User login

Hospital Buprenorphine Program for Opioid Use Disorder Is Associated With Increased Inpatient and Outpatient Addiction Treatment

Hospitalizations related to opioid use disorder (OUD) have increased and now account for up to 6% of hospital admissions in certain areas of the United States.1 Patients with OUD who are started on buprenorphine during hospitalization are more likely to enter outpatient treatment, stay in treatment longer, and have more drug-free days compared with patients who only receive a referral for outpatient treatment.2,3 Therefore, a crucial comprehensive strategy for OUD care should include hospital-based programs that support initiation of treatment in the inpatient setting and strong bridges to outpatient care. One of the common barriers to initiating treatment in the inpatient setting, however, is a lack of access to addiction medicine specialists.4-6

In 2017, we created a hospitalist-led interprofessional team called the B-Team (Buprenorphine Team) to help primary care teams identify patients with OUD, initiate and maintain buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization, provide warm handoffs to outpatient treatment programs, and reduce institutional stigma related to people with substance use disorders.

METHODS

Program Description

The B-Team is led by a hospital medicine physician assistant and includes physicians from internal medicine, consult-liaison psychiatry, and palliative care; advanced practice and bedside nurses; a social worker; a pharmacist; a chaplain; a peer-recovery specialist; and medical trainees. The B-Team is notified of potential candidates for buprenorphine through a secure texting platform, one that is accessible to any healthcare provider at the hospital. Patients who are referred to the B-Team either self-identify or are identified by their primary team as having an underlying OUD. One of the B-Team providers assesses the patient to determine if they are eligible to receive inpatient therapy. Patients are considered eligible for the program if they meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) criteria for OUD, have a desire to cease opioid use, and receive medical clearance to take buprenorphine.

For eligible patients, the B-Team provider orders a nurse-driven protocol to initiate buprenorphine for OUD. The chaplain offers psychospiritual counseling, and the social worker provides counseling and coordination of care. The B-Team partners with a nonhospital-affiliated, publicly-funded, office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) program that combines primary care with behavioral health programming. A follow-up outpatient appointment is secured prior to hospital discharge, and a member of the B-Team who has Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) X-waiver certification prescribes buprenorphine as a bridge until the follow-up appointment. The medication is dispensed from the hospital’s retail pharmacy, and the patient leaves the hospital with the medication in-hand.

Patients who are not eligible for buprenorphine therapy are offered a harm-reduction intervention or referral to the psychiatry consult liaison service to assess for alternative diagnoses or treatment. These patients are also offered psychospiritual counseling and a prescription for naloxone.

Prior to the creation of the B-Team at our hospital, there was no structure in place to facilitate initiation of buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization and no linkage to outpatient treatment after discharge; furthermore, none of the hospitalists or other providers (including consulting psychiatrists) had an X-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD.

Program Evaluation

Study data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture software. Inpatient and outpatient data were entered by a B-Team provider or a researcher via chart review. Patients were considered to be engaged in care if they attended at least one outpatient appointment for buprenorphine therapy during each of the following time periods: (1) 0 to 27 days (initial follow-up), 28-89 days (1- to 3-month follow-up), 90-179 days (3- to 6-month follow-up), and 180 days or more (>6-month follow-up). Only visits specifically for buprenorphine maintenance therapy were counted. If multiple encounters occurred within one time frame, the encounter closest to 0, 30, 90, or 180 days from discharge was used. If a patient did not attend any encounters during a specified time frame, they were considered to no longer be engaged in care and were no longer tracked for purposes of the evaluation. Data for the percentage of patients engaged in outpatient care are presented as the number of patients who attended at least one appointment during each of the follow-up periods (1 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, or after 6 months, as noted above) divided by the number of patients who had been discharged with coordinated follow-up.

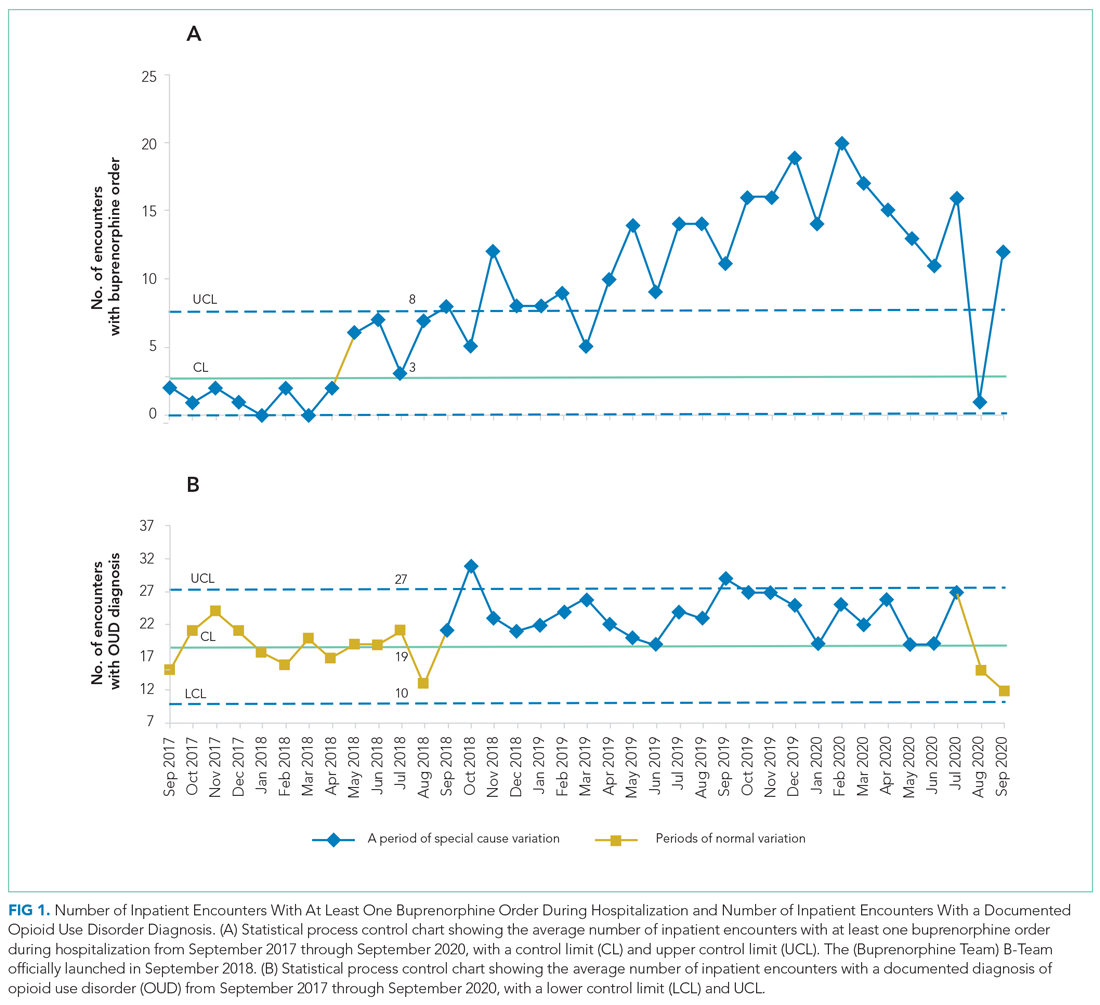

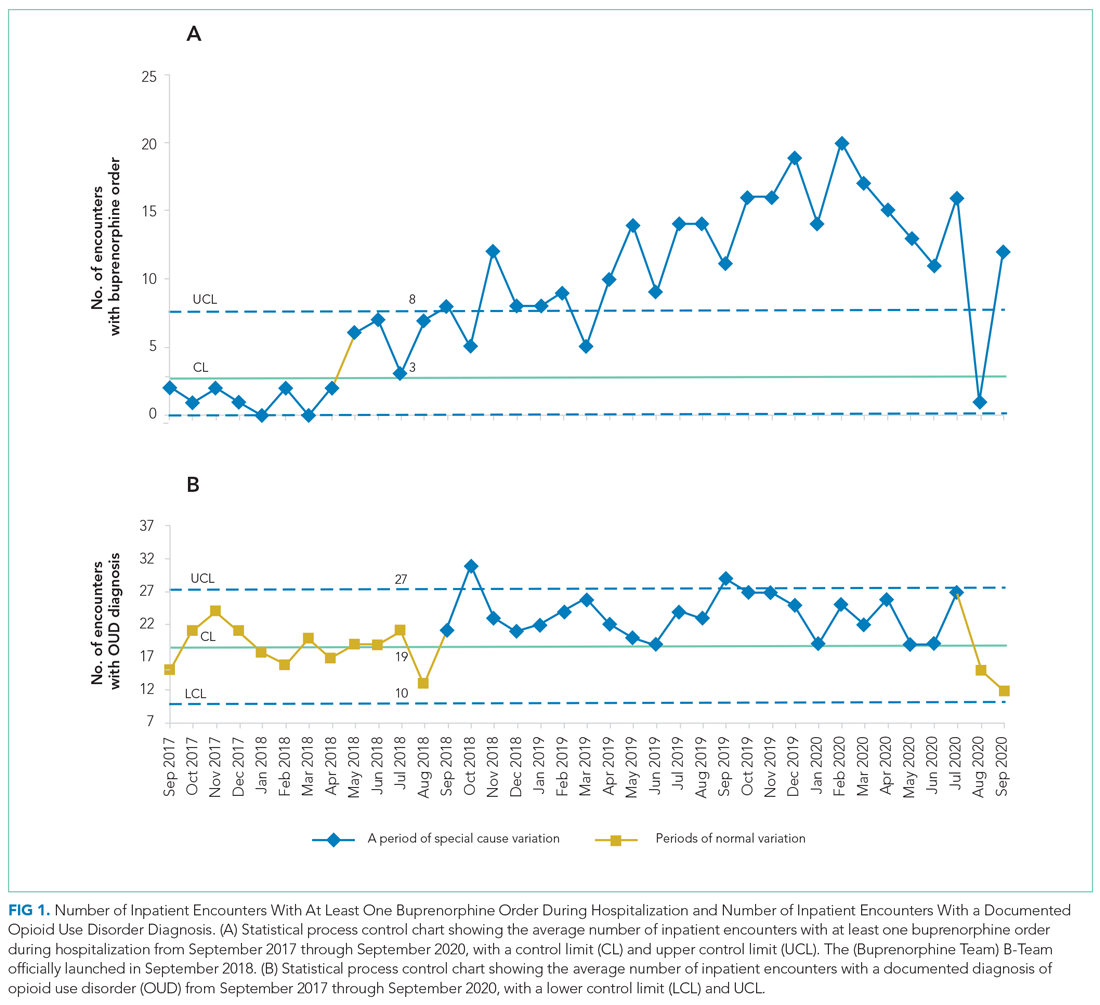

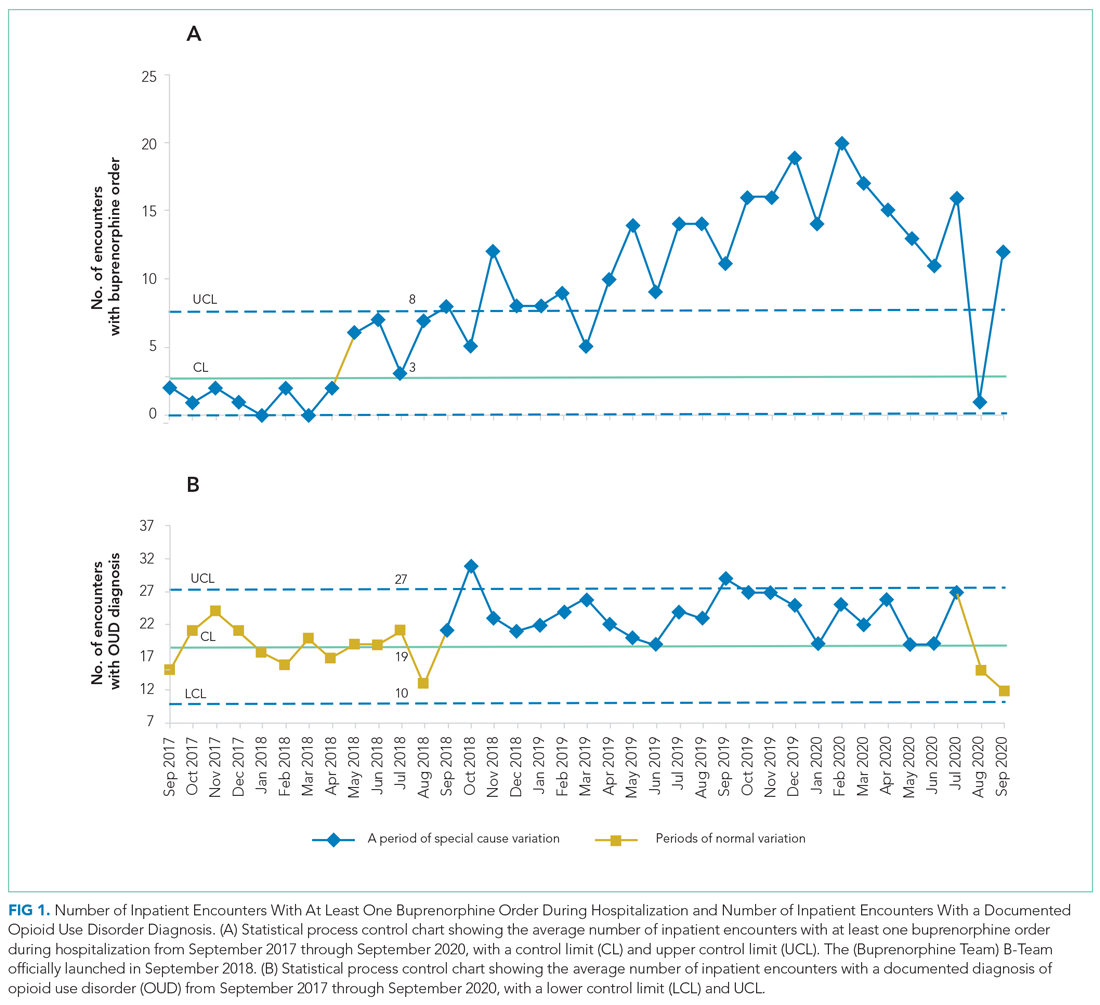

The number of patients admitted per month for whom there was an order to initiate inpatient buprenorphine therapy was analyzed using a statistical process control chart,

This program and study were considered quality improvement by The University of Texas Institutional Review Board and did not meet criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

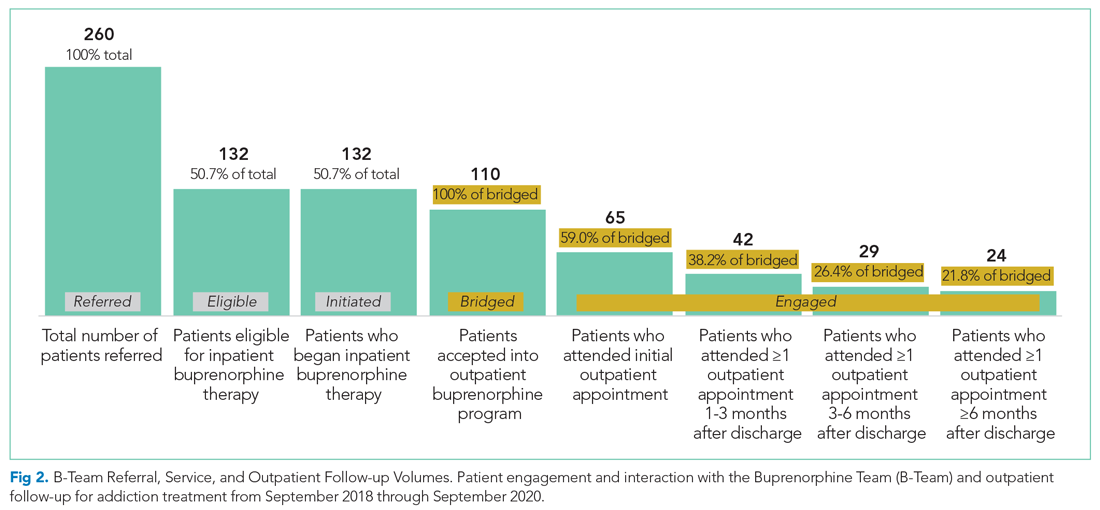

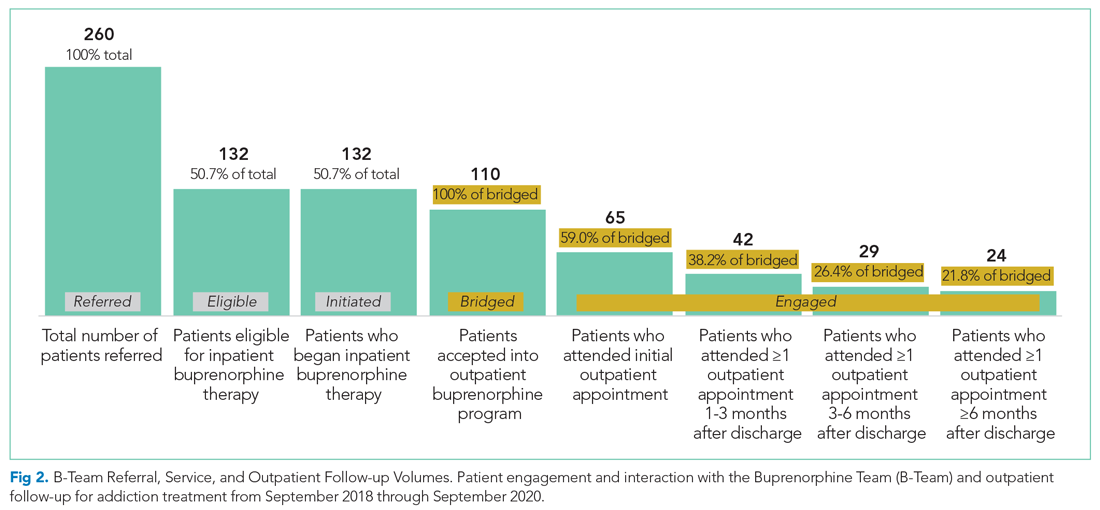

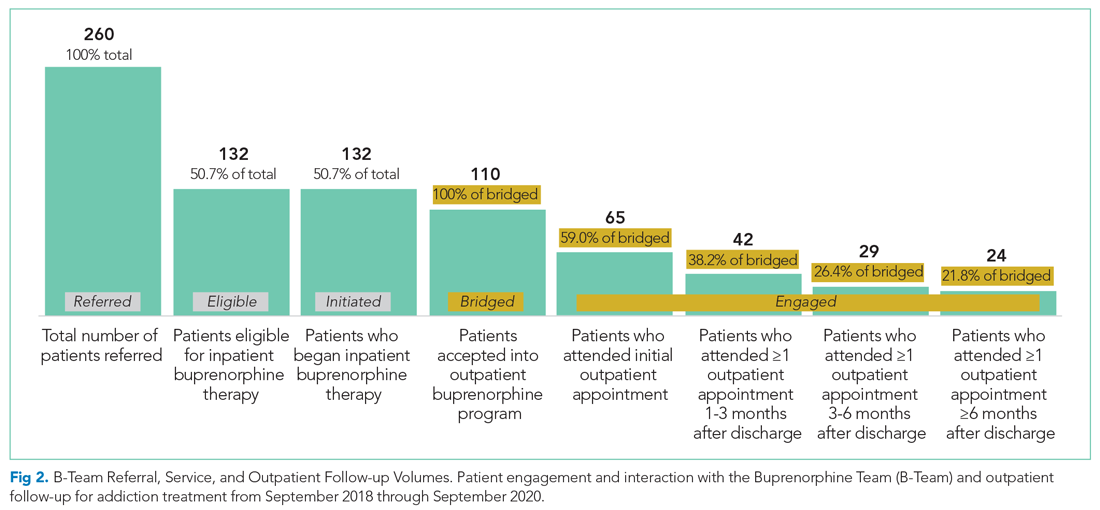

During the first 2 years of the program (September 2018-September 2020), the B-Team received 260 patient referrals. Most of the patients were White (72%), male (62%), and between ages 25 and 44 years (53%) (Appendix Table). The team initiated buprenorphine therapy in 132 hospitalized patients. In the year prior to the creation of the B-Team program, the average number of hospitalized patients receiving buprenorphine for OUD per month was three; after the launch of the B-Team program, this number increased

The B-Team saw a total of 132 eligible patients; members of the team provided counseling, support, and resources regarding buprenorphine therapy. In addition, the B-Team’s chaplain provided emotional support and spiritual connection (if desired) to 40 of these patients (30%). In the study, no cases of precipitated withdrawal were identified. Of the 132 patients seen, 110 (83%) were accepted to an outpatient OUD program upon discharge from the hospital; 98 (89%) of these patients were accepted at our partner OBOT clinic. The remaining patients were not interested in continuing OUD treatment (13%) or were denied acceptance to an outpatient program based on administrative and/or financial eligibility guidelines (4%). Patients who would not be attending an outpatient program were discontinued on buprenorphine therapy prior to discharge, counseled about naloxone, and provided printed resources.

Outpatient appointment attendance was used to measure ongoing treatment engagement of the 110 patients who were discharged with coordinated follow-up care. A total of 65 patients (59%) attended their first outpatient appointment; the average time between discharge and the first outpatient appointment was 5.9 days. Forty-two patients (38%) attended at least one appointment between 1 and 3 months; 29 (26%) between 3 and 6 months; and 24 (22%) after 6 months (Figure 2).

Of the 128 patients who were not administered buprenorphine therapy, 64 (50%) were not interested in starting treatment and/or were not ready to engage in treatment; 36 (28%) did not meet criteria for OUD treatment; 28 (22%) were already receiving treatment or preferred another type of OUD treatment; and 13 (10%) had severe comorbid addiction and/or illness requiring treatment that contraindicates the use of buprenorphine.

DISCUSSION

A volunteer hospitalist-led interprofessional team providing evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD was associated with a substantial increase in patients receiving buprenorphine therapy—both during hospitalization and after discharge. In the program, 59% of patients attended initial follow-up appointments, and 22% of patients were still engaged at 6 months. These outpatient follow-up rates appear to be similar to, or higher than, other programs described in the literature. For example, a buprenorphine OUD-treatment initiative led by the psychiatry consult service at a Boston academic medical center resulted in less than half of patients receiving buprenorphine treatment within 2 months of discharge.7 In another study wherein an addiction medicine consult service administered buprenorphine to patients with OUD during hospitalization, 39%, 27%, and 18% of patients were retained in outpatient treatment at 30, 90, and 180 days, respectively.8

The B-Team model is likely generalizable to other hospital medicine groups that may not otherwise have access to inpatient care for substance use disorder. The B-Team is not an addiction medicine consultation service; rather, it is a hospitalist-led quality improvement initiative seeking to improve the standard of care for hospitalized patients with OUD.

A significant barrier is ensuring ongoing support for patients with OUD after discharge. In the B-Team program, a parallel OBOT program was created by a local nonaffiliated federally qualified health center. Although 89% of patients received treatment at this OBOT clinic, the inpatient team also has relationships with other local treatment centers, including programs that provide methadone. Another important barrier to high-quality outpatient care for OUD is the requirement of an X-waiver. To help overcome this barrier, our inpatient program partnered with a regional medical society to offer periodic X-waiver training to outpatient providers. In less than a year, more than 100 regional prescribers participated in this program.

Our study has several limitations. There was likely some degree of selection bias among the hospitalized patients who received initial buprenorphine treatment. To our knowledge, there is no specific validated screening tool for OUD in the inpatient acute care setting; moreover, we have been unable to implement standardized screening for OUD into the electronic health record. As such, we rely on the totality of the clinical circumstances approach to identify patients with OUD.

Furthermore, we had neither a comparison group nor a prospective plan to follow patients who did not remain engaged in care after discharge. In addition, our analysis of OUD admissions included F11 ICD-10 codes, which are limited by clinical documentation.9,10 Our program focuses exclusively on buprenorphine initiation due to insufficient immediate outpatient capacity for methadone initiated during hospitalization and lack of coverage for extended-release naltrexone. Limitations to outpatient data-sharing prevented the reporting of outpatient appointments external to the identified partner program; since these appointments were included in the analysis as “lost to follow-up,” actual engagement rates may be higher than those reported.

Moving forward, the B-Team is continuing to serve as a role model for appropriate, patient-centered, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD. Attending physicians and residents with an X-waiver are now encouraged to initiate buprenorphine treatment on their own. In June 2020, we added peer-recovery support services to the program, which has improved care for patients and increased adoption of hospital-initiated substance use disorder interventions.11 Lessons learned from inpatient implementation are being applied to our hospital’s emergency department and to an inpatient obstetrics unit at a partner hospital; they are also being employed to further empower hospitalists to diagnose and treat other substance use disorders, such as alcohol use disorder.

1. Owens PL, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML. Hospital Burden of Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays: Metropolitan and Rural Hospitals, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #258. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2020. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559382/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK559382.pdf

2. Liebschutz J, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556

3. Moreno JL, Wakeman SE, Duprey MS, Roberts RJ, Jacobson JS, Devlin JW. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019;13(4):306-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000499

4. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736

5. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice — integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1606157

6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024

7. Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: a case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12161

8. Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007

9. Jicha C, Saxon D, Lofwall MR, Fanucchi LC. Substance use disorder assessment, diagnosis, and management for patients hospitalized with severe infections due to injection drug use. J Addict Med. 2019;13(1):69-74. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000454

10. Heslin KC, Owens PL, Karaca Z, Barrett ML, Moore BJ, Elixhauser A. Trends in opioid-related inpatient stays shifted after the US transitioned to ICD-10-CM diagnosis coding in 2015. Med Care. 2017;55(11):918-923. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000805

11. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

Hospitalizations related to opioid use disorder (OUD) have increased and now account for up to 6% of hospital admissions in certain areas of the United States.1 Patients with OUD who are started on buprenorphine during hospitalization are more likely to enter outpatient treatment, stay in treatment longer, and have more drug-free days compared with patients who only receive a referral for outpatient treatment.2,3 Therefore, a crucial comprehensive strategy for OUD care should include hospital-based programs that support initiation of treatment in the inpatient setting and strong bridges to outpatient care. One of the common barriers to initiating treatment in the inpatient setting, however, is a lack of access to addiction medicine specialists.4-6

In 2017, we created a hospitalist-led interprofessional team called the B-Team (Buprenorphine Team) to help primary care teams identify patients with OUD, initiate and maintain buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization, provide warm handoffs to outpatient treatment programs, and reduce institutional stigma related to people with substance use disorders.

METHODS

Program Description

The B-Team is led by a hospital medicine physician assistant and includes physicians from internal medicine, consult-liaison psychiatry, and palliative care; advanced practice and bedside nurses; a social worker; a pharmacist; a chaplain; a peer-recovery specialist; and medical trainees. The B-Team is notified of potential candidates for buprenorphine through a secure texting platform, one that is accessible to any healthcare provider at the hospital. Patients who are referred to the B-Team either self-identify or are identified by their primary team as having an underlying OUD. One of the B-Team providers assesses the patient to determine if they are eligible to receive inpatient therapy. Patients are considered eligible for the program if they meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) criteria for OUD, have a desire to cease opioid use, and receive medical clearance to take buprenorphine.

For eligible patients, the B-Team provider orders a nurse-driven protocol to initiate buprenorphine for OUD. The chaplain offers psychospiritual counseling, and the social worker provides counseling and coordination of care. The B-Team partners with a nonhospital-affiliated, publicly-funded, office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) program that combines primary care with behavioral health programming. A follow-up outpatient appointment is secured prior to hospital discharge, and a member of the B-Team who has Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) X-waiver certification prescribes buprenorphine as a bridge until the follow-up appointment. The medication is dispensed from the hospital’s retail pharmacy, and the patient leaves the hospital with the medication in-hand.

Patients who are not eligible for buprenorphine therapy are offered a harm-reduction intervention or referral to the psychiatry consult liaison service to assess for alternative diagnoses or treatment. These patients are also offered psychospiritual counseling and a prescription for naloxone.

Prior to the creation of the B-Team at our hospital, there was no structure in place to facilitate initiation of buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization and no linkage to outpatient treatment after discharge; furthermore, none of the hospitalists or other providers (including consulting psychiatrists) had an X-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD.

Program Evaluation

Study data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture software. Inpatient and outpatient data were entered by a B-Team provider or a researcher via chart review. Patients were considered to be engaged in care if they attended at least one outpatient appointment for buprenorphine therapy during each of the following time periods: (1) 0 to 27 days (initial follow-up), 28-89 days (1- to 3-month follow-up), 90-179 days (3- to 6-month follow-up), and 180 days or more (>6-month follow-up). Only visits specifically for buprenorphine maintenance therapy were counted. If multiple encounters occurred within one time frame, the encounter closest to 0, 30, 90, or 180 days from discharge was used. If a patient did not attend any encounters during a specified time frame, they were considered to no longer be engaged in care and were no longer tracked for purposes of the evaluation. Data for the percentage of patients engaged in outpatient care are presented as the number of patients who attended at least one appointment during each of the follow-up periods (1 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, or after 6 months, as noted above) divided by the number of patients who had been discharged with coordinated follow-up.

The number of patients admitted per month for whom there was an order to initiate inpatient buprenorphine therapy was analyzed using a statistical process control chart,

This program and study were considered quality improvement by The University of Texas Institutional Review Board and did not meet criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

During the first 2 years of the program (September 2018-September 2020), the B-Team received 260 patient referrals. Most of the patients were White (72%), male (62%), and between ages 25 and 44 years (53%) (Appendix Table). The team initiated buprenorphine therapy in 132 hospitalized patients. In the year prior to the creation of the B-Team program, the average number of hospitalized patients receiving buprenorphine for OUD per month was three; after the launch of the B-Team program, this number increased

The B-Team saw a total of 132 eligible patients; members of the team provided counseling, support, and resources regarding buprenorphine therapy. In addition, the B-Team’s chaplain provided emotional support and spiritual connection (if desired) to 40 of these patients (30%). In the study, no cases of precipitated withdrawal were identified. Of the 132 patients seen, 110 (83%) were accepted to an outpatient OUD program upon discharge from the hospital; 98 (89%) of these patients were accepted at our partner OBOT clinic. The remaining patients were not interested in continuing OUD treatment (13%) or were denied acceptance to an outpatient program based on administrative and/or financial eligibility guidelines (4%). Patients who would not be attending an outpatient program were discontinued on buprenorphine therapy prior to discharge, counseled about naloxone, and provided printed resources.

Outpatient appointment attendance was used to measure ongoing treatment engagement of the 110 patients who were discharged with coordinated follow-up care. A total of 65 patients (59%) attended their first outpatient appointment; the average time between discharge and the first outpatient appointment was 5.9 days. Forty-two patients (38%) attended at least one appointment between 1 and 3 months; 29 (26%) between 3 and 6 months; and 24 (22%) after 6 months (Figure 2).

Of the 128 patients who were not administered buprenorphine therapy, 64 (50%) were not interested in starting treatment and/or were not ready to engage in treatment; 36 (28%) did not meet criteria for OUD treatment; 28 (22%) were already receiving treatment or preferred another type of OUD treatment; and 13 (10%) had severe comorbid addiction and/or illness requiring treatment that contraindicates the use of buprenorphine.

DISCUSSION

A volunteer hospitalist-led interprofessional team providing evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD was associated with a substantial increase in patients receiving buprenorphine therapy—both during hospitalization and after discharge. In the program, 59% of patients attended initial follow-up appointments, and 22% of patients were still engaged at 6 months. These outpatient follow-up rates appear to be similar to, or higher than, other programs described in the literature. For example, a buprenorphine OUD-treatment initiative led by the psychiatry consult service at a Boston academic medical center resulted in less than half of patients receiving buprenorphine treatment within 2 months of discharge.7 In another study wherein an addiction medicine consult service administered buprenorphine to patients with OUD during hospitalization, 39%, 27%, and 18% of patients were retained in outpatient treatment at 30, 90, and 180 days, respectively.8

The B-Team model is likely generalizable to other hospital medicine groups that may not otherwise have access to inpatient care for substance use disorder. The B-Team is not an addiction medicine consultation service; rather, it is a hospitalist-led quality improvement initiative seeking to improve the standard of care for hospitalized patients with OUD.

A significant barrier is ensuring ongoing support for patients with OUD after discharge. In the B-Team program, a parallel OBOT program was created by a local nonaffiliated federally qualified health center. Although 89% of patients received treatment at this OBOT clinic, the inpatient team also has relationships with other local treatment centers, including programs that provide methadone. Another important barrier to high-quality outpatient care for OUD is the requirement of an X-waiver. To help overcome this barrier, our inpatient program partnered with a regional medical society to offer periodic X-waiver training to outpatient providers. In less than a year, more than 100 regional prescribers participated in this program.

Our study has several limitations. There was likely some degree of selection bias among the hospitalized patients who received initial buprenorphine treatment. To our knowledge, there is no specific validated screening tool for OUD in the inpatient acute care setting; moreover, we have been unable to implement standardized screening for OUD into the electronic health record. As such, we rely on the totality of the clinical circumstances approach to identify patients with OUD.

Furthermore, we had neither a comparison group nor a prospective plan to follow patients who did not remain engaged in care after discharge. In addition, our analysis of OUD admissions included F11 ICD-10 codes, which are limited by clinical documentation.9,10 Our program focuses exclusively on buprenorphine initiation due to insufficient immediate outpatient capacity for methadone initiated during hospitalization and lack of coverage for extended-release naltrexone. Limitations to outpatient data-sharing prevented the reporting of outpatient appointments external to the identified partner program; since these appointments were included in the analysis as “lost to follow-up,” actual engagement rates may be higher than those reported.

Moving forward, the B-Team is continuing to serve as a role model for appropriate, patient-centered, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD. Attending physicians and residents with an X-waiver are now encouraged to initiate buprenorphine treatment on their own. In June 2020, we added peer-recovery support services to the program, which has improved care for patients and increased adoption of hospital-initiated substance use disorder interventions.11 Lessons learned from inpatient implementation are being applied to our hospital’s emergency department and to an inpatient obstetrics unit at a partner hospital; they are also being employed to further empower hospitalists to diagnose and treat other substance use disorders, such as alcohol use disorder.

Hospitalizations related to opioid use disorder (OUD) have increased and now account for up to 6% of hospital admissions in certain areas of the United States.1 Patients with OUD who are started on buprenorphine during hospitalization are more likely to enter outpatient treatment, stay in treatment longer, and have more drug-free days compared with patients who only receive a referral for outpatient treatment.2,3 Therefore, a crucial comprehensive strategy for OUD care should include hospital-based programs that support initiation of treatment in the inpatient setting and strong bridges to outpatient care. One of the common barriers to initiating treatment in the inpatient setting, however, is a lack of access to addiction medicine specialists.4-6

In 2017, we created a hospitalist-led interprofessional team called the B-Team (Buprenorphine Team) to help primary care teams identify patients with OUD, initiate and maintain buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization, provide warm handoffs to outpatient treatment programs, and reduce institutional stigma related to people with substance use disorders.

METHODS

Program Description

The B-Team is led by a hospital medicine physician assistant and includes physicians from internal medicine, consult-liaison psychiatry, and palliative care; advanced practice and bedside nurses; a social worker; a pharmacist; a chaplain; a peer-recovery specialist; and medical trainees. The B-Team is notified of potential candidates for buprenorphine through a secure texting platform, one that is accessible to any healthcare provider at the hospital. Patients who are referred to the B-Team either self-identify or are identified by their primary team as having an underlying OUD. One of the B-Team providers assesses the patient to determine if they are eligible to receive inpatient therapy. Patients are considered eligible for the program if they meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) criteria for OUD, have a desire to cease opioid use, and receive medical clearance to take buprenorphine.

For eligible patients, the B-Team provider orders a nurse-driven protocol to initiate buprenorphine for OUD. The chaplain offers psychospiritual counseling, and the social worker provides counseling and coordination of care. The B-Team partners with a nonhospital-affiliated, publicly-funded, office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) program that combines primary care with behavioral health programming. A follow-up outpatient appointment is secured prior to hospital discharge, and a member of the B-Team who has Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) X-waiver certification prescribes buprenorphine as a bridge until the follow-up appointment. The medication is dispensed from the hospital’s retail pharmacy, and the patient leaves the hospital with the medication in-hand.

Patients who are not eligible for buprenorphine therapy are offered a harm-reduction intervention or referral to the psychiatry consult liaison service to assess for alternative diagnoses or treatment. These patients are also offered psychospiritual counseling and a prescription for naloxone.

Prior to the creation of the B-Team at our hospital, there was no structure in place to facilitate initiation of buprenorphine therapy during hospitalization and no linkage to outpatient treatment after discharge; furthermore, none of the hospitalists or other providers (including consulting psychiatrists) had an X-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD.

Program Evaluation

Study data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture software. Inpatient and outpatient data were entered by a B-Team provider or a researcher via chart review. Patients were considered to be engaged in care if they attended at least one outpatient appointment for buprenorphine therapy during each of the following time periods: (1) 0 to 27 days (initial follow-up), 28-89 days (1- to 3-month follow-up), 90-179 days (3- to 6-month follow-up), and 180 days or more (>6-month follow-up). Only visits specifically for buprenorphine maintenance therapy were counted. If multiple encounters occurred within one time frame, the encounter closest to 0, 30, 90, or 180 days from discharge was used. If a patient did not attend any encounters during a specified time frame, they were considered to no longer be engaged in care and were no longer tracked for purposes of the evaluation. Data for the percentage of patients engaged in outpatient care are presented as the number of patients who attended at least one appointment during each of the follow-up periods (1 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, or after 6 months, as noted above) divided by the number of patients who had been discharged with coordinated follow-up.

The number of patients admitted per month for whom there was an order to initiate inpatient buprenorphine therapy was analyzed using a statistical process control chart,

This program and study were considered quality improvement by The University of Texas Institutional Review Board and did not meet criteria for human subjects research.

RESULTS

During the first 2 years of the program (September 2018-September 2020), the B-Team received 260 patient referrals. Most of the patients were White (72%), male (62%), and between ages 25 and 44 years (53%) (Appendix Table). The team initiated buprenorphine therapy in 132 hospitalized patients. In the year prior to the creation of the B-Team program, the average number of hospitalized patients receiving buprenorphine for OUD per month was three; after the launch of the B-Team program, this number increased

The B-Team saw a total of 132 eligible patients; members of the team provided counseling, support, and resources regarding buprenorphine therapy. In addition, the B-Team’s chaplain provided emotional support and spiritual connection (if desired) to 40 of these patients (30%). In the study, no cases of precipitated withdrawal were identified. Of the 132 patients seen, 110 (83%) were accepted to an outpatient OUD program upon discharge from the hospital; 98 (89%) of these patients were accepted at our partner OBOT clinic. The remaining patients were not interested in continuing OUD treatment (13%) or were denied acceptance to an outpatient program based on administrative and/or financial eligibility guidelines (4%). Patients who would not be attending an outpatient program were discontinued on buprenorphine therapy prior to discharge, counseled about naloxone, and provided printed resources.

Outpatient appointment attendance was used to measure ongoing treatment engagement of the 110 patients who were discharged with coordinated follow-up care. A total of 65 patients (59%) attended their first outpatient appointment; the average time between discharge and the first outpatient appointment was 5.9 days. Forty-two patients (38%) attended at least one appointment between 1 and 3 months; 29 (26%) between 3 and 6 months; and 24 (22%) after 6 months (Figure 2).

Of the 128 patients who were not administered buprenorphine therapy, 64 (50%) were not interested in starting treatment and/or were not ready to engage in treatment; 36 (28%) did not meet criteria for OUD treatment; 28 (22%) were already receiving treatment or preferred another type of OUD treatment; and 13 (10%) had severe comorbid addiction and/or illness requiring treatment that contraindicates the use of buprenorphine.

DISCUSSION

A volunteer hospitalist-led interprofessional team providing evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD was associated with a substantial increase in patients receiving buprenorphine therapy—both during hospitalization and after discharge. In the program, 59% of patients attended initial follow-up appointments, and 22% of patients were still engaged at 6 months. These outpatient follow-up rates appear to be similar to, or higher than, other programs described in the literature. For example, a buprenorphine OUD-treatment initiative led by the psychiatry consult service at a Boston academic medical center resulted in less than half of patients receiving buprenorphine treatment within 2 months of discharge.7 In another study wherein an addiction medicine consult service administered buprenorphine to patients with OUD during hospitalization, 39%, 27%, and 18% of patients were retained in outpatient treatment at 30, 90, and 180 days, respectively.8

The B-Team model is likely generalizable to other hospital medicine groups that may not otherwise have access to inpatient care for substance use disorder. The B-Team is not an addiction medicine consultation service; rather, it is a hospitalist-led quality improvement initiative seeking to improve the standard of care for hospitalized patients with OUD.

A significant barrier is ensuring ongoing support for patients with OUD after discharge. In the B-Team program, a parallel OBOT program was created by a local nonaffiliated federally qualified health center. Although 89% of patients received treatment at this OBOT clinic, the inpatient team also has relationships with other local treatment centers, including programs that provide methadone. Another important barrier to high-quality outpatient care for OUD is the requirement of an X-waiver. To help overcome this barrier, our inpatient program partnered with a regional medical society to offer periodic X-waiver training to outpatient providers. In less than a year, more than 100 regional prescribers participated in this program.

Our study has several limitations. There was likely some degree of selection bias among the hospitalized patients who received initial buprenorphine treatment. To our knowledge, there is no specific validated screening tool for OUD in the inpatient acute care setting; moreover, we have been unable to implement standardized screening for OUD into the electronic health record. As such, we rely on the totality of the clinical circumstances approach to identify patients with OUD.

Furthermore, we had neither a comparison group nor a prospective plan to follow patients who did not remain engaged in care after discharge. In addition, our analysis of OUD admissions included F11 ICD-10 codes, which are limited by clinical documentation.9,10 Our program focuses exclusively on buprenorphine initiation due to insufficient immediate outpatient capacity for methadone initiated during hospitalization and lack of coverage for extended-release naltrexone. Limitations to outpatient data-sharing prevented the reporting of outpatient appointments external to the identified partner program; since these appointments were included in the analysis as “lost to follow-up,” actual engagement rates may be higher than those reported.

Moving forward, the B-Team is continuing to serve as a role model for appropriate, patient-centered, evidence-based care for hospitalized patients with OUD. Attending physicians and residents with an X-waiver are now encouraged to initiate buprenorphine treatment on their own. In June 2020, we added peer-recovery support services to the program, which has improved care for patients and increased adoption of hospital-initiated substance use disorder interventions.11 Lessons learned from inpatient implementation are being applied to our hospital’s emergency department and to an inpatient obstetrics unit at a partner hospital; they are also being employed to further empower hospitalists to diagnose and treat other substance use disorders, such as alcohol use disorder.

1. Owens PL, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML. Hospital Burden of Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays: Metropolitan and Rural Hospitals, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #258. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2020. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559382/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK559382.pdf

2. Liebschutz J, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556

3. Moreno JL, Wakeman SE, Duprey MS, Roberts RJ, Jacobson JS, Devlin JW. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019;13(4):306-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000499

4. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736

5. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice — integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1606157

6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024

7. Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: a case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12161

8. Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007

9. Jicha C, Saxon D, Lofwall MR, Fanucchi LC. Substance use disorder assessment, diagnosis, and management for patients hospitalized with severe infections due to injection drug use. J Addict Med. 2019;13(1):69-74. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000454

10. Heslin KC, Owens PL, Karaca Z, Barrett ML, Moore BJ, Elixhauser A. Trends in opioid-related inpatient stays shifted after the US transitioned to ICD-10-CM diagnosis coding in 2015. Med Care. 2017;55(11):918-923. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000805

11. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

1. Owens PL, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML. Hospital Burden of Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays: Metropolitan and Rural Hospitals, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #258. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2020. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559382/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK559382.pdf

2. Liebschutz J, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556

3. Moreno JL, Wakeman SE, Duprey MS, Roberts RJ, Jacobson JS, Devlin JW. Predictors for 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission among patients with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2019;13(4):306-313. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000499

4. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736

5. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice — integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1606157

6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024

7. Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: a case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12161

8. Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007

9. Jicha C, Saxon D, Lofwall MR, Fanucchi LC. Substance use disorder assessment, diagnosis, and management for patients hospitalized with severe infections due to injection drug use. J Addict Med. 2019;13(1):69-74. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000454

10. Heslin KC, Owens PL, Karaca Z, Barrett ML, Moore BJ, Elixhauser A. Trends in opioid-related inpatient stays shifted after the US transitioned to ICD-10-CM diagnosis coding in 2015. Med Care. 2017;55(11):918-923. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000805

11. Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine