User login

My response to ACOG’s emphasis on vaginal hysterectomy first

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Recorded November 17, 2015, at the AAGL Global Congress in Las Vegas, Nevada.

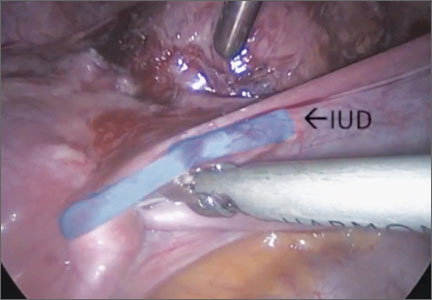

Surgical removal of malpositioned IUDs

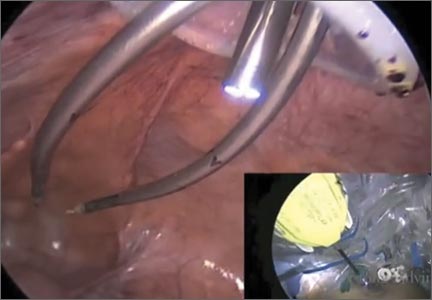

Today’s intrauterine devices (IUDs) represent an excellent form of long-acting reversible contraception. Depending on the type of IUD, many also are used to help alleviate such gynecologic symptoms as abnormal uterine bleeding. Approximately 10% of IUD insertions are complicated by malpositioning, which can include embedding, translocation, or perforation. Malpositioned IUDs are often amenable to office removal but, occasionally, hysteroscopy or laparoscopy is necessary.

In this video, we begin by reviewing techniques for complicated office IUD removal. Then we present 4 cases of malpositioned IUDs that required surgical intervention; hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, or combined techniques were used in each case. This video highlights how preoperative imaging often is not sufficient to determine the necessary surgical approach. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the potential need for hysteroscopy or laparoscopy to surgically remove a malpositioned IUD.

Although risk factors for malpositioned IUDs are not well studied in the literature, understanding proper placement and identification of complications at the time of IUD placement are essential to malpositioning prevention.

My colleagues and I hope you enjoy this video.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Today’s intrauterine devices (IUDs) represent an excellent form of long-acting reversible contraception. Depending on the type of IUD, many also are used to help alleviate such gynecologic symptoms as abnormal uterine bleeding. Approximately 10% of IUD insertions are complicated by malpositioning, which can include embedding, translocation, or perforation. Malpositioned IUDs are often amenable to office removal but, occasionally, hysteroscopy or laparoscopy is necessary.

In this video, we begin by reviewing techniques for complicated office IUD removal. Then we present 4 cases of malpositioned IUDs that required surgical intervention; hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, or combined techniques were used in each case. This video highlights how preoperative imaging often is not sufficient to determine the necessary surgical approach. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the potential need for hysteroscopy or laparoscopy to surgically remove a malpositioned IUD.

Although risk factors for malpositioned IUDs are not well studied in the literature, understanding proper placement and identification of complications at the time of IUD placement are essential to malpositioning prevention.

My colleagues and I hope you enjoy this video.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Today’s intrauterine devices (IUDs) represent an excellent form of long-acting reversible contraception. Depending on the type of IUD, many also are used to help alleviate such gynecologic symptoms as abnormal uterine bleeding. Approximately 10% of IUD insertions are complicated by malpositioning, which can include embedding, translocation, or perforation. Malpositioned IUDs are often amenable to office removal but, occasionally, hysteroscopy or laparoscopy is necessary.

In this video, we begin by reviewing techniques for complicated office IUD removal. Then we present 4 cases of malpositioned IUDs that required surgical intervention; hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, or combined techniques were used in each case. This video highlights how preoperative imaging often is not sufficient to determine the necessary surgical approach. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the potential need for hysteroscopy or laparoscopy to surgically remove a malpositioned IUD.

Although risk factors for malpositioned IUDs are not well studied in the literature, understanding proper placement and identification of complications at the time of IUD placement are essential to malpositioning prevention.

My colleagues and I hope you enjoy this video.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

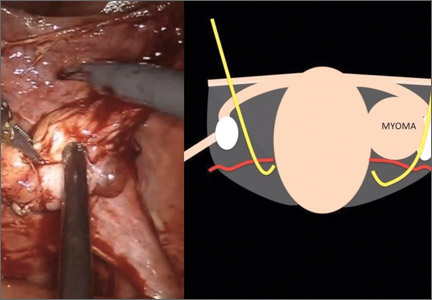

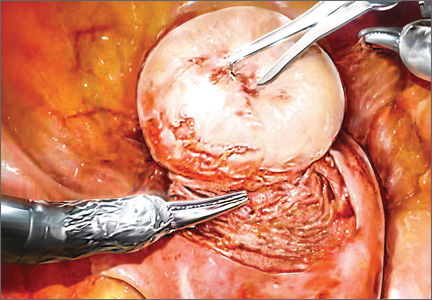

Surgical management of broad ligament fibroids

Although broad ligament fibroids are rare, their surgical management includes nuances of anatomical awareness, traction and counter-traction techniques, and proper hemostasis.

This month’s surgical video presents the case of a 40-year-old woman who presented to the emergency department with sudden-onset abdominal pain. She had a history of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea and had undergone uterine artery embolization.

The objectives of this technique video are to provide:

- an overview of the background, clinical presentation, and imaging related to broad ligament fibroids

- pertinent anatomical landmarks

- a clinical case of robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, demonstrating surgical technique

- key points for successful and safe surgical management.

I hope you find this video to be a useful tool for your practice and that you share it, and the other technique videos on my Video Channel, with your colleagues.

Although broad ligament fibroids are rare, their surgical management includes nuances of anatomical awareness, traction and counter-traction techniques, and proper hemostasis.

This month’s surgical video presents the case of a 40-year-old woman who presented to the emergency department with sudden-onset abdominal pain. She had a history of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea and had undergone uterine artery embolization.

The objectives of this technique video are to provide:

- an overview of the background, clinical presentation, and imaging related to broad ligament fibroids

- pertinent anatomical landmarks

- a clinical case of robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, demonstrating surgical technique

- key points for successful and safe surgical management.

I hope you find this video to be a useful tool for your practice and that you share it, and the other technique videos on my Video Channel, with your colleagues.

Although broad ligament fibroids are rare, their surgical management includes nuances of anatomical awareness, traction and counter-traction techniques, and proper hemostasis.

This month’s surgical video presents the case of a 40-year-old woman who presented to the emergency department with sudden-onset abdominal pain. She had a history of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea and had undergone uterine artery embolization.

The objectives of this technique video are to provide:

- an overview of the background, clinical presentation, and imaging related to broad ligament fibroids

- pertinent anatomical landmarks

- a clinical case of robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, demonstrating surgical technique

- key points for successful and safe surgical management.

I hope you find this video to be a useful tool for your practice and that you share it, and the other technique videos on my Video Channel, with your colleagues.

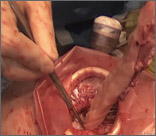

The Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique

As a result of recent concerns regarding the use of power morcellation, clinicians have been faced with the need to develop alternative techniques for contained tissue extraction during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures such as myomectomy and hysterectomy.

The following video represents a refined and reproducible approach that incorporates a containment bag (Anchor Medical) and a self-retaining retractor (Applied Medical) in order to meet the following objectives:

- tissue extraction without the need for power morcellation

- specimen containment to avoid intraperitoneal spillage

- ability to continue to offer minimally invasive surgical options to patients through a safe and standardized approach to tissue extraction.

The example case is real-time, contained, intact removal of an 8-cm, 130-g fibroid.

I hope you enjoy the featured opening session on best tissue extraction standards at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver and stop by to visit me at the OBG Management booth.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As a result of recent concerns regarding the use of power morcellation, clinicians have been faced with the need to develop alternative techniques for contained tissue extraction during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures such as myomectomy and hysterectomy.

The following video represents a refined and reproducible approach that incorporates a containment bag (Anchor Medical) and a self-retaining retractor (Applied Medical) in order to meet the following objectives:

- tissue extraction without the need for power morcellation

- specimen containment to avoid intraperitoneal spillage

- ability to continue to offer minimally invasive surgical options to patients through a safe and standardized approach to tissue extraction.

The example case is real-time, contained, intact removal of an 8-cm, 130-g fibroid.

I hope you enjoy the featured opening session on best tissue extraction standards at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver and stop by to visit me at the OBG Management booth.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As a result of recent concerns regarding the use of power morcellation, clinicians have been faced with the need to develop alternative techniques for contained tissue extraction during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures such as myomectomy and hysterectomy.

The following video represents a refined and reproducible approach that incorporates a containment bag (Anchor Medical) and a self-retaining retractor (Applied Medical) in order to meet the following objectives:

- tissue extraction without the need for power morcellation

- specimen containment to avoid intraperitoneal spillage

- ability to continue to offer minimally invasive surgical options to patients through a safe and standardized approach to tissue extraction.

The example case is real-time, contained, intact removal of an 8-cm, 130-g fibroid.

I hope you enjoy the featured opening session on best tissue extraction standards at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver and stop by to visit me at the OBG Management booth.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tissue extraction during minimally invasive Gyn surgery. Second of 2 Parts: Counseling the patient

In the absence of a definitive FDA decision on the future of power morcellation in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, many surgeons have stopped offering the option, often in response to constraints placed by their institutions, or have greatly expanded the informed consent discussion.

In Part 1 of this two-part roundtable discussion, which appeared in the September 2014 issue of OBG Management, our expert panelists discussed their current approach to tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy, as well as their preferred approach to both procedures amid this changing surgical environment. Here, in Part 2, they discuss patient counseling and the likely effects of FDA action.

How has your counseling changed?

OBG Management: Given recent concerns about the use of power morcellation, how has your counseling of the patient changed?

Kimberly Kho, MD, MPH: Though I look forward to the development of instruments and techniques that will make contained power morcellation safer, I am not using it currently and have been able to find minimally invasive alternatives such as minilaparotomy and vaginal removal of masses for the cases I would have considered for power morcellation.

Certainly, with power morcellation or any type of morcellation, it’s important to discuss the risks and benefits, as well as alternatives. Discussion should include the potential for:

- iatrogenic injury and tissue seeding of both benign and malignant tissue

- exacerbation of any occult malignancy and possible worsening of prognosis

- missing or mischaracterizing an occult malignancy.

Although there is no surefire way to avoid cellular dissemination with any type of surgery, I think it’s equally important to explain that, often, the only way to completely avoid fragmenting a large mass is to remove it en bloc, which would mean a large laparotomy for many patients. Women should understand the risks of laparotomy as well, including more frequent wound complications, longer hospitalization, and slower recovery.

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: If a clinician anticipates or plans the use of power morcellation, he or she certainly needs to go through an informed consent process with the patient. This process may include a separate form specific to power morcellation as well as detailed documentation during the preoperative visit.

OBG Management: What elements of the preoperative visit do you believe are important to document?

Dr. Advincula: It is important to clearly document the indications and alternatives for the surgery, as well as the decision-making process that led to the selection of a particular procedure and route of access. If any type of morcellation (power-driven or not) is anticipated, then the risks associated with it must be thoroughly discussed and documented in addition to the standard risks associated with any type of abdominal-pelvic surgery. No surgical procedure is without risks. Therefore, the process of informed consent cannot be taken lightly and is a critical part of the process that allows a patient to decide upon a particular intervention.

Jason D. Wright, MD: I believe the current role of power morcellation is limited. Patients considering the procedure should be counseled about the risks of cancer as well as other adverse pathologic abnormalities, including smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential, disseminated leiomyomatosis, and endometrial hyperplasia that may be associated with an occult cancer.

OBG Management: Do you recommend a separate consent form for power morcellation, as Dr. Advincula suggested?

Dr. Wright: Given the risk of adverse pathology, I think the role of electric power morcellation is limited. Patients should be carefully counseled about alternative surgical approaches that avoid tissue disruption and understand that the sensitivity of preoperative testing and intraoperative evaluation of smooth muscle neoplasms is limited. Further, patients considering contained morcellation also should be informed that the data examining the efficacy of these techniques are sparse.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: As I mentioned in Part 1 of our discussion, I’m giving patients new information about our concerns regarding occult malignancy, quoting the risk estimates given by the FDA this year.1 And the fact that we no longer use power morcellation at the Cleveland Clinic means that I no longer discuss it as an option, although one or two patients have asked for it in recent months.

I think many patients have read about it in the news or, once hysterectomy or myomectomy was planned, found discussion of the controversy surrounding it during their research. I’ve even had patients who underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy 2 or more years ago contacting me to find out whether power morcellation was used, and I have had to explain that hysteroscopic morcellation is different from the laparoscopic variant.

Patients are critical readers and are much more knowledgeable as a result of social media, so I do find myself spending more time discussing their procedure with them.

For myomectomy in particular, we send for a frozen section intraoperatively. Although that approach still is not 100% sensitive, it does guide what we do during surgery. If a sarcoma is found, for example, we call in the oncologists. I discuss that possibility with the patient as well. So I am spending more time with patients, but I don’t go into power morcellation because that is no longer an option for me.

OBG Management: Dr. Iglesia, has your counseling of patients changed in any way?

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I do not routinely use power morcellation. However, the findings from the FDA and Dr. Wright about the higher risk of occult malignancy in fibroids is information I share with patients preoperatively.1,2

For women with fibroids who want uterine conservation procedures or who desire medical management, such as focused ultrasound or uterine fibroid embolization, MRI is routine. However, we make patients aware that this imaging modality is not 100% sensitive in detecting occult cancer—and neither are random biopsies of fibroids. Patients also need to be made aware that treatment with fibroid embolization or other medical options also could delay the detection of cancer and sarcoma. Any morcellation technique (power, hand, vaginal) does have the risk of potential cancer spread and upstaging, so morcellation should not be used in any women with suspected or known malignancy.

Effects of likely FDA actions

OBG Management: If the FDA decides to ban power morcellation outright, in some ways the approach to patient counseling will be simpler, as one option will have been permanently eliminated. But if the FDA allows power morcellation to continue, with stricter labeling, would that affect how you counsel patients? And would you reconsider power morcellation in that light?

Dr. Kho: I think the current discussion has highlighted again how important the informed consent process is as an opportunity for information sharing. It’s an ongoing discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. It also offers us an opportunity to understand the patient’s values and perspectives throughout the process of surgical planning. So, no, I don’t think the FDA’s actions will change how I counsel patients. Regardless of the FDA’s decisions, I think open power morcellation as we currently know it may be obviated as new instruments for contained morcellation—as well as other techniques we’ve discussed—become more popular. But it’s critical that we meaningfully monitor these techniques for long-term safety. In order to make evidence-based decisions, we will need good data.

Dr. Iglesia: I cannot comment on a final FDA decision. However, my feeling is that any information that patients can use to become educated about treatment alternatives—including the risks and benefits of each option—will help inform and improve the shared decision-making process.

Dr. Advincula: Regardless of the verdict rendered by the FDA, the way we approach tissue extraction in minimally invasive surgery has been changed forever. It is always important to take a critical look at the way things are done, but not at the expense of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water. If power morcellation were to remain a viable option, my counseling would remain as is, as it already has been modified and quite detailed in the wake of this whole controversy. I still believe there is a role for power morcellation, albeit modified from its current iteration, when applied by the right physician in a properly evaluated patient with the right indication.

Summing up

OBG Management: Do you have any additional comments about this issue?

Dr. Advincula: The ability to accurately and reliably detect an occult uterine malignancy—specifically, leiomyosarcoma—is lacking at present. Whether or not power morcellation remains a viable option in the future, the bottom line is that patients will still present with occult uterine malignancy. Minimizing the mishandling of this unfortunate diagnosis will depend on sound clinical judgment as well as improvements in diagnosis. It always will be important to avoid blaming the lack of sound clinical practice on surgical devices that, when used appropriately, have the potential to benefit the majority of women.

Dr. Kho: The current attention on power morcellators presents an opportunity to improve upon our current practices and find solutions to the issues we are encountering. I think this is an exciting time for examining preoperative risk stratification, the innovation of new techniques, repopularization and improvement of older ones such as vaginal tissue extraction, and, overall, to improve our system of safety monitoring and surgical device surveillance.

Dr. Iglesia: Intraperitoneal power morcellation should not be used in cases of malignancy or suspected malignancy or in postmenopausal patients with bleeding or growing fibroids. The availability of power morcellators may be limited as manufacturers

cease distribution, hospitals ban use, or insurers refuse payment for use.

Alternative minimally invasive approaches—especially the transvaginal approach—should be considered, since there are fewer complications associated with vaginal surgery, especially compared with open and laparoscopic surgery.

Dr. Wright: Although electric power morcellation may allow some women to undergo a minimally invasive procedure, the data currently available clearly suggest that adverse pathology is more common in women who undergo morcellation than was previously thought.

Although the debate around morcellation has focused on leiomyosarcoma, epithelial endometrial tumors and other preinvasive abnormalities are also common. These unexpected pathologic findings in women who underwent electric power morcellation highlight the importance of performing more rigorous evaluation of new methods of tissue extraction.

Quick Poll:

If you are using, plan to use, or anticipate the possibility of using power morcellation during minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, does your consent process include a separate form specific to power morcellation?

Please provide your answer to this question in the Quick Poll on the OBG Management home page, and then see how your peers have voted. Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication.http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. Wright JD, Tergas AI, Burke WM, et al. Uterine pathology in women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy with morcellation [published online ahead of print July 22, 2014]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9005.

In the absence of a definitive FDA decision on the future of power morcellation in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, many surgeons have stopped offering the option, often in response to constraints placed by their institutions, or have greatly expanded the informed consent discussion.

In Part 1 of this two-part roundtable discussion, which appeared in the September 2014 issue of OBG Management, our expert panelists discussed their current approach to tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy, as well as their preferred approach to both procedures amid this changing surgical environment. Here, in Part 2, they discuss patient counseling and the likely effects of FDA action.

How has your counseling changed?

OBG Management: Given recent concerns about the use of power morcellation, how has your counseling of the patient changed?

Kimberly Kho, MD, MPH: Though I look forward to the development of instruments and techniques that will make contained power morcellation safer, I am not using it currently and have been able to find minimally invasive alternatives such as minilaparotomy and vaginal removal of masses for the cases I would have considered for power morcellation.

Certainly, with power morcellation or any type of morcellation, it’s important to discuss the risks and benefits, as well as alternatives. Discussion should include the potential for:

- iatrogenic injury and tissue seeding of both benign and malignant tissue

- exacerbation of any occult malignancy and possible worsening of prognosis

- missing or mischaracterizing an occult malignancy.

Although there is no surefire way to avoid cellular dissemination with any type of surgery, I think it’s equally important to explain that, often, the only way to completely avoid fragmenting a large mass is to remove it en bloc, which would mean a large laparotomy for many patients. Women should understand the risks of laparotomy as well, including more frequent wound complications, longer hospitalization, and slower recovery.

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: If a clinician anticipates or plans the use of power morcellation, he or she certainly needs to go through an informed consent process with the patient. This process may include a separate form specific to power morcellation as well as detailed documentation during the preoperative visit.

OBG Management: What elements of the preoperative visit do you believe are important to document?

Dr. Advincula: It is important to clearly document the indications and alternatives for the surgery, as well as the decision-making process that led to the selection of a particular procedure and route of access. If any type of morcellation (power-driven or not) is anticipated, then the risks associated with it must be thoroughly discussed and documented in addition to the standard risks associated with any type of abdominal-pelvic surgery. No surgical procedure is without risks. Therefore, the process of informed consent cannot be taken lightly and is a critical part of the process that allows a patient to decide upon a particular intervention.

Jason D. Wright, MD: I believe the current role of power morcellation is limited. Patients considering the procedure should be counseled about the risks of cancer as well as other adverse pathologic abnormalities, including smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential, disseminated leiomyomatosis, and endometrial hyperplasia that may be associated with an occult cancer.

OBG Management: Do you recommend a separate consent form for power morcellation, as Dr. Advincula suggested?

Dr. Wright: Given the risk of adverse pathology, I think the role of electric power morcellation is limited. Patients should be carefully counseled about alternative surgical approaches that avoid tissue disruption and understand that the sensitivity of preoperative testing and intraoperative evaluation of smooth muscle neoplasms is limited. Further, patients considering contained morcellation also should be informed that the data examining the efficacy of these techniques are sparse.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: As I mentioned in Part 1 of our discussion, I’m giving patients new information about our concerns regarding occult malignancy, quoting the risk estimates given by the FDA this year.1 And the fact that we no longer use power morcellation at the Cleveland Clinic means that I no longer discuss it as an option, although one or two patients have asked for it in recent months.

I think many patients have read about it in the news or, once hysterectomy or myomectomy was planned, found discussion of the controversy surrounding it during their research. I’ve even had patients who underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy 2 or more years ago contacting me to find out whether power morcellation was used, and I have had to explain that hysteroscopic morcellation is different from the laparoscopic variant.

Patients are critical readers and are much more knowledgeable as a result of social media, so I do find myself spending more time discussing their procedure with them.

For myomectomy in particular, we send for a frozen section intraoperatively. Although that approach still is not 100% sensitive, it does guide what we do during surgery. If a sarcoma is found, for example, we call in the oncologists. I discuss that possibility with the patient as well. So I am spending more time with patients, but I don’t go into power morcellation because that is no longer an option for me.

OBG Management: Dr. Iglesia, has your counseling of patients changed in any way?

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I do not routinely use power morcellation. However, the findings from the FDA and Dr. Wright about the higher risk of occult malignancy in fibroids is information I share with patients preoperatively.1,2

For women with fibroids who want uterine conservation procedures or who desire medical management, such as focused ultrasound or uterine fibroid embolization, MRI is routine. However, we make patients aware that this imaging modality is not 100% sensitive in detecting occult cancer—and neither are random biopsies of fibroids. Patients also need to be made aware that treatment with fibroid embolization or other medical options also could delay the detection of cancer and sarcoma. Any morcellation technique (power, hand, vaginal) does have the risk of potential cancer spread and upstaging, so morcellation should not be used in any women with suspected or known malignancy.

Effects of likely FDA actions

OBG Management: If the FDA decides to ban power morcellation outright, in some ways the approach to patient counseling will be simpler, as one option will have been permanently eliminated. But if the FDA allows power morcellation to continue, with stricter labeling, would that affect how you counsel patients? And would you reconsider power morcellation in that light?

Dr. Kho: I think the current discussion has highlighted again how important the informed consent process is as an opportunity for information sharing. It’s an ongoing discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. It also offers us an opportunity to understand the patient’s values and perspectives throughout the process of surgical planning. So, no, I don’t think the FDA’s actions will change how I counsel patients. Regardless of the FDA’s decisions, I think open power morcellation as we currently know it may be obviated as new instruments for contained morcellation—as well as other techniques we’ve discussed—become more popular. But it’s critical that we meaningfully monitor these techniques for long-term safety. In order to make evidence-based decisions, we will need good data.

Dr. Iglesia: I cannot comment on a final FDA decision. However, my feeling is that any information that patients can use to become educated about treatment alternatives—including the risks and benefits of each option—will help inform and improve the shared decision-making process.

Dr. Advincula: Regardless of the verdict rendered by the FDA, the way we approach tissue extraction in minimally invasive surgery has been changed forever. It is always important to take a critical look at the way things are done, but not at the expense of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water. If power morcellation were to remain a viable option, my counseling would remain as is, as it already has been modified and quite detailed in the wake of this whole controversy. I still believe there is a role for power morcellation, albeit modified from its current iteration, when applied by the right physician in a properly evaluated patient with the right indication.

Summing up

OBG Management: Do you have any additional comments about this issue?

Dr. Advincula: The ability to accurately and reliably detect an occult uterine malignancy—specifically, leiomyosarcoma—is lacking at present. Whether or not power morcellation remains a viable option in the future, the bottom line is that patients will still present with occult uterine malignancy. Minimizing the mishandling of this unfortunate diagnosis will depend on sound clinical judgment as well as improvements in diagnosis. It always will be important to avoid blaming the lack of sound clinical practice on surgical devices that, when used appropriately, have the potential to benefit the majority of women.

Dr. Kho: The current attention on power morcellators presents an opportunity to improve upon our current practices and find solutions to the issues we are encountering. I think this is an exciting time for examining preoperative risk stratification, the innovation of new techniques, repopularization and improvement of older ones such as vaginal tissue extraction, and, overall, to improve our system of safety monitoring and surgical device surveillance.

Dr. Iglesia: Intraperitoneal power morcellation should not be used in cases of malignancy or suspected malignancy or in postmenopausal patients with bleeding or growing fibroids. The availability of power morcellators may be limited as manufacturers

cease distribution, hospitals ban use, or insurers refuse payment for use.

Alternative minimally invasive approaches—especially the transvaginal approach—should be considered, since there are fewer complications associated with vaginal surgery, especially compared with open and laparoscopic surgery.

Dr. Wright: Although electric power morcellation may allow some women to undergo a minimally invasive procedure, the data currently available clearly suggest that adverse pathology is more common in women who undergo morcellation than was previously thought.

Although the debate around morcellation has focused on leiomyosarcoma, epithelial endometrial tumors and other preinvasive abnormalities are also common. These unexpected pathologic findings in women who underwent electric power morcellation highlight the importance of performing more rigorous evaluation of new methods of tissue extraction.

Quick Poll:

If you are using, plan to use, or anticipate the possibility of using power morcellation during minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, does your consent process include a separate form specific to power morcellation?

Please provide your answer to this question in the Quick Poll on the OBG Management home page, and then see how your peers have voted. Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In the absence of a definitive FDA decision on the future of power morcellation in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, many surgeons have stopped offering the option, often in response to constraints placed by their institutions, or have greatly expanded the informed consent discussion.

In Part 1 of this two-part roundtable discussion, which appeared in the September 2014 issue of OBG Management, our expert panelists discussed their current approach to tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy, as well as their preferred approach to both procedures amid this changing surgical environment. Here, in Part 2, they discuss patient counseling and the likely effects of FDA action.

How has your counseling changed?

OBG Management: Given recent concerns about the use of power morcellation, how has your counseling of the patient changed?

Kimberly Kho, MD, MPH: Though I look forward to the development of instruments and techniques that will make contained power morcellation safer, I am not using it currently and have been able to find minimally invasive alternatives such as minilaparotomy and vaginal removal of masses for the cases I would have considered for power morcellation.

Certainly, with power morcellation or any type of morcellation, it’s important to discuss the risks and benefits, as well as alternatives. Discussion should include the potential for:

- iatrogenic injury and tissue seeding of both benign and malignant tissue

- exacerbation of any occult malignancy and possible worsening of prognosis

- missing or mischaracterizing an occult malignancy.

Although there is no surefire way to avoid cellular dissemination with any type of surgery, I think it’s equally important to explain that, often, the only way to completely avoid fragmenting a large mass is to remove it en bloc, which would mean a large laparotomy for many patients. Women should understand the risks of laparotomy as well, including more frequent wound complications, longer hospitalization, and slower recovery.

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: If a clinician anticipates or plans the use of power morcellation, he or she certainly needs to go through an informed consent process with the patient. This process may include a separate form specific to power morcellation as well as detailed documentation during the preoperative visit.

OBG Management: What elements of the preoperative visit do you believe are important to document?

Dr. Advincula: It is important to clearly document the indications and alternatives for the surgery, as well as the decision-making process that led to the selection of a particular procedure and route of access. If any type of morcellation (power-driven or not) is anticipated, then the risks associated with it must be thoroughly discussed and documented in addition to the standard risks associated with any type of abdominal-pelvic surgery. No surgical procedure is without risks. Therefore, the process of informed consent cannot be taken lightly and is a critical part of the process that allows a patient to decide upon a particular intervention.

Jason D. Wright, MD: I believe the current role of power morcellation is limited. Patients considering the procedure should be counseled about the risks of cancer as well as other adverse pathologic abnormalities, including smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential, disseminated leiomyomatosis, and endometrial hyperplasia that may be associated with an occult cancer.

OBG Management: Do you recommend a separate consent form for power morcellation, as Dr. Advincula suggested?

Dr. Wright: Given the risk of adverse pathology, I think the role of electric power morcellation is limited. Patients should be carefully counseled about alternative surgical approaches that avoid tissue disruption and understand that the sensitivity of preoperative testing and intraoperative evaluation of smooth muscle neoplasms is limited. Further, patients considering contained morcellation also should be informed that the data examining the efficacy of these techniques are sparse.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: As I mentioned in Part 1 of our discussion, I’m giving patients new information about our concerns regarding occult malignancy, quoting the risk estimates given by the FDA this year.1 And the fact that we no longer use power morcellation at the Cleveland Clinic means that I no longer discuss it as an option, although one or two patients have asked for it in recent months.

I think many patients have read about it in the news or, once hysterectomy or myomectomy was planned, found discussion of the controversy surrounding it during their research. I’ve even had patients who underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy 2 or more years ago contacting me to find out whether power morcellation was used, and I have had to explain that hysteroscopic morcellation is different from the laparoscopic variant.

Patients are critical readers and are much more knowledgeable as a result of social media, so I do find myself spending more time discussing their procedure with them.

For myomectomy in particular, we send for a frozen section intraoperatively. Although that approach still is not 100% sensitive, it does guide what we do during surgery. If a sarcoma is found, for example, we call in the oncologists. I discuss that possibility with the patient as well. So I am spending more time with patients, but I don’t go into power morcellation because that is no longer an option for me.

OBG Management: Dr. Iglesia, has your counseling of patients changed in any way?

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I do not routinely use power morcellation. However, the findings from the FDA and Dr. Wright about the higher risk of occult malignancy in fibroids is information I share with patients preoperatively.1,2

For women with fibroids who want uterine conservation procedures or who desire medical management, such as focused ultrasound or uterine fibroid embolization, MRI is routine. However, we make patients aware that this imaging modality is not 100% sensitive in detecting occult cancer—and neither are random biopsies of fibroids. Patients also need to be made aware that treatment with fibroid embolization or other medical options also could delay the detection of cancer and sarcoma. Any morcellation technique (power, hand, vaginal) does have the risk of potential cancer spread and upstaging, so morcellation should not be used in any women with suspected or known malignancy.

Effects of likely FDA actions

OBG Management: If the FDA decides to ban power morcellation outright, in some ways the approach to patient counseling will be simpler, as one option will have been permanently eliminated. But if the FDA allows power morcellation to continue, with stricter labeling, would that affect how you counsel patients? And would you reconsider power morcellation in that light?

Dr. Kho: I think the current discussion has highlighted again how important the informed consent process is as an opportunity for information sharing. It’s an ongoing discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives. It also offers us an opportunity to understand the patient’s values and perspectives throughout the process of surgical planning. So, no, I don’t think the FDA’s actions will change how I counsel patients. Regardless of the FDA’s decisions, I think open power morcellation as we currently know it may be obviated as new instruments for contained morcellation—as well as other techniques we’ve discussed—become more popular. But it’s critical that we meaningfully monitor these techniques for long-term safety. In order to make evidence-based decisions, we will need good data.

Dr. Iglesia: I cannot comment on a final FDA decision. However, my feeling is that any information that patients can use to become educated about treatment alternatives—including the risks and benefits of each option—will help inform and improve the shared decision-making process.

Dr. Advincula: Regardless of the verdict rendered by the FDA, the way we approach tissue extraction in minimally invasive surgery has been changed forever. It is always important to take a critical look at the way things are done, but not at the expense of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water. If power morcellation were to remain a viable option, my counseling would remain as is, as it already has been modified and quite detailed in the wake of this whole controversy. I still believe there is a role for power morcellation, albeit modified from its current iteration, when applied by the right physician in a properly evaluated patient with the right indication.

Summing up

OBG Management: Do you have any additional comments about this issue?

Dr. Advincula: The ability to accurately and reliably detect an occult uterine malignancy—specifically, leiomyosarcoma—is lacking at present. Whether or not power morcellation remains a viable option in the future, the bottom line is that patients will still present with occult uterine malignancy. Minimizing the mishandling of this unfortunate diagnosis will depend on sound clinical judgment as well as improvements in diagnosis. It always will be important to avoid blaming the lack of sound clinical practice on surgical devices that, when used appropriately, have the potential to benefit the majority of women.

Dr. Kho: The current attention on power morcellators presents an opportunity to improve upon our current practices and find solutions to the issues we are encountering. I think this is an exciting time for examining preoperative risk stratification, the innovation of new techniques, repopularization and improvement of older ones such as vaginal tissue extraction, and, overall, to improve our system of safety monitoring and surgical device surveillance.

Dr. Iglesia: Intraperitoneal power morcellation should not be used in cases of malignancy or suspected malignancy or in postmenopausal patients with bleeding or growing fibroids. The availability of power morcellators may be limited as manufacturers

cease distribution, hospitals ban use, or insurers refuse payment for use.

Alternative minimally invasive approaches—especially the transvaginal approach—should be considered, since there are fewer complications associated with vaginal surgery, especially compared with open and laparoscopic surgery.

Dr. Wright: Although electric power morcellation may allow some women to undergo a minimally invasive procedure, the data currently available clearly suggest that adverse pathology is more common in women who undergo morcellation than was previously thought.

Although the debate around morcellation has focused on leiomyosarcoma, epithelial endometrial tumors and other preinvasive abnormalities are also common. These unexpected pathologic findings in women who underwent electric power morcellation highlight the importance of performing more rigorous evaluation of new methods of tissue extraction.

Quick Poll:

If you are using, plan to use, or anticipate the possibility of using power morcellation during minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, does your consent process include a separate form specific to power morcellation?

Please provide your answer to this question in the Quick Poll on the OBG Management home page, and then see how your peers have voted. Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication.http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. Wright JD, Tergas AI, Burke WM, et al. Uterine pathology in women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy with morcellation [published online ahead of print July 22, 2014]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9005.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication.http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. Wright JD, Tergas AI, Burke WM, et al. Uterine pathology in women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy with morcellation [published online ahead of print July 22, 2014]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9005.

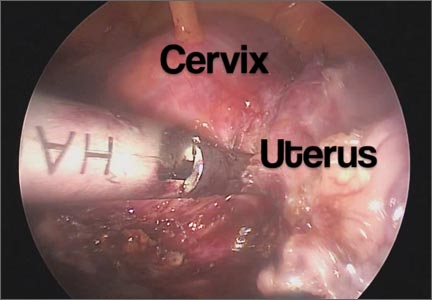

Total laparoscopic versus laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy

It gives me great pleasure to introduce this month’s surgical video. The following feature presentation was produced by my third-year fellow, Mireille Truong, MD, and my third-year resident, Sarah Horvath, MD. The focus of this surgical video is to compare and contrast total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH). The indication for the TLH case was refractory dysmenorrhea and for the LSH case was as part of a concomitant sacrocervicopexy. The particular methods for specimen removal demonstrated include through the colpotomy for TLH and cold knife manual morcellation within a bag using an Alexis retractor for LSH.

The objectives of this surgical video are to:

- Highlight the clinical advantages and disadvantages between cervical removal or retention at the time of a minimally invasive laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Demonstrate the surgical nuances between TLH and LSH

- Provide a potential resource for patient counseling as well as medical student and resident education.

I encourage you to share this video as an educational resource with your colleagues, residents, students, and patients alike.

I hope to see you at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver, November 17–21, 2014. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

It gives me great pleasure to introduce this month’s surgical video. The following feature presentation was produced by my third-year fellow, Mireille Truong, MD, and my third-year resident, Sarah Horvath, MD. The focus of this surgical video is to compare and contrast total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH). The indication for the TLH case was refractory dysmenorrhea and for the LSH case was as part of a concomitant sacrocervicopexy. The particular methods for specimen removal demonstrated include through the colpotomy for TLH and cold knife manual morcellation within a bag using an Alexis retractor for LSH.

The objectives of this surgical video are to:

- Highlight the clinical advantages and disadvantages between cervical removal or retention at the time of a minimally invasive laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Demonstrate the surgical nuances between TLH and LSH

- Provide a potential resource for patient counseling as well as medical student and resident education.

I encourage you to share this video as an educational resource with your colleagues, residents, students, and patients alike.

I hope to see you at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver, November 17–21, 2014. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

It gives me great pleasure to introduce this month’s surgical video. The following feature presentation was produced by my third-year fellow, Mireille Truong, MD, and my third-year resident, Sarah Horvath, MD. The focus of this surgical video is to compare and contrast total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH). The indication for the TLH case was refractory dysmenorrhea and for the LSH case was as part of a concomitant sacrocervicopexy. The particular methods for specimen removal demonstrated include through the colpotomy for TLH and cold knife manual morcellation within a bag using an Alexis retractor for LSH.

The objectives of this surgical video are to:

- Highlight the clinical advantages and disadvantages between cervical removal or retention at the time of a minimally invasive laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Demonstrate the surgical nuances between TLH and LSH

- Provide a potential resource for patient counseling as well as medical student and resident education.

I encourage you to share this video as an educational resource with your colleagues, residents, students, and patients alike.

I hope to see you at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver, November 17–21, 2014. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

— Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

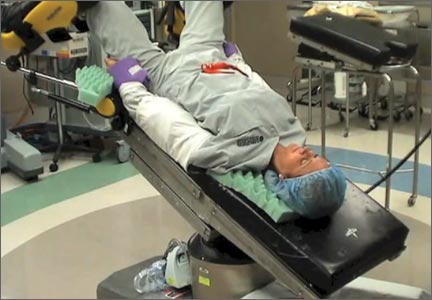

Preventing postoperative neuropathies: Patient positioning for minimally invasive procedures

In this comprehensive educational video we review appropriate patient positioning for laparoscopic and robotic surgery to prevent postoperative neuropathies that can be experienced with gynecologic surgery. We also include a case-based review of injuries specific to the brachial plexus, ulnar nerve, and femoral nerve.

Our technique involves the use of a bed sheet, an egg crate foam mattress pad, and boot-type stirrups. We recommend setting up the operating room table to facilitate tucking of the patient’s arms and to prevent slippage of the patient when she is placed in steep Trendelenburg. For all steps involved, see the video.

Tips for setting up the operating room bed include:

- Use of a single bed sheet placed across the head of a bare table with an egg crate foam mattress pad over the sheet to prevent the need for strapping the patient to the bed or the use of shoulder braces to prevent slippage.

- For low dorsal lithotomy positioning, flex the patient’s hips with a trunk-to-thigh angle of approximately 170°, and never more than 180°.

- For arm tucking, remove the arm boards and excess egg crate foam from the patient’s side and placecushioning over the elbow and the wrist. Keep the patient’s hand pronated when tucking and do not allow the arm to hang over the side of the bed.

- If the patient is obese, support the tucked arm by placing the arm boards beneath the arm parallel to the bed.

Next month we continue our series on surgical techniques with a video on why choosing the proper colpotomy cup is critical for successful minimally invasive hysterectomy.

Will you be joining me at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver this November? Safe patient positioning for minimally invasive surgery and other exciting topics will be discussed. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this comprehensive educational video we review appropriate patient positioning for laparoscopic and robotic surgery to prevent postoperative neuropathies that can be experienced with gynecologic surgery. We also include a case-based review of injuries specific to the brachial plexus, ulnar nerve, and femoral nerve.

Our technique involves the use of a bed sheet, an egg crate foam mattress pad, and boot-type stirrups. We recommend setting up the operating room table to facilitate tucking of the patient’s arms and to prevent slippage of the patient when she is placed in steep Trendelenburg. For all steps involved, see the video.

Tips for setting up the operating room bed include:

- Use of a single bed sheet placed across the head of a bare table with an egg crate foam mattress pad over the sheet to prevent the need for strapping the patient to the bed or the use of shoulder braces to prevent slippage.

- For low dorsal lithotomy positioning, flex the patient’s hips with a trunk-to-thigh angle of approximately 170°, and never more than 180°.

- For arm tucking, remove the arm boards and excess egg crate foam from the patient’s side and placecushioning over the elbow and the wrist. Keep the patient’s hand pronated when tucking and do not allow the arm to hang over the side of the bed.

- If the patient is obese, support the tucked arm by placing the arm boards beneath the arm parallel to the bed.

Next month we continue our series on surgical techniques with a video on why choosing the proper colpotomy cup is critical for successful minimally invasive hysterectomy.

Will you be joining me at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver this November? Safe patient positioning for minimally invasive surgery and other exciting topics will be discussed. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this comprehensive educational video we review appropriate patient positioning for laparoscopic and robotic surgery to prevent postoperative neuropathies that can be experienced with gynecologic surgery. We also include a case-based review of injuries specific to the brachial plexus, ulnar nerve, and femoral nerve.

Our technique involves the use of a bed sheet, an egg crate foam mattress pad, and boot-type stirrups. We recommend setting up the operating room table to facilitate tucking of the patient’s arms and to prevent slippage of the patient when she is placed in steep Trendelenburg. For all steps involved, see the video.

Tips for setting up the operating room bed include:

- Use of a single bed sheet placed across the head of a bare table with an egg crate foam mattress pad over the sheet to prevent the need for strapping the patient to the bed or the use of shoulder braces to prevent slippage.

- For low dorsal lithotomy positioning, flex the patient’s hips with a trunk-to-thigh angle of approximately 170°, and never more than 180°.

- For arm tucking, remove the arm boards and excess egg crate foam from the patient’s side and placecushioning over the elbow and the wrist. Keep the patient’s hand pronated when tucking and do not allow the arm to hang over the side of the bed.

- If the patient is obese, support the tucked arm by placing the arm boards beneath the arm parallel to the bed.

Next month we continue our series on surgical techniques with a video on why choosing the proper colpotomy cup is critical for successful minimally invasive hysterectomy.

Will you be joining me at the AAGL Global Congress on Minimally Invasive Gynecology in Vancouver this November? Safe patient positioning for minimally invasive surgery and other exciting topics will be discussed. Visit www.aagl.org/globalcongress for more information.

—Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Understanding the spectrum of multiport and single-site robotics for hysterectomy

We present this video with the objective of demonstrating a hysterectomy performed using the robotic single-site approach in juxtaposition with a robotic multiport hysterectomy. In the video, and briefly here, we review the benefits, disadvantages, and challenges of robotic single-site hysterectomy.

The advantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- possible improved aesthetics for the patient

- allowance for surgeon independence while minimizing the need for a bedside assistant

- automatic reassignment of the robotic arm controls

- circumvention of certain limitations seen in laparoscopic single-site procedures.

The disadvantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- instrumentation is nonwristed and less robust than that of multiport instrumentation

- decreased degrees of freedom

- longer suturing time

- restricted assistant port use

- decreased applicability to a wide range of procedures as the surgical approach is limited to less complex and smaller pathology.

Related articles:

The robot is broadly accessible less than 10 years after its introduction to gynecologic surgery. Janelle Yates (News for your Practice; December 2013)

The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it? Arnold P. Advincula MD; Cheryl B. Iglesia MD; Rosanne M. Kho MD; Jamal Mourad, DO; Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD; Jason D. Wright, MD (Roundtable; April 2013)

Identify your learning curve for robotic hysterectomy. Joshua L Woelk, MD, MS, and John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Guest Editorial; April 2013)

In general, each step of the single-port procedure has been found to be equivalent in time to a multiport approach to robotic-assisted hysterectomy—except for the step of vaginal cuff closure. Since the initial experience, aside from overcoming the learning curve of a new surgical approach, various techniques have been modified in order to surmount this challenge, such as closing the vaginal cuff vertically, using a cutting needle versus a tapered needle, addition of a “plus one” wristed multiport robotic arm, or replacing the single-site robotic needle driver with a multiport 5-mm needle driver.

Nevertheless, widespread adoption of single-site robotic gynecologic surgery still requires further technological improvements, and further research and experience is needed to determine its role, benefits, and applications in gynecologic surgery.

--Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

We present this video with the objective of demonstrating a hysterectomy performed using the robotic single-site approach in juxtaposition with a robotic multiport hysterectomy. In the video, and briefly here, we review the benefits, disadvantages, and challenges of robotic single-site hysterectomy.

The advantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- possible improved aesthetics for the patient

- allowance for surgeon independence while minimizing the need for a bedside assistant

- automatic reassignment of the robotic arm controls

- circumvention of certain limitations seen in laparoscopic single-site procedures.

The disadvantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- instrumentation is nonwristed and less robust than that of multiport instrumentation

- decreased degrees of freedom

- longer suturing time

- restricted assistant port use

- decreased applicability to a wide range of procedures as the surgical approach is limited to less complex and smaller pathology.

Related articles:

The robot is broadly accessible less than 10 years after its introduction to gynecologic surgery. Janelle Yates (News for your Practice; December 2013)

The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it? Arnold P. Advincula MD; Cheryl B. Iglesia MD; Rosanne M. Kho MD; Jamal Mourad, DO; Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD; Jason D. Wright, MD (Roundtable; April 2013)

Identify your learning curve for robotic hysterectomy. Joshua L Woelk, MD, MS, and John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Guest Editorial; April 2013)

In general, each step of the single-port procedure has been found to be equivalent in time to a multiport approach to robotic-assisted hysterectomy—except for the step of vaginal cuff closure. Since the initial experience, aside from overcoming the learning curve of a new surgical approach, various techniques have been modified in order to surmount this challenge, such as closing the vaginal cuff vertically, using a cutting needle versus a tapered needle, addition of a “plus one” wristed multiport robotic arm, or replacing the single-site robotic needle driver with a multiport 5-mm needle driver.

Nevertheless, widespread adoption of single-site robotic gynecologic surgery still requires further technological improvements, and further research and experience is needed to determine its role, benefits, and applications in gynecologic surgery.

--Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

We present this video with the objective of demonstrating a hysterectomy performed using the robotic single-site approach in juxtaposition with a robotic multiport hysterectomy. In the video, and briefly here, we review the benefits, disadvantages, and challenges of robotic single-site hysterectomy.

The advantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- possible improved aesthetics for the patient

- allowance for surgeon independence while minimizing the need for a bedside assistant

- automatic reassignment of the robotic arm controls

- circumvention of certain limitations seen in laparoscopic single-site procedures.

The disadvantages of single-site robotic hysterectomy include:

- instrumentation is nonwristed and less robust than that of multiport instrumentation

- decreased degrees of freedom

- longer suturing time

- restricted assistant port use

- decreased applicability to a wide range of procedures as the surgical approach is limited to less complex and smaller pathology.

Related articles:

The robot is broadly accessible less than 10 years after its introduction to gynecologic surgery. Janelle Yates (News for your Practice; December 2013)

The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it? Arnold P. Advincula MD; Cheryl B. Iglesia MD; Rosanne M. Kho MD; Jamal Mourad, DO; Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD; Jason D. Wright, MD (Roundtable; April 2013)

Identify your learning curve for robotic hysterectomy. Joshua L Woelk, MD, MS, and John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Guest Editorial; April 2013)

In general, each step of the single-port procedure has been found to be equivalent in time to a multiport approach to robotic-assisted hysterectomy—except for the step of vaginal cuff closure. Since the initial experience, aside from overcoming the learning curve of a new surgical approach, various techniques have been modified in order to surmount this challenge, such as closing the vaginal cuff vertically, using a cutting needle versus a tapered needle, addition of a “plus one” wristed multiport robotic arm, or replacing the single-site robotic needle driver with a multiport 5-mm needle driver.

Nevertheless, widespread adoption of single-site robotic gynecologic surgery still requires further technological improvements, and further research and experience is needed to determine its role, benefits, and applications in gynecologic surgery.

--Dr. Arnold Advincula, AAGL 2014 Scientific Program Chair

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

Tips and techniques for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy

CASE: IS OPEN MYOMECTOMY THE BEST OPTION FOR THIS PATIENT?

In her only pregnancy, a 34-year-old patient experienced a spontaneous first-trimester loss and underwent dilation and curettage. She had noted an increase in her abdominal girth, as well as pelvic pressure, but had attributed both to the pregnancy. Three months after the pregnancy loss, however, neither had resolved. Because she hopes to conceive again and deliver a healthy infant, the patient consulted a gynecologist. After ultrasonography revealed multiple fibroids, that physician recommended open myomectomy. The patient, a Jehovah’s Witness, comes to your office for a second opinion.

On physical examination, she has a 16-weeks’ sized irregular uterus with the cervix displaced behind the pubic symphysis. T2 weighted scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis in the sagittal view reveal multiple subserosal and intramural fibroids that displace, but do not involve, the uterine cavity (FIGURE 2). The MRI results confirm that the uterus extends beyond the pelvis above the sacral promontory, the fundus lies a few centimeters below the umbilicus, and there is no evidence of adenomyosis. The patient’s hemoglobin level is normal (12.2 g/dL).

What surgical approach would you recommend?

Endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, MRI-guided focused ultrasound, hysterectomy, and myomectomy are all treatments for symptomatic uterine fibroids. For women desiring uterine preservation and future fertility, however, myomectomy is the preferred option of many experts.

Myomectomy traditionally has been performed via an open laparotomy approach. With the rise of minimally invasive surgery in gynecology, safe endoscopic surgical approaches and techniques have evolved.

The EndoWrist technology from the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) provides increased instrument range of motion, enabling the surgeon to mimic open surgical technique, thereby simplifying the technical challenges of conventional laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying. However, this technology does not minimize or simplify the challenges that leiomyomas can pose, including enucleation (FIGURE 1). Although it has facilitated the progression and adoption of endoscopic myomectomy, the da Vinci system requires an experienced gynecologic endoscopic surgeon.

In this article, we outline the essential steps and offer some clinical surgical pearls to make robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy a systematic, safe, and efficient procedure.

Benefits of the robotic approach

Compared with open abdominal myomectomy, the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach is associated with less blood loss, lower complication rates, and shorter hospitalization.1 A retrospective case study from the Cleveland Clinic confirmed these findings when investigators compared surgical outcomes between the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach, standard laparoscopy, and open myomectomy.2 In an assessment of 575 cases (393 open, 93 laparoscopic, and 89 robot-assisted laparoscopic), they found the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach to be associated with the removal of significantly larger myomas (vs standard laparoscopy), as well as lower blood loss and shorter hospitalization (vs open myomectomy).2

Related Article: The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it?

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is critical

Careful patient selection and thorough preoperative assessment are the cornerstones of successful robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Among the variables that should be considered in selecting patients are uterine size, the patient’s body habitus, and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Size of the uterus, body habitus, and laxity of the abdominal wall all influence the surgeon’s ability to create the necessary operating space. Intraperitoneal space is required during myomectomy because of the need to apply traction and countertraction during enucleation of fibroids. If the necessary space cannot be obtained, a minilaparotomy technique is one alternative. This technique, described by Glasser, limits the skin incision to 3 to 6 cm in myomectomies for large fibroids that can be accessed easily anteriorly.3

Number and location of fibroids. Women with a solitary fibroid, a few dominant fibroids, or multiple pedunculated fibroids are excellent candidates for an endoscopic approach. Although there are no limits on the number of fibroids that can be removed, women with what we have termed “miliary fibroids,” or multiple fibroids disseminated throughout the entire myometrium, with very little normal myometrium, are poor surgical candidates. Not only does the presence of these fibroids leave some concern about the functional ability of the remaining myometrium in pregnancy, but it may be technically difficult to adequately resect all of the critical fibroids and reapproximate the myometrial defects.

The consistency of fibroids also affects the ease of the enucleation process during myomectomy. Due to the soft, spongy nature of degenerating fibroids and their tendency to fragment and shred when manipulated, these cases are more challenging and should not be attempted without a solid foundation of surgical experience.

MRI serves several purposes

Fibroids can be localized and identified as pedunculated, subserosal, intramural, or submucosal via MRI. Measurements and spatial orientation of the fibroids within the uterus can be formulated using T2 weighted coronal, axial, and sagittal images.

The risk of entering the uterine cavity, as well as the risk of synechiae, may be significantly greater if leiomyomas abut and distort the cavity. Surgical strategies, such as planning the location of the hysterotomy or the inclusion of other procedures (eg, hysteroscopic resection for type 0 or type 1 submucosal fibroids), can be formulated with the information provided by MRI. In cases involving multiple fibroids or intramural fibroids, in particular, MRI serves as a surgical “treasure map” or “GPS.” Preoperative MRI is also one way to offset the lack of haptic feedback during surgery to locate the myomas for removal. As we mentioned earlier, important characteristics, such as degeneration or calcification, also can be readily observed on MRI.

Most important, MRI can distinguish adenomyosis from leiomyomas. Adenomyosis can mimic leiomyomas—both clinically and on sonographic imaging—particularly when it is focal in nature. MRI can make the distinction between these two entities so that patients can be counseled appropriately.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Use a uterine manipulator

This device will facilitate the enucleation process, providing another focal point for traction and countertraction. A variety of uterine manipulators are available. We use the Advincula Arch (Cooper Surgical, Trumball, Connecticut) in conjunction with the Uterine Positioning System (Cooper Surgical). The latter attaches to the operating table and to the Advincula Arch to secure the uterus in a steady position throughout the procedure.

During enucleation, the manipulator is crucial to hold the uterus within the pelvis and the field of vision and to act as countertraction as traction is applied to the fibroid.

Individualize port placement

Rather than premeasure port placement on the abdomen, we individualize it, based on a variety of characteristics, including body habitus and uterine pathology (FIGURE 3). However, we follow some basic principles:

- We insert a Veress needle through the umbilicus to achieve pneumoperitoneum

- After insufflation, we use an upper quadrant entry (right or left, depending on which side the robot patient side cart is docked) under direct visualization using a 5-mm laparoscope and optical trocar. This entry will serve as the assistant port for surgery.

- Before placing the rest of the ports under direct visualization, relative to uterine pathology, we elevate the uterus out of the pelvis. This step ensures that enough distance is placed between the camera and the instrument arms to adequately visualize and perform the surgery.

- In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, a supraumbilical camera port often is necessary.

- We generally employ a four-arm technique using a 12-mm Xcel trocar (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Blue Ash, Ohio) that is 150 mm in length for the camera port, three 8-mm telerobotic trocar ports, and a 5-mm Airseal trocar (SurgiQuest, Orange, Connecticut) for the assistant port. There should be at least one hand’s breadth between the ports to minimize arm collision and maximize range of motion.

- Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), we strongly recommend, and exclusively use, the longest length for the camera. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

- We generally use the following wristed robotic instruments to perform myomectomy: tenaculum, monopolar scissors, and PlasmaKinetic (PK) bipolar forceps.

Inject vasopressin into the myometrium

Vasopressin causes vasospasm and uterine muscle contraction and decreases blood loss during myomectomy. It should be diluted (20 U in 50–200 mL of normal saline), introduced with a 7-inch, 22-gauge spinal needle through the anterior abdominal wall, and injected into the myometrium and serosa overlying the fibroid (VIDEO 1 and VIDEO 2).

Perform this step with care, with aspiration prior to injection, to avoid intravascular injection. Although vasopressin is safe overall, serious complications and rare cases of life-threatening hypotension, pulmonary edema, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest have been reported after the injection of as little as 3 U into the myometrium.4–7

Relative contraindications to vasopressin, such as hypertension, should be discussed with anesthesia prior to use of the drug during surgery.

Enucleate the fibroid

Although either a vertical or a horizontal-transverse incision can be made overlying the uterus, a transverse incision allows for technical optimization of wristed movements for suturing and efficient closure. Whenever possible, therefore, we favor a transverse hysterotomy.

During enucleation, keep the use of thermal energy to a minimum. The same holds true for the uterine incision, although its length can be extended as needed.

Using the wristed robotic tenaculum (or an assistant using a laparoscopic tenaculum or corkscrew), grasp and elevate the myoma away from the fixed uterus (FIGURE 1). This step is not intended to enucleate the myoma through force, but to apply traction and position the fibroid to best delineate and present the leading edge of the pseudocapsule that lies between the myoma and the myometrium. Dissection then can proceed using a “push and spread” technique, bluntly separating the natural plane between the fibroid and the myometrium. Occasionally, fibrous attachments of the pseudocapsule can be transected sharply using the bipolar forceps and monopolar scissors.

Again, we encourage the intermittent use of minimal thermal energy to facilitate this process and achieve temporary hemostasis. As the dissection progresses, the fibroid can be regrasped closer to its leading edge, causing the myoma to be rolled out (VIDEO 3 and VIDEO 4).

Close the myometrium We advocate multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma (VIDEO 5).