User login

Thiazide-Induced Hyponatremia Presenting as a Fall in an Older Adult

Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.The prevalence of hypertension increases with age, primarily due to age-related changes in arterial physiology.1 For older adults, current guidelines regarding blood pressure (BP) treatment goals vary. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 clinical practice guidelines recommend a systolic BP (SBP) treatment goal of < 130 mm Hg for community-dwelling, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized adults aged ≥ 65 years; whereas the American College of Physicians/American Academy of Family Physicians recommend a goal of < 150 mm Hg for those aged ≥ 60 years without comorbidities and < 140 mm Hg for those with increased cardiovascular risk.1-3 Regardless of the specific threshold, agreement that some degree of BP control even in those with advanced age improves outcomes.2

First-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension includes thiazide diuretics, long-acting calcium channel blockers, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. When choosing between these options, it is recommended to engage in shared decision making and to consider the patient’s comorbidities. Among patients who are likely to require a second agent (eg, if initial BP is > 20/10 mm Hg above goal), it is recommended to begin both drugs at the same time, preferably benazepril plus amlodipine due to the reduction in cardiovascular events reported in the ACCOMPLISH trial.4 If BP remains elevated despite 2 agents at moderate to maximum doses, it is important to investigate for secondary hypertension causes and to explore medication adherence as possible etiologies of treatment failure. Older adults are often at higher risk of adverse drug events due to age-related changes in pharmacodynamics. Despite this, there are no guidelines for choosing between different classes of antihypertensives in this population. We present a case of thiazide-induced hyponatremia in an older adult and review the risks of thiazide use in this population.

Case Presentation

A man aged > 90 years was admitted to the hospital after a syncopal episode. His history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and vitamin D deficiency. At the time, his home medications were amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, ergocalciferol 50,000 IU weekly, and polyethylene glycol 17 g daily as needed. His syncope workup was unremarkable and included negative orthostatic vital signs, normal serial troponins, an electrocardiogram without ischemic changes, normal serum creatinine, sodium, and glucose, and a head computed tomography without any acute abnormality. Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, he had multiple elevated SBP readings, including many > 200 mm Hg. On discharge, in addition to continuing his home medications, he was started on valsartan 20 mg daily and enrolled in a remote BP monitoring program.

Three weeks later, the patient was seen by their primary care practitioner for follow-up. He reported adherence to his antihypertensive regimen. However, his remote BP monitoring revealed persistently elevated BPs, with an average of 179/79 mm Hg, a high of 205/85 mm Hg, and a low of 150/67 mm Hg over the previous 7 days. Laboratory tests obtained at the visit were notable for serum sodium of 138 mmol/L and potassium of 4.1 mmol/L. His weight was 87 kg. Given persistently elevated BP readings, in addition to continuing his amlodipine 5 mg daily and valsartan 20 mg daily, he was started on hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily, with plans to repeat a basic metabolic panel in 2 weeks.

Two weeks later, he fell after getting out of his bed. On examination, he was noted to have dry mucous membranes, and although no formal delirium screening was performed, he was able to repeat the months of the year backward. Vital signs were notable for positive postural hypertension, and his laboratory tests revealed a normal serum creatinine, serum sodium of 117 mmol/L

Discussion

Although thiazide diuretics are recommended as first-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension, they are known to cause electrolyte abnormalities, including hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia.4 These metabolic derangements are more likely to occur in older adults. One study of adults aged ≥ 65 years found that at 9 months of follow-up, 14.3% of new thiazide users had developed a thiazide-related metabolic adverse event (hyponatremia < 135 mmol/L, hypokalemia < 3.5 mmol/L, and decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate by > 25%) compared with 6.0% of nonusers (P < .001; number needed to harm [NNH] = 12).5 In addition, 3.8% of new thiazide users had an emergency department visit or were hospitalized for complications related to thiazides compared with only 2.0% of nonusers (P = .02; NNH = 56).5 Independent risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia include high-comorbidity burden, low body weight, low-normal or unmeasured serum sodium, low potassium, and aged > 70 years.5-7 Each 10-year increment in age is associated with a 2-fold increase in risk, suggesting that older adults are at a much higher risk for hyponatremia than their younger peers.6

Despite their designation as a first-line option for uncomplicated hypertension, thiazide diuretics may cause more harm than good in some older adults, especially those with additional risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia. In this population, these adverse effects should be discussed before starting thiazides for the treatment of hypertension. If thiazides are initiated, they should be started at the lowest possible dose, and plans made to monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation or dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy.

Medication Management in Older Adults

Due to the risks of medication use in older adults, the phrase “start low, go slow” is commonly used in geriatric medicine to describe the optimal method for initiation and up-titration of new medication with the hope of mitigating adverse drug events. In our case, we started valsartan at 20 mg daily—one-fourth the recommended initial dose. Although this strategy is reasonable to “start low,” we were not surprised to find that the patient’s BP did not markedly improve on such a low dose. The team could have increased the valsartan dose to a therapeutically efficacious dose before choosing to add another hypertensive agent. In alignment with geriatric prescribing principles, starting at the lowest possible dose of hydrochlorothiazide is recommended.5 However, the clinician started hydrochlorothiazide at 25 mg daily, potentially increasing this patient’s risk of electrolyte abnormalities and eventual fall.

Managing hypertension also invites a discussion of polypharmacy and medication adherence. Older adults are at risk of polypharmacy, defined as the prescription of 5 or more medications.8 Polypharmacy is associated with increased hospitalizations, higher costs of care for individuals and health care systems, increased risks of adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, and lower quality of life for patients.9 In some situations, the risks of polypharmacy may outweigh the benefits of using multiple antihypertensives with different mechanisms of action if patients can reach their BP goal on the maximum dose of a single agent. For patients taking multiple antihypertensives, it is important to routinely monitor BP and assess whether deprescribing is indicated. Cognitive impairment and decreased social support may affect medication adherence for older adults.6 Clinicians should be aware of strategies, such as medication reminders and pillboxes, to increase antihypertensive medication adherence. Polypills that contain 2 antihypertensives can be another tool used to manage older adults to increase adherence and decrease health care costs.10

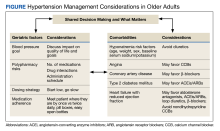

A current strategy that encompasses discussing many, if not all, of these noted elements is the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System. This framework uses evidence-based tools to provide care for older adults across all clinical settings and highlights the 4Ms: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.11 Medication considers whether a medication is necessary, whether its use has benefits that outweigh the risks, and how it interacts with what matters, mentation, and mobility. In particular, what matters plays an important role in hypertension management in older adults given the recommended target BP differs, depending on which specialty organization guideline is followed. By better understanding what matters to patients, including their goals and priorities, clinicians can engage patients in shared decision making and provide individualized recommendations based on geriatric principles (eg, start low, go slow, principles of medication adherence) and patient comorbidities (eg, medical history and risk factors for hyponatremia) to help patients make a more informed choice about their antihypertensive treatment regimen (Figure).

Conclusions

This case illustrates the need for a specialized approach to hypertension management in older adults and the risks of thiazide diuretics in this population. Clinicians should consider BP goals, patient-specific factors, and principles of medication management in older adults. If initiating thiazide therapy, discuss the risks associated with use, start at the lowest possible dose, and monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation/dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy to decrease the risk of adverse events. Finally, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System framework can be a useful when considering the addition of a new medication in an older adult’s treatment plan.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the New England Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, and the Cincinnati VeteransAffairs Medical Center.

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127-e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

2. Davis LL. Hypertension: how low to go when treating older adults. J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(1):1-6. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.10.010

3. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):430-437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785

4. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(20):2037-2114. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.008

5. Makam AN, Boscardin WJ, Miao Y, Steinman MA. Risk of thiazide-induced metabolic adverse events in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1039-1045. doi:10.1111/jgs.12839

6. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Wong TY, Leung CB, Li PK. Risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatraemia. QJM. 2003;96(12):911-917. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg157

7. Clayton JA, Rodgers S, Blakey J, Avery A, Hall IP. Thiazide diuretic prescription and electrolyte abnormalities in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(1):87-95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02531.x

8. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173-186. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.002

9. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1045-1060. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313236

10. Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, Zhang J, Panjabi S. Single-pill vs free-equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta-analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(12):898-909. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00550.x

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.The prevalence of hypertension increases with age, primarily due to age-related changes in arterial physiology.1 For older adults, current guidelines regarding blood pressure (BP) treatment goals vary. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 clinical practice guidelines recommend a systolic BP (SBP) treatment goal of < 130 mm Hg for community-dwelling, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized adults aged ≥ 65 years; whereas the American College of Physicians/American Academy of Family Physicians recommend a goal of < 150 mm Hg for those aged ≥ 60 years without comorbidities and < 140 mm Hg for those with increased cardiovascular risk.1-3 Regardless of the specific threshold, agreement that some degree of BP control even in those with advanced age improves outcomes.2

First-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension includes thiazide diuretics, long-acting calcium channel blockers, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. When choosing between these options, it is recommended to engage in shared decision making and to consider the patient’s comorbidities. Among patients who are likely to require a second agent (eg, if initial BP is > 20/10 mm Hg above goal), it is recommended to begin both drugs at the same time, preferably benazepril plus amlodipine due to the reduction in cardiovascular events reported in the ACCOMPLISH trial.4 If BP remains elevated despite 2 agents at moderate to maximum doses, it is important to investigate for secondary hypertension causes and to explore medication adherence as possible etiologies of treatment failure. Older adults are often at higher risk of adverse drug events due to age-related changes in pharmacodynamics. Despite this, there are no guidelines for choosing between different classes of antihypertensives in this population. We present a case of thiazide-induced hyponatremia in an older adult and review the risks of thiazide use in this population.

Case Presentation

A man aged > 90 years was admitted to the hospital after a syncopal episode. His history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and vitamin D deficiency. At the time, his home medications were amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, ergocalciferol 50,000 IU weekly, and polyethylene glycol 17 g daily as needed. His syncope workup was unremarkable and included negative orthostatic vital signs, normal serial troponins, an electrocardiogram without ischemic changes, normal serum creatinine, sodium, and glucose, and a head computed tomography without any acute abnormality. Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, he had multiple elevated SBP readings, including many > 200 mm Hg. On discharge, in addition to continuing his home medications, he was started on valsartan 20 mg daily and enrolled in a remote BP monitoring program.

Three weeks later, the patient was seen by their primary care practitioner for follow-up. He reported adherence to his antihypertensive regimen. However, his remote BP monitoring revealed persistently elevated BPs, with an average of 179/79 mm Hg, a high of 205/85 mm Hg, and a low of 150/67 mm Hg over the previous 7 days. Laboratory tests obtained at the visit were notable for serum sodium of 138 mmol/L and potassium of 4.1 mmol/L. His weight was 87 kg. Given persistently elevated BP readings, in addition to continuing his amlodipine 5 mg daily and valsartan 20 mg daily, he was started on hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily, with plans to repeat a basic metabolic panel in 2 weeks.

Two weeks later, he fell after getting out of his bed. On examination, he was noted to have dry mucous membranes, and although no formal delirium screening was performed, he was able to repeat the months of the year backward. Vital signs were notable for positive postural hypertension, and his laboratory tests revealed a normal serum creatinine, serum sodium of 117 mmol/L

Discussion

Although thiazide diuretics are recommended as first-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension, they are known to cause electrolyte abnormalities, including hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia.4 These metabolic derangements are more likely to occur in older adults. One study of adults aged ≥ 65 years found that at 9 months of follow-up, 14.3% of new thiazide users had developed a thiazide-related metabolic adverse event (hyponatremia < 135 mmol/L, hypokalemia < 3.5 mmol/L, and decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate by > 25%) compared with 6.0% of nonusers (P < .001; number needed to harm [NNH] = 12).5 In addition, 3.8% of new thiazide users had an emergency department visit or were hospitalized for complications related to thiazides compared with only 2.0% of nonusers (P = .02; NNH = 56).5 Independent risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia include high-comorbidity burden, low body weight, low-normal or unmeasured serum sodium, low potassium, and aged > 70 years.5-7 Each 10-year increment in age is associated with a 2-fold increase in risk, suggesting that older adults are at a much higher risk for hyponatremia than their younger peers.6

Despite their designation as a first-line option for uncomplicated hypertension, thiazide diuretics may cause more harm than good in some older adults, especially those with additional risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia. In this population, these adverse effects should be discussed before starting thiazides for the treatment of hypertension. If thiazides are initiated, they should be started at the lowest possible dose, and plans made to monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation or dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy.

Medication Management in Older Adults

Due to the risks of medication use in older adults, the phrase “start low, go slow” is commonly used in geriatric medicine to describe the optimal method for initiation and up-titration of new medication with the hope of mitigating adverse drug events. In our case, we started valsartan at 20 mg daily—one-fourth the recommended initial dose. Although this strategy is reasonable to “start low,” we were not surprised to find that the patient’s BP did not markedly improve on such a low dose. The team could have increased the valsartan dose to a therapeutically efficacious dose before choosing to add another hypertensive agent. In alignment with geriatric prescribing principles, starting at the lowest possible dose of hydrochlorothiazide is recommended.5 However, the clinician started hydrochlorothiazide at 25 mg daily, potentially increasing this patient’s risk of electrolyte abnormalities and eventual fall.

Managing hypertension also invites a discussion of polypharmacy and medication adherence. Older adults are at risk of polypharmacy, defined as the prescription of 5 or more medications.8 Polypharmacy is associated with increased hospitalizations, higher costs of care for individuals and health care systems, increased risks of adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, and lower quality of life for patients.9 In some situations, the risks of polypharmacy may outweigh the benefits of using multiple antihypertensives with different mechanisms of action if patients can reach their BP goal on the maximum dose of a single agent. For patients taking multiple antihypertensives, it is important to routinely monitor BP and assess whether deprescribing is indicated. Cognitive impairment and decreased social support may affect medication adherence for older adults.6 Clinicians should be aware of strategies, such as medication reminders and pillboxes, to increase antihypertensive medication adherence. Polypills that contain 2 antihypertensives can be another tool used to manage older adults to increase adherence and decrease health care costs.10

A current strategy that encompasses discussing many, if not all, of these noted elements is the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System. This framework uses evidence-based tools to provide care for older adults across all clinical settings and highlights the 4Ms: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.11 Medication considers whether a medication is necessary, whether its use has benefits that outweigh the risks, and how it interacts with what matters, mentation, and mobility. In particular, what matters plays an important role in hypertension management in older adults given the recommended target BP differs, depending on which specialty organization guideline is followed. By better understanding what matters to patients, including their goals and priorities, clinicians can engage patients in shared decision making and provide individualized recommendations based on geriatric principles (eg, start low, go slow, principles of medication adherence) and patient comorbidities (eg, medical history and risk factors for hyponatremia) to help patients make a more informed choice about their antihypertensive treatment regimen (Figure).

Conclusions

This case illustrates the need for a specialized approach to hypertension management in older adults and the risks of thiazide diuretics in this population. Clinicians should consider BP goals, patient-specific factors, and principles of medication management in older adults. If initiating thiazide therapy, discuss the risks associated with use, start at the lowest possible dose, and monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation/dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy to decrease the risk of adverse events. Finally, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System framework can be a useful when considering the addition of a new medication in an older adult’s treatment plan.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the New England Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, and the Cincinnati VeteransAffairs Medical Center.

Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease.The prevalence of hypertension increases with age, primarily due to age-related changes in arterial physiology.1 For older adults, current guidelines regarding blood pressure (BP) treatment goals vary. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 clinical practice guidelines recommend a systolic BP (SBP) treatment goal of < 130 mm Hg for community-dwelling, ambulatory, noninstitutionalized adults aged ≥ 65 years; whereas the American College of Physicians/American Academy of Family Physicians recommend a goal of < 150 mm Hg for those aged ≥ 60 years without comorbidities and < 140 mm Hg for those with increased cardiovascular risk.1-3 Regardless of the specific threshold, agreement that some degree of BP control even in those with advanced age improves outcomes.2

First-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension includes thiazide diuretics, long-acting calcium channel blockers, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. When choosing between these options, it is recommended to engage in shared decision making and to consider the patient’s comorbidities. Among patients who are likely to require a second agent (eg, if initial BP is > 20/10 mm Hg above goal), it is recommended to begin both drugs at the same time, preferably benazepril plus amlodipine due to the reduction in cardiovascular events reported in the ACCOMPLISH trial.4 If BP remains elevated despite 2 agents at moderate to maximum doses, it is important to investigate for secondary hypertension causes and to explore medication adherence as possible etiologies of treatment failure. Older adults are often at higher risk of adverse drug events due to age-related changes in pharmacodynamics. Despite this, there are no guidelines for choosing between different classes of antihypertensives in this population. We present a case of thiazide-induced hyponatremia in an older adult and review the risks of thiazide use in this population.

Case Presentation

A man aged > 90 years was admitted to the hospital after a syncopal episode. His history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and vitamin D deficiency. At the time, his home medications were amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, ergocalciferol 50,000 IU weekly, and polyethylene glycol 17 g daily as needed. His syncope workup was unremarkable and included negative orthostatic vital signs, normal serial troponins, an electrocardiogram without ischemic changes, normal serum creatinine, sodium, and glucose, and a head computed tomography without any acute abnormality. Throughout the patient’s hospital stay, he had multiple elevated SBP readings, including many > 200 mm Hg. On discharge, in addition to continuing his home medications, he was started on valsartan 20 mg daily and enrolled in a remote BP monitoring program.

Three weeks later, the patient was seen by their primary care practitioner for follow-up. He reported adherence to his antihypertensive regimen. However, his remote BP monitoring revealed persistently elevated BPs, with an average of 179/79 mm Hg, a high of 205/85 mm Hg, and a low of 150/67 mm Hg over the previous 7 days. Laboratory tests obtained at the visit were notable for serum sodium of 138 mmol/L and potassium of 4.1 mmol/L. His weight was 87 kg. Given persistently elevated BP readings, in addition to continuing his amlodipine 5 mg daily and valsartan 20 mg daily, he was started on hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily, with plans to repeat a basic metabolic panel in 2 weeks.

Two weeks later, he fell after getting out of his bed. On examination, he was noted to have dry mucous membranes, and although no formal delirium screening was performed, he was able to repeat the months of the year backward. Vital signs were notable for positive postural hypertension, and his laboratory tests revealed a normal serum creatinine, serum sodium of 117 mmol/L

Discussion

Although thiazide diuretics are recommended as first-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension, they are known to cause electrolyte abnormalities, including hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia.4 These metabolic derangements are more likely to occur in older adults. One study of adults aged ≥ 65 years found that at 9 months of follow-up, 14.3% of new thiazide users had developed a thiazide-related metabolic adverse event (hyponatremia < 135 mmol/L, hypokalemia < 3.5 mmol/L, and decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate by > 25%) compared with 6.0% of nonusers (P < .001; number needed to harm [NNH] = 12).5 In addition, 3.8% of new thiazide users had an emergency department visit or were hospitalized for complications related to thiazides compared with only 2.0% of nonusers (P = .02; NNH = 56).5 Independent risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia include high-comorbidity burden, low body weight, low-normal or unmeasured serum sodium, low potassium, and aged > 70 years.5-7 Each 10-year increment in age is associated with a 2-fold increase in risk, suggesting that older adults are at a much higher risk for hyponatremia than their younger peers.6

Despite their designation as a first-line option for uncomplicated hypertension, thiazide diuretics may cause more harm than good in some older adults, especially those with additional risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatremia. In this population, these adverse effects should be discussed before starting thiazides for the treatment of hypertension. If thiazides are initiated, they should be started at the lowest possible dose, and plans made to monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation or dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy.

Medication Management in Older Adults

Due to the risks of medication use in older adults, the phrase “start low, go slow” is commonly used in geriatric medicine to describe the optimal method for initiation and up-titration of new medication with the hope of mitigating adverse drug events. In our case, we started valsartan at 20 mg daily—one-fourth the recommended initial dose. Although this strategy is reasonable to “start low,” we were not surprised to find that the patient’s BP did not markedly improve on such a low dose. The team could have increased the valsartan dose to a therapeutically efficacious dose before choosing to add another hypertensive agent. In alignment with geriatric prescribing principles, starting at the lowest possible dose of hydrochlorothiazide is recommended.5 However, the clinician started hydrochlorothiazide at 25 mg daily, potentially increasing this patient’s risk of electrolyte abnormalities and eventual fall.

Managing hypertension also invites a discussion of polypharmacy and medication adherence. Older adults are at risk of polypharmacy, defined as the prescription of 5 or more medications.8 Polypharmacy is associated with increased hospitalizations, higher costs of care for individuals and health care systems, increased risks of adverse drug events, medication nonadherence, and lower quality of life for patients.9 In some situations, the risks of polypharmacy may outweigh the benefits of using multiple antihypertensives with different mechanisms of action if patients can reach their BP goal on the maximum dose of a single agent. For patients taking multiple antihypertensives, it is important to routinely monitor BP and assess whether deprescribing is indicated. Cognitive impairment and decreased social support may affect medication adherence for older adults.6 Clinicians should be aware of strategies, such as medication reminders and pillboxes, to increase antihypertensive medication adherence. Polypills that contain 2 antihypertensives can be another tool used to manage older adults to increase adherence and decrease health care costs.10

A current strategy that encompasses discussing many, if not all, of these noted elements is the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System. This framework uses evidence-based tools to provide care for older adults across all clinical settings and highlights the 4Ms: what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility.11 Medication considers whether a medication is necessary, whether its use has benefits that outweigh the risks, and how it interacts with what matters, mentation, and mobility. In particular, what matters plays an important role in hypertension management in older adults given the recommended target BP differs, depending on which specialty organization guideline is followed. By better understanding what matters to patients, including their goals and priorities, clinicians can engage patients in shared decision making and provide individualized recommendations based on geriatric principles (eg, start low, go slow, principles of medication adherence) and patient comorbidities (eg, medical history and risk factors for hyponatremia) to help patients make a more informed choice about their antihypertensive treatment regimen (Figure).

Conclusions

This case illustrates the need for a specialized approach to hypertension management in older adults and the risks of thiazide diuretics in this population. Clinicians should consider BP goals, patient-specific factors, and principles of medication management in older adults. If initiating thiazide therapy, discuss the risks associated with use, start at the lowest possible dose, and monitor bloodwork within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation/dose change and periodically thereafter while the patient remains on the therapy to decrease the risk of adverse events. Finally, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health System framework can be a useful when considering the addition of a new medication in an older adult’s treatment plan.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the New England Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, and the Cincinnati VeteransAffairs Medical Center.

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127-e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

2. Davis LL. Hypertension: how low to go when treating older adults. J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(1):1-6. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.10.010

3. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):430-437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785

4. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(20):2037-2114. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.008

5. Makam AN, Boscardin WJ, Miao Y, Steinman MA. Risk of thiazide-induced metabolic adverse events in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1039-1045. doi:10.1111/jgs.12839

6. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Wong TY, Leung CB, Li PK. Risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatraemia. QJM. 2003;96(12):911-917. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg157

7. Clayton JA, Rodgers S, Blakey J, Avery A, Hall IP. Thiazide diuretic prescription and electrolyte abnormalities in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(1):87-95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02531.x

8. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173-186. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.002

9. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1045-1060. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313236

10. Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, Zhang J, Panjabi S. Single-pill vs free-equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta-analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(12):898-909. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00550.x

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127-e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

2. Davis LL. Hypertension: how low to go when treating older adults. J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(1):1-6. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.10.010

3. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):430-437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785

4. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(20):2037-2114. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.008

5. Makam AN, Boscardin WJ, Miao Y, Steinman MA. Risk of thiazide-induced metabolic adverse events in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1039-1045. doi:10.1111/jgs.12839

6. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Wong TY, Leung CB, Li PK. Risk factors for thiazide-induced hyponatraemia. QJM. 2003;96(12):911-917. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg157

7. Clayton JA, Rodgers S, Blakey J, Avery A, Hall IP. Thiazide diuretic prescription and electrolyte abnormalities in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(1):87-95. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02531.x

8. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173-186. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.002

9. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1045-1060. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313236

10. Sherrill B, Halpern M, Khan S, Zhang J, Panjabi S. Single-pill vs free-equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta-analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13(12):898-909. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00550.x

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

Psychotherapy as Effective as Drugs for Depression in HF

TOPLINE:

, a comparative trial of these interventions found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 416 patients with HF and a confirmed depressive disorder from the Cedars-Sinai Health System, with a mean age of 60.71 years, including nearly 42% women and 30% Black individuals, who were randomized to receive one of two evidence-based treatments for depression in HF: Antidepressant medication management (MEDS) or behavioral activation (BA) psychotherapy. BA therapy promotes engaging in pleasurable and rewarding activities without delving into complex cognitive domains explored in cognitive behavioral therapy, another psychotherapy type.

- All patients received 12 weekly sessions delivered via video or telephone, followed by monthly sessions for 3 months, and were then contacted as needed for an additional 6 months.

- The primary outcome was depressive symptom severity at 6 months, measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-Item (PHQ-9), and secondary outcomes included three measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) — caregiver burden, morbidity, and mortality — collected at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Physical and mental HRQOL were measured with the 12-Item Short-Form Medical Outcomes Study (SF-12), HF-specific HRQOL with the 23-item patient-reported Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, caregiver burden with the 26-item Caregiver Burden Questionnaire for HF, morbidity by ED visits, hospital readmissions, and days hospitalized, and mortality data came from medical records and family or caregiver reports, with survival assessed using Kaplan-Meier plots at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Covariates included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, employment, education, insurance type, recruitment site (inpatient or outpatient), ejection fraction (preserved or reduced), New York Heart Association class, medical history, and medications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Depressive symptom severity was reduced at 6 months by nearly 50% for both BA (mean PHQ-9 score, 7.53; P vs baseline < .001) and MEDS (mean PHQ-9 score, 8.09; P vs baseline < .001) participants, with reductions persisting at 12 months and no significant difference between groups.

- Compared with MEDS recipients, those who received BA had slightly higher improvement in physical HRQOL at 6 months (multivariable mean difference without imputation, 2.13; 95% CI, 0.06-4.20; P = .04), but there were no statistically significant differences between groups in mental HRQOL, HF-specific HRQOL, or caregiver burden at 3, 6, or 12 months.

- Patients who received BA were significantly less likely than those in the MEDS group to have ED visits and spent fewer days in hospital at 3, 6, and 12 months, but there was no significant difference in number of hospital readmissions or in mortality at 3, 6, or 12 months.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings of comparable primary effects between BA and MEDS suggest both options are effective and that personal preferences, patient values, and availability of services could inform decisions,” the authors wrote. They noted BA has no pharmacological adverse effects but requires more engagement than drug therapy and might be less accessible.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Waguih William IsHak, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and others. It was published online on January 17, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study had no control group, such as a waiting list, it was impossible to draw conclusions about the natural course of depressive symptoms in HF. However, the authors noted improvements were sustained at 12 months despite substantially diminished contact with intervention teams after 6 months. Researchers were unable to collect data for ED visits, readmissions, and hospital stays outside of California and didn’t assess treatment preference at enrollment, which could have helped inform the association with outcomes and adherence.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute, paid to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. IsHak reported receiving royalties from Springer Nature and Cambridge University Press. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a comparative trial of these interventions found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 416 patients with HF and a confirmed depressive disorder from the Cedars-Sinai Health System, with a mean age of 60.71 years, including nearly 42% women and 30% Black individuals, who were randomized to receive one of two evidence-based treatments for depression in HF: Antidepressant medication management (MEDS) or behavioral activation (BA) psychotherapy. BA therapy promotes engaging in pleasurable and rewarding activities without delving into complex cognitive domains explored in cognitive behavioral therapy, another psychotherapy type.

- All patients received 12 weekly sessions delivered via video or telephone, followed by monthly sessions for 3 months, and were then contacted as needed for an additional 6 months.

- The primary outcome was depressive symptom severity at 6 months, measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-Item (PHQ-9), and secondary outcomes included three measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) — caregiver burden, morbidity, and mortality — collected at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Physical and mental HRQOL were measured with the 12-Item Short-Form Medical Outcomes Study (SF-12), HF-specific HRQOL with the 23-item patient-reported Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, caregiver burden with the 26-item Caregiver Burden Questionnaire for HF, morbidity by ED visits, hospital readmissions, and days hospitalized, and mortality data came from medical records and family or caregiver reports, with survival assessed using Kaplan-Meier plots at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Covariates included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, employment, education, insurance type, recruitment site (inpatient or outpatient), ejection fraction (preserved or reduced), New York Heart Association class, medical history, and medications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Depressive symptom severity was reduced at 6 months by nearly 50% for both BA (mean PHQ-9 score, 7.53; P vs baseline < .001) and MEDS (mean PHQ-9 score, 8.09; P vs baseline < .001) participants, with reductions persisting at 12 months and no significant difference between groups.

- Compared with MEDS recipients, those who received BA had slightly higher improvement in physical HRQOL at 6 months (multivariable mean difference without imputation, 2.13; 95% CI, 0.06-4.20; P = .04), but there were no statistically significant differences between groups in mental HRQOL, HF-specific HRQOL, or caregiver burden at 3, 6, or 12 months.

- Patients who received BA were significantly less likely than those in the MEDS group to have ED visits and spent fewer days in hospital at 3, 6, and 12 months, but there was no significant difference in number of hospital readmissions or in mortality at 3, 6, or 12 months.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings of comparable primary effects between BA and MEDS suggest both options are effective and that personal preferences, patient values, and availability of services could inform decisions,” the authors wrote. They noted BA has no pharmacological adverse effects but requires more engagement than drug therapy and might be less accessible.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Waguih William IsHak, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and others. It was published online on January 17, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study had no control group, such as a waiting list, it was impossible to draw conclusions about the natural course of depressive symptoms in HF. However, the authors noted improvements were sustained at 12 months despite substantially diminished contact with intervention teams after 6 months. Researchers were unable to collect data for ED visits, readmissions, and hospital stays outside of California and didn’t assess treatment preference at enrollment, which could have helped inform the association with outcomes and adherence.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute, paid to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. IsHak reported receiving royalties from Springer Nature and Cambridge University Press. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a comparative trial of these interventions found.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 416 patients with HF and a confirmed depressive disorder from the Cedars-Sinai Health System, with a mean age of 60.71 years, including nearly 42% women and 30% Black individuals, who were randomized to receive one of two evidence-based treatments for depression in HF: Antidepressant medication management (MEDS) or behavioral activation (BA) psychotherapy. BA therapy promotes engaging in pleasurable and rewarding activities without delving into complex cognitive domains explored in cognitive behavioral therapy, another psychotherapy type.

- All patients received 12 weekly sessions delivered via video or telephone, followed by monthly sessions for 3 months, and were then contacted as needed for an additional 6 months.

- The primary outcome was depressive symptom severity at 6 months, measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-Item (PHQ-9), and secondary outcomes included three measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) — caregiver burden, morbidity, and mortality — collected at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Physical and mental HRQOL were measured with the 12-Item Short-Form Medical Outcomes Study (SF-12), HF-specific HRQOL with the 23-item patient-reported Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, caregiver burden with the 26-item Caregiver Burden Questionnaire for HF, morbidity by ED visits, hospital readmissions, and days hospitalized, and mortality data came from medical records and family or caregiver reports, with survival assessed using Kaplan-Meier plots at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- Covariates included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, employment, education, insurance type, recruitment site (inpatient or outpatient), ejection fraction (preserved or reduced), New York Heart Association class, medical history, and medications.

TAKEAWAY:

- Depressive symptom severity was reduced at 6 months by nearly 50% for both BA (mean PHQ-9 score, 7.53; P vs baseline < .001) and MEDS (mean PHQ-9 score, 8.09; P vs baseline < .001) participants, with reductions persisting at 12 months and no significant difference between groups.

- Compared with MEDS recipients, those who received BA had slightly higher improvement in physical HRQOL at 6 months (multivariable mean difference without imputation, 2.13; 95% CI, 0.06-4.20; P = .04), but there were no statistically significant differences between groups in mental HRQOL, HF-specific HRQOL, or caregiver burden at 3, 6, or 12 months.

- Patients who received BA were significantly less likely than those in the MEDS group to have ED visits and spent fewer days in hospital at 3, 6, and 12 months, but there was no significant difference in number of hospital readmissions or in mortality at 3, 6, or 12 months.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings of comparable primary effects between BA and MEDS suggest both options are effective and that personal preferences, patient values, and availability of services could inform decisions,” the authors wrote. They noted BA has no pharmacological adverse effects but requires more engagement than drug therapy and might be less accessible.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Waguih William IsHak, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and others. It was published online on January 17, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study had no control group, such as a waiting list, it was impossible to draw conclusions about the natural course of depressive symptoms in HF. However, the authors noted improvements were sustained at 12 months despite substantially diminished contact with intervention teams after 6 months. Researchers were unable to collect data for ED visits, readmissions, and hospital stays outside of California and didn’t assess treatment preference at enrollment, which could have helped inform the association with outcomes and adherence.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute, paid to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. IsHak reported receiving royalties from Springer Nature and Cambridge University Press. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ibuprofen Fails for Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Colchicine May Benefit Patients With Diabetes and Recent MI

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lp(a) Packs a More Powerful Atherogenic Punch Than LDL

TOPLINE:

While low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles are much more abundant than lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] particles and carry the greatest overall risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), .

METHODOLOGY:

- To compare the atherogenicity of Lp(a) relative to LDL on a per-particle basis, researchers used a genetic analysis because Lp(a) and LDL both contain one apolipoprotein B (apoB) per particle.

- In a genome-wide association study of 502,413 UK Biobank participants, they identified genetic variants uniquely affecting plasma levels of either Lp(a) or LDL particles.

- For these two genetic clusters, they related the change in apoB to the respective change in CHD risk, which allowed them to directly compare the atherogenicity of LDL and Lp(a), particle to particle.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds ratio for CHD for a 50 nmol/L higher Lp(a)-apoB was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.33) compared with 1.04 (95% CI, 1.03-1.05) for the same increment in LDL-apoB.

- Additional supporting evidence was provided by using polygenic scores to rank participants according to the difference in Lp(a)-apoB vs LDL-apoB, which revealed a greater risk for CHD per 50 nmol/L apoB for the Lp(a) cluster (hazard ratio [HR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.36-1.58) than the LDL cluster (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05).

- Based on the data, the researchers estimate that the atherogenicity of Lp(a) is roughly sixfold greater (point estimate of 6.6; 95% CI, 5.1-8.8) than that of LDL on a per-particle basis.

IN PRACTICE:

“There are two clinical implications. First, to completely characterize atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, it is imperative to measure Lp(a) in all adult patients at least once. Second, these studies provide a rationale that targeting Lp(a) with potent and specific drugs may lead to clinically meaningful benefit,” wrote the authors of an accompanying commentary on the study.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Elias Björnson, PhD, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, and an editorial by Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The UK Biobank consists primarily of a Caucasian population, and confirmatory studies in more diverse samples are needed. The working range for the Lp(a) assay used in the study did not cover the full range of Lp(a) values seen in the population. Variations in Lp(a)-apoB and LDL-apoB were estimated from genetic analysis and not measured specifically in biochemical assays.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. Some authors received honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

While low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles are much more abundant than lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] particles and carry the greatest overall risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), .

METHODOLOGY:

- To compare the atherogenicity of Lp(a) relative to LDL on a per-particle basis, researchers used a genetic analysis because Lp(a) and LDL both contain one apolipoprotein B (apoB) per particle.

- In a genome-wide association study of 502,413 UK Biobank participants, they identified genetic variants uniquely affecting plasma levels of either Lp(a) or LDL particles.

- For these two genetic clusters, they related the change in apoB to the respective change in CHD risk, which allowed them to directly compare the atherogenicity of LDL and Lp(a), particle to particle.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds ratio for CHD for a 50 nmol/L higher Lp(a)-apoB was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.33) compared with 1.04 (95% CI, 1.03-1.05) for the same increment in LDL-apoB.

- Additional supporting evidence was provided by using polygenic scores to rank participants according to the difference in Lp(a)-apoB vs LDL-apoB, which revealed a greater risk for CHD per 50 nmol/L apoB for the Lp(a) cluster (hazard ratio [HR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.36-1.58) than the LDL cluster (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05).

- Based on the data, the researchers estimate that the atherogenicity of Lp(a) is roughly sixfold greater (point estimate of 6.6; 95% CI, 5.1-8.8) than that of LDL on a per-particle basis.

IN PRACTICE:

“There are two clinical implications. First, to completely characterize atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, it is imperative to measure Lp(a) in all adult patients at least once. Second, these studies provide a rationale that targeting Lp(a) with potent and specific drugs may lead to clinically meaningful benefit,” wrote the authors of an accompanying commentary on the study.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Elias Björnson, PhD, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, and an editorial by Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The UK Biobank consists primarily of a Caucasian population, and confirmatory studies in more diverse samples are needed. The working range for the Lp(a) assay used in the study did not cover the full range of Lp(a) values seen in the population. Variations in Lp(a)-apoB and LDL-apoB were estimated from genetic analysis and not measured specifically in biochemical assays.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. Some authors received honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

While low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles are much more abundant than lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] particles and carry the greatest overall risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), .

METHODOLOGY:

- To compare the atherogenicity of Lp(a) relative to LDL on a per-particle basis, researchers used a genetic analysis because Lp(a) and LDL both contain one apolipoprotein B (apoB) per particle.

- In a genome-wide association study of 502,413 UK Biobank participants, they identified genetic variants uniquely affecting plasma levels of either Lp(a) or LDL particles.

- For these two genetic clusters, they related the change in apoB to the respective change in CHD risk, which allowed them to directly compare the atherogenicity of LDL and Lp(a), particle to particle.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds ratio for CHD for a 50 nmol/L higher Lp(a)-apoB was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.33) compared with 1.04 (95% CI, 1.03-1.05) for the same increment in LDL-apoB.

- Additional supporting evidence was provided by using polygenic scores to rank participants according to the difference in Lp(a)-apoB vs LDL-apoB, which revealed a greater risk for CHD per 50 nmol/L apoB for the Lp(a) cluster (hazard ratio [HR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.36-1.58) than the LDL cluster (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05).

- Based on the data, the researchers estimate that the atherogenicity of Lp(a) is roughly sixfold greater (point estimate of 6.6; 95% CI, 5.1-8.8) than that of LDL on a per-particle basis.

IN PRACTICE:

“There are two clinical implications. First, to completely characterize atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, it is imperative to measure Lp(a) in all adult patients at least once. Second, these studies provide a rationale that targeting Lp(a) with potent and specific drugs may lead to clinically meaningful benefit,” wrote the authors of an accompanying commentary on the study.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Elias Björnson, PhD, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, and an editorial by Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The UK Biobank consists primarily of a Caucasian population, and confirmatory studies in more diverse samples are needed. The working range for the Lp(a) assay used in the study did not cover the full range of Lp(a) values seen in the population. Variations in Lp(a)-apoB and LDL-apoB were estimated from genetic analysis and not measured specifically in biochemical assays.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. Some authors received honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insulin Resistance Doesn’t Affect Finerenone’s Efficacy

TOPLINE:

In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes, baseline insulin resistance was associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) but not kidney risk and did not affect the efficacy of finerenone.

METHODOLOGY:

- Insulin resistance is implicated in CV disease in patients with CKD, but its role in CKD progression is less clear.

- This post hoc analysis of FIDELITY, a pooled analysis of the and trials, randomly assigned patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (who received optimized renin-angiotensin system blockade) to receive finerenone (10 mg or 20 mg) once daily or placebo and followed them for a median of 3 years.

- An estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR), a measure of insulin resistance, was calculated for 12,964 patients (median age, 65 years), using waist circumference, hypertension status, and glycated hemoglobin.

- Outcomes included a CV composite (time to CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure) and a kidney composite (time to renal failure, a sustained decrease ≥ 57% in the initial estimated glomerular filtration rate, or renal death).

TAKEAWAY:

- The median eGDR was 4.1 mg/kg/min. The 50% of patients with a lower eGDR were considered insulin resistant, whereas the remaining half with a higher eGDR were considered insulin sensitive.

- The incidence rate of CV outcomes was higher among patients with insulin resistance in both the finerenone group (incidence rate per 100 patient-years, 5.18 vs 3.47 among insulin-sensitive patients) and the placebo group (6.34 vs 3.76), but eGDR showed no association with kidney outcomes.

- The efficacy of finerenone vs placebo on CV (Wald test P = .063) and kidney outcomes (Wald test P = .51) did not change significantly across the range of baseline eGDR values.

- The incidences of treatment-emergent adverse events and severe adverse events with finerenone were similar between the insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“The efficacy and safety of finerenone were not modified by baseline insulin resistance. A higher risk of CV — but not kidney outcomes was observed in patients with CKD and T2D with greater insulin resistance,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Thomas Ebert of the Medical Department III — Endocrinology, Nephrology, Rheumatology, University of Leipzig Medical Center, Leipzig, Germany, and published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

This study was not adequately powered to evaluate the statistical significance of the association of eGDR with CV and kidney outcomes and was hypothesis-generating. Further studies are needed to examine whether the effects of insulin resistance differ between individuals with diabetes vs those with advanced CKD with or without diabetes.

DISCLOSURES:

The FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials were conducted and sponsored by Bayer AG. Three authors declared being full-time employees of Bayer. Several authors declared receiving personal fees, consulting fees, grants, or research support from; holding patents with; or having ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies, including Bayer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes, baseline insulin resistance was associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) but not kidney risk and did not affect the efficacy of finerenone.

METHODOLOGY:

- Insulin resistance is implicated in CV disease in patients with CKD, but its role in CKD progression is less clear.

- This post hoc analysis of FIDELITY, a pooled analysis of the and trials, randomly assigned patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (who received optimized renin-angiotensin system blockade) to receive finerenone (10 mg or 20 mg) once daily or placebo and followed them for a median of 3 years.

- An estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR), a measure of insulin resistance, was calculated for 12,964 patients (median age, 65 years), using waist circumference, hypertension status, and glycated hemoglobin.

- Outcomes included a CV composite (time to CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure) and a kidney composite (time to renal failure, a sustained decrease ≥ 57% in the initial estimated glomerular filtration rate, or renal death).

TAKEAWAY:

- The median eGDR was 4.1 mg/kg/min. The 50% of patients with a lower eGDR were considered insulin resistant, whereas the remaining half with a higher eGDR were considered insulin sensitive.