User login

2023 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

It has been an incredible year for complex gynecology and minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), with several outstanding new findings and reviews in 2023. The surgical community continues to push the envelope and emphasize the value of this specialty for women’s health.

Endometriosis and adenomyosis were at the center of several large cohort studies and systematic reviews that reassessed what we know about how to evaluate and treat these challenging diseases, including both surgical and nonsurgical approaches, with an emphasis on fertility-sparing modalities.1-8 In addition, a focus on quality of life, patient-centered care, and racial biases allowed us to reflect on our own practice patterns and keep the patient at the center of care models.9-13 Finally, there was a clear expansion in the use of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for care and novel minimally invasive tools.14

In this Update, we highlight and expand on how several particularly important developments are likely to make a difference in our clinical management.

New classification system for cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with defined surgical guidance has 97% treatment success rate

Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005113

A large multiarmed study by Ban and colleagues used multivariable modeling to formulate and test a classification system and recommended surgical treatment strategies for patients with a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSP).15 In the study, 273 patients were included in the predictive modeling group, 118 in the internal validation group, and 564 within the model testing cohort. Classifications were based on 2 independent risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: anterior myometrial thickness and mean diameter of gestational sac (MSD).

Classification types

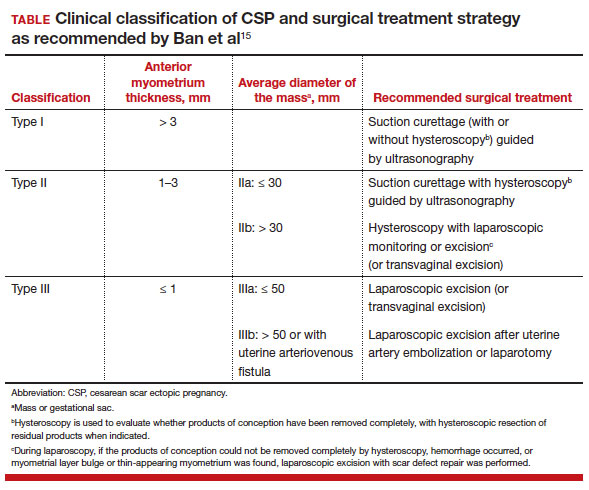

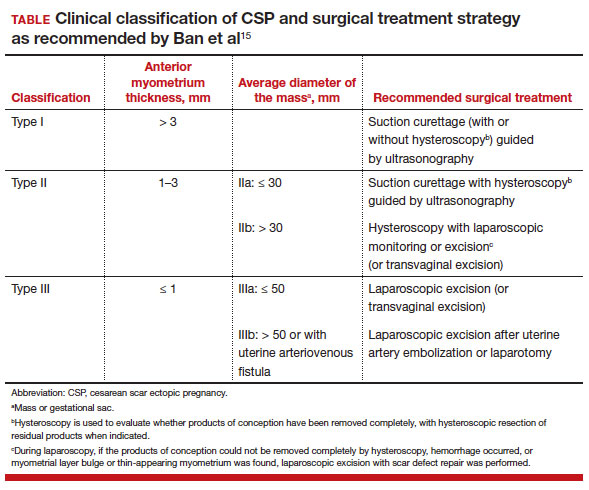

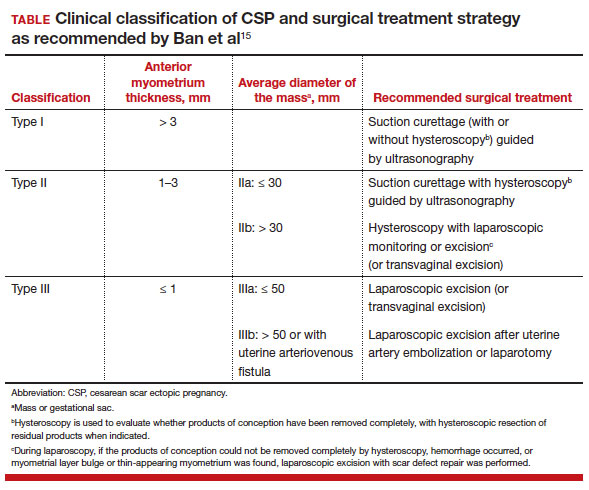

The 3 main CSP types were defined based on the anterior myometrial thickness at the cesarean section scar (type I, > 3 mm; type II, 1–3 mm; type III, ≤ 1 mm) and subtyped based on the MSD (type IIa, MSD ≤ 30 mm; type IIb, MSD > 30 mm; type IIIa, MSD ≤ 50 mm; type IIIb, MSD > 50 mm).

The subgroups were matched with recommended surgical strategy using expert opinion: Type I CSP was treated with suction dilation and aspiration (D&A) under ultrasound guidance, with or without hysteroscopy. Type IIa CSP was treated with suction D&A with hysteroscopy under ultrasound guidance. Type IIb CSP was treated with hysteroscopy with laparoscopic monitoring or excision, or transvaginal excision. Type IIIa CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision or transvaginal excision. Type IIIb CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision after uterine artery embolization or laparotomy (TABLE).15

Treatment outcomes

These guidelines were tested on a cohort of 564 patients between 2014 and 2022. Using these treatment guidelines, the overall treatment success rate was 97.5%; 85% of patients had a negative serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level within 3 weeks, and 95.2% of patients resumed menstrual cycles within 8 weeks. Successful treatment was defined as:

- complete resection of the products of conception

- no need to shift to a second-line surgical strategy

- no major complications

- no readmission for additional treatment

- serum ß-hCG levels that returned to normal within 4 weeks.

Although the incidence of CSP is reported to be around 1:2,000 pregnancies, these rare findings frequently cause a clinical conundrum.16 This thoughtful study by Ban and colleagues provides guidance with the creation of a classification system aimed at decreasing the severe morbidity that can come from mismanagement of these problematic pregnancies using predictive quantitative measures. In our own practice, we have used classification (type 1 endogenic or type 2 exogenic), mean gestational sac diameter, and overlying myometrial thickness when weighing options for treatment. However, decisions have been made on a case-by-case basis and expert opinion without specific cutoffs. Having defined parameters to more accurately classify the type of ectopic pregnancy is essential for communicating risk factors with all team members and for research purposes. The treatment algorithm proposed and tested in this study is logical with good outcomes in the test group. We applaud the authors of this study on a rare but potentially morbid pregnancy outcome. Of note, this study does not discuss nonsurgical alternatives for treatment, such as intra-sac methotrexate injection, which is another option used in select patients at our institution.

Continue to: Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications...

Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications

Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

In a large European multicenter retrospective cohort study, Casarin and colleagues evaluated perioperative complications during laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis or adenomyosis in 995 patients treated from 2010 to 2020.2

Reported intraoperative data included the frequency of ureterolysis (26.8%), deep nodule resection (30%) and posterior adhesiolysis (38.9%), unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (15.1%), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (26.8%), estimated blood loss (mean, 100 mL), and adverse events. Intraoperative complications occurred in 3% of cases (including bladder/bowel injury or need for transfusion).

Postoperative complications occurred in 13.8% of cases, and 9.3% had a major event, including vaginal cuff dehiscence, fever, abscess, and fistula.

Factors associated with postoperative complications

In a multivariate analysis, the authors found that increased operative time, younger age at surgery, previous surgery for endometriosis, and occurrence of intraoperative complications were associated with Clavien-Dindo score grade 2 or greater postoperative complications.

Medical treatment for endometriosis with estro-progestin or progestin medications, however, was found to be protective, with an odds ratio of 0.50 (95% confidence interval, 0.31–0.81).

It is well known that endometriosis is a risk factor for surgical complications. The reported complication rates in this cohort were relatively high, with nearly 10% of patients sustaining a major event postoperatively. While surgical risk is multifactorial and includes factors that are difficult to capture, including surgeon experience and patient population baseline risk, the relatively high incidence reported should be cause for pause and be incorporated in patient counseling. Of note, this cohort did undergo a large number of higher order dissections and a high number of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies (26.8%), which suggests a high-risk population.

What we found most interesting, however, was the positive finding that medication administration was protective against complications. The authors suggested that the antiinflammatory effects of hormone suppressive medications may be the key. Although this was a retrospective cohort study, the significant risk reduction seen is extremely compelling. A randomized clinical trial corroborating these findings would be instrumental. Endometriosis acts similarly to cancer in its progressive spread and destruction of surrounding tissues. As is increasingly supported in the oncologic literature, perhaps neoadjuvant therapy should be the standard for our “benign” high-risk endometriosis surgeries, with hormonal suppression serving as our chemotherapy. In our own practices, we may be more likely to encourage preoperative medication management, citing this added benefit to patients.

Diaphragmatic endometriosis prevalence higher than previously reported

Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.01.006

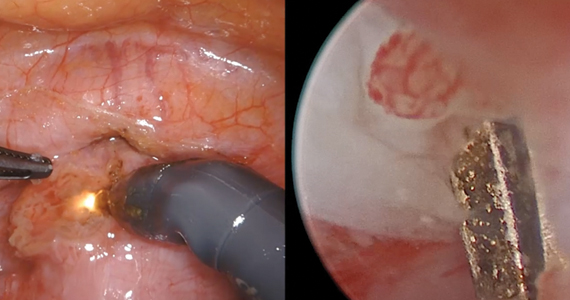

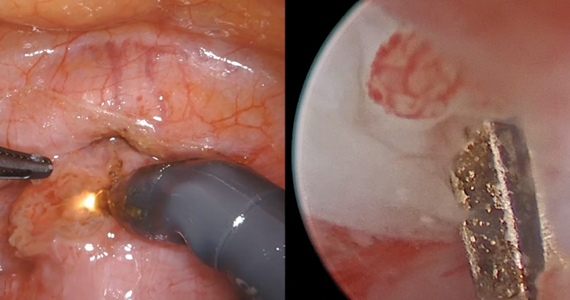

Pagano and colleagues conducted an impressive large prospective cohort study that included more than 1,300 patients with histologically proven endometriosis.1 Each patient underwent a systematic evaluation and reporting of intraoperative findings, including bilateral evaluation for diaphragmatic endometriosis (DE).

Patients with DE had high rates of infertility and high-stage disease

In this cohort, 4.7% of patients were found to have diaphragmatic disease; 92.3% of these cases had DE involving the right diaphragm. Patients with DE had a higher rate of infertility than those without DE (nearly 50%), but otherwise they had no difference in typical endometriosis symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysuria). In this cohort, 27.4% had diaphragmatic symptoms (right shoulder pain, cough, cyclic dyspnea).

Patients found to have DE had higher rates of stage III/IV disease (78.4%), and the left pelvis was affected in more patients (73.8%).

The prevalence of DE in this large cohort evaluated by endometriosis surgeons was far higher than previously reported rates of DE (0.19%–1.5% for abdominal endometriosis cases).17,18 Although admittedly this center cares for a larger portion of women with high-stage disease than many nonspecialty centers do, it still begs the question: Are we as a specialty underdiagnosing diaphragmatic endometriosis, especially in our patients with more severe endometriosis? Because nearly 5% of endometriosis patients could have DE, a thoughtful and systematic approach to the abdominal survey and diaphragm should be performed for each case. Adding questions about diaphragmatic symptoms to our preoperative evaluation may help to identify about one-quarter of these complicated patients preoperatively to aid in counseling and surgical planning. Patients to be specifically mindful about include those with high-stage disease, especially left-sided disease, and those with infertility (although this could be a secondary association given the larger proportion of patients with stage III/IV disease with infertility, and no multivariate analysis was performed). This study serves as a thoughtful reminder of this important subject.

A word on fertility-sparing treatments for adenomyosis

Several interesting and thoughtful studies were published on the fertility-sparing management of adenomyosis.6-8 These included a comparison of fertility outcomes following excisional and nonexcisional therapies,6 a systematic review of the literature that compared recurrence rates following procedural and surgical treatments,8 and outcomes after use of a novel therapy (percutaneous microwave ablation) for the treatment of adenomyosis.7

Although our critical evaluation of these studies found that they are not robust enough to yet change our practice, we want to applaud the authors on their discerning questions and on taking the initial steps to answer critical questions, including:

- What is the best uterine-sparing method for treatment of diffuse adenomyosis?

- Are radiofrequency or microwave ablation procedures the future of adenomyosis care?

- How do we counsel patients about fertility potential following procedural treatments?

- Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2023.01.006

- Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

- Abrao MS, Andres MP, Gingold JA, et al. Preoperative ultrasound scoring of endometriosis by AAGL 2021 endometriosis classification is concordant with laparoscopic surgical findings and distinguishes early from advanced stages. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:363-373. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2022.11.003

- Meyer R, Siedhoff M, Truong M, et al. Risk factors for major complications following minimally invasive surgeries for endometriosis in the United States. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:820-826. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.06.002

- Davenport S, Smith D, Green DJ. Barriers to a timely diagnosis of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:571-583. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005255

- Jiang L, Han Y, Song Z, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after uterus-sparing operative treatment for adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023:30:543-554. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.015

- Li S, Li Z, Lin M, et al. Efficacy of transabdominal ultrasoundguided percutaneous microwave ablation in the treatment of symptomatic adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:137-146. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.11.004

- Liu L, Tian H, Lin D, et al. Risk of recurrence and reintervention after uterine-sparing interventions for symptomatic adenomyosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:711-723. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005080

- Chang OH, Tewari S, Yao M, et al. Who places high value on the uterus? A cross-sectional survey study evaluating predictors for uterine preservation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:131-136. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.10.012

- Carey ET, Moore KJ, McClurg AB, et al. Racial disparities in hysterectomy route for benign disease: examining trends and perioperative complications from 2007 to 2018 using the NSQIP database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:627-634. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.024

- Frisch EH, Mitchell J, Yao M, et al. The impact of fertility goals on long-term quality of life in reproductive-aged women who underwent myomectomy versus hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:642-651. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.04.003 1

- Robinson WR, Mathias JG, Wood ME, et al. Ethnoracial differences in premenopausal hysterectomy: the role of symptom severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:350-359. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005225

- Harris HR, Peres LC, Johnson CE, et al. Racial differences in the association of endometriosis and uterine leiomyomas with the risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:11241138. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005191

- Atia O, Hazan E, Rotem R, et al. A scoring system developed by a machine learning algorithm to better predict adnexal torsion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:486-493. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.02.008

- Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005113

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1373-1381. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218690.24494.ce

- Scioscia M, Bruni F, Ceccaroni M, et al. Distribution of endometriotic lesions in endometriosis stage IV supports the menstrual reflux theory and requires specific preoperative assessment and therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:136-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01008.x

- Wetzel A, Philip C-A, Golfier F, et al. Surgical management of diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis: a French multicentric descriptive study. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102147. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102147

It has been an incredible year for complex gynecology and minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), with several outstanding new findings and reviews in 2023. The surgical community continues to push the envelope and emphasize the value of this specialty for women’s health.

Endometriosis and adenomyosis were at the center of several large cohort studies and systematic reviews that reassessed what we know about how to evaluate and treat these challenging diseases, including both surgical and nonsurgical approaches, with an emphasis on fertility-sparing modalities.1-8 In addition, a focus on quality of life, patient-centered care, and racial biases allowed us to reflect on our own practice patterns and keep the patient at the center of care models.9-13 Finally, there was a clear expansion in the use of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for care and novel minimally invasive tools.14

In this Update, we highlight and expand on how several particularly important developments are likely to make a difference in our clinical management.

New classification system for cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with defined surgical guidance has 97% treatment success rate

Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005113

A large multiarmed study by Ban and colleagues used multivariable modeling to formulate and test a classification system and recommended surgical treatment strategies for patients with a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSP).15 In the study, 273 patients were included in the predictive modeling group, 118 in the internal validation group, and 564 within the model testing cohort. Classifications were based on 2 independent risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: anterior myometrial thickness and mean diameter of gestational sac (MSD).

Classification types

The 3 main CSP types were defined based on the anterior myometrial thickness at the cesarean section scar (type I, > 3 mm; type II, 1–3 mm; type III, ≤ 1 mm) and subtyped based on the MSD (type IIa, MSD ≤ 30 mm; type IIb, MSD > 30 mm; type IIIa, MSD ≤ 50 mm; type IIIb, MSD > 50 mm).

The subgroups were matched with recommended surgical strategy using expert opinion: Type I CSP was treated with suction dilation and aspiration (D&A) under ultrasound guidance, with or without hysteroscopy. Type IIa CSP was treated with suction D&A with hysteroscopy under ultrasound guidance. Type IIb CSP was treated with hysteroscopy with laparoscopic monitoring or excision, or transvaginal excision. Type IIIa CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision or transvaginal excision. Type IIIb CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision after uterine artery embolization or laparotomy (TABLE).15

Treatment outcomes

These guidelines were tested on a cohort of 564 patients between 2014 and 2022. Using these treatment guidelines, the overall treatment success rate was 97.5%; 85% of patients had a negative serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level within 3 weeks, and 95.2% of patients resumed menstrual cycles within 8 weeks. Successful treatment was defined as:

- complete resection of the products of conception

- no need to shift to a second-line surgical strategy

- no major complications

- no readmission for additional treatment

- serum ß-hCG levels that returned to normal within 4 weeks.

Although the incidence of CSP is reported to be around 1:2,000 pregnancies, these rare findings frequently cause a clinical conundrum.16 This thoughtful study by Ban and colleagues provides guidance with the creation of a classification system aimed at decreasing the severe morbidity that can come from mismanagement of these problematic pregnancies using predictive quantitative measures. In our own practice, we have used classification (type 1 endogenic or type 2 exogenic), mean gestational sac diameter, and overlying myometrial thickness when weighing options for treatment. However, decisions have been made on a case-by-case basis and expert opinion without specific cutoffs. Having defined parameters to more accurately classify the type of ectopic pregnancy is essential for communicating risk factors with all team members and for research purposes. The treatment algorithm proposed and tested in this study is logical with good outcomes in the test group. We applaud the authors of this study on a rare but potentially morbid pregnancy outcome. Of note, this study does not discuss nonsurgical alternatives for treatment, such as intra-sac methotrexate injection, which is another option used in select patients at our institution.

Continue to: Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications...

Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications

Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

In a large European multicenter retrospective cohort study, Casarin and colleagues evaluated perioperative complications during laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis or adenomyosis in 995 patients treated from 2010 to 2020.2

Reported intraoperative data included the frequency of ureterolysis (26.8%), deep nodule resection (30%) and posterior adhesiolysis (38.9%), unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (15.1%), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (26.8%), estimated blood loss (mean, 100 mL), and adverse events. Intraoperative complications occurred in 3% of cases (including bladder/bowel injury or need for transfusion).

Postoperative complications occurred in 13.8% of cases, and 9.3% had a major event, including vaginal cuff dehiscence, fever, abscess, and fistula.

Factors associated with postoperative complications

In a multivariate analysis, the authors found that increased operative time, younger age at surgery, previous surgery for endometriosis, and occurrence of intraoperative complications were associated with Clavien-Dindo score grade 2 or greater postoperative complications.

Medical treatment for endometriosis with estro-progestin or progestin medications, however, was found to be protective, with an odds ratio of 0.50 (95% confidence interval, 0.31–0.81).

It is well known that endometriosis is a risk factor for surgical complications. The reported complication rates in this cohort were relatively high, with nearly 10% of patients sustaining a major event postoperatively. While surgical risk is multifactorial and includes factors that are difficult to capture, including surgeon experience and patient population baseline risk, the relatively high incidence reported should be cause for pause and be incorporated in patient counseling. Of note, this cohort did undergo a large number of higher order dissections and a high number of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies (26.8%), which suggests a high-risk population.

What we found most interesting, however, was the positive finding that medication administration was protective against complications. The authors suggested that the antiinflammatory effects of hormone suppressive medications may be the key. Although this was a retrospective cohort study, the significant risk reduction seen is extremely compelling. A randomized clinical trial corroborating these findings would be instrumental. Endometriosis acts similarly to cancer in its progressive spread and destruction of surrounding tissues. As is increasingly supported in the oncologic literature, perhaps neoadjuvant therapy should be the standard for our “benign” high-risk endometriosis surgeries, with hormonal suppression serving as our chemotherapy. In our own practices, we may be more likely to encourage preoperative medication management, citing this added benefit to patients.

Diaphragmatic endometriosis prevalence higher than previously reported

Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.01.006

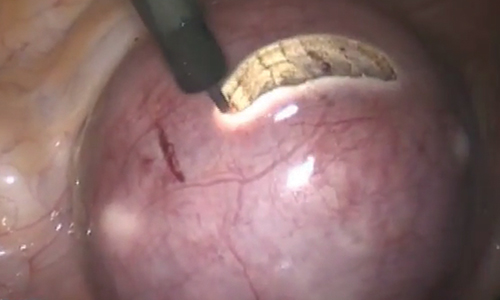

Pagano and colleagues conducted an impressive large prospective cohort study that included more than 1,300 patients with histologically proven endometriosis.1 Each patient underwent a systematic evaluation and reporting of intraoperative findings, including bilateral evaluation for diaphragmatic endometriosis (DE).

Patients with DE had high rates of infertility and high-stage disease

In this cohort, 4.7% of patients were found to have diaphragmatic disease; 92.3% of these cases had DE involving the right diaphragm. Patients with DE had a higher rate of infertility than those without DE (nearly 50%), but otherwise they had no difference in typical endometriosis symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysuria). In this cohort, 27.4% had diaphragmatic symptoms (right shoulder pain, cough, cyclic dyspnea).

Patients found to have DE had higher rates of stage III/IV disease (78.4%), and the left pelvis was affected in more patients (73.8%).

The prevalence of DE in this large cohort evaluated by endometriosis surgeons was far higher than previously reported rates of DE (0.19%–1.5% for abdominal endometriosis cases).17,18 Although admittedly this center cares for a larger portion of women with high-stage disease than many nonspecialty centers do, it still begs the question: Are we as a specialty underdiagnosing diaphragmatic endometriosis, especially in our patients with more severe endometriosis? Because nearly 5% of endometriosis patients could have DE, a thoughtful and systematic approach to the abdominal survey and diaphragm should be performed for each case. Adding questions about diaphragmatic symptoms to our preoperative evaluation may help to identify about one-quarter of these complicated patients preoperatively to aid in counseling and surgical planning. Patients to be specifically mindful about include those with high-stage disease, especially left-sided disease, and those with infertility (although this could be a secondary association given the larger proportion of patients with stage III/IV disease with infertility, and no multivariate analysis was performed). This study serves as a thoughtful reminder of this important subject.

A word on fertility-sparing treatments for adenomyosis

Several interesting and thoughtful studies were published on the fertility-sparing management of adenomyosis.6-8 These included a comparison of fertility outcomes following excisional and nonexcisional therapies,6 a systematic review of the literature that compared recurrence rates following procedural and surgical treatments,8 and outcomes after use of a novel therapy (percutaneous microwave ablation) for the treatment of adenomyosis.7

Although our critical evaluation of these studies found that they are not robust enough to yet change our practice, we want to applaud the authors on their discerning questions and on taking the initial steps to answer critical questions, including:

- What is the best uterine-sparing method for treatment of diffuse adenomyosis?

- Are radiofrequency or microwave ablation procedures the future of adenomyosis care?

- How do we counsel patients about fertility potential following procedural treatments?

It has been an incredible year for complex gynecology and minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), with several outstanding new findings and reviews in 2023. The surgical community continues to push the envelope and emphasize the value of this specialty for women’s health.

Endometriosis and adenomyosis were at the center of several large cohort studies and systematic reviews that reassessed what we know about how to evaluate and treat these challenging diseases, including both surgical and nonsurgical approaches, with an emphasis on fertility-sparing modalities.1-8 In addition, a focus on quality of life, patient-centered care, and racial biases allowed us to reflect on our own practice patterns and keep the patient at the center of care models.9-13 Finally, there was a clear expansion in the use of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for care and novel minimally invasive tools.14

In this Update, we highlight and expand on how several particularly important developments are likely to make a difference in our clinical management.

New classification system for cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy with defined surgical guidance has 97% treatment success rate

Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005113

A large multiarmed study by Ban and colleagues used multivariable modeling to formulate and test a classification system and recommended surgical treatment strategies for patients with a cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSP).15 In the study, 273 patients were included in the predictive modeling group, 118 in the internal validation group, and 564 within the model testing cohort. Classifications were based on 2 independent risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: anterior myometrial thickness and mean diameter of gestational sac (MSD).

Classification types

The 3 main CSP types were defined based on the anterior myometrial thickness at the cesarean section scar (type I, > 3 mm; type II, 1–3 mm; type III, ≤ 1 mm) and subtyped based on the MSD (type IIa, MSD ≤ 30 mm; type IIb, MSD > 30 mm; type IIIa, MSD ≤ 50 mm; type IIIb, MSD > 50 mm).

The subgroups were matched with recommended surgical strategy using expert opinion: Type I CSP was treated with suction dilation and aspiration (D&A) under ultrasound guidance, with or without hysteroscopy. Type IIa CSP was treated with suction D&A with hysteroscopy under ultrasound guidance. Type IIb CSP was treated with hysteroscopy with laparoscopic monitoring or excision, or transvaginal excision. Type IIIa CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision or transvaginal excision. Type IIIb CSP was treated with laparoscopic excision after uterine artery embolization or laparotomy (TABLE).15

Treatment outcomes

These guidelines were tested on a cohort of 564 patients between 2014 and 2022. Using these treatment guidelines, the overall treatment success rate was 97.5%; 85% of patients had a negative serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level within 3 weeks, and 95.2% of patients resumed menstrual cycles within 8 weeks. Successful treatment was defined as:

- complete resection of the products of conception

- no need to shift to a second-line surgical strategy

- no major complications

- no readmission for additional treatment

- serum ß-hCG levels that returned to normal within 4 weeks.

Although the incidence of CSP is reported to be around 1:2,000 pregnancies, these rare findings frequently cause a clinical conundrum.16 This thoughtful study by Ban and colleagues provides guidance with the creation of a classification system aimed at decreasing the severe morbidity that can come from mismanagement of these problematic pregnancies using predictive quantitative measures. In our own practice, we have used classification (type 1 endogenic or type 2 exogenic), mean gestational sac diameter, and overlying myometrial thickness when weighing options for treatment. However, decisions have been made on a case-by-case basis and expert opinion without specific cutoffs. Having defined parameters to more accurately classify the type of ectopic pregnancy is essential for communicating risk factors with all team members and for research purposes. The treatment algorithm proposed and tested in this study is logical with good outcomes in the test group. We applaud the authors of this study on a rare but potentially morbid pregnancy outcome. Of note, this study does not discuss nonsurgical alternatives for treatment, such as intra-sac methotrexate injection, which is another option used in select patients at our institution.

Continue to: Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications...

Pre-op hormonal treatment of endometriosis found to be protective against post-op complications

Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

In a large European multicenter retrospective cohort study, Casarin and colleagues evaluated perioperative complications during laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis or adenomyosis in 995 patients treated from 2010 to 2020.2

Reported intraoperative data included the frequency of ureterolysis (26.8%), deep nodule resection (30%) and posterior adhesiolysis (38.9%), unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (15.1%), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (26.8%), estimated blood loss (mean, 100 mL), and adverse events. Intraoperative complications occurred in 3% of cases (including bladder/bowel injury or need for transfusion).

Postoperative complications occurred in 13.8% of cases, and 9.3% had a major event, including vaginal cuff dehiscence, fever, abscess, and fistula.

Factors associated with postoperative complications

In a multivariate analysis, the authors found that increased operative time, younger age at surgery, previous surgery for endometriosis, and occurrence of intraoperative complications were associated with Clavien-Dindo score grade 2 or greater postoperative complications.

Medical treatment for endometriosis with estro-progestin or progestin medications, however, was found to be protective, with an odds ratio of 0.50 (95% confidence interval, 0.31–0.81).

It is well known that endometriosis is a risk factor for surgical complications. The reported complication rates in this cohort were relatively high, with nearly 10% of patients sustaining a major event postoperatively. While surgical risk is multifactorial and includes factors that are difficult to capture, including surgeon experience and patient population baseline risk, the relatively high incidence reported should be cause for pause and be incorporated in patient counseling. Of note, this cohort did undergo a large number of higher order dissections and a high number of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies (26.8%), which suggests a high-risk population.

What we found most interesting, however, was the positive finding that medication administration was protective against complications. The authors suggested that the antiinflammatory effects of hormone suppressive medications may be the key. Although this was a retrospective cohort study, the significant risk reduction seen is extremely compelling. A randomized clinical trial corroborating these findings would be instrumental. Endometriosis acts similarly to cancer in its progressive spread and destruction of surrounding tissues. As is increasingly supported in the oncologic literature, perhaps neoadjuvant therapy should be the standard for our “benign” high-risk endometriosis surgeries, with hormonal suppression serving as our chemotherapy. In our own practices, we may be more likely to encourage preoperative medication management, citing this added benefit to patients.

Diaphragmatic endometriosis prevalence higher than previously reported

Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.01.006

Pagano and colleagues conducted an impressive large prospective cohort study that included more than 1,300 patients with histologically proven endometriosis.1 Each patient underwent a systematic evaluation and reporting of intraoperative findings, including bilateral evaluation for diaphragmatic endometriosis (DE).

Patients with DE had high rates of infertility and high-stage disease

In this cohort, 4.7% of patients were found to have diaphragmatic disease; 92.3% of these cases had DE involving the right diaphragm. Patients with DE had a higher rate of infertility than those without DE (nearly 50%), but otherwise they had no difference in typical endometriosis symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysuria). In this cohort, 27.4% had diaphragmatic symptoms (right shoulder pain, cough, cyclic dyspnea).

Patients found to have DE had higher rates of stage III/IV disease (78.4%), and the left pelvis was affected in more patients (73.8%).

The prevalence of DE in this large cohort evaluated by endometriosis surgeons was far higher than previously reported rates of DE (0.19%–1.5% for abdominal endometriosis cases).17,18 Although admittedly this center cares for a larger portion of women with high-stage disease than many nonspecialty centers do, it still begs the question: Are we as a specialty underdiagnosing diaphragmatic endometriosis, especially in our patients with more severe endometriosis? Because nearly 5% of endometriosis patients could have DE, a thoughtful and systematic approach to the abdominal survey and diaphragm should be performed for each case. Adding questions about diaphragmatic symptoms to our preoperative evaluation may help to identify about one-quarter of these complicated patients preoperatively to aid in counseling and surgical planning. Patients to be specifically mindful about include those with high-stage disease, especially left-sided disease, and those with infertility (although this could be a secondary association given the larger proportion of patients with stage III/IV disease with infertility, and no multivariate analysis was performed). This study serves as a thoughtful reminder of this important subject.

A word on fertility-sparing treatments for adenomyosis

Several interesting and thoughtful studies were published on the fertility-sparing management of adenomyosis.6-8 These included a comparison of fertility outcomes following excisional and nonexcisional therapies,6 a systematic review of the literature that compared recurrence rates following procedural and surgical treatments,8 and outcomes after use of a novel therapy (percutaneous microwave ablation) for the treatment of adenomyosis.7

Although our critical evaluation of these studies found that they are not robust enough to yet change our practice, we want to applaud the authors on their discerning questions and on taking the initial steps to answer critical questions, including:

- What is the best uterine-sparing method for treatment of diffuse adenomyosis?

- Are radiofrequency or microwave ablation procedures the future of adenomyosis care?

- How do we counsel patients about fertility potential following procedural treatments?

- Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2023.01.006

- Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

- Abrao MS, Andres MP, Gingold JA, et al. Preoperative ultrasound scoring of endometriosis by AAGL 2021 endometriosis classification is concordant with laparoscopic surgical findings and distinguishes early from advanced stages. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:363-373. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2022.11.003

- Meyer R, Siedhoff M, Truong M, et al. Risk factors for major complications following minimally invasive surgeries for endometriosis in the United States. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:820-826. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.06.002

- Davenport S, Smith D, Green DJ. Barriers to a timely diagnosis of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:571-583. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005255

- Jiang L, Han Y, Song Z, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after uterus-sparing operative treatment for adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023:30:543-554. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.015

- Li S, Li Z, Lin M, et al. Efficacy of transabdominal ultrasoundguided percutaneous microwave ablation in the treatment of symptomatic adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:137-146. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.11.004

- Liu L, Tian H, Lin D, et al. Risk of recurrence and reintervention after uterine-sparing interventions for symptomatic adenomyosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:711-723. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005080

- Chang OH, Tewari S, Yao M, et al. Who places high value on the uterus? A cross-sectional survey study evaluating predictors for uterine preservation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:131-136. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.10.012

- Carey ET, Moore KJ, McClurg AB, et al. Racial disparities in hysterectomy route for benign disease: examining trends and perioperative complications from 2007 to 2018 using the NSQIP database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:627-634. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.024

- Frisch EH, Mitchell J, Yao M, et al. The impact of fertility goals on long-term quality of life in reproductive-aged women who underwent myomectomy versus hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:642-651. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.04.003 1

- Robinson WR, Mathias JG, Wood ME, et al. Ethnoracial differences in premenopausal hysterectomy: the role of symptom severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:350-359. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005225

- Harris HR, Peres LC, Johnson CE, et al. Racial differences in the association of endometriosis and uterine leiomyomas with the risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:11241138. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005191

- Atia O, Hazan E, Rotem R, et al. A scoring system developed by a machine learning algorithm to better predict adnexal torsion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:486-493. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.02.008

- Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005113

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1373-1381. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218690.24494.ce

- Scioscia M, Bruni F, Ceccaroni M, et al. Distribution of endometriotic lesions in endometriosis stage IV supports the menstrual reflux theory and requires specific preoperative assessment and therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:136-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01008.x

- Wetzel A, Philip C-A, Golfier F, et al. Surgical management of diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis: a French multicentric descriptive study. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102147. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102147

- Pagano F, Schwander A, Vaineau C, et al. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: a call for awareness and investigation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:329-334. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2023.01.006

- Casarin J, Ghezzi F, Mueller M, et al. Surgical outcomes and complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometriosis: a multicentric cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:587-592. doi:1016/j.jmig.2023.03.018

- Abrao MS, Andres MP, Gingold JA, et al. Preoperative ultrasound scoring of endometriosis by AAGL 2021 endometriosis classification is concordant with laparoscopic surgical findings and distinguishes early from advanced stages. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:363-373. doi:10.1016 /j.jmig.2022.11.003

- Meyer R, Siedhoff M, Truong M, et al. Risk factors for major complications following minimally invasive surgeries for endometriosis in the United States. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:820-826. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.06.002

- Davenport S, Smith D, Green DJ. Barriers to a timely diagnosis of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:571-583. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005255

- Jiang L, Han Y, Song Z, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after uterus-sparing operative treatment for adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023:30:543-554. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.015

- Li S, Li Z, Lin M, et al. Efficacy of transabdominal ultrasoundguided percutaneous microwave ablation in the treatment of symptomatic adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:137-146. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.11.004

- Liu L, Tian H, Lin D, et al. Risk of recurrence and reintervention after uterine-sparing interventions for symptomatic adenomyosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:711-723. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005080

- Chang OH, Tewari S, Yao M, et al. Who places high value on the uterus? A cross-sectional survey study evaluating predictors for uterine preservation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:131-136. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2022.10.012

- Carey ET, Moore KJ, McClurg AB, et al. Racial disparities in hysterectomy route for benign disease: examining trends and perioperative complications from 2007 to 2018 using the NSQIP database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:627-634. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.03.024

- Frisch EH, Mitchell J, Yao M, et al. The impact of fertility goals on long-term quality of life in reproductive-aged women who underwent myomectomy versus hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:642-651. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.04.003 1

- Robinson WR, Mathias JG, Wood ME, et al. Ethnoracial differences in premenopausal hysterectomy: the role of symptom severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:350-359. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005225

- Harris HR, Peres LC, Johnson CE, et al. Racial differences in the association of endometriosis and uterine leiomyomas with the risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:11241138. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005191

- Atia O, Hazan E, Rotem R, et al. A scoring system developed by a machine learning algorithm to better predict adnexal torsion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023;30:486-493. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2023.02.008

- Ban Y, Shen J, Wang X, et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:927-936. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005113

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1373-1381. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218690.24494.ce

- Scioscia M, Bruni F, Ceccaroni M, et al. Distribution of endometriotic lesions in endometriosis stage IV supports the menstrual reflux theory and requires specific preoperative assessment and therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:136-139. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01008.x

- Wetzel A, Philip C-A, Golfier F, et al. Surgical management of diaphragmatic and thoracic endometriosis: a French multicentric descriptive study. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102147. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102147

2021 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

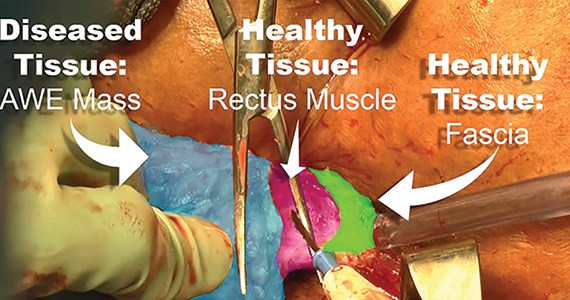

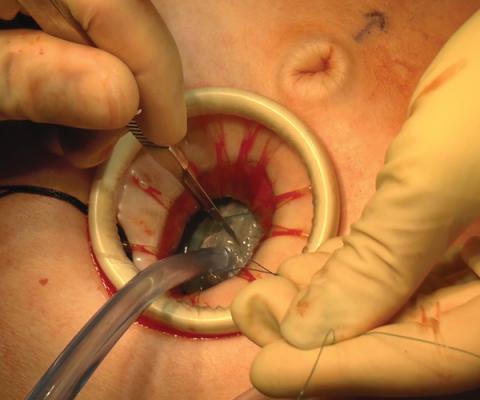

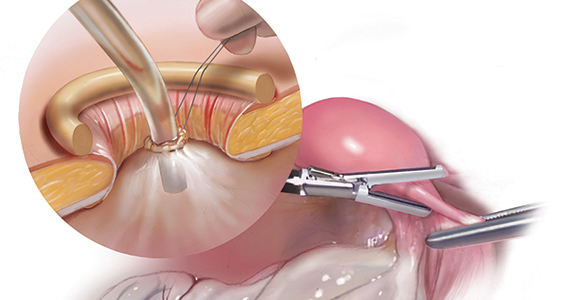

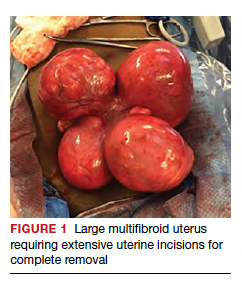

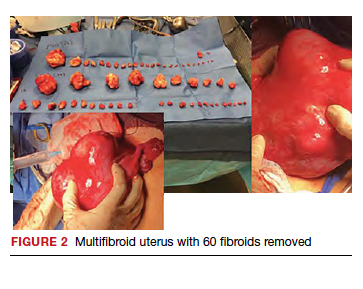

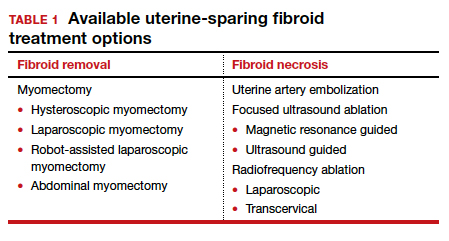

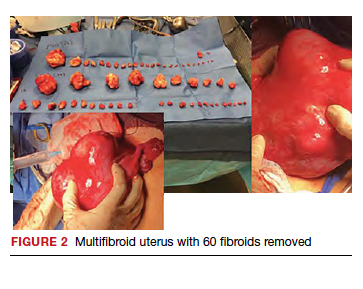

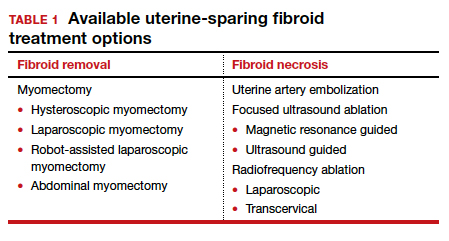

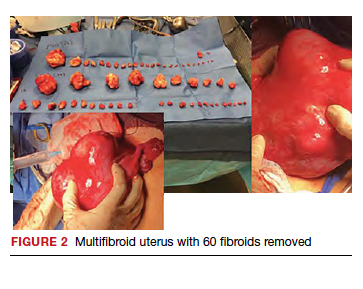

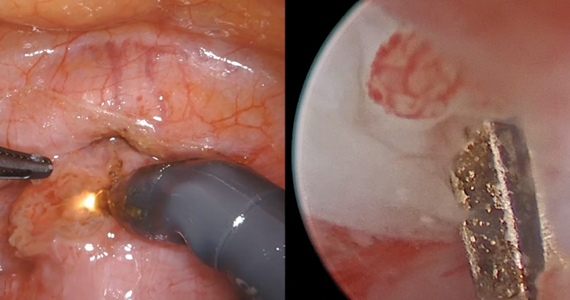

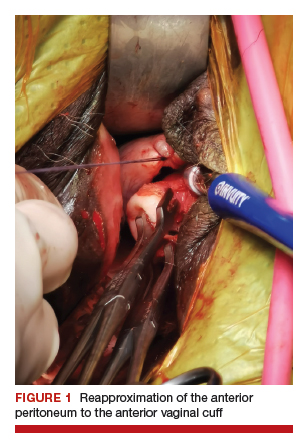

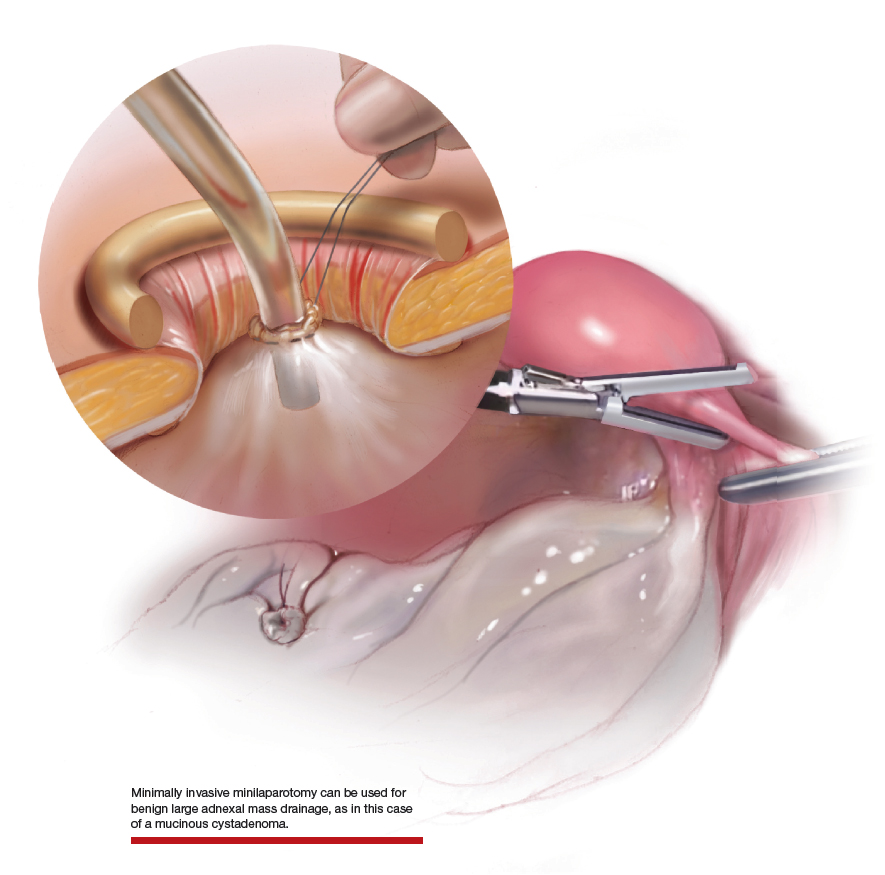

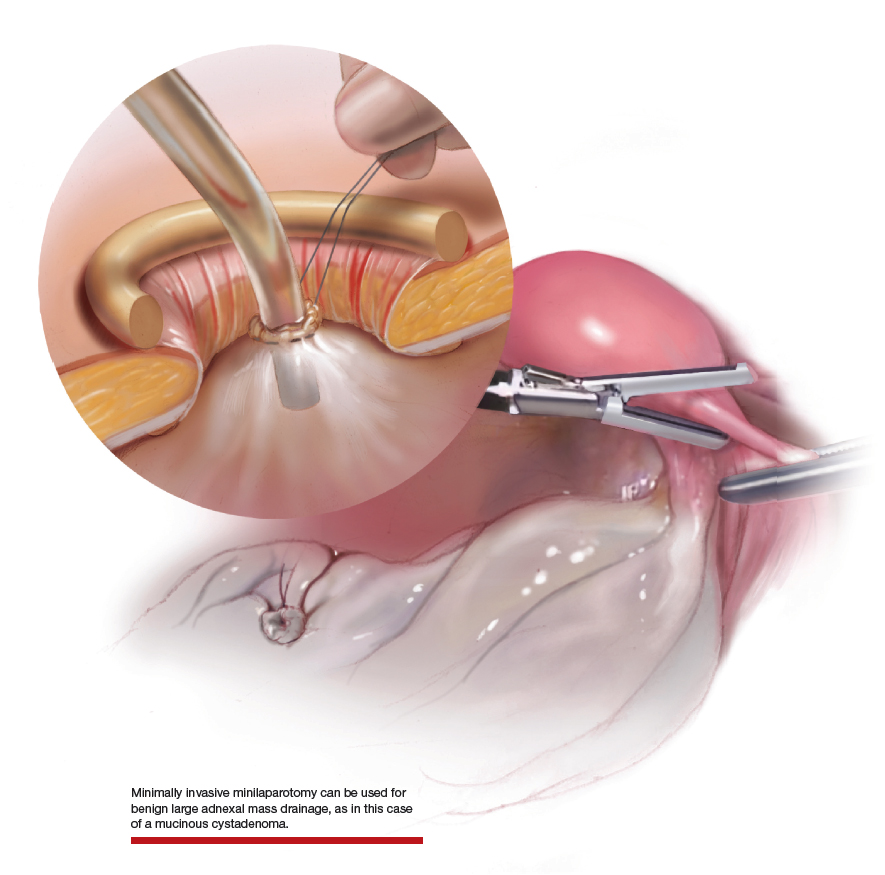

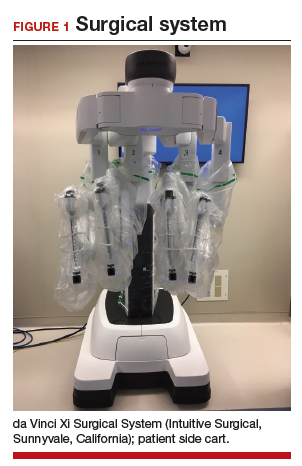

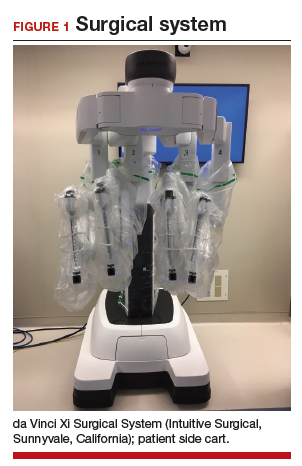

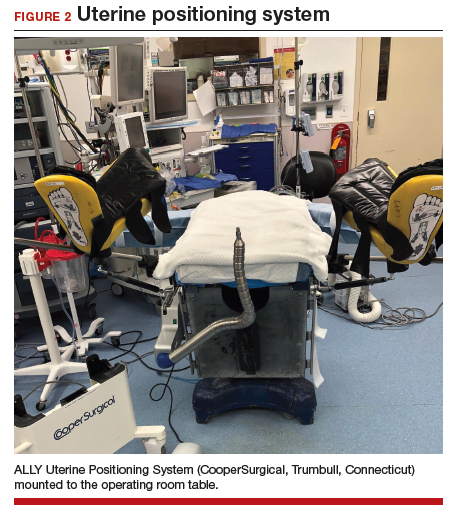

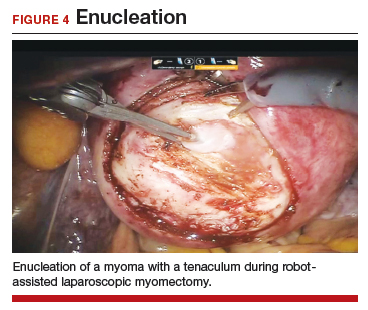

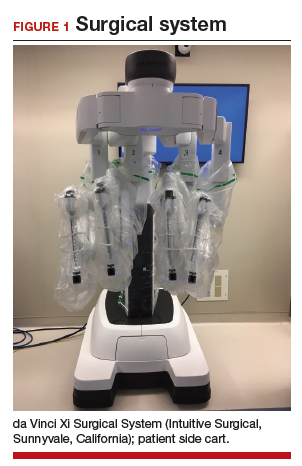

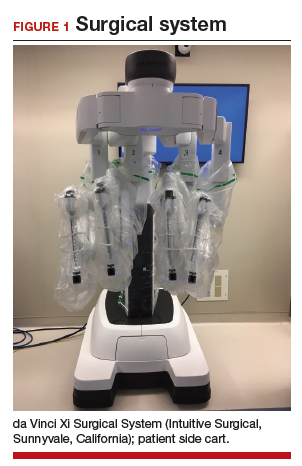

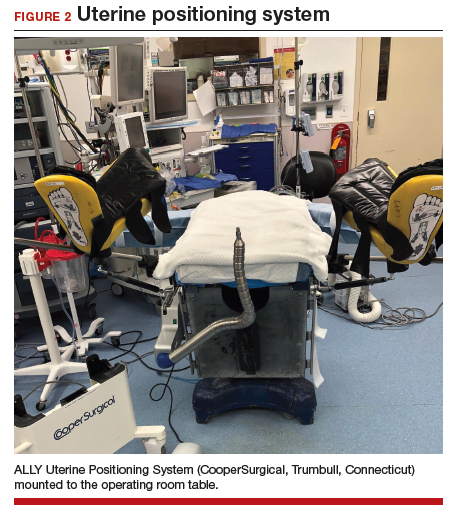

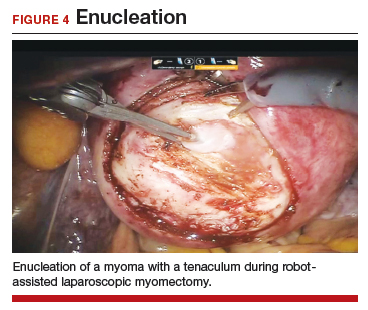

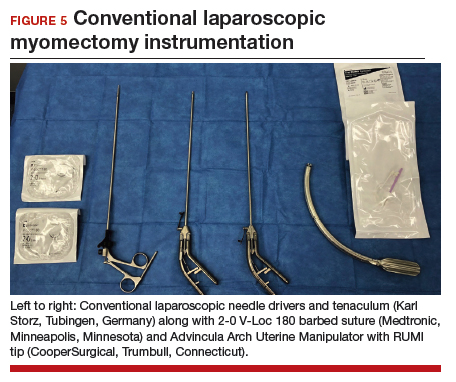

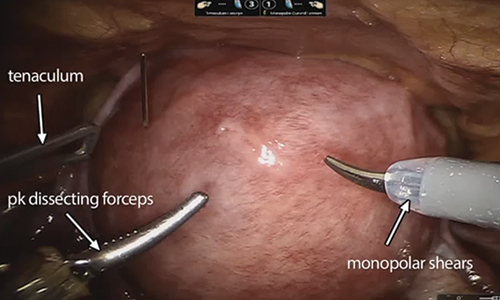

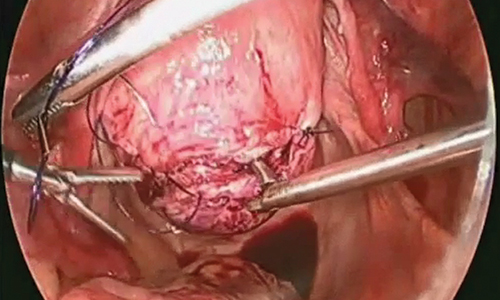

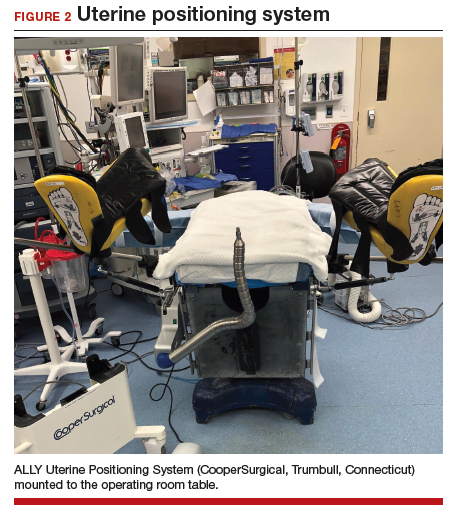

Uterine fibroids are a common condition that affects up to 80% of reproductive-age women.1 Many women with fibroids are asymptomatic, but some experience symptoms that profoundly disrupt their lives, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms including bladder and bowel dysfunction.2 Although hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic fibroids, many women seek more conservative management. Hormonal treatment, such as contraceptive pills, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, can improve heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia.3 Additionally, uterine artery embolization is a nonsurgical uterine-sparing option. However, these treatments are not ideal options for women who want to conceive.4 For reproductive-age women who desire future fertility, myomectomy has been the standard of care. Unfortunately, by the time patients become symptomatic from their fibroids and seek care, they may have numerous and/or sizable fibroids that result in high blood loss, surgical scarring, and the probable need for cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1 and 2).5

For patients who desire future conception, treatment of uterine fibroids poses a challenge in which optimizing symptomatic improvement must be balanced with protecting fertility and improving reproductive outcomes. In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (FUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have been presented as less invasive, uterine-sparing alternatives for fibroid treatment that could potentially provide that balance.

In this article, we briefly review the available uterine-sparing fibroid treatments and their outcomes and then focus specifically on RFA as a possible option to address the fibroid treatment gap for reproductive-age women who desire future fertility.

Overview of uterine-sparing treatments

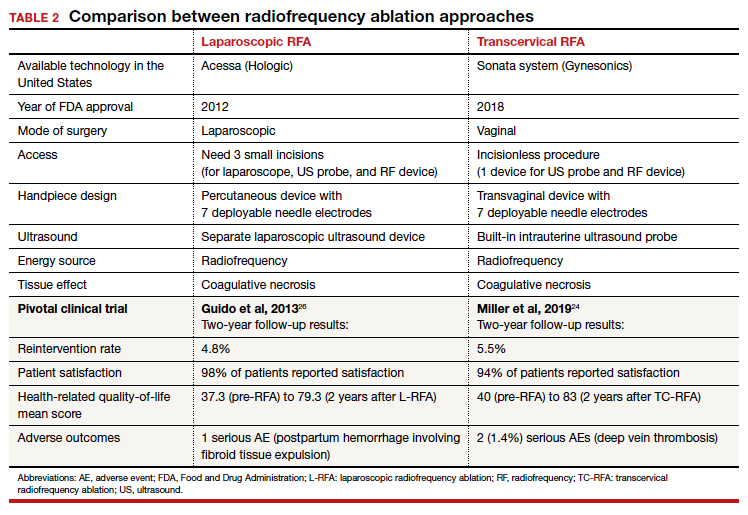

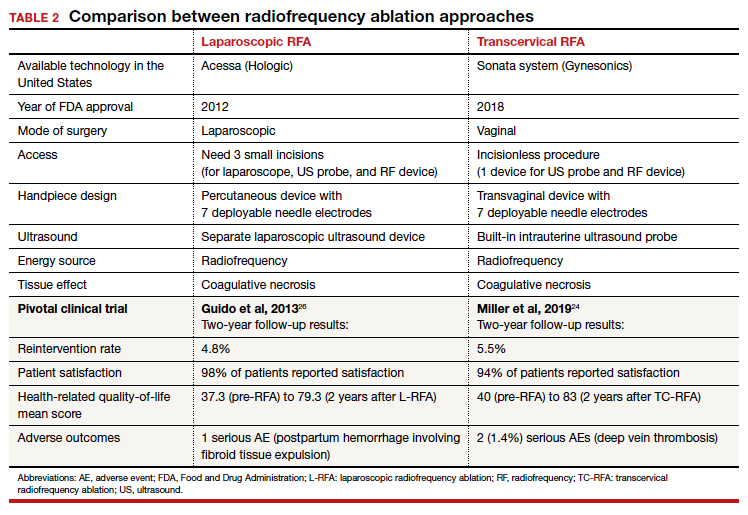

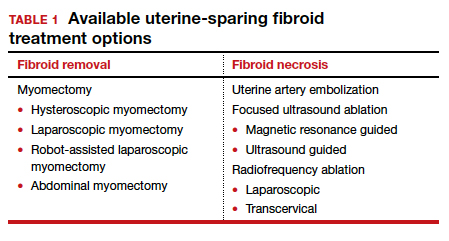

Two approaches can be pursued for conservative fibroid treatment: fibroid removal and fibroid necrosis (TABLE 1). We focus this review on outcomes for the most widely available of these treatments.

Myomectomy

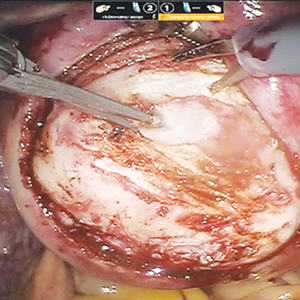

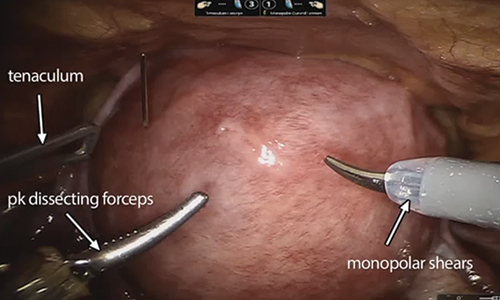

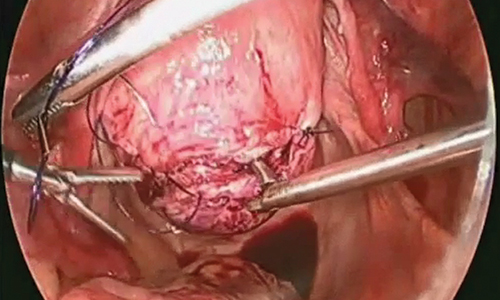

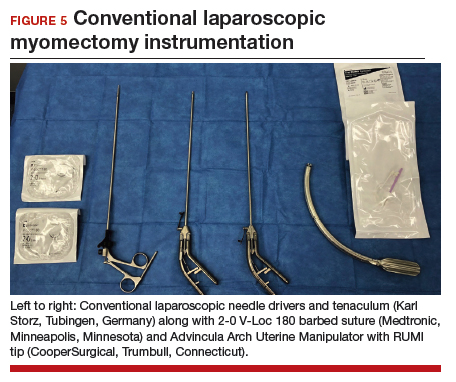

For reproductive-age women who wish to conceive, surgical removal of fibroids has been the standard of care for symptomatic patients. Myomectomy can be performed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, robot-assisted surgery, and hysteroscopy. The mode of surgery depends on the fibroid characteristics (size, number, and location) and the surgeon’s skill set. Although some variation in the data exists, overall surgical outcomes, including blood loss, postoperative pain, and length of stay, are generally more favorable for minimally invasive approaches compared with laparotomy, with no significant differences in fibroid recurrence or reproductive outcomes (live birth rate, miscarriage rate, and cesarean delivery rate).6 This comes at the expense of longer operating time compared with laparotomy.7

While improvement in abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain is reliable and usually significant after myomectomy,8 reproductive implications also warrant consideration. Myomectomy is associated with subsequent uterine adhesion formation, with some studies finding rates up to 83% to 94% depending on the surgical approach and the number of fibroids removed.9 These adhesions can impair fertility success.10 Myomectomy also is associated with high rates of cesarean delivery,5 invasive placentation (including placenta accreta spectrum),11 and uterine rupture.12 While the latter 2 complications are rare, they potentially can be catastrophic and should be kept in mind.

Continue to: Uterine artery embolization...

Uterine artery embolization

As a nonsurgical alternative to myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has gained popularity as a conservative fibroid treatment since it was introduced in 1995. It is less invasive than myomectomy, a benefit for patients who decline surgery or are not ideal candidates for surgery.13 Evidence suggests that UAE produces overall comparable symptomatic improvement compared with myomectomy. One study showed no significant differences between UAE and myomectomy in terms of decreased uterine volume and menstrual bleeding at 6-month follow-up.14 In terms of long-term outcomes, a large multicenter study showed no significant difference in reintervention rates at 7 years posttreatment between UAE and myomectomy (8.9% vs 11.2%, respectively), and a significantly higher rate of improved menstrual bleeding with UAE (79.4% vs 49.5%), with no significant difference in bulk symptoms.15 The evidence is not entirely consistent, as other studies have shown increased rates of reintervention with UAE,8,16 but overall UAE can be considered a reasonable alternative to myomectomy in terms of symptomatic improvement.

Pregnancy outcomes data, however, are mixed, and UAE often is not recommended for patients with future fertility plans. In a large review article that compared minimally invasive fibroid treatments, UAE was associated with a lower live birth rate compared with myomectomy and ablation techniques (60.6% for UAE, 75.6% for myomectomy, and 70.5% for ablation), and it also had the highest rate of miscarriage (27.4% for UAE vs 19.0% for myomectomy and 11.9% for ablation) and abnormal placentation.12 While UAE remains an effective option for conservative treatment of symptomatic fibroids, it appears to have a worse impact on reproductive outcomes compared with myomectomy or ablative treatments.

Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound

Emerging as a noninvasive ablation treatment for fibroids, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses targeted high-intensity ultrasound pulses to cause thermal and mechanical fibroid tissue disruption.17 Data on this treatment are less robust given that it is newer than myomectomy or UAE. One study showed a decrease in fibroid volume by 12% at 1 month and 15% at 6 months, with 37.1% of patients reporting marked improvement in symptoms and an additional 31.4% reporting partial improvement; these are modest numbers compared with other treatment approaches.18 Another study showed more favorable outcomes, with 74% of patients reporting clinically significant improvement in bleeding and pain, and a 12.7% reintervention rate, comparable to rates reported for UAE and myomectomy.19

Because MRgFUS is newer than UAE or myomectomy, data are limited in terms of pregnancy outcomes, particularly because initial trials excluded women with future fertility plans due to lack of knowledge regarding pregnancy safety. A follow-up case series from one of the initial studies showed a decreased miscarriage rate compared with UAE, a term delivery rate of 93%, and a similar rate of abnormal placentation.20 A more recent systematic review concluded that reproductive outcomes were noninferior to myomectomy; however, the outcomes data for MRgFUS were heterogenous and many studies did not report pregnancy rates.21

Overall, MRgFUS appears to be an effective alternative approach for symptomatic fibroids, but the long-term data are not yet conclusive and information on pregnancy safety and outcomes largely is lacking. Recent reviews have not made definitive statements on whether MRgFUS should be offered to patients desiring future fertility.

Continue to: RFA is a promising option...

RFA is a promising option

RFA is another noninvasive fibroid ablation technique that has become more widely adopted in recent years. Here, we describe the basics of RFA and its impact on fibroid symptoms and reproductive outcomes.

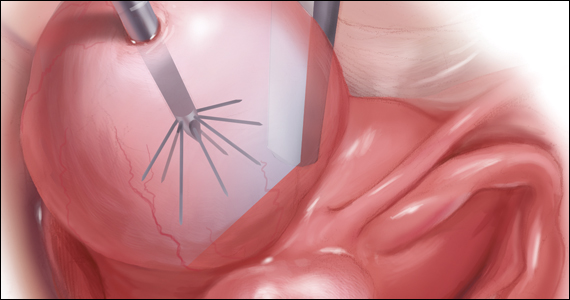

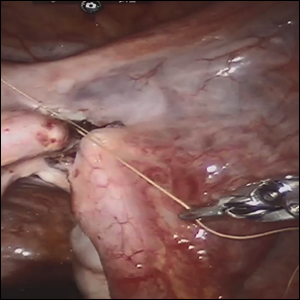

The RFA technique

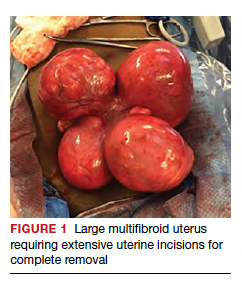

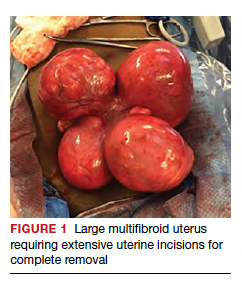

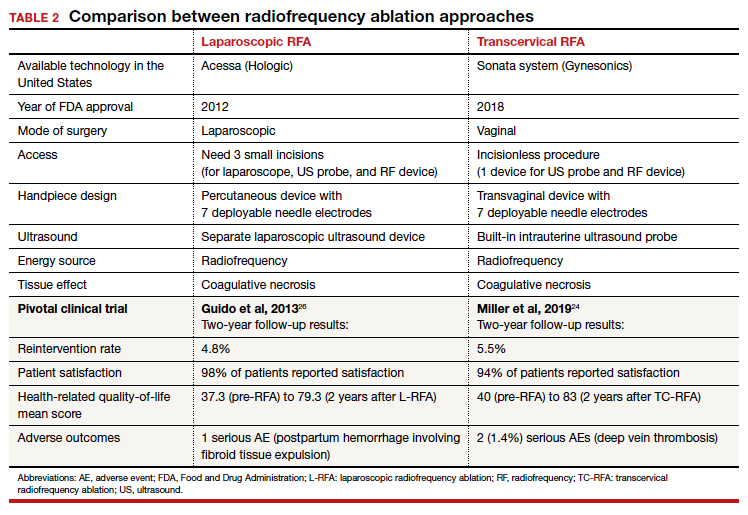

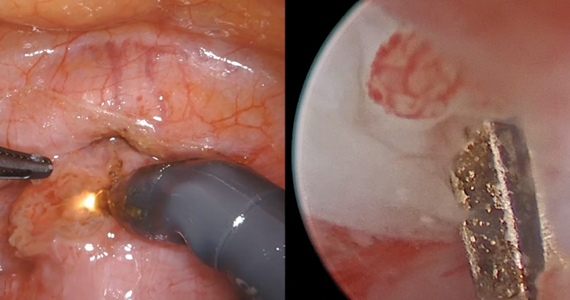

RFA uses hyperthermic energy from a handpiece and real-time ultrasound for targeted coagulative necrosis via a laparoscopic (L-RFA) or transcervical (TC-RFA) approach.22 A comparison between the 2 devices available on the market in the United States is shown in TABLE 2. Ultrasound guidance allows placement of radiofrequency needles directly into the fibroid to target local treatment to the fibroid tissue only. Once the fibroid undergoes coagulative necrosis, the process of fibroid resorption and volume reduction occurs over weeks to months, depending on the fibroid size.

Impact on fibroid symptoms

Both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA approaches have shown significant decreases in pelvic pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids and a low reintervention rate that emphasizes the durability of their impact.

A feasibility and safety study of a TC-RFA device prior to the primary clinical trials found only a 4.3% reintervention rate in the first 18 months postprocedure.23 The pivotal clinical trial of a TC-RFA device that followed also reported a low 5.5% reintervention rate in the first 24 months postprocedure, with significant improvement in health-related quality-of-life and high patient satisfaction24 (results shown in TABLE 2, along with trial results for an L-RFA device). A subsequent study of TC-RFA reported that symptomatic improvement persisted at 3-year follow-up, with a 9.2% reintervention rate comparable to existing fibroid treatments such as myomectomy and UAE.25 The original L-RFA trial also has shown similar positive results at 2-year follow-up, with a low reintervention rate of 4.8% after treatment, and similar patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvements as TC-RFA.26 While long-term data are limited by only recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a TC-RFA device in 2018, one study followed clinical trial patients for a mean duration of 64 months. This study found no surgical reinterventions in the first 3.5 years posttreatment and a persistent reduction in fibroid symptoms from baseline 64.9 points to 27.6 points, as assessed by a validated symptom severity scale (out of 100 points).27 Similar improvements in health-related quality-of life-were also found to persist for years posttreatment.4

In a large systematic review that compared L-RFA, MRgFUS, UAE, and myomectomy, L-RFA had similar improvement rates in quality-of-life and symptom severity scores compared with myomectomy, with no significant difference in reintervention rates.28 This review also noted minimal heterogeneity among RFA meta-analyses data in contrast to significant heterogeneity among UAE and myomectomy data.

Reproductive outcomes

Similar to MRgFUS, the initial studies of RFA devices largely excluded women with future fertility plans, as data on safety were lacking. However, many RFA devices are now on the market across the globe, and subsequent pregnancies have been tracked and reported.

A large case series that included clinical trials and commercial settings reported a miscarriage rate (13.3%) similar to that of the general obstetric population and no cases of uterine rupture, invasive placentation, preterm delivery, or placental abruption.29 Other case series have reported live birth rates similar those with myomectomy, and safe and favorable pregnancy outcomes with RFA have been supported by larger systematic reviews of all ablation techniques.12

Continue to: Uterine impact...

Uterine impact

One study of TC-RFA patients showed a greater than 65% reduction in fibroid volume (with a 90% reduction in fibroid volume for fibroids larger than 6 cm prior to RFA), and 54% of patients reported complete resolution of symptoms, with another 36% reporting decreased symptoms.30 Similar decreases in fibroid volume, ranging from 65% to 84%, have been reported in numerous follow-up studies, with significant decreases in bleeding and pain in 78% to 88% of patients.23,31-33 Additionally, a large secondary analysis of a TC-RFA clinical trial showed that patients did not have any significant decrease in uterine wall thickness or integrity on follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging compared with baseline measurements, and they did not have any new myometrial scars (assessed as nonperfused linear areas).22

As with other ablation techniques, most data on RFA pregnancy outcomes come from case series, and further research and evaluation are needed. Existing studies, however, have demonstrated promising aspects of RFA that argue its usefulness in women with fertility plans.

A prospective trial that evaluated intrauterine adhesion formation with use of a TC-RFA device found no new adhesions on 6-week follow-up hysteroscopy compared with baseline pre-RFA hysteroscopy.34 Because intrauterine adhesion formation and uterine rupture are both significant concerns with other uterine-sparing fibroid treatment approaches such as myomectomy, these findings suggest that RFA may be a better alternative for women who are planning future pregnancies, as they may have increased fertility success and decreased catastrophic complications.

The consensus is growing that RFA is a safe and effective option for women who desire minimally invasive fibroid treatment and want to preserve fertility.

Unique benefits of RFA

In this article, we highlight RFA as an emerging treatment option for fibroid management, particularly for women who desire a uterine-sparing approach to preserve their reproductive options. Although myomectomy has been the standard of care for many years, with UAE as the alternative nonsurgical treatment, neither approach provides the best balance between symptomatic improvement and reproductive outcomes, and neither is without pregnancy risks. In addition, many women with symptomatic fibroids do not desire future conception but decline fibroid removal for religious or personal reasons. RFA offers these women an alternative minimally invasive option for uterine-sparing fibroid treatment.

RFA presents a unique “incision-free” fibroid treatment that is truly minimally invasive. This technique minimizes the risks associated with myomectomy, such as intra-abdominal adhesions, intrauterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome), need for cesarean delivery, and pregnancy complications such as uterine rupture or invasive placentation. Furthermore, the evolution of an RFA transcervical approach has enabled treatment with no abdominal or uterine incisions, thus offering all the above reproductive benefits as well as the operative benefits of a faster recovery, less pain, and less risk of intraperitoneal surgical complications.

While many women desire uterine-sparing fibroid treatment even without future fertility plans, the larger question is whether we should treat fibroids more strategically for women who desire future fertility. Myomectomy and UAE are effective and reliable in terms of fibroid symptomatic improvement, but RFA promises more beneficial reproductive outcomes. The ability to avoid uterine myometrial incisions and still attain significant symptomatic improvement should be prioritized in these patients.

Currently, RFA is not approved by the FDA as a fertility-enabling treatment, and these patients have been largely excluded from RFA studies. However, the reproductive-age patient who desires future conception may benefit most from RFA. Furthermore, RFA technology also could address the gap in uterine-sparing treatment for reproductive-age women with adenomyosis. Although a complete review of adenomyosis treatment is beyond the scope of this article, recent studies show that RFA produces similar improvement in both uterine volume and symptom severity in women with adenomyosis.35-37 ●

The RFA data suggest that both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA offer a safe and effective alternative treatment option for patients with symptomatic fibroids who seek uterine-sparing treatment, and transcervical RFA offers the least invasive treatment option. Women with fibroids who wish to conceive currently face a challenging treatment gap in clinical medicine, and future research is needed to address this concern in these patients. RFA is promising and appears to be a better fertility-enabling conservative fibroid treatment than the current options of myomectomy or UAE.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1646-1655.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005073.

- Paul GP, Naik SA, Madhu KN, et al. Complications of laparoscopic myomectomy: a single surgeon’s series of 1001 cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:385-390.

- Flyckt R, Coyne K, Falcone T. Minimally invasive myomectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:252-272.

- Bean EM, Cutner A, Holland T, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy: a single-center retrospective review of 514 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:485-493.

- Broder MS, Goodwin S, Chen G, et al. Comparison of longterm outcomes of myomectomy and uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):864-868.

- Torng PL. Adhesion prevention in laparoscopic myomectomy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:7-11.

- Herrmann A, Torres-de la Roche LA, Krentel H, et al. Adhesions after laparoscopic myomectomy: incidence, risk factors, complications, and prevention. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:190-197.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:99-108.

- Khaw SC, Anderson RA, Lui MW. Systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after fertility-preserving treatment of uterine fibroids. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;40:429-444.

- Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, et al. Uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:29-34.

- Goodwin SC, Bradley LD, Lipman JC, et al. Uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:14-21

- Jia JB, Nguyen ET, Ravilla A, et al. Comparison of uterine artery embolization and myomectomy: a long-term analysis of 863 patients. Am J Interv Radiol. 2020;5:1.

- Huang JY, Kafy S, Dugas A, et al. Failure of uterine fibroid embolization. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:30-35.

- Hesley GK, Gorny KR, Woodrum DA. MR-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:5-13.

- Rabinovici J, Inbar Y, Revel A, et al. Clinical improvement and shrinkage of uterine fibroids after thermal ablation by magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:771-777.

- Mindjuk I, Trumm CG, Herzog P, et al. MRI predictors of clinical success in MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) treatments of uterine fibroids: results from a single centre. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1317-1328.

- Rabinovici J, David M, Fukunishi H, et al; MRgFUS Study Group. Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:199-209.

- Anneveldt KJ, Oever HJV, Nijholt IM, et al. Systematic review of reproductive outcomes after high intensity focused ultrasound treatment of uterine fibroids. Eur J Radiol. 2021;141:109801.

- Bongers M, Gupta J, Garza-Leal JG, et al. The INTEGRITY trial: preservation of uterine-wall integrity 12 months after transcervical fibroid ablation with the Sonata system. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:299-303.

- Kim CH, Kim SR, Lee HA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided radiofrequency myolysis for uterine myomas. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:559–563.

- Miller CE, Osman KM. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic uterine fibroids: 2-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:345-349.

- Lukes A, Green MA. Three-year results of the Sonata pivotal trial of transcervical fibroid ablation for symptomatic uterine myomata. J Gynecol Surg. 2020;36:228-233.

- Guido RS, Macer JA, Abbott K, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of fibroids: a prospective, clinical analysis of two years’ outcome from the Halt trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:139.

- Garza-Leal JG. Long-term clinical outcomes of transcervical radiofrequency ablation of uterine fibroids: the VITALITY study. J Gynecol Surg. 2019;35:19-23.

- Cope AG, Young RJ, Stewart EA. Non-extirpative treatments for uterine myomas: measuring success. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:442-452.e4.

- Berman JM, Shashoua A, Olson C, et al. Case series of reproductive outcomes after laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:639-645.

- Jones S, O’Donovan P, Toub D. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:194839.

- Bergamini V, Ghezzi F, Cromi A, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation: a new approach to symptomatic uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:768-773.

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, et al. Midterm outcome of radiofrequency thermal ablation for symptomatic uterine myomas. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2081-2085.

- Szydłowska I, Starczewski A. Laparoscopic coagulation of uterine myomas with the use of a unipolar electrode. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:99-103.

- Bongers M, Quinn SD, Mueller MD et al. Evaluation of uterine patency following transcervical uterine fibroid ablation with the Sonata system (the OPEN clinical trial). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;242:122-125.

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, et al. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:201601132.

- Polin M, Krenitsky N, Hur HC. Transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic adenomyosis: a case report. J Minim Invasive Gyn. 2021;28:S152-S153.

- Scarperi S, Pontrelli G, Campana C, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation for uterine adenomyosis. JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00071.

Uterine fibroids are a common condition that affects up to 80% of reproductive-age women.1 Many women with fibroids are asymptomatic, but some experience symptoms that profoundly disrupt their lives, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, and bulk symptoms including bladder and bowel dysfunction.2 Although hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment for symptomatic fibroids, many women seek more conservative management. Hormonal treatment, such as contraceptive pills, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, can improve heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia.3 Additionally, uterine artery embolization is a nonsurgical uterine-sparing option. However, these treatments are not ideal options for women who want to conceive.4 For reproductive-age women who desire future fertility, myomectomy has been the standard of care. Unfortunately, by the time patients become symptomatic from their fibroids and seek care, they may have numerous and/or sizable fibroids that result in high blood loss, surgical scarring, and the probable need for cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1 and 2).5

For patients who desire future conception, treatment of uterine fibroids poses a challenge in which optimizing symptomatic improvement must be balanced with protecting fertility and improving reproductive outcomes. In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (FUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have been presented as less invasive, uterine-sparing alternatives for fibroid treatment that could potentially provide that balance.

In this article, we briefly review the available uterine-sparing fibroid treatments and their outcomes and then focus specifically on RFA as a possible option to address the fibroid treatment gap for reproductive-age women who desire future fertility.

Overview of uterine-sparing treatments

Two approaches can be pursued for conservative fibroid treatment: fibroid removal and fibroid necrosis (TABLE 1). We focus this review on outcomes for the most widely available of these treatments.

Myomectomy

For reproductive-age women who wish to conceive, surgical removal of fibroids has been the standard of care for symptomatic patients. Myomectomy can be performed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, robot-assisted surgery, and hysteroscopy. The mode of surgery depends on the fibroid characteristics (size, number, and location) and the surgeon’s skill set. Although some variation in the data exists, overall surgical outcomes, including blood loss, postoperative pain, and length of stay, are generally more favorable for minimally invasive approaches compared with laparotomy, with no significant differences in fibroid recurrence or reproductive outcomes (live birth rate, miscarriage rate, and cesarean delivery rate).6 This comes at the expense of longer operating time compared with laparotomy.7

While improvement in abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain is reliable and usually significant after myomectomy,8 reproductive implications also warrant consideration. Myomectomy is associated with subsequent uterine adhesion formation, with some studies finding rates up to 83% to 94% depending on the surgical approach and the number of fibroids removed.9 These adhesions can impair fertility success.10 Myomectomy also is associated with high rates of cesarean delivery,5 invasive placentation (including placenta accreta spectrum),11 and uterine rupture.12 While the latter 2 complications are rare, they potentially can be catastrophic and should be kept in mind.

Continue to: Uterine artery embolization...

Uterine artery embolization

As a nonsurgical alternative to myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has gained popularity as a conservative fibroid treatment since it was introduced in 1995. It is less invasive than myomectomy, a benefit for patients who decline surgery or are not ideal candidates for surgery.13 Evidence suggests that UAE produces overall comparable symptomatic improvement compared with myomectomy. One study showed no significant differences between UAE and myomectomy in terms of decreased uterine volume and menstrual bleeding at 6-month follow-up.14 In terms of long-term outcomes, a large multicenter study showed no significant difference in reintervention rates at 7 years posttreatment between UAE and myomectomy (8.9% vs 11.2%, respectively), and a significantly higher rate of improved menstrual bleeding with UAE (79.4% vs 49.5%), with no significant difference in bulk symptoms.15 The evidence is not entirely consistent, as other studies have shown increased rates of reintervention with UAE,8,16 but overall UAE can be considered a reasonable alternative to myomectomy in terms of symptomatic improvement.

Pregnancy outcomes data, however, are mixed, and UAE often is not recommended for patients with future fertility plans. In a large review article that compared minimally invasive fibroid treatments, UAE was associated with a lower live birth rate compared with myomectomy and ablation techniques (60.6% for UAE, 75.6% for myomectomy, and 70.5% for ablation), and it also had the highest rate of miscarriage (27.4% for UAE vs 19.0% for myomectomy and 11.9% for ablation) and abnormal placentation.12 While UAE remains an effective option for conservative treatment of symptomatic fibroids, it appears to have a worse impact on reproductive outcomes compared with myomectomy or ablative treatments.

Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound

Emerging as a noninvasive ablation treatment for fibroids, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses targeted high-intensity ultrasound pulses to cause thermal and mechanical fibroid tissue disruption.17 Data on this treatment are less robust given that it is newer than myomectomy or UAE. One study showed a decrease in fibroid volume by 12% at 1 month and 15% at 6 months, with 37.1% of patients reporting marked improvement in symptoms and an additional 31.4% reporting partial improvement; these are modest numbers compared with other treatment approaches.18 Another study showed more favorable outcomes, with 74% of patients reporting clinically significant improvement in bleeding and pain, and a 12.7% reintervention rate, comparable to rates reported for UAE and myomectomy.19

Because MRgFUS is newer than UAE or myomectomy, data are limited in terms of pregnancy outcomes, particularly because initial trials excluded women with future fertility plans due to lack of knowledge regarding pregnancy safety. A follow-up case series from one of the initial studies showed a decreased miscarriage rate compared with UAE, a term delivery rate of 93%, and a similar rate of abnormal placentation.20 A more recent systematic review concluded that reproductive outcomes were noninferior to myomectomy; however, the outcomes data for MRgFUS were heterogenous and many studies did not report pregnancy rates.21

Overall, MRgFUS appears to be an effective alternative approach for symptomatic fibroids, but the long-term data are not yet conclusive and information on pregnancy safety and outcomes largely is lacking. Recent reviews have not made definitive statements on whether MRgFUS should be offered to patients desiring future fertility.

Continue to: RFA is a promising option...

RFA is a promising option

RFA is another noninvasive fibroid ablation technique that has become more widely adopted in recent years. Here, we describe the basics of RFA and its impact on fibroid symptoms and reproductive outcomes.

The RFA technique

RFA uses hyperthermic energy from a handpiece and real-time ultrasound for targeted coagulative necrosis via a laparoscopic (L-RFA) or transcervical (TC-RFA) approach.22 A comparison between the 2 devices available on the market in the United States is shown in TABLE 2. Ultrasound guidance allows placement of radiofrequency needles directly into the fibroid to target local treatment to the fibroid tissue only. Once the fibroid undergoes coagulative necrosis, the process of fibroid resorption and volume reduction occurs over weeks to months, depending on the fibroid size.

Impact on fibroid symptoms

Both laparoscopic and transcervical RFA approaches have shown significant decreases in pelvic pain and heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids and a low reintervention rate that emphasizes the durability of their impact.