User login

Simplifying or Switching Antiretroviral Therapy in Treatment-Experienced Adults Living With HIV

A 57-year-old man living with HIV has been followed at a local infectious disease clinic for more than 15 years. He acquired HIV disease through heterosexual contact. He lives alone and works at a convenience store; he has not been sexually active for the past 5 years. He smokes 10 cigarettes a day, but does not drink alcohol or use illicit drugs. He had been on coformulated emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and coformulated lopinavir/ritonavir, which he had taken conscientiously, since May 2008, without noticing any adverse reactions from this regimen. His HIV viral load had been undetectable, and his CD4 count had hovered between 600 and 700 cells/µL. Although he was on atorvastatin for dyslipidemia, his fasting lipid profile, performed in 2018, revealed a total cholesterol level of 200 mg/dL;triglyceride, 247 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 43 mg/dL; and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 132 mg/dL. In April 2019, his HIV regimen was switched to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Blood tests performed in December 2019 revealed undetectable HIV viral load; an increased CD4 count to 849 cell/µL; total cholesterol, 140 mg/dL; triglyceride, 115 mg/dL; HDL, 60 mg/dL; and LDL, 90 mg/dL.

SIMPLIFYING ART

Virologically Suppressed Patients Without Drug-Resistant Virus

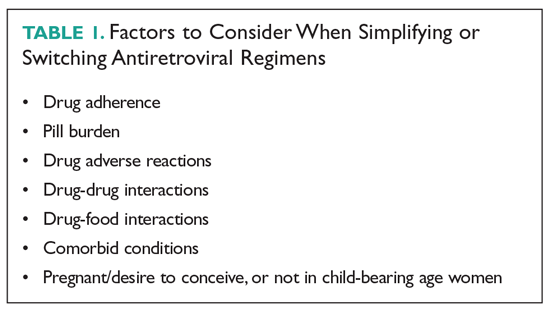

Treatment adherence is of paramount importance to ensure treatment success. Patients with a viral load that is undetectable or nearly undetectable without drug resistance could be taking ART regimens consisting of more than 1 pill and/or that require more than once-daily dosing. Decreasing pill burden or dosing frequency can help to improve adherence to treatment. In addition, older-generation ART agents are usually more toxic and less potent than newer-generation agents, so another important objective of switching older drugs to newer drugs is to decrease adverse reactions and improve virologic suppression. Selection of an ART regimen should be guided by the results of resistance testing (genotyping and phenotyping tests) and previous treatment history. After switching a patient’s ART regimen, plasma HIV viral load and CD4 count should be closely monitored.2 The following 3-drug, single-tablet, once-daily ART regimens can be used in patients who are virologically stable (ordered chronologically by FDA approval dates).

Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla)

Coformulated efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF was the first single-tablet, once-daily, fixed-dose combination approved by the FDA (July 2006). Approval was based on a 48- week clinical trial involving 244 adults with HIV infection that showed that 80% of participants achieved a marked reduction in HIV viral load and a significant increase in CD4 cell count.3 Of the 3 components, efavirenz has unique central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects that could reduce adherence. Patients who were started on this fixed-dose combination commonly reported dizziness, headache, nightmare, insomnia, and impaired concentration.4 However, the CNS side effects resolved within the first 4 weeks of therapy, and less than 5% of patients quit taking the drug. Primate studies showed efavirenz is teratogenic, but studies in pregnant women did not find efavirenz to be more teratogenic than other ART agents.5

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TDF (Complera)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TDF was approved based on data from two 48-week, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials (ECHO and THRIVE) that evaluated the safety and efficacy of rilpivirine compared to efavirenz among treatment-naive adults with HIV infection.7,8 Rilpivirine is well tolerated and causes fewer CNS symptoms compared to efavirenz. The main caveat for rilpivirine is drug-drug interactions. It should not be coadministered with CYP inducers, such as rifampin, phenytoin, or St. John’s wort, as coadministration can cause subtherapeutic blood levels of rilpivirine. Because increased levels of rilpivirine can prolong QTc on electrocardiogram (ECG), an ECG should be obtained before starting an ART regimen that contains rilpivirine, especially in the presence of CYP 3A4 inhibitors.9

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild)

This coformulation was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled trials, Study 102 and Study 103, in treatment-naive patients with HIV (n = 1408). In Study 102, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla).10 In Study 103, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or atazanavir + ritonavir + emtricitabine/TDF. In both studies, the primary endpoint was virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) at 48 weeks, and elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF was noninferior compared to the other regimens.11

Abacavir/Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Triumeq)

Approval of abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine (Triumeq) in August 2014 was based on SINGLE, a noninferiority trial involving 833 treatment-naive adults that compared dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine (the separate components of Triumeq) to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF. At 96 weeks, more patients in the dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine arm achieved an undetectable HIV viral load (80% versus 72%).13

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Genvoya)

Approval of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was supported by data from two 48-week phase 3, double-blind studies (Studies 104 and 111) involving 1733 treatment-naive patients that compared the regimen to elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild). Both studies demonstrated that elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was statistically noninferior, and it was favored in regard to certain renal and bone laboratory parameters.15 Studies comparing TAF and TDF have demonstrated that TAF is less likely to cause loss of bone mineral density and nephrotoxicity compared to TDF.16,17

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TAF (Odefsey)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TAF was approved based, in part, on positive bioequivalence studies demonstrating that it achieved similar drug levels of emtricitabine and TAF as coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF and similar drug levels of rilpivirine as individually dosed rilpivirine.18 The safety, efficacy, and tolerability of this coformulation is supported by clinical studies of rilpivirine-based therapy and emtricitabine/TAF-based therapy in a range of patients with HIV.18

Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/TAF (Biktarvy)

The coformulation bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF was approved based on 4 phase 3 studies: Studies 1489 and 1490 in treatment-naive adults, and Studies 1844 and 1878 in virologically suppressed adults. In Study 1489, 629 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or coformulated abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. In Study 1490, 645 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or dolutegravir + emtricitabine/TAF. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL).19,20

Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Symtuza)

Approval of coformulated darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was based on data from two 48-week, noninferiority, phase 3 studies that assessed the safety and efficacy of the coformulation versus a control regimen (darunavir/cobicistat plus emtricitabine/TDF) in adults with no prior ART history (AMBER) and in virologically suppressed adults (EMERALD). In the randomized, double-blind, multicenter controlled AMBER trial, at week 48, 91.4% of patients in the study group and 88.4% in the control group achieved viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL), and virologic failure rates were low in both groups (HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL; 4.4% versus 3.3%, respectively).21

Doravirine/Lamivudine/TDF (Delstrigo)

Coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trials, DRIVE-AHEAD and DRIVE-FORWARD. The former trial compared coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF with efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF in 728 treatment-naive patients. At 48 weeks, 84.3% in the doravirine/lamivudine/TDF arm and 80.8% in the efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF arm met the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. Thus, doravirine/lamivudine/TDF showed sustained viral suppression and noninferiority compared to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF.23 The DRIVE-FORWARD trial investigated doravirine compared with ritonavir-boosted darunavir, each in combination with 2 NRTIs (TDF with emtricitabine or abacavir with lamivudine). At week 48, 84% of patients in the doravirine arm and 80% in the ritonavir-boosted darunavir arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.24

Two-Drug, Single-Tablet, Once-Daily Regimens

Experts have long recommended that optimal treatment of HIV must consist of 3 active drugs, with trials both in the United States and Europe demonstrating decreased morbidity and mortality with 3-drug therapy.25,26 However, newer, more potent 2-drug therapy is giving more choices to people living with HIV. The single-tablet, 2-drug regimens currently available are dolutegravir/rilpivirine and dolutegravir/lamivudine. There are theoretical benefits of 2-drug therapy, such as minimizing long-term toxicities, avoidance of some drug-drug interactions, and preservation of drugs for future treatment options. At this time, a 2-drug simplification regimen can be a viable option for selected virologically stable populations.

Dolutegravir/Rilpivirine (Juluca)

Dolutegravir/rilpivirine has been shown to be noninferior to standard therapy at 48-weeks, although it is associated with a higher discontinuation rate because of side effects.27 This option can be particularly useful in patients who have contraindications to NRTIs or renal dysfunction, but it has been studied only in patients without resistance who are already virologically suppressed. Ongoing studies are looking at 2-versus 3-drug therapies for HIV treatment-experienced patients. Most of these use PIs as a backbone because of their potency and high barrier to resistance. The advent of second-generation integrase inhibitors offers additional options.

Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Dovato)

The GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials demonstrated that dolutegravir/lamivudine was noninferior to dolutegravir/TDF/emtricitabine.28 Based on these 2 studies, new guidelines have added dolutegravir/lamivudine as a recommended first-line therapy. For now, the recommendation is to use dolutegravir/lamivudine in individuals where NRTIs are contraindicated, and it should not be used in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Additionally, 3 studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine.29-31 In the TANGO trial, neither virologic failures nor resistant virus were identified at 48 weeks following the switch.32 Although there are benefits of simplification with this regimen, including lower toxicity, lower costs, and saving other NRTIs in case of resistance, there should be no rush to switch patients to a 2-drug regimen. This is a viable strategy in patients without baseline resistance who have preserved T-cells and do not have hepatitis B.

SWITCHING ART AGENTS IN SELECTED CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Virologic Failure

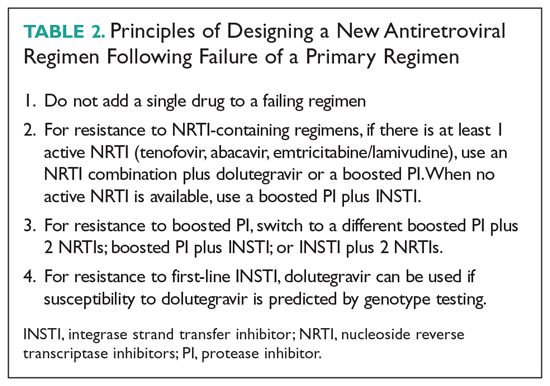

One of the main goals of ART is maximal and durable suppression of HIV viral load to prevent the development of drug-resistant mutations.2 When patients are unable to achieve durable virologic suppression or have virologic rebound, the cause of virologic failure needs to be investigated. Virologic failure is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain viral suppression to a level below 200 copies/mL, whereas rebound is defined as an HIV RNA level exceeding 200 copies/mL after virologic suppression.33 A common cause of virologic failure is patient nonadherence, which can be related to a range of factors, including psychosocial issues and affordability of medications. Innate viral resistance can be the result of transmitted drug resistance at the time of infection or be acquired during unsuppressed viral replication secondary to inherent error-prone reverse transcriptase.33 Pharmacokinetic factors that affect blood levels of ART, such as drug-drug interactions, also can be a key factor in HIV drug resistance.

Patients With Limited Treatment Options

Despite advances in ART, some patients exhaust the existing regimens, leading to development of multidrug resistance and limited treatment options. In light of the treatment challenges in this group of patients, the FDA has recently approved 2 antiretroviral agents to target multidrug-resistant HIV: ibalizumab and fostemsavir.

Pregnancy

ART is used during pregnancy to maintain the pregnant woman’s health and to prevent perinatal transmission. Pregnancy can present unique challenges to effective ART, and therapy decisions should be made based on short-term and long-term safety data, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability. With few exceptions, women who are on a stable ART regimen and present for care should continue the same regimen.38 Key exceptions, due to increased toxicity, include didanosine, indinavir, nelfinavir, stavudine, and treatment-dose ritonavir. Cobicistat-based regimens (atazanavir, darunavir, elvitegravir) have altered pharmacokinetics during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, leading to reduced mean steady-state minimum concentrations.39 Because increasing plasma HIV RNA level is associated with transmission to infants, women continuing cobicistat-based ART treatments should undergo more frequent viral load measurements.40 If viral rebound occurs late in pregnancy, especially shortly before delivery, achieving viral suppression can be more difficult. Therefore, women on a suppressed ART regimen containing cobicistat should consider switching to a different recommended regimen.38

Geriatric Populations

Although HIV is seen predominantly in younger patients, 48% of persons living with HIV are older than 50 years and 8% are 65 years of age or older.46 With effective antiretroviral treatment, we will continue to see an aging population of people living with HIV. There are no specific guidelines regarding the treatment of older adults, but HIV treatment can have its own challenges. Physiologic declines in renal function occur with aging, which can be compounded by an increasing prevalence of diabetes and decreased muscle mass, making estimations of renal function unreliable.47 Physiologic changes with age, such as decline in renal and hepatic function, decreasing metabolism via cytochrome P450, and body composition, influence drug pharmacokinetics and can in turn potentiate drug toxicities.48 Comorbid states and polypharmacy can complicate care. The prevalence of polypharmacy in the elderly is high, 93%, and is increasing.49,50 A study found that in those aged 65 years or older with HIV, 65% had at least 1 potential drug-drug interaction, and 6.6% had a potential severe drug-drug interaction.50 These patients are thus at risk of poor drug adherence, which in HIV therapy can lead to rebound viremia and resistance.

Renal Insufficiency

Several commonly used ART agents have nephrotoxic potential. The most common manifestations of nephrotoxicity are tubular toxicity, crystal nephropathy, and interstitial nephritis. Of these, acute tubular toxicity caused by TDF is the most widely reported. About 2% of those taking TDF developed treatment-limiting renal insufficiency, manifested as Fanconi syndrome.53 Higher plasma levels of TDF are associated with increased nephrotoxicity.55 Guidelines recommend switching from TDF if the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declines by > 25% or the eGFr is < 60/mL/min/1.73 m2. Wever et al reports that in TDF-associated nephrotoxicity, only 42% of patients reached their pre-TDF eGFR.54TAF, a prodrug of TDF, is associated with reduced levels of TDF and is hypothesized to have fewer adverse effects.55 A pooled analysis comparing renal adverse effects of TDF and TAF reported no cases of renal dysfunction in the TAF group, supporting its safety; however, acute kidney injury has also been reported with TAF.56,57 Switching from TDF to TAF in patients with renal dysfunction has been shown to lead to improvement in proteinuria, but the impact remains unclear.53

Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Risk

Aside from the traditional cardiovascular risks, PIs, TAF, and efavirenz can negatively affect the lipid profile, with changes in LDL and triglycerides appearing as early as 2 weeks after initiating therapy. An observational study from Spain showed that treatment with TAF worsens the lipid profile in comparison to patients treated with TDF for elvitegravir/cobicistat-based therapies; patients on TAF were twice as likely to need lipid-lower drugs in comparison to those in the TDF arm.61 Similarly, patients who changed from a TDF-based regimen to TAF for improved renal and bone safety profiles had significant changes in both total cholesterol and LDL.65Other NRTIs do not negatively affect lipid profile. Although NNRTIs can increase LDL, this is usually offset by an increase in HDL.62 Of the NNRTIs, the incidence of increased LDL is higher with efavirenz, but it also can cause an increase in HDL; in contrast, patients switched from efavirenz to rilpivirine have a better lipid profile.63,64 PIs, especially older ones such as lopinavir/ritonavir, are associated with lipid abnormalities. For patients who develop dyslipidemia as a result of using older PIs, switching to a darunavir or atazanavir regimen or even integrase inhibitors, which are considered lipid neutral, is recommended.63 When making adjustments in ART, care should be taken in prescribing abacavir to individuals with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Although there is no consensus, some randomized controlled trials suggested an association between myocardial infarction and abacavir, whereas others have not.66,67

HIV and Hepatis B Co-infection

In patients with HIV and hepatitis B co-infection, ART regimens should contain 1 drug that is active against hepatitis B (lamivudine, emtricitabine, TDF, or TAF). Clinicians should monitor liver function for hepatitis B reactivation and liver function when a regimen that contains anti-hepatitis B drugs is stopped because discontinuation of these regimens can result in acute, and sometimes fatal, liver damage.2

Financial Considerations

With out-of-pocket expenses and co-pays, some patients may have to switch ART regimens for financial reasons. Additionally, switching to generic versions of ART has been proposed as a means of saving resources for government programs already facing budgetary constraints. A study published in 2013 using generic-based ART versus branded ART showed a potential savings of almost $1 billion per year.68 A key barrier to the use of generic-based ART is patient skepticism regarding the performance of these medications. Branded ART regimens are also co-formulated, creating the perception that taking more pills will lead to noncompliance and therefore place the patient at risk of viral rebound. In a study from France, only 17% of patients were willing to switch to generic medications if doing so increased pill burden.69 In the same study, 75% physicians were generally willing to prescribe generics; however, that number dropped to 26% if the patient’s pill burden would increase.69 Paradoxically, because of the patchwork of insurance, government assistance, Medicaid, and Medicare, changing to generic-based ART may increase patients’ co-pays.

1. Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults. 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018; 320:379-396.

2. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/ AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.

3. FDA approves the first once-a-day three-drug combination tablet for treatment of HIV-1. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/769/fda-approves-the-first-once-a-day-three-drug-combination-tablet-for-treatment-of-hiv-1. Accessed July 14, 2020.

4. Apostolova N, Funes HA, Blas-Garcia A, et al. Efavirenz and the CNS: what we already know and questions that need to be answered. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2693-2708.

5. de Béthune MP. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), their discovery, development, and use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review of the last 20 years (1989-2009). Antiviral Res. 2010;85:75-90.

6. Carey D, Puls R, Amin J, et al. Efficacy and safety of efanvirenz 400mg daily versus 600 mg daily: 96-week data from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority ENCORE1 study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:793-802.

7. Molina JM, Cahn P, Grinsztejn B, et al; ECHO study group. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with tenofovir and emtricitabine in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (ECHO): a phase 3 randomised double-blind active-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:238-246.

8. Cohen CJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Clotet B, et al. THRIVE study group Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with two background nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (THRIVE): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:229-237.

9. James C, Preninger L, Sweet M. Rilpivirine: A second-generation nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:857-861.

10. Zolopa A, Sax PE, DeJesus E, et al. GS-US-236-0102 Study Team A randomized double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 96 results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:96-100.

11. DeJesus E, Rockstroh JK, Henry K, et al. GS-236-0103 Study Team Co-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus co-formulated emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:2429-2438.

12. Sherman EM, et al. Cobicistat: review of a pharmacokinetic enhancer for HIV infection. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1876-1893.

13. Walmsley S, Baumgarten A, Berenguer J, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir/lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in antiretroviral therapy-naive patients: week 96 and week 144 results from the SINGLE randomized clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70:515-519.

14. Barbarino JM, Kroetz DL, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: abacavir pathway. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24:276-282.

15. Sax PE, Wohl DA, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomized, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2606–2615.

16. DeJesus E, Haas B, Segal-Maurer S, et al. Superior efficacy and improved renal and bone safety after switching from a tenofovir disoproxil fumarate regimen to a tenofovir alafenamide-based regimen through 96 weeks of treatment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;34:337-342.

17. Maggiolo F, Rizzardini G, Raff F, et al. Bone mineral density in virologically suppressed people aged 60 years or older with HIV-1 switching from a regimen containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to an elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide single-tablet regimen: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2019;6: e655-e666.

18. Ogbuagu O. Rilpivirine, emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide: single-tablet combination for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in selected patients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;;14:1113-1126.

19. Gallant J, Lazzarin A, Mills A, et al. Bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1489): a double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2063-2072.

20. Sax PE, Pozniak A, Montes ML, et al. Coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, for the initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-1490): a randomised, double-blind, multicenter, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2073-2082.

21. Eron JJ, Orkin C, Gallant J, et al. A week-48 randomized phase-3 trial of darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in treatment-naive HIV-1 patients. AIDS. 2018;32:1431-1442.

22. Orkin C, Molina JM, Negredo E, et al;. EMERALD study group. Efficacy and safety of switching from boosted protease inhibitors plus emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate regimens to the once-daily complete HIV-1 regimen of darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (D/C/F/TAF) in virologically suppressed, HIV-1-infected adults through 48 weeks (EMERALD): a phase 3, randomized, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e23-e34.

23. Orkin C, Squires KE, Molina JM, et al. Doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is non-inferior to efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in treatment-naive adults with human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection: week 48 results of the DRIVE-AHEAD Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:535-544.

24. Molina JM, Squires K, Sax PE, et al. Doravirine versus ritonavir-boosted darunavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 (DRIVE-FORWARD): 48-week results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e211-e220.

25. Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman ACE, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853-860.

26. Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfiedl TL. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. Lancet. 1998;3552:1725-1730.

27. Libre JM, Hugh CC, Castelli F, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomized, noninferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet. 2018;391:839-849.

28. Cahn P, Madero JS, Arribas JR, et al. Durable efficacy of dolutegravir plus lamivudine in antiretroviral treatment-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 96-week results from the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 randomized clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;83:310-318.

29. Joly V, Burdet C, Landman R, et al. Dolutegravir and lamivudine maintenance therapy in HIV-1 virologically suppressed patients: results of the ANRS 167 trial (LAMIDOL). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:739-745.

30. Li JZ, Sax PE, Marconi VC, et al. No significant changes to residual viremia after switch to dolutegravir and lamivudine in a randomized trial. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofz056.

31. Taiwo BO, Marconi VC, Verzins B, et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine maintains human immunodeficiency virus-1 suppression through week 48 in a pilot randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1794-1979.

32. Van Wyk J, Ajana F, Bisshop F, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine fixed-dose 2-drug regimen vs continuing a tenofovir alafenamide–based 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phase 3, randomized, noninferiority TANGO Study. Clin Infect Dis. Jan 6;ciz1243. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1243.

33. Cutrell J, Jodlowski T, Bedimo R. The management of treatment-experienced HIV patients (including virologic failure and switches). Ther Adv Infectious Dis. 2020;7:1-15.

34. Devereux, HL, Youle, M, Johnson, MA, et al. Rapid decline in detectability of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations after stopping therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:F123-F127.

35. Gatanaga H, Tsukada K, Honda H, et al. Detection of HIV type 1 load by the Roche Cobas TaqMan assay in patients with viral loads previously undetectable by the Roche Cobas Amplicor Monitor. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:260-262.

36. Emu B, Fessel J, Schrader S, et al. Phase 3 study of ibalizumab for multidrug-resistant HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:645-654.

37. Kozal M, Aberg J, Pialoux G, et al. Fostemsavir in adults with multidrug-resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1232-1243.

38. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1-infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/3/perinatal-guidelines/0/ Accessed on July 13, 2020.

39. Boyd SD, Sampson MR, Viswanathan P, et al. Cobicistat-containing antiretroviral regimens are not recommended during pregnancy: viewpoint. AIDS. 2019;33:1089-1093.

40. Garcia PM, Kalish LA, Pitt J, et al. Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:394-402.

41. Stek A, Best BM, Wang J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once versus twice daily darunavir In pregnant HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70:33-41.

42. Stek A, Best B, Capparelli E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of increased dose darunavir during late pregnancy and postpartum. Presented at: 23rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. 2016. Boston, MA.

43. Mirochnick M, Best BM, Stek AM, et al. Atazanavir pharmacokinetics with and without tenofovir during pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:412-419.

44. Schalkwijk S, Colbers A, Konopnicki D, et al. Lowered rilpivirine exposure during third trimester of pregnancy in HIV-1-positive women. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1335-1341.

45. Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural-tube defects and antiretroviral treatment regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:827-840.

46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; vol. 29. www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018.

47. Rhee MS, Greenblatt DJ. Pharmacologic consideration for the use of antiretroviral agents in the elderly. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;481212-1225.

48. Nguyen, N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

49. Gleason LJ, Luque AE, Shah K. Polypharmacy in the HIV-infected older adult population. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8749-763.

50. Bastida C, Grau A, Marquez M, et al. Polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions in an HIV-infected elderly population. Farm Hosp. 2017;41:618-624.

51. Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1242-1251.

52. Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Ross M, et al. Cumulative and current exposure to potentially nephrotoxic antiretrovirals and development of chronic kidney disease in HIV-positive individuals with a normal baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate: a prospective international cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e23-32.

53. Ryom L, Mocroft A, Kirk O, et al. D:A:D Study Group. Association between antiretroviral exposure and renal impairment among HIV-positive persons with normal baseline renal function: the D:A:D study. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1359.

54. Wever K, van Agtmael MA, Carr A. Incomplete reversibility of tenofovir related renal toxicity in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:78-81.

55. Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011; 57:773-780.

56. Gupta SK, Post FA, Arribas JR, et al. Renal safety of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a pooled analysis of 26 clinical trials. AIDS. 2019;33:1455-1465.

57. Novick TK, Choi MJ, Rosenberg AZ, et al, Tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity in an HIV-positive patient: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8046.

58. Surial B, Ledergerber B, Calmy A, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study, changes in renal function after switching from TDF to TAF in HIV-infected individuals: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. jiaa125, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa125.

59. McLaughlin MM, Guerrero AJ, Merker A. Renal effects of non-tenofovir antiretroviral therapy in patients living with HIV. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212519.

60. German P, Liu H, Szwarcberg J, et al. Effect of cobicistat on glomerular filtration rate in subjects with normal and impaired renal function. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:32-40.

61. Cid-Silva P, Fernandez-Bargiela N, Margusino-Framinan L, et al. Treatment with tenofovir alafenamide fumarate worsens the lipid profile of HIV-infected patients versus treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, each coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124:479-490.

62. Fontas E, van Leth F, Sabin CA, et al. Lipid profiles in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy: are different antiretroviral drugs associated with different lipid profiles?. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1056-1074.

63. Tebas P, Sension M, Arribas J, et al. Lipid levels and changes in body fat distribution in treatment-naive, HIV-1-Infected adults treated with rilpivirine or Efavirenz for 96 weeks in the ECHO and THRIVE trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:425-434.

64. Taramasso L, Tatarelli P, Ricci E, et al. Improvement of lipid profile after switching from efavirenz or ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors to rilpivirine or once-daily integrase inhibitors: results from a large observational cohort study (SCOLTA). BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:357.

65. Lacey A, Savinelli, S, Barco, EA, et al. The UCD ID Cohort Study; Investigating the effect of antiretroviral switch to tenofovir alafenamide on lipid profiles in people living with HIV. AIDS. 2020;341161-1170.

66. Marcus JL, Neugebauer RS, Leyden WA, et al. Use of abacavir and risk of cardiovascular disease among HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71:413-419.

67. Ribaudo HJ, Benson CA, Zheng Y, et al. No risk of myocardial infarction associated with initial antiretroviral treatment containing abacavir: short and long-term results from ACTG A5001/ALLRT. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:929-940.

68. Walensky RP, Sax PE, Nakamura YM, et al. Economic savings versus health losses: the cost-effectiveness of generic antiretroviral therapy in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:84-92.

69. Jacomet C, Allavena C, Peyrol F, et al. Perception of antiretroviral generic medicines: one-day survey of HIV-infected patients and their physicians in France. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117214-e0117214.

A 57-year-old man living with HIV has been followed at a local infectious disease clinic for more than 15 years. He acquired HIV disease through heterosexual contact. He lives alone and works at a convenience store; he has not been sexually active for the past 5 years. He smokes 10 cigarettes a day, but does not drink alcohol or use illicit drugs. He had been on coformulated emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and coformulated lopinavir/ritonavir, which he had taken conscientiously, since May 2008, without noticing any adverse reactions from this regimen. His HIV viral load had been undetectable, and his CD4 count had hovered between 600 and 700 cells/µL. Although he was on atorvastatin for dyslipidemia, his fasting lipid profile, performed in 2018, revealed a total cholesterol level of 200 mg/dL;triglyceride, 247 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 43 mg/dL; and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 132 mg/dL. In April 2019, his HIV regimen was switched to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Blood tests performed in December 2019 revealed undetectable HIV viral load; an increased CD4 count to 849 cell/µL; total cholesterol, 140 mg/dL; triglyceride, 115 mg/dL; HDL, 60 mg/dL; and LDL, 90 mg/dL.

SIMPLIFYING ART

Virologically Suppressed Patients Without Drug-Resistant Virus

Treatment adherence is of paramount importance to ensure treatment success. Patients with a viral load that is undetectable or nearly undetectable without drug resistance could be taking ART regimens consisting of more than 1 pill and/or that require more than once-daily dosing. Decreasing pill burden or dosing frequency can help to improve adherence to treatment. In addition, older-generation ART agents are usually more toxic and less potent than newer-generation agents, so another important objective of switching older drugs to newer drugs is to decrease adverse reactions and improve virologic suppression. Selection of an ART regimen should be guided by the results of resistance testing (genotyping and phenotyping tests) and previous treatment history. After switching a patient’s ART regimen, plasma HIV viral load and CD4 count should be closely monitored.2 The following 3-drug, single-tablet, once-daily ART regimens can be used in patients who are virologically stable (ordered chronologically by FDA approval dates).

Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla)

Coformulated efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF was the first single-tablet, once-daily, fixed-dose combination approved by the FDA (July 2006). Approval was based on a 48- week clinical trial involving 244 adults with HIV infection that showed that 80% of participants achieved a marked reduction in HIV viral load and a significant increase in CD4 cell count.3 Of the 3 components, efavirenz has unique central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects that could reduce adherence. Patients who were started on this fixed-dose combination commonly reported dizziness, headache, nightmare, insomnia, and impaired concentration.4 However, the CNS side effects resolved within the first 4 weeks of therapy, and less than 5% of patients quit taking the drug. Primate studies showed efavirenz is teratogenic, but studies in pregnant women did not find efavirenz to be more teratogenic than other ART agents.5

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TDF (Complera)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TDF was approved based on data from two 48-week, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials (ECHO and THRIVE) that evaluated the safety and efficacy of rilpivirine compared to efavirenz among treatment-naive adults with HIV infection.7,8 Rilpivirine is well tolerated and causes fewer CNS symptoms compared to efavirenz. The main caveat for rilpivirine is drug-drug interactions. It should not be coadministered with CYP inducers, such as rifampin, phenytoin, or St. John’s wort, as coadministration can cause subtherapeutic blood levels of rilpivirine. Because increased levels of rilpivirine can prolong QTc on electrocardiogram (ECG), an ECG should be obtained before starting an ART regimen that contains rilpivirine, especially in the presence of CYP 3A4 inhibitors.9

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild)

This coformulation was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled trials, Study 102 and Study 103, in treatment-naive patients with HIV (n = 1408). In Study 102, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla).10 In Study 103, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or atazanavir + ritonavir + emtricitabine/TDF. In both studies, the primary endpoint was virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) at 48 weeks, and elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF was noninferior compared to the other regimens.11

Abacavir/Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Triumeq)

Approval of abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine (Triumeq) in August 2014 was based on SINGLE, a noninferiority trial involving 833 treatment-naive adults that compared dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine (the separate components of Triumeq) to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF. At 96 weeks, more patients in the dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine arm achieved an undetectable HIV viral load (80% versus 72%).13

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Genvoya)

Approval of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was supported by data from two 48-week phase 3, double-blind studies (Studies 104 and 111) involving 1733 treatment-naive patients that compared the regimen to elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild). Both studies demonstrated that elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was statistically noninferior, and it was favored in regard to certain renal and bone laboratory parameters.15 Studies comparing TAF and TDF have demonstrated that TAF is less likely to cause loss of bone mineral density and nephrotoxicity compared to TDF.16,17

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TAF (Odefsey)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TAF was approved based, in part, on positive bioequivalence studies demonstrating that it achieved similar drug levels of emtricitabine and TAF as coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF and similar drug levels of rilpivirine as individually dosed rilpivirine.18 The safety, efficacy, and tolerability of this coformulation is supported by clinical studies of rilpivirine-based therapy and emtricitabine/TAF-based therapy in a range of patients with HIV.18

Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/TAF (Biktarvy)

The coformulation bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF was approved based on 4 phase 3 studies: Studies 1489 and 1490 in treatment-naive adults, and Studies 1844 and 1878 in virologically suppressed adults. In Study 1489, 629 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or coformulated abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. In Study 1490, 645 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or dolutegravir + emtricitabine/TAF. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL).19,20

Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Symtuza)

Approval of coformulated darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was based on data from two 48-week, noninferiority, phase 3 studies that assessed the safety and efficacy of the coformulation versus a control regimen (darunavir/cobicistat plus emtricitabine/TDF) in adults with no prior ART history (AMBER) and in virologically suppressed adults (EMERALD). In the randomized, double-blind, multicenter controlled AMBER trial, at week 48, 91.4% of patients in the study group and 88.4% in the control group achieved viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL), and virologic failure rates were low in both groups (HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL; 4.4% versus 3.3%, respectively).21

Doravirine/Lamivudine/TDF (Delstrigo)

Coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trials, DRIVE-AHEAD and DRIVE-FORWARD. The former trial compared coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF with efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF in 728 treatment-naive patients. At 48 weeks, 84.3% in the doravirine/lamivudine/TDF arm and 80.8% in the efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF arm met the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. Thus, doravirine/lamivudine/TDF showed sustained viral suppression and noninferiority compared to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF.23 The DRIVE-FORWARD trial investigated doravirine compared with ritonavir-boosted darunavir, each in combination with 2 NRTIs (TDF with emtricitabine or abacavir with lamivudine). At week 48, 84% of patients in the doravirine arm and 80% in the ritonavir-boosted darunavir arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.24

Two-Drug, Single-Tablet, Once-Daily Regimens

Experts have long recommended that optimal treatment of HIV must consist of 3 active drugs, with trials both in the United States and Europe demonstrating decreased morbidity and mortality with 3-drug therapy.25,26 However, newer, more potent 2-drug therapy is giving more choices to people living with HIV. The single-tablet, 2-drug regimens currently available are dolutegravir/rilpivirine and dolutegravir/lamivudine. There are theoretical benefits of 2-drug therapy, such as minimizing long-term toxicities, avoidance of some drug-drug interactions, and preservation of drugs for future treatment options. At this time, a 2-drug simplification regimen can be a viable option for selected virologically stable populations.

Dolutegravir/Rilpivirine (Juluca)

Dolutegravir/rilpivirine has been shown to be noninferior to standard therapy at 48-weeks, although it is associated with a higher discontinuation rate because of side effects.27 This option can be particularly useful in patients who have contraindications to NRTIs or renal dysfunction, but it has been studied only in patients without resistance who are already virologically suppressed. Ongoing studies are looking at 2-versus 3-drug therapies for HIV treatment-experienced patients. Most of these use PIs as a backbone because of their potency and high barrier to resistance. The advent of second-generation integrase inhibitors offers additional options.

Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Dovato)

The GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials demonstrated that dolutegravir/lamivudine was noninferior to dolutegravir/TDF/emtricitabine.28 Based on these 2 studies, new guidelines have added dolutegravir/lamivudine as a recommended first-line therapy. For now, the recommendation is to use dolutegravir/lamivudine in individuals where NRTIs are contraindicated, and it should not be used in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Additionally, 3 studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine.29-31 In the TANGO trial, neither virologic failures nor resistant virus were identified at 48 weeks following the switch.32 Although there are benefits of simplification with this regimen, including lower toxicity, lower costs, and saving other NRTIs in case of resistance, there should be no rush to switch patients to a 2-drug regimen. This is a viable strategy in patients without baseline resistance who have preserved T-cells and do not have hepatitis B.

SWITCHING ART AGENTS IN SELECTED CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Virologic Failure

One of the main goals of ART is maximal and durable suppression of HIV viral load to prevent the development of drug-resistant mutations.2 When patients are unable to achieve durable virologic suppression or have virologic rebound, the cause of virologic failure needs to be investigated. Virologic failure is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain viral suppression to a level below 200 copies/mL, whereas rebound is defined as an HIV RNA level exceeding 200 copies/mL after virologic suppression.33 A common cause of virologic failure is patient nonadherence, which can be related to a range of factors, including psychosocial issues and affordability of medications. Innate viral resistance can be the result of transmitted drug resistance at the time of infection or be acquired during unsuppressed viral replication secondary to inherent error-prone reverse transcriptase.33 Pharmacokinetic factors that affect blood levels of ART, such as drug-drug interactions, also can be a key factor in HIV drug resistance.

Patients With Limited Treatment Options

Despite advances in ART, some patients exhaust the existing regimens, leading to development of multidrug resistance and limited treatment options. In light of the treatment challenges in this group of patients, the FDA has recently approved 2 antiretroviral agents to target multidrug-resistant HIV: ibalizumab and fostemsavir.

Pregnancy

ART is used during pregnancy to maintain the pregnant woman’s health and to prevent perinatal transmission. Pregnancy can present unique challenges to effective ART, and therapy decisions should be made based on short-term and long-term safety data, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability. With few exceptions, women who are on a stable ART regimen and present for care should continue the same regimen.38 Key exceptions, due to increased toxicity, include didanosine, indinavir, nelfinavir, stavudine, and treatment-dose ritonavir. Cobicistat-based regimens (atazanavir, darunavir, elvitegravir) have altered pharmacokinetics during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, leading to reduced mean steady-state minimum concentrations.39 Because increasing plasma HIV RNA level is associated with transmission to infants, women continuing cobicistat-based ART treatments should undergo more frequent viral load measurements.40 If viral rebound occurs late in pregnancy, especially shortly before delivery, achieving viral suppression can be more difficult. Therefore, women on a suppressed ART regimen containing cobicistat should consider switching to a different recommended regimen.38

Geriatric Populations

Although HIV is seen predominantly in younger patients, 48% of persons living with HIV are older than 50 years and 8% are 65 years of age or older.46 With effective antiretroviral treatment, we will continue to see an aging population of people living with HIV. There are no specific guidelines regarding the treatment of older adults, but HIV treatment can have its own challenges. Physiologic declines in renal function occur with aging, which can be compounded by an increasing prevalence of diabetes and decreased muscle mass, making estimations of renal function unreliable.47 Physiologic changes with age, such as decline in renal and hepatic function, decreasing metabolism via cytochrome P450, and body composition, influence drug pharmacokinetics and can in turn potentiate drug toxicities.48 Comorbid states and polypharmacy can complicate care. The prevalence of polypharmacy in the elderly is high, 93%, and is increasing.49,50 A study found that in those aged 65 years or older with HIV, 65% had at least 1 potential drug-drug interaction, and 6.6% had a potential severe drug-drug interaction.50 These patients are thus at risk of poor drug adherence, which in HIV therapy can lead to rebound viremia and resistance.

Renal Insufficiency

Several commonly used ART agents have nephrotoxic potential. The most common manifestations of nephrotoxicity are tubular toxicity, crystal nephropathy, and interstitial nephritis. Of these, acute tubular toxicity caused by TDF is the most widely reported. About 2% of those taking TDF developed treatment-limiting renal insufficiency, manifested as Fanconi syndrome.53 Higher plasma levels of TDF are associated with increased nephrotoxicity.55 Guidelines recommend switching from TDF if the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declines by > 25% or the eGFr is < 60/mL/min/1.73 m2. Wever et al reports that in TDF-associated nephrotoxicity, only 42% of patients reached their pre-TDF eGFR.54TAF, a prodrug of TDF, is associated with reduced levels of TDF and is hypothesized to have fewer adverse effects.55 A pooled analysis comparing renal adverse effects of TDF and TAF reported no cases of renal dysfunction in the TAF group, supporting its safety; however, acute kidney injury has also been reported with TAF.56,57 Switching from TDF to TAF in patients with renal dysfunction has been shown to lead to improvement in proteinuria, but the impact remains unclear.53

Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Risk

Aside from the traditional cardiovascular risks, PIs, TAF, and efavirenz can negatively affect the lipid profile, with changes in LDL and triglycerides appearing as early as 2 weeks after initiating therapy. An observational study from Spain showed that treatment with TAF worsens the lipid profile in comparison to patients treated with TDF for elvitegravir/cobicistat-based therapies; patients on TAF were twice as likely to need lipid-lower drugs in comparison to those in the TDF arm.61 Similarly, patients who changed from a TDF-based regimen to TAF for improved renal and bone safety profiles had significant changes in both total cholesterol and LDL.65Other NRTIs do not negatively affect lipid profile. Although NNRTIs can increase LDL, this is usually offset by an increase in HDL.62 Of the NNRTIs, the incidence of increased LDL is higher with efavirenz, but it also can cause an increase in HDL; in contrast, patients switched from efavirenz to rilpivirine have a better lipid profile.63,64 PIs, especially older ones such as lopinavir/ritonavir, are associated with lipid abnormalities. For patients who develop dyslipidemia as a result of using older PIs, switching to a darunavir or atazanavir regimen or even integrase inhibitors, which are considered lipid neutral, is recommended.63 When making adjustments in ART, care should be taken in prescribing abacavir to individuals with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Although there is no consensus, some randomized controlled trials suggested an association between myocardial infarction and abacavir, whereas others have not.66,67

HIV and Hepatis B Co-infection

In patients with HIV and hepatitis B co-infection, ART regimens should contain 1 drug that is active against hepatitis B (lamivudine, emtricitabine, TDF, or TAF). Clinicians should monitor liver function for hepatitis B reactivation and liver function when a regimen that contains anti-hepatitis B drugs is stopped because discontinuation of these regimens can result in acute, and sometimes fatal, liver damage.2

Financial Considerations

With out-of-pocket expenses and co-pays, some patients may have to switch ART regimens for financial reasons. Additionally, switching to generic versions of ART has been proposed as a means of saving resources for government programs already facing budgetary constraints. A study published in 2013 using generic-based ART versus branded ART showed a potential savings of almost $1 billion per year.68 A key barrier to the use of generic-based ART is patient skepticism regarding the performance of these medications. Branded ART regimens are also co-formulated, creating the perception that taking more pills will lead to noncompliance and therefore place the patient at risk of viral rebound. In a study from France, only 17% of patients were willing to switch to generic medications if doing so increased pill burden.69 In the same study, 75% physicians were generally willing to prescribe generics; however, that number dropped to 26% if the patient’s pill burden would increase.69 Paradoxically, because of the patchwork of insurance, government assistance, Medicaid, and Medicare, changing to generic-based ART may increase patients’ co-pays.

A 57-year-old man living with HIV has been followed at a local infectious disease clinic for more than 15 years. He acquired HIV disease through heterosexual contact. He lives alone and works at a convenience store; he has not been sexually active for the past 5 years. He smokes 10 cigarettes a day, but does not drink alcohol or use illicit drugs. He had been on coformulated emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and coformulated lopinavir/ritonavir, which he had taken conscientiously, since May 2008, without noticing any adverse reactions from this regimen. His HIV viral load had been undetectable, and his CD4 count had hovered between 600 and 700 cells/µL. Although he was on atorvastatin for dyslipidemia, his fasting lipid profile, performed in 2018, revealed a total cholesterol level of 200 mg/dL;triglyceride, 247 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 43 mg/dL; and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 132 mg/dL. In April 2019, his HIV regimen was switched to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Blood tests performed in December 2019 revealed undetectable HIV viral load; an increased CD4 count to 849 cell/µL; total cholesterol, 140 mg/dL; triglyceride, 115 mg/dL; HDL, 60 mg/dL; and LDL, 90 mg/dL.

SIMPLIFYING ART

Virologically Suppressed Patients Without Drug-Resistant Virus

Treatment adherence is of paramount importance to ensure treatment success. Patients with a viral load that is undetectable or nearly undetectable without drug resistance could be taking ART regimens consisting of more than 1 pill and/or that require more than once-daily dosing. Decreasing pill burden or dosing frequency can help to improve adherence to treatment. In addition, older-generation ART agents are usually more toxic and less potent than newer-generation agents, so another important objective of switching older drugs to newer drugs is to decrease adverse reactions and improve virologic suppression. Selection of an ART regimen should be guided by the results of resistance testing (genotyping and phenotyping tests) and previous treatment history. After switching a patient’s ART regimen, plasma HIV viral load and CD4 count should be closely monitored.2 The following 3-drug, single-tablet, once-daily ART regimens can be used in patients who are virologically stable (ordered chronologically by FDA approval dates).

Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla)

Coformulated efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF was the first single-tablet, once-daily, fixed-dose combination approved by the FDA (July 2006). Approval was based on a 48- week clinical trial involving 244 adults with HIV infection that showed that 80% of participants achieved a marked reduction in HIV viral load and a significant increase in CD4 cell count.3 Of the 3 components, efavirenz has unique central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects that could reduce adherence. Patients who were started on this fixed-dose combination commonly reported dizziness, headache, nightmare, insomnia, and impaired concentration.4 However, the CNS side effects resolved within the first 4 weeks of therapy, and less than 5% of patients quit taking the drug. Primate studies showed efavirenz is teratogenic, but studies in pregnant women did not find efavirenz to be more teratogenic than other ART agents.5

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TDF (Complera)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TDF was approved based on data from two 48-week, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials (ECHO and THRIVE) that evaluated the safety and efficacy of rilpivirine compared to efavirenz among treatment-naive adults with HIV infection.7,8 Rilpivirine is well tolerated and causes fewer CNS symptoms compared to efavirenz. The main caveat for rilpivirine is drug-drug interactions. It should not be coadministered with CYP inducers, such as rifampin, phenytoin, or St. John’s wort, as coadministration can cause subtherapeutic blood levels of rilpivirine. Because increased levels of rilpivirine can prolong QTc on electrocardiogram (ECG), an ECG should be obtained before starting an ART regimen that contains rilpivirine, especially in the presence of CYP 3A4 inhibitors.9

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild)

This coformulation was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled trials, Study 102 and Study 103, in treatment-naive patients with HIV (n = 1408). In Study 102, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla).10 In Study 103, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or atazanavir + ritonavir + emtricitabine/TDF. In both studies, the primary endpoint was virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) at 48 weeks, and elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF was noninferior compared to the other regimens.11

Abacavir/Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Triumeq)

Approval of abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine (Triumeq) in August 2014 was based on SINGLE, a noninferiority trial involving 833 treatment-naive adults that compared dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine (the separate components of Triumeq) to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF. At 96 weeks, more patients in the dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine arm achieved an undetectable HIV viral load (80% versus 72%).13

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Genvoya)

Approval of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was supported by data from two 48-week phase 3, double-blind studies (Studies 104 and 111) involving 1733 treatment-naive patients that compared the regimen to elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild). Both studies demonstrated that elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was statistically noninferior, and it was favored in regard to certain renal and bone laboratory parameters.15 Studies comparing TAF and TDF have demonstrated that TAF is less likely to cause loss of bone mineral density and nephrotoxicity compared to TDF.16,17

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TAF (Odefsey)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TAF was approved based, in part, on positive bioequivalence studies demonstrating that it achieved similar drug levels of emtricitabine and TAF as coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF and similar drug levels of rilpivirine as individually dosed rilpivirine.18 The safety, efficacy, and tolerability of this coformulation is supported by clinical studies of rilpivirine-based therapy and emtricitabine/TAF-based therapy in a range of patients with HIV.18

Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/TAF (Biktarvy)

The coformulation bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF was approved based on 4 phase 3 studies: Studies 1489 and 1490 in treatment-naive adults, and Studies 1844 and 1878 in virologically suppressed adults. In Study 1489, 629 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or coformulated abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. In Study 1490, 645 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or dolutegravir + emtricitabine/TAF. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL).19,20

Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Symtuza)

Approval of coformulated darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was based on data from two 48-week, noninferiority, phase 3 studies that assessed the safety and efficacy of the coformulation versus a control regimen (darunavir/cobicistat plus emtricitabine/TDF) in adults with no prior ART history (AMBER) and in virologically suppressed adults (EMERALD). In the randomized, double-blind, multicenter controlled AMBER trial, at week 48, 91.4% of patients in the study group and 88.4% in the control group achieved viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL), and virologic failure rates were low in both groups (HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL; 4.4% versus 3.3%, respectively).21

Doravirine/Lamivudine/TDF (Delstrigo)

Coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trials, DRIVE-AHEAD and DRIVE-FORWARD. The former trial compared coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF with efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF in 728 treatment-naive patients. At 48 weeks, 84.3% in the doravirine/lamivudine/TDF arm and 80.8% in the efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF arm met the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. Thus, doravirine/lamivudine/TDF showed sustained viral suppression and noninferiority compared to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF.23 The DRIVE-FORWARD trial investigated doravirine compared with ritonavir-boosted darunavir, each in combination with 2 NRTIs (TDF with emtricitabine or abacavir with lamivudine). At week 48, 84% of patients in the doravirine arm and 80% in the ritonavir-boosted darunavir arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.24

Two-Drug, Single-Tablet, Once-Daily Regimens

Experts have long recommended that optimal treatment of HIV must consist of 3 active drugs, with trials both in the United States and Europe demonstrating decreased morbidity and mortality with 3-drug therapy.25,26 However, newer, more potent 2-drug therapy is giving more choices to people living with HIV. The single-tablet, 2-drug regimens currently available are dolutegravir/rilpivirine and dolutegravir/lamivudine. There are theoretical benefits of 2-drug therapy, such as minimizing long-term toxicities, avoidance of some drug-drug interactions, and preservation of drugs for future treatment options. At this time, a 2-drug simplification regimen can be a viable option for selected virologically stable populations.

Dolutegravir/Rilpivirine (Juluca)

Dolutegravir/rilpivirine has been shown to be noninferior to standard therapy at 48-weeks, although it is associated with a higher discontinuation rate because of side effects.27 This option can be particularly useful in patients who have contraindications to NRTIs or renal dysfunction, but it has been studied only in patients without resistance who are already virologically suppressed. Ongoing studies are looking at 2-versus 3-drug therapies for HIV treatment-experienced patients. Most of these use PIs as a backbone because of their potency and high barrier to resistance. The advent of second-generation integrase inhibitors offers additional options.

Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Dovato)

The GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials demonstrated that dolutegravir/lamivudine was noninferior to dolutegravir/TDF/emtricitabine.28 Based on these 2 studies, new guidelines have added dolutegravir/lamivudine as a recommended first-line therapy. For now, the recommendation is to use dolutegravir/lamivudine in individuals where NRTIs are contraindicated, and it should not be used in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Additionally, 3 studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine.29-31 In the TANGO trial, neither virologic failures nor resistant virus were identified at 48 weeks following the switch.32 Although there are benefits of simplification with this regimen, including lower toxicity, lower costs, and saving other NRTIs in case of resistance, there should be no rush to switch patients to a 2-drug regimen. This is a viable strategy in patients without baseline resistance who have preserved T-cells and do not have hepatitis B.

SWITCHING ART AGENTS IN SELECTED CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Virologic Failure

One of the main goals of ART is maximal and durable suppression of HIV viral load to prevent the development of drug-resistant mutations.2 When patients are unable to achieve durable virologic suppression or have virologic rebound, the cause of virologic failure needs to be investigated. Virologic failure is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain viral suppression to a level below 200 copies/mL, whereas rebound is defined as an HIV RNA level exceeding 200 copies/mL after virologic suppression.33 A common cause of virologic failure is patient nonadherence, which can be related to a range of factors, including psychosocial issues and affordability of medications. Innate viral resistance can be the result of transmitted drug resistance at the time of infection or be acquired during unsuppressed viral replication secondary to inherent error-prone reverse transcriptase.33 Pharmacokinetic factors that affect blood levels of ART, such as drug-drug interactions, also can be a key factor in HIV drug resistance.

Patients With Limited Treatment Options

Despite advances in ART, some patients exhaust the existing regimens, leading to development of multidrug resistance and limited treatment options. In light of the treatment challenges in this group of patients, the FDA has recently approved 2 antiretroviral agents to target multidrug-resistant HIV: ibalizumab and fostemsavir.

Pregnancy

ART is used during pregnancy to maintain the pregnant woman’s health and to prevent perinatal transmission. Pregnancy can present unique challenges to effective ART, and therapy decisions should be made based on short-term and long-term safety data, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability. With few exceptions, women who are on a stable ART regimen and present for care should continue the same regimen.38 Key exceptions, due to increased toxicity, include didanosine, indinavir, nelfinavir, stavudine, and treatment-dose ritonavir. Cobicistat-based regimens (atazanavir, darunavir, elvitegravir) have altered pharmacokinetics during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, leading to reduced mean steady-state minimum concentrations.39 Because increasing plasma HIV RNA level is associated with transmission to infants, women continuing cobicistat-based ART treatments should undergo more frequent viral load measurements.40 If viral rebound occurs late in pregnancy, especially shortly before delivery, achieving viral suppression can be more difficult. Therefore, women on a suppressed ART regimen containing cobicistat should consider switching to a different recommended regimen.38

Geriatric Populations

Although HIV is seen predominantly in younger patients, 48% of persons living with HIV are older than 50 years and 8% are 65 years of age or older.46 With effective antiretroviral treatment, we will continue to see an aging population of people living with HIV. There are no specific guidelines regarding the treatment of older adults, but HIV treatment can have its own challenges. Physiologic declines in renal function occur with aging, which can be compounded by an increasing prevalence of diabetes and decreased muscle mass, making estimations of renal function unreliable.47 Physiologic changes with age, such as decline in renal and hepatic function, decreasing metabolism via cytochrome P450, and body composition, influence drug pharmacokinetics and can in turn potentiate drug toxicities.48 Comorbid states and polypharmacy can complicate care. The prevalence of polypharmacy in the elderly is high, 93%, and is increasing.49,50 A study found that in those aged 65 years or older with HIV, 65% had at least 1 potential drug-drug interaction, and 6.6% had a potential severe drug-drug interaction.50 These patients are thus at risk of poor drug adherence, which in HIV therapy can lead to rebound viremia and resistance.

Renal Insufficiency

Several commonly used ART agents have nephrotoxic potential. The most common manifestations of nephrotoxicity are tubular toxicity, crystal nephropathy, and interstitial nephritis. Of these, acute tubular toxicity caused by TDF is the most widely reported. About 2% of those taking TDF developed treatment-limiting renal insufficiency, manifested as Fanconi syndrome.53 Higher plasma levels of TDF are associated with increased nephrotoxicity.55 Guidelines recommend switching from TDF if the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declines by > 25% or the eGFr is < 60/mL/min/1.73 m2. Wever et al reports that in TDF-associated nephrotoxicity, only 42% of patients reached their pre-TDF eGFR.54TAF, a prodrug of TDF, is associated with reduced levels of TDF and is hypothesized to have fewer adverse effects.55 A pooled analysis comparing renal adverse effects of TDF and TAF reported no cases of renal dysfunction in the TAF group, supporting its safety; however, acute kidney injury has also been reported with TAF.56,57 Switching from TDF to TAF in patients with renal dysfunction has been shown to lead to improvement in proteinuria, but the impact remains unclear.53

Dyslipidemia and Cardiovascular Risk

Aside from the traditional cardiovascular risks, PIs, TAF, and efavirenz can negatively affect the lipid profile, with changes in LDL and triglycerides appearing as early as 2 weeks after initiating therapy. An observational study from Spain showed that treatment with TAF worsens the lipid profile in comparison to patients treated with TDF for elvitegravir/cobicistat-based therapies; patients on TAF were twice as likely to need lipid-lower drugs in comparison to those in the TDF arm.61 Similarly, patients who changed from a TDF-based regimen to TAF for improved renal and bone safety profiles had significant changes in both total cholesterol and LDL.65Other NRTIs do not negatively affect lipid profile. Although NNRTIs can increase LDL, this is usually offset by an increase in HDL.62 Of the NNRTIs, the incidence of increased LDL is higher with efavirenz, but it also can cause an increase in HDL; in contrast, patients switched from efavirenz to rilpivirine have a better lipid profile.63,64 PIs, especially older ones such as lopinavir/ritonavir, are associated with lipid abnormalities. For patients who develop dyslipidemia as a result of using older PIs, switching to a darunavir or atazanavir regimen or even integrase inhibitors, which are considered lipid neutral, is recommended.63 When making adjustments in ART, care should be taken in prescribing abacavir to individuals with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Although there is no consensus, some randomized controlled trials suggested an association between myocardial infarction and abacavir, whereas others have not.66,67

HIV and Hepatis B Co-infection

In patients with HIV and hepatitis B co-infection, ART regimens should contain 1 drug that is active against hepatitis B (lamivudine, emtricitabine, TDF, or TAF). Clinicians should monitor liver function for hepatitis B reactivation and liver function when a regimen that contains anti-hepatitis B drugs is stopped because discontinuation of these regimens can result in acute, and sometimes fatal, liver damage.2

Financial Considerations

With out-of-pocket expenses and co-pays, some patients may have to switch ART regimens for financial reasons. Additionally, switching to generic versions of ART has been proposed as a means of saving resources for government programs already facing budgetary constraints. A study published in 2013 using generic-based ART versus branded ART showed a potential savings of almost $1 billion per year.68 A key barrier to the use of generic-based ART is patient skepticism regarding the performance of these medications. Branded ART regimens are also co-formulated, creating the perception that taking more pills will lead to noncompliance and therefore place the patient at risk of viral rebound. In a study from France, only 17% of patients were willing to switch to generic medications if doing so increased pill burden.69 In the same study, 75% physicians were generally willing to prescribe generics; however, that number dropped to 26% if the patient’s pill burden would increase.69 Paradoxically, because of the patchwork of insurance, government assistance, Medicaid, and Medicare, changing to generic-based ART may increase patients’ co-pays.

1. Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults. 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018; 320:379-396.

2. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/ AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.

3. FDA approves the first once-a-day three-drug combination tablet for treatment of HIV-1. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/769/fda-approves-the-first-once-a-day-three-drug-combination-tablet-for-treatment-of-hiv-1. Accessed July 14, 2020.

4. Apostolova N, Funes HA, Blas-Garcia A, et al. Efavirenz and the CNS: what we already know and questions that need to be answered. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2693-2708.

5. de Béthune MP. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), their discovery, development, and use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review of the last 20 years (1989-2009). Antiviral Res. 2010;85:75-90.

6. Carey D, Puls R, Amin J, et al. Efficacy and safety of efanvirenz 400mg daily versus 600 mg daily: 96-week data from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority ENCORE1 study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:793-802.

7. Molina JM, Cahn P, Grinsztejn B, et al; ECHO study group. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with tenofovir and emtricitabine in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (ECHO): a phase 3 randomised double-blind active-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:238-246.

8. Cohen CJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Clotet B, et al. THRIVE study group Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with two background nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (THRIVE): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:229-237.

9. James C, Preninger L, Sweet M. Rilpivirine: A second-generation nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:857-861.

10. Zolopa A, Sax PE, DeJesus E, et al. GS-US-236-0102 Study Team A randomized double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 96 results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:96-100.

11. DeJesus E, Rockstroh JK, Henry K, et al. GS-236-0103 Study Team Co-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus co-formulated emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:2429-2438.

12. Sherman EM, et al. Cobicistat: review of a pharmacokinetic enhancer for HIV infection. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1876-1893.

13. Walmsley S, Baumgarten A, Berenguer J, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir/lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in antiretroviral therapy-naive patients: week 96 and week 144 results from the SINGLE randomized clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70:515-519.

14. Barbarino JM, Kroetz DL, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: abacavir pathway. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24:276-282.