User login

Trials say start sacubitril-valsartan in hospital in HF with ‘below normal’ LVEF

CLEVELAND – suggests a combined analysis of two major studies.

Short-term risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or HF hospitalization fell 30% for such patients put on the angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) at that early stage, compared with those assigned to receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Of note, the risk-reduction benefit reached 41% among the overwhelming majority of patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% or lower across the two trials, PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF. No such significant benefit was seen in patients with higher LVEF.

The prespecified analysis of 1,347 patients medically stabilized after a “worsening-HF event” was reported by Robert J. Mentz, MD, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

Across both studies, levels of the prognostically telling biomarker NT-proBNP dropped further in the ARNI group, by almost a fourth, compared with those getting an ACE inhibitor or ARB. The difference emerged within a week and was “similar and consistent” throughout at least 8 weeks of follow-up, Dr. Mentz said.

Sacubitril-valsartan is approved in the United States for chronic HF, broadly but with labeling suggesting clearer efficacy at lower LVEF levels, based on the PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF trials.

The PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF trials lending patients to the current analysis demonstrated superiority for the drug vs. an ACE inhibitor or ARB when started in hospital in stabilized patients with HF.

Cautions about starting sacubitril-valsartan

In the pooled analysis, patients on sacubitril-valsartan were more likely to experience symptomatic hypotension, with a relative risk for drug’s known potential side effect reaching 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.72), compared with ACE inhibitor or ARB recipients.

But the hypotension risk when starting the drug is manageable to some extent, observed Dr. Mentz. “We can safely start sacubitril-valsartan in the hospital or early post discharge, but we need to make sure their volume status is okay” and keep track of their blood pressure trajectory, he told this news organization.

Those with initially low BP, unsurprisingly, seem more susceptible to the problem, Dr. Mentz said. In such patients “on antihypertensives or other therapies that aren’t going to give them a clinical outcome benefit,” those meds can be withdrawn or their dosages reduced before sacubitril-valsartan is added.

Such cautions are an “important take-home message” of the analysis, observed invited discussant Carolyn S. P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, after the Dr. Mentz presentation.

Sacubitril-valsartan should be started only in stabilized patients, she emphasized. It should be delayed in those “with ongoing adjustments of antihypertensives, diuretics, and so on,” in whom premature initiation of the drug may promote symptomatic hypotension. Should that happen, Dr. Lam cautioned, there’s a risk that such patients would be “mislabeled as intolerant” of the ARNI and so wouldn’t be started on it later.

The pooled PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF analysis, Dr. Lam proposed, might also help overcome the “clinical inertia and fear” that is slowing the uptake of early guideline-directed drug therapy initiation in patients hospitalized with HF.

LVEF spectrum across two studies

As Dr. Mentz reported, the analysis included 881 and 466 patients from PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, respectively. Of the total, 673 were assigned to receive valsartan and 674 to receive either enalapril or valsartan. Overall, 36% of the population were women.

Patients in PIONEER-HF, with an LVEF 40% or lower, were started on their assigned drug during an acute-HF hospitalization and followed a median of 8 weeks. PARAGLIDE-HF patients, with LVEF higher than 40%, started therapy either in hospital (in 70% of cases) or within 30 days of their HF event; they were followed a median of 6 months.

Hazard ratios for outcomes in the sacubitril-valsartan group vs. those on ACE inhibitors or ARBs were 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.83; P < .0001 for change in NT-proBNP levels. For the composite of CV death or HF hospitalization, HRs were as follows:

- 0.70 (95% CI, 0.54-0.91; P = .0077) overall.

- 0.59 (95% CI, 0.44-0.79) for LVEF < 60%.

- 1.53 (95% CI, 0.80-2.91) for LVEF > 60%.

Current guidelines, Dr. Mentz noted, recommend that sacubitril-valsartan “be initiated de novo” predischarge in patients without contraindications who are hospitalized with acute HF with reduced LVEF. The combined analysis of PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, he said, potentially extends the recommendation “across the ejection fraction spectrum.”

Dr. Mentz has received research support and honoraria from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Fast BioMedical, Gilead, Innolife, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Medable, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Respicardia, Roche, Sanofi, Vifor, Windtree Therapeutics, and Zoll. Dr. Lam has reported financial relationships “with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure,” as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – suggests a combined analysis of two major studies.

Short-term risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or HF hospitalization fell 30% for such patients put on the angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) at that early stage, compared with those assigned to receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Of note, the risk-reduction benefit reached 41% among the overwhelming majority of patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% or lower across the two trials, PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF. No such significant benefit was seen in patients with higher LVEF.

The prespecified analysis of 1,347 patients medically stabilized after a “worsening-HF event” was reported by Robert J. Mentz, MD, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

Across both studies, levels of the prognostically telling biomarker NT-proBNP dropped further in the ARNI group, by almost a fourth, compared with those getting an ACE inhibitor or ARB. The difference emerged within a week and was “similar and consistent” throughout at least 8 weeks of follow-up, Dr. Mentz said.

Sacubitril-valsartan is approved in the United States for chronic HF, broadly but with labeling suggesting clearer efficacy at lower LVEF levels, based on the PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF trials.

The PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF trials lending patients to the current analysis demonstrated superiority for the drug vs. an ACE inhibitor or ARB when started in hospital in stabilized patients with HF.

Cautions about starting sacubitril-valsartan

In the pooled analysis, patients on sacubitril-valsartan were more likely to experience symptomatic hypotension, with a relative risk for drug’s known potential side effect reaching 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.72), compared with ACE inhibitor or ARB recipients.

But the hypotension risk when starting the drug is manageable to some extent, observed Dr. Mentz. “We can safely start sacubitril-valsartan in the hospital or early post discharge, but we need to make sure their volume status is okay” and keep track of their blood pressure trajectory, he told this news organization.

Those with initially low BP, unsurprisingly, seem more susceptible to the problem, Dr. Mentz said. In such patients “on antihypertensives or other therapies that aren’t going to give them a clinical outcome benefit,” those meds can be withdrawn or their dosages reduced before sacubitril-valsartan is added.

Such cautions are an “important take-home message” of the analysis, observed invited discussant Carolyn S. P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, after the Dr. Mentz presentation.

Sacubitril-valsartan should be started only in stabilized patients, she emphasized. It should be delayed in those “with ongoing adjustments of antihypertensives, diuretics, and so on,” in whom premature initiation of the drug may promote symptomatic hypotension. Should that happen, Dr. Lam cautioned, there’s a risk that such patients would be “mislabeled as intolerant” of the ARNI and so wouldn’t be started on it later.

The pooled PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF analysis, Dr. Lam proposed, might also help overcome the “clinical inertia and fear” that is slowing the uptake of early guideline-directed drug therapy initiation in patients hospitalized with HF.

LVEF spectrum across two studies

As Dr. Mentz reported, the analysis included 881 and 466 patients from PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, respectively. Of the total, 673 were assigned to receive valsartan and 674 to receive either enalapril or valsartan. Overall, 36% of the population were women.

Patients in PIONEER-HF, with an LVEF 40% or lower, were started on their assigned drug during an acute-HF hospitalization and followed a median of 8 weeks. PARAGLIDE-HF patients, with LVEF higher than 40%, started therapy either in hospital (in 70% of cases) or within 30 days of their HF event; they were followed a median of 6 months.

Hazard ratios for outcomes in the sacubitril-valsartan group vs. those on ACE inhibitors or ARBs were 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.83; P < .0001 for change in NT-proBNP levels. For the composite of CV death or HF hospitalization, HRs were as follows:

- 0.70 (95% CI, 0.54-0.91; P = .0077) overall.

- 0.59 (95% CI, 0.44-0.79) for LVEF < 60%.

- 1.53 (95% CI, 0.80-2.91) for LVEF > 60%.

Current guidelines, Dr. Mentz noted, recommend that sacubitril-valsartan “be initiated de novo” predischarge in patients without contraindications who are hospitalized with acute HF with reduced LVEF. The combined analysis of PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, he said, potentially extends the recommendation “across the ejection fraction spectrum.”

Dr. Mentz has received research support and honoraria from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Fast BioMedical, Gilead, Innolife, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Medable, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Respicardia, Roche, Sanofi, Vifor, Windtree Therapeutics, and Zoll. Dr. Lam has reported financial relationships “with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure,” as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – suggests a combined analysis of two major studies.

Short-term risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or HF hospitalization fell 30% for such patients put on the angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) at that early stage, compared with those assigned to receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Of note, the risk-reduction benefit reached 41% among the overwhelming majority of patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% or lower across the two trials, PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF. No such significant benefit was seen in patients with higher LVEF.

The prespecified analysis of 1,347 patients medically stabilized after a “worsening-HF event” was reported by Robert J. Mentz, MD, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

Across both studies, levels of the prognostically telling biomarker NT-proBNP dropped further in the ARNI group, by almost a fourth, compared with those getting an ACE inhibitor or ARB. The difference emerged within a week and was “similar and consistent” throughout at least 8 weeks of follow-up, Dr. Mentz said.

Sacubitril-valsartan is approved in the United States for chronic HF, broadly but with labeling suggesting clearer efficacy at lower LVEF levels, based on the PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF trials.

The PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF trials lending patients to the current analysis demonstrated superiority for the drug vs. an ACE inhibitor or ARB when started in hospital in stabilized patients with HF.

Cautions about starting sacubitril-valsartan

In the pooled analysis, patients on sacubitril-valsartan were more likely to experience symptomatic hypotension, with a relative risk for drug’s known potential side effect reaching 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.72), compared with ACE inhibitor or ARB recipients.

But the hypotension risk when starting the drug is manageable to some extent, observed Dr. Mentz. “We can safely start sacubitril-valsartan in the hospital or early post discharge, but we need to make sure their volume status is okay” and keep track of their blood pressure trajectory, he told this news organization.

Those with initially low BP, unsurprisingly, seem more susceptible to the problem, Dr. Mentz said. In such patients “on antihypertensives or other therapies that aren’t going to give them a clinical outcome benefit,” those meds can be withdrawn or their dosages reduced before sacubitril-valsartan is added.

Such cautions are an “important take-home message” of the analysis, observed invited discussant Carolyn S. P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, National Heart Centre, Singapore, after the Dr. Mentz presentation.

Sacubitril-valsartan should be started only in stabilized patients, she emphasized. It should be delayed in those “with ongoing adjustments of antihypertensives, diuretics, and so on,” in whom premature initiation of the drug may promote symptomatic hypotension. Should that happen, Dr. Lam cautioned, there’s a risk that such patients would be “mislabeled as intolerant” of the ARNI and so wouldn’t be started on it later.

The pooled PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF analysis, Dr. Lam proposed, might also help overcome the “clinical inertia and fear” that is slowing the uptake of early guideline-directed drug therapy initiation in patients hospitalized with HF.

LVEF spectrum across two studies

As Dr. Mentz reported, the analysis included 881 and 466 patients from PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, respectively. Of the total, 673 were assigned to receive valsartan and 674 to receive either enalapril or valsartan. Overall, 36% of the population were women.

Patients in PIONEER-HF, with an LVEF 40% or lower, were started on their assigned drug during an acute-HF hospitalization and followed a median of 8 weeks. PARAGLIDE-HF patients, with LVEF higher than 40%, started therapy either in hospital (in 70% of cases) or within 30 days of their HF event; they were followed a median of 6 months.

Hazard ratios for outcomes in the sacubitril-valsartan group vs. those on ACE inhibitors or ARBs were 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.83; P < .0001 for change in NT-proBNP levels. For the composite of CV death or HF hospitalization, HRs were as follows:

- 0.70 (95% CI, 0.54-0.91; P = .0077) overall.

- 0.59 (95% CI, 0.44-0.79) for LVEF < 60%.

- 1.53 (95% CI, 0.80-2.91) for LVEF > 60%.

Current guidelines, Dr. Mentz noted, recommend that sacubitril-valsartan “be initiated de novo” predischarge in patients without contraindications who are hospitalized with acute HF with reduced LVEF. The combined analysis of PIONEER-HF and PARAGLIDE-HF, he said, potentially extends the recommendation “across the ejection fraction spectrum.”

Dr. Mentz has received research support and honoraria from Abbott, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Fast BioMedical, Gilead, Innolife, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Medable, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Respicardia, Roche, Sanofi, Vifor, Windtree Therapeutics, and Zoll. Dr. Lam has reported financial relationships “with more than 25 pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, many of which produce therapies for heart failure,” as well as with Medscape/WebMD Global LLC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT HFSA 2023

Hopeful insights, no overall HFpEF gains from splanchnic nerve ablation: REBALANCE-HF

It’s still early days for a potential transcatheter technique that tones down sympathetic activation mediating blood volume shifts to the heart and lungs. Such volume transfers can contribute to congestion and acute decompensation in some patients with heart failure. But a randomized trial with negative overall results still may have moved the novel procedure a modest step forward.

The procedure, right-sided splanchnic-nerve ablation for volume management (SAVM), failed to show significant effects on hemodynamics, exercise capacity, natriuretic peptides, or quality of life in a trial covering a broad population of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study, called REBALANCE-HF, compared ablation of the right greater splanchnic nerve with a sham version of the procedure for any effects on hemodynamic or functional outcomes.

Among such “potential responders,” those undergoing SAVM trended better than patients receiving the sham procedure with respect to hemodynamic, functional, natriuretic peptide, and quality of life endpoints.

The potential predictors of SAVM success included elevated or preserved cardiac output and pulse pressure with exercise or on standing up; appropriate heart-rate exercise responses; and little or no echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction.

The panel of features might potentially identify patients more likely to respond to the procedure and perhaps sharpen entry criteria in future clinical trials, Marat Fudim, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Dr. Fudim presented the REBALANCE-HF findings at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

How SAVM works

Sympathetic activation can lead to acute or chronic constriction of vessels in the splanchnic bed within the upper and lower abdomen, one of the body’s largest blood reservoirs, Dr. Fudim explained. Resulting volume shifts to the general circulation, and therefore the heart and lungs, are a normal exercise response that, in HF, can fall out of balance and excessively raise cardiac filling pressure.

Lessened sympathetic tone after unilateral GNS ablation can promote splanchnic venous dilation that reduces intrathoracic blood volume, potentially averting congestion, and decompensation, observed Kavita Sharma, MD, invited discussant for Dr. Fudim’s presentation.

The trial’s potential-responder cohort “seemed able to augment cardiac output in response to stress” and to “maintain or augment their orthostatic pulse pressure,” more effectively than the other participants, said Dr. Sharma, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although the trial was overall negative for 1-month change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), the primary efficacy endpoint, Dr. Sharma said, it confirmed SAVM as a safe procedure in HFpEF and “ensured its replicability and technical success.”

Future studies should explore ways to characterize unlikely SAVM responders, she proposed. “I would argue these patients are probably more important than even the responders.”

Yet it’s unknown why, for example, cardiac output wouldn’t increase with exercise in a patient with HFpEF. “Is it related to preload insufficiency, right ventricular failure, atrial myopathy, perhaps more restrictive physiology, chronotropic incompetence, or medications – or a combination of the above?”

REBALANCE-HF assigned 90 patients with HFpEF to either the active or sham SAVM groups, 44 and 46 patients, respectively. To be eligible, patients were stable on HF meds and had either elevated natriuretic peptides or, within the past year, at least one HF hospitalization or escalation of intravenous diuretics for worsening HF.

The active and sham control groups fared similarly for the primary PCWP endpoint and for the secondary endpoints of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and natriuretic peptide levels at 6 and 12 months.

Predicting SAVM response

In analysis limited to potential responders, PCWP, KCCQ, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide outcomes for patients were combined into z scores, a single metric that reflects multiple outcomes, Dr. Fudim explained.

The z scores were derived for tertiles of patients in subgroups defined by a range of parameters that included demographics, medical history, and hemodynamic and echocardiographic variables.

Four such variables were found to interact across tertiles in a way that suggested their value as SAVM outcome predictors and were then used to select the cohort of potential responders. The variables were exertion-related changes in cardiac index, pulse pressure, and heart rate, and mitral E/A ratio – the latter a measure of diastolic dysfunction.

Among potential responders, those who underwent SAVM showed a 2.9–mm Hg steeper drop in peak PCWP at 1 month (P = .02), compared with patients getting the sham procedure.

They also bested control patients at both 6 and 12 months for KCCQ score, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide levels, the latter of which fell in the SAVM group and climbed in control patients at both follow-ups.

“Hypothetically, it makes sense” to target the splanchnic nerve in HFpEF, and indeed in HF with reduced ejection fraction, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

And should SAVM enter the mainstream, it would definitely be important to identify “the right” patients for such an invasive procedure, those likely to show “efficacy with a good safety margin,” said Dr. Bozkurt, who was not associated with REBALANCE-HF.

But the trial, she said, “unfortunately did not give real signals of outcome benefit.”

REBALANCE-HF was supported by Axon Therapies. Dr. Fudim disclosed consulting, receiving royalties, or having ownership or equity in Axon Therapies. Dr. Sharma disclosed receiving honoraria for speaking from Novartis and Janssen and serving on an advisory board or consulting for Novartis, Janssen, and Bayer. Dr. Bozkurt disclosed receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Baxter Health Care, and Sanofi Aventis and having other relationships with Renovacor, Respicardia, Abbott Vascular, Liva Nova, Vifor, and Cardurion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s still early days for a potential transcatheter technique that tones down sympathetic activation mediating blood volume shifts to the heart and lungs. Such volume transfers can contribute to congestion and acute decompensation in some patients with heart failure. But a randomized trial with negative overall results still may have moved the novel procedure a modest step forward.

The procedure, right-sided splanchnic-nerve ablation for volume management (SAVM), failed to show significant effects on hemodynamics, exercise capacity, natriuretic peptides, or quality of life in a trial covering a broad population of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study, called REBALANCE-HF, compared ablation of the right greater splanchnic nerve with a sham version of the procedure for any effects on hemodynamic or functional outcomes.

Among such “potential responders,” those undergoing SAVM trended better than patients receiving the sham procedure with respect to hemodynamic, functional, natriuretic peptide, and quality of life endpoints.

The potential predictors of SAVM success included elevated or preserved cardiac output and pulse pressure with exercise or on standing up; appropriate heart-rate exercise responses; and little or no echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction.

The panel of features might potentially identify patients more likely to respond to the procedure and perhaps sharpen entry criteria in future clinical trials, Marat Fudim, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Dr. Fudim presented the REBALANCE-HF findings at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

How SAVM works

Sympathetic activation can lead to acute or chronic constriction of vessels in the splanchnic bed within the upper and lower abdomen, one of the body’s largest blood reservoirs, Dr. Fudim explained. Resulting volume shifts to the general circulation, and therefore the heart and lungs, are a normal exercise response that, in HF, can fall out of balance and excessively raise cardiac filling pressure.

Lessened sympathetic tone after unilateral GNS ablation can promote splanchnic venous dilation that reduces intrathoracic blood volume, potentially averting congestion, and decompensation, observed Kavita Sharma, MD, invited discussant for Dr. Fudim’s presentation.

The trial’s potential-responder cohort “seemed able to augment cardiac output in response to stress” and to “maintain or augment their orthostatic pulse pressure,” more effectively than the other participants, said Dr. Sharma, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although the trial was overall negative for 1-month change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), the primary efficacy endpoint, Dr. Sharma said, it confirmed SAVM as a safe procedure in HFpEF and “ensured its replicability and technical success.”

Future studies should explore ways to characterize unlikely SAVM responders, she proposed. “I would argue these patients are probably more important than even the responders.”

Yet it’s unknown why, for example, cardiac output wouldn’t increase with exercise in a patient with HFpEF. “Is it related to preload insufficiency, right ventricular failure, atrial myopathy, perhaps more restrictive physiology, chronotropic incompetence, or medications – or a combination of the above?”

REBALANCE-HF assigned 90 patients with HFpEF to either the active or sham SAVM groups, 44 and 46 patients, respectively. To be eligible, patients were stable on HF meds and had either elevated natriuretic peptides or, within the past year, at least one HF hospitalization or escalation of intravenous diuretics for worsening HF.

The active and sham control groups fared similarly for the primary PCWP endpoint and for the secondary endpoints of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and natriuretic peptide levels at 6 and 12 months.

Predicting SAVM response

In analysis limited to potential responders, PCWP, KCCQ, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide outcomes for patients were combined into z scores, a single metric that reflects multiple outcomes, Dr. Fudim explained.

The z scores were derived for tertiles of patients in subgroups defined by a range of parameters that included demographics, medical history, and hemodynamic and echocardiographic variables.

Four such variables were found to interact across tertiles in a way that suggested their value as SAVM outcome predictors and were then used to select the cohort of potential responders. The variables were exertion-related changes in cardiac index, pulse pressure, and heart rate, and mitral E/A ratio – the latter a measure of diastolic dysfunction.

Among potential responders, those who underwent SAVM showed a 2.9–mm Hg steeper drop in peak PCWP at 1 month (P = .02), compared with patients getting the sham procedure.

They also bested control patients at both 6 and 12 months for KCCQ score, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide levels, the latter of which fell in the SAVM group and climbed in control patients at both follow-ups.

“Hypothetically, it makes sense” to target the splanchnic nerve in HFpEF, and indeed in HF with reduced ejection fraction, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

And should SAVM enter the mainstream, it would definitely be important to identify “the right” patients for such an invasive procedure, those likely to show “efficacy with a good safety margin,” said Dr. Bozkurt, who was not associated with REBALANCE-HF.

But the trial, she said, “unfortunately did not give real signals of outcome benefit.”

REBALANCE-HF was supported by Axon Therapies. Dr. Fudim disclosed consulting, receiving royalties, or having ownership or equity in Axon Therapies. Dr. Sharma disclosed receiving honoraria for speaking from Novartis and Janssen and serving on an advisory board or consulting for Novartis, Janssen, and Bayer. Dr. Bozkurt disclosed receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Baxter Health Care, and Sanofi Aventis and having other relationships with Renovacor, Respicardia, Abbott Vascular, Liva Nova, Vifor, and Cardurion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s still early days for a potential transcatheter technique that tones down sympathetic activation mediating blood volume shifts to the heart and lungs. Such volume transfers can contribute to congestion and acute decompensation in some patients with heart failure. But a randomized trial with negative overall results still may have moved the novel procedure a modest step forward.

The procedure, right-sided splanchnic-nerve ablation for volume management (SAVM), failed to show significant effects on hemodynamics, exercise capacity, natriuretic peptides, or quality of life in a trial covering a broad population of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study, called REBALANCE-HF, compared ablation of the right greater splanchnic nerve with a sham version of the procedure for any effects on hemodynamic or functional outcomes.

Among such “potential responders,” those undergoing SAVM trended better than patients receiving the sham procedure with respect to hemodynamic, functional, natriuretic peptide, and quality of life endpoints.

The potential predictors of SAVM success included elevated or preserved cardiac output and pulse pressure with exercise or on standing up; appropriate heart-rate exercise responses; and little or no echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction.

The panel of features might potentially identify patients more likely to respond to the procedure and perhaps sharpen entry criteria in future clinical trials, Marat Fudim, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Dr. Fudim presented the REBALANCE-HF findings at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

How SAVM works

Sympathetic activation can lead to acute or chronic constriction of vessels in the splanchnic bed within the upper and lower abdomen, one of the body’s largest blood reservoirs, Dr. Fudim explained. Resulting volume shifts to the general circulation, and therefore the heart and lungs, are a normal exercise response that, in HF, can fall out of balance and excessively raise cardiac filling pressure.

Lessened sympathetic tone after unilateral GNS ablation can promote splanchnic venous dilation that reduces intrathoracic blood volume, potentially averting congestion, and decompensation, observed Kavita Sharma, MD, invited discussant for Dr. Fudim’s presentation.

The trial’s potential-responder cohort “seemed able to augment cardiac output in response to stress” and to “maintain or augment their orthostatic pulse pressure,” more effectively than the other participants, said Dr. Sharma, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Although the trial was overall negative for 1-month change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), the primary efficacy endpoint, Dr. Sharma said, it confirmed SAVM as a safe procedure in HFpEF and “ensured its replicability and technical success.”

Future studies should explore ways to characterize unlikely SAVM responders, she proposed. “I would argue these patients are probably more important than even the responders.”

Yet it’s unknown why, for example, cardiac output wouldn’t increase with exercise in a patient with HFpEF. “Is it related to preload insufficiency, right ventricular failure, atrial myopathy, perhaps more restrictive physiology, chronotropic incompetence, or medications – or a combination of the above?”

REBALANCE-HF assigned 90 patients with HFpEF to either the active or sham SAVM groups, 44 and 46 patients, respectively. To be eligible, patients were stable on HF meds and had either elevated natriuretic peptides or, within the past year, at least one HF hospitalization or escalation of intravenous diuretics for worsening HF.

The active and sham control groups fared similarly for the primary PCWP endpoint and for the secondary endpoints of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and natriuretic peptide levels at 6 and 12 months.

Predicting SAVM response

In analysis limited to potential responders, PCWP, KCCQ, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide outcomes for patients were combined into z scores, a single metric that reflects multiple outcomes, Dr. Fudim explained.

The z scores were derived for tertiles of patients in subgroups defined by a range of parameters that included demographics, medical history, and hemodynamic and echocardiographic variables.

Four such variables were found to interact across tertiles in a way that suggested their value as SAVM outcome predictors and were then used to select the cohort of potential responders. The variables were exertion-related changes in cardiac index, pulse pressure, and heart rate, and mitral E/A ratio – the latter a measure of diastolic dysfunction.

Among potential responders, those who underwent SAVM showed a 2.9–mm Hg steeper drop in peak PCWP at 1 month (P = .02), compared with patients getting the sham procedure.

They also bested control patients at both 6 and 12 months for KCCQ score, 6MWD, and natriuretic peptide levels, the latter of which fell in the SAVM group and climbed in control patients at both follow-ups.

“Hypothetically, it makes sense” to target the splanchnic nerve in HFpEF, and indeed in HF with reduced ejection fraction, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

And should SAVM enter the mainstream, it would definitely be important to identify “the right” patients for such an invasive procedure, those likely to show “efficacy with a good safety margin,” said Dr. Bozkurt, who was not associated with REBALANCE-HF.

But the trial, she said, “unfortunately did not give real signals of outcome benefit.”

REBALANCE-HF was supported by Axon Therapies. Dr. Fudim disclosed consulting, receiving royalties, or having ownership or equity in Axon Therapies. Dr. Sharma disclosed receiving honoraria for speaking from Novartis and Janssen and serving on an advisory board or consulting for Novartis, Janssen, and Bayer. Dr. Bozkurt disclosed receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Baxter Health Care, and Sanofi Aventis and having other relationships with Renovacor, Respicardia, Abbott Vascular, Liva Nova, Vifor, and Cardurion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HFSA 2023

Spreading out daily meals and snacks may boost heart failure survival

CLEVELAND – , an observational study suggests.

The new findings, based primarily on 15 years of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), may argue against time-restricted diet interventions like intermittent fasting for patients with HF, researchers say.

The study’s nearly 1,000 participants on medical therapy for HF reported a mean daily eating window of 11 hours and daily average of four “eating occasions,” defined as meals or snacks of at least 50 kcal.

A daily eating window of 11 or more hours, compared with less than 11 hours, corresponded to a greater than 40% drop in risk for CV mortality (P = .013) over 5-6 years, reported Hayley E. Billingsley, RD, CEP, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va,, at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The analysis adjusted for caloric intake, daily number of eating occasions, body mass index (BMI), history of CV disease and cancer, diabetes, and a slew of other potential confounders.

Prior evidence, mostly from healthy people, has suggested that extended fasting during the day is associated with less physical activity, Ms. Billingsley said in an interview. So it may be that people with HF who spread out their calorie intake are more active throughout the day.

A longer time window for eating, therefore, may have indirect metabolic benefits and help preserve their lean body mass, possibly reducing CV risk in a patient group at risk for muscle wasting.

The findings add to earlier evidence from Ms. Billingsley’s center that suggests that expanded daily time windows for eating, especially later final food rather than earlier first food, may help boost CV fitness for patients with obesity and HF with preserved ejection fraction.

Intermittent fasting and other practices involving the timing of food intake have been studied for weight loss and metabolic health in mostly healthy people and patients with diabetes, she noted. “But it’s really underexplored in people with established cardiovascular disease.”

On the basis of admittedly “very preliminary” findings, it may be that some patients should not shorten their daily time windows for eating or engage in intermittent fasting, Ms. Billingsley said. It’s probably worth considering, before the approach is recommended, “what their risk is for malnutrition or sarcopenia.”

The current study included 991 persons who entered the NHANES database from 2003 to 2018. The patients self-identified as having HF, reported taking medications commonly prescribed in HF, and provided at least two “reliable” dietary recalls.

The average age of the patients was 68 years, and they had had HF for a mean of 9.5 years; 47% were women, three-fourths were White persons, two thirds had dyslipidemia, and a quarter had a history of cancer.

On average, their first eating occasion of the day was at about 8:30 a.m., and the last occasion was at about 7:30 p.m., for a time window of about 11 hours; daily calorie consumption averaged about 1,830 kcal.

About 52% died over the mean follow-up of 69 months; about 44% of deaths were from CV causes.

In a model adjusted for demographics, BMI, smoking status, times of eating occasions, CV disease, diabetes, and cancer history, the all-cause mortality hazard ratio for time windows ≥ 11 hours vs. < 11 hours was 0.236 (95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.715; P = .011).

The reduction was no longer significant on further adjustment for duration of HF, a score reflecting difficulty walking, nightly hours of sleep (which averaged 7.2 hours), daily number of eating occasions, and caloric intake, Ms. Billingsley reported.

But in the fully adjusted analysis, the HR for CV mortality for the longer vs. shorter time window was 0.368 (95% CI, 0.169-0.803; P = .013).

The issue deserves further exploration in a randomized trial, Ms. Billingsley proposed, perhaps one in which patients with HF wear accelerometers to track daily activity levels. “We’d love to do a pilot study of extending their eating window that really digs into what the mechanism of any benefit might be if we assign them to a longer time window and whether it’s related to physical activity.”

Ms. Billingsley reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – , an observational study suggests.

The new findings, based primarily on 15 years of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), may argue against time-restricted diet interventions like intermittent fasting for patients with HF, researchers say.

The study’s nearly 1,000 participants on medical therapy for HF reported a mean daily eating window of 11 hours and daily average of four “eating occasions,” defined as meals or snacks of at least 50 kcal.

A daily eating window of 11 or more hours, compared with less than 11 hours, corresponded to a greater than 40% drop in risk for CV mortality (P = .013) over 5-6 years, reported Hayley E. Billingsley, RD, CEP, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va,, at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The analysis adjusted for caloric intake, daily number of eating occasions, body mass index (BMI), history of CV disease and cancer, diabetes, and a slew of other potential confounders.

Prior evidence, mostly from healthy people, has suggested that extended fasting during the day is associated with less physical activity, Ms. Billingsley said in an interview. So it may be that people with HF who spread out their calorie intake are more active throughout the day.

A longer time window for eating, therefore, may have indirect metabolic benefits and help preserve their lean body mass, possibly reducing CV risk in a patient group at risk for muscle wasting.

The findings add to earlier evidence from Ms. Billingsley’s center that suggests that expanded daily time windows for eating, especially later final food rather than earlier first food, may help boost CV fitness for patients with obesity and HF with preserved ejection fraction.

Intermittent fasting and other practices involving the timing of food intake have been studied for weight loss and metabolic health in mostly healthy people and patients with diabetes, she noted. “But it’s really underexplored in people with established cardiovascular disease.”

On the basis of admittedly “very preliminary” findings, it may be that some patients should not shorten their daily time windows for eating or engage in intermittent fasting, Ms. Billingsley said. It’s probably worth considering, before the approach is recommended, “what their risk is for malnutrition or sarcopenia.”

The current study included 991 persons who entered the NHANES database from 2003 to 2018. The patients self-identified as having HF, reported taking medications commonly prescribed in HF, and provided at least two “reliable” dietary recalls.

The average age of the patients was 68 years, and they had had HF for a mean of 9.5 years; 47% were women, three-fourths were White persons, two thirds had dyslipidemia, and a quarter had a history of cancer.

On average, their first eating occasion of the day was at about 8:30 a.m., and the last occasion was at about 7:30 p.m., for a time window of about 11 hours; daily calorie consumption averaged about 1,830 kcal.

About 52% died over the mean follow-up of 69 months; about 44% of deaths were from CV causes.

In a model adjusted for demographics, BMI, smoking status, times of eating occasions, CV disease, diabetes, and cancer history, the all-cause mortality hazard ratio for time windows ≥ 11 hours vs. < 11 hours was 0.236 (95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.715; P = .011).

The reduction was no longer significant on further adjustment for duration of HF, a score reflecting difficulty walking, nightly hours of sleep (which averaged 7.2 hours), daily number of eating occasions, and caloric intake, Ms. Billingsley reported.

But in the fully adjusted analysis, the HR for CV mortality for the longer vs. shorter time window was 0.368 (95% CI, 0.169-0.803; P = .013).

The issue deserves further exploration in a randomized trial, Ms. Billingsley proposed, perhaps one in which patients with HF wear accelerometers to track daily activity levels. “We’d love to do a pilot study of extending their eating window that really digs into what the mechanism of any benefit might be if we assign them to a longer time window and whether it’s related to physical activity.”

Ms. Billingsley reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – , an observational study suggests.

The new findings, based primarily on 15 years of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), may argue against time-restricted diet interventions like intermittent fasting for patients with HF, researchers say.

The study’s nearly 1,000 participants on medical therapy for HF reported a mean daily eating window of 11 hours and daily average of four “eating occasions,” defined as meals or snacks of at least 50 kcal.

A daily eating window of 11 or more hours, compared with less than 11 hours, corresponded to a greater than 40% drop in risk for CV mortality (P = .013) over 5-6 years, reported Hayley E. Billingsley, RD, CEP, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va,, at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The analysis adjusted for caloric intake, daily number of eating occasions, body mass index (BMI), history of CV disease and cancer, diabetes, and a slew of other potential confounders.

Prior evidence, mostly from healthy people, has suggested that extended fasting during the day is associated with less physical activity, Ms. Billingsley said in an interview. So it may be that people with HF who spread out their calorie intake are more active throughout the day.

A longer time window for eating, therefore, may have indirect metabolic benefits and help preserve their lean body mass, possibly reducing CV risk in a patient group at risk for muscle wasting.

The findings add to earlier evidence from Ms. Billingsley’s center that suggests that expanded daily time windows for eating, especially later final food rather than earlier first food, may help boost CV fitness for patients with obesity and HF with preserved ejection fraction.

Intermittent fasting and other practices involving the timing of food intake have been studied for weight loss and metabolic health in mostly healthy people and patients with diabetes, she noted. “But it’s really underexplored in people with established cardiovascular disease.”

On the basis of admittedly “very preliminary” findings, it may be that some patients should not shorten their daily time windows for eating or engage in intermittent fasting, Ms. Billingsley said. It’s probably worth considering, before the approach is recommended, “what their risk is for malnutrition or sarcopenia.”

The current study included 991 persons who entered the NHANES database from 2003 to 2018. The patients self-identified as having HF, reported taking medications commonly prescribed in HF, and provided at least two “reliable” dietary recalls.

The average age of the patients was 68 years, and they had had HF for a mean of 9.5 years; 47% were women, three-fourths were White persons, two thirds had dyslipidemia, and a quarter had a history of cancer.

On average, their first eating occasion of the day was at about 8:30 a.m., and the last occasion was at about 7:30 p.m., for a time window of about 11 hours; daily calorie consumption averaged about 1,830 kcal.

About 52% died over the mean follow-up of 69 months; about 44% of deaths were from CV causes.

In a model adjusted for demographics, BMI, smoking status, times of eating occasions, CV disease, diabetes, and cancer history, the all-cause mortality hazard ratio for time windows ≥ 11 hours vs. < 11 hours was 0.236 (95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.715; P = .011).

The reduction was no longer significant on further adjustment for duration of HF, a score reflecting difficulty walking, nightly hours of sleep (which averaged 7.2 hours), daily number of eating occasions, and caloric intake, Ms. Billingsley reported.

But in the fully adjusted analysis, the HR for CV mortality for the longer vs. shorter time window was 0.368 (95% CI, 0.169-0.803; P = .013).

The issue deserves further exploration in a randomized trial, Ms. Billingsley proposed, perhaps one in which patients with HF wear accelerometers to track daily activity levels. “We’d love to do a pilot study of extending their eating window that really digs into what the mechanism of any benefit might be if we assign them to a longer time window and whether it’s related to physical activity.”

Ms. Billingsley reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT HFSA 2023

Semaglutide win in HFpEF with obesity regardless of ejection fraction: STEP-HFpEF

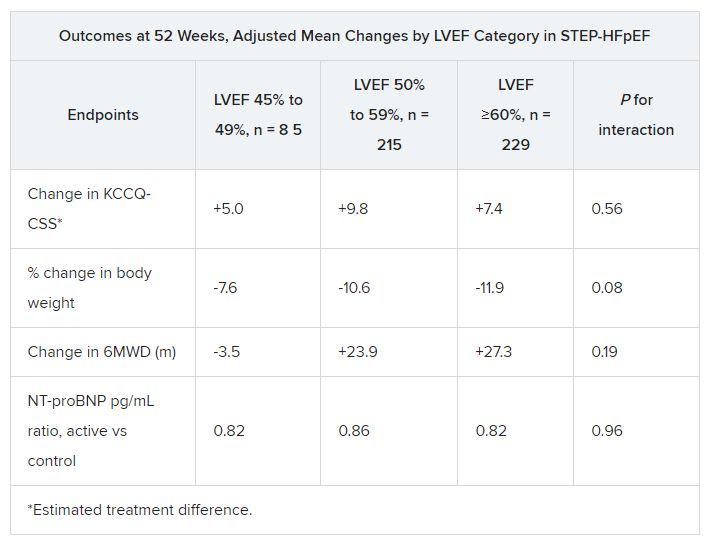

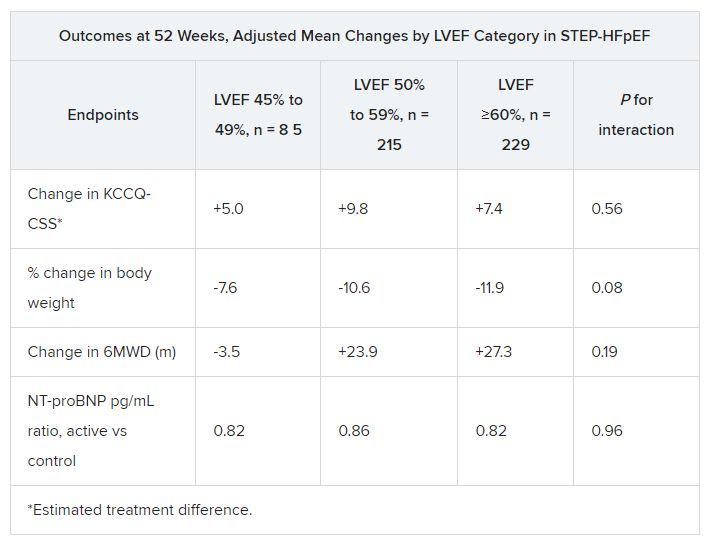

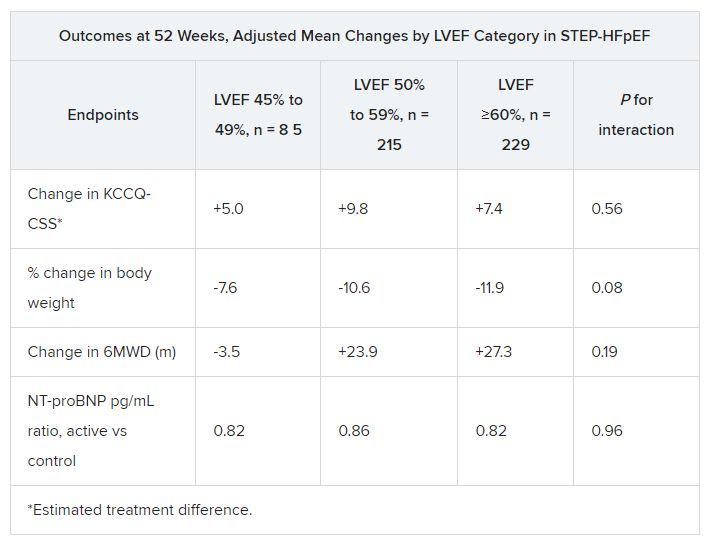

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT HFSA 2023