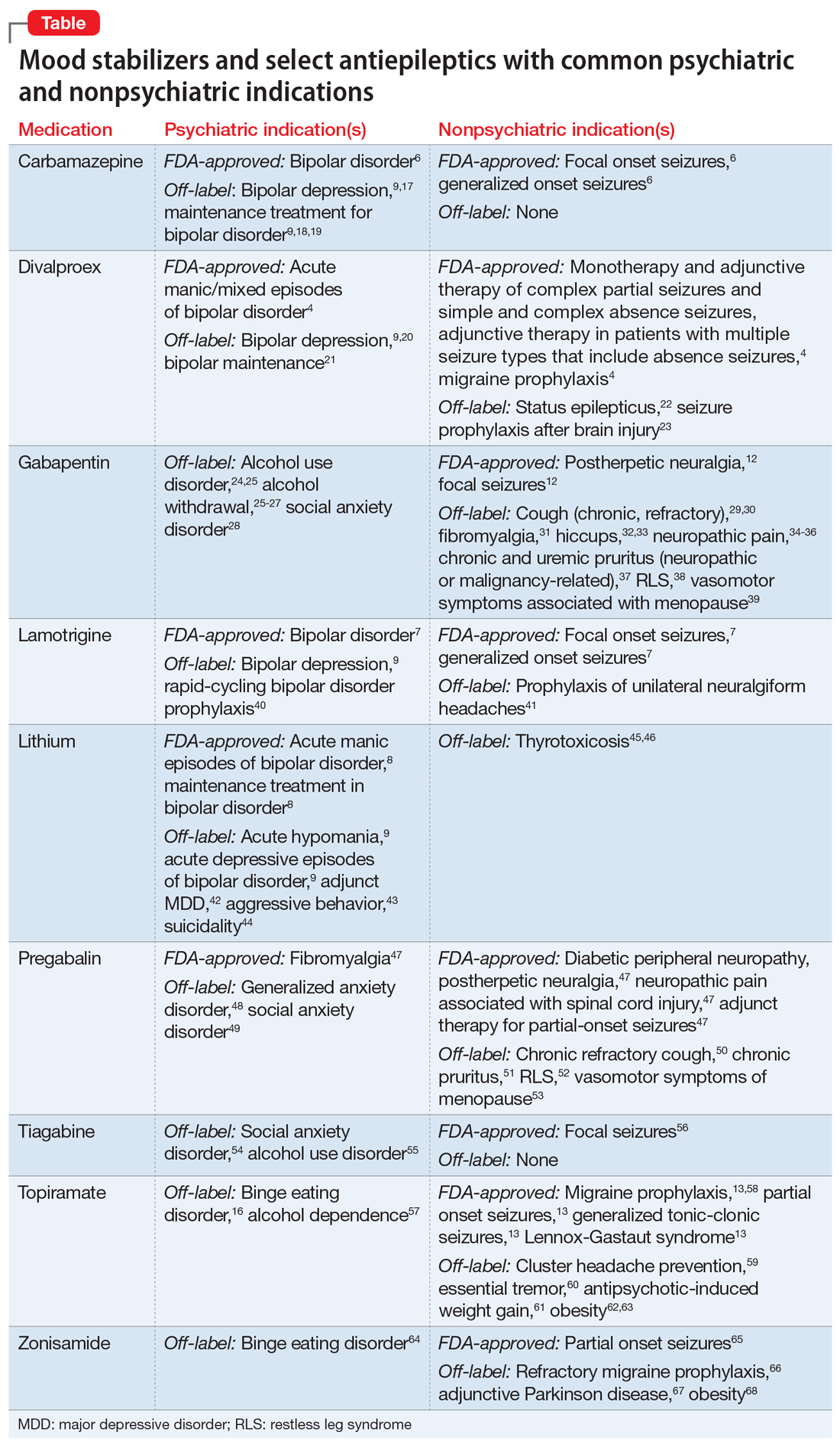

Psychiatric and nonpsychiatric indications for mood stabilizers and select antiepileptics

Mr. B, age 64, is being treated in the psychiatric clinic for generalized anxiety disorder. He also has a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis. His present medications include metformin 500 mg twice daily, escitalopram 20 mg/d, and a multivitamin.

Three months after a shingles outbreak on his left trunk, Mr. B develops a sharp, burning pain and hypersensitivity to light in the same area as the shingles flare-up. He is diagnosed with postherpetic neuralgia. Despite a 12-week trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy, Mr. B continues to report excessive worry, irritability, poor concentration, psychomotor restlessness, and poor sleep.

Contrasting with the serendipitous discovery of iproniazid and chlorpromazine leading to the development of the current spectrum of antidepressant and antipsychotic agents, discovery of the benefits various antiepileptic agents have in bipolar disorder has not led to a similar proliferation of medication development for bipolar mania or depression.1-3 Divalproex, one of the most commonly used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in psychiatry, was thought to be an inactive organic solvent until it was used in 1962 to test the anticonvulsant activity of other compounds. This led to the discovery and subsequent use of divalproex in patients with epilepsy, followed by FDA approval in bipolar disorder.4,5 Off-label use of many AEDs as mood-stabilizing agents in bipolar disorder led to the emergence of carbamazepine, divalproex, and lamotrigine, which joined lithium as classic mood-stabilizing agents.4,6-8 Amid varying definitions of “mood stabilizer,” many AEDs have failed to demonstrate mood-stabilizing effects in bipolar disorder and therefore should not all be considered mood stabilizers.9 Nonetheless, the dual use of a single AED for both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric indications can decrease polypharmacy and increase acceptability of medications in patients who have low insight into their illness.10,11

Because AEDs were originally purposed to treat neurologic disease, psychiatric indications must first be established before considering other indications. AEDs as a class have broad pharmacologic actions, but are generally CNS depressants, decreasing brain signaling through mechanisms such as ion channel antagonism (carbamazepine, gabapentin) or alterations to gamma-aminobutyric acid/glutamate signaling (divalproex, topiramate).4,6,12,13 Compared to antidepressants and antipsychotics, whose primary use for psychiatric conditions is firmly rooted in evidence, rational use of AEDs for psychiatric conditions and symptoms depends on the agent-specific efficacy. Patients with comorbid psychiatric and neurologic disorders are ideal candidates for dually indicated AEDs due to these agents’ class effects rooted in epilepsy. Due to the history of positive psychiatric benefits with AEDs, newer agents may be psychiatrically beneficial but will likely follow the discovery of these benefits in patients for whom epilepsy is the primary diagnosis.

Consider the limitations

Using AEDs to reduce polypharmacy should be done judiciously from a drug-drug interaction perspective, because certain AEDs (eg, carbamazepine, divalproex) can greatly influence the metabolism of other medications, which may defeat the best intentions of the original intervention.4,6

Several other limitations should be considered. This article does not include all AEDs, only those commonly used for psychiatric indications with known nonpsychiatric benefits. Some may worsen psychiatric conditions (such as rage and irritability in the case of levetiracetam), and all AEDs have an FDA warning regarding suicidal behaviors and ideation.14,15 Another important limitation is the potential for differential dosing across indications; tolerability concerns may limit adequate dosing across multiple uses. For example, topiramate’s migraine prophylaxis effect can be achieved at much lower doses than the patient-specific efficacy dosing seen in binge eating disorder, with higher doses increasing the propensity for adverse effects.13,16Dual-use AEDs should be considered wherever possible, but judicious review of evidence is necessary to appropriately adjudicate a specific patient’s risk vs benefit. The Table4,6-9,12,13,16-68 provides information on select AEDs with both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric indications, including both FDA-approved and common off-label uses. These indications are limited to adult use only.

CASE CONTINUED

After reviewing Mr. B’s medical history, the treating medical team decides to cross-taper escitalopram to duloxetine 30 mg twice daily. Though his pain lessens after several weeks, it persists enough to interfere with Mr. B’s daily life. In addition to duloxetine, he is started on pregabalin 50 mg 3 times a day. Mr. B’s pain decreases to a tolerable level, and he reports decreased worrying and restlessness, and improvements in concentration and sleep.

1. Meyer JM. A concise guide to monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(12):14-16,18-23,47,A.

2. Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):495-500.

3. López-Mun

4. Depakote [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc; 2021.

5. Henry TR. The history of valproate in clinical neuroscience. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37 Suppl 2:5-16.

6. Tegretol and Tegretol-XR [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Pharmaceuticals Co.; 2020.

7. Lamictal [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2009.

8. Lithobid [package insert]. Baudette, MN: ANI Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

9. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

10. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anosognosia. Common with mental illness. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Common-with-Mental-Illness/Anosognosia

11. Hales CM, Servais J, Martin CB, et al. Prescription drug use among adults aged 40-79 in the United States and Canada. NCHS Data Brief. 2019(347):1-8.

12. Neurontin [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2017.

13. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

14. Molokwu OA, Ezeala-Adikaibe BA, Onwuekwe IO. Levetiracetam-induced rage and suicidality: two case reports and review of literature. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2015;4:79-81.

15. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Statistical Review and Evaluation. Antiepileptic Drugs and Suicidality. 2008. Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Statistical-Review-and-Evaluation--Antiepileptic-Drugs-and-Suicidality.pdf

16. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(9):1039-1048.

17. Zhang ZJ, Kang WH, Tan QR, et al. Adjunctive herbal medicine with carbamazepine for bipolar disorders: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(3-4):360-369.

18. Kleindienst N, Greil W. Differential efficacy of lithium and carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: results of the MAP study. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42 Suppl 1:2-10.

19. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

20. Davis LL, Bartolucci A, Petty F. Divalproex in the treatment of bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(3):259-266.

21. Gyulai L, Bowden CL, McElroy SL, et al. Maintenance efficacy of divalproex in the prevention of bipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(7):1374-1382.

22. Limdi NA, Shimpi AV, Faught E, et al. Efficacy of rapid IV administration of valproic acid for status epilepticus. Neurology. 2005;64(2):353-355.

23. Temkin NR, Dikmen SS, Anderson GD, et al. Valproate therapy for prevention of posttraumatic seizures: a randomized trial. J Neurosurg. 1999; 91(4):593-600.

24. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(1):86-90.

25. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, US Dept of Defense, The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. US Dept of Veterans Affairs/Dept of Defense; 2015. Accessed March 3, 2022. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf

26. Myrick H, Malcolm R, Randall PK, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

27. Ahmed S, Stanciu CN, Kotapati PV, et al. Effectiveness of gabapentin in reducing cravings and withdrawal in alcohol use disorder: a meta-analytic review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019;21(4):19r02465.

28. Pande AC, Davidson JR, Jefferson JW, et al. Treatment of social phobia with gabapentin: a placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(4):341-348.

29. Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1583-1589.

30. Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(1):27-44.

31. Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1336-1344.

32. Alonso-Navarro H, Rubio L, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ. Refractory hiccup: successful treatment with gabapentin. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30(3):186-187.

33. Jatzko A, Stegmeier-Petroianu A, Petroianu GA. Alpha-2-delta ligands for singultus (hiccup) treatment: three case reports. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):756-760.

34. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162-173.

35. Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, et al. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(4):CD007938.

36. Yuan M, Zhou HY, Xiao ZL, et al. Efficacy and safety of gabapentin vs. carbamazepine in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: a meta-analysis. Pain Pract. 2016;16(8):1083-1091.

37. Weisshaar E, Szepietowski JC, Darsow U, et al. European guideline on chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(5):563-581.

38. Garcia-Borreguero D, Silber MH, Winkelman JW, et al. Guidelines for the first-line treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease, prevention and treatment of dopaminergic augmentation: a combined task force of the IRLSSG, EURLSSG, and the RLS-Foundation. Sleep Med. 2016;21:1-11.

39. Cobin RH, Goodman NF; AACE Reproductive Endocrinology Scientific Committee. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology position statement on menopause—2017 update [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2017;23 (12):1488]. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(7):869-880.

40. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Lamictal 614 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;60(11):841-850.

41. May A, Leone M, Afra J, et al. EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(10):1066-1077.

42. Stein G, Bernadt M. Lithium augmentation therapy in tricyclic-resistant depression. A controlled trial using lithium in low and normal doses. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:634-640.

43. Craft M, Ismail IA, Krishnamurti D, et al. Lithium in the treatment of aggression in mentally handicapped patients: a double-blind trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:685-689.

44. Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, et al. Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1805-1819.

45. Dickstein G, Shechner C, Adawi F, et al. Lithium treatment in amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. Am J Med. 1997;102(5):454-458.

46. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Brogioni S, et al. Comparison of radioiodine with radioiodine plus lithium in the treatment of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(2):499-503.

47. Lyrica [package insert]. New York, NY: Parke-Davis, Division of Pfizer Inc; 2020.

48. Lydiard RB, Rickels K, Herman B, et al. Comparative efficacy of pregabalin and benzodiazepines in treating the psychic and somatic symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(2):229-241.

49. Pande AC, Feltner DE, Jefferson JW, et al. Efficacy of the novel anxiolytic pregabalin in social anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled, multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(2):141-149.

50. Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, et al. Pregabalin and speech pathology combination therapy for refractory chronic cough: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2016;149(3):639-648.

51. Matsuda KM, Sharma D, Schonfeld AR, et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):619-625.e6.

52. Allen R, Chen C, Soaita A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, 6-week, dose-ranging study of pregabalin in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2010;11(6):512-519.

53. Loprinzi CL, Qin R, Balcueva EP, et al. Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of pregabalin for alleviating hot flashes, N07C1 [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1808]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):641-647.

54. Dunlop BW, Papp L, Garlow SJ, et al. Tiagabine for social anxiety disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(4):241-244.

55. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. An open pilot study of tiagabine in alcohol dependence: tolerability and clinical effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(9):1375-1380.

56. Gabitril [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc; 2015.

57. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden C, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9370):1677-1685.

58. Linde M, Mulleners WM, Chronicle EP, et al. Topiramate for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(6):CD010610.

59. Pascual J, Láinez MJ, Dodick D, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of chronic and episodic cluster headache: a review. Headache. 2007;47(1):81-89.

60. Ondo WG, Jankovic J, Connor GS, et al. Topiramate in essential tremor: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;66(5):672-677.

61. Ko YH, Joe SH, Jung IK, et al. Topiramate as an adjuvant treatment with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenic patients experiencing weight gain. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005;28(4):169-175.

62. Wilding J, Van Gaal L, Rissanen A, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy and safety of topiramate in the treatment of obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(11):1399-1410.

63. Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Gadde KM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to assess the efficacy and safety of topiramate controlled release in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(6):1480-1486.

64. McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Guerdjikova AI, et al. Zonisamide in the treatment of binge eating disorder with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1897-1906.

65. Zonegran [package insert]. Teaneck, NJ: Eisai Inc; 2006.

66. Drake ME Jr, Greathouse NI, Renner JB, et al. Open-label zonisamide for refractory migraine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(6):278-280.

67. Matsunaga S, Kishi T, Iwata N. Combination therapy with zonisamide and antiparkinson drugs for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(4):1229-1239.

68. Gadde KM, Kopping MF, Wagner HR 2nd, et al. Zonisamide for weight reduction in obese adults: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1557-1564.