User login

Intermittent fever and gradually progressive low back pain

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Transrectal ultrasonography–guided needle biopsy of the prostate confirms a diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

With the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in men in the United States. Most patients have localized stage at diagnosis; however, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer at diagnosis is steadily increasing. Five-year survival for distant-stage prostate cancer is approximately 32%.

High serum levels of PSA have been associated with bone metastases in men with prostate cancer, and the presence of metastatic disease increases with rising PSA levels. Over the past several decades, PSA levels > 100 ng/mL have been used as a marker for metastatic prostate cancer. However, not all men with metastatic prostate cancer will have elevated PSA levels, and bone imaging is necessary for correct staging and treatment stratification.

Bone metastases occur in approximately 70% of men with advanced prostate cancer, most often in the spine, and are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Bone metastases can cause severe pain, particularly in the evening; decreased mobility; pathologic fractures; spinal cord compression; bone marrow aplasia; and hypercalcemia.

The bone marrow represents a fertile soil into which prostate tumors can colonize and proliferate. Such colonization by prostate tumor cells is commonly associated with tumor-induced bone lesions, which typically arise from an imbalance between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-absorbing osteoclasts generated by prostate cancer cells. Whereas most solid tumors, such as breast cancer and melanoma, have a propensity for causing osteolytic lesions with excessive bone resorption, bone lesions resulting from prostate cancer are largely osteoblastic and are associated with uncontrolled low-quality bone formation. The resultant metastases have a unique bone formation that can be detected by plain radiography, bone scan, bone biopsy, and increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels.

CT; skeletal scintigraphy and PET; and single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI are recommended diagnostics for men at risk for prostate cancer metastasis. Radiotracer-based PET, which mainly uses altered metabolic activity or explicitly overexpressed receptors, is a promising diagnostic modality. However, the choice of a respective radiotracer must be carefully considered because a single radiotracer is typically insufficient to visualize all clinical stages of prostate cancer. In addition, its use is reliant on the extent of malignant tissue, tumor heterogeneity, and previous treatments.

Systemic androgen-deprivation therapy, with or without docetaxel-based chemotherapy, is the standard of care for metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is largely directed at preventing skeletal-related events and providing pain management.

Radium-223 is the only available therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer that specifically targets bone metastases, delays development of skeletal-related events, and improves survival. Based on the results of the ALSYMPCA study, radium-223 in combination with systemic therapies is now considered an effective, efficient, and well-tolerated therapy for castrate-resistant prostate cancer with bone lesions.

The effects of local radiation therapy for men with metastatic prostate cancer and the optimal combination of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting are still under investigation.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 71-year-old homeless man presents to the emergency department (ED) with intermittent fever, gradually progressive low back pain restricting physical activities and movement, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and poor appetite. The patient has been seen in the same ED sporadically over the years for various problems, and his medical history is notable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tobacco use, alcoholism, and foot infections. Physical examination findings include tenderness to percussion over the thoracic and lumbar spine and a mildly enlarged prostate that appears to be smooth, normal in texture, and lacking nodules on digital rectal exam. Complete blood cell count and chemistry panel are normal. Both alkaline phosphatase and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are elevated, at 240 U/L and 115 ng/mL, respectively. Urinalysis shows hematuria. CT shows osteolytic lesions in the patient's lumbar spine and femur.

DEMO: Dyspnea and intercostal retractions

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

A 17-year-old boy came to the hospital with shortness of breath and loud wheezing. His mother explained that earlier that day, he visited a friend’s house where they played video games together in the basement. When he returned home, he noticed that he was becoming breathless while talking. His chest radiograph findings were normal, but intercostal retractions were observed. His heart rate is 120 beats/minute.

DEMO: Persistent cough and dyspnea

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

A 6-year-old girl came to the hospital with a persistent cough, episodes of dyspnea, and a slight fever. Her mother reported that she had been diagnosed with asthma when she was 4 years old. Despite strict adherence to anti-inflammatory medication, she experiences frequent symptoms, especially at night, and she had been hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation 8 months ago. Posterior-anterior chest radiograph revealed blurring of the right border of the heart.

What's your diagnosis?

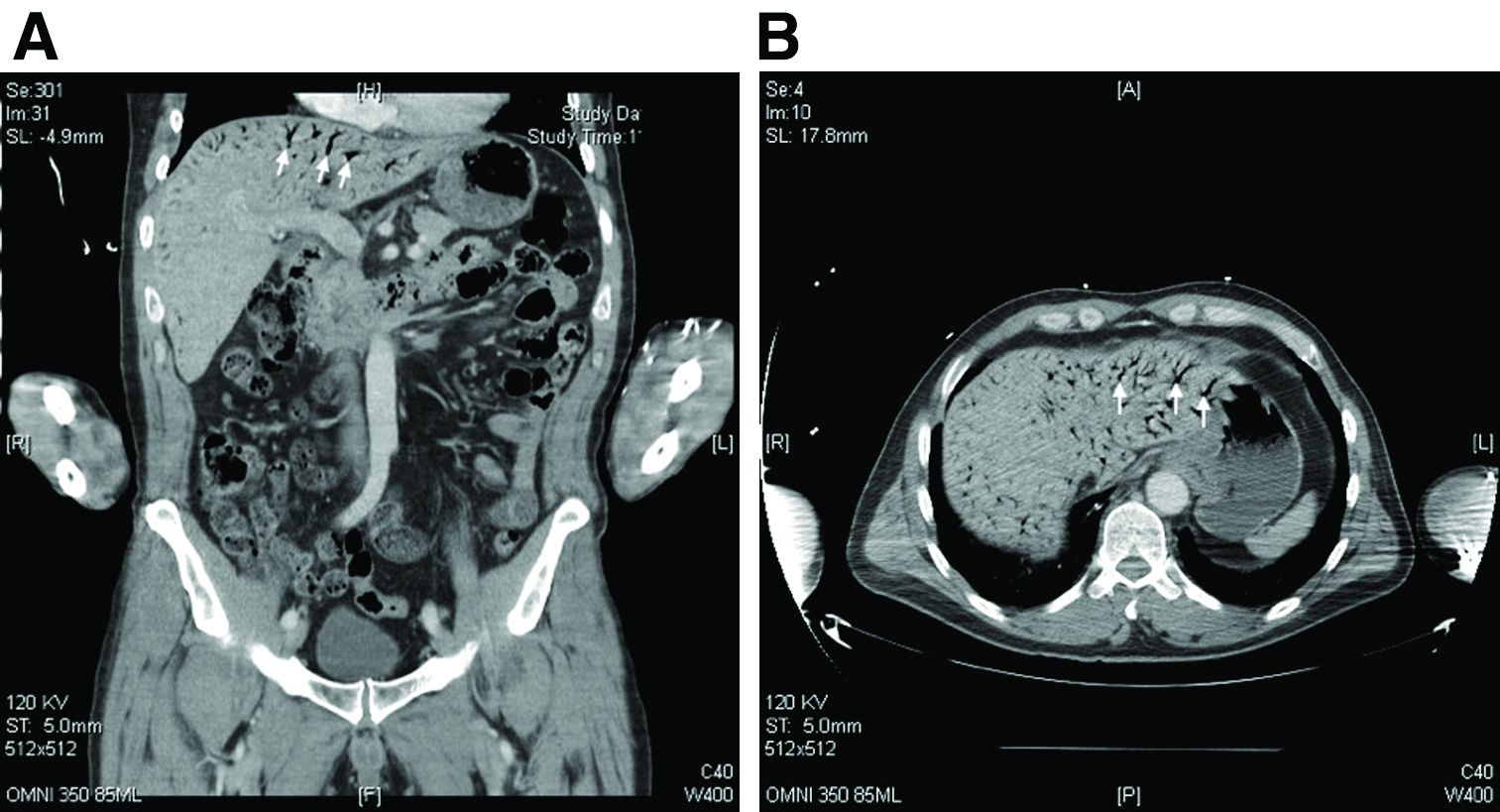

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

How should this condition be managed?

Sudden eruption of pruritus and pain

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD and eczema herpeticum. A Tzanck smear is done and is positive for multinucleate giant cells with nuclear molding and ballooning degeneration of the keratinocytes.

Eczema herpeticum, or Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of AD. It is an extensive cutaneous vesicular eruption that arises from pre-existing skin disease — in most cases, AD — and is caused by disseminated cutaneous viral infection, usually with the herpes simplex virus (HSV). The virus can infect the epidermis because of the skin barrier defects that are inherently associated with AD. Patients with AD and filaggrin gene null mutations may have an increased risk for eczema herpeticum.

Eczema herpeticum is associated with significant morbidity and is considered a medical emergency. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential to prevent or minimize complications. Complications of eczema herpeticum can include keratoconjunctivitis, which may lead to vision loss, as well as multiorgan involvement with meningoencephalitis and/or septic shock.

Eczema herpeticum occurs on areas of preexisting AD (or other skin disease) and presents as small, dome-shaped, grouped papule-vesicles on an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out ulcers are formed. It is seen most often on the face, neck, and upper trunk. Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathies may also be present.

Among patients with severe or poorly controlled AD, even the classic presentation of eczema herpeticum can be challenging to recognize. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this complication in any patient with AD who presents with an acute pruritic and painful rash, including pediatric patients, who have the highest risk for the development of eczema herpeticum.

Viral PCR on vesicle fluid can confirm the diagnosis of eczema herpeticum and determine the type of HSV with high sensitivity and specificity. If unavailable, a Tzanck smear of an opened vesicle or erosion can confirm an HSV infection and provide rapid diagnosis, but its sensitivity and specificity can vary. Direct fluorescence antigen testing is a fast and inexpensive method for detecting an HSV antigen and distinguishing between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections. Bacterial cultures should be performed when there is a concern for impetiginization. A skin biopsy may be indicated in cases involving atypical presentation.

Immediate treatment with oral acyclovir should be initiated for any patient with eczema herpeticum; patients with severe disease or who are immunocompromised may require hospitalization for administration of systemic antivirals. Because secondary bacterial infections are common, prophylactic antibiotics (eg, cephalexin, clindamycin, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) may also be indicated. Finally, consultation with an ophthalmologist is indicated when herpes keratitis is suspected.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD and eczema herpeticum. A Tzanck smear is done and is positive for multinucleate giant cells with nuclear molding and ballooning degeneration of the keratinocytes.

Eczema herpeticum, or Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of AD. It is an extensive cutaneous vesicular eruption that arises from pre-existing skin disease — in most cases, AD — and is caused by disseminated cutaneous viral infection, usually with the herpes simplex virus (HSV). The virus can infect the epidermis because of the skin barrier defects that are inherently associated with AD. Patients with AD and filaggrin gene null mutations may have an increased risk for eczema herpeticum.

Eczema herpeticum is associated with significant morbidity and is considered a medical emergency. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential to prevent or minimize complications. Complications of eczema herpeticum can include keratoconjunctivitis, which may lead to vision loss, as well as multiorgan involvement with meningoencephalitis and/or septic shock.

Eczema herpeticum occurs on areas of preexisting AD (or other skin disease) and presents as small, dome-shaped, grouped papule-vesicles on an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out ulcers are formed. It is seen most often on the face, neck, and upper trunk. Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathies may also be present.

Among patients with severe or poorly controlled AD, even the classic presentation of eczema herpeticum can be challenging to recognize. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this complication in any patient with AD who presents with an acute pruritic and painful rash, including pediatric patients, who have the highest risk for the development of eczema herpeticum.

Viral PCR on vesicle fluid can confirm the diagnosis of eczema herpeticum and determine the type of HSV with high sensitivity and specificity. If unavailable, a Tzanck smear of an opened vesicle or erosion can confirm an HSV infection and provide rapid diagnosis, but its sensitivity and specificity can vary. Direct fluorescence antigen testing is a fast and inexpensive method for detecting an HSV antigen and distinguishing between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections. Bacterial cultures should be performed when there is a concern for impetiginization. A skin biopsy may be indicated in cases involving atypical presentation.

Immediate treatment with oral acyclovir should be initiated for any patient with eczema herpeticum; patients with severe disease or who are immunocompromised may require hospitalization for administration of systemic antivirals. Because secondary bacterial infections are common, prophylactic antibiotics (eg, cephalexin, clindamycin, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) may also be indicated. Finally, consultation with an ophthalmologist is indicated when herpes keratitis is suspected.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is empirically diagnosed with AD and eczema herpeticum. A Tzanck smear is done and is positive for multinucleate giant cells with nuclear molding and ballooning degeneration of the keratinocytes.

Eczema herpeticum, or Kaposi varicelliform eruption, is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of AD. It is an extensive cutaneous vesicular eruption that arises from pre-existing skin disease — in most cases, AD — and is caused by disseminated cutaneous viral infection, usually with the herpes simplex virus (HSV). The virus can infect the epidermis because of the skin barrier defects that are inherently associated with AD. Patients with AD and filaggrin gene null mutations may have an increased risk for eczema herpeticum.

Eczema herpeticum is associated with significant morbidity and is considered a medical emergency. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential to prevent or minimize complications. Complications of eczema herpeticum can include keratoconjunctivitis, which may lead to vision loss, as well as multiorgan involvement with meningoencephalitis and/or septic shock.

Eczema herpeticum occurs on areas of preexisting AD (or other skin disease) and presents as small, dome-shaped, grouped papule-vesicles on an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out ulcers are formed. It is seen most often on the face, neck, and upper trunk. Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathies may also be present.

Among patients with severe or poorly controlled AD, even the classic presentation of eczema herpeticum can be challenging to recognize. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this complication in any patient with AD who presents with an acute pruritic and painful rash, including pediatric patients, who have the highest risk for the development of eczema herpeticum.

Viral PCR on vesicle fluid can confirm the diagnosis of eczema herpeticum and determine the type of HSV with high sensitivity and specificity. If unavailable, a Tzanck smear of an opened vesicle or erosion can confirm an HSV infection and provide rapid diagnosis, but its sensitivity and specificity can vary. Direct fluorescence antigen testing is a fast and inexpensive method for detecting an HSV antigen and distinguishing between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections. Bacterial cultures should be performed when there is a concern for impetiginization. A skin biopsy may be indicated in cases involving atypical presentation.

Immediate treatment with oral acyclovir should be initiated for any patient with eczema herpeticum; patients with severe disease or who are immunocompromised may require hospitalization for administration of systemic antivirals. Because secondary bacterial infections are common, prophylactic antibiotics (eg, cephalexin, clindamycin, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) may also be indicated. Finally, consultation with an ophthalmologist is indicated when herpes keratitis is suspected.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 24-year-old woman with a history of moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) and mild intermittent asthma presents with a sudden eruption of widespread pruritus and pain affecting her torso. Physical examination reveals small, dome-shaped, grouped papule-vesicles and some punched-out erosions on an erythematous base. The patient was last treated with topical triamcinolone for AD 6 weeks before. Current medications include an inhaled short-acting, beta-2 agonist used as needed for asthma symptoms and levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol tablets for oral contraception.

Widespread pruritic lesions on torso

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) on the basis of clinical findings and historical features, morphology and distribution of skin lesions, and associated clinical signs.

AD continues to be a clinical diagnosis. Pruritus and eczema (acute, subacute, or chronic) are essential features for the diagnosis of AD. The eczema should follow characteristic morphology and age-specific patterns (eg, facial/neck/extensor involvement in children, flexural involvement in any age group, sparing of the groin and axillary regions). A personal or family history of atopy is an important historical feature that supports the diagnosis of AD, as are xerosis and early age of onset.

The majority of patients with AD (60%) develop symptoms during the first year of life and 90% experience an eruption by 5 years of age, but disease onset can occur at any age. Some studies have found an association between late-onset AD and persistence of disease into adulthood.

At present, there are no reliable biomarkers that can differentiate AD from other entities. An elevated total and/or allergen-specific serum IgE level is the most commonly associated laboratory feature, but it is not seen in about 20% of individuals with AD. Additionally, elevated allergen-specific IgE levels are found in 55% of the general population in the United States, making it nonspecific for AD. Moreover, while total IgE level usually varies in accordance with disease severity, it is not a reliable marker of disease severity, and it is possible for individuals with severe disease to have normal levels. Nonatopic conditions (eg, parasitic infection, some cancers, and autoimmune disease) may also lead to elevations in IgE levels.

Consistent prognostic markers are also lacking, although elevated total serum IgE levels and filaggrin gene null mutations do tend to be predictive of a more severe and prolonged disease course.

Topical agents including nonpharmacologic moisturizers and topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for AD; immunomodulatory agents and targeted biologic therapies are also available. For patients with more severe or recalcitrant disease, systemic therapy or phototherapy may be used, often in conjunction with topical therapies.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) on the basis of clinical findings and historical features, morphology and distribution of skin lesions, and associated clinical signs.

AD continues to be a clinical diagnosis. Pruritus and eczema (acute, subacute, or chronic) are essential features for the diagnosis of AD. The eczema should follow characteristic morphology and age-specific patterns (eg, facial/neck/extensor involvement in children, flexural involvement in any age group, sparing of the groin and axillary regions). A personal or family history of atopy is an important historical feature that supports the diagnosis of AD, as are xerosis and early age of onset.

The majority of patients with AD (60%) develop symptoms during the first year of life and 90% experience an eruption by 5 years of age, but disease onset can occur at any age. Some studies have found an association between late-onset AD and persistence of disease into adulthood.

At present, there are no reliable biomarkers that can differentiate AD from other entities. An elevated total and/or allergen-specific serum IgE level is the most commonly associated laboratory feature, but it is not seen in about 20% of individuals with AD. Additionally, elevated allergen-specific IgE levels are found in 55% of the general population in the United States, making it nonspecific for AD. Moreover, while total IgE level usually varies in accordance with disease severity, it is not a reliable marker of disease severity, and it is possible for individuals with severe disease to have normal levels. Nonatopic conditions (eg, parasitic infection, some cancers, and autoimmune disease) may also lead to elevations in IgE levels.

Consistent prognostic markers are also lacking, although elevated total serum IgE levels and filaggrin gene null mutations do tend to be predictive of a more severe and prolonged disease course.

Topical agents including nonpharmacologic moisturizers and topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for AD; immunomodulatory agents and targeted biologic therapies are also available. For patients with more severe or recalcitrant disease, systemic therapy or phototherapy may be used, often in conjunction with topical therapies.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) on the basis of clinical findings and historical features, morphology and distribution of skin lesions, and associated clinical signs.

AD continues to be a clinical diagnosis. Pruritus and eczema (acute, subacute, or chronic) are essential features for the diagnosis of AD. The eczema should follow characteristic morphology and age-specific patterns (eg, facial/neck/extensor involvement in children, flexural involvement in any age group, sparing of the groin and axillary regions). A personal or family history of atopy is an important historical feature that supports the diagnosis of AD, as are xerosis and early age of onset.

The majority of patients with AD (60%) develop symptoms during the first year of life and 90% experience an eruption by 5 years of age, but disease onset can occur at any age. Some studies have found an association between late-onset AD and persistence of disease into adulthood.

At present, there are no reliable biomarkers that can differentiate AD from other entities. An elevated total and/or allergen-specific serum IgE level is the most commonly associated laboratory feature, but it is not seen in about 20% of individuals with AD. Additionally, elevated allergen-specific IgE levels are found in 55% of the general population in the United States, making it nonspecific for AD. Moreover, while total IgE level usually varies in accordance with disease severity, it is not a reliable marker of disease severity, and it is possible for individuals with severe disease to have normal levels. Nonatopic conditions (eg, parasitic infection, some cancers, and autoimmune disease) may also lead to elevations in IgE levels.

Consistent prognostic markers are also lacking, although elevated total serum IgE levels and filaggrin gene null mutations do tend to be predictive of a more severe and prolonged disease course.

Topical agents including nonpharmacologic moisturizers and topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for AD; immunomodulatory agents and targeted biologic therapies are also available. For patients with more severe or recalcitrant disease, systemic therapy or phototherapy may be used, often in conjunction with topical therapies.

Richard Vinson, MD, President, Mountain View Dermatology, El Paso, Texas.

Richard Vinson, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 15-year-old boy presents with widespread pruritic lesions on his torso. His mother explains that he had been seen by his pediatrician 2 weeks before and was diagnosed with scabies. The patient was treated with a topical scabicidal agent (permethrin 5% lotion) on diagnosis, with a repeat application 7 days later. Despite treatment, no improvement in the patient's symptoms have been noted. Physical examination reveals poorly defined, erythematous, scaly, and crusted patches and plaques. No other family members are experiencing symptoms. There is a positive family history for atopy.

Persistent cough and dyspnea

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Based on the patient’s history of asthma, physical examination, and radiograph findings, a diagnosis of right middle lung collapse was determined. Right middle lobe syndrome (RMLS) refers to chronic or recurrent atelectasis in the right middle lobe and can stem from numerous etiologies. It is characterized by wedge-shaped density that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the hilum of the lung. Atelectasis typically occurs in the right middle lobe, but the lingula may be involved as well.

Asthma may predispose patients to atelectasis, resulting from bronchial inflammation that produces cellular debris, mucus plugs, and edema.Children are also more prone to developing atelectasis than adults because of smaller and more collapsible airways, among other features.

Lateral chest radiography is the most effective imaging technique in patients presenting with RMLS, revealing the condition's hallmark findings: a loss of volume in the right middle lobe and a blurred right heart border.

For appropriate treatment, a precise diagnosis of the pathology underlying the RMLS must be determined. This case represents a complication of uncontrolled asthma. The cornerstone of therapy is chest physical therapy and postural drainage, and the addition of mucolytics and dornase alfa may further clear airways. Children with asthma should be treated with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy such as inhaled steroids, and the clinician may consider the addition of systemic steroids.

Cases of RMLS involving neoplastic origin or bronchiectasis should be given special consideration. Diagnosis can be confirmed with high-resolution chest CT scanning, which is safer for younger patients or those with asthma than traditional bronchography.

If a patient’s symptoms are not responsive to therapy or if the patient has predisposition to airway colonization, the clinician should perform a bronchoalveolar lavage culture to determine an appropriate antibiotic. In children with asthma, there is an association between right middle lobe collapse and infection.

Long-term follow-up has demonstrated that with treatment, RMLS typically resolves within 90 days.Soyer and colleagues also determined that baseline treatment of asthma with anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate the resolution of atelectasis. However, recurrent infections may cause parenchymal damage and bronchiectasis.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 6-year-old girl came to the hospital with a persistent cough, episodes of dyspnea, and a slight fever. Her mother reported that she had been diagnosed with asthma when she was 4 years old. Despite strict adherence to anti-inflammatory medication, she experiences frequent symptoms, especially at night, and she had been hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation 8 months ago. Posterior-anterior chest radiograph revealed blurring of the right border of the heart.

Dyspnea and intercostal retractions

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably having a delayed allergenic response to an indoor mold allergen. Early reactions can occur immediately following allergen inhalation but can also manifest 4-10 hours after exposure to wet and damp areas, such as bathrooms and basements.

Allergic asthma represents the most common asthma phenotype. The average age of onset is younger than that of nonallergic asthma, with allergens triggering exacerbations in 60%-90% of children compared with 50% of adults.Triggers can include mold spores, seasonal pollen, dust mites, and animal allergens. There is also an increased incidence of co-occurring allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis in patients with allergic asthma.

During an acute asthma exacerbation, lung examination findings may include wheezing, rhonchi, hyperinflation, or a prolonged expiratory phase. In children, supraclavicular and intercostal retractions and nasal flaring, as well as abdominal breathing, are particularly telling. Total serum immunoglobulin E levels are usually higher in allergic vs nonallergic asthma (> 100 IU), although this marker is not specific to asthma.

The allergic asthma phenotype usually responds to inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Although evidence suggests that allergic vs nonallergic asthma is less severe in many cases, compelling data point to a causal relationship between mold allergy and asthma severity in a subgroup of younger asthma patients; specifically, mold sensitization may be associated with asthma attacks requiring hospital admission in this population.

Although spirometry assessments should be obtained as the primary test to establish the asthma diagnosis, to test for allergic sensitivity to specific allergens in the environment, allergy skin tests and blood radioallergosorbent tests may be used. Up to 85% of patients with asthma demonstrate positive skin test results, and in children, this sensitization is reflective of disease activity. Such testing for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E is critical in prescribing allergen avoidance techniques and allergen immunotherapy regimens, although the method shows a relatively high false positive rate and should not be performed during an exacerbation.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 17-year-old boy came to the hospital with shortness of breath and loud wheezing. His mother explained that earlier that day, he visited a friend’s house where they played video games together in the basement. When he returned home, he noticed that he was becoming breathless while talking. His chest radiograph findings were normal, but intercostal retractions were observed. His heart rate is 120 beats/minute.

Question 1

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Correct answer: D. Antienterocyte antibodies

Rationale

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is characterized by a severe malabsorption and secretory diarrhea, and is differentiated from celiac disease on small-bowel biopsy by the decreased numbers or absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, apoptotic bodies present in the intestinal crypts, and absent goblet and Paneth cells. Patients with AIE may also carry other autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A group at the Mayo Clinic has published a set of diagnostic criteria based on their case series of adult AIE that requires ruling out other causes of chronic diarrhea in adults, specific histology supportive of AIE, and presence of malabsorption and ruling out other causes of villous atrophy. The presence of antienterocyte or antigoblet cell antibodies are supportive of a diagnosis of AIE, but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

References

Akram S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1282-90.

Montalto M et al. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(9):1029-36.

Q1. A 55-year-old woman presents with a one-year history of large volume foul-smelling stools that float in water associated with 40-pound weight loss. Laboratory evaluation reveals low vitamin A and D levels. An upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies reveals complete villous blunting with decreased goblet and Paneth cells, absence of surface intraepithelial lymphocytes, and increased crypt apoptosis. She denies nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, celiac serologies were not elevated, and a glucose hydrogen breath test was negative. She also has coexisting rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Have you used ambulatory cervical ripening in your practice?

[polldaddy:10771173]

[polldaddy:10771173]

[polldaddy:10771173]