User login

Albuminuria reduction fuels finerenone’s kidney benefits

PHILADELPHIA – Reducing albuminuria is a key mediator of the way finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) reduces adverse renal and cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD), based on findings from two novel mediation analyses run on data from more than 12,000 people included in the two finerenone pivotal trials.

Results from these analyses showed that that finerenone treatment produced in the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD phase 3 trials. FIDELIO-DKD, which had protection against adverse kidney outcomes as its primary endpoint, supplied the data that led to finerenone’s approval in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

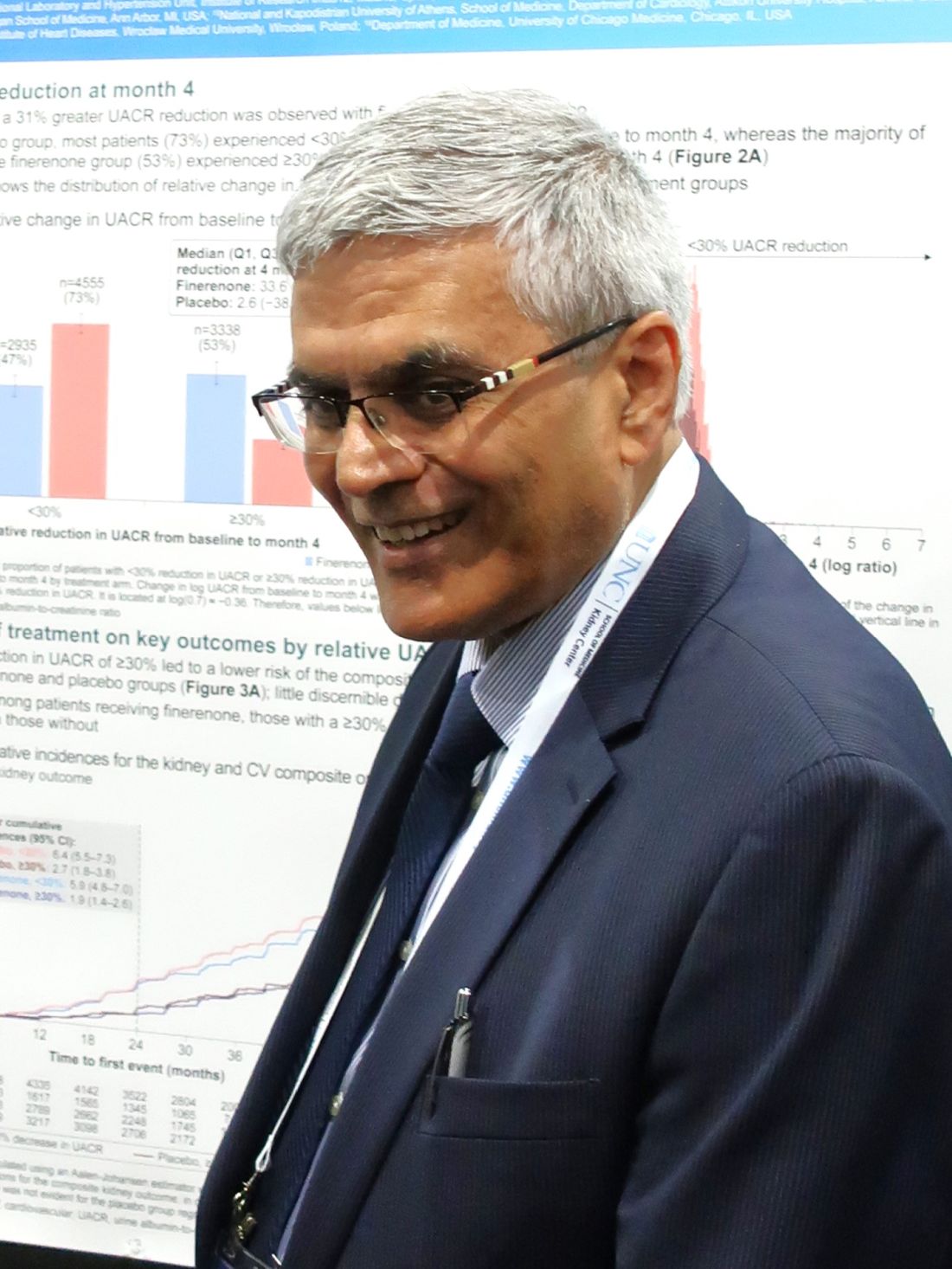

The findings of the mediation analyses underscore the important role that albuminuria plays in the nephropathy and related comorbidities associated with type 2 diabetes and CKD and highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring of albuminuria to guide treatments aimed at minimizing this pathology, said Rajiv Agarwal, MD, who presented a poster on the mediation analyses at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

“My hope is that this [report] heightens awareness of UACR” as an important marker of both CKD and of the response by patients with CKD to their treatment, said Dr. Agarwal, a nephrologist and professor at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

“Only about half of people with type 2 diabetes get their UACR measured even though every guideline says measure UACR in people with diabetes. Our findings say that UACR is important not just for CKD diagnosis but also to give feedback” on whether management is working, Dr. Agarwal said in an interview.

Incorporate UACR into clinical decision-making

“My hope is that clinicians will look at UACR as something they should incorporate into clinical decision-making. I measure UACR in my patients [with CKD and type 2 diabetes] at every visit; it’s so inexpensive. Albuminuria is not a good sign. If it’s not reduced in a patient by at least 30% [the recommended minimum reduction by the American Diabetes Association for people who start with a UACR of at least 300 mg/g] clinicians should think of what else they could do to lower albuminuria”: Reduce salt intake, improve blood pressure control, make sure the patient is adherent to treatments, and add additional treatments, Dr. Agarwal advised.

Multiple efforts are now underway or will soon start to boost the rate at which at-risk people get their UACR measured, noted Leslie A. Inker, MD, in a separate talk during Kidney Week. These efforts include the National Kidney Foundation’s CKD Learning Collaborative, which aims to improve clinician awareness of CKD and improve routine testing for CKD. Early results during 2023 from this program in Missouri showed a nearly 8–percentage point increase in the screening rate for UACR levels in at-risk people, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

A second advance was introduction in 2018 of the “kidney profile” lab order by the American College of Clinical Pathology that allows clinicians to order as a single test both an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and a UACR.

Also, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the National Committee for Quality Assurance have both taken steps to encourage UACR ordering. The NCQA established a new Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set performance measure for U.S. physicians starting in 2023 that will track measurement of UACR and eGFR in people with diabetes. CMS also has made assessment of kidney health a measure of care quality in programs effective in 2023 and 2024, Dr. Inker noted.

Most subjects had elevated UACRs

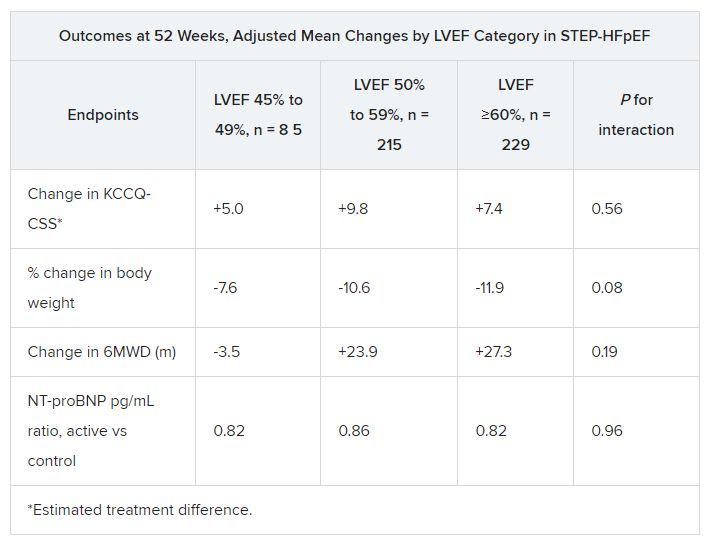

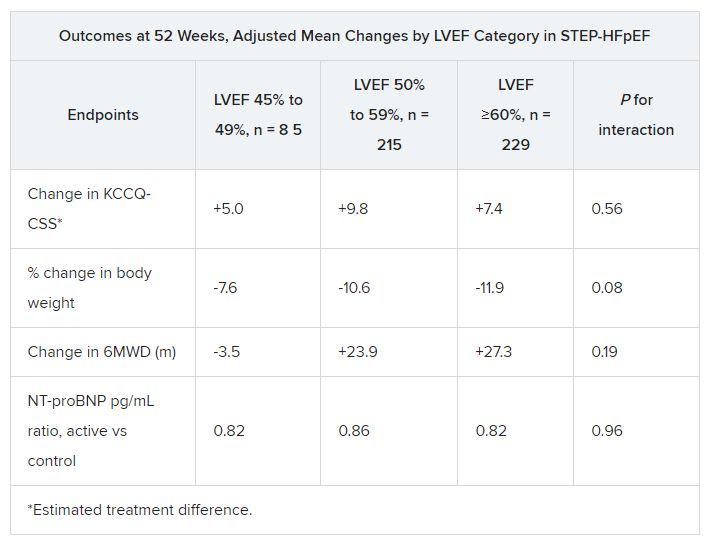

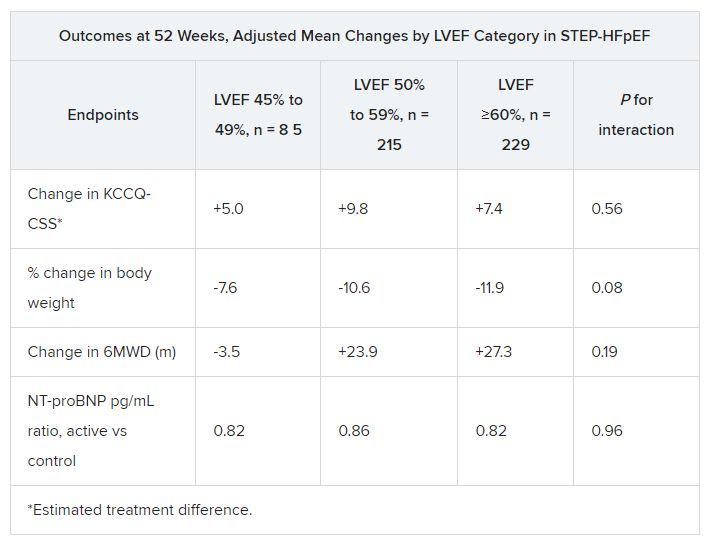

The study run by Dr. Agarwal and his associates used data from 12,512 of the more than 13,000 people enrolled in either FIDELITY-DKD or FIGARO-DKD who had UACR measurements recorded at baseline, at 4 months into either study, or both. Their median UACR at the time they began on finerenone or placebo was 514 mg/g, with 67% having a UACR of at least 300 mg/g (macroalbuminuria) and 31% having a UACR of 30-299 mg/g (microalbuminuria). By design, virtually all patients in these two trials were on a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker), but given the time period when the two trials enrolled participants (during 2015-2018) only 7% of those enrolled were on a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor and only 7% were on a glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist.

Four months after treatment began, 53% of those randomized to finerenone treatment and 27% of those in the placebo arm had their UACR reduced by at least 30% from baseline, the cutpoint chosen by Dr. Agarwal based on the American Diabetes Association guideline.

Kaplan-Meier analyses showed that the incidence of the primary kidney outcome – kidney failure, a sustained ≥ 57% decrease in eGFR from baseline, or kidney death – showed close correlation with at least a 30% reduction in UACR regardless of whether the patients in this subgroup received finerenone or placebo.

A different correlation was found in those with a less than 30% reduction in their UACR from baseline to 4 months, regardless of whether this happened on finerenone or placebo. People in the two finerenone trials who had a lesser reduction from baseline in their UACR also had a significantly higher rate of adverse kidney outcomes whether they received finerenone or placebo.

84% of finerenone’s kidney benefit linked to lowering of UACR

The causal-mediation analysis run by Dr. Agarwal quantified this observation, showing that 84% of finerenone’s effect on the kidney outcome was mediated by the reduction in UACR.

“It seems like the kidney benefit [from finerenone] travels through the level of albuminuria. This has broad implications for treatment of people with type 2 diabetes and CKD,” he said.

The link with reduction in albuminuria was weaker for the primary cardiovascular disease outcome: CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure. The strongest effect on this outcome was only seen in Kaplan-Meier analysis in those on finerenone who had at least a 30% reduction in their UACR. Those on placebo and with a similarly robust 4-month reduction in UACR showed a much more modest cardiovascular benefit that resembled those on either finerenone or placebo who had a smaller, less than 30% UACR reduction. The mediation analysis of these data showed that UACR reduction accounted for about 37% of the observed cardiovascular benefit seen during the trials.

“The effect of UACR is much stronger for the kidney outcomes,” summed up Dr. Agarwal. The results suggest that for cardiovascular outcomes finerenone works through factors other than lowering of UACR, but he admitted that no one currently knows what those other factors might be.

Treat aggressively to lower UACR by 30%

“I wouldn’t stop finerenone treatment in people who do not get a 30% reduction in their UACR” because these analyses suggest that a portion of the overall benefits from finerenone occurs via other mechanisms, he said. But in patients whose UACR is not reduced by at least 30% “be more aggressive on other measures to reduce UACR,” he advised.

The mediation analyses he ran are “the first time this has been done in nephrology,” producing a “groundbreaking” analysis and finding, Dr. Agarwal said. He also highlighted that the findings primarily relate to the importance of controlling UACR rather than an endorsement of finerenone as the best way to achieve this.

“All I care about is that people think about UACR as a modifiable risk factor. It doesn’t have to be treated with finerenone. It could be a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, it could be chlorthalidone [a thiazide diuretic]. It just happened that we had a large dataset of people treated with finerenone or placebo.”

He said that future mediation analyses should look at the link between outcomes and UACR reductions produced by agents from the classes of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists.

FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD were both sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone. Dr. Agarwal has received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer. He has also received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Akebia Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Vifor Pharma, and he is a member of data safety monitoring committees for Chinook and Vertex. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix, and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida.

PHILADELPHIA – Reducing albuminuria is a key mediator of the way finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) reduces adverse renal and cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD), based on findings from two novel mediation analyses run on data from more than 12,000 people included in the two finerenone pivotal trials.

Results from these analyses showed that that finerenone treatment produced in the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD phase 3 trials. FIDELIO-DKD, which had protection against adverse kidney outcomes as its primary endpoint, supplied the data that led to finerenone’s approval in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

The findings of the mediation analyses underscore the important role that albuminuria plays in the nephropathy and related comorbidities associated with type 2 diabetes and CKD and highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring of albuminuria to guide treatments aimed at minimizing this pathology, said Rajiv Agarwal, MD, who presented a poster on the mediation analyses at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

“My hope is that this [report] heightens awareness of UACR” as an important marker of both CKD and of the response by patients with CKD to their treatment, said Dr. Agarwal, a nephrologist and professor at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

“Only about half of people with type 2 diabetes get their UACR measured even though every guideline says measure UACR in people with diabetes. Our findings say that UACR is important not just for CKD diagnosis but also to give feedback” on whether management is working, Dr. Agarwal said in an interview.

Incorporate UACR into clinical decision-making

“My hope is that clinicians will look at UACR as something they should incorporate into clinical decision-making. I measure UACR in my patients [with CKD and type 2 diabetes] at every visit; it’s so inexpensive. Albuminuria is not a good sign. If it’s not reduced in a patient by at least 30% [the recommended minimum reduction by the American Diabetes Association for people who start with a UACR of at least 300 mg/g] clinicians should think of what else they could do to lower albuminuria”: Reduce salt intake, improve blood pressure control, make sure the patient is adherent to treatments, and add additional treatments, Dr. Agarwal advised.

Multiple efforts are now underway or will soon start to boost the rate at which at-risk people get their UACR measured, noted Leslie A. Inker, MD, in a separate talk during Kidney Week. These efforts include the National Kidney Foundation’s CKD Learning Collaborative, which aims to improve clinician awareness of CKD and improve routine testing for CKD. Early results during 2023 from this program in Missouri showed a nearly 8–percentage point increase in the screening rate for UACR levels in at-risk people, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

A second advance was introduction in 2018 of the “kidney profile” lab order by the American College of Clinical Pathology that allows clinicians to order as a single test both an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and a UACR.

Also, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the National Committee for Quality Assurance have both taken steps to encourage UACR ordering. The NCQA established a new Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set performance measure for U.S. physicians starting in 2023 that will track measurement of UACR and eGFR in people with diabetes. CMS also has made assessment of kidney health a measure of care quality in programs effective in 2023 and 2024, Dr. Inker noted.

Most subjects had elevated UACRs

The study run by Dr. Agarwal and his associates used data from 12,512 of the more than 13,000 people enrolled in either FIDELITY-DKD or FIGARO-DKD who had UACR measurements recorded at baseline, at 4 months into either study, or both. Their median UACR at the time they began on finerenone or placebo was 514 mg/g, with 67% having a UACR of at least 300 mg/g (macroalbuminuria) and 31% having a UACR of 30-299 mg/g (microalbuminuria). By design, virtually all patients in these two trials were on a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker), but given the time period when the two trials enrolled participants (during 2015-2018) only 7% of those enrolled were on a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor and only 7% were on a glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist.

Four months after treatment began, 53% of those randomized to finerenone treatment and 27% of those in the placebo arm had their UACR reduced by at least 30% from baseline, the cutpoint chosen by Dr. Agarwal based on the American Diabetes Association guideline.

Kaplan-Meier analyses showed that the incidence of the primary kidney outcome – kidney failure, a sustained ≥ 57% decrease in eGFR from baseline, or kidney death – showed close correlation with at least a 30% reduction in UACR regardless of whether the patients in this subgroup received finerenone or placebo.

A different correlation was found in those with a less than 30% reduction in their UACR from baseline to 4 months, regardless of whether this happened on finerenone or placebo. People in the two finerenone trials who had a lesser reduction from baseline in their UACR also had a significantly higher rate of adverse kidney outcomes whether they received finerenone or placebo.

84% of finerenone’s kidney benefit linked to lowering of UACR

The causal-mediation analysis run by Dr. Agarwal quantified this observation, showing that 84% of finerenone’s effect on the kidney outcome was mediated by the reduction in UACR.

“It seems like the kidney benefit [from finerenone] travels through the level of albuminuria. This has broad implications for treatment of people with type 2 diabetes and CKD,” he said.

The link with reduction in albuminuria was weaker for the primary cardiovascular disease outcome: CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure. The strongest effect on this outcome was only seen in Kaplan-Meier analysis in those on finerenone who had at least a 30% reduction in their UACR. Those on placebo and with a similarly robust 4-month reduction in UACR showed a much more modest cardiovascular benefit that resembled those on either finerenone or placebo who had a smaller, less than 30% UACR reduction. The mediation analysis of these data showed that UACR reduction accounted for about 37% of the observed cardiovascular benefit seen during the trials.

“The effect of UACR is much stronger for the kidney outcomes,” summed up Dr. Agarwal. The results suggest that for cardiovascular outcomes finerenone works through factors other than lowering of UACR, but he admitted that no one currently knows what those other factors might be.

Treat aggressively to lower UACR by 30%

“I wouldn’t stop finerenone treatment in people who do not get a 30% reduction in their UACR” because these analyses suggest that a portion of the overall benefits from finerenone occurs via other mechanisms, he said. But in patients whose UACR is not reduced by at least 30% “be more aggressive on other measures to reduce UACR,” he advised.

The mediation analyses he ran are “the first time this has been done in nephrology,” producing a “groundbreaking” analysis and finding, Dr. Agarwal said. He also highlighted that the findings primarily relate to the importance of controlling UACR rather than an endorsement of finerenone as the best way to achieve this.

“All I care about is that people think about UACR as a modifiable risk factor. It doesn’t have to be treated with finerenone. It could be a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, it could be chlorthalidone [a thiazide diuretic]. It just happened that we had a large dataset of people treated with finerenone or placebo.”

He said that future mediation analyses should look at the link between outcomes and UACR reductions produced by agents from the classes of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists.

FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD were both sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone. Dr. Agarwal has received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer. He has also received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Akebia Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Vifor Pharma, and he is a member of data safety monitoring committees for Chinook and Vertex. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix, and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida.

PHILADELPHIA – Reducing albuminuria is a key mediator of the way finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) reduces adverse renal and cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD), based on findings from two novel mediation analyses run on data from more than 12,000 people included in the two finerenone pivotal trials.

Results from these analyses showed that that finerenone treatment produced in the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD phase 3 trials. FIDELIO-DKD, which had protection against adverse kidney outcomes as its primary endpoint, supplied the data that led to finerenone’s approval in 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD.

The findings of the mediation analyses underscore the important role that albuminuria plays in the nephropathy and related comorbidities associated with type 2 diabetes and CKD and highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring of albuminuria to guide treatments aimed at minimizing this pathology, said Rajiv Agarwal, MD, who presented a poster on the mediation analyses at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

“My hope is that this [report] heightens awareness of UACR” as an important marker of both CKD and of the response by patients with CKD to their treatment, said Dr. Agarwal, a nephrologist and professor at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

“Only about half of people with type 2 diabetes get their UACR measured even though every guideline says measure UACR in people with diabetes. Our findings say that UACR is important not just for CKD diagnosis but also to give feedback” on whether management is working, Dr. Agarwal said in an interview.

Incorporate UACR into clinical decision-making

“My hope is that clinicians will look at UACR as something they should incorporate into clinical decision-making. I measure UACR in my patients [with CKD and type 2 diabetes] at every visit; it’s so inexpensive. Albuminuria is not a good sign. If it’s not reduced in a patient by at least 30% [the recommended minimum reduction by the American Diabetes Association for people who start with a UACR of at least 300 mg/g] clinicians should think of what else they could do to lower albuminuria”: Reduce salt intake, improve blood pressure control, make sure the patient is adherent to treatments, and add additional treatments, Dr. Agarwal advised.

Multiple efforts are now underway or will soon start to boost the rate at which at-risk people get their UACR measured, noted Leslie A. Inker, MD, in a separate talk during Kidney Week. These efforts include the National Kidney Foundation’s CKD Learning Collaborative, which aims to improve clinician awareness of CKD and improve routine testing for CKD. Early results during 2023 from this program in Missouri showed a nearly 8–percentage point increase in the screening rate for UACR levels in at-risk people, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

A second advance was introduction in 2018 of the “kidney profile” lab order by the American College of Clinical Pathology that allows clinicians to order as a single test both an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and a UACR.

Also, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the National Committee for Quality Assurance have both taken steps to encourage UACR ordering. The NCQA established a new Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set performance measure for U.S. physicians starting in 2023 that will track measurement of UACR and eGFR in people with diabetes. CMS also has made assessment of kidney health a measure of care quality in programs effective in 2023 and 2024, Dr. Inker noted.

Most subjects had elevated UACRs

The study run by Dr. Agarwal and his associates used data from 12,512 of the more than 13,000 people enrolled in either FIDELITY-DKD or FIGARO-DKD who had UACR measurements recorded at baseline, at 4 months into either study, or both. Their median UACR at the time they began on finerenone or placebo was 514 mg/g, with 67% having a UACR of at least 300 mg/g (macroalbuminuria) and 31% having a UACR of 30-299 mg/g (microalbuminuria). By design, virtually all patients in these two trials were on a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker), but given the time period when the two trials enrolled participants (during 2015-2018) only 7% of those enrolled were on a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor and only 7% were on a glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist.

Four months after treatment began, 53% of those randomized to finerenone treatment and 27% of those in the placebo arm had their UACR reduced by at least 30% from baseline, the cutpoint chosen by Dr. Agarwal based on the American Diabetes Association guideline.

Kaplan-Meier analyses showed that the incidence of the primary kidney outcome – kidney failure, a sustained ≥ 57% decrease in eGFR from baseline, or kidney death – showed close correlation with at least a 30% reduction in UACR regardless of whether the patients in this subgroup received finerenone or placebo.

A different correlation was found in those with a less than 30% reduction in their UACR from baseline to 4 months, regardless of whether this happened on finerenone or placebo. People in the two finerenone trials who had a lesser reduction from baseline in their UACR also had a significantly higher rate of adverse kidney outcomes whether they received finerenone or placebo.

84% of finerenone’s kidney benefit linked to lowering of UACR

The causal-mediation analysis run by Dr. Agarwal quantified this observation, showing that 84% of finerenone’s effect on the kidney outcome was mediated by the reduction in UACR.

“It seems like the kidney benefit [from finerenone] travels through the level of albuminuria. This has broad implications for treatment of people with type 2 diabetes and CKD,” he said.

The link with reduction in albuminuria was weaker for the primary cardiovascular disease outcome: CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure. The strongest effect on this outcome was only seen in Kaplan-Meier analysis in those on finerenone who had at least a 30% reduction in their UACR. Those on placebo and with a similarly robust 4-month reduction in UACR showed a much more modest cardiovascular benefit that resembled those on either finerenone or placebo who had a smaller, less than 30% UACR reduction. The mediation analysis of these data showed that UACR reduction accounted for about 37% of the observed cardiovascular benefit seen during the trials.

“The effect of UACR is much stronger for the kidney outcomes,” summed up Dr. Agarwal. The results suggest that for cardiovascular outcomes finerenone works through factors other than lowering of UACR, but he admitted that no one currently knows what those other factors might be.

Treat aggressively to lower UACR by 30%

“I wouldn’t stop finerenone treatment in people who do not get a 30% reduction in their UACR” because these analyses suggest that a portion of the overall benefits from finerenone occurs via other mechanisms, he said. But in patients whose UACR is not reduced by at least 30% “be more aggressive on other measures to reduce UACR,” he advised.

The mediation analyses he ran are “the first time this has been done in nephrology,” producing a “groundbreaking” analysis and finding, Dr. Agarwal said. He also highlighted that the findings primarily relate to the importance of controlling UACR rather than an endorsement of finerenone as the best way to achieve this.

“All I care about is that people think about UACR as a modifiable risk factor. It doesn’t have to be treated with finerenone. It could be a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, it could be chlorthalidone [a thiazide diuretic]. It just happened that we had a large dataset of people treated with finerenone or placebo.”

He said that future mediation analyses should look at the link between outcomes and UACR reductions produced by agents from the classes of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists.

FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD were both sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone. Dr. Agarwal has received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer. He has also received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Akebia Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Vifor Pharma, and he is a member of data safety monitoring committees for Chinook and Vertex. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix, and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2023

Dropping aspirin cuts bleeding in LVAD patients: ARIES-HM3

PHILADELPHIA – particularly if it’s a newer device that does not use the centrifugal- or continuous-flow pump technology of conventional LVADs, new randomized results suggest.

“We’ve always thought that somehow aspirin prevents stroke and prevents clotting and that it’s anti-inflammatory, and what we found in ARIES was the exact opposite,” said Mandeep Mehra, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart and Vascular Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, who reported results of the ARIES-HM3 trial of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, a device that uses a fully magnetically levitated rotor to maintain blood flow.

ARIES-HM3 randomly assigned 589 patients who received the HeartMate 3 device to vitamin K therapy with aspirin or to placebo. Dr. Mehra said it was the first international trial to conclusively evaluate medical therapy in patients who get an LVAD.

Unexpected findings

“To be honest with you, we set this up as a safety study to see if we could eliminate aspirin,” Dr. Mehra said in an interview. “We didn’t expect that the bleeding rates would decrease by 34% and that gastrointestinal bleeding in particular would decrease by 40%. We didn’t expect that it would nearly halve the days spent in the hospital, and we didn’t expect that the cost of care would decrease by 40%.”

Dr. Mehra reported the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. They were published simultaneously online in JAMA.

The researchers found that 74% of patients in the placebo group met the primary endpoint of being alive and not having any hemocompatibility events at 12 months vs 68% of the aspirin patients. The rate of nonsurgical bleeding events was 30% in the placebo group versus 42.4% in the aspirin patients. The rates of GI bleeding were 13% and 21.6% in the respective groups.

In his talk, Dr. Mehra noted the placebo group spent 47% fewer days in the hospital for bleeding, with hospitalization costs 41% lower than the aspirin group.

“We are very quick to throw things as deemed medical therapy at patients and this study outcome should give us pause that not everything we do may be right, and that we need to start building a stronger evidence base in medical therapy for what we do with patients that are on device support,” Dr. Mehra said.

Shift of focus to therapy

The study’s focus on aspirin therapy may be as significant as its evaluation of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, discussant Eric David Adler, MD, a cardiologist and section head of heart transplant at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“We focus so much on the device,” he said. “It’s like a set-it-and-forget-it kind of thing and we’re surprised that we see complications because we haven’t put a lot of effort into the medical therapy component.”

But he credited this study for doing just that, adding that it can serve as a model for future studies of LVADs, although such studies can face hurdles. “These studies are not trivial to accomplish,” he said. “Placebo medical therapy studies are very expensive, but I think this is a mandate for doing more studies. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Additionally, evaluating hospital stays in LVAD studies “is a really important endpoint,” Dr. Adler said.

“For me, one of the key things that we don’t think about enough is that lowering days in the hospital is a really big deal,” he said. “No one wants to spend time in the hospital, so anything we can do to lower the amount of hospital days is real impactful.”

Abbott funded and sponsored the ARIES-HM3 trial. Dr. Mehra disclosed relationships with Abbott, Moderna, Natera, Transmedics, Paragonix, NupulseCV, FineHeart, and Leviticus. Dr. Adler has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

PHILADELPHIA – particularly if it’s a newer device that does not use the centrifugal- or continuous-flow pump technology of conventional LVADs, new randomized results suggest.

“We’ve always thought that somehow aspirin prevents stroke and prevents clotting and that it’s anti-inflammatory, and what we found in ARIES was the exact opposite,” said Mandeep Mehra, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart and Vascular Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, who reported results of the ARIES-HM3 trial of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, a device that uses a fully magnetically levitated rotor to maintain blood flow.

ARIES-HM3 randomly assigned 589 patients who received the HeartMate 3 device to vitamin K therapy with aspirin or to placebo. Dr. Mehra said it was the first international trial to conclusively evaluate medical therapy in patients who get an LVAD.

Unexpected findings

“To be honest with you, we set this up as a safety study to see if we could eliminate aspirin,” Dr. Mehra said in an interview. “We didn’t expect that the bleeding rates would decrease by 34% and that gastrointestinal bleeding in particular would decrease by 40%. We didn’t expect that it would nearly halve the days spent in the hospital, and we didn’t expect that the cost of care would decrease by 40%.”

Dr. Mehra reported the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. They were published simultaneously online in JAMA.

The researchers found that 74% of patients in the placebo group met the primary endpoint of being alive and not having any hemocompatibility events at 12 months vs 68% of the aspirin patients. The rate of nonsurgical bleeding events was 30% in the placebo group versus 42.4% in the aspirin patients. The rates of GI bleeding were 13% and 21.6% in the respective groups.

In his talk, Dr. Mehra noted the placebo group spent 47% fewer days in the hospital for bleeding, with hospitalization costs 41% lower than the aspirin group.

“We are very quick to throw things as deemed medical therapy at patients and this study outcome should give us pause that not everything we do may be right, and that we need to start building a stronger evidence base in medical therapy for what we do with patients that are on device support,” Dr. Mehra said.

Shift of focus to therapy

The study’s focus on aspirin therapy may be as significant as its evaluation of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, discussant Eric David Adler, MD, a cardiologist and section head of heart transplant at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“We focus so much on the device,” he said. “It’s like a set-it-and-forget-it kind of thing and we’re surprised that we see complications because we haven’t put a lot of effort into the medical therapy component.”

But he credited this study for doing just that, adding that it can serve as a model for future studies of LVADs, although such studies can face hurdles. “These studies are not trivial to accomplish,” he said. “Placebo medical therapy studies are very expensive, but I think this is a mandate for doing more studies. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Additionally, evaluating hospital stays in LVAD studies “is a really important endpoint,” Dr. Adler said.

“For me, one of the key things that we don’t think about enough is that lowering days in the hospital is a really big deal,” he said. “No one wants to spend time in the hospital, so anything we can do to lower the amount of hospital days is real impactful.”

Abbott funded and sponsored the ARIES-HM3 trial. Dr. Mehra disclosed relationships with Abbott, Moderna, Natera, Transmedics, Paragonix, NupulseCV, FineHeart, and Leviticus. Dr. Adler has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

PHILADELPHIA – particularly if it’s a newer device that does not use the centrifugal- or continuous-flow pump technology of conventional LVADs, new randomized results suggest.

“We’ve always thought that somehow aspirin prevents stroke and prevents clotting and that it’s anti-inflammatory, and what we found in ARIES was the exact opposite,” said Mandeep Mehra, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart and Vascular Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, who reported results of the ARIES-HM3 trial of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, a device that uses a fully magnetically levitated rotor to maintain blood flow.

ARIES-HM3 randomly assigned 589 patients who received the HeartMate 3 device to vitamin K therapy with aspirin or to placebo. Dr. Mehra said it was the first international trial to conclusively evaluate medical therapy in patients who get an LVAD.

Unexpected findings

“To be honest with you, we set this up as a safety study to see if we could eliminate aspirin,” Dr. Mehra said in an interview. “We didn’t expect that the bleeding rates would decrease by 34% and that gastrointestinal bleeding in particular would decrease by 40%. We didn’t expect that it would nearly halve the days spent in the hospital, and we didn’t expect that the cost of care would decrease by 40%.”

Dr. Mehra reported the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. They were published simultaneously online in JAMA.

The researchers found that 74% of patients in the placebo group met the primary endpoint of being alive and not having any hemocompatibility events at 12 months vs 68% of the aspirin patients. The rate of nonsurgical bleeding events was 30% in the placebo group versus 42.4% in the aspirin patients. The rates of GI bleeding were 13% and 21.6% in the respective groups.

In his talk, Dr. Mehra noted the placebo group spent 47% fewer days in the hospital for bleeding, with hospitalization costs 41% lower than the aspirin group.

“We are very quick to throw things as deemed medical therapy at patients and this study outcome should give us pause that not everything we do may be right, and that we need to start building a stronger evidence base in medical therapy for what we do with patients that are on device support,” Dr. Mehra said.

Shift of focus to therapy

The study’s focus on aspirin therapy may be as significant as its evaluation of the HeartMate 3 LVAD, discussant Eric David Adler, MD, a cardiologist and section head of heart transplant at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“We focus so much on the device,” he said. “It’s like a set-it-and-forget-it kind of thing and we’re surprised that we see complications because we haven’t put a lot of effort into the medical therapy component.”

But he credited this study for doing just that, adding that it can serve as a model for future studies of LVADs, although such studies can face hurdles. “These studies are not trivial to accomplish,” he said. “Placebo medical therapy studies are very expensive, but I think this is a mandate for doing more studies. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Additionally, evaluating hospital stays in LVAD studies “is a really important endpoint,” Dr. Adler said.

“For me, one of the key things that we don’t think about enough is that lowering days in the hospital is a really big deal,” he said. “No one wants to spend time in the hospital, so anything we can do to lower the amount of hospital days is real impactful.”

Abbott funded and sponsored the ARIES-HM3 trial. Dr. Mehra disclosed relationships with Abbott, Moderna, Natera, Transmedics, Paragonix, NupulseCV, FineHeart, and Leviticus. Dr. Adler has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AT AHA 2023

Women have worse outcomes in cardiogenic shock

“These data identify the need for us to continue working to identify barriers in terms of diagnosis, management, and technological innovations for women in cardiogenic shock to resolve these issues and improve outcomes,” the senior author of the study, Navin Kapur, MD, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview.

The study is said to be the one of the largest contemporary analyses of real-world registry data on the characteristics and outcomes of women in comparison with men with cardiogenic shock.

It showed sex-specific differences in outcomes that were primarily driven by differences in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock. Women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had more severe cardiogenic shock, worse survival at discharge, and more vascular complications than men. Outcomes in cardiogenic shock related to MI were similar for men and women.

The study, which will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Heart Association, was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Dr. Kapur founded the Cardiogenic Shock Working Group in 2017 to collect quality data on the condition.

“We realized our patients were dying, and we didn’t have enough data on how best to manage them. So, we started this registry, and now have detailed data on close to 9,000 patients with cardiogenic shock from 45 hospitals in the U.S., Mexico, Australia, and Japan,” he explained.

“The primary goal is to try to investigate the questions related to cardiogenic shock that can inform management, and one of the key questions that came up was differences in how men and women present with cardiogenic shock and what their outcomes may be. This is what we are reporting in this paper,” he added.

Cardiogenic shock is defined as having a low cardiac output most commonly because of MI or an episode of acute heart failure, Dr. Kapur said. Patients with cardiogenic shock are identified by their low blood pressure or hypoperfusion evidenced by clinical exam or biomarkers, such as elevated lactate levels.

“In this analysis, we’re looking at patients presenting with cardiogenic shock, so were not looking at the incidence of the condition in men versus women,” Dr. Kapur noted. “However, we believe that cardiogenic shock is probably more underrepresented in women, who may present with an MI or acute heart failure and may or may not be identified as having low cardiac output states until quite late. The likelihood is that the incidence is similar in men and women, but women are more often undiagnosed.”

For the current study, the authors analyzed data on 5,083 patients with cardiogenic shock in the registry, of whom 1,522 (30%) were women. Compared with men, women had slightly higher body mass index (BMI) and smaller body surface area.

Results showed that women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had worse survival at discharge than men (69.9% vs. 74.4%) and a higher rate of refractory shock (SCAI stage E; 26% vs. 21%). Women were also less likely to undergo pulmonary artery catheterization (52.9% vs. 54.6%), heart transplantation (6.5% vs. 10.3%), or left ventricular assist device implantation (7.8% vs. 10%).

Regardless of cardiogenic shock etiology, women had more vascular complications (8.8% vs. 5.7%), bleeding (7.1% vs. 5.2%), and limb ischemia (6.8% vs. 4.5%).

“This analysis is quite revealing. We identified some important distinctions between men and women,” Dr. Kapur commented.

For many patients who present with MI-related cardiogenic shock, many of the baseline characteristics in men and women were quite similar, he said. “But in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock, we saw more differences, with typical comorbidities associated with cardiogenic shock [e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension] being less common in women than in men. This suggests there may be phenotypic differences as to why women present with heart failure shock versus men.”

Dr. Kapur pointed out that differences in BMI or body surface area between men and women may play into some of the management decision-making.

“Women having a smaller stature may lead to a selection bias where we don’t want to use large-bore pumps or devices because we’re worried about causing complications. We found in the analysis that vascular complications such as bleeding or ischemia of the lower extremity where these devices typically go were more frequent in women,” he noted.

“We also found that women were less likely to receive invasive therapies in general, including pulmonary artery catheters, temporary mechanical support, and heart replacements, such as LVAD or transplants,” he added.

Further results showed that, after propensity score matching, some of the gender differences disappeared, but women continued to have a higher rate of vascular complications (10.4% women vs. 7.4% men).

But Dr. Kapur warned that the propensity-matched analysis had some caveats.

“Essentially what we are doing with propensity matching is creating two populations that are as similar as possible, and this reduced the number of patients in the analysis down to 25% of the original population,” he said. “One of the things we had to match was body surface area, and in doing this, we are taking out one of the most important differences between men and women, and as a result, a lot of the differences in outcomes go away.

“In this respect, propensity matching can be a bit of a double-edge sword,” he added. “I think the non–propensity-matched results are more interesting, as they are more of a reflection of the real world.”

Dr. Kapur concluded that these findings are compelling enough to suggest that there are important differences between women and men with cardiogenic shock in terms of outcomes as well as complication rates.

“Our decision-making around women seems to be different to that around men. I think this paper should start to trigger more awareness of that.”

Dr. Kapur also emphasized the importance of paying attention to vascular complications in women.

“The higher rates of bleeding and limb ischemia issues in women may explain the rationale for being less aggressive with invasive therapies in women,” he said. “But we need to come up with better solutions or technologies so they can be used more effectively in women. This could include adapting technology for smaller vascular sizes, which should lead to better outcome and fewer complications in women.”

He added that further granular data on this issue are needed. “We have very limited datasets in cardiogenic shock. There are few randomized controlled trials, and women are not well represented in such trials. We need to make sure we enroll women in randomized trials.”

Dr. Kapur said more women physicians who treat cardiogenic shock are also required, which would include cardiologists, critical care specialists, cardiac surgeons, and anesthesia personnel.

He pointed out that the two first authors of the current study are women – Van-Khue Ton, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Manreet Kanwar, MD, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

“We worked hard to involve women as principal investigators. They led the effort. These are investigations led by women, on women, to advance the care of women,” he commented.

Gender-related inequality

In an editorial accompanying publication of the study, Sara Kalantari, MD, and Jonathan Grinstein, MD, University of Chicago, and Robert O. Roswell, MD, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said these results “provide valuable information about gender-related inequality in care and outcomes in the management of cardiogenic shock, although the exact mechanisms driving these observed differences still need to be elucidated.

“Broadly speaking, barriers in the care of women with heart failure and cardiogenic shock include a reduced awareness among both patients and providers, a deficiency of sex-specific objective criteria for guiding therapy, and unfavorable temporary mechanical circulatory support devices with higher rates of hemocompatibility-related complications in women,” they added.

“In the era of the multidisciplinary shock team and shock pathways with protocolized management algorithms, it is imperative that we still allow for personalization of care to match the physiologic needs of the patient in order for us to continue to close the gender gap in the care of patients presenting with cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“These data identify the need for us to continue working to identify barriers in terms of diagnosis, management, and technological innovations for women in cardiogenic shock to resolve these issues and improve outcomes,” the senior author of the study, Navin Kapur, MD, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview.

The study is said to be the one of the largest contemporary analyses of real-world registry data on the characteristics and outcomes of women in comparison with men with cardiogenic shock.

It showed sex-specific differences in outcomes that were primarily driven by differences in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock. Women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had more severe cardiogenic shock, worse survival at discharge, and more vascular complications than men. Outcomes in cardiogenic shock related to MI were similar for men and women.

The study, which will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Heart Association, was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Dr. Kapur founded the Cardiogenic Shock Working Group in 2017 to collect quality data on the condition.

“We realized our patients were dying, and we didn’t have enough data on how best to manage them. So, we started this registry, and now have detailed data on close to 9,000 patients with cardiogenic shock from 45 hospitals in the U.S., Mexico, Australia, and Japan,” he explained.

“The primary goal is to try to investigate the questions related to cardiogenic shock that can inform management, and one of the key questions that came up was differences in how men and women present with cardiogenic shock and what their outcomes may be. This is what we are reporting in this paper,” he added.

Cardiogenic shock is defined as having a low cardiac output most commonly because of MI or an episode of acute heart failure, Dr. Kapur said. Patients with cardiogenic shock are identified by their low blood pressure or hypoperfusion evidenced by clinical exam or biomarkers, such as elevated lactate levels.

“In this analysis, we’re looking at patients presenting with cardiogenic shock, so were not looking at the incidence of the condition in men versus women,” Dr. Kapur noted. “However, we believe that cardiogenic shock is probably more underrepresented in women, who may present with an MI or acute heart failure and may or may not be identified as having low cardiac output states until quite late. The likelihood is that the incidence is similar in men and women, but women are more often undiagnosed.”

For the current study, the authors analyzed data on 5,083 patients with cardiogenic shock in the registry, of whom 1,522 (30%) were women. Compared with men, women had slightly higher body mass index (BMI) and smaller body surface area.

Results showed that women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had worse survival at discharge than men (69.9% vs. 74.4%) and a higher rate of refractory shock (SCAI stage E; 26% vs. 21%). Women were also less likely to undergo pulmonary artery catheterization (52.9% vs. 54.6%), heart transplantation (6.5% vs. 10.3%), or left ventricular assist device implantation (7.8% vs. 10%).

Regardless of cardiogenic shock etiology, women had more vascular complications (8.8% vs. 5.7%), bleeding (7.1% vs. 5.2%), and limb ischemia (6.8% vs. 4.5%).

“This analysis is quite revealing. We identified some important distinctions between men and women,” Dr. Kapur commented.

For many patients who present with MI-related cardiogenic shock, many of the baseline characteristics in men and women were quite similar, he said. “But in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock, we saw more differences, with typical comorbidities associated with cardiogenic shock [e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension] being less common in women than in men. This suggests there may be phenotypic differences as to why women present with heart failure shock versus men.”

Dr. Kapur pointed out that differences in BMI or body surface area between men and women may play into some of the management decision-making.

“Women having a smaller stature may lead to a selection bias where we don’t want to use large-bore pumps or devices because we’re worried about causing complications. We found in the analysis that vascular complications such as bleeding or ischemia of the lower extremity where these devices typically go were more frequent in women,” he noted.

“We also found that women were less likely to receive invasive therapies in general, including pulmonary artery catheters, temporary mechanical support, and heart replacements, such as LVAD or transplants,” he added.

Further results showed that, after propensity score matching, some of the gender differences disappeared, but women continued to have a higher rate of vascular complications (10.4% women vs. 7.4% men).

But Dr. Kapur warned that the propensity-matched analysis had some caveats.

“Essentially what we are doing with propensity matching is creating two populations that are as similar as possible, and this reduced the number of patients in the analysis down to 25% of the original population,” he said. “One of the things we had to match was body surface area, and in doing this, we are taking out one of the most important differences between men and women, and as a result, a lot of the differences in outcomes go away.

“In this respect, propensity matching can be a bit of a double-edge sword,” he added. “I think the non–propensity-matched results are more interesting, as they are more of a reflection of the real world.”

Dr. Kapur concluded that these findings are compelling enough to suggest that there are important differences between women and men with cardiogenic shock in terms of outcomes as well as complication rates.

“Our decision-making around women seems to be different to that around men. I think this paper should start to trigger more awareness of that.”

Dr. Kapur also emphasized the importance of paying attention to vascular complications in women.

“The higher rates of bleeding and limb ischemia issues in women may explain the rationale for being less aggressive with invasive therapies in women,” he said. “But we need to come up with better solutions or technologies so they can be used more effectively in women. This could include adapting technology for smaller vascular sizes, which should lead to better outcome and fewer complications in women.”

He added that further granular data on this issue are needed. “We have very limited datasets in cardiogenic shock. There are few randomized controlled trials, and women are not well represented in such trials. We need to make sure we enroll women in randomized trials.”

Dr. Kapur said more women physicians who treat cardiogenic shock are also required, which would include cardiologists, critical care specialists, cardiac surgeons, and anesthesia personnel.

He pointed out that the two first authors of the current study are women – Van-Khue Ton, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Manreet Kanwar, MD, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

“We worked hard to involve women as principal investigators. They led the effort. These are investigations led by women, on women, to advance the care of women,” he commented.

Gender-related inequality

In an editorial accompanying publication of the study, Sara Kalantari, MD, and Jonathan Grinstein, MD, University of Chicago, and Robert O. Roswell, MD, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said these results “provide valuable information about gender-related inequality in care and outcomes in the management of cardiogenic shock, although the exact mechanisms driving these observed differences still need to be elucidated.

“Broadly speaking, barriers in the care of women with heart failure and cardiogenic shock include a reduced awareness among both patients and providers, a deficiency of sex-specific objective criteria for guiding therapy, and unfavorable temporary mechanical circulatory support devices with higher rates of hemocompatibility-related complications in women,” they added.

“In the era of the multidisciplinary shock team and shock pathways with protocolized management algorithms, it is imperative that we still allow for personalization of care to match the physiologic needs of the patient in order for us to continue to close the gender gap in the care of patients presenting with cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“These data identify the need for us to continue working to identify barriers in terms of diagnosis, management, and technological innovations for women in cardiogenic shock to resolve these issues and improve outcomes,” the senior author of the study, Navin Kapur, MD, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview.

The study is said to be the one of the largest contemporary analyses of real-world registry data on the characteristics and outcomes of women in comparison with men with cardiogenic shock.

It showed sex-specific differences in outcomes that were primarily driven by differences in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock. Women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had more severe cardiogenic shock, worse survival at discharge, and more vascular complications than men. Outcomes in cardiogenic shock related to MI were similar for men and women.

The study, which will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Heart Association, was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Dr. Kapur founded the Cardiogenic Shock Working Group in 2017 to collect quality data on the condition.

“We realized our patients were dying, and we didn’t have enough data on how best to manage them. So, we started this registry, and now have detailed data on close to 9,000 patients with cardiogenic shock from 45 hospitals in the U.S., Mexico, Australia, and Japan,” he explained.

“The primary goal is to try to investigate the questions related to cardiogenic shock that can inform management, and one of the key questions that came up was differences in how men and women present with cardiogenic shock and what their outcomes may be. This is what we are reporting in this paper,” he added.

Cardiogenic shock is defined as having a low cardiac output most commonly because of MI or an episode of acute heart failure, Dr. Kapur said. Patients with cardiogenic shock are identified by their low blood pressure or hypoperfusion evidenced by clinical exam or biomarkers, such as elevated lactate levels.

“In this analysis, we’re looking at patients presenting with cardiogenic shock, so were not looking at the incidence of the condition in men versus women,” Dr. Kapur noted. “However, we believe that cardiogenic shock is probably more underrepresented in women, who may present with an MI or acute heart failure and may or may not be identified as having low cardiac output states until quite late. The likelihood is that the incidence is similar in men and women, but women are more often undiagnosed.”

For the current study, the authors analyzed data on 5,083 patients with cardiogenic shock in the registry, of whom 1,522 (30%) were women. Compared with men, women had slightly higher body mass index (BMI) and smaller body surface area.

Results showed that women with heart failure–related cardiogenic shock had worse survival at discharge than men (69.9% vs. 74.4%) and a higher rate of refractory shock (SCAI stage E; 26% vs. 21%). Women were also less likely to undergo pulmonary artery catheterization (52.9% vs. 54.6%), heart transplantation (6.5% vs. 10.3%), or left ventricular assist device implantation (7.8% vs. 10%).

Regardless of cardiogenic shock etiology, women had more vascular complications (8.8% vs. 5.7%), bleeding (7.1% vs. 5.2%), and limb ischemia (6.8% vs. 4.5%).

“This analysis is quite revealing. We identified some important distinctions between men and women,” Dr. Kapur commented.

For many patients who present with MI-related cardiogenic shock, many of the baseline characteristics in men and women were quite similar, he said. “But in heart failure–related cardiogenic shock, we saw more differences, with typical comorbidities associated with cardiogenic shock [e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension] being less common in women than in men. This suggests there may be phenotypic differences as to why women present with heart failure shock versus men.”

Dr. Kapur pointed out that differences in BMI or body surface area between men and women may play into some of the management decision-making.

“Women having a smaller stature may lead to a selection bias where we don’t want to use large-bore pumps or devices because we’re worried about causing complications. We found in the analysis that vascular complications such as bleeding or ischemia of the lower extremity where these devices typically go were more frequent in women,” he noted.

“We also found that women were less likely to receive invasive therapies in general, including pulmonary artery catheters, temporary mechanical support, and heart replacements, such as LVAD or transplants,” he added.

Further results showed that, after propensity score matching, some of the gender differences disappeared, but women continued to have a higher rate of vascular complications (10.4% women vs. 7.4% men).

But Dr. Kapur warned that the propensity-matched analysis had some caveats.

“Essentially what we are doing with propensity matching is creating two populations that are as similar as possible, and this reduced the number of patients in the analysis down to 25% of the original population,” he said. “One of the things we had to match was body surface area, and in doing this, we are taking out one of the most important differences between men and women, and as a result, a lot of the differences in outcomes go away.

“In this respect, propensity matching can be a bit of a double-edge sword,” he added. “I think the non–propensity-matched results are more interesting, as they are more of a reflection of the real world.”

Dr. Kapur concluded that these findings are compelling enough to suggest that there are important differences between women and men with cardiogenic shock in terms of outcomes as well as complication rates.

“Our decision-making around women seems to be different to that around men. I think this paper should start to trigger more awareness of that.”

Dr. Kapur also emphasized the importance of paying attention to vascular complications in women.

“The higher rates of bleeding and limb ischemia issues in women may explain the rationale for being less aggressive with invasive therapies in women,” he said. “But we need to come up with better solutions or technologies so they can be used more effectively in women. This could include adapting technology for smaller vascular sizes, which should lead to better outcome and fewer complications in women.”

He added that further granular data on this issue are needed. “We have very limited datasets in cardiogenic shock. There are few randomized controlled trials, and women are not well represented in such trials. We need to make sure we enroll women in randomized trials.”

Dr. Kapur said more women physicians who treat cardiogenic shock are also required, which would include cardiologists, critical care specialists, cardiac surgeons, and anesthesia personnel.

He pointed out that the two first authors of the current study are women – Van-Khue Ton, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Manreet Kanwar, MD, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

“We worked hard to involve women as principal investigators. They led the effort. These are investigations led by women, on women, to advance the care of women,” he commented.

Gender-related inequality

In an editorial accompanying publication of the study, Sara Kalantari, MD, and Jonathan Grinstein, MD, University of Chicago, and Robert O. Roswell, MD, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., said these results “provide valuable information about gender-related inequality in care and outcomes in the management of cardiogenic shock, although the exact mechanisms driving these observed differences still need to be elucidated.

“Broadly speaking, barriers in the care of women with heart failure and cardiogenic shock include a reduced awareness among both patients and providers, a deficiency of sex-specific objective criteria for guiding therapy, and unfavorable temporary mechanical circulatory support devices with higher rates of hemocompatibility-related complications in women,” they added.

“In the era of the multidisciplinary shock team and shock pathways with protocolized management algorithms, it is imperative that we still allow for personalization of care to match the physiologic needs of the patient in order for us to continue to close the gender gap in the care of patients presenting with cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2023

Aprocitentan reduces resistant hypertension in CKD

PHILADELPHIA – (CKD). The results come from a prespecified subgroup analysis of data collected in the drug’s pivotal trial, PRECISION.

The findings provide support for potentially using aprocitentan, if approved for U.S. marketing in 2024, in patients with blood pressure that remains elevated despite treatment with three established antihypertensive drug classes and with stage 3 CKD with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is a key group of patients because “chronic kidney disease is the most common comorbidity in patients with resistant hypertension,” said George Bakris, MD, who presented the subgroup analysis at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

The CKD subgroup analysis showed “good evidence for safety and evidence in stage 3 CKD,” a subgroup of 141 patients among the total 730 enrolled in PRECISION, said Dr. Bakris. Professor and director of the Comprehensive Hypertension Center at the University of Chicago, he acknowledged that while the results also showed a signal for safety and efficacy in the 21 enrolled patients with stage 4 hypertension, 15-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, this number of stage 4 patients was too small to allow definitive conclusions.

Nephrologist Nishigandha Pradhan, MD, who cochaired the session with this report, agreed. “Resistant hypertension is a particularly intractable problem in patients with CKD, and the risk is greatest with stage 4 CKD. If studies could show that aprocitentan is safe in people with stage 4 CKD, that would be a big plus, but we need more data,” commented Dr. Pradhan in an interview.

Incremental blood pressure reductions

The parallel-group, phase 3 PRECISION trial investigated the safety and short-term antihypertensive effect of aprocitentan in patients with resistant hypertension. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was blood pressure reduction from baseline in 730 randomized people with persistent systolic hypertension despite treatment with three established antihypertensive agents including a diuretic. The study ran during June 2018–April 2022 at 191 sites in 22 countries.

The primary outcome after 4 weeks on treatment was a least-square mean reduction in office-measured systolic blood pressure, compared with placebo, of 3.8 mm Hg with a 12.5-mg daily oral dose of aprocitentan and 3.7 mm Hg with a 25-mg daily oral dose. Both significant differences were first reported in 2022. Twenty-four–hour ambulatory systolic blood pressures after 4 weeks of treatment fell by an average of 4.2 mm Hg on the lower dose compared with placebo and by an average of 5.9 mm Hg on the higher daily dose, compared with placebo.

Consistent blood pressure reductions occurred in the CKD subgroups. Among people with stage 3 CKD, daytime ambulatory blood pressure at 4 weeks fell by about 10 mm Hg on both the 12.5-mg daily and 25-mg daily doses, compared with placebo.

Among the small number of people with stage 4 CKD, the incremental nighttime systolic blood pressure on aprocitentan, compared with placebo, was even greater, with about a 15–mm Hg incremental reduction on 12.5 mg daily and about a 17–mm Hg incremental reduction on the higher dose.

“This is the first evidence for a change in nocturnal blood pressure in people with stage 4 CKD [and treatment-resistant hypertension], but it was just 21 patients so not yet a big deal,” Dr. Bakris noted.

Increased rates of fluid retention

Although aprocitentan was generally well tolerated, the most common adverse effect was edema or fluid retention, mainly during the first 4 weeks of treatment. In the full PRECISION cohort, this adverse event occurred in 2.1% of people treated with placebo, 9.1% of those on the 12.5-mg daily dose, and in 18.4% of those on the higher dose during the initial 4-week phase of treatment.

Among all stage 3 and 4 CKD patients on aprocitentan, edema or fluid retention occurred in 21% during the first 4 weeks, and in 27% during an additional 32 weeks of treatment with 25 mg aprocitentan daily. A majority of these patients started a diuretic to address their excess fluid, with only two discontinuing aprocitentan treatment.

“Fluid retention is an issue with aprocitentan,” Dr. Bakris acknowledged. But he also highlighted than only 6 of the 162 patients with CKD required hospitalization for heart failure during the study, and one of these cases had placebo treatment. Among the five with acute heart failure while on aprocitentan, none had to stop their treatment, and two had a clear prior history of heart failure.

The companies developing aprocitentan, Janssen and Idorsia, used the PRECISION results as the centerpiece in filing for a new drug approval to the FDA, with a March 2024 goal for the FDA‘s decision. Dr. Bakris called the application “a solid case for approval.” But he added that approval will likely require that all treatment candidates first undergo testing of their heart function or fluid volume, such as a measure of their blood level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, with treatment withheld when the level is too high.

The upside of aprocitentan compared with current drug options for treating resistant hypertension is that it has not appeared to cause any increase in blood potassium levels, which is an issue with the current top agent for resistant hypertension, spironolactone.

“The problem with spironolactone is the risk for hyperkalemia, which keeps us looking for something with lower risk,” commented Dr. Pradhan, a nephrologist with University Hospitals in Cleveland. Hyperkalemia is an even greater risk for people with CKD. Although the PRECISION trial identified the issue of fluid retention with aprocitentan, titrating an effective dose of a loop diuretic for treated patients may effectively blunt the edema risk, Dr. Pradhan said.

Endothelin has a potent vasoconstrictive effect and is “implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension,” Dr. Bakris explained. Aprocitentan antagonizes both the endothelin A and B receptors. The subgroup analyses also showed that in people with CKD, treatment with aprocitentan led to roughly a halving of the baseline level of urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, a small and stable decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate, and a modest and stable increase in blood levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic hormone.

The PRECISION trial was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, the companies jointly developing aprocitentan. Dr. Bakris has been a consultant to Janssen, and also a consultant to or honoraria recipient of Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Dia Medica Therapeutics, Ionis, inREGEN, KBP Biosciences, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Quantum Genomics. Dr. Pradhan had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – (CKD). The results come from a prespecified subgroup analysis of data collected in the drug’s pivotal trial, PRECISION.

The findings provide support for potentially using aprocitentan, if approved for U.S. marketing in 2024, in patients with blood pressure that remains elevated despite treatment with three established antihypertensive drug classes and with stage 3 CKD with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is a key group of patients because “chronic kidney disease is the most common comorbidity in patients with resistant hypertension,” said George Bakris, MD, who presented the subgroup analysis at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

The CKD subgroup analysis showed “good evidence for safety and evidence in stage 3 CKD,” a subgroup of 141 patients among the total 730 enrolled in PRECISION, said Dr. Bakris. Professor and director of the Comprehensive Hypertension Center at the University of Chicago, he acknowledged that while the results also showed a signal for safety and efficacy in the 21 enrolled patients with stage 4 hypertension, 15-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, this number of stage 4 patients was too small to allow definitive conclusions.

Nephrologist Nishigandha Pradhan, MD, who cochaired the session with this report, agreed. “Resistant hypertension is a particularly intractable problem in patients with CKD, and the risk is greatest with stage 4 CKD. If studies could show that aprocitentan is safe in people with stage 4 CKD, that would be a big plus, but we need more data,” commented Dr. Pradhan in an interview.

Incremental blood pressure reductions

The parallel-group, phase 3 PRECISION trial investigated the safety and short-term antihypertensive effect of aprocitentan in patients with resistant hypertension. The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was blood pressure reduction from baseline in 730 randomized people with persistent systolic hypertension despite treatment with three established antihypertensive agents including a diuretic. The study ran during June 2018–April 2022 at 191 sites in 22 countries.

The primary outcome after 4 weeks on treatment was a least-square mean reduction in office-measured systolic blood pressure, compared with placebo, of 3.8 mm Hg with a 12.5-mg daily oral dose of aprocitentan and 3.7 mm Hg with a 25-mg daily oral dose. Both significant differences were first reported in 2022. Twenty-four–hour ambulatory systolic blood pressures after 4 weeks of treatment fell by an average of 4.2 mm Hg on the lower dose compared with placebo and by an average of 5.9 mm Hg on the higher daily dose, compared with placebo.

Consistent blood pressure reductions occurred in the CKD subgroups. Among people with stage 3 CKD, daytime ambulatory blood pressure at 4 weeks fell by about 10 mm Hg on both the 12.5-mg daily and 25-mg daily doses, compared with placebo.

Among the small number of people with stage 4 CKD, the incremental nighttime systolic blood pressure on aprocitentan, compared with placebo, was even greater, with about a 15–mm Hg incremental reduction on 12.5 mg daily and about a 17–mm Hg incremental reduction on the higher dose.

“This is the first evidence for a change in nocturnal blood pressure in people with stage 4 CKD [and treatment-resistant hypertension], but it was just 21 patients so not yet a big deal,” Dr. Bakris noted.

Increased rates of fluid retention

Although aprocitentan was generally well tolerated, the most common adverse effect was edema or fluid retention, mainly during the first 4 weeks of treatment. In the full PRECISION cohort, this adverse event occurred in 2.1% of people treated with placebo, 9.1% of those on the 12.5-mg daily dose, and in 18.4% of those on the higher dose during the initial 4-week phase of treatment.

Among all stage 3 and 4 CKD patients on aprocitentan, edema or fluid retention occurred in 21% during the first 4 weeks, and in 27% during an additional 32 weeks of treatment with 25 mg aprocitentan daily. A majority of these patients started a diuretic to address their excess fluid, with only two discontinuing aprocitentan treatment.

“Fluid retention is an issue with aprocitentan,” Dr. Bakris acknowledged. But he also highlighted than only 6 of the 162 patients with CKD required hospitalization for heart failure during the study, and one of these cases had placebo treatment. Among the five with acute heart failure while on aprocitentan, none had to stop their treatment, and two had a clear prior history of heart failure.

The companies developing aprocitentan, Janssen and Idorsia, used the PRECISION results as the centerpiece in filing for a new drug approval to the FDA, with a March 2024 goal for the FDA‘s decision. Dr. Bakris called the application “a solid case for approval.” But he added that approval will likely require that all treatment candidates first undergo testing of their heart function or fluid volume, such as a measure of their blood level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, with treatment withheld when the level is too high.

The upside of aprocitentan compared with current drug options for treating resistant hypertension is that it has not appeared to cause any increase in blood potassium levels, which is an issue with the current top agent for resistant hypertension, spironolactone.

“The problem with spironolactone is the risk for hyperkalemia, which keeps us looking for something with lower risk,” commented Dr. Pradhan, a nephrologist with University Hospitals in Cleveland. Hyperkalemia is an even greater risk for people with CKD. Although the PRECISION trial identified the issue of fluid retention with aprocitentan, titrating an effective dose of a loop diuretic for treated patients may effectively blunt the edema risk, Dr. Pradhan said.

Endothelin has a potent vasoconstrictive effect and is “implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension,” Dr. Bakris explained. Aprocitentan antagonizes both the endothelin A and B receptors. The subgroup analyses also showed that in people with CKD, treatment with aprocitentan led to roughly a halving of the baseline level of urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, a small and stable decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate, and a modest and stable increase in blood levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic hormone.

The PRECISION trial was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, the companies jointly developing aprocitentan. Dr. Bakris has been a consultant to Janssen, and also a consultant to or honoraria recipient of Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Dia Medica Therapeutics, Ionis, inREGEN, KBP Biosciences, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Quantum Genomics. Dr. Pradhan had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – (CKD). The results come from a prespecified subgroup analysis of data collected in the drug’s pivotal trial, PRECISION.

The findings provide support for potentially using aprocitentan, if approved for U.S. marketing in 2024, in patients with blood pressure that remains elevated despite treatment with three established antihypertensive drug classes and with stage 3 CKD with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is a key group of patients because “chronic kidney disease is the most common comorbidity in patients with resistant hypertension,” said George Bakris, MD, who presented the subgroup analysis at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

The CKD subgroup analysis showed “good evidence for safety and evidence in stage 3 CKD,” a subgroup of 141 patients among the total 730 enrolled in PRECISION, said Dr. Bakris. Professor and director of the Comprehensive Hypertension Center at the University of Chicago, he acknowledged that while the results also showed a signal for safety and efficacy in the 21 enrolled patients with stage 4 hypertension, 15-29 mL/min per 1.73m2, this number of stage 4 patients was too small to allow definitive conclusions.

Nephrologist Nishigandha Pradhan, MD, who cochaired the session with this report, agreed. “Resistant hypertension is a particularly intractable problem in patients with CKD, and the risk is greatest with stage 4 CKD. If studies could show that aprocitentan is safe in people with stage 4 CKD, that would be a big plus, but we need more data,” commented Dr. Pradhan in an interview.

Incremental blood pressure reductions