User login

Implementing a critical care TEE program at your institution

Starting from the ground up!

Bedside-focused cardiac ultrasound assessment, or cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), has become common in intensive care units throughout the US and the world.

However, obtaining images adequate for decision making via standard transthoracic echo (TTE) is not possible in a significant number of patients; as high as 30% of critically ill patients, according to The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines.1 Factors common to critically ill patients, such as invasive mechanical ventilation, external dressings, and limited mobility, contribute to poor image acquisition.

In almost all these cases, the factors limiting image acquisition can be eliminated by utilizing a transesophageal approach. In a recent study, researchers were able to demonstrate that adding transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to TTE in critically ill patients yielded a new diagnosis or a change in management about 45% of the time.2

Using transesophageal ultrasound for a focused cardiac assessment in hemodynamically unstable patients is not new—and is often referred to as rescue TEE or resuscitative TEE. A broader term, transesophageal ultrasound, has also been used to include sonographic evaluation of the lungs in patients with poor acoustic windows. At my institution, we use the term critical care TEE to define TEE performed by a noncardiology-trained intensivist in an intubated critically ill patient.

Regardless of the term, the use of transesophageal ultrasound by the noncardiologist in the ICU appears to be a developing trend. As with other uses of POCUS, ultrasound machines continue to be able to “do more” at a lower price point. In 2024, several cart-based ultrasound machines are compatible with transesophageal probes and contain software packages capable of common cardiac measurements.

Despite this growing interest, intensivists are likely to encounter barriers to implementing critical care TEE. Our division recently implemented adding TEE to our practice. Our practice involves two separate systems: a Veterans Administration hospital and a university-based county hospital. Our division has integrated the use of TEE in the medical ICU at both institutions. Having navigated the process at both institutions, I can offer some guidance in navigating barriers.

The development of a critical care TEE program must start with a strong base in transthoracic cardiac POCUS, at least for the foreseeable future. Having a strong background in TTE gives learners a solid foundation in cardiac anatomy, cardiac function, and ultrasound properties. Obtaining testamur status or board certification in critical care echocardiography is not an absolute must but is a definite benefit. Having significant experience in TTE image acquisition and interpretation will flatten the learning curve for TEE. Interestingly, image acquisition in TEE is often easier than in TTE, so the paradigm of learning TTE before TEE may reverse in the years to come.

Two barriers often work together to create a vicious cycle that stops the development of a TEE program at its start. These barriers include the lack of training and lack of equipment, specifically a TEE probe. Those who do not understand the value of TEE may ask, “Why purchase equipment for a procedure that you do not yet know how to do?” The opposite question can also be asked, “Why get trained to do something you don’t have the equipment to perform?”

My best advice to break this cycle is to “dive in” to whichever barrier seems easier to overcome first. I started with obtaining knowledge and training. Obtaining training and education in a procedure that is historically not done in your specialty is challenging but is not impossible. It takes a combination of high levels of self-motivation and at least one colleague with the training to support you. I approached a cardiac anesthesiologist, whom I knew from the surgical ICU. Cardiologists can also be a resource, but working with cardiac anesthesiologists offers several advantages. TEEs done by cardiac anesthesiologists are similar to those done in ICU patients (ie, all patients are intubated and sedated). The procedures are also scheduled several days in advance, making it easier to integrate training into your daily work schedule. Lastly, the TEE probe remains in place for several hours, so repeating the probe manipulations again as a learner does not add additional risk to the patient. In my case, we somewhat arbitrarily agreed that I participate in 25 TEE exams. (CME courses, both online and in-person simulation, exist and greatly supplement self-study.)

Obtaining equipment is also a common barrier, though this has become less restrictive in the last several years. As previously mentioned, many cart-based ultrasound machines can accommodate a TEE probe. This changes the request from purchasing a new machine to “just a probe.” Despite the higher cost than most other probes, those in charge of purchasing are often more open to purchasing “a probe” than to purchasing an ultrasound machine.

Additionally, the purchasing decision regarding probes may fall to a different person than it does for an ultrasound machine. If available, POCUS image archiving into the medical record can help offset the cost of equipment, both by increasing revenue via billing and by demonstrating that equipment is being used. If initially declined, continue to ask and work to integrate the purchase into the next year’s budget. Inquire about the process of making a formal request and follow that process. This will often involve obtaining a quote or quotes from the ultrasound manufacturer(s).

Keep in mind that the probe will require a special storage cabinet specifically designed for TEE probes. It is prudent to include this in budget requests. If needed, the echocardiography lab can be a useful resource for additional information regarding the cabinet requirements. It is strongly recommended to discuss TEE probe models with sterile processing before any purchasing. If options are available, it is wise to choose a model the hospital already uses, as the cleaning protocol is well established. Our unit purchased a model that did not have an established protocol, which took nearly 6 months to develop. If probe options are limited, involving sterile processing early to start developing a protocol will help decrease delays.

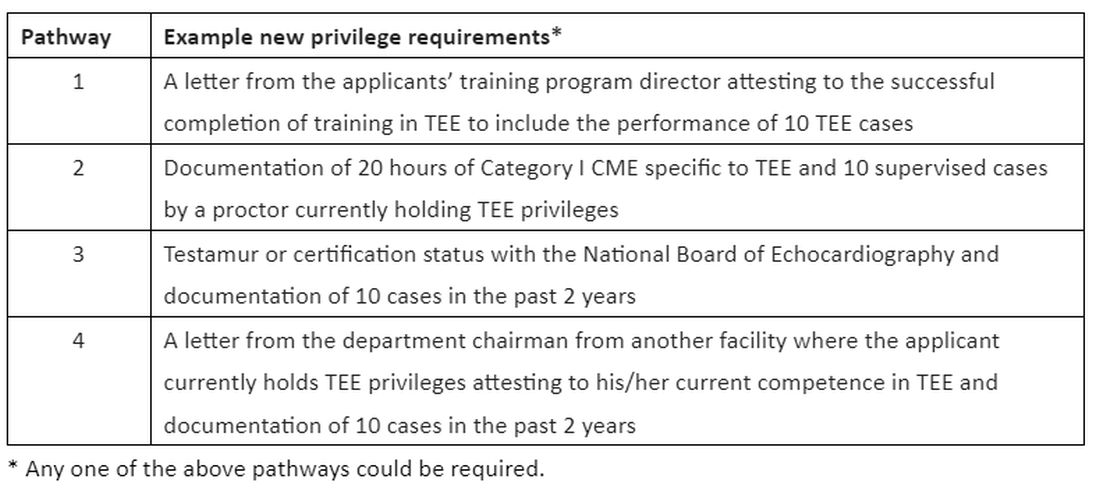

Obtaining hospital privileges is also a common barrier, though this may not be as challenging as expected. Hospitals typically have well-outlined policies on obtaining privileges for established procedures. One of our hospital systems had four different options; the most straightforward required 20 hours of CME specific to TEE and 10 supervised cases by a proctor currently holding TEE privileges (see Table 1).

Discussions about obtaining privileges should involve your division chief, chair of medicine, and the cardiology division chief. Clearly outlining the plan to perform this procedure only in critically ill patients who are already intubated for other reasons made these conversations go much more smoothly. In the development of delineation of privileges, we used the term critical care TEE to clearly define this patient population. During these conversations, highlight the safety of the procedure; ASE guidelines3 estimate a severe complication rate of less than 1 in 10,000 cases and explain the anticipated benefits to critically ill patients.

In conclusion, at an institution that is already adept at the use of POCUS in the ICU, the additional of critical care TEE within 1 to 2 years is a very realistic achievement. It will undoubtedly require patience, persistence, and self-motivation, but the barriers are becoming smaller every day. Stay motivated!

Dr. Proud is Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Director, UT Health San Antonio.

References:

1. Porter TR, Abdelmoneim S, Belcik FT, et al. Guidelines for the cardiac sonographer in the performance of contrast echocardiography: a focused update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;27(8):797-810.

2. Si X, Ma J, Cao DY, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography instead or in addition to transthoracic echocardiography in evaluating haemodynamic problems in intubated critically ill patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(12):785.

3. Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, et al. Guidelines for performing a cmprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardioraphy and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(9):921-964.

Starting from the ground up!

Starting from the ground up!

Bedside-focused cardiac ultrasound assessment, or cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), has become common in intensive care units throughout the US and the world.

However, obtaining images adequate for decision making via standard transthoracic echo (TTE) is not possible in a significant number of patients; as high as 30% of critically ill patients, according to The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines.1 Factors common to critically ill patients, such as invasive mechanical ventilation, external dressings, and limited mobility, contribute to poor image acquisition.

In almost all these cases, the factors limiting image acquisition can be eliminated by utilizing a transesophageal approach. In a recent study, researchers were able to demonstrate that adding transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to TTE in critically ill patients yielded a new diagnosis or a change in management about 45% of the time.2

Using transesophageal ultrasound for a focused cardiac assessment in hemodynamically unstable patients is not new—and is often referred to as rescue TEE or resuscitative TEE. A broader term, transesophageal ultrasound, has also been used to include sonographic evaluation of the lungs in patients with poor acoustic windows. At my institution, we use the term critical care TEE to define TEE performed by a noncardiology-trained intensivist in an intubated critically ill patient.

Regardless of the term, the use of transesophageal ultrasound by the noncardiologist in the ICU appears to be a developing trend. As with other uses of POCUS, ultrasound machines continue to be able to “do more” at a lower price point. In 2024, several cart-based ultrasound machines are compatible with transesophageal probes and contain software packages capable of common cardiac measurements.

Despite this growing interest, intensivists are likely to encounter barriers to implementing critical care TEE. Our division recently implemented adding TEE to our practice. Our practice involves two separate systems: a Veterans Administration hospital and a university-based county hospital. Our division has integrated the use of TEE in the medical ICU at both institutions. Having navigated the process at both institutions, I can offer some guidance in navigating barriers.

The development of a critical care TEE program must start with a strong base in transthoracic cardiac POCUS, at least for the foreseeable future. Having a strong background in TTE gives learners a solid foundation in cardiac anatomy, cardiac function, and ultrasound properties. Obtaining testamur status or board certification in critical care echocardiography is not an absolute must but is a definite benefit. Having significant experience in TTE image acquisition and interpretation will flatten the learning curve for TEE. Interestingly, image acquisition in TEE is often easier than in TTE, so the paradigm of learning TTE before TEE may reverse in the years to come.

Two barriers often work together to create a vicious cycle that stops the development of a TEE program at its start. These barriers include the lack of training and lack of equipment, specifically a TEE probe. Those who do not understand the value of TEE may ask, “Why purchase equipment for a procedure that you do not yet know how to do?” The opposite question can also be asked, “Why get trained to do something you don’t have the equipment to perform?”

My best advice to break this cycle is to “dive in” to whichever barrier seems easier to overcome first. I started with obtaining knowledge and training. Obtaining training and education in a procedure that is historically not done in your specialty is challenging but is not impossible. It takes a combination of high levels of self-motivation and at least one colleague with the training to support you. I approached a cardiac anesthesiologist, whom I knew from the surgical ICU. Cardiologists can also be a resource, but working with cardiac anesthesiologists offers several advantages. TEEs done by cardiac anesthesiologists are similar to those done in ICU patients (ie, all patients are intubated and sedated). The procedures are also scheduled several days in advance, making it easier to integrate training into your daily work schedule. Lastly, the TEE probe remains in place for several hours, so repeating the probe manipulations again as a learner does not add additional risk to the patient. In my case, we somewhat arbitrarily agreed that I participate in 25 TEE exams. (CME courses, both online and in-person simulation, exist and greatly supplement self-study.)

Obtaining equipment is also a common barrier, though this has become less restrictive in the last several years. As previously mentioned, many cart-based ultrasound machines can accommodate a TEE probe. This changes the request from purchasing a new machine to “just a probe.” Despite the higher cost than most other probes, those in charge of purchasing are often more open to purchasing “a probe” than to purchasing an ultrasound machine.

Additionally, the purchasing decision regarding probes may fall to a different person than it does for an ultrasound machine. If available, POCUS image archiving into the medical record can help offset the cost of equipment, both by increasing revenue via billing and by demonstrating that equipment is being used. If initially declined, continue to ask and work to integrate the purchase into the next year’s budget. Inquire about the process of making a formal request and follow that process. This will often involve obtaining a quote or quotes from the ultrasound manufacturer(s).

Keep in mind that the probe will require a special storage cabinet specifically designed for TEE probes. It is prudent to include this in budget requests. If needed, the echocardiography lab can be a useful resource for additional information regarding the cabinet requirements. It is strongly recommended to discuss TEE probe models with sterile processing before any purchasing. If options are available, it is wise to choose a model the hospital already uses, as the cleaning protocol is well established. Our unit purchased a model that did not have an established protocol, which took nearly 6 months to develop. If probe options are limited, involving sterile processing early to start developing a protocol will help decrease delays.

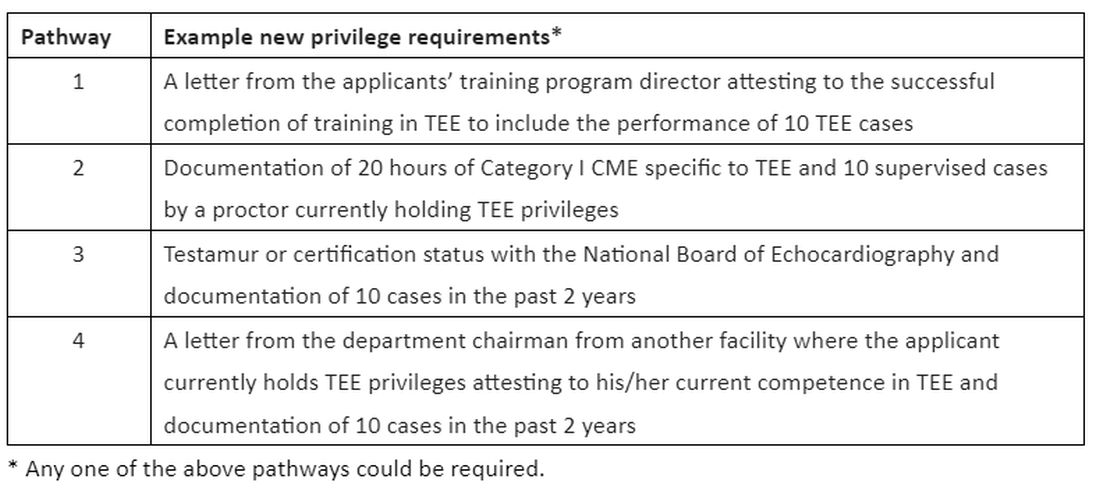

Obtaining hospital privileges is also a common barrier, though this may not be as challenging as expected. Hospitals typically have well-outlined policies on obtaining privileges for established procedures. One of our hospital systems had four different options; the most straightforward required 20 hours of CME specific to TEE and 10 supervised cases by a proctor currently holding TEE privileges (see Table 1).

Discussions about obtaining privileges should involve your division chief, chair of medicine, and the cardiology division chief. Clearly outlining the plan to perform this procedure only in critically ill patients who are already intubated for other reasons made these conversations go much more smoothly. In the development of delineation of privileges, we used the term critical care TEE to clearly define this patient population. During these conversations, highlight the safety of the procedure; ASE guidelines3 estimate a severe complication rate of less than 1 in 10,000 cases and explain the anticipated benefits to critically ill patients.

In conclusion, at an institution that is already adept at the use of POCUS in the ICU, the additional of critical care TEE within 1 to 2 years is a very realistic achievement. It will undoubtedly require patience, persistence, and self-motivation, but the barriers are becoming smaller every day. Stay motivated!

Dr. Proud is Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Director, UT Health San Antonio.

References:

1. Porter TR, Abdelmoneim S, Belcik FT, et al. Guidelines for the cardiac sonographer in the performance of contrast echocardiography: a focused update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;27(8):797-810.

2. Si X, Ma J, Cao DY, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography instead or in addition to transthoracic echocardiography in evaluating haemodynamic problems in intubated critically ill patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(12):785.

3. Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, et al. Guidelines for performing a cmprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardioraphy and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(9):921-964.

Bedside-focused cardiac ultrasound assessment, or cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), has become common in intensive care units throughout the US and the world.

However, obtaining images adequate for decision making via standard transthoracic echo (TTE) is not possible in a significant number of patients; as high as 30% of critically ill patients, according to The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines.1 Factors common to critically ill patients, such as invasive mechanical ventilation, external dressings, and limited mobility, contribute to poor image acquisition.

In almost all these cases, the factors limiting image acquisition can be eliminated by utilizing a transesophageal approach. In a recent study, researchers were able to demonstrate that adding transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to TTE in critically ill patients yielded a new diagnosis or a change in management about 45% of the time.2

Using transesophageal ultrasound for a focused cardiac assessment in hemodynamically unstable patients is not new—and is often referred to as rescue TEE or resuscitative TEE. A broader term, transesophageal ultrasound, has also been used to include sonographic evaluation of the lungs in patients with poor acoustic windows. At my institution, we use the term critical care TEE to define TEE performed by a noncardiology-trained intensivist in an intubated critically ill patient.

Regardless of the term, the use of transesophageal ultrasound by the noncardiologist in the ICU appears to be a developing trend. As with other uses of POCUS, ultrasound machines continue to be able to “do more” at a lower price point. In 2024, several cart-based ultrasound machines are compatible with transesophageal probes and contain software packages capable of common cardiac measurements.

Despite this growing interest, intensivists are likely to encounter barriers to implementing critical care TEE. Our division recently implemented adding TEE to our practice. Our practice involves two separate systems: a Veterans Administration hospital and a university-based county hospital. Our division has integrated the use of TEE in the medical ICU at both institutions. Having navigated the process at both institutions, I can offer some guidance in navigating barriers.

The development of a critical care TEE program must start with a strong base in transthoracic cardiac POCUS, at least for the foreseeable future. Having a strong background in TTE gives learners a solid foundation in cardiac anatomy, cardiac function, and ultrasound properties. Obtaining testamur status or board certification in critical care echocardiography is not an absolute must but is a definite benefit. Having significant experience in TTE image acquisition and interpretation will flatten the learning curve for TEE. Interestingly, image acquisition in TEE is often easier than in TTE, so the paradigm of learning TTE before TEE may reverse in the years to come.

Two barriers often work together to create a vicious cycle that stops the development of a TEE program at its start. These barriers include the lack of training and lack of equipment, specifically a TEE probe. Those who do not understand the value of TEE may ask, “Why purchase equipment for a procedure that you do not yet know how to do?” The opposite question can also be asked, “Why get trained to do something you don’t have the equipment to perform?”

My best advice to break this cycle is to “dive in” to whichever barrier seems easier to overcome first. I started with obtaining knowledge and training. Obtaining training and education in a procedure that is historically not done in your specialty is challenging but is not impossible. It takes a combination of high levels of self-motivation and at least one colleague with the training to support you. I approached a cardiac anesthesiologist, whom I knew from the surgical ICU. Cardiologists can also be a resource, but working with cardiac anesthesiologists offers several advantages. TEEs done by cardiac anesthesiologists are similar to those done in ICU patients (ie, all patients are intubated and sedated). The procedures are also scheduled several days in advance, making it easier to integrate training into your daily work schedule. Lastly, the TEE probe remains in place for several hours, so repeating the probe manipulations again as a learner does not add additional risk to the patient. In my case, we somewhat arbitrarily agreed that I participate in 25 TEE exams. (CME courses, both online and in-person simulation, exist and greatly supplement self-study.)

Obtaining equipment is also a common barrier, though this has become less restrictive in the last several years. As previously mentioned, many cart-based ultrasound machines can accommodate a TEE probe. This changes the request from purchasing a new machine to “just a probe.” Despite the higher cost than most other probes, those in charge of purchasing are often more open to purchasing “a probe” than to purchasing an ultrasound machine.

Additionally, the purchasing decision regarding probes may fall to a different person than it does for an ultrasound machine. If available, POCUS image archiving into the medical record can help offset the cost of equipment, both by increasing revenue via billing and by demonstrating that equipment is being used. If initially declined, continue to ask and work to integrate the purchase into the next year’s budget. Inquire about the process of making a formal request and follow that process. This will often involve obtaining a quote or quotes from the ultrasound manufacturer(s).

Keep in mind that the probe will require a special storage cabinet specifically designed for TEE probes. It is prudent to include this in budget requests. If needed, the echocardiography lab can be a useful resource for additional information regarding the cabinet requirements. It is strongly recommended to discuss TEE probe models with sterile processing before any purchasing. If options are available, it is wise to choose a model the hospital already uses, as the cleaning protocol is well established. Our unit purchased a model that did not have an established protocol, which took nearly 6 months to develop. If probe options are limited, involving sterile processing early to start developing a protocol will help decrease delays.

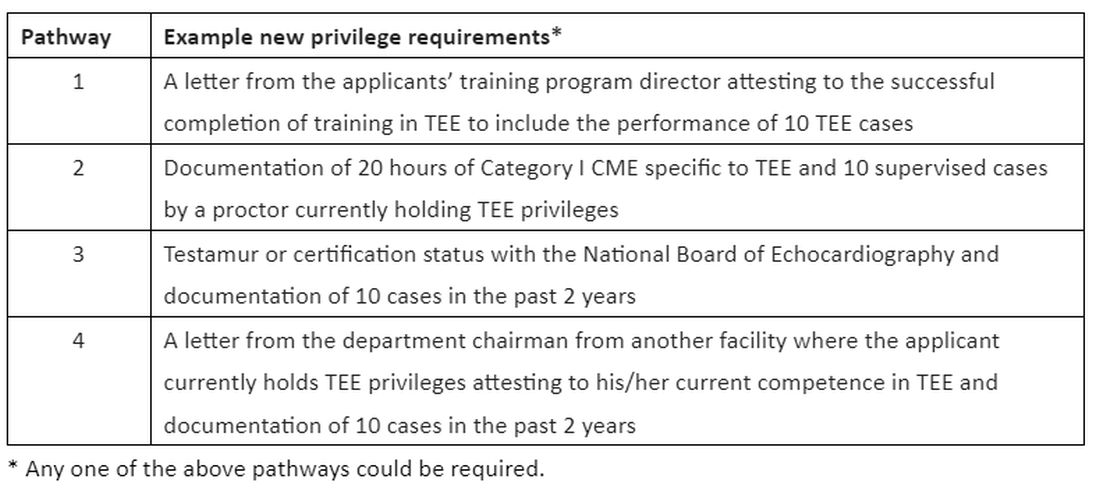

Obtaining hospital privileges is also a common barrier, though this may not be as challenging as expected. Hospitals typically have well-outlined policies on obtaining privileges for established procedures. One of our hospital systems had four different options; the most straightforward required 20 hours of CME specific to TEE and 10 supervised cases by a proctor currently holding TEE privileges (see Table 1).

Discussions about obtaining privileges should involve your division chief, chair of medicine, and the cardiology division chief. Clearly outlining the plan to perform this procedure only in critically ill patients who are already intubated for other reasons made these conversations go much more smoothly. In the development of delineation of privileges, we used the term critical care TEE to clearly define this patient population. During these conversations, highlight the safety of the procedure; ASE guidelines3 estimate a severe complication rate of less than 1 in 10,000 cases and explain the anticipated benefits to critically ill patients.

In conclusion, at an institution that is already adept at the use of POCUS in the ICU, the additional of critical care TEE within 1 to 2 years is a very realistic achievement. It will undoubtedly require patience, persistence, and self-motivation, but the barriers are becoming smaller every day. Stay motivated!

Dr. Proud is Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Director, UT Health San Antonio.

References:

1. Porter TR, Abdelmoneim S, Belcik FT, et al. Guidelines for the cardiac sonographer in the performance of contrast echocardiography: a focused update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;27(8):797-810.

2. Si X, Ma J, Cao DY, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography instead or in addition to transthoracic echocardiography in evaluating haemodynamic problems in intubated critically ill patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(12):785.

3. Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, et al. Guidelines for performing a cmprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardioraphy and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(9):921-964.

Daylight Saving Time: Saving light but endangering health

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently published its position statement reaffirming its support of utilizing permanent Standard Time (ST) as opposed to Daylight Saving Time (DST).1 DST usually occurs on the second Sunday in March when we “spring forward” by advancing the clock by 1 hour. The analogous “fall back” on the first Sunday in November refers to reversion back to the original ST, which is more synchronous with the sun’s natural pattern of rise and fall.

The earliest argument for DST practice dates back to the 1700s when Benjamin Franklin wrote a satirical piece in the Journal of Paris suggesting that advancing the clock to rise earlier in the summer would lead to economization in candle usage and save significant resources for Parisians. The modern version of this assertion infers that increased daylight in the evening will lead to increased consumer activity and work productivity with consequent economic benefits. Interestingly, the adoption of DST has demonstrated the opposite—a reduction in work productivity and economic losses.2 Another often-cited claim is that increased daylight in the evening could lead to fewer motor vehicle accidents. However, the reality is that DST is associated with more frequent car accidents in the morning.

The greatest drawback of DST is that, initially, it leads to sleep deprivation and chronically drives asynchronization between the circadian clock and the social clock. Humans synchronize their internal clock based on several factors, including light, temperature, feeding, and social habits. However, light is the strongest exogenous factor that regulates the internal clock. Light inhibits secretion of melatonin, an endogenous hormone that promotes sleep onset. While there is some individual variation in circadian patterns, exposure to bright light in the morning leads to increased physical, mental, and goal-directed activity.

Conversely, darkness or reduced light exposure in the evening hours promotes decreased activity and sleep onset via melatonin release. DST disrupts this natural process by promoting increased light exposure in the evening. This desynchronizes solar light from our internal clocks, causing a relative phase delay. Acutely, patients experience a form of imposed social jet lag. They lose an hour of sleep due to diminished sleep opportunity, as work and social obligations are typically not altered to allow for a later awakening. With recurrent delays, this lends to a pattern of chronic sleep deprivation which has significant health consequences.

Losing an hour of sleep opportunity as the clock advances in spring has dire consequences. The transition to DST is associated with increased cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and admissions for acute atrial fibrillation.3 4 5 A large body of work has shown that acute reduction of sleep is associated with higher sympathetic tone, compromised immunity, and increased inflammation. Further, cognitive consequences can ensue in the form of altered situational awareness, increased risky behavior, and worse reaction time—which manifest as increased motor vehicle accidents, injuries, and fatalities.6 Emergency room visits and bounce-back admissions, medical errors and injuries, and missed appointments increase following the switch to DST.7 Psychiatric outcomes, including deaths due to suicide and overdose, are worse with the spring transition.8

Is the problem with DST merely limited to springtime, when we lose an hour of sleep? Not quite. During the “fall back” period, despite theoretically gaining an hour of sleep opportunity, people exhibit evidence of sleep disruption, psychiatric issues, traffic accidents, and inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations. These consequences likely stem from a discordance between circadian and social time, which leads to an earlier awakening based on circadian physiology as opposed to the clock time.

The acute impact of changing our sleep patterns during transitions in clock time may be appreciated more readily, but the damage is much more insidious. Chronic exposure to light in the late evening creates a state of enhanced arousal when the body should be winding down. The chronic incongruency between clock and solar time leads to dyssynchrony in our usual functions, such as food intake, social and physical activity, and basal temperature. Consequently, there is an impetus to fall asleep later. This leads to an accumulation of sleep debt and its associated negative consequences in the general, already chronically sleep-deprived population. This is especially impactful to adolescents and young adults who tend to have a delay in their sleep and wake patterns and, yet, are socially bound to early morning awakenings for school or work.

The scientific evidence behind the health risk and benefit profile of DST and ST is incontrovertible and in favor of ST. The hallmark of appropriate sleep habits involves consistency and appropriate duration. Changing timing forward or backward increases the likelihood of an alteration of the baseline established sleep and circadian consistency.

Unfortunately, despite multiple polls demonstrating the populace’s dislike of DST, repeat attempts to codify DST and negate ST persist. The latest initiative, the Sunshine Protection Act, which promised permanent DST, was passed by the US Senate but was thankfully foiled by Congress in 2022. The act of setting a time is not one that should be taken lightly or in isolation because there are significant, long-lasting health, safety, and socioeconomic consequences of this decision. Practically, this entails a concerted effort from all major economies since consistency is essential for trade and geopolitical relations. China, Japan, and India don’t practice DST. The European Parliament voted successfully to abolish DST in the European Union in 2019 with a plan to implement ST in 2021. Implementation has yet to be successful due to interruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the current economic and political climate in Europe. Political or theoretical political victories should not supersede the health and safety of an elected official’s constituents. As a medical community, we should continue to use our collective voice to encourage our representatives to vote in ways that positively affect our patients’ health outcomes.

References:

1. Rishi MA, et al. JCSM. 2024;20(1):121.

2. Gibson M, et al. Rev Econ Stat. 2018;100(5):783.

3. Jansky I, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1966.

4. Sipilia J, et al. Sleep Med. 2016;27-28:20.

5. Chudow JJ, et al. Sleep Med. 2020;69:155.

6. Fritz J, et al. Curr Biol. 2020;30(4):729.

7. Ferrazzi E, et al. J Biol Rhythms. 2018;33(5):555-564.

8. Berk M, et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2008;6(1):22.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently published its position statement reaffirming its support of utilizing permanent Standard Time (ST) as opposed to Daylight Saving Time (DST).1 DST usually occurs on the second Sunday in March when we “spring forward” by advancing the clock by 1 hour. The analogous “fall back” on the first Sunday in November refers to reversion back to the original ST, which is more synchronous with the sun’s natural pattern of rise and fall.

The earliest argument for DST practice dates back to the 1700s when Benjamin Franklin wrote a satirical piece in the Journal of Paris suggesting that advancing the clock to rise earlier in the summer would lead to economization in candle usage and save significant resources for Parisians. The modern version of this assertion infers that increased daylight in the evening will lead to increased consumer activity and work productivity with consequent economic benefits. Interestingly, the adoption of DST has demonstrated the opposite—a reduction in work productivity and economic losses.2 Another often-cited claim is that increased daylight in the evening could lead to fewer motor vehicle accidents. However, the reality is that DST is associated with more frequent car accidents in the morning.

The greatest drawback of DST is that, initially, it leads to sleep deprivation and chronically drives asynchronization between the circadian clock and the social clock. Humans synchronize their internal clock based on several factors, including light, temperature, feeding, and social habits. However, light is the strongest exogenous factor that regulates the internal clock. Light inhibits secretion of melatonin, an endogenous hormone that promotes sleep onset. While there is some individual variation in circadian patterns, exposure to bright light in the morning leads to increased physical, mental, and goal-directed activity.

Conversely, darkness or reduced light exposure in the evening hours promotes decreased activity and sleep onset via melatonin release. DST disrupts this natural process by promoting increased light exposure in the evening. This desynchronizes solar light from our internal clocks, causing a relative phase delay. Acutely, patients experience a form of imposed social jet lag. They lose an hour of sleep due to diminished sleep opportunity, as work and social obligations are typically not altered to allow for a later awakening. With recurrent delays, this lends to a pattern of chronic sleep deprivation which has significant health consequences.

Losing an hour of sleep opportunity as the clock advances in spring has dire consequences. The transition to DST is associated with increased cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and admissions for acute atrial fibrillation.3 4 5 A large body of work has shown that acute reduction of sleep is associated with higher sympathetic tone, compromised immunity, and increased inflammation. Further, cognitive consequences can ensue in the form of altered situational awareness, increased risky behavior, and worse reaction time—which manifest as increased motor vehicle accidents, injuries, and fatalities.6 Emergency room visits and bounce-back admissions, medical errors and injuries, and missed appointments increase following the switch to DST.7 Psychiatric outcomes, including deaths due to suicide and overdose, are worse with the spring transition.8

Is the problem with DST merely limited to springtime, when we lose an hour of sleep? Not quite. During the “fall back” period, despite theoretically gaining an hour of sleep opportunity, people exhibit evidence of sleep disruption, psychiatric issues, traffic accidents, and inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations. These consequences likely stem from a discordance between circadian and social time, which leads to an earlier awakening based on circadian physiology as opposed to the clock time.

The acute impact of changing our sleep patterns during transitions in clock time may be appreciated more readily, but the damage is much more insidious. Chronic exposure to light in the late evening creates a state of enhanced arousal when the body should be winding down. The chronic incongruency between clock and solar time leads to dyssynchrony in our usual functions, such as food intake, social and physical activity, and basal temperature. Consequently, there is an impetus to fall asleep later. This leads to an accumulation of sleep debt and its associated negative consequences in the general, already chronically sleep-deprived population. This is especially impactful to adolescents and young adults who tend to have a delay in their sleep and wake patterns and, yet, are socially bound to early morning awakenings for school or work.

The scientific evidence behind the health risk and benefit profile of DST and ST is incontrovertible and in favor of ST. The hallmark of appropriate sleep habits involves consistency and appropriate duration. Changing timing forward or backward increases the likelihood of an alteration of the baseline established sleep and circadian consistency.

Unfortunately, despite multiple polls demonstrating the populace’s dislike of DST, repeat attempts to codify DST and negate ST persist. The latest initiative, the Sunshine Protection Act, which promised permanent DST, was passed by the US Senate but was thankfully foiled by Congress in 2022. The act of setting a time is not one that should be taken lightly or in isolation because there are significant, long-lasting health, safety, and socioeconomic consequences of this decision. Practically, this entails a concerted effort from all major economies since consistency is essential for trade and geopolitical relations. China, Japan, and India don’t practice DST. The European Parliament voted successfully to abolish DST in the European Union in 2019 with a plan to implement ST in 2021. Implementation has yet to be successful due to interruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the current economic and political climate in Europe. Political or theoretical political victories should not supersede the health and safety of an elected official’s constituents. As a medical community, we should continue to use our collective voice to encourage our representatives to vote in ways that positively affect our patients’ health outcomes.

References:

1. Rishi MA, et al. JCSM. 2024;20(1):121.

2. Gibson M, et al. Rev Econ Stat. 2018;100(5):783.

3. Jansky I, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1966.

4. Sipilia J, et al. Sleep Med. 2016;27-28:20.

5. Chudow JJ, et al. Sleep Med. 2020;69:155.

6. Fritz J, et al. Curr Biol. 2020;30(4):729.

7. Ferrazzi E, et al. J Biol Rhythms. 2018;33(5):555-564.

8. Berk M, et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2008;6(1):22.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently published its position statement reaffirming its support of utilizing permanent Standard Time (ST) as opposed to Daylight Saving Time (DST).1 DST usually occurs on the second Sunday in March when we “spring forward” by advancing the clock by 1 hour. The analogous “fall back” on the first Sunday in November refers to reversion back to the original ST, which is more synchronous with the sun’s natural pattern of rise and fall.

The earliest argument for DST practice dates back to the 1700s when Benjamin Franklin wrote a satirical piece in the Journal of Paris suggesting that advancing the clock to rise earlier in the summer would lead to economization in candle usage and save significant resources for Parisians. The modern version of this assertion infers that increased daylight in the evening will lead to increased consumer activity and work productivity with consequent economic benefits. Interestingly, the adoption of DST has demonstrated the opposite—a reduction in work productivity and economic losses.2 Another often-cited claim is that increased daylight in the evening could lead to fewer motor vehicle accidents. However, the reality is that DST is associated with more frequent car accidents in the morning.

The greatest drawback of DST is that, initially, it leads to sleep deprivation and chronically drives asynchronization between the circadian clock and the social clock. Humans synchronize their internal clock based on several factors, including light, temperature, feeding, and social habits. However, light is the strongest exogenous factor that regulates the internal clock. Light inhibits secretion of melatonin, an endogenous hormone that promotes sleep onset. While there is some individual variation in circadian patterns, exposure to bright light in the morning leads to increased physical, mental, and goal-directed activity.

Conversely, darkness or reduced light exposure in the evening hours promotes decreased activity and sleep onset via melatonin release. DST disrupts this natural process by promoting increased light exposure in the evening. This desynchronizes solar light from our internal clocks, causing a relative phase delay. Acutely, patients experience a form of imposed social jet lag. They lose an hour of sleep due to diminished sleep opportunity, as work and social obligations are typically not altered to allow for a later awakening. With recurrent delays, this lends to a pattern of chronic sleep deprivation which has significant health consequences.

Losing an hour of sleep opportunity as the clock advances in spring has dire consequences. The transition to DST is associated with increased cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and admissions for acute atrial fibrillation.3 4 5 A large body of work has shown that acute reduction of sleep is associated with higher sympathetic tone, compromised immunity, and increased inflammation. Further, cognitive consequences can ensue in the form of altered situational awareness, increased risky behavior, and worse reaction time—which manifest as increased motor vehicle accidents, injuries, and fatalities.6 Emergency room visits and bounce-back admissions, medical errors and injuries, and missed appointments increase following the switch to DST.7 Psychiatric outcomes, including deaths due to suicide and overdose, are worse with the spring transition.8

Is the problem with DST merely limited to springtime, when we lose an hour of sleep? Not quite. During the “fall back” period, despite theoretically gaining an hour of sleep opportunity, people exhibit evidence of sleep disruption, psychiatric issues, traffic accidents, and inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations. These consequences likely stem from a discordance between circadian and social time, which leads to an earlier awakening based on circadian physiology as opposed to the clock time.

The acute impact of changing our sleep patterns during transitions in clock time may be appreciated more readily, but the damage is much more insidious. Chronic exposure to light in the late evening creates a state of enhanced arousal when the body should be winding down. The chronic incongruency between clock and solar time leads to dyssynchrony in our usual functions, such as food intake, social and physical activity, and basal temperature. Consequently, there is an impetus to fall asleep later. This leads to an accumulation of sleep debt and its associated negative consequences in the general, already chronically sleep-deprived population. This is especially impactful to adolescents and young adults who tend to have a delay in their sleep and wake patterns and, yet, are socially bound to early morning awakenings for school or work.

The scientific evidence behind the health risk and benefit profile of DST and ST is incontrovertible and in favor of ST. The hallmark of appropriate sleep habits involves consistency and appropriate duration. Changing timing forward or backward increases the likelihood of an alteration of the baseline established sleep and circadian consistency.

Unfortunately, despite multiple polls demonstrating the populace’s dislike of DST, repeat attempts to codify DST and negate ST persist. The latest initiative, the Sunshine Protection Act, which promised permanent DST, was passed by the US Senate but was thankfully foiled by Congress in 2022. The act of setting a time is not one that should be taken lightly or in isolation because there are significant, long-lasting health, safety, and socioeconomic consequences of this decision. Practically, this entails a concerted effort from all major economies since consistency is essential for trade and geopolitical relations. China, Japan, and India don’t practice DST. The European Parliament voted successfully to abolish DST in the European Union in 2019 with a plan to implement ST in 2021. Implementation has yet to be successful due to interruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the current economic and political climate in Europe. Political or theoretical political victories should not supersede the health and safety of an elected official’s constituents. As a medical community, we should continue to use our collective voice to encourage our representatives to vote in ways that positively affect our patients’ health outcomes.

References:

1. Rishi MA, et al. JCSM. 2024;20(1):121.

2. Gibson M, et al. Rev Econ Stat. 2018;100(5):783.

3. Jansky I, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1966.

4. Sipilia J, et al. Sleep Med. 2016;27-28:20.

5. Chudow JJ, et al. Sleep Med. 2020;69:155.

6. Fritz J, et al. Curr Biol. 2020;30(4):729.

7. Ferrazzi E, et al. J Biol Rhythms. 2018;33(5):555-564.

8. Berk M, et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2008;6(1):22.

The Gamer Who Became a GI Hospitalist and Dedicated Endoscopist

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

Reflecting on his career in gastroenterology, Andy Tau, MD, (@DrBloodandGuts on X) claims the discipline chose him, in many ways.

“I love gaming, which my mom said would never pay off. Then one day she nearly died from a peptic ulcer, and endoscopy saved her,” said Dr. Tau, a GI hospitalist who practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Texas. One of his specialties is endoscopic hemostasis.

Endoscopy functions similarly to a game because the interface between the operator and the patient is a controller and a video screen, he explained. “Movements in my hands translate directly onto the screen. Obviously, endoscopy is serious business, but the tactile feel was very familiar and satisfying to me.”

Advocating for the GI hospitalist and the versatile role they play in hospital medicine, is another passion of his. “The dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist,” Dr. Tau wrote in an opinion piece in GI & Hepatology News .

He expounded more on this topic and others in an interview, recalling what he learned from one mentor about maintaining a sense of humor at the bedside.

Q: You’ve said that GI hospitalists are the future of patient care. Can you explain why you feel this way?

Dr. Tau: From a quality perspective, even though it’s hard to put into one word, the care of acute GI pathology and endoscopy can be seen as a specialty in and of itself. These skills include hemostasis, enteral access, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), balloon-assisted enteroscopy, luminal stenting, advanced tissue closure, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The greater availability of a GI hospitalist, as opposed to an outpatient GI doctor rounding at the ends of days, likely shortens admissions and improves the logistics of scheduling inpatient cases.

From a financial perspective, the landscape of GI practice is changing because of GI physician shortages relative to increased demand for outpatient procedures. Namely, the outpatient gastroenterologists simply have too much on their plate and inefficiencies abound when they have to juggle inpatient and outpatient work. Thus, two tracks are forming, especially in large busy hospitals. This is the same evolution of the pure outpatient internist and inpatient internist 20 years ago.

Q: What attributes does a GI hospitalist bring to the table?

Dr. Tau: A GI hospitalist is one who can multitask through interruptions, manage end-of-life issues, craves therapeutic endoscopy (even if that’s hemostasis), and can keep more erratic hours based on the number of consults that come in. She/he tends to want immediate gratification and doesn’t mind the lack of continuity of care. Lastly, the GI hospitalist has to be brave and yet careful as the patients are sicker and thus complications may be higher and certainly less well tolerated.

Q: Are there enough of them going into practice right now?

Dr. Tau: Not really! The demand seems to outstrip supply based on what I see. There is a definite financial lure as the market rate for them rises (because more GIs are leaving the hospital for pure outpatient practice), but burnout can be an issue. Interestingly, fellows are typically highly trained and familiar with inpatient work, but once in practice, most choose the outpatient track. I think it’s a combination of work-life balance, inefficiency of inpatient endoscopy, and perhaps the strain of daily, erratic consultation.

Q: You received the 2021 Travis County Medical Society (TCMS) Young Physician of the Year. What achievements led to this honor?

Dr. Tau: I am not sure I am deserving of that award, but I think it was related to personal risk and some long hours as a GI hospitalist during the COVID pandemic. I may have the unfortunate distinction of performing more procedures on COVID patients than any other physician in the city. My hospital was the largest COVID-designated site in the city. There were countless PEG tubes in COVID survivors and a lot of bleeders for some reason. A critical care physician on the front lines and health director of the city of Austin received Physician of the Year, deservedly.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Dr. Tau: David Y. Graham, MD, MACG, got me into GI as a medical student and taught me to never tolerate any loose ends when it came to patient care as a resident. He trained me at every level — from medical school, residency, and through my fellowship. His advice is often delivered sly and dry, but his humor-laden truths continue to ring true throughout my life. One story: my whole family tested positive for Helicobacter pylori after my mother survived peptic ulcer hemorrhage. I was the only one who tested negative! I asked Dr Graham about it and he quipped, “You’re lucky! It’s because your mother didn’t love (and kiss) you as much!”

Even to this moment I laugh about that. I share that with my patients when they ask about how they contracted H. pylori.

Lightning Round

Favorite junk food?

McDonalds fries

Favorite movie genre?

Psychological thriller

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

What was your favorite Halloween costume?

Ninja turtle

Favorite sport:

Football (played in college)

Introvert or extrovert?

Extrovert unless sleep deprived.

Favorite holiday:

Thanksgiving

The book you read over and over:

Swiss Family Robinson

Favorite travel destination:

Hawaii

Optimist or pessimist?

A happy pessimist.

AGA Tech Summit Focuses on Accelerating Innovation

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

The AGA Tech Summit is building on the success of past summits and moving in a new direction. The reimagined summit will accelerate innovation by bringing together MedTech startups, innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

“It’s a new world out there. The Tech Summit now reflects the new direction AGA is taking in innovation,” said Lawrence R. Kosinski, MD, AGA at-large councilor for development and growth. “We want to help GI innovators successfully navigate the innovation lifecycle from start to finish and bring new technologies to market.”

The Tech Summit will take place April 11-12 in Chicago at MATTER, located at the Merchandise Mart. MATTER supports healthcare startups at all stages of growth and brings together industry executives, entrepreneurs, and investors to accelerate innovation, advance care and improve lives.

Highlights of the Tech Summit include:

- Keynote addresses from leaders in the field of GI innovation.

- Panel discussions with VC strategists.

- The Shark Tank Pitch Competition featuring emerging GI technologies.

- Multiple opportunities to network innovators, investors and leaders in the field.

- One-on-one consultations with VCs.

.

AGA Gives Guidance on Subepithelial Lesions

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.