User login

Few Women Know Uterine Fibroid Risk, Treatment Options

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

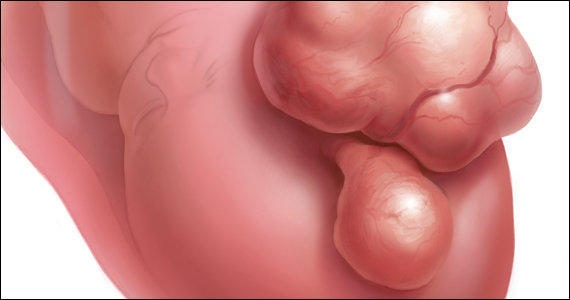

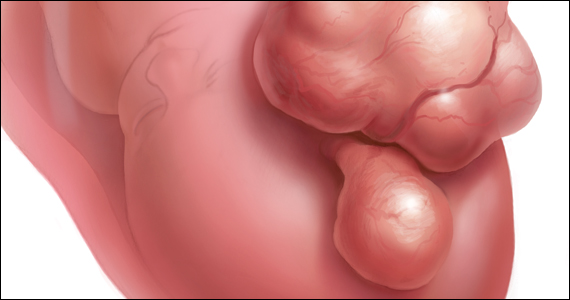

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Most women (72%) are not aware they are at risk for developing uterine fibroids, though up to 77% of women will develop them in their lifetime, results of a new survey indicate.

Data from The Harris Poll, conducted on behalf of the Society of Interventional Radiology, also found that 17% of women mistakenly think a hysterectomy is the only treatment option, including more than one in four women (27%) who are between the ages of 18 and 34. Results were shared in a press release. The survey included 1,122 US women, some who have been diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Fibroids may not cause symptoms for some, but some women may have heavy, prolonged, debilitating bleeding. Some women experience pelvic pain, a diminished sex life, and declining energy. However, the growths do not spread to other body regions and typically are not dangerous.

Hysterectomy Is Only One Option

Among the women in the survey who had been diagnosed with fibroids, 53% were presented the option of hysterectomy and 20% were told about other, less-invasive options, including over-the-counter NSAIDs (19%); uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) (17%); oral contraceptives (17%); and endometrial ablation (17%).

“Women need to be informed about the complete range of options available for treating their uterine fibroids, not just the surgical options as is most commonly done by gynecologists,” John C. Lipman, MD, founder and medical director of the Atlanta Fibroid Center in Smyrna, Georgia, said in the press release.

The survey also found that:

- More than half of women ages 18-34 (56%) and women ages 35-44 (51%) were either not familiar with uterine fibroids or never heard of them.

- Awareness was particularly low among Hispanic women, as 50% of Hispanic women say they’ve never heard of or aren’t familiar with the condition, compared with 37% of Black women who answered that way.

- More than one third (36%) of Black women and 22% of Hispanic women mistakenly think they are not at risk for developing fibroids, yet research has shown that uterine fibroids are three times more common in Black women and two times more common in Hispanic women than in White women.

For this study, the full sample data is accurate to within +/– 3.2 percentage points using a 95% confidence level. The data are part of the report “The Fibroid Fix: What Women Need to Know,” published on July 9 by the Society of Interventional Radiology.

Linda Fan, MD, chief of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, said she is not surprised by those numbers. She says many patients are referred to her department who have not been given the full array of medical options for their fibroids or have not had thorough discussions with their providers, such as whether they want to preserve their fertility, or how they feel about an incision, undergoing anesthesia, or having their uterus removed.

Sometimes the hysterectomy choice is clear, she said — for instance, if there are indications of the rare cancer leiomyosarcoma, or if a postmenopausal woman has rapid growth of fibroids or heavy bleeding. Fibroids should not start growing after menopause, she said.

Additional options include radiofrequency ablation, performed while a patient is under anesthesia, by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. The procedure uses ultrasound to watch a probe as it shrinks the fibroids with heat.

Currently, if a woman wants large fibroids removed and wants to keep her fertility options open, Dr. Fan says, myomectomy or medication are best “because we have the most information or data on (those options).”

When treating patients who don’t prioritize fertility, she said, UFE is a good option that doesn’t need incisions or anesthesia. But patients sometimes require a lot of pain medication afterward, Dr. Fan said. With radiofrequency ablation, specifically the Acessa and Sonata procedures, she said, “patients don’t experience a lot of pain after the procedure because the shrinking happens when they’re asleep under anesthesia.”

Uterine Fibroid Embolization a Nonsurgical Option

The report describes how UFE works but the Harris Poll showed that 60% of women who have heard of UFE did not hear about it first from a healthcare provider.

“UFE is a nonsurgical treatment, performed by interventional radiologists, that has been proven to significantly reduce heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve uterine pain, and improve energy levels,” the authors write. “Through a tiny incision in the wrist or thigh, a catheter is guided via imaging to the vessels leading to the fibroids. Through this catheter, small clear particles are injected to block the blood flow leading to the fibroids causing them to shrink and disappear.”

After UFE, most women leave the hospital the day of or the day after treatment, according to the report authors, who add that many patients also report they can resume normal activity in about 2 weeks, more quickly than with surgical treatments.

In some cases, watchful waiting will be the best option, the report notes, and that may require repeated checkups and scans.

Dr. Lipman is an adviser on The Fibroid Fix report.

Myomectomy best for avoiding reintervention after fibroid procedures

Reintervention rates after uterus-preserving surgery for leiomyomata were lowest after vaginal myomectomy, the most frequent among four therapeutic approaches, a large cohort study reported.

Accounting for censoring, the 7-year reintervention risk for vaginal myomectomy was 20.6%, followed by uterine artery embolization (26%), endometrial ablation (35.5%), and hysteroscopic myomectomy (37%).

Hysterectomies accounted for 63.2% of reinterventions according to lead author Susanna D. Mitro, PhD, a research scientist in the Division of Research and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and colleagues.

Risk did not vary by body mass index, race/ethnicity, or Neighborhood Deprivation Index, but did vary for some procedures by age and parity,

These findings generally align with earlier research and “illustrate clinically meaningful long-term differences in reintervention rates after a first uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Study

In a cohort of 10,324 patients ages 18-50, 19.9% were Asian, 21.2% Black, 21.3% Hispanic, and 32.5% White, with 5.2% of other races and ethnicities. The most affected age groups were 41-45 and 46-50 years. All participants underwent a first uterus-preserving procedure after leiomyoma diagnosis according to 2009-2021 electronic health records at Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Reintervention referred to a second uterus-preserving procedure or hysterectomy. Median follow-up was 3.8 years (interquartile range, 1.8-7.4 years), and the proportions of index procedures were as follows: 18% (1857) for hysteroscopic myomectomy; 16.2% (1669) for uterine artery embolization; 21.4% (2211) for endometrial ablations; and 44.4% (4,587) for myomectomy.

Reintervention rates were higher in younger patients after uterine artery embolization, with patients ages 18-35 at the index procedure having 1.4-3.7 times greater reintervention rates than patients ages 46-50 years. Reintervention rates for hysteroscopic myomectomy varied by parity, with multiparous patients at 35% greater risk than their nulliparous counterparts.

On the age issue, the authors note that symptom recurrence may be less common in older patients, perhaps because of the onset of menopause. “Alternatively, findings may be explained by age-specific care strategies: Older patients experiencing symptom recurrence may prefer to wait until the onset of menopause rather than pursuing another surgical treatment,” they wrote.

A recent study with 7 years’ follow-up reported a 2.4 times greater risk of hysterectomy after uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy. Reintervention rates may be lower after myomectomy because otherwise asymptomatic patients pursue myomectomy to treat infertility, the authors wrote. Alternatively, myomectomy may more completely remove leiomyomas.

These common benign tumors take a toll on healthcare resources, in 2012 costing up to $9.4 billion annually (in 2010 dollars) for related surgeries, medications, and procedures. Leiomyomas are reportedly the most frequent reason for hysterectomy.

Robust data on the optimal therapeutic approach to fibroids have been sparse, however, with a 2017 comparative-effectiveness review from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reporting that evidence on leiomyoma treatments was insufficient to guide clinical care. Few well-conducted trials of leiomyoma treatment have directly compared different treatment options, the authors noted.

The rate of myomectomy is reported to be 9.2 per 10,000 woman-years in Black women and 1.3 per 10,000 woman years in White women, and the recurrence rate after myomectomy can be as great as 60% when patients are followed up to 5 years.

The authors said their findings “may be a reference to discuss expectations for treatment outcomes when choosing initial uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas, especially for patients receiving treatment years before the likely onset of menopause.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Wise is a paid consultant for AbbVie and has received in-kind donations from Swiss Precision Diagnostics and Kindara.com; she has also received payment from the Gates Foundation.

Reintervention rates after uterus-preserving surgery for leiomyomata were lowest after vaginal myomectomy, the most frequent among four therapeutic approaches, a large cohort study reported.

Accounting for censoring, the 7-year reintervention risk for vaginal myomectomy was 20.6%, followed by uterine artery embolization (26%), endometrial ablation (35.5%), and hysteroscopic myomectomy (37%).

Hysterectomies accounted for 63.2% of reinterventions according to lead author Susanna D. Mitro, PhD, a research scientist in the Division of Research and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and colleagues.

Risk did not vary by body mass index, race/ethnicity, or Neighborhood Deprivation Index, but did vary for some procedures by age and parity,

These findings generally align with earlier research and “illustrate clinically meaningful long-term differences in reintervention rates after a first uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Study

In a cohort of 10,324 patients ages 18-50, 19.9% were Asian, 21.2% Black, 21.3% Hispanic, and 32.5% White, with 5.2% of other races and ethnicities. The most affected age groups were 41-45 and 46-50 years. All participants underwent a first uterus-preserving procedure after leiomyoma diagnosis according to 2009-2021 electronic health records at Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Reintervention referred to a second uterus-preserving procedure or hysterectomy. Median follow-up was 3.8 years (interquartile range, 1.8-7.4 years), and the proportions of index procedures were as follows: 18% (1857) for hysteroscopic myomectomy; 16.2% (1669) for uterine artery embolization; 21.4% (2211) for endometrial ablations; and 44.4% (4,587) for myomectomy.

Reintervention rates were higher in younger patients after uterine artery embolization, with patients ages 18-35 at the index procedure having 1.4-3.7 times greater reintervention rates than patients ages 46-50 years. Reintervention rates for hysteroscopic myomectomy varied by parity, with multiparous patients at 35% greater risk than their nulliparous counterparts.

On the age issue, the authors note that symptom recurrence may be less common in older patients, perhaps because of the onset of menopause. “Alternatively, findings may be explained by age-specific care strategies: Older patients experiencing symptom recurrence may prefer to wait until the onset of menopause rather than pursuing another surgical treatment,” they wrote.

A recent study with 7 years’ follow-up reported a 2.4 times greater risk of hysterectomy after uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy. Reintervention rates may be lower after myomectomy because otherwise asymptomatic patients pursue myomectomy to treat infertility, the authors wrote. Alternatively, myomectomy may more completely remove leiomyomas.

These common benign tumors take a toll on healthcare resources, in 2012 costing up to $9.4 billion annually (in 2010 dollars) for related surgeries, medications, and procedures. Leiomyomas are reportedly the most frequent reason for hysterectomy.

Robust data on the optimal therapeutic approach to fibroids have been sparse, however, with a 2017 comparative-effectiveness review from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reporting that evidence on leiomyoma treatments was insufficient to guide clinical care. Few well-conducted trials of leiomyoma treatment have directly compared different treatment options, the authors noted.

The rate of myomectomy is reported to be 9.2 per 10,000 woman-years in Black women and 1.3 per 10,000 woman years in White women, and the recurrence rate after myomectomy can be as great as 60% when patients are followed up to 5 years.

The authors said their findings “may be a reference to discuss expectations for treatment outcomes when choosing initial uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas, especially for patients receiving treatment years before the likely onset of menopause.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Wise is a paid consultant for AbbVie and has received in-kind donations from Swiss Precision Diagnostics and Kindara.com; she has also received payment from the Gates Foundation.

Reintervention rates after uterus-preserving surgery for leiomyomata were lowest after vaginal myomectomy, the most frequent among four therapeutic approaches, a large cohort study reported.

Accounting for censoring, the 7-year reintervention risk for vaginal myomectomy was 20.6%, followed by uterine artery embolization (26%), endometrial ablation (35.5%), and hysteroscopic myomectomy (37%).

Hysterectomies accounted for 63.2% of reinterventions according to lead author Susanna D. Mitro, PhD, a research scientist in the Division of Research and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and colleagues.

Risk did not vary by body mass index, race/ethnicity, or Neighborhood Deprivation Index, but did vary for some procedures by age and parity,

These findings generally align with earlier research and “illustrate clinically meaningful long-term differences in reintervention rates after a first uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The Study

In a cohort of 10,324 patients ages 18-50, 19.9% were Asian, 21.2% Black, 21.3% Hispanic, and 32.5% White, with 5.2% of other races and ethnicities. The most affected age groups were 41-45 and 46-50 years. All participants underwent a first uterus-preserving procedure after leiomyoma diagnosis according to 2009-2021 electronic health records at Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Reintervention referred to a second uterus-preserving procedure or hysterectomy. Median follow-up was 3.8 years (interquartile range, 1.8-7.4 years), and the proportions of index procedures were as follows: 18% (1857) for hysteroscopic myomectomy; 16.2% (1669) for uterine artery embolization; 21.4% (2211) for endometrial ablations; and 44.4% (4,587) for myomectomy.

Reintervention rates were higher in younger patients after uterine artery embolization, with patients ages 18-35 at the index procedure having 1.4-3.7 times greater reintervention rates than patients ages 46-50 years. Reintervention rates for hysteroscopic myomectomy varied by parity, with multiparous patients at 35% greater risk than their nulliparous counterparts.

On the age issue, the authors note that symptom recurrence may be less common in older patients, perhaps because of the onset of menopause. “Alternatively, findings may be explained by age-specific care strategies: Older patients experiencing symptom recurrence may prefer to wait until the onset of menopause rather than pursuing another surgical treatment,” they wrote.

A recent study with 7 years’ follow-up reported a 2.4 times greater risk of hysterectomy after uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy. Reintervention rates may be lower after myomectomy because otherwise asymptomatic patients pursue myomectomy to treat infertility, the authors wrote. Alternatively, myomectomy may more completely remove leiomyomas.

These common benign tumors take a toll on healthcare resources, in 2012 costing up to $9.4 billion annually (in 2010 dollars) for related surgeries, medications, and procedures. Leiomyomas are reportedly the most frequent reason for hysterectomy.

Robust data on the optimal therapeutic approach to fibroids have been sparse, however, with a 2017 comparative-effectiveness review from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reporting that evidence on leiomyoma treatments was insufficient to guide clinical care. Few well-conducted trials of leiomyoma treatment have directly compared different treatment options, the authors noted.

The rate of myomectomy is reported to be 9.2 per 10,000 woman-years in Black women and 1.3 per 10,000 woman years in White women, and the recurrence rate after myomectomy can be as great as 60% when patients are followed up to 5 years.

The authors said their findings “may be a reference to discuss expectations for treatment outcomes when choosing initial uterus-preserving treatment for leiomyomas, especially for patients receiving treatment years before the likely onset of menopause.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Dr. Lauren Wise is a paid consultant for AbbVie and has received in-kind donations from Swiss Precision Diagnostics and Kindara.com; she has also received payment from the Gates Foundation.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Despite effective therapies, fibroid care still lacking

In 2022, two colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Bhuchitra Singh, MD, MPH, MS, MBA, and James Segars Jr., MD, reviewed the available literature to evaluate the effectiveness of newer minimally invasive therapies in reducing bleeding and improving the quality of life and control of symptoms linked to uterine fibroids.

Their goal, according to Dr. Segars, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the division of women’s health research at Johns Hopkins, was to help guide clinicians and patients in making decisions about the use of the newer therapies, including radiofrequency ablation and ultrasound-guided removal of lesions.

But he and Dr. Singh, the director of clinical research at the Howard W. and Georgeanna Seegar Jones Laboratory of Reproductive Sciences and Women’s Health Research, were surprised by their findings. “The outcomes were relatively the same,” Dr. Segars said. “All of the modalities lead to significant reduction in bleeding and other fibroid-related symptoms.”

The data on long-term complications and risk for recurrence are sparse for some of the newer approaches, and not enough high-quality long-term studies have been conducted for the Food and Drug Administration to approve them as fertility-sparing treatments.

But perhaps, the biggest challenge now is to ensure that women can take advantage of these newer therapies, with large gaps in both the diagnosis of fibroids and geographic access to minimally invasive treatments.

A widespread condition widely underdiagnosed

Uterine fibroids occur in most women (the incidence rises with age) and can be found in up to 70% of women by the time they reach menopause. Risk factors include family history, increasing interval since last birth, hypertension, and obesity. Increasing parity and use of oral contraceptives are protective.

But as many as 50% of cases go undiagnosed, and one reason for this is the failure of clinicians to dig deeply enough into women’s menstrual histories to diagnose fibroids.

“The most common cause of anemia is heavy menstrual bleeding,” said Shannon Laughlin-Tommaso, MD, MPH, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She frequently sees patients who have already undergone colonoscopy to work-up the source of their anemia before anyone suspects that fibroids are the culprit.

“When women tell us about their periods, what they’ve been told is normal [bleeding] – or what they’ve always had and considered normal – is actually kind of on the heavier spectrum,” she said.

Ideally, treatment for uterine fibroids would fix abnormally prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve pain, and ameliorate symptoms associated with an enlarged uterus, such as pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, and constipation. And the fibroids would never recur.

By those measures, hysterectomy fits the bill: Success rates in relieving symptoms are high, and the risk for recurrence is zero. But the procedure carries significant drawbacks: short-term complications of surgery, including infection, bleeding, and injury to the bowels and bladder along with potential long-term risks for cardiovascular disease, cancer, ovarian failure and premature menopause, depression, and decline in cognitive function. Those factors loom even larger for women who still hope to have children.

For that reason, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends myomectomy, or surgical removal of individual fibroids, for women who desire uterine preservation or future pregnancy. And the literature here is solid, according to Dr. Singh, who found that 95% of myomectomy patients achieved control of their bleeding symptoms, whether it was via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, or laparotomy. Up to 40% of women may develop new fibroids, or leiomyomas, within 3 years, although only 12.2% required a second surgery up to after 5 years.

But myomectomy is invasive, requiring general anesthesia, incisions in the uterus, and stitches to close the organ.

Newer techniques have emerged that can effectively treat symptoms of fibroids without requiring surgery. Uterine artery embolization (UAE), which involves passing a catheter into the femoral artery, or laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion can be used to cut off the blood supply of the fibroid. Other techniques, including focused ultrasound surgery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), use various forms of energy to heat and ablate fibroids. The latter two can be performed in outpatient settings and often without general anesthesia.

Approved for use in 1994, UAE has the most data available, with reduction in the volume of fibroids and uterine tissue lasting up to 5 years, and rates of reintervention of 19%-38% between 2 and 5 years after the procedure. Dr. Singh’s review found that 79%-98.5% of recipients of the procedure reported declines in bleeding that persisted for several years, which is comparable to myomectomy. Quality of life and pain scores also showed good improvement, with follow-up in the different studies ranging from 12 months to over 5 years, the analysis showed.

UAE does have its drawbacks. In rare cases, embolization can deprive the entire uterus and ovaries of blood, which can cause ovarian dysfunction and potentially result in premature menopause, although this outcome is most common in women who are older than 45 years. The procedure can often also be painful enough that overnight hospitalization is required.

Focused ultrasound surgeries, which include magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), were approved by the FDA in 2004. Focused ultrasound waves pass through the abdominal wall and produce significant heating, causing a burn that destroys the targeted tissue without damaging surrounding tissue. As with UAE, improvements in fibroid-associated bleeding and measures of quality of life were similar to those after myomectomy up to 3 years later.

But Dr. Singh noted that both focused ultrasound and RFA can damage the skin or internal organs. “[As] always with the thermal interventions, there is the probability of skin as well as internal organs that might get the thermal energy if it’s not focused correctly on to the fibroid itself,” he said. In addition, MRgFUS is not an option for women who are not good candidates to undergo an MRI, such as those with claustrophobia or pacemakers.

Also, with focus ultrasound and RFA, “we do worry about that fibroid getting blood flow back,” which can lead to recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso noted.

Although data on RFA are limited to 12 months of follow-up, most women reported meaningful reductions in bleeding symptoms. Longer follow-up has been reported for bleeding symptoms after MRgFUS, with similar results up to 3 years later.

For Leslie Hansen-Lindner, MD, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., choosing the right procedure starts with a patient-centered conversation weighing the pros and cons of the options and the woman’s goals.

“Is their goal to reduce the size and impact of their fibroid, bleed less, and have a better quality of life on their period?” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “Or is their goal to have the entire fibroid removed?”

If the former, an RFA is appealing to many women. If the latter, laparoscopic or mini-laparotomy myomectomy might be a better choice. Although fewer than 10% of patients require surgical reintervention at 3 years of follow-up for RFA, myomectomy has more consistent long-term evidence showing that fewer women require re-intervention and preserve their fertility, she added.

Age also plays a role in the decision: The closer a woman is to menopause, the less likely she is to experience a recurrence, so a less-invasive procedure is preferable. But for younger women hoping to become pregnant, the lower risk for recurrence and good prognosis for future fertility might sway the choice toward myomectomy.

The first laparoscopic RFA procedures were approved for uterine fibroids in 2012. Dr. Hansen-Lindner is a proponent of transcervical fibroid ablation (TFA), a newer RFA procedure that the FDA approved in 2018. Performed through the cervix, TFA requires no incisions and can generally be done without general anesthesia. Eligible candidates would be any woman with symptomatic fibroids, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, pain, or bulk symptoms. The contraindications are few.

“It’s going to come down to size and location of fibroids, and whether or not they would be accessible by the TFA,” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “I have to make sure that there isn’t a fibroid blocking their cervix and that the fibroids are accessible with this device.”

TFA also is not suitable for removing most submucosal lesions, which typically must be removed by hysteroscopic myomectomy. Dr. Hansen-Lindner said that she often uses TFA in conjunction with hysteroscopic myomectomy for this scenario. Although data on pregnancy after RFA (including TFA), MRgFUS, and HIFU are lacking, Gynesonics, the manufacturer of the Sonata System (the device that delivers radiofrequency energy to shrink the fibroid) has documented 79 pregnancies among the 2,200 women who have undergone TFA in the United States since 2018.

Disparities hampering care

Uterine fibroids are a particular problem for Black women, whose symptoms are more likely to be ignored by clinicians, according to Jodie Katon, PhD, a core investigator at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy. Dr. Katon cited studies in which Black women interviewed about their experiences reported a consistent theme: Clinicians dismissed their symptoms, told them these were nothing to worry about, and advised them to lose weight. Those interactions not only delayed diagnosis among Black women but also led many of them to mistrust clinicians and avoid the health care system altogether.

The failure of clinicians to take their complaints seriously is just one of the disparities affecting Black women. In reviewing the literature, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, who also serves as the associate dean for Education Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Mayo Clinic, found that African American women experience two to three times the risk for fibroids, compared with White women, as well as earlier onset and more severe disease, as measured by number and size of the lesions.

According to Dr. Katon, the etiology of fibroids is still poorly understood. “What we do know is that Black women are disproportionately exposed to a variety of factors that we have shown through observational studies are associated with increased risk of development of uterine fibroids.”

The list includes factors like stress; interpersonal racism; early age at menarche; various indicators of poor diets, such as vitamin D deficiency; the use of certain beauty products, specifically hair straighteners; as well as exposure to air pollution and other environmental toxins.

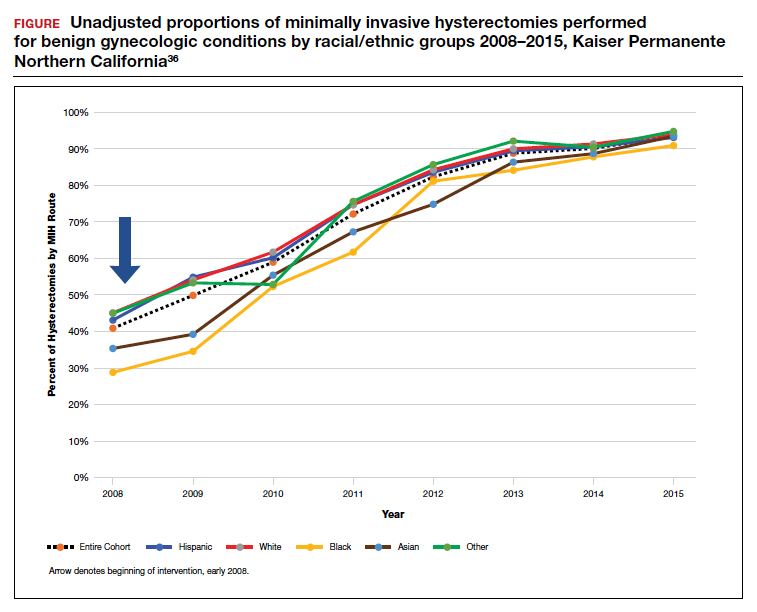

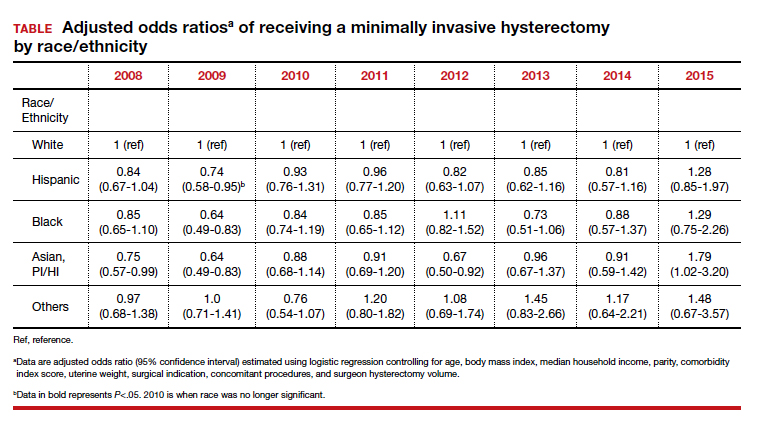

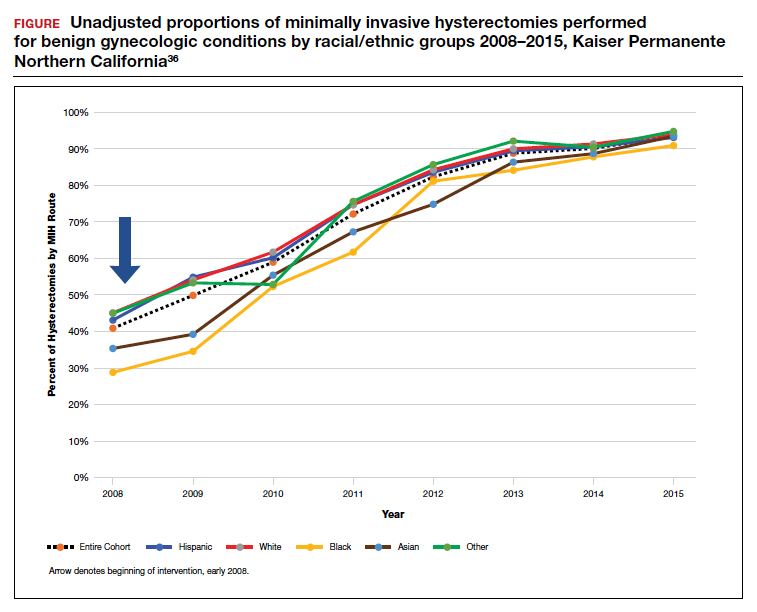

Laughlin-Tommaso also pointed to historical disparities in management, citing a doubled risk for hysterectomy for Black women in a study published in 2007 despite survey data suggesting that Black women report being more interested in uterine-preserving therapies rather than a hysterectomy.

Breaking down barriers of access to new treatments

Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso looked at more recent trends in the management of fibroids using data from the multicenter COMPARE-UF study, which enrolled women between 2015 and 2020 undergoing fibroid treatment into a longitudinal registry to track their outcomes. She found that Black women underwent hysterectomies at a lower rate than did White women and were instead more likely to undergo myomectomy or UAE.

Some of the change may reflect lack of approved minimally invasive procedures before 2000. “But now that we have expanded options, I think most women are opting not to have a hysterectomy,” Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso said.

Dr. Katon has research funding from the VA to look more closely at racial disparities in the treatment of fibroids. In a study published in April 2023, she reported some surprising trends.

During the period from 2010 to 2018, she found that Black veterans diagnosed with fibroids were less likely than White veterans were to receive treatment, regardless of their age or the severity of their symptoms. This finding held even among women with anemia, which should have been a clear indication for treatment.

But, as in the COMPARE-UF study, the subset of Black veterans who received an interventional treatment were less likely than their White peers were to undergo hysterectomy in favor of a fertility-sparing treatment as their initial procedure. Dr. Katon called it a “welcome but unexpected finding.”

But another significant barrier remains: The two newest types of procedures, RFA and guided focused ultrasound, are not commonly performed outside of tertiary care facilities. However, studies have found that all these procedures are cost effective (studies for myomectomy, UAE, MRgFUS, and TFA). The implementation of a category 1 billing code for laparoscopic RFA in 2017 has led more insurance companies to cover the service, and a category 1 code will be available for TFA effective January 2024.

Although RFA does require investment in specialized equipment, which limits facilities from offering the procedure, any gynecologist who routinely performs hysteroscopy can easily learn to do TFA. And the VA, which is committed to eliminating disparities in women’s health, established a 2-year advanced fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery in 2022 to help expand their capacity to offer these procedures.

The VA has been rapidly expanding their gynecology services, and Katon said that she is confident that ultrasound-guided procedures and RFA will become more available within the system. “I would say we’re keeping pace. And in some ways, you know, as a national system we may be positioned to actually outpace the rest of the U.S.”

Dr. Segars reported prior research funding for clinical trials from BioSpecifics Technologies, Bayer, Allergan, AbbVie, and ObsEva and currently receives funding from Myovant Sciences. Dr. Hansen-Lindner reported personal fees from Gynesonics. Dr. Singh, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, and Dr. Katon reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2022, two colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Bhuchitra Singh, MD, MPH, MS, MBA, and James Segars Jr., MD, reviewed the available literature to evaluate the effectiveness of newer minimally invasive therapies in reducing bleeding and improving the quality of life and control of symptoms linked to uterine fibroids.

Their goal, according to Dr. Segars, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the division of women’s health research at Johns Hopkins, was to help guide clinicians and patients in making decisions about the use of the newer therapies, including radiofrequency ablation and ultrasound-guided removal of lesions.

But he and Dr. Singh, the director of clinical research at the Howard W. and Georgeanna Seegar Jones Laboratory of Reproductive Sciences and Women’s Health Research, were surprised by their findings. “The outcomes were relatively the same,” Dr. Segars said. “All of the modalities lead to significant reduction in bleeding and other fibroid-related symptoms.”

The data on long-term complications and risk for recurrence are sparse for some of the newer approaches, and not enough high-quality long-term studies have been conducted for the Food and Drug Administration to approve them as fertility-sparing treatments.

But perhaps, the biggest challenge now is to ensure that women can take advantage of these newer therapies, with large gaps in both the diagnosis of fibroids and geographic access to minimally invasive treatments.

A widespread condition widely underdiagnosed

Uterine fibroids occur in most women (the incidence rises with age) and can be found in up to 70% of women by the time they reach menopause. Risk factors include family history, increasing interval since last birth, hypertension, and obesity. Increasing parity and use of oral contraceptives are protective.

But as many as 50% of cases go undiagnosed, and one reason for this is the failure of clinicians to dig deeply enough into women’s menstrual histories to diagnose fibroids.

“The most common cause of anemia is heavy menstrual bleeding,” said Shannon Laughlin-Tommaso, MD, MPH, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She frequently sees patients who have already undergone colonoscopy to work-up the source of their anemia before anyone suspects that fibroids are the culprit.

“When women tell us about their periods, what they’ve been told is normal [bleeding] – or what they’ve always had and considered normal – is actually kind of on the heavier spectrum,” she said.

Ideally, treatment for uterine fibroids would fix abnormally prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve pain, and ameliorate symptoms associated with an enlarged uterus, such as pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, and constipation. And the fibroids would never recur.

By those measures, hysterectomy fits the bill: Success rates in relieving symptoms are high, and the risk for recurrence is zero. But the procedure carries significant drawbacks: short-term complications of surgery, including infection, bleeding, and injury to the bowels and bladder along with potential long-term risks for cardiovascular disease, cancer, ovarian failure and premature menopause, depression, and decline in cognitive function. Those factors loom even larger for women who still hope to have children.

For that reason, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends myomectomy, or surgical removal of individual fibroids, for women who desire uterine preservation or future pregnancy. And the literature here is solid, according to Dr. Singh, who found that 95% of myomectomy patients achieved control of their bleeding symptoms, whether it was via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, or laparotomy. Up to 40% of women may develop new fibroids, or leiomyomas, within 3 years, although only 12.2% required a second surgery up to after 5 years.

But myomectomy is invasive, requiring general anesthesia, incisions in the uterus, and stitches to close the organ.

Newer techniques have emerged that can effectively treat symptoms of fibroids without requiring surgery. Uterine artery embolization (UAE), which involves passing a catheter into the femoral artery, or laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion can be used to cut off the blood supply of the fibroid. Other techniques, including focused ultrasound surgery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), use various forms of energy to heat and ablate fibroids. The latter two can be performed in outpatient settings and often without general anesthesia.

Approved for use in 1994, UAE has the most data available, with reduction in the volume of fibroids and uterine tissue lasting up to 5 years, and rates of reintervention of 19%-38% between 2 and 5 years after the procedure. Dr. Singh’s review found that 79%-98.5% of recipients of the procedure reported declines in bleeding that persisted for several years, which is comparable to myomectomy. Quality of life and pain scores also showed good improvement, with follow-up in the different studies ranging from 12 months to over 5 years, the analysis showed.

UAE does have its drawbacks. In rare cases, embolization can deprive the entire uterus and ovaries of blood, which can cause ovarian dysfunction and potentially result in premature menopause, although this outcome is most common in women who are older than 45 years. The procedure can often also be painful enough that overnight hospitalization is required.

Focused ultrasound surgeries, which include magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), were approved by the FDA in 2004. Focused ultrasound waves pass through the abdominal wall and produce significant heating, causing a burn that destroys the targeted tissue without damaging surrounding tissue. As with UAE, improvements in fibroid-associated bleeding and measures of quality of life were similar to those after myomectomy up to 3 years later.

But Dr. Singh noted that both focused ultrasound and RFA can damage the skin or internal organs. “[As] always with the thermal interventions, there is the probability of skin as well as internal organs that might get the thermal energy if it’s not focused correctly on to the fibroid itself,” he said. In addition, MRgFUS is not an option for women who are not good candidates to undergo an MRI, such as those with claustrophobia or pacemakers.

Also, with focus ultrasound and RFA, “we do worry about that fibroid getting blood flow back,” which can lead to recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso noted.

Although data on RFA are limited to 12 months of follow-up, most women reported meaningful reductions in bleeding symptoms. Longer follow-up has been reported for bleeding symptoms after MRgFUS, with similar results up to 3 years later.

For Leslie Hansen-Lindner, MD, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., choosing the right procedure starts with a patient-centered conversation weighing the pros and cons of the options and the woman’s goals.

“Is their goal to reduce the size and impact of their fibroid, bleed less, and have a better quality of life on their period?” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “Or is their goal to have the entire fibroid removed?”

If the former, an RFA is appealing to many women. If the latter, laparoscopic or mini-laparotomy myomectomy might be a better choice. Although fewer than 10% of patients require surgical reintervention at 3 years of follow-up for RFA, myomectomy has more consistent long-term evidence showing that fewer women require re-intervention and preserve their fertility, she added.

Age also plays a role in the decision: The closer a woman is to menopause, the less likely she is to experience a recurrence, so a less-invasive procedure is preferable. But for younger women hoping to become pregnant, the lower risk for recurrence and good prognosis for future fertility might sway the choice toward myomectomy.

The first laparoscopic RFA procedures were approved for uterine fibroids in 2012. Dr. Hansen-Lindner is a proponent of transcervical fibroid ablation (TFA), a newer RFA procedure that the FDA approved in 2018. Performed through the cervix, TFA requires no incisions and can generally be done without general anesthesia. Eligible candidates would be any woman with symptomatic fibroids, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, pain, or bulk symptoms. The contraindications are few.

“It’s going to come down to size and location of fibroids, and whether or not they would be accessible by the TFA,” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “I have to make sure that there isn’t a fibroid blocking their cervix and that the fibroids are accessible with this device.”

TFA also is not suitable for removing most submucosal lesions, which typically must be removed by hysteroscopic myomectomy. Dr. Hansen-Lindner said that she often uses TFA in conjunction with hysteroscopic myomectomy for this scenario. Although data on pregnancy after RFA (including TFA), MRgFUS, and HIFU are lacking, Gynesonics, the manufacturer of the Sonata System (the device that delivers radiofrequency energy to shrink the fibroid) has documented 79 pregnancies among the 2,200 women who have undergone TFA in the United States since 2018.

Disparities hampering care

Uterine fibroids are a particular problem for Black women, whose symptoms are more likely to be ignored by clinicians, according to Jodie Katon, PhD, a core investigator at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy. Dr. Katon cited studies in which Black women interviewed about their experiences reported a consistent theme: Clinicians dismissed their symptoms, told them these were nothing to worry about, and advised them to lose weight. Those interactions not only delayed diagnosis among Black women but also led many of them to mistrust clinicians and avoid the health care system altogether.

The failure of clinicians to take their complaints seriously is just one of the disparities affecting Black women. In reviewing the literature, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, who also serves as the associate dean for Education Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Mayo Clinic, found that African American women experience two to three times the risk for fibroids, compared with White women, as well as earlier onset and more severe disease, as measured by number and size of the lesions.

According to Dr. Katon, the etiology of fibroids is still poorly understood. “What we do know is that Black women are disproportionately exposed to a variety of factors that we have shown through observational studies are associated with increased risk of development of uterine fibroids.”

The list includes factors like stress; interpersonal racism; early age at menarche; various indicators of poor diets, such as vitamin D deficiency; the use of certain beauty products, specifically hair straighteners; as well as exposure to air pollution and other environmental toxins.

Laughlin-Tommaso also pointed to historical disparities in management, citing a doubled risk for hysterectomy for Black women in a study published in 2007 despite survey data suggesting that Black women report being more interested in uterine-preserving therapies rather than a hysterectomy.

Breaking down barriers of access to new treatments

Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso looked at more recent trends in the management of fibroids using data from the multicenter COMPARE-UF study, which enrolled women between 2015 and 2020 undergoing fibroid treatment into a longitudinal registry to track their outcomes. She found that Black women underwent hysterectomies at a lower rate than did White women and were instead more likely to undergo myomectomy or UAE.

Some of the change may reflect lack of approved minimally invasive procedures before 2000. “But now that we have expanded options, I think most women are opting not to have a hysterectomy,” Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso said.

Dr. Katon has research funding from the VA to look more closely at racial disparities in the treatment of fibroids. In a study published in April 2023, she reported some surprising trends.

During the period from 2010 to 2018, she found that Black veterans diagnosed with fibroids were less likely than White veterans were to receive treatment, regardless of their age or the severity of their symptoms. This finding held even among women with anemia, which should have been a clear indication for treatment.

But, as in the COMPARE-UF study, the subset of Black veterans who received an interventional treatment were less likely than their White peers were to undergo hysterectomy in favor of a fertility-sparing treatment as their initial procedure. Dr. Katon called it a “welcome but unexpected finding.”

But another significant barrier remains: The two newest types of procedures, RFA and guided focused ultrasound, are not commonly performed outside of tertiary care facilities. However, studies have found that all these procedures are cost effective (studies for myomectomy, UAE, MRgFUS, and TFA). The implementation of a category 1 billing code for laparoscopic RFA in 2017 has led more insurance companies to cover the service, and a category 1 code will be available for TFA effective January 2024.

Although RFA does require investment in specialized equipment, which limits facilities from offering the procedure, any gynecologist who routinely performs hysteroscopy can easily learn to do TFA. And the VA, which is committed to eliminating disparities in women’s health, established a 2-year advanced fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery in 2022 to help expand their capacity to offer these procedures.

The VA has been rapidly expanding their gynecology services, and Katon said that she is confident that ultrasound-guided procedures and RFA will become more available within the system. “I would say we’re keeping pace. And in some ways, you know, as a national system we may be positioned to actually outpace the rest of the U.S.”

Dr. Segars reported prior research funding for clinical trials from BioSpecifics Technologies, Bayer, Allergan, AbbVie, and ObsEva and currently receives funding from Myovant Sciences. Dr. Hansen-Lindner reported personal fees from Gynesonics. Dr. Singh, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, and Dr. Katon reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2022, two colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Bhuchitra Singh, MD, MPH, MS, MBA, and James Segars Jr., MD, reviewed the available literature to evaluate the effectiveness of newer minimally invasive therapies in reducing bleeding and improving the quality of life and control of symptoms linked to uterine fibroids.

Their goal, according to Dr. Segars, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the division of women’s health research at Johns Hopkins, was to help guide clinicians and patients in making decisions about the use of the newer therapies, including radiofrequency ablation and ultrasound-guided removal of lesions.

But he and Dr. Singh, the director of clinical research at the Howard W. and Georgeanna Seegar Jones Laboratory of Reproductive Sciences and Women’s Health Research, were surprised by their findings. “The outcomes were relatively the same,” Dr. Segars said. “All of the modalities lead to significant reduction in bleeding and other fibroid-related symptoms.”

The data on long-term complications and risk for recurrence are sparse for some of the newer approaches, and not enough high-quality long-term studies have been conducted for the Food and Drug Administration to approve them as fertility-sparing treatments.

But perhaps, the biggest challenge now is to ensure that women can take advantage of these newer therapies, with large gaps in both the diagnosis of fibroids and geographic access to minimally invasive treatments.

A widespread condition widely underdiagnosed

Uterine fibroids occur in most women (the incidence rises with age) and can be found in up to 70% of women by the time they reach menopause. Risk factors include family history, increasing interval since last birth, hypertension, and obesity. Increasing parity and use of oral contraceptives are protective.

But as many as 50% of cases go undiagnosed, and one reason for this is the failure of clinicians to dig deeply enough into women’s menstrual histories to diagnose fibroids.

“The most common cause of anemia is heavy menstrual bleeding,” said Shannon Laughlin-Tommaso, MD, MPH, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. She frequently sees patients who have already undergone colonoscopy to work-up the source of their anemia before anyone suspects that fibroids are the culprit.

“When women tell us about their periods, what they’ve been told is normal [bleeding] – or what they’ve always had and considered normal – is actually kind of on the heavier spectrum,” she said.

Ideally, treatment for uterine fibroids would fix abnormally prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding, relieve pain, and ameliorate symptoms associated with an enlarged uterus, such as pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, and constipation. And the fibroids would never recur.

By those measures, hysterectomy fits the bill: Success rates in relieving symptoms are high, and the risk for recurrence is zero. But the procedure carries significant drawbacks: short-term complications of surgery, including infection, bleeding, and injury to the bowels and bladder along with potential long-term risks for cardiovascular disease, cancer, ovarian failure and premature menopause, depression, and decline in cognitive function. Those factors loom even larger for women who still hope to have children.

For that reason, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends myomectomy, or surgical removal of individual fibroids, for women who desire uterine preservation or future pregnancy. And the literature here is solid, according to Dr. Singh, who found that 95% of myomectomy patients achieved control of their bleeding symptoms, whether it was via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, or laparotomy. Up to 40% of women may develop new fibroids, or leiomyomas, within 3 years, although only 12.2% required a second surgery up to after 5 years.

But myomectomy is invasive, requiring general anesthesia, incisions in the uterus, and stitches to close the organ.

Newer techniques have emerged that can effectively treat symptoms of fibroids without requiring surgery. Uterine artery embolization (UAE), which involves passing a catheter into the femoral artery, or laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion can be used to cut off the blood supply of the fibroid. Other techniques, including focused ultrasound surgery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), use various forms of energy to heat and ablate fibroids. The latter two can be performed in outpatient settings and often without general anesthesia.

Approved for use in 1994, UAE has the most data available, with reduction in the volume of fibroids and uterine tissue lasting up to 5 years, and rates of reintervention of 19%-38% between 2 and 5 years after the procedure. Dr. Singh’s review found that 79%-98.5% of recipients of the procedure reported declines in bleeding that persisted for several years, which is comparable to myomectomy. Quality of life and pain scores also showed good improvement, with follow-up in the different studies ranging from 12 months to over 5 years, the analysis showed.

UAE does have its drawbacks. In rare cases, embolization can deprive the entire uterus and ovaries of blood, which can cause ovarian dysfunction and potentially result in premature menopause, although this outcome is most common in women who are older than 45 years. The procedure can often also be painful enough that overnight hospitalization is required.

Focused ultrasound surgeries, which include magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), were approved by the FDA in 2004. Focused ultrasound waves pass through the abdominal wall and produce significant heating, causing a burn that destroys the targeted tissue without damaging surrounding tissue. As with UAE, improvements in fibroid-associated bleeding and measures of quality of life were similar to those after myomectomy up to 3 years later.

But Dr. Singh noted that both focused ultrasound and RFA can damage the skin or internal organs. “[As] always with the thermal interventions, there is the probability of skin as well as internal organs that might get the thermal energy if it’s not focused correctly on to the fibroid itself,” he said. In addition, MRgFUS is not an option for women who are not good candidates to undergo an MRI, such as those with claustrophobia or pacemakers.

Also, with focus ultrasound and RFA, “we do worry about that fibroid getting blood flow back,” which can lead to recurrence of heavy menstrual bleeding, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso noted.

Although data on RFA are limited to 12 months of follow-up, most women reported meaningful reductions in bleeding symptoms. Longer follow-up has been reported for bleeding symptoms after MRgFUS, with similar results up to 3 years later.

For Leslie Hansen-Lindner, MD, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., choosing the right procedure starts with a patient-centered conversation weighing the pros and cons of the options and the woman’s goals.

“Is their goal to reduce the size and impact of their fibroid, bleed less, and have a better quality of life on their period?” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “Or is their goal to have the entire fibroid removed?”

If the former, an RFA is appealing to many women. If the latter, laparoscopic or mini-laparotomy myomectomy might be a better choice. Although fewer than 10% of patients require surgical reintervention at 3 years of follow-up for RFA, myomectomy has more consistent long-term evidence showing that fewer women require re-intervention and preserve their fertility, she added.

Age also plays a role in the decision: The closer a woman is to menopause, the less likely she is to experience a recurrence, so a less-invasive procedure is preferable. But for younger women hoping to become pregnant, the lower risk for recurrence and good prognosis for future fertility might sway the choice toward myomectomy.

The first laparoscopic RFA procedures were approved for uterine fibroids in 2012. Dr. Hansen-Lindner is a proponent of transcervical fibroid ablation (TFA), a newer RFA procedure that the FDA approved in 2018. Performed through the cervix, TFA requires no incisions and can generally be done without general anesthesia. Eligible candidates would be any woman with symptomatic fibroids, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, pain, or bulk symptoms. The contraindications are few.

“It’s going to come down to size and location of fibroids, and whether or not they would be accessible by the TFA,” Dr. Hansen-Lindner said. “I have to make sure that there isn’t a fibroid blocking their cervix and that the fibroids are accessible with this device.”

TFA also is not suitable for removing most submucosal lesions, which typically must be removed by hysteroscopic myomectomy. Dr. Hansen-Lindner said that she often uses TFA in conjunction with hysteroscopic myomectomy for this scenario. Although data on pregnancy after RFA (including TFA), MRgFUS, and HIFU are lacking, Gynesonics, the manufacturer of the Sonata System (the device that delivers radiofrequency energy to shrink the fibroid) has documented 79 pregnancies among the 2,200 women who have undergone TFA in the United States since 2018.

Disparities hampering care

Uterine fibroids are a particular problem for Black women, whose symptoms are more likely to be ignored by clinicians, according to Jodie Katon, PhD, a core investigator at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy. Dr. Katon cited studies in which Black women interviewed about their experiences reported a consistent theme: Clinicians dismissed their symptoms, told them these were nothing to worry about, and advised them to lose weight. Those interactions not only delayed diagnosis among Black women but also led many of them to mistrust clinicians and avoid the health care system altogether.

The failure of clinicians to take their complaints seriously is just one of the disparities affecting Black women. In reviewing the literature, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, who also serves as the associate dean for Education Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Mayo Clinic, found that African American women experience two to three times the risk for fibroids, compared with White women, as well as earlier onset and more severe disease, as measured by number and size of the lesions.

According to Dr. Katon, the etiology of fibroids is still poorly understood. “What we do know is that Black women are disproportionately exposed to a variety of factors that we have shown through observational studies are associated with increased risk of development of uterine fibroids.”

The list includes factors like stress; interpersonal racism; early age at menarche; various indicators of poor diets, such as vitamin D deficiency; the use of certain beauty products, specifically hair straighteners; as well as exposure to air pollution and other environmental toxins.

Laughlin-Tommaso also pointed to historical disparities in management, citing a doubled risk for hysterectomy for Black women in a study published in 2007 despite survey data suggesting that Black women report being more interested in uterine-preserving therapies rather than a hysterectomy.

Breaking down barriers of access to new treatments

Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso looked at more recent trends in the management of fibroids using data from the multicenter COMPARE-UF study, which enrolled women between 2015 and 2020 undergoing fibroid treatment into a longitudinal registry to track their outcomes. She found that Black women underwent hysterectomies at a lower rate than did White women and were instead more likely to undergo myomectomy or UAE.

Some of the change may reflect lack of approved minimally invasive procedures before 2000. “But now that we have expanded options, I think most women are opting not to have a hysterectomy,” Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso said.

Dr. Katon has research funding from the VA to look more closely at racial disparities in the treatment of fibroids. In a study published in April 2023, she reported some surprising trends.

During the period from 2010 to 2018, she found that Black veterans diagnosed with fibroids were less likely than White veterans were to receive treatment, regardless of their age or the severity of their symptoms. This finding held even among women with anemia, which should have been a clear indication for treatment.

But, as in the COMPARE-UF study, the subset of Black veterans who received an interventional treatment were less likely than their White peers were to undergo hysterectomy in favor of a fertility-sparing treatment as their initial procedure. Dr. Katon called it a “welcome but unexpected finding.”

But another significant barrier remains: The two newest types of procedures, RFA and guided focused ultrasound, are not commonly performed outside of tertiary care facilities. However, studies have found that all these procedures are cost effective (studies for myomectomy, UAE, MRgFUS, and TFA). The implementation of a category 1 billing code for laparoscopic RFA in 2017 has led more insurance companies to cover the service, and a category 1 code will be available for TFA effective January 2024.

Although RFA does require investment in specialized equipment, which limits facilities from offering the procedure, any gynecologist who routinely performs hysteroscopy can easily learn to do TFA. And the VA, which is committed to eliminating disparities in women’s health, established a 2-year advanced fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery in 2022 to help expand their capacity to offer these procedures.

The VA has been rapidly expanding their gynecology services, and Katon said that she is confident that ultrasound-guided procedures and RFA will become more available within the system. “I would say we’re keeping pace. And in some ways, you know, as a national system we may be positioned to actually outpace the rest of the U.S.”

Dr. Segars reported prior research funding for clinical trials from BioSpecifics Technologies, Bayer, Allergan, AbbVie, and ObsEva and currently receives funding from Myovant Sciences. Dr. Hansen-Lindner reported personal fees from Gynesonics. Dr. Singh, Dr. Laughlin-Tommaso, and Dr. Katon reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fibroids: Growing management options for a prevalent problem

OBG Manag. 33(12). | doi 10.12788/obgm.0169

Fibroids: Is surgery the only management approach?

Two chronic gynecologic conditions notably affect a woman’s quality of life (QoL), including fertility – one is endometriosis, and the other is a fibroid uterus. For a benign tumor, fibroids have an impressive prevalence found in approximately 50%-60% of women during their reproductive years. By menopause, it is estimated that 70% of woman have a fibroid, yet the true incidence is unknown given that only 25% of women experience symptoms bothersome enough to warrant intervention. This month’s article reviews the burden of fibroids and the latest management options that may potentially avoid surgery.

Background

Fibroids are monoclonal tumors of uterine smooth muscle that originate from the myometrium. Risk factors include family history, being premenopausal, increasing time since last delivery, obesity, and hypertension (ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 228 Jun 2021: Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun 1;137[6]:e100-e15) but oral hormonal contraception, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), and increased parity reduce the risk of fibroids. Compared with White women, Black women have a 2-3 times higher prevalence of fibroids, develop them at a younger age, and present with larger fibroids.

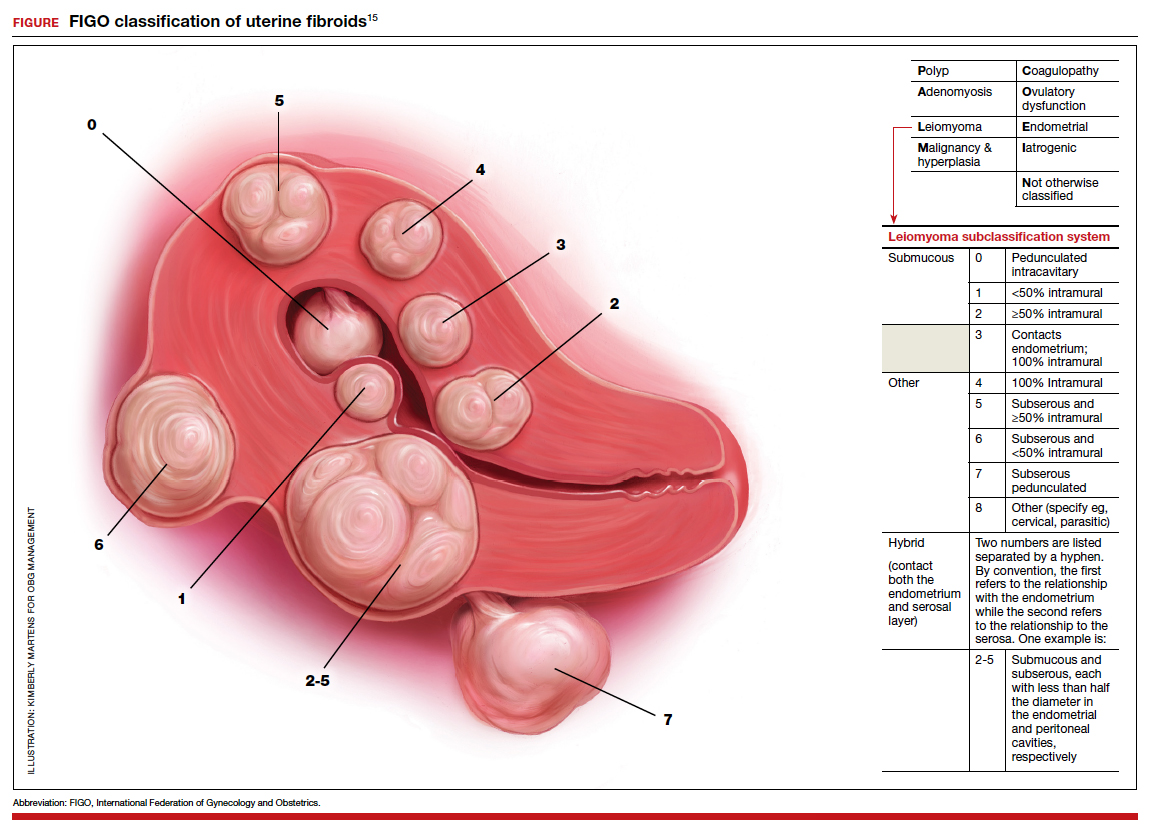

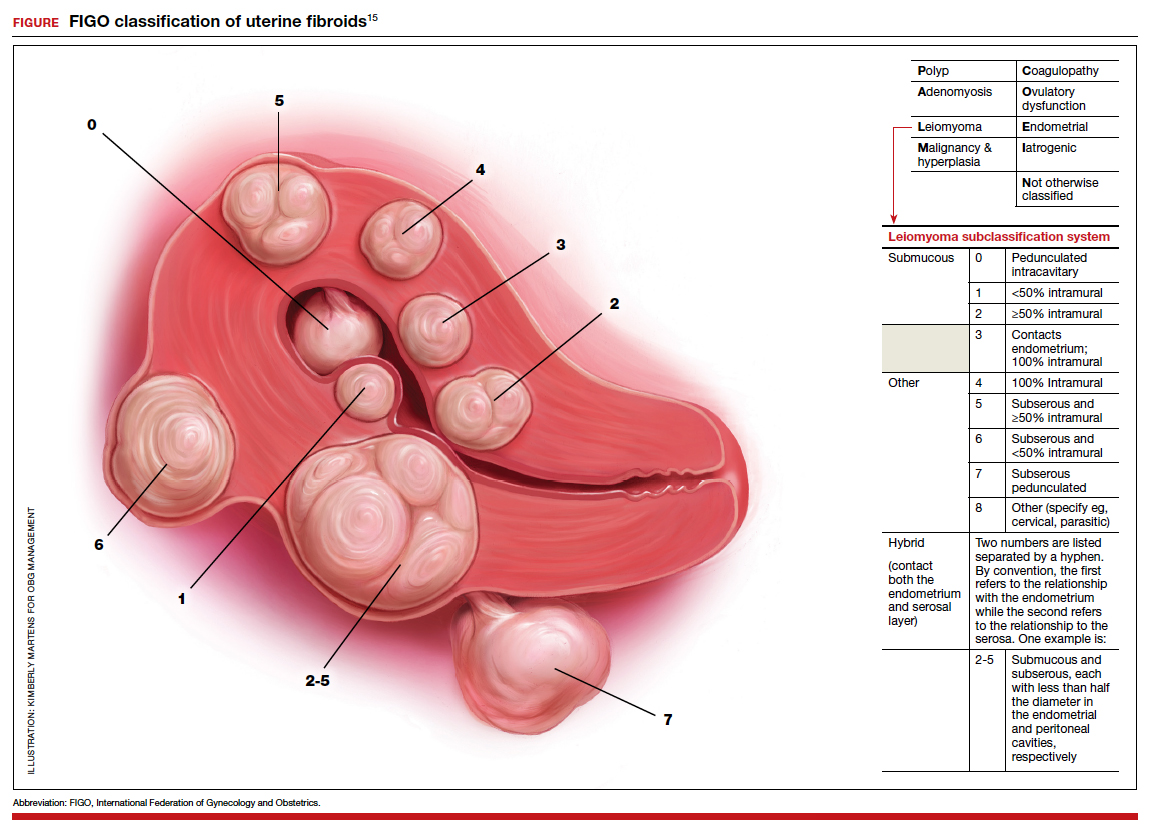

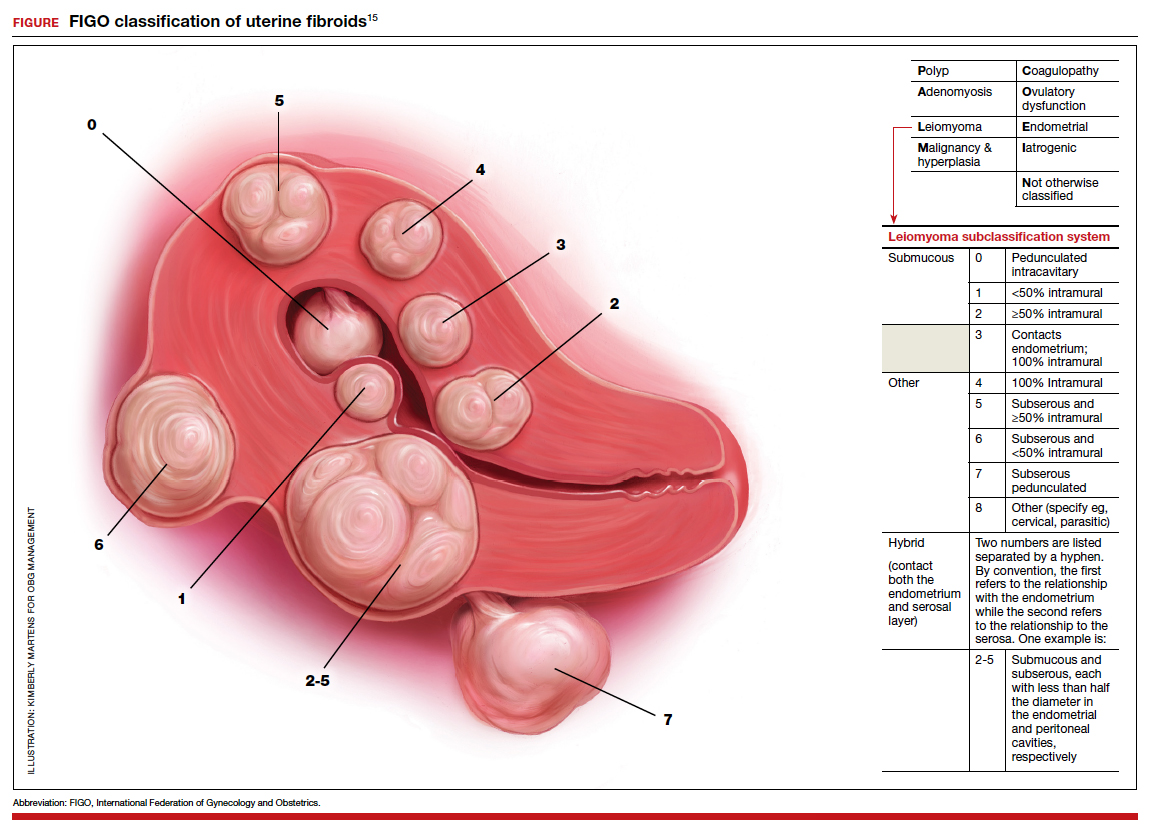

The FIGO leiomyoma classification is the agreed upon system for identifying fibroid location. Symptoms are all too familiar to gynecologists, with life-threatening hemorrhage with severe anemia being the most feared, particularly for FIGO types 1-5. Transvaginal ultrasound is the simplest imaging tool for evaluation.

Fibroids and fertility

Fibroids can impair fertility in several ways: alteration of local anatomy, including the detrimental effects of abnormal uterine bleeding; functional changes by increasing uterine contractions and impairing endometrium and myometrial blood supply; and changes to the local hormonal environment that could impair egg/sperm transport, or embryo implantation (Hum Reprod Update. 2017;22:665-86).

Prior to consideration of surgery, saline infusion sonogram can determine the degree of impact on the endometrium, which is most applicable to the infertility patient, but can also allow guidance toward the appropriate surgical approach.

Treatment options – medical

Management of fibroids is based on a woman’s age, desire for fertility, symptoms, and location of the fibroid(s). Expectant observation of a woman with fibroids may be a reasonable approach, provided the lack of symptoms impairing QoL and of anemia. Typically, there is no change in fibroid size during the short term, considered less than 1 year. Regarding fertility, studies are heterogeneous so there is no definitive conclusion that fibroids impair natural fertility (Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43:100-10). Spontaneous regression, defined by a reduction in fibroid volume of greater than 20%, has been noted to occur in 7.0% of fibroids (Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2018;7[3]:117-21).

When fertility is not desired, medical management of fibroids is the initial conservative approach. GnRH agonists have been utilized for temporary relief of menometrorrhagia because of fibroids and to reduce their volume, particularly preoperatively. However, extended treatment can induce bone mineral density loss. Add-back therapy (tibolone, raloxifene, estriol, and ipriflavone) is of value in reducing bone loss while MPA and tibolone may manage vasomotor symptoms. More recently, the use of a GnRH antagonist (elagolix) along with add-back therapy has been approved for up to 24 months by the Food and Drug Administration and has demonstrated a more than 50% amenorrhea rate at 12 months (Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1313-26).

Progesterone plays an important role in fibroid growth, but the mechanism is unclear. Although not FDA approved, selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRM) act directly on fibroid size reduction at the level of the pituitary to induce amenorrhea through inhibition of ovulation. Also, more than one course of SPRMs can provide benefit for bleeding control and volume reduction. The SPRM ulipristal acetate for four courses of 3 months demonstrated 73.5% of patients experienced a fibroid volume reduction of greater than 25% and were amenorrheic (Fertil Steril. 2017;108:416-25). GnRH agonists or SPRMs may benefit women if the fibroid is larger than 3 cm or anemia exists, thereby precluding immediate surgery.

Other medication options include the levonorgestrel IUD, combined hormonal contraceptives, and tranexamic acid – all of which have limited data on effective results of treating abnormal uterine bleeding.

Treatment options – surgical

Fibroids are the most common reason for hysterectomy as they are the contributing indication in approximately one-third of surgeries. When future fertility is desired, current surgical options include hysteroscopic and laparoscopic (including robotic) myomectomy. Hysteroscopy is the standard approach for FIGO type 1 fibroids and can also manage some type 2 fibroids provided they are less than 3 cm and the latter is greater than 5 mm from the serosa. Type 2 fibroids may benefit from a “two-step” removal to allow the myometrium to contract and extrude the fibroid. In light of the risk of fluid overload with nonelectrolyte solutions that enable the use of monopolar cautery, many procedures are now performed with bipolar cautery or morcellators.

Laparoscopy (including robotic) has outcomes similar to those of laparotomy although the risk of uterine rupture with the former requires careful attention to thorough closure of the myometrial defect. Robotic myomectomy has outcomes similar to those of standard laparoscopy with less blood loss, but operating times may be prolonged (Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;46:113-9).

The rate of myomectomy is reported to be 9.2 per 10,000 woman-years in Black women and 1.3 per 10,000 woman years in White women (Fertil Steril 2017;108;416-25). The rate of recurrence after myomectomy can be as great as 60% when patients are followed up to 5 years. Intramural fibroids greater than 2.85 cm and not distorting the uterine cavity may decrease in vitro fertilization (IVF) success (Fertil Steril 2014;101:716-21).

Noninvasive treatment modalities