User login

Study pinpoints best predictor of when reflux symptoms don’t require PPI

Four days is an optimal time for wireless reflux monitoring to determine which patients can stop taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and which ones need long-term antireflux therapy, researchers report.

“This first-of-its kind double-blinded clinical trial demonstrates the comparable, and in some cases better, performance of a simple assessment of daily acid exposure from multiple days of recording compared to other composite or complex assessments,” write Rena Yadlapati, MD, with the Division of Gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, and her coauthors.

Their findings were published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

A substantial percentage of patients who have esophageal reflux symptoms do not have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and can stop taking PPIs.

Wireless reflux monitoring performed while patients are not taking PPIs is the gold standard for determining whether a patient has abnormal acid from GERD, but the optimal daily acid exposure time (AET) and the optimal duration of monitoring have not been well studied.

Aiming to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Yadlapati and her colleagues conducted a single-arm, double-blinded clinical trial over 4 years at two tertiary care centers. They enrolled adult patients who had demonstrated an inadequate response to more than 8 weeks’ treatment with PPIs.

Study participants were asked to stop taking their PPI for 3 weeks in order for the investigators to determine the rate of relapse after PPI use and establish the study reference standard to discontinue therapy. During the 3-week period, after having stopped taking PPIs for at least a week, patients underwent 96-hour wireless reflux monitoring. They were then told to continue not taking PPIs for an additional 2 weeks. They could use over-the-counter antacids for symptom relief.

The primary outcome was whether PPIs could be successfully discontinued or restarted within 3 weeks. Of the 132 patients, 30% were able to stop taking PPIs.

AET less than 4.0% best discontinuation predictor

The team came to two key conclusions.

They found that acid exposure time of less than 4.0% was the best predictor of when stopping PPIs will be effective without worsening symptoms (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-6.4). Comparatively, 45% (22 of 49 patients) with total AET of 4.0% or less discontinued taking PPIs, versus 22% (18 of 83 patients) with total AET of more than 4.0%.

Additionally, the investigators concluded that 96 hours of monitoring was better than 48 hours or fewer in predicting whether patients could stop taking PPIs (area under curve [AUC] for 96 hours, 0.63, versus AUC for 48 hours, 0.57).

Dr. Yadlapati told this news organization that the findings should be practice-changing.

“You really need to test for 4 days,” she said. She noted that the battery life of the monitor is 96 hours, and clinicians commonly only test for 2 days.

With only 1-2 days of monitoring, there is too much variability in how much acid is in the esophagus from one day to another. Monitoring over a 4-day period gives a clearer picture of acid exposure burden, she said.

Her advice: “If you have a patient with heartburn or chest pain and you think it might be from reflux, and they’re not responding to a trial of PPI, get the reflux monitoring. Don’t wait.”

After 4 days of monitoring, if exposure to acid is low, “they should really be taken off their PPI therapy,” she said.

They likely have a condition that requires a different therapy, she added.

“It is very consistent with what we have thought to be the case and what some lower-quality studies have shown,” she said. “It just hadn’t been done in a clinical trial with a large patient population and with a full outcome.”

PPI often used inappropriately

Interest is high both in discontinuing PPI in light of widespread and often inappropriate use and in not starting treatment with PPIs for patients who need a different therapy.

As this news organization has reported, some studies have linked long-term PPI use with intestinal infections, pneumonia, stomach cancer, osteoporosis-related bone fractures, chronic kidney disease, vitamin deficiencies, heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and early death.

Avin Aggarwal, MD, a gastroenterologist and medical director of Banner Health’s South Campus endoscopy services and clinical assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that this study provides the evidence needed to push for practice change.

He said his center has been using 48-hour reflux monitoring. He said that anecdotally, they had gotten better data with 4-day monitoring, but evidence was not directly tied to a measurable outcome such as this study provides.

With 4-day monitoring, “we get way more symptoms on the recorder to actually correlate them with reflux or not,” he said.

He said he will now push for the 96-hour monitoring in his clinic.

He added that part of the problem is in assuming patients have GERD and initiating PPIs in the first place without a specific diagnosis of acid reflux.

Patients, he said, are often aware of the long-term side effects of PPIs and are approaching their physicians to see whether they can discontinue them.

The data from this study, he said, will help guide physicians on when it is appropriate to discontinue treatment.

Dr. Yadlapati is a consultant for Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and StatLinkMD and receives research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She is on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix. Other study coauthors report ties to Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, Iso-Thrive, Quintiles, Johnson & Johnson, Reckitt, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Daewood, Takeda, and Crospon. Study coauthor Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PHD, holds a patent on mucosal integrity by Vanderbilt. Dr. Aggarwal reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four days is an optimal time for wireless reflux monitoring to determine which patients can stop taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and which ones need long-term antireflux therapy, researchers report.

“This first-of-its kind double-blinded clinical trial demonstrates the comparable, and in some cases better, performance of a simple assessment of daily acid exposure from multiple days of recording compared to other composite or complex assessments,” write Rena Yadlapati, MD, with the Division of Gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, and her coauthors.

Their findings were published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

A substantial percentage of patients who have esophageal reflux symptoms do not have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and can stop taking PPIs.

Wireless reflux monitoring performed while patients are not taking PPIs is the gold standard for determining whether a patient has abnormal acid from GERD, but the optimal daily acid exposure time (AET) and the optimal duration of monitoring have not been well studied.

Aiming to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Yadlapati and her colleagues conducted a single-arm, double-blinded clinical trial over 4 years at two tertiary care centers. They enrolled adult patients who had demonstrated an inadequate response to more than 8 weeks’ treatment with PPIs.

Study participants were asked to stop taking their PPI for 3 weeks in order for the investigators to determine the rate of relapse after PPI use and establish the study reference standard to discontinue therapy. During the 3-week period, after having stopped taking PPIs for at least a week, patients underwent 96-hour wireless reflux monitoring. They were then told to continue not taking PPIs for an additional 2 weeks. They could use over-the-counter antacids for symptom relief.

The primary outcome was whether PPIs could be successfully discontinued or restarted within 3 weeks. Of the 132 patients, 30% were able to stop taking PPIs.

AET less than 4.0% best discontinuation predictor

The team came to two key conclusions.

They found that acid exposure time of less than 4.0% was the best predictor of when stopping PPIs will be effective without worsening symptoms (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-6.4). Comparatively, 45% (22 of 49 patients) with total AET of 4.0% or less discontinued taking PPIs, versus 22% (18 of 83 patients) with total AET of more than 4.0%.

Additionally, the investigators concluded that 96 hours of monitoring was better than 48 hours or fewer in predicting whether patients could stop taking PPIs (area under curve [AUC] for 96 hours, 0.63, versus AUC for 48 hours, 0.57).

Dr. Yadlapati told this news organization that the findings should be practice-changing.

“You really need to test for 4 days,” she said. She noted that the battery life of the monitor is 96 hours, and clinicians commonly only test for 2 days.

With only 1-2 days of monitoring, there is too much variability in how much acid is in the esophagus from one day to another. Monitoring over a 4-day period gives a clearer picture of acid exposure burden, she said.

Her advice: “If you have a patient with heartburn or chest pain and you think it might be from reflux, and they’re not responding to a trial of PPI, get the reflux monitoring. Don’t wait.”

After 4 days of monitoring, if exposure to acid is low, “they should really be taken off their PPI therapy,” she said.

They likely have a condition that requires a different therapy, she added.

“It is very consistent with what we have thought to be the case and what some lower-quality studies have shown,” she said. “It just hadn’t been done in a clinical trial with a large patient population and with a full outcome.”

PPI often used inappropriately

Interest is high both in discontinuing PPI in light of widespread and often inappropriate use and in not starting treatment with PPIs for patients who need a different therapy.

As this news organization has reported, some studies have linked long-term PPI use with intestinal infections, pneumonia, stomach cancer, osteoporosis-related bone fractures, chronic kidney disease, vitamin deficiencies, heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and early death.

Avin Aggarwal, MD, a gastroenterologist and medical director of Banner Health’s South Campus endoscopy services and clinical assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that this study provides the evidence needed to push for practice change.

He said his center has been using 48-hour reflux monitoring. He said that anecdotally, they had gotten better data with 4-day monitoring, but evidence was not directly tied to a measurable outcome such as this study provides.

With 4-day monitoring, “we get way more symptoms on the recorder to actually correlate them with reflux or not,” he said.

He said he will now push for the 96-hour monitoring in his clinic.

He added that part of the problem is in assuming patients have GERD and initiating PPIs in the first place without a specific diagnosis of acid reflux.

Patients, he said, are often aware of the long-term side effects of PPIs and are approaching their physicians to see whether they can discontinue them.

The data from this study, he said, will help guide physicians on when it is appropriate to discontinue treatment.

Dr. Yadlapati is a consultant for Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and StatLinkMD and receives research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She is on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix. Other study coauthors report ties to Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, Iso-Thrive, Quintiles, Johnson & Johnson, Reckitt, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Daewood, Takeda, and Crospon. Study coauthor Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PHD, holds a patent on mucosal integrity by Vanderbilt. Dr. Aggarwal reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four days is an optimal time for wireless reflux monitoring to determine which patients can stop taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and which ones need long-term antireflux therapy, researchers report.

“This first-of-its kind double-blinded clinical trial demonstrates the comparable, and in some cases better, performance of a simple assessment of daily acid exposure from multiple days of recording compared to other composite or complex assessments,” write Rena Yadlapati, MD, with the Division of Gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, and her coauthors.

Their findings were published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

A substantial percentage of patients who have esophageal reflux symptoms do not have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and can stop taking PPIs.

Wireless reflux monitoring performed while patients are not taking PPIs is the gold standard for determining whether a patient has abnormal acid from GERD, but the optimal daily acid exposure time (AET) and the optimal duration of monitoring have not been well studied.

Aiming to fill this knowledge gap, Dr. Yadlapati and her colleagues conducted a single-arm, double-blinded clinical trial over 4 years at two tertiary care centers. They enrolled adult patients who had demonstrated an inadequate response to more than 8 weeks’ treatment with PPIs.

Study participants were asked to stop taking their PPI for 3 weeks in order for the investigators to determine the rate of relapse after PPI use and establish the study reference standard to discontinue therapy. During the 3-week period, after having stopped taking PPIs for at least a week, patients underwent 96-hour wireless reflux monitoring. They were then told to continue not taking PPIs for an additional 2 weeks. They could use over-the-counter antacids for symptom relief.

The primary outcome was whether PPIs could be successfully discontinued or restarted within 3 weeks. Of the 132 patients, 30% were able to stop taking PPIs.

AET less than 4.0% best discontinuation predictor

The team came to two key conclusions.

They found that acid exposure time of less than 4.0% was the best predictor of when stopping PPIs will be effective without worsening symptoms (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-6.4). Comparatively, 45% (22 of 49 patients) with total AET of 4.0% or less discontinued taking PPIs, versus 22% (18 of 83 patients) with total AET of more than 4.0%.

Additionally, the investigators concluded that 96 hours of monitoring was better than 48 hours or fewer in predicting whether patients could stop taking PPIs (area under curve [AUC] for 96 hours, 0.63, versus AUC for 48 hours, 0.57).

Dr. Yadlapati told this news organization that the findings should be practice-changing.

“You really need to test for 4 days,” she said. She noted that the battery life of the monitor is 96 hours, and clinicians commonly only test for 2 days.

With only 1-2 days of monitoring, there is too much variability in how much acid is in the esophagus from one day to another. Monitoring over a 4-day period gives a clearer picture of acid exposure burden, she said.

Her advice: “If you have a patient with heartburn or chest pain and you think it might be from reflux, and they’re not responding to a trial of PPI, get the reflux monitoring. Don’t wait.”

After 4 days of monitoring, if exposure to acid is low, “they should really be taken off their PPI therapy,” she said.

They likely have a condition that requires a different therapy, she added.

“It is very consistent with what we have thought to be the case and what some lower-quality studies have shown,” she said. “It just hadn’t been done in a clinical trial with a large patient population and with a full outcome.”

PPI often used inappropriately

Interest is high both in discontinuing PPI in light of widespread and often inappropriate use and in not starting treatment with PPIs for patients who need a different therapy.

As this news organization has reported, some studies have linked long-term PPI use with intestinal infections, pneumonia, stomach cancer, osteoporosis-related bone fractures, chronic kidney disease, vitamin deficiencies, heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and early death.

Avin Aggarwal, MD, a gastroenterologist and medical director of Banner Health’s South Campus endoscopy services and clinical assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview that this study provides the evidence needed to push for practice change.

He said his center has been using 48-hour reflux monitoring. He said that anecdotally, they had gotten better data with 4-day monitoring, but evidence was not directly tied to a measurable outcome such as this study provides.

With 4-day monitoring, “we get way more symptoms on the recorder to actually correlate them with reflux or not,” he said.

He said he will now push for the 96-hour monitoring in his clinic.

He added that part of the problem is in assuming patients have GERD and initiating PPIs in the first place without a specific diagnosis of acid reflux.

Patients, he said, are often aware of the long-term side effects of PPIs and are approaching their physicians to see whether they can discontinue them.

The data from this study, he said, will help guide physicians on when it is appropriate to discontinue treatment.

Dr. Yadlapati is a consultant for Medtronic, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and StatLinkMD and receives research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She is on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix. Other study coauthors report ties to Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, Iso-Thrive, Quintiles, Johnson & Johnson, Reckitt, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Daewood, Takeda, and Crospon. Study coauthor Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PHD, holds a patent on mucosal integrity by Vanderbilt. Dr. Aggarwal reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dyspepsia: A stepwise approach to evaluation and management

The global prevalence of dyspepsia is approximately 20%,1 and it is often associated with other comorbidities and overlapping gastrointestinal complaints. The effects on the patient’s quality of life, including societal impacts, are considerable. Symptoms and their response to treatment are highly variable, necessitating individualized management. While some patients’ symptoms may be refractory to standard medical treatment initially, evidence suggests that the strategies summarized in our guidance here—including the use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), prokinetics, and adjunctive therapies—may alleviate symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

What dyspepsia is—and what it isn’t

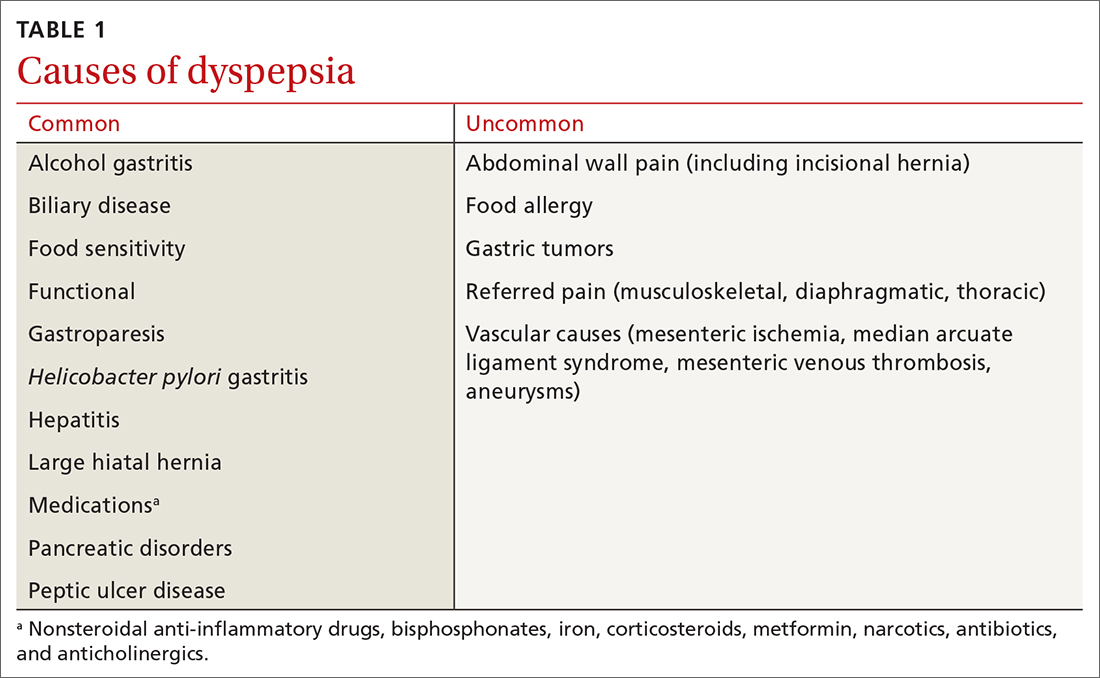

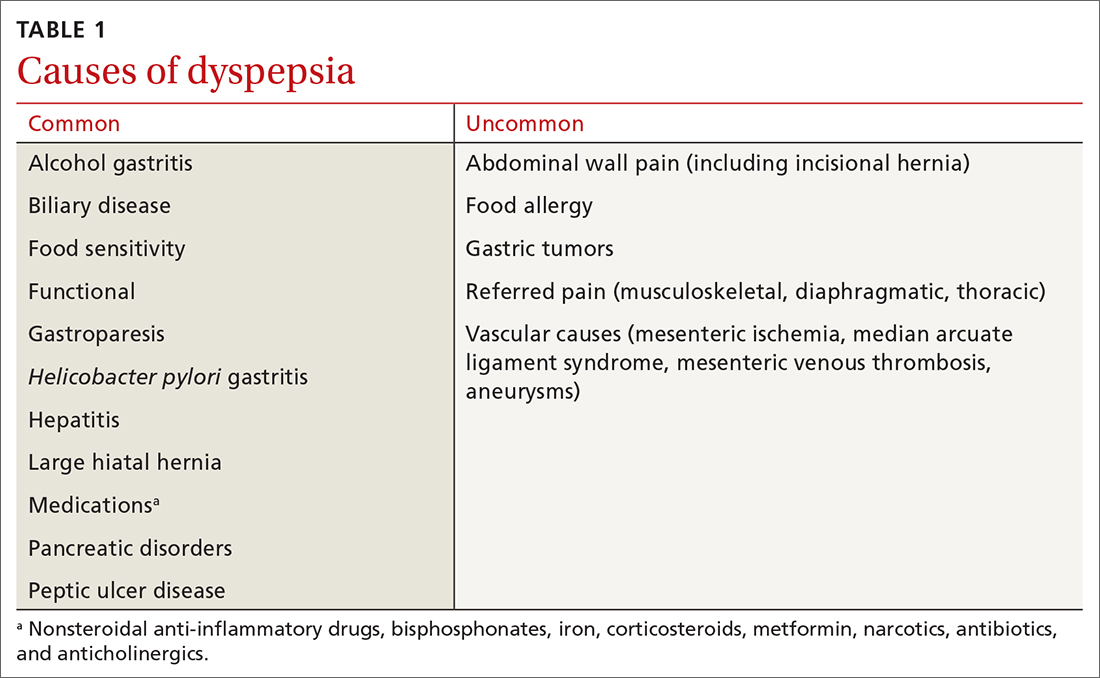

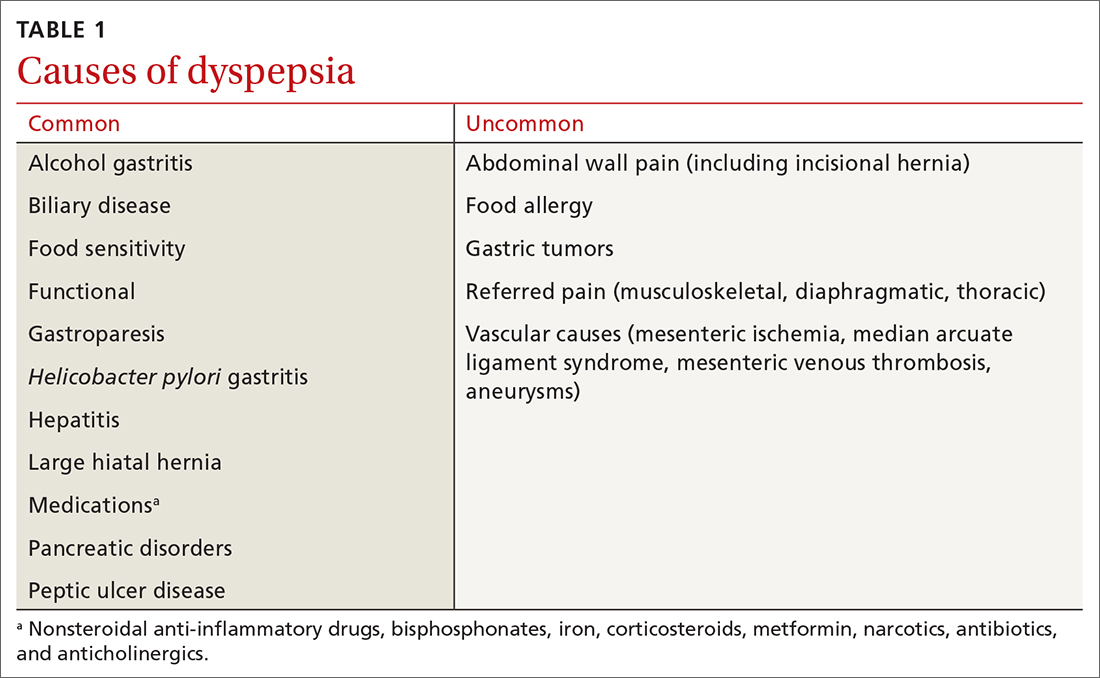

Dyspepsia is a poorly characterized disorder often associated with nausea, heartburn, early satiety, and bloating. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) now advocates using a clinically relevant definition of dyspepsia as “predominant epigastric pain lasting at least a month” as long as epigastric pain is the patient's primary complaint.2 Causes of dyspepsia are listed in TABLE 1.

Heartburn, a burning sensation in the chest, is not a dyspeptic symptom but the 2 may often coexist. In general, dyspepsia does not have a colicky or postural component. Symptoms that are relieved by evacuation of feces or gas generally should not be considered a part of dyspepsia.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a subset for which no structural pathology has been identified, accounting for up to 70% of all patients with dyspepsia.3 The Rome Foundation, in its recent update (Rome IV), has highlighted 4 key symptoms and 2 proposed subtypes (TABLE 2).4 The comorbidities of anxiety, depression, and somatization appear to be more prevalent in these dyspepsia patients than in those with organic issues. The incidence of gastric malignancy is low in this cohort.3,5 Dyspepsia occurring after an acute infection is referred to as postinfectious functional dyspepsia.

Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, mucosal immune dysfunction, altered gut microbiota, and disturbed central nervous system processing contribute in varying degrees to the pathophysiology of FD. There is evidence that luminal factors have the potential to trigger local neuronal excitability.6,7 Early life psychosocial factors may further influence illness behaviors, coping strategies, stress responses, and the intensity of symptoms perceived by the patient.8

Clues in the history and physical examination

Patients describe their discomfort using a variety of terms, including pain, gnawing, burning, gassiness, or queasiness. Although allergic reactions to food (swelling of lips and tongue with a rash) are rare in adults, food intolerances are common in patients with dyspepsia.9 Consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is a common cause of dyspepsia, even at over-the-counter strength, and may cause ulceration, gastrointestinal bleeding, and anemia. Narcotic and marijuana use and the anticholinergic effects of antidepressant medications are associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility, including gastroparesis.

Patients with FD often exhibit symptoms of other functional abdominal disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, functional heartburn, bloating, or chronic nausea, and may have been previously diagnosed with overlapping conditions suggestive of visceral hypersensitivity, including depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, migraine, and pelvic pain. During the patient’s office visit, be alert to any indication of an underlying psychological issue.

Continue to: The initial diagnostic challenge

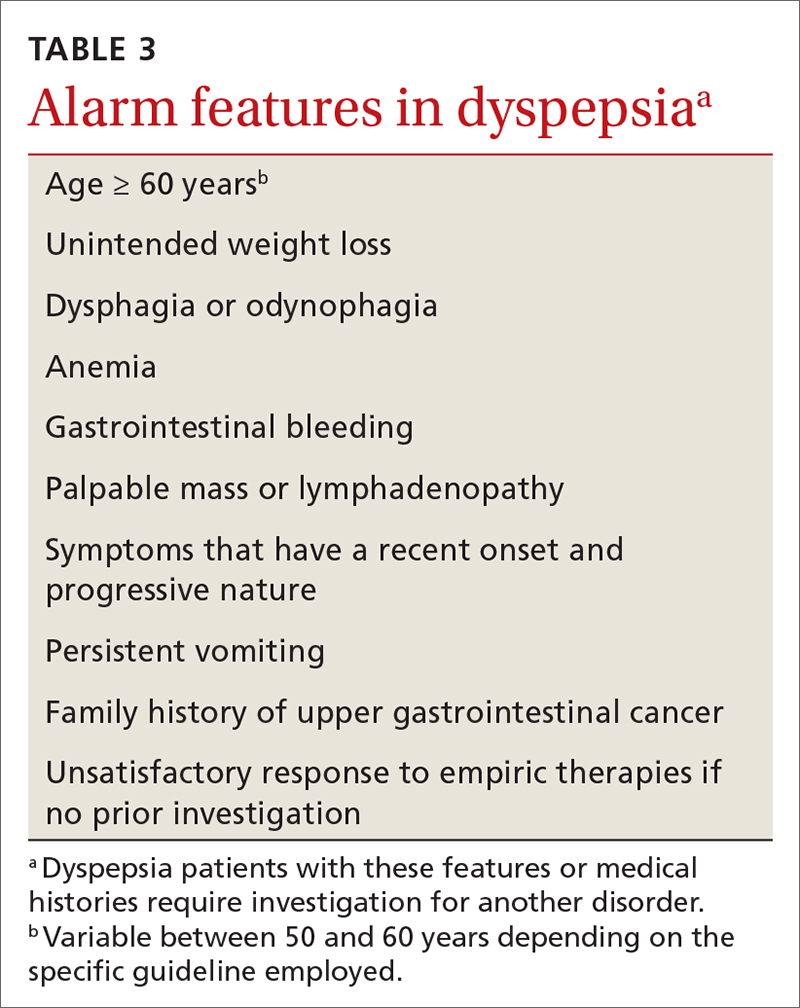

The initial diagnostic challenge is to identify those patients who may have a structural disorder requiring expedited and targeted investigation. Weight loss, night waking, and vomiting are unusual in the setting of either FD or Helicobacter pylori gastritis. These and other features of concern (TABLE 3) make a diagnosis of a functional disorder less likely and should prompt immediate consideration of abdominal imaging or endoscopic examination. Epigastric tenderness on palpation is common in patients with FD and is not necessarily predictive of structural pathology—unless accompanied by other findings of concern. Abdominal scars or a history of trauma may be suggestive of abdominal wall pain. Abdominal pain that remains unchanged or increases when the muscles of the abdominal wall are tensed (Carnett sign) suggests abdominal wall pain.

Initial testing and Tx assessments focus on H pylori

All 3 of the major US gastroenterology organizations recommend a stepwise approach in patients without alarm symptoms, generally beginning (in those < 60 years) by testing for H pylori with either the stool antigen or urea breath test (UBT)—and initiating appropriate treatment if results are positive.5,10 (The first step for those ≥ 60 years is discussed later.) Since the serum antibody test cannot differentiate between active and past infection, it is not recommended if other options are available.11 The stool antigen test is preferred; it is a cost-effective option used for both diagnosis and confirmation of H pylori eradication.

The UBT identifies active infection with a sensitivity and specificity of > 95%12 but is more labor intensive, employs an isotope, and is relatively expensive. Because proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth, and antibiotics may increase the false-negative rate for both the UBT and stool antigen test, we recommend that these medications be held for 2 to 4 weeks prior to testing.11 H2-receptor antagonists do not need to be restricted.

Treatment regimens containing clarithromycin have fallen into disfavor given the high rates of resistance that are now encountered. Fourteen-day regimens that can be used empirically (without susceptibility testing) are bismuth quadruple therapy (bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline, and PPI) or rifabutin triple therapy (rifabutin, amoxicillin, and PPI).13 To confirm eradication, perform repeat testing with either stool antigen or UBT no sooner than 4 weeks after completion of therapy. If the first treatment fails, try a second regimen using different antibiotics.14 Although the impact of H pylori eradication on dyspeptic symptoms is only modest, this strategy is recommended also to reduce the risk of peptic ulceration and gastric neoplasia.

Next-step testing and Tx considerations

Given the heterogeneity of presenting symptoms of dyspepsia, some clinicians may be hesitant to diagnose a functional disorder at the first visit, preferring instead to conduct a limited range of investigations in concert with initial medical management. In these circumstances it would be reasonable, in addition to testing for H pylori, to order a complete blood count (CBC) and to measure serum lipase and liver enzymes. Keep in mind that liver enzymes may not be elevated in uncomplicated biliary colic.

Continue to: Consider ultrasound imaging...

Consider ultrasound imaging if gallstones are a consideration. A computerized tomography scan may not exclude uncomplicated and noncalcified gallstones, but it is an excellent modality for detecting suspected retroperitoneal pathology. Consider working with a gastroenterologist if the patient exhibits alarm features.

Empiric PPI therapy. A trial of daily PPI use over 4 weeks is recommended for patients without H pylori and for those whose symptoms continue despite eradication of the bacterium. A Cochrane meta-analysis found that PPI therapy was more effective than placebo (31% vs 26%; risk ratio, 0.88; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11; 95% CI 0.82 to 0.94; P < .001).15 PPI therapy appears to be slightly more effective than treatment with H2-receptor antagonists. Both are proposed in the United Kingdom guideline.16 Both are generally safe and well tolerated but are not without potential adverse effects when used long term.

Dietary modification. Patients with dyspepsia commonly report that meals exacerbate symptoms. This is likely due to a combination of gastric distension and underlying visceral hypersensitivity rather than food composition.

There is no reliable “dyspepsia diet,” although a systematic review implicated wheat and high-fat foods as the 2 most common contributors to symptom onset.17 Recommended dietary modifications would be to consume smaller, more frequent meals and to eliminate recognized trigger foods. Patients with postprandial distress syndrome, a subset of FD, may want to consider reducing fat intake to help alleviate discomfort. If symptoms continue, evaluate for lactose intolerance. Also, consider a trial of a gluten-free diet. The low-FODMAP diet (restricting fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides, as well as polyols) has shown benefit in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and may be considered in those with intractable FD, given the overlap in physiology of the disorders.

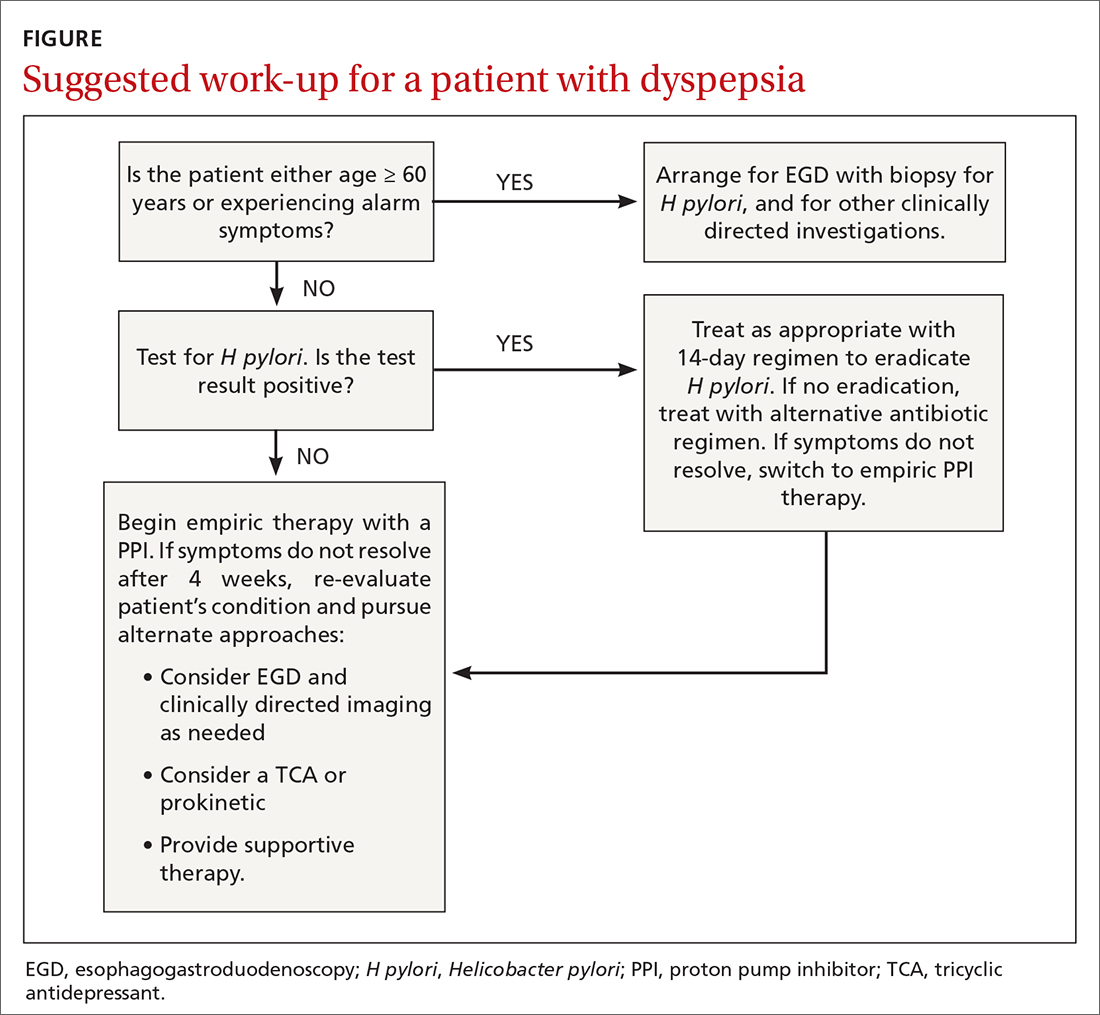

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The ACG has suggested that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) be performed as the first investigative step for patients ≥ 60 years, while testing for H pylori be considered as the first step in younger patients, even if alarm symptoms are present2 (FIGURE). This decision must be individualized, particularly in patients of Asian, Central or South American, or Caribbean descent, in whom the incidence of gastric cancer is higher with earlier onset.18

Continue to: Also consider EGD...

Also consider EGD for patients whose symptoms have not improved despite eradication of H pylori or an adequate trial of PPI therapy. While some guidelines do not require EGD in low-risk patients at this stage, other authorities would consider this step prudent, particularly when quality of life has been significantly impaired. An underlying organic cause, mainly erosive esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease, is found in 20% to 30% of patients with dyspepsia.5

Most patients without alarm features, with normal findings on upper endoscopy, who do not have H pylori gastritis, and whose symptoms continue despite a trial of PPI therapy, will have FD (FIGURE).2

Offer patients with functional dyspepsia supportive therapy

Neuromodulators

TCAs are superior to placebo in reducing dyspeptic symptoms with an NNT of 6 and are recommended for patients with ongoing symptoms despite PPI therapy or H pylori eradication.2 Begin with a low dose and increase as tolerated. It may take a few weeks for improvement to be seen. Exercise caution in the presence of cardiac arrhythmias.

Mirtazapine, 7.5 to 15 mg every night at bedtime, reduces fullness and bloating in postprandial distress syndrome and is useful for patients who have lost weight. It’s important to note that TCAs and mirtazapine both have the potential for QT prolongation, as well as depression and suicidality in younger patients.19 The anxiolytic buspirone, 10 mg before meals, augments fundic relaxation, improves overall symptom severity, and helps alleviate early satiety, postprandial fullness, and upper abdominal bloating.20

Prokinetics

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated significant benefit in symptom control in dyspeptic patients treated with prokinetics (NNT = 7).21 However, the benefit was predominantly due to cisapride, a drug that was withdrawn from the US market due to adverse effects. There are no clinical trials of metoclopramide or domperidone (not available in the United States) in FD. Nonetheless, the ACG has given a conditional recommendation, based on low-quality evidence, for the use of prokinetics in patients with FD not responding to PPI therapy, H pylori eradication, or TCA therapy.2

Continue to: A shortcoming of the established guidelines

A shortcoming of the established guidelines is that they do not provide guidance as to long-term management of those patients who respond to prescription medications. Our practice has been to continue medications for a minimum of 3 months, then begin a slow taper in order to establish the lowest efficacious dose. Some patients may relapse and require full dosage for a longer period of time.

Adjunctive therapies are worth considering

Complementary and alternative medicines. Products containing ginger, carraway oil, artichoke leaf extract, turmeric, and red pepper are readily available without prescription and have long been used with variable results for dyspepsia.22 The 9-herb combination STW-5 has demonstrated superiority over placebo in a number of studies and has a favorable safety profile.23 The recommended dose is 10 to 20 drops tid. The European manufacturer has recently modified the package insert noting rare cases of hepatotoxicity.24

A commercially available formulation (FDgard) containing L-menthol (a key component of peppermint oil) and caraway has been found to reduce the intensity of symptoms in patients with FD. Potential adverse effects include nausea, contact dermatitis, bronchospasm, and atrial fibrillation. Cayenne, a red pepper extract, is available over the counter for the benefit for epigastric pain and bloating. Begin with a 500-mg dose before breakfast and a 1000-mg dose before dinner, increasing to 2500 mg/d as tolerated. Cayenne preparations may trigger drug toxicities and are best avoided in patients taking antihypertensives, theophylline, or anticoagulants.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and hypnosis. These modalities are time consuming, are often expensive, are not always covered by insurance, and require significant motivation. A systematic review found no benefit.25 Subsequent studies summarized in the ACG guidelines2 reported benefit; however, a lack of blinding and significant heterogeneity among the groups detract from the quality of the data. It remains unclear whether these are effective strategies for FD, and therefore they cannot be recommended on a routine basis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Norman H. Gilinsky, MD, Division of Digestive Diseases, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0595; norman.gilinsky@ uc.edu

1. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049-1057.

2. Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988-1013.

3. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, et al. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:830-837.

4. Stanghellini V, Chan FKL, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392.

5. Shaukat A, Wang A, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:227-232.

6. Wauters L, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Novel concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2020;69:591-600.

7. Weinstock LB, Pace LA, Rezaie A, et al. Mast cell activation syndrome: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:965-982.

8. Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders. History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(16)00223-7/fulltext

9. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:728-736.

10. Talley NJ, AGA. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. 2005;129:1753-1755.

11. El-Serag HB, Kao JY, Kanwal F, et al. Houston Consensus Conference on testing for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:992-1002.

12. Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, et al. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1305-1314.

13. Howden CW, Graham DY. Recent developments pertaining to H. pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1-3.

14. Chey WD, Leontiadis G, Howden W, et al. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239.

15. Pinto-Sanchez MI, Yuan Y, Hassan A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors for functional dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011194.

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. [Clinical guideline] Accessed August 6, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552570/

17. Duncanson KR, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Food and functional dyspepsia: a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:390-407.

18. Lin JT. Screening of gastric cancer: who, when, and how. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:135-138.

19. Spielmans GI, Spence-Sing T, Parry P. Duty to warn: antidepressant black box suicidality warning is empirically justified. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1-18.

20. Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, et al. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1239-1245.

21. Pittayanon R, Yuan Y, Bollegala NP, et al. Prokinetics for functional dyspepsia: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:233-243.

22. Deutsch JK, Levitt J, Hass DJ. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:350-364.

23. Malfertheiner P. STW 5 (iberogast) therapy in gastrointestinal functional disorders. Dig Dis. 2017;35:25-29.

24. Sáez-González E, Conde I, Díaz-Jaime FC, et al. Iberogast-induced severe hepatotoxicity leading to liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1364-1365.

25. Soo S, Forman D, Delaney B, et al. A systematic review of psychological therapies for nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1817-1822.

The global prevalence of dyspepsia is approximately 20%,1 and it is often associated with other comorbidities and overlapping gastrointestinal complaints. The effects on the patient’s quality of life, including societal impacts, are considerable. Symptoms and their response to treatment are highly variable, necessitating individualized management. While some patients’ symptoms may be refractory to standard medical treatment initially, evidence suggests that the strategies summarized in our guidance here—including the use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), prokinetics, and adjunctive therapies—may alleviate symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

What dyspepsia is—and what it isn’t

Dyspepsia is a poorly characterized disorder often associated with nausea, heartburn, early satiety, and bloating. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) now advocates using a clinically relevant definition of dyspepsia as “predominant epigastric pain lasting at least a month” as long as epigastric pain is the patient's primary complaint.2 Causes of dyspepsia are listed in TABLE 1.

Heartburn, a burning sensation in the chest, is not a dyspeptic symptom but the 2 may often coexist. In general, dyspepsia does not have a colicky or postural component. Symptoms that are relieved by evacuation of feces or gas generally should not be considered a part of dyspepsia.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a subset for which no structural pathology has been identified, accounting for up to 70% of all patients with dyspepsia.3 The Rome Foundation, in its recent update (Rome IV), has highlighted 4 key symptoms and 2 proposed subtypes (TABLE 2).4 The comorbidities of anxiety, depression, and somatization appear to be more prevalent in these dyspepsia patients than in those with organic issues. The incidence of gastric malignancy is low in this cohort.3,5 Dyspepsia occurring after an acute infection is referred to as postinfectious functional dyspepsia.

Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, mucosal immune dysfunction, altered gut microbiota, and disturbed central nervous system processing contribute in varying degrees to the pathophysiology of FD. There is evidence that luminal factors have the potential to trigger local neuronal excitability.6,7 Early life psychosocial factors may further influence illness behaviors, coping strategies, stress responses, and the intensity of symptoms perceived by the patient.8

Clues in the history and physical examination

Patients describe their discomfort using a variety of terms, including pain, gnawing, burning, gassiness, or queasiness. Although allergic reactions to food (swelling of lips and tongue with a rash) are rare in adults, food intolerances are common in patients with dyspepsia.9 Consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is a common cause of dyspepsia, even at over-the-counter strength, and may cause ulceration, gastrointestinal bleeding, and anemia. Narcotic and marijuana use and the anticholinergic effects of antidepressant medications are associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility, including gastroparesis.

Patients with FD often exhibit symptoms of other functional abdominal disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, functional heartburn, bloating, or chronic nausea, and may have been previously diagnosed with overlapping conditions suggestive of visceral hypersensitivity, including depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, migraine, and pelvic pain. During the patient’s office visit, be alert to any indication of an underlying psychological issue.

Continue to: The initial diagnostic challenge

The initial diagnostic challenge is to identify those patients who may have a structural disorder requiring expedited and targeted investigation. Weight loss, night waking, and vomiting are unusual in the setting of either FD or Helicobacter pylori gastritis. These and other features of concern (TABLE 3) make a diagnosis of a functional disorder less likely and should prompt immediate consideration of abdominal imaging or endoscopic examination. Epigastric tenderness on palpation is common in patients with FD and is not necessarily predictive of structural pathology—unless accompanied by other findings of concern. Abdominal scars or a history of trauma may be suggestive of abdominal wall pain. Abdominal pain that remains unchanged or increases when the muscles of the abdominal wall are tensed (Carnett sign) suggests abdominal wall pain.

Initial testing and Tx assessments focus on H pylori

All 3 of the major US gastroenterology organizations recommend a stepwise approach in patients without alarm symptoms, generally beginning (in those < 60 years) by testing for H pylori with either the stool antigen or urea breath test (UBT)—and initiating appropriate treatment if results are positive.5,10 (The first step for those ≥ 60 years is discussed later.) Since the serum antibody test cannot differentiate between active and past infection, it is not recommended if other options are available.11 The stool antigen test is preferred; it is a cost-effective option used for both diagnosis and confirmation of H pylori eradication.

The UBT identifies active infection with a sensitivity and specificity of > 95%12 but is more labor intensive, employs an isotope, and is relatively expensive. Because proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth, and antibiotics may increase the false-negative rate for both the UBT and stool antigen test, we recommend that these medications be held for 2 to 4 weeks prior to testing.11 H2-receptor antagonists do not need to be restricted.

Treatment regimens containing clarithromycin have fallen into disfavor given the high rates of resistance that are now encountered. Fourteen-day regimens that can be used empirically (without susceptibility testing) are bismuth quadruple therapy (bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline, and PPI) or rifabutin triple therapy (rifabutin, amoxicillin, and PPI).13 To confirm eradication, perform repeat testing with either stool antigen or UBT no sooner than 4 weeks after completion of therapy. If the first treatment fails, try a second regimen using different antibiotics.14 Although the impact of H pylori eradication on dyspeptic symptoms is only modest, this strategy is recommended also to reduce the risk of peptic ulceration and gastric neoplasia.

Next-step testing and Tx considerations

Given the heterogeneity of presenting symptoms of dyspepsia, some clinicians may be hesitant to diagnose a functional disorder at the first visit, preferring instead to conduct a limited range of investigations in concert with initial medical management. In these circumstances it would be reasonable, in addition to testing for H pylori, to order a complete blood count (CBC) and to measure serum lipase and liver enzymes. Keep in mind that liver enzymes may not be elevated in uncomplicated biliary colic.

Continue to: Consider ultrasound imaging...

Consider ultrasound imaging if gallstones are a consideration. A computerized tomography scan may not exclude uncomplicated and noncalcified gallstones, but it is an excellent modality for detecting suspected retroperitoneal pathology. Consider working with a gastroenterologist if the patient exhibits alarm features.

Empiric PPI therapy. A trial of daily PPI use over 4 weeks is recommended for patients without H pylori and for those whose symptoms continue despite eradication of the bacterium. A Cochrane meta-analysis found that PPI therapy was more effective than placebo (31% vs 26%; risk ratio, 0.88; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11; 95% CI 0.82 to 0.94; P < .001).15 PPI therapy appears to be slightly more effective than treatment with H2-receptor antagonists. Both are proposed in the United Kingdom guideline.16 Both are generally safe and well tolerated but are not without potential adverse effects when used long term.

Dietary modification. Patients with dyspepsia commonly report that meals exacerbate symptoms. This is likely due to a combination of gastric distension and underlying visceral hypersensitivity rather than food composition.

There is no reliable “dyspepsia diet,” although a systematic review implicated wheat and high-fat foods as the 2 most common contributors to symptom onset.17 Recommended dietary modifications would be to consume smaller, more frequent meals and to eliminate recognized trigger foods. Patients with postprandial distress syndrome, a subset of FD, may want to consider reducing fat intake to help alleviate discomfort. If symptoms continue, evaluate for lactose intolerance. Also, consider a trial of a gluten-free diet. The low-FODMAP diet (restricting fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides, as well as polyols) has shown benefit in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and may be considered in those with intractable FD, given the overlap in physiology of the disorders.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The ACG has suggested that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) be performed as the first investigative step for patients ≥ 60 years, while testing for H pylori be considered as the first step in younger patients, even if alarm symptoms are present2 (FIGURE). This decision must be individualized, particularly in patients of Asian, Central or South American, or Caribbean descent, in whom the incidence of gastric cancer is higher with earlier onset.18

Continue to: Also consider EGD...

Also consider EGD for patients whose symptoms have not improved despite eradication of H pylori or an adequate trial of PPI therapy. While some guidelines do not require EGD in low-risk patients at this stage, other authorities would consider this step prudent, particularly when quality of life has been significantly impaired. An underlying organic cause, mainly erosive esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease, is found in 20% to 30% of patients with dyspepsia.5

Most patients without alarm features, with normal findings on upper endoscopy, who do not have H pylori gastritis, and whose symptoms continue despite a trial of PPI therapy, will have FD (FIGURE).2

Offer patients with functional dyspepsia supportive therapy

Neuromodulators

TCAs are superior to placebo in reducing dyspeptic symptoms with an NNT of 6 and are recommended for patients with ongoing symptoms despite PPI therapy or H pylori eradication.2 Begin with a low dose and increase as tolerated. It may take a few weeks for improvement to be seen. Exercise caution in the presence of cardiac arrhythmias.

Mirtazapine, 7.5 to 15 mg every night at bedtime, reduces fullness and bloating in postprandial distress syndrome and is useful for patients who have lost weight. It’s important to note that TCAs and mirtazapine both have the potential for QT prolongation, as well as depression and suicidality in younger patients.19 The anxiolytic buspirone, 10 mg before meals, augments fundic relaxation, improves overall symptom severity, and helps alleviate early satiety, postprandial fullness, and upper abdominal bloating.20

Prokinetics

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated significant benefit in symptom control in dyspeptic patients treated with prokinetics (NNT = 7).21 However, the benefit was predominantly due to cisapride, a drug that was withdrawn from the US market due to adverse effects. There are no clinical trials of metoclopramide or domperidone (not available in the United States) in FD. Nonetheless, the ACG has given a conditional recommendation, based on low-quality evidence, for the use of prokinetics in patients with FD not responding to PPI therapy, H pylori eradication, or TCA therapy.2

Continue to: A shortcoming of the established guidelines

A shortcoming of the established guidelines is that they do not provide guidance as to long-term management of those patients who respond to prescription medications. Our practice has been to continue medications for a minimum of 3 months, then begin a slow taper in order to establish the lowest efficacious dose. Some patients may relapse and require full dosage for a longer period of time.

Adjunctive therapies are worth considering

Complementary and alternative medicines. Products containing ginger, carraway oil, artichoke leaf extract, turmeric, and red pepper are readily available without prescription and have long been used with variable results for dyspepsia.22 The 9-herb combination STW-5 has demonstrated superiority over placebo in a number of studies and has a favorable safety profile.23 The recommended dose is 10 to 20 drops tid. The European manufacturer has recently modified the package insert noting rare cases of hepatotoxicity.24

A commercially available formulation (FDgard) containing L-menthol (a key component of peppermint oil) and caraway has been found to reduce the intensity of symptoms in patients with FD. Potential adverse effects include nausea, contact dermatitis, bronchospasm, and atrial fibrillation. Cayenne, a red pepper extract, is available over the counter for the benefit for epigastric pain and bloating. Begin with a 500-mg dose before breakfast and a 1000-mg dose before dinner, increasing to 2500 mg/d as tolerated. Cayenne preparations may trigger drug toxicities and are best avoided in patients taking antihypertensives, theophylline, or anticoagulants.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and hypnosis. These modalities are time consuming, are often expensive, are not always covered by insurance, and require significant motivation. A systematic review found no benefit.25 Subsequent studies summarized in the ACG guidelines2 reported benefit; however, a lack of blinding and significant heterogeneity among the groups detract from the quality of the data. It remains unclear whether these are effective strategies for FD, and therefore they cannot be recommended on a routine basis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Norman H. Gilinsky, MD, Division of Digestive Diseases, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0595; norman.gilinsky@ uc.edu

The global prevalence of dyspepsia is approximately 20%,1 and it is often associated with other comorbidities and overlapping gastrointestinal complaints. The effects on the patient’s quality of life, including societal impacts, are considerable. Symptoms and their response to treatment are highly variable, necessitating individualized management. While some patients’ symptoms may be refractory to standard medical treatment initially, evidence suggests that the strategies summarized in our guidance here—including the use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), prokinetics, and adjunctive therapies—may alleviate symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

What dyspepsia is—and what it isn’t

Dyspepsia is a poorly characterized disorder often associated with nausea, heartburn, early satiety, and bloating. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) now advocates using a clinically relevant definition of dyspepsia as “predominant epigastric pain lasting at least a month” as long as epigastric pain is the patient's primary complaint.2 Causes of dyspepsia are listed in TABLE 1.

Heartburn, a burning sensation in the chest, is not a dyspeptic symptom but the 2 may often coexist. In general, dyspepsia does not have a colicky or postural component. Symptoms that are relieved by evacuation of feces or gas generally should not be considered a part of dyspepsia.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a subset for which no structural pathology has been identified, accounting for up to 70% of all patients with dyspepsia.3 The Rome Foundation, in its recent update (Rome IV), has highlighted 4 key symptoms and 2 proposed subtypes (TABLE 2).4 The comorbidities of anxiety, depression, and somatization appear to be more prevalent in these dyspepsia patients than in those with organic issues. The incidence of gastric malignancy is low in this cohort.3,5 Dyspepsia occurring after an acute infection is referred to as postinfectious functional dyspepsia.

Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, mucosal immune dysfunction, altered gut microbiota, and disturbed central nervous system processing contribute in varying degrees to the pathophysiology of FD. There is evidence that luminal factors have the potential to trigger local neuronal excitability.6,7 Early life psychosocial factors may further influence illness behaviors, coping strategies, stress responses, and the intensity of symptoms perceived by the patient.8

Clues in the history and physical examination

Patients describe their discomfort using a variety of terms, including pain, gnawing, burning, gassiness, or queasiness. Although allergic reactions to food (swelling of lips and tongue with a rash) are rare in adults, food intolerances are common in patients with dyspepsia.9 Consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is a common cause of dyspepsia, even at over-the-counter strength, and may cause ulceration, gastrointestinal bleeding, and anemia. Narcotic and marijuana use and the anticholinergic effects of antidepressant medications are associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility, including gastroparesis.

Patients with FD often exhibit symptoms of other functional abdominal disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, functional heartburn, bloating, or chronic nausea, and may have been previously diagnosed with overlapping conditions suggestive of visceral hypersensitivity, including depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, migraine, and pelvic pain. During the patient’s office visit, be alert to any indication of an underlying psychological issue.

Continue to: The initial diagnostic challenge

The initial diagnostic challenge is to identify those patients who may have a structural disorder requiring expedited and targeted investigation. Weight loss, night waking, and vomiting are unusual in the setting of either FD or Helicobacter pylori gastritis. These and other features of concern (TABLE 3) make a diagnosis of a functional disorder less likely and should prompt immediate consideration of abdominal imaging or endoscopic examination. Epigastric tenderness on palpation is common in patients with FD and is not necessarily predictive of structural pathology—unless accompanied by other findings of concern. Abdominal scars or a history of trauma may be suggestive of abdominal wall pain. Abdominal pain that remains unchanged or increases when the muscles of the abdominal wall are tensed (Carnett sign) suggests abdominal wall pain.

Initial testing and Tx assessments focus on H pylori

All 3 of the major US gastroenterology organizations recommend a stepwise approach in patients without alarm symptoms, generally beginning (in those < 60 years) by testing for H pylori with either the stool antigen or urea breath test (UBT)—and initiating appropriate treatment if results are positive.5,10 (The first step for those ≥ 60 years is discussed later.) Since the serum antibody test cannot differentiate between active and past infection, it is not recommended if other options are available.11 The stool antigen test is preferred; it is a cost-effective option used for both diagnosis and confirmation of H pylori eradication.

The UBT identifies active infection with a sensitivity and specificity of > 95%12 but is more labor intensive, employs an isotope, and is relatively expensive. Because proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth, and antibiotics may increase the false-negative rate for both the UBT and stool antigen test, we recommend that these medications be held for 2 to 4 weeks prior to testing.11 H2-receptor antagonists do not need to be restricted.

Treatment regimens containing clarithromycin have fallen into disfavor given the high rates of resistance that are now encountered. Fourteen-day regimens that can be used empirically (without susceptibility testing) are bismuth quadruple therapy (bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline, and PPI) or rifabutin triple therapy (rifabutin, amoxicillin, and PPI).13 To confirm eradication, perform repeat testing with either stool antigen or UBT no sooner than 4 weeks after completion of therapy. If the first treatment fails, try a second regimen using different antibiotics.14 Although the impact of H pylori eradication on dyspeptic symptoms is only modest, this strategy is recommended also to reduce the risk of peptic ulceration and gastric neoplasia.

Next-step testing and Tx considerations

Given the heterogeneity of presenting symptoms of dyspepsia, some clinicians may be hesitant to diagnose a functional disorder at the first visit, preferring instead to conduct a limited range of investigations in concert with initial medical management. In these circumstances it would be reasonable, in addition to testing for H pylori, to order a complete blood count (CBC) and to measure serum lipase and liver enzymes. Keep in mind that liver enzymes may not be elevated in uncomplicated biliary colic.

Continue to: Consider ultrasound imaging...

Consider ultrasound imaging if gallstones are a consideration. A computerized tomography scan may not exclude uncomplicated and noncalcified gallstones, but it is an excellent modality for detecting suspected retroperitoneal pathology. Consider working with a gastroenterologist if the patient exhibits alarm features.

Empiric PPI therapy. A trial of daily PPI use over 4 weeks is recommended for patients without H pylori and for those whose symptoms continue despite eradication of the bacterium. A Cochrane meta-analysis found that PPI therapy was more effective than placebo (31% vs 26%; risk ratio, 0.88; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11; 95% CI 0.82 to 0.94; P < .001).15 PPI therapy appears to be slightly more effective than treatment with H2-receptor antagonists. Both are proposed in the United Kingdom guideline.16 Both are generally safe and well tolerated but are not without potential adverse effects when used long term.

Dietary modification. Patients with dyspepsia commonly report that meals exacerbate symptoms. This is likely due to a combination of gastric distension and underlying visceral hypersensitivity rather than food composition.

There is no reliable “dyspepsia diet,” although a systematic review implicated wheat and high-fat foods as the 2 most common contributors to symptom onset.17 Recommended dietary modifications would be to consume smaller, more frequent meals and to eliminate recognized trigger foods. Patients with postprandial distress syndrome, a subset of FD, may want to consider reducing fat intake to help alleviate discomfort. If symptoms continue, evaluate for lactose intolerance. Also, consider a trial of a gluten-free diet. The low-FODMAP diet (restricting fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides, as well as polyols) has shown benefit in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and may be considered in those with intractable FD, given the overlap in physiology of the disorders.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The ACG has suggested that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) be performed as the first investigative step for patients ≥ 60 years, while testing for H pylori be considered as the first step in younger patients, even if alarm symptoms are present2 (FIGURE). This decision must be individualized, particularly in patients of Asian, Central or South American, or Caribbean descent, in whom the incidence of gastric cancer is higher with earlier onset.18

Continue to: Also consider EGD...

Also consider EGD for patients whose symptoms have not improved despite eradication of H pylori or an adequate trial of PPI therapy. While some guidelines do not require EGD in low-risk patients at this stage, other authorities would consider this step prudent, particularly when quality of life has been significantly impaired. An underlying organic cause, mainly erosive esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease, is found in 20% to 30% of patients with dyspepsia.5

Most patients without alarm features, with normal findings on upper endoscopy, who do not have H pylori gastritis, and whose symptoms continue despite a trial of PPI therapy, will have FD (FIGURE).2

Offer patients with functional dyspepsia supportive therapy

Neuromodulators

TCAs are superior to placebo in reducing dyspeptic symptoms with an NNT of 6 and are recommended for patients with ongoing symptoms despite PPI therapy or H pylori eradication.2 Begin with a low dose and increase as tolerated. It may take a few weeks for improvement to be seen. Exercise caution in the presence of cardiac arrhythmias.

Mirtazapine, 7.5 to 15 mg every night at bedtime, reduces fullness and bloating in postprandial distress syndrome and is useful for patients who have lost weight. It’s important to note that TCAs and mirtazapine both have the potential for QT prolongation, as well as depression and suicidality in younger patients.19 The anxiolytic buspirone, 10 mg before meals, augments fundic relaxation, improves overall symptom severity, and helps alleviate early satiety, postprandial fullness, and upper abdominal bloating.20

Prokinetics

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated significant benefit in symptom control in dyspeptic patients treated with prokinetics (NNT = 7).21 However, the benefit was predominantly due to cisapride, a drug that was withdrawn from the US market due to adverse effects. There are no clinical trials of metoclopramide or domperidone (not available in the United States) in FD. Nonetheless, the ACG has given a conditional recommendation, based on low-quality evidence, for the use of prokinetics in patients with FD not responding to PPI therapy, H pylori eradication, or TCA therapy.2

Continue to: A shortcoming of the established guidelines

A shortcoming of the established guidelines is that they do not provide guidance as to long-term management of those patients who respond to prescription medications. Our practice has been to continue medications for a minimum of 3 months, then begin a slow taper in order to establish the lowest efficacious dose. Some patients may relapse and require full dosage for a longer period of time.

Adjunctive therapies are worth considering

Complementary and alternative medicines. Products containing ginger, carraway oil, artichoke leaf extract, turmeric, and red pepper are readily available without prescription and have long been used with variable results for dyspepsia.22 The 9-herb combination STW-5 has demonstrated superiority over placebo in a number of studies and has a favorable safety profile.23 The recommended dose is 10 to 20 drops tid. The European manufacturer has recently modified the package insert noting rare cases of hepatotoxicity.24

A commercially available formulation (FDgard) containing L-menthol (a key component of peppermint oil) and caraway has been found to reduce the intensity of symptoms in patients with FD. Potential adverse effects include nausea, contact dermatitis, bronchospasm, and atrial fibrillation. Cayenne, a red pepper extract, is available over the counter for the benefit for epigastric pain and bloating. Begin with a 500-mg dose before breakfast and a 1000-mg dose before dinner, increasing to 2500 mg/d as tolerated. Cayenne preparations may trigger drug toxicities and are best avoided in patients taking antihypertensives, theophylline, or anticoagulants.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and hypnosis. These modalities are time consuming, are often expensive, are not always covered by insurance, and require significant motivation. A systematic review found no benefit.25 Subsequent studies summarized in the ACG guidelines2 reported benefit; however, a lack of blinding and significant heterogeneity among the groups detract from the quality of the data. It remains unclear whether these are effective strategies for FD, and therefore they cannot be recommended on a routine basis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Norman H. Gilinsky, MD, Division of Digestive Diseases, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0595; norman.gilinsky@ uc.edu

1. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049-1057.

2. Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988-1013.

3. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, et al. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:830-837.

4. Stanghellini V, Chan FKL, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392.

5. Shaukat A, Wang A, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:227-232.

6. Wauters L, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Novel concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2020;69:591-600.

7. Weinstock LB, Pace LA, Rezaie A, et al. Mast cell activation syndrome: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:965-982.

8. Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders. History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(16)00223-7/fulltext

9. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:728-736.

10. Talley NJ, AGA. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. 2005;129:1753-1755.

11. El-Serag HB, Kao JY, Kanwal F, et al. Houston Consensus Conference on testing for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:992-1002.

12. Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, et al. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1305-1314.

13. Howden CW, Graham DY. Recent developments pertaining to H. pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1-3.

14. Chey WD, Leontiadis G, Howden W, et al. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239.

15. Pinto-Sanchez MI, Yuan Y, Hassan A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors for functional dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011194.

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. [Clinical guideline] Accessed August 6, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552570/

17. Duncanson KR, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Food and functional dyspepsia: a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:390-407.

18. Lin JT. Screening of gastric cancer: who, when, and how. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:135-138.

19. Spielmans GI, Spence-Sing T, Parry P. Duty to warn: antidepressant black box suicidality warning is empirically justified. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1-18.

20. Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, et al. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1239-1245.

21. Pittayanon R, Yuan Y, Bollegala NP, et al. Prokinetics for functional dyspepsia: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:233-243.

22. Deutsch JK, Levitt J, Hass DJ. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:350-364.

23. Malfertheiner P. STW 5 (iberogast) therapy in gastrointestinal functional disorders. Dig Dis. 2017;35:25-29.

24. Sáez-González E, Conde I, Díaz-Jaime FC, et al. Iberogast-induced severe hepatotoxicity leading to liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1364-1365.

25. Soo S, Forman D, Delaney B, et al. A systematic review of psychological therapies for nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1817-1822.

1. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049-1057.

2. Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988-1013.

3. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, et al. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:830-837.

4. Stanghellini V, Chan FKL, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392.

5. Shaukat A, Wang A, Acosta RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:227-232.

6. Wauters L, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Novel concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2020;69:591-600.

7. Weinstock LB, Pace LA, Rezaie A, et al. Mast cell activation syndrome: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:965-982.

8. Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders. History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(16)00223-7/fulltext

9. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:728-736.

10. Talley NJ, AGA. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterol. 2005;129:1753-1755.

11. El-Serag HB, Kao JY, Kanwal F, et al. Houston Consensus Conference on testing for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:992-1002.

12. Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I, Alhajiahmed A, et al. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1305-1314.

13. Howden CW, Graham DY. Recent developments pertaining to H. pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1-3.

14. Chey WD, Leontiadis G, Howden W, et al. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239.

15. Pinto-Sanchez MI, Yuan Y, Hassan A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors for functional dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011194.

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. [Clinical guideline] Accessed August 6, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552570/

17. Duncanson KR, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Food and functional dyspepsia: a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:390-407.

18. Lin JT. Screening of gastric cancer: who, when, and how. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:135-138.

19. Spielmans GI, Spence-Sing T, Parry P. Duty to warn: antidepressant black box suicidality warning is empirically justified. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1-18.

20. Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, et al. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1239-1245.

21. Pittayanon R, Yuan Y, Bollegala NP, et al. Prokinetics for functional dyspepsia: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:233-243.

22. Deutsch JK, Levitt J, Hass DJ. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:350-364.

23. Malfertheiner P. STW 5 (iberogast) therapy in gastrointestinal functional disorders. Dig Dis. 2017;35:25-29.

24. Sáez-González E, Conde I, Díaz-Jaime FC, et al. Iberogast-induced severe hepatotoxicity leading to liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1364-1365.

25. Soo S, Forman D, Delaney B, et al. A systematic review of psychological therapies for nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1817-1822.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Test for Helicobacter pylori in patients who are < 60 years of age or who have no alarm symptoms. If results are negative, consider a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy. C

› Arrange for esophagogastroduodenoscopy in individuals ≥ 60 years of age and all patients with alarm symptoms, to identify or rule out a structural cause. C

› Consider a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia if the work-up is negative. Supportive therapy, including the use of tricyclic antidepressants, prokinetics, and a holistic approach to lifestyle changes in select patients have shown encouraging results. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Microbiome startups promise to improve your gut health, but is the science solid?

The gym owner in Sacramento, had always consumed large quantities of leafy greens. But the results from the test – which sequenced and analyzed the microbes in a pea-sized stool sample – recommended he steer clear of spinach, kale, and broccoli.

“Things I’ve been eating for the better part of 30 years,” said Mr. Jordan, 31. “And it worked.” Soon, his mild indigestion subsided. He recommended the product to his girlfriend.

She took the test in late February, when the company – which sells its “Gut Intelligence” test for $129 and a more extensive “Health Intelligence” test, which requires a blood sample, for $199 – began experiencing hiccups. Viome had promised results within 4 weeks once the sample arrived at a testing facility, but Mr. Jordan said his girlfriend has been waiting more than 5 months and has submitted fresh blood and stool samples – twice.

Other Viome customers have flocked to social media to complain about similar problems: stool samples lost in the mail, months-long waits with no communication from the company, samples being rejected because of shipping or lab-processing snafus. (I, too, have a stool sample lost in transit, which I mailed after a first vial was rejected because it “leaked.”) The company’s CEO, Naveen Jain, took to Facebook to apologize in late July.

Viome’s troubles provide a cautionary tale for consumers in the wild west of microbiome startups, which have been alternately hailed for health breakthroughs and indicted for fraud.

The nascent industry offers individualized diet regimens based on analyzing gut bacteria – collectively known as the gut microbiome. Consumers pay hundreds of dollars for tests not covered by insurance, hoping to get answers to health problems ranging from irritable bowel syndrome to obesity.

Venture capitalists pumped $1 billion into these kinds of startups from 2015 to 2020, according to Crunchbase, buoyed by promising research and consumers’ embrace of at-home testing. PitchBook has identified more than a dozen direct-to-consumer gut health providers.

But not all the startups are equal. Some are supported by peer-reviewed studies. Others are peddling murky science – and not just because poop samples are getting lost in the mail.

“A lot of companies are interested in the space, but they don’t have the research to show that it’s actually working,” said Christopher Lynch, acting director of the National Institutes of Health Office of Nutrition Research. “And the research is really expensive.”

With nearly $160 million in government funding, the NIH Common Fund’s Nutrition for Precision Health research program, expected to launch by early 2022, seeks to enroll 1 million people to study the interactions among diet, the microbiome, genes, metabolism and other factors.

The gut microbiome is a complex community of trillions of bacteria. Research over the past 15 years has determined that these microbes, both good and bad, are an integral part of human biology, and that altering a person’s gut microbes can fundamentally change their metabolism, immune function – and, potentially, cure diseases, explained Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, a microbiology and immunology associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Metagenomic sequencing, which identifies the unique set of bugs in someone’s gut (similar to what 23andMe does with its saliva test), has also improved dramatically, making the process cheaper for companies to reproduce.

“It’s seen as one of the exciting areas of precision health,” said Dr. Sonnenburg, who recently coauthored a study that found a fermented food diet increases microbiome diversity – which is considered positive – and reduces markers of inflammation. That includes foods like yogurt, kefir, and kimchi.

“The difficulty for the consumer is to differentiate which of these companies is based on solid science versus overreaching the current limits of the field,” he added via email. “And for those companies based on solid science, what are the limits of what they should be recommending?”

San Francisco–based uBiome, founded in 2012, was one of the first to offer fecal sample testing.

But as uBiome began marketing its tests as “clinical” – and seeking reimbursement from insurers for up to nearly $3,000 – its business tactics came under scrutiny. The company was raided by the FBI and later filed for bankruptcy. Earlier this year, its cofounders were indicted for defrauding insurers into paying for tests that “were not validated and not medically necessary” in order to please investors, the Department of Justice alleges.

But for Tim Spector, a professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London and cofounder of the startup Zoe, being associated with uBiome is insulting.

Zoe has spent more than 2 years conducting trials, which have included dietary assessments, standardized meals, testing glycemic responses and gut microbiome profiling on thousands of participants. In January, the findings were published in Nature Medicine.

The company offers a $354 test that requires a stool sample, a completed questionnaire, and then a blood sample after eating muffins designed to test blood fat and sugar levels. Customers can also opt in to a 2-week, continuous glucose monitoring test.

The results are run through the company’s algorithm to create a customized library of foods and meals – and how customers are likely to respond to those foods.

DayTwo, a Walnut Creek, Calif., company that recently raised $37 million to expand its precision nutrition program, focuses on people with prediabetes or diabetes. It sells to large employers – and, soon, to health insurance plans – rather than directly to consumers, charging “a few thousand dollars” per person, said Jan Berger, MD, chief clinical strategist.