User login

Borderline personality disorder diagnosis: To tell or not to tell patients?

News of actor/comedian Pete Davidson expressing relief after finally receiving a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) prompted a recent Twitter discussion among physicians regarding the ongoing debate on whether or not to tell a patient he or she has this diagnosis.

“I’ve heard from [many] trainees that they were told never to tell a patient they had BPD, but I can hardly think of anything more paternalistic and stigmatizing,” Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of community psychiatry at University of California, Davis, tweeted.

“Most patients, when I explain it to them, have this kind of reaction – they feel relieved and understood,” she added.

“I was told that as well [not to tell] in one of my practicum placements,” one respondent who identified herself as a clinical/forensic psychologist tweeted back. “I said it anyway and the person was relieved there was a name for what they were living with.”

However, others disagreed with Dr. Barnhorst, noting that BPD is a very serious, stigmatizing, and challenging disorder to treat and, because of this, may cause patients to lose hope.

Still, Dr. Barnhorst stands by her position. Although “there is a negative stigma against a diagnosis of BPD,” that idea more often comes from the clinician instead of the patient, she said.

“I’ve never had a patient say, ‘how dare you call me that!’ like it was an insult,” she said in an interview. Not disclosing a diagnosis “is like you’re not trusting a patient to be a reasonable adult human about this.”

‘Hard diagnosis’

Although BPD is a “hard diagnosis, we would never withhold a diagnosis of cancer or liver disease or something else we knew patients didn’t want but that we were going to try and treat them for,” said Dr. Barnhorst.

BPD is linked to significant morbidity because of its common association with comorbid conditions, such as major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and dysthymia. A history of self-harm is present in 70%-75% of these patients and some estimates suggest up to 9% of individuals with BPD die by suicide.

In an article published in Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience investigators discussed “ethical and clinical questions psychiatrists should consider” when treating BPD, including whether a diagnosis should be shared with a patient.

After such a diagnosis a patient may “react intensely in negative ways and these responses may be easily triggered,” the researchers wrote.

“A propensity that will likely cause psychiatrists anguish, however, is BPD patients’ increased likelihood of attempting suicide,” they added. Part of the problem has been that, in the past, it was thought that a BPD prognosis was untreatable. However, the researchers note that is no longer the case.

Still, Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, has labeled BPD a so-called “asterisk” disorder.

As she wrote in a recent blog, “We tell patients when they meet criteria for a medical diagnosis.* We show compassion and nonjudgmentalism to patients.* We do not discriminate against patients.*” However, the asterisk for each of these statements is: *Except for those with BPD.

Ongoing debate

Starting around the 1980s, the DSM listed personality disorders under the No. 2 Axis, which is for conditions with symptoms that are “not mitigatable,” said Dr. Nelson.

“It really started as well-meaning therapists who care about their patients who wanted to develop some precision in understanding people, and them starting to notice some patterns that can get in the way of optimal function,” she said in an interview.

The thought was not to disclose these diagnoses “because that was for you to understand, and for the patient to discover these patterns over time in the course of your work together,” Dr. Nelson added.

Although treatment for BPD used to be virtually nonexistent, there is now hope – especially with dialectic-behavior therapy (DBT), which uses mindfulness to teach patients how to control emotions and improve relationships.

According to the National Education Alliance for BPD, other useful treatments include mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy, and “good psychiatric management.” Although there are currently no approved medications for BPD, some drugs are used to treat comorbid conditions such as depression or anxiety.

“We now know that people recover, and the whole paradigm has been turned on its head,” Dr. Nelson said. For example, “we no longer categorize these things as treatable or untreatable, which was a very positive move.”

So why is the field still debating the issue of diagnosis disclosure?

“To this day there are different psychiatrists and some medical school curricula that continue to teach that personality disorders are long-term, fixed, and nontreatable – and that it’s kind of disparaging to give this kind of diagnosis to a patient,” Dr. Nelson said.

Dr. Nelson, also the vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, medical school, reported that there “we acknowledge BPD’s painful history and that there are these misconceptions. They’re going to be on the front line of combating discrimination and the idea that if you see a patient with possible BPD coming you should run. That’s just unacceptable.”

Dr. Nelson noted that the idea of disclosing a BPD diagnosis is less controversial now than in the past, but “the whole thing is still under debate, and treatment guidelines [on BPD] are old and expired.”

Criteria for BPD were not updated when the DSM-5 was published in 2013, and that needs to be fixed, Dr. Nelson added. “In the meantime, we’re trying to get the word out that it’s okay to interact with people about the diagnosis, discuss treatment plans, and manage it as one would with any other psychiatric or medical illness.”

An evolution, not a debate

Paul Appelbaum, MD, past president of the American Psychiatric Association and current chair of the organization’s DSM steering committee, said in an interview that he hasn’t been involved in any recent debate on this issue.

“I think practice has changed to the point where the general practice is to discuss patient diagnoses with [patients] openly. Patients appreciate that and psychiatrists have come to see the advantages of it,” said Dr. Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that patients also increasingly have access to their medical records, “so the reality is that it’s no longer possible in many cases to withhold a diagnosis.”

he said. “Maybe not everyone is entirely on board yet but there has been a sea change in psychiatric practices.”

Asked whether there needs to be some type of guideline update or statement released by the APA regarding BPD, Dr. Appelbaum said he doesn’t think the overall issue is BPD specific but applies to all psychiatric diagnoses.

“To the extent that there are still practitioners today that are telling students or residents [not to disclose], I would guess that they were trained a very long time ago and have not adapted to the new world,” he said.

“I don’t want to speak for the APA, but speaking for myself: I certainly encourage residents that I teach to be open about a diagnosis. It’s not just clinically helpful in some cases, it’s also ethically required from the perspective of allowing patients to make appropriate decisions about their treatment. And arguably it’s legally required as well, as part of the informed consent requirement,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Regarding DSM updates, he noted that the committee “looks to the field to propose to us additions or changes to the DSM that are warranted by data that have been gathered since the DSM-5 came out.” There is a process set up on the DSM’s website to review such proposals.

In addition, Dr. Appelbaum said that there have been discussions about using a new model “that focuses on dimensions rather than on discreet categories” in order to classify personality disorders.

“There’s a group out there that is formulating a proposal that they will submit to us” on this, he added. “That’s the major discussion that is going on right now and it would clearly have implications for borderline as well as all the other personality disorders.”

In a statement, the APA said practice guidelines for BPD are currently under review and that the organization does not have a “position statement” on BPD for clinicians. The last update to its guideline was in the early 2000s.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

News of actor/comedian Pete Davidson expressing relief after finally receiving a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) prompted a recent Twitter discussion among physicians regarding the ongoing debate on whether or not to tell a patient he or she has this diagnosis.

“I’ve heard from [many] trainees that they were told never to tell a patient they had BPD, but I can hardly think of anything more paternalistic and stigmatizing,” Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of community psychiatry at University of California, Davis, tweeted.

“Most patients, when I explain it to them, have this kind of reaction – they feel relieved and understood,” she added.

“I was told that as well [not to tell] in one of my practicum placements,” one respondent who identified herself as a clinical/forensic psychologist tweeted back. “I said it anyway and the person was relieved there was a name for what they were living with.”

However, others disagreed with Dr. Barnhorst, noting that BPD is a very serious, stigmatizing, and challenging disorder to treat and, because of this, may cause patients to lose hope.

Still, Dr. Barnhorst stands by her position. Although “there is a negative stigma against a diagnosis of BPD,” that idea more often comes from the clinician instead of the patient, she said.

“I’ve never had a patient say, ‘how dare you call me that!’ like it was an insult,” she said in an interview. Not disclosing a diagnosis “is like you’re not trusting a patient to be a reasonable adult human about this.”

‘Hard diagnosis’

Although BPD is a “hard diagnosis, we would never withhold a diagnosis of cancer or liver disease or something else we knew patients didn’t want but that we were going to try and treat them for,” said Dr. Barnhorst.

BPD is linked to significant morbidity because of its common association with comorbid conditions, such as major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and dysthymia. A history of self-harm is present in 70%-75% of these patients and some estimates suggest up to 9% of individuals with BPD die by suicide.

In an article published in Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience investigators discussed “ethical and clinical questions psychiatrists should consider” when treating BPD, including whether a diagnosis should be shared with a patient.

After such a diagnosis a patient may “react intensely in negative ways and these responses may be easily triggered,” the researchers wrote.

“A propensity that will likely cause psychiatrists anguish, however, is BPD patients’ increased likelihood of attempting suicide,” they added. Part of the problem has been that, in the past, it was thought that a BPD prognosis was untreatable. However, the researchers note that is no longer the case.

Still, Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, has labeled BPD a so-called “asterisk” disorder.

As she wrote in a recent blog, “We tell patients when they meet criteria for a medical diagnosis.* We show compassion and nonjudgmentalism to patients.* We do not discriminate against patients.*” However, the asterisk for each of these statements is: *Except for those with BPD.

Ongoing debate

Starting around the 1980s, the DSM listed personality disorders under the No. 2 Axis, which is for conditions with symptoms that are “not mitigatable,” said Dr. Nelson.

“It really started as well-meaning therapists who care about their patients who wanted to develop some precision in understanding people, and them starting to notice some patterns that can get in the way of optimal function,” she said in an interview.

The thought was not to disclose these diagnoses “because that was for you to understand, and for the patient to discover these patterns over time in the course of your work together,” Dr. Nelson added.

Although treatment for BPD used to be virtually nonexistent, there is now hope – especially with dialectic-behavior therapy (DBT), which uses mindfulness to teach patients how to control emotions and improve relationships.

According to the National Education Alliance for BPD, other useful treatments include mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy, and “good psychiatric management.” Although there are currently no approved medications for BPD, some drugs are used to treat comorbid conditions such as depression or anxiety.

“We now know that people recover, and the whole paradigm has been turned on its head,” Dr. Nelson said. For example, “we no longer categorize these things as treatable or untreatable, which was a very positive move.”

So why is the field still debating the issue of diagnosis disclosure?

“To this day there are different psychiatrists and some medical school curricula that continue to teach that personality disorders are long-term, fixed, and nontreatable – and that it’s kind of disparaging to give this kind of diagnosis to a patient,” Dr. Nelson said.

Dr. Nelson, also the vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, medical school, reported that there “we acknowledge BPD’s painful history and that there are these misconceptions. They’re going to be on the front line of combating discrimination and the idea that if you see a patient with possible BPD coming you should run. That’s just unacceptable.”

Dr. Nelson noted that the idea of disclosing a BPD diagnosis is less controversial now than in the past, but “the whole thing is still under debate, and treatment guidelines [on BPD] are old and expired.”

Criteria for BPD were not updated when the DSM-5 was published in 2013, and that needs to be fixed, Dr. Nelson added. “In the meantime, we’re trying to get the word out that it’s okay to interact with people about the diagnosis, discuss treatment plans, and manage it as one would with any other psychiatric or medical illness.”

An evolution, not a debate

Paul Appelbaum, MD, past president of the American Psychiatric Association and current chair of the organization’s DSM steering committee, said in an interview that he hasn’t been involved in any recent debate on this issue.

“I think practice has changed to the point where the general practice is to discuss patient diagnoses with [patients] openly. Patients appreciate that and psychiatrists have come to see the advantages of it,” said Dr. Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that patients also increasingly have access to their medical records, “so the reality is that it’s no longer possible in many cases to withhold a diagnosis.”

he said. “Maybe not everyone is entirely on board yet but there has been a sea change in psychiatric practices.”

Asked whether there needs to be some type of guideline update or statement released by the APA regarding BPD, Dr. Appelbaum said he doesn’t think the overall issue is BPD specific but applies to all psychiatric diagnoses.

“To the extent that there are still practitioners today that are telling students or residents [not to disclose], I would guess that they were trained a very long time ago and have not adapted to the new world,” he said.

“I don’t want to speak for the APA, but speaking for myself: I certainly encourage residents that I teach to be open about a diagnosis. It’s not just clinically helpful in some cases, it’s also ethically required from the perspective of allowing patients to make appropriate decisions about their treatment. And arguably it’s legally required as well, as part of the informed consent requirement,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Regarding DSM updates, he noted that the committee “looks to the field to propose to us additions or changes to the DSM that are warranted by data that have been gathered since the DSM-5 came out.” There is a process set up on the DSM’s website to review such proposals.

In addition, Dr. Appelbaum said that there have been discussions about using a new model “that focuses on dimensions rather than on discreet categories” in order to classify personality disorders.

“There’s a group out there that is formulating a proposal that they will submit to us” on this, he added. “That’s the major discussion that is going on right now and it would clearly have implications for borderline as well as all the other personality disorders.”

In a statement, the APA said practice guidelines for BPD are currently under review and that the organization does not have a “position statement” on BPD for clinicians. The last update to its guideline was in the early 2000s.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

News of actor/comedian Pete Davidson expressing relief after finally receiving a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) prompted a recent Twitter discussion among physicians regarding the ongoing debate on whether or not to tell a patient he or she has this diagnosis.

“I’ve heard from [many] trainees that they were told never to tell a patient they had BPD, but I can hardly think of anything more paternalistic and stigmatizing,” Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of community psychiatry at University of California, Davis, tweeted.

“Most patients, when I explain it to them, have this kind of reaction – they feel relieved and understood,” she added.

“I was told that as well [not to tell] in one of my practicum placements,” one respondent who identified herself as a clinical/forensic psychologist tweeted back. “I said it anyway and the person was relieved there was a name for what they were living with.”

However, others disagreed with Dr. Barnhorst, noting that BPD is a very serious, stigmatizing, and challenging disorder to treat and, because of this, may cause patients to lose hope.

Still, Dr. Barnhorst stands by her position. Although “there is a negative stigma against a diagnosis of BPD,” that idea more often comes from the clinician instead of the patient, she said.

“I’ve never had a patient say, ‘how dare you call me that!’ like it was an insult,” she said in an interview. Not disclosing a diagnosis “is like you’re not trusting a patient to be a reasonable adult human about this.”

‘Hard diagnosis’

Although BPD is a “hard diagnosis, we would never withhold a diagnosis of cancer or liver disease or something else we knew patients didn’t want but that we were going to try and treat them for,” said Dr. Barnhorst.

BPD is linked to significant morbidity because of its common association with comorbid conditions, such as major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and dysthymia. A history of self-harm is present in 70%-75% of these patients and some estimates suggest up to 9% of individuals with BPD die by suicide.

In an article published in Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience investigators discussed “ethical and clinical questions psychiatrists should consider” when treating BPD, including whether a diagnosis should be shared with a patient.

After such a diagnosis a patient may “react intensely in negative ways and these responses may be easily triggered,” the researchers wrote.

“A propensity that will likely cause psychiatrists anguish, however, is BPD patients’ increased likelihood of attempting suicide,” they added. Part of the problem has been that, in the past, it was thought that a BPD prognosis was untreatable. However, the researchers note that is no longer the case.

Still, Kaz Nelson, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, has labeled BPD a so-called “asterisk” disorder.

As she wrote in a recent blog, “We tell patients when they meet criteria for a medical diagnosis.* We show compassion and nonjudgmentalism to patients.* We do not discriminate against patients.*” However, the asterisk for each of these statements is: *Except for those with BPD.

Ongoing debate

Starting around the 1980s, the DSM listed personality disorders under the No. 2 Axis, which is for conditions with symptoms that are “not mitigatable,” said Dr. Nelson.

“It really started as well-meaning therapists who care about their patients who wanted to develop some precision in understanding people, and them starting to notice some patterns that can get in the way of optimal function,” she said in an interview.

The thought was not to disclose these diagnoses “because that was for you to understand, and for the patient to discover these patterns over time in the course of your work together,” Dr. Nelson added.

Although treatment for BPD used to be virtually nonexistent, there is now hope – especially with dialectic-behavior therapy (DBT), which uses mindfulness to teach patients how to control emotions and improve relationships.

According to the National Education Alliance for BPD, other useful treatments include mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy, and “good psychiatric management.” Although there are currently no approved medications for BPD, some drugs are used to treat comorbid conditions such as depression or anxiety.

“We now know that people recover, and the whole paradigm has been turned on its head,” Dr. Nelson said. For example, “we no longer categorize these things as treatable or untreatable, which was a very positive move.”

So why is the field still debating the issue of diagnosis disclosure?

“To this day there are different psychiatrists and some medical school curricula that continue to teach that personality disorders are long-term, fixed, and nontreatable – and that it’s kind of disparaging to give this kind of diagnosis to a patient,” Dr. Nelson said.

Dr. Nelson, also the vice chair for education at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, medical school, reported that there “we acknowledge BPD’s painful history and that there are these misconceptions. They’re going to be on the front line of combating discrimination and the idea that if you see a patient with possible BPD coming you should run. That’s just unacceptable.”

Dr. Nelson noted that the idea of disclosing a BPD diagnosis is less controversial now than in the past, but “the whole thing is still under debate, and treatment guidelines [on BPD] are old and expired.”

Criteria for BPD were not updated when the DSM-5 was published in 2013, and that needs to be fixed, Dr. Nelson added. “In the meantime, we’re trying to get the word out that it’s okay to interact with people about the diagnosis, discuss treatment plans, and manage it as one would with any other psychiatric or medical illness.”

An evolution, not a debate

Paul Appelbaum, MD, past president of the American Psychiatric Association and current chair of the organization’s DSM steering committee, said in an interview that he hasn’t been involved in any recent debate on this issue.

“I think practice has changed to the point where the general practice is to discuss patient diagnoses with [patients] openly. Patients appreciate that and psychiatrists have come to see the advantages of it,” said Dr. Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York.

Dr. Appelbaum noted that patients also increasingly have access to their medical records, “so the reality is that it’s no longer possible in many cases to withhold a diagnosis.”

he said. “Maybe not everyone is entirely on board yet but there has been a sea change in psychiatric practices.”

Asked whether there needs to be some type of guideline update or statement released by the APA regarding BPD, Dr. Appelbaum said he doesn’t think the overall issue is BPD specific but applies to all psychiatric diagnoses.

“To the extent that there are still practitioners today that are telling students or residents [not to disclose], I would guess that they were trained a very long time ago and have not adapted to the new world,” he said.

“I don’t want to speak for the APA, but speaking for myself: I certainly encourage residents that I teach to be open about a diagnosis. It’s not just clinically helpful in some cases, it’s also ethically required from the perspective of allowing patients to make appropriate decisions about their treatment. And arguably it’s legally required as well, as part of the informed consent requirement,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Regarding DSM updates, he noted that the committee “looks to the field to propose to us additions or changes to the DSM that are warranted by data that have been gathered since the DSM-5 came out.” There is a process set up on the DSM’s website to review such proposals.

In addition, Dr. Appelbaum said that there have been discussions about using a new model “that focuses on dimensions rather than on discreet categories” in order to classify personality disorders.

“There’s a group out there that is formulating a proposal that they will submit to us” on this, he added. “That’s the major discussion that is going on right now and it would clearly have implications for borderline as well as all the other personality disorders.”

In a statement, the APA said practice guidelines for BPD are currently under review and that the organization does not have a “position statement” on BPD for clinicians. The last update to its guideline was in the early 2000s.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A clinical approach to pharmacotherapy for personality disorders

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

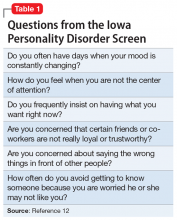

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

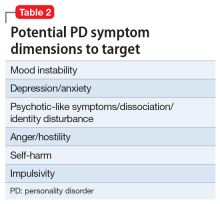

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

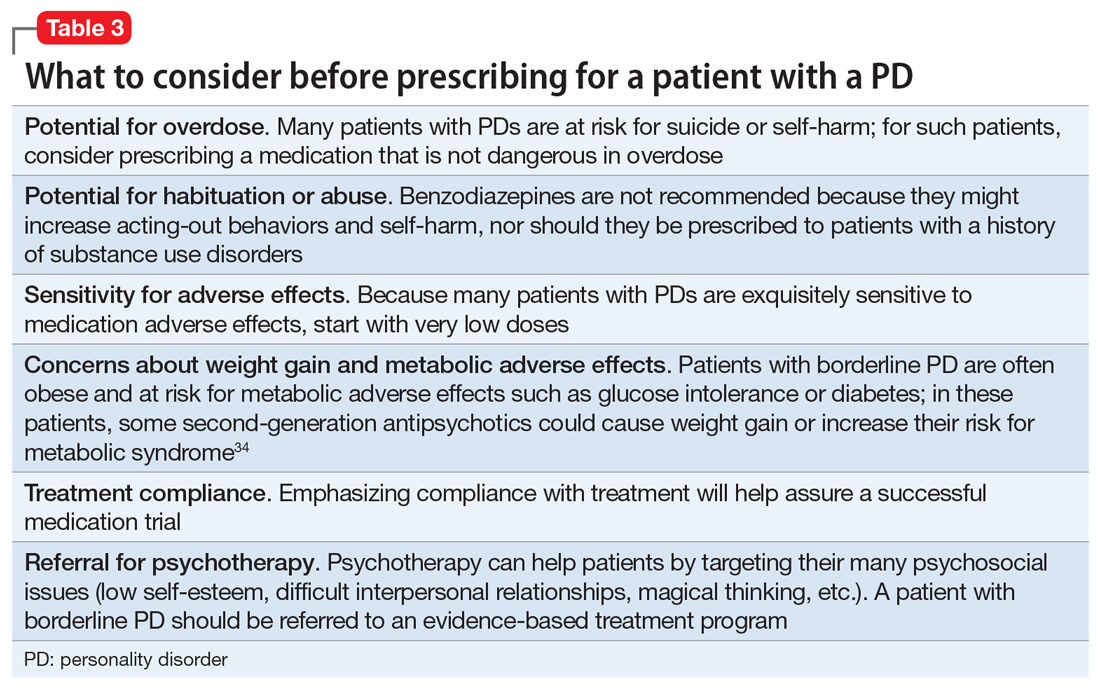

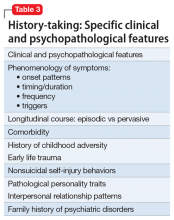

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

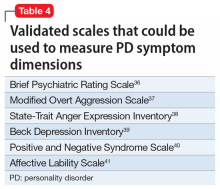

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.

18. Yang Y, Glenn AL, Raine A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: implications for the law. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(1):65-83.

19. Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Choi-Kain LW, et al. Neural correlates of negative emotionality in BPD: an activation-likelihood-estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):153-160.

20. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831.

21. Slutske WS. The genetics of antisocial behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(2):158-162.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1257-1288.

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG78]. Published January 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG77]. Published January 2009. Updated March 27, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77

25. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rep. 2010;(8):CD007667.

26. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(8):CD005652.

27. Black DW. The treatment of antisocial personality disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0123-z

28. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(8):708-713.

29. Ansseau M. The obsessive-compulsive personality: diagnostic aspects and treatment possibilities. In: Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, eds. Focus on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Syn-Thesis; 1997:61-73.

30. Koenigsberg HW, Reynolds D, Goodman M, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of schizotypal personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):628-634.

31. Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A, et al. Comparison of low and moderate dosages of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1174-1182.

32. Nickel MK, Muelbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):833-838.

33. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764.

34. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12)1660-1665.

35. Cowdry RW, Gardner DL. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Alprazolam, carbamazepine, trifluoperazine, and tranylcypromine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(2):111-119.

36. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799-812.

37. Ratey JJ, Gutheil CM. The measurement of aggressive behavior: reflections on the use of the Overt Aggression Scale and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S57-S60.

38. Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: Maruish ME, ed. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999:993-1021.

39. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory II. Psychological Corp; 1996.

40. Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form. The University of Iowa; 1999.

41. Harvey D, Greenberg BR, Serper MR, et al. The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(5):786-793.

42. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Person Disord. 2003:17(3):233-242.

43. Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a new scale to measure severity and change in borderline personality disorder. J Person Disord. 2009;23(3):281-293.

44. Ahearn EP. The use of visual analog scales in mood disorders: a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(5):569-579.

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

What to do before prescribing

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.

18. Yang Y, Glenn AL, Raine A. Brain abnormalities in antisocial individuals: implications for the law. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26(1):65-83.

19. Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Choi-Kain LW, et al. Neural correlates of negative emotionality in BPD: an activation-likelihood-estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):153-160.

20. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831.

21. Slutske WS. The genetics of antisocial behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(2):158-162.

22. Ripoll LH, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1257-1288.

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG78]. Published January 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG77]. Published January 2009. Updated March 27, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg77

25. Khalifa N, Duggan C, Stoffers J, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rep. 2010;(8):CD007667.

26. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(8):CD005652.

27. Black DW. The treatment of antisocial personality disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-017-0123-z

28. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, et al. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(8):708-713.

29. Ansseau M. The obsessive-compulsive personality: diagnostic aspects and treatment possibilities. In: Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, eds. Focus on obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Syn-Thesis; 1997:61-73.