User login

Using social media to change the story on MIGS

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Endometriosis is one of the more daunting diagnoses that gynecologists treat. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by

First-time evaluation

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: When a patient presents to your practice for the first time and you suspect endometriosis, what considerations tailor your evaluation, and what does that evaluation involve?

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: The diagnosis is contingent on a patient’s presenting profile. How symptomatic is she? How old is she? What are her reproductive goals? The gold standard for diagnosis is a histologic diagnosis, which is surgical. Depending on the age profile, however, and how close she is to menopause, the patient may be managed medically. Even women in the young reproductive age group may be managed medically if symptoms are responsive to medical treatment.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I agree. When a patient presents without a laparoscopy, or a tissue diagnosis, but the symptoms are consistent with likely endometriosis (depending on where she is in her reproductive cycle and what her goals are), I think treating with a first-line therapy—hormonal treatments such as progestin-only oral contraceptive pills—is acceptable. I usually conduct a treatment trial period of 3 to 6 months to see if she obtains any symptom relief.

If that first-line treatment fails, generally you can move to a second-line treatment.

I have a discussion in which I either offer a second-line treatment, such as medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) or leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot), or get a tissue diagnosis, if possible, by performing laparoscopy. If first-line or even second-line therapy fails, you need to consider doing a diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm or deny the diagnosis.

Dr. Advincula: Are there any points in the evaluation of a patient who visits your practice for the first time where you would immediately offer a surgical approach, as opposed to starting with medical management?

Dr. Hur: A large percentage of my patients undergo surgical evaluation, as surgical diagnosis is the gold standard. If you look at the literature, even among surgeons, the accuracy of visual diagnosis is not great.1,2 I target individuals who are either not responsive to medical treatment or who have never tried medical treatment but are trying to conceive, so they are not medical candidates, or individuals who genuinely want a diagnosis for surgical management—sometimes even before first-line medical treatment.

Dr. Brown: Your examination sometimes also dictates your approach. A patient may never have had a laparoscopy or hormone therapy, but if you find uterosacral ligament nodularity, extreme pain on examination, and suspicious findings on ultrasound or otherwise, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis.

Endometrioma management

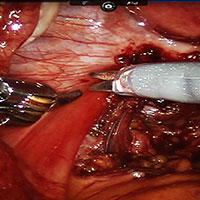

Dr. Advincula: Let’s jump ahead. You have decided to proceed with laparoscopy and you encounter an endometrioma. What is your management strategy, particularly in a fertility-desiring patient?

Dr. Hur: Even if a woman has not undergone first-line medical treatment, if she is trying to conceive or presents with infertility, it’s a different balancing act for approaching the patient. When a woman presents, either with an ultrasound finding or an intraoperative finding of an endometrioma, I am a strong advocate of treating symptomatic disease, which means complete cyst excision. Good clinical data suggest that reproductive outcomes are improved for spontaneous pregnancy rates when you excise an endometrioma.3-6

Dr. Advincula: What are the risks of excision of an endometrioma cyst that patients need to know about?

Dr. Brown: Current standard of care is cystectomy, stripping the cyst wall away from the ovarian cortex. There is some concern that the stripping process, depending on how long the endometrioma has been present within the ovary, can cause some destruction to the underlying oocytes and perhaps impact that ovary’s ability to produce viable eggs.

Some studies, from France in particular, have investigated different energy sources, such as plasma energy, that make it possible to remove part of the cyst and then use the plasma energy to vaporize the rest of the cyst wall that may be lying on the cortex. Researchers looked at anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there does seem to be a difference in terms of how you remove the cyst.7-9 This energy source is not available to everyone; it’s similar to laser but does not have as much penetration. Standard of care is still ovarian stripping.

The conversation with the patient—if she is already infertile and this cyst is a problem—would be that it likely needs to be removed. There is a chance that she may need assisted reproduction; she might not be able to get pregnant on her own due either to the presence of the endometrioma or to the surgical process of removing it and stripping.

Dr. Advincula: How soon after surgery can a patient start to pursue trying to get pregnant?

Dr. Hur: I think there is no time restraint outside of recovery. As long as the patient has a routine postoperative course, she can try to conceive, spontaneously or with assisted reproduction. Some data suggest, however, that ovarian reserve is diminished immediately after surgery.10–12 If you look at the spontaneous clinical pregnancy outcomes, they are comparable 3 to 6 months postsurgery.4,12–14

Dr. Brown: I agree. Time is of the essence with a lot of patients, many of whom present after age 35.

Dr. Hur: It’s also important to highlight that there are 2 presentations with endometrioma: the symptomatic patient and the asymptomatic patient. In the asymptomatic patient, her age, reproductive goals, and the bilaterality (whether it is present on both sides or on one side) of the endometrioma are important in deciding on a patient-centered surgical plan. For someone with a smaller cyst, unilateral presentation, and maybe older age at presentation, it may or may not impact assisted reproductive outcomes.

If the patient is not symptomatic and she is older with bilateral endometriomas less than 4 cm, some data suggest that patient might be better served in a conservative fashion.6,15–17 Then, once she is done with assisted reproduction, we might be more aggressive surgically by treating the finding that would not resolve spontaneously without surgical management. It is important to highlight that endometriomas do not resolve on their own; they require surgical management.

Read about managing endometriosis for the patient not seeking fertility

Endometriosis management for the patient not seeking fertility

Dr. Advincula: Let’s now consider a patient on whom you have performed laparoscopy not only to diagnose and confirm the evidence of endometriosis but also to treat endometriosis, an endometrioma, and potentially deeply infiltrative disease. But this person is not trying to get pregnant. Postoperatively, what is your approach?

Dr. Brown: Suppressive therapy for this patient could be first-line or second-line therapy, such as a Lupron Depot or Depo-Provera. We keep the patient on suppressive therapy (whatever treatments work for her), until she’s ready to get pregnant; then we take her off. Hopefully she gets pregnant. After she delivers, we reinitiate suppressive therapy. I will follow these women throughout their reproductive cycle, and I think having a team of physicians who are all on the same page can help this patient manage her disease through her reproductive years.

Dr. Hur: If a patient presented warranting surgical management once, and she is not menopausal, the likelihood that disease will recur is quite high. Understanding the nature and the pathology of the disease, hormonal suppression would be warranted. Suppression is not just for between pregnancies, it’s until the patient reaches natural menopause. It’s also in the hopes of suppressing the disease so she does not need recurrent surgeries.

We typically do not operate unless patients have recurrence of symptoms that no longer respond to medical therapy. Our hope is to buy them more time closer to the age of natural menopause so that medical repercussions do not result in hysterectomy and ovary removal, which have other nongynecologic manifestations, including negative impact on bone and cardiac health.

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: I am a strong advocate of excision of endometriosis. I believe that it's essential to excise for 2 very important reasons. One reason is for diagnosis. Accurately diagnosing endometriosis through visualization alone is poor, even among gynecologic surgeons. It is very important to have an accurate diagnosis of endometriosis, since the diagnosis will then dictate the treatment for the rest of a patient's reproductive life.

The second reason that excision is essential is because you just do not know how much disease there is "behind the scenes." When you start to excise, you begin to appreciate the depth of the disease, and often fibrosis or inflammation is present even behind the endometriosis implant that is visualized.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I approach endometriosis in the same way that an oncologist would approach cancer. I call it cytoreduction--reducing the disease. There is this iceberg phenomenon, where the tip of the iceberg is seen in the water, but you have no idea how deep it actually goes. That is very much deep, infiltrative endometriosis. Performing an ablation on the top does almost nothing for the patient and may actually complicate the situation by causing scar tissue. If a patient has symptoms, I firmly believe that you must resect the disease, whether it is on the peritoneum, bladder, bowel, or near the ureter. Now, these are radical surgeries, and not every patient should have a radical surgery. It is very much based on the patient's pain complaints and issues at that time, but excision of endometriosis really, in my opinion, should be the standard of care.

Risks of excision of endometriosis

Dr. Brown: The risks of disease excision depend on whether a patient has ureteral disease, bladder disease, or bowel disease, suggested through a preoperative or another operative report or imaging. If this is the case, we have a preoperative discussion with the patient about, "To what extent do you want me to go to remove the disease from your pelvis? If I remove it from your peritoneum and your bladder, there is the chance that you'll have to go home with a Foley catheter for a few days. If the bowel is involved, do you want me to try to resect the disease or shave it off the bowel? If we get into a problem, are you okay with me resecting that bowel?" These are the issues that we have to discuss, because there are potential complications, although known.

The role of the LNG-IUD

Dr. Advincula: Something that often comes up is the role of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) as one therapy option, either preoperatively or postoperatively. What is your perspective?

Dr. Hur: I reserve the LNG-IUD as a second-line therapy for patients, predominantly because it allows direct delivery of the medication to the womb (rather than systemic exposure of the medication). For patients who experience adverse effects due to systemic exposure to first-line treatments, it might be a great option. However, I do not believe that it consistently suppresses the ovaries, which we understand feeds the pathology of the hormonal stimulation, and so typically I will reserve it as a second-line treatment.

Dr. Brown: I utilize the LNG-IUD in a similar fashion. I may have patients who have had a diagnostic laparoscopy somewhere else and were referred to me because they now have known stage 3 or 4 endometriosis without endometriomas. Those patients, if they are going to need suppressive therapy after surgery and are not ready to get pregnant, do very well with the LNG-IUD, and I will place it during surgery under anesthesia. If a patient has endometriomas seen at the time of surgery, we could still place an LNG-IUD at the time of surgery. We may need to add on an additional medication, however, like another oral progesterone. I do have patients that use both an IUD and either combined oral contraceptive pills and/or oral progestins. Those patients usually have complicated cases with very deep infiltrative disease.

Read about managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Dr. Advincula: Patients often are quite concerned when the words “endometriosis” and “bowel” come together. How do you manage disease that involves the bowel?

Dr. Hur: A lot of patients with endometriosis have what I call neighboring disease—it’s not limited just to the pelvis, but it involves the neighboring organs including the bowel and bladder. Patients can present with symptoms related to those adjacent organs. However, not all disease involving the bowel or bladder manifests with symptoms, and patients with symptoms may not have visible disease.

Typically, when a patient presents with symptoms of bowel involvement, where the bowel lumen is narrowed to more than 50% and/or she has functional manifestations (signs of obstruction that result in abnormal bowel function), we have serious conversations about a bowel resection. If she has full-thickness disease without significant bowel dysfunction—other than blood in her stool—sometimes we talk about more conservative treatment because of the long-term manifestations that a bowel resection could have.

Dr. Brown: I agree completely. It is important to have a good relationship with our colorectal surgeons. If I suspect that the patient has narrowing of the lumen of the large bowel or she actually has symptoms such as bloody diarrhea during menstruation—which is suggestive of deep, infiltrative and penetrative disease—I will often order a colonoscopy ahead of time to get confirmed biopsies. Then the patient discussion occurs with our colorectal surgeon, who operates with me jointly if we decide to proceed with a bowel resection. It’s important to have subspecialty colleagues involved in this care, because a low anterior resection is a very big surgery and there can be down-the-stream complications.

The importance of multidisciplinary care

Dr. Advincula: What are your perspectives on a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to the patient with endometriosis?

Dr. Brown: As I previously mentioned, it is important to develop a good relationship with colorectal surgery/urology. In addition, behavioral therapists may be involved in the care of patients with endometriosis, for a number of reasons. The disease process is fluid. It will change during the patient’s reproductive years, and you need to manage it accordingly based on her symptoms. Sometimes the diagnosis is not made for 5 to 10 years, and that can lead to other issues: depression, fibromyalgia, or irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient may have multiple issues plus endometriosis. I think having specialists such as gastroenterologists and behavioral therapists on board, as well as colorectal and urological surgeons who can perform these complex surgeries, is very beneficial to the patient. That way, she benefits from the team’s focus and is cared for from start to finish.

Dr. Hur: I like to call the abdomen a studio. It does not have separate compartments for each organ system. It’s one big room, and often the neighboring organs are involved, including the bowel and bladder. I think Dr. Brown’s observation—the multidisciplinary approach to a patient’s comprehensive care—is critical. Like any surgery, preoperative planning and preoperative assessment are essential, and these steps should include the patient. The discussion should cover not only the surgical outcomes that the surgeons expect, but also what the patient expects to be improved. For example, for patients with extensive disease and bowel involvement, a bowel resection is not always the right approach because it can have potential long-term sequelae. Balancing the risks associated with surgery with the long-term benefits is an important part of the discussion.

Dr. Advincula: Those are both excellent perspectives. Endometriosis is a very complicated disease state, does require a multidisciplinary approach to management, and there are implications and strategies that involve both the medical approach to management and the surgical approach.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2004;111(11):1204–1212.

- Fernando S, Soh PQ, Cooper M, et al. Reliability of visual diagnosis of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):783–789.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1176–1180.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004992.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

- Stochino-Loi E, Darwish B, Mircea O, et al. Does preoperative antimüllerian hormone level influence postoperative pregnancy rate in women undergoing surgery for severe endometriosis? Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):707–713.e3.

- Motte I, Roman H, Clavier B, et al. In vitro fertilization outcomes after ablation of endometriomas using plasma energy: A retrospective case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2016;44(10):541–547.

- Roman H, Bubenheim M, Auber M, Marpeau L, Puscasiu L. Antimullerian hormone level and endometrioma ablation using plasma energy. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

- Saito N, Okuda K, Yuguchi H, Yamashita Y, Terai Y, Ohmichi M. Compared with cystectomy, is ovarian vaporization of endometriotic cysts truly more effective in maintaining ovarian reserve? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):804–810.

- Giampaolino P, Bifulco G, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mercorio A, Bruzzese D, Di Carlo C. Endometrioma size is a relevant factor in selection of the most appropriate surgical technique: a prospective randomized preliminary study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;195:88–93.

- Chang HJ, Han SH, Lee JR, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: serial changes of serum anti-MTimes New Romanüllerian hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):343–349.

- Ding Y, Yuan Y, Ding J, Chen Y, Zhang X, Hua K. Comprehensive assessment of the impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(7):1252–1259.

- Mircea O, Puscasiu L, Resch B, et al. Fertility outcomes after ablation using plasma energy versus cystectomy in infertile women with ovarian endometrioma: A multicentric comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(7):1138–1145.

- Ozaki R, Kumakiri J, Tinelli A, Grimbizis GF, Kitade M, Takeda S. Evaluation of factors predicting diminished ovarian reserve before and after laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas: a prospective cohort study. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9(1):37.

- Demirol A, Guven S, Baykal C, Gurgan T. Effect of endometrioma cystectomy on IVF outcome: A prospective randomized study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12(5):639–643.

- Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, et al; ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704.

Endometriosis is one of the more daunting diagnoses that gynecologists treat. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by

First-time evaluation

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: When a patient presents to your practice for the first time and you suspect endometriosis, what considerations tailor your evaluation, and what does that evaluation involve?

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: The diagnosis is contingent on a patient’s presenting profile. How symptomatic is she? How old is she? What are her reproductive goals? The gold standard for diagnosis is a histologic diagnosis, which is surgical. Depending on the age profile, however, and how close she is to menopause, the patient may be managed medically. Even women in the young reproductive age group may be managed medically if symptoms are responsive to medical treatment.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I agree. When a patient presents without a laparoscopy, or a tissue diagnosis, but the symptoms are consistent with likely endometriosis (depending on where she is in her reproductive cycle and what her goals are), I think treating with a first-line therapy—hormonal treatments such as progestin-only oral contraceptive pills—is acceptable. I usually conduct a treatment trial period of 3 to 6 months to see if she obtains any symptom relief.

If that first-line treatment fails, generally you can move to a second-line treatment.

I have a discussion in which I either offer a second-line treatment, such as medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) or leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot), or get a tissue diagnosis, if possible, by performing laparoscopy. If first-line or even second-line therapy fails, you need to consider doing a diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm or deny the diagnosis.

Dr. Advincula: Are there any points in the evaluation of a patient who visits your practice for the first time where you would immediately offer a surgical approach, as opposed to starting with medical management?

Dr. Hur: A large percentage of my patients undergo surgical evaluation, as surgical diagnosis is the gold standard. If you look at the literature, even among surgeons, the accuracy of visual diagnosis is not great.1,2 I target individuals who are either not responsive to medical treatment or who have never tried medical treatment but are trying to conceive, so they are not medical candidates, or individuals who genuinely want a diagnosis for surgical management—sometimes even before first-line medical treatment.

Dr. Brown: Your examination sometimes also dictates your approach. A patient may never have had a laparoscopy or hormone therapy, but if you find uterosacral ligament nodularity, extreme pain on examination, and suspicious findings on ultrasound or otherwise, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis.

Endometrioma management

Dr. Advincula: Let’s jump ahead. You have decided to proceed with laparoscopy and you encounter an endometrioma. What is your management strategy, particularly in a fertility-desiring patient?

Dr. Hur: Even if a woman has not undergone first-line medical treatment, if she is trying to conceive or presents with infertility, it’s a different balancing act for approaching the patient. When a woman presents, either with an ultrasound finding or an intraoperative finding of an endometrioma, I am a strong advocate of treating symptomatic disease, which means complete cyst excision. Good clinical data suggest that reproductive outcomes are improved for spontaneous pregnancy rates when you excise an endometrioma.3-6

Dr. Advincula: What are the risks of excision of an endometrioma cyst that patients need to know about?

Dr. Brown: Current standard of care is cystectomy, stripping the cyst wall away from the ovarian cortex. There is some concern that the stripping process, depending on how long the endometrioma has been present within the ovary, can cause some destruction to the underlying oocytes and perhaps impact that ovary’s ability to produce viable eggs.

Some studies, from France in particular, have investigated different energy sources, such as plasma energy, that make it possible to remove part of the cyst and then use the plasma energy to vaporize the rest of the cyst wall that may be lying on the cortex. Researchers looked at anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there does seem to be a difference in terms of how you remove the cyst.7-9 This energy source is not available to everyone; it’s similar to laser but does not have as much penetration. Standard of care is still ovarian stripping.

The conversation with the patient—if she is already infertile and this cyst is a problem—would be that it likely needs to be removed. There is a chance that she may need assisted reproduction; she might not be able to get pregnant on her own due either to the presence of the endometrioma or to the surgical process of removing it and stripping.

Dr. Advincula: How soon after surgery can a patient start to pursue trying to get pregnant?

Dr. Hur: I think there is no time restraint outside of recovery. As long as the patient has a routine postoperative course, she can try to conceive, spontaneously or with assisted reproduction. Some data suggest, however, that ovarian reserve is diminished immediately after surgery.10–12 If you look at the spontaneous clinical pregnancy outcomes, they are comparable 3 to 6 months postsurgery.4,12–14

Dr. Brown: I agree. Time is of the essence with a lot of patients, many of whom present after age 35.

Dr. Hur: It’s also important to highlight that there are 2 presentations with endometrioma: the symptomatic patient and the asymptomatic patient. In the asymptomatic patient, her age, reproductive goals, and the bilaterality (whether it is present on both sides or on one side) of the endometrioma are important in deciding on a patient-centered surgical plan. For someone with a smaller cyst, unilateral presentation, and maybe older age at presentation, it may or may not impact assisted reproductive outcomes.

If the patient is not symptomatic and she is older with bilateral endometriomas less than 4 cm, some data suggest that patient might be better served in a conservative fashion.6,15–17 Then, once she is done with assisted reproduction, we might be more aggressive surgically by treating the finding that would not resolve spontaneously without surgical management. It is important to highlight that endometriomas do not resolve on their own; they require surgical management.

Read about managing endometriosis for the patient not seeking fertility

Endometriosis management for the patient not seeking fertility

Dr. Advincula: Let’s now consider a patient on whom you have performed laparoscopy not only to diagnose and confirm the evidence of endometriosis but also to treat endometriosis, an endometrioma, and potentially deeply infiltrative disease. But this person is not trying to get pregnant. Postoperatively, what is your approach?

Dr. Brown: Suppressive therapy for this patient could be first-line or second-line therapy, such as a Lupron Depot or Depo-Provera. We keep the patient on suppressive therapy (whatever treatments work for her), until she’s ready to get pregnant; then we take her off. Hopefully she gets pregnant. After she delivers, we reinitiate suppressive therapy. I will follow these women throughout their reproductive cycle, and I think having a team of physicians who are all on the same page can help this patient manage her disease through her reproductive years.

Dr. Hur: If a patient presented warranting surgical management once, and she is not menopausal, the likelihood that disease will recur is quite high. Understanding the nature and the pathology of the disease, hormonal suppression would be warranted. Suppression is not just for between pregnancies, it’s until the patient reaches natural menopause. It’s also in the hopes of suppressing the disease so she does not need recurrent surgeries.

We typically do not operate unless patients have recurrence of symptoms that no longer respond to medical therapy. Our hope is to buy them more time closer to the age of natural menopause so that medical repercussions do not result in hysterectomy and ovary removal, which have other nongynecologic manifestations, including negative impact on bone and cardiac health.

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: I am a strong advocate of excision of endometriosis. I believe that it's essential to excise for 2 very important reasons. One reason is for diagnosis. Accurately diagnosing endometriosis through visualization alone is poor, even among gynecologic surgeons. It is very important to have an accurate diagnosis of endometriosis, since the diagnosis will then dictate the treatment for the rest of a patient's reproductive life.

The second reason that excision is essential is because you just do not know how much disease there is "behind the scenes." When you start to excise, you begin to appreciate the depth of the disease, and often fibrosis or inflammation is present even behind the endometriosis implant that is visualized.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I approach endometriosis in the same way that an oncologist would approach cancer. I call it cytoreduction--reducing the disease. There is this iceberg phenomenon, where the tip of the iceberg is seen in the water, but you have no idea how deep it actually goes. That is very much deep, infiltrative endometriosis. Performing an ablation on the top does almost nothing for the patient and may actually complicate the situation by causing scar tissue. If a patient has symptoms, I firmly believe that you must resect the disease, whether it is on the peritoneum, bladder, bowel, or near the ureter. Now, these are radical surgeries, and not every patient should have a radical surgery. It is very much based on the patient's pain complaints and issues at that time, but excision of endometriosis really, in my opinion, should be the standard of care.

Risks of excision of endometriosis

Dr. Brown: The risks of disease excision depend on whether a patient has ureteral disease, bladder disease, or bowel disease, suggested through a preoperative or another operative report or imaging. If this is the case, we have a preoperative discussion with the patient about, "To what extent do you want me to go to remove the disease from your pelvis? If I remove it from your peritoneum and your bladder, there is the chance that you'll have to go home with a Foley catheter for a few days. If the bowel is involved, do you want me to try to resect the disease or shave it off the bowel? If we get into a problem, are you okay with me resecting that bowel?" These are the issues that we have to discuss, because there are potential complications, although known.

The role of the LNG-IUD

Dr. Advincula: Something that often comes up is the role of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) as one therapy option, either preoperatively or postoperatively. What is your perspective?

Dr. Hur: I reserve the LNG-IUD as a second-line therapy for patients, predominantly because it allows direct delivery of the medication to the womb (rather than systemic exposure of the medication). For patients who experience adverse effects due to systemic exposure to first-line treatments, it might be a great option. However, I do not believe that it consistently suppresses the ovaries, which we understand feeds the pathology of the hormonal stimulation, and so typically I will reserve it as a second-line treatment.

Dr. Brown: I utilize the LNG-IUD in a similar fashion. I may have patients who have had a diagnostic laparoscopy somewhere else and were referred to me because they now have known stage 3 or 4 endometriosis without endometriomas. Those patients, if they are going to need suppressive therapy after surgery and are not ready to get pregnant, do very well with the LNG-IUD, and I will place it during surgery under anesthesia. If a patient has endometriomas seen at the time of surgery, we could still place an LNG-IUD at the time of surgery. We may need to add on an additional medication, however, like another oral progesterone. I do have patients that use both an IUD and either combined oral contraceptive pills and/or oral progestins. Those patients usually have complicated cases with very deep infiltrative disease.

Read about managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Dr. Advincula: Patients often are quite concerned when the words “endometriosis” and “bowel” come together. How do you manage disease that involves the bowel?

Dr. Hur: A lot of patients with endometriosis have what I call neighboring disease—it’s not limited just to the pelvis, but it involves the neighboring organs including the bowel and bladder. Patients can present with symptoms related to those adjacent organs. However, not all disease involving the bowel or bladder manifests with symptoms, and patients with symptoms may not have visible disease.

Typically, when a patient presents with symptoms of bowel involvement, where the bowel lumen is narrowed to more than 50% and/or she has functional manifestations (signs of obstruction that result in abnormal bowel function), we have serious conversations about a bowel resection. If she has full-thickness disease without significant bowel dysfunction—other than blood in her stool—sometimes we talk about more conservative treatment because of the long-term manifestations that a bowel resection could have.

Dr. Brown: I agree completely. It is important to have a good relationship with our colorectal surgeons. If I suspect that the patient has narrowing of the lumen of the large bowel or she actually has symptoms such as bloody diarrhea during menstruation—which is suggestive of deep, infiltrative and penetrative disease—I will often order a colonoscopy ahead of time to get confirmed biopsies. Then the patient discussion occurs with our colorectal surgeon, who operates with me jointly if we decide to proceed with a bowel resection. It’s important to have subspecialty colleagues involved in this care, because a low anterior resection is a very big surgery and there can be down-the-stream complications.

The importance of multidisciplinary care

Dr. Advincula: What are your perspectives on a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to the patient with endometriosis?

Dr. Brown: As I previously mentioned, it is important to develop a good relationship with colorectal surgery/urology. In addition, behavioral therapists may be involved in the care of patients with endometriosis, for a number of reasons. The disease process is fluid. It will change during the patient’s reproductive years, and you need to manage it accordingly based on her symptoms. Sometimes the diagnosis is not made for 5 to 10 years, and that can lead to other issues: depression, fibromyalgia, or irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient may have multiple issues plus endometriosis. I think having specialists such as gastroenterologists and behavioral therapists on board, as well as colorectal and urological surgeons who can perform these complex surgeries, is very beneficial to the patient. That way, she benefits from the team’s focus and is cared for from start to finish.

Dr. Hur: I like to call the abdomen a studio. It does not have separate compartments for each organ system. It’s one big room, and often the neighboring organs are involved, including the bowel and bladder. I think Dr. Brown’s observation—the multidisciplinary approach to a patient’s comprehensive care—is critical. Like any surgery, preoperative planning and preoperative assessment are essential, and these steps should include the patient. The discussion should cover not only the surgical outcomes that the surgeons expect, but also what the patient expects to be improved. For example, for patients with extensive disease and bowel involvement, a bowel resection is not always the right approach because it can have potential long-term sequelae. Balancing the risks associated with surgery with the long-term benefits is an important part of the discussion.

Dr. Advincula: Those are both excellent perspectives. Endometriosis is a very complicated disease state, does require a multidisciplinary approach to management, and there are implications and strategies that involve both the medical approach to management and the surgical approach.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis is one of the more daunting diagnoses that gynecologists treat. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by

First-time evaluation

Arnold P. Advincula, MD: When a patient presents to your practice for the first time and you suspect endometriosis, what considerations tailor your evaluation, and what does that evaluation involve?

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: The diagnosis is contingent on a patient’s presenting profile. How symptomatic is she? How old is she? What are her reproductive goals? The gold standard for diagnosis is a histologic diagnosis, which is surgical. Depending on the age profile, however, and how close she is to menopause, the patient may be managed medically. Even women in the young reproductive age group may be managed medically if symptoms are responsive to medical treatment.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I agree. When a patient presents without a laparoscopy, or a tissue diagnosis, but the symptoms are consistent with likely endometriosis (depending on where she is in her reproductive cycle and what her goals are), I think treating with a first-line therapy—hormonal treatments such as progestin-only oral contraceptive pills—is acceptable. I usually conduct a treatment trial period of 3 to 6 months to see if she obtains any symptom relief.

If that first-line treatment fails, generally you can move to a second-line treatment.

I have a discussion in which I either offer a second-line treatment, such as medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) or leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot), or get a tissue diagnosis, if possible, by performing laparoscopy. If first-line or even second-line therapy fails, you need to consider doing a diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm or deny the diagnosis.

Dr. Advincula: Are there any points in the evaluation of a patient who visits your practice for the first time where you would immediately offer a surgical approach, as opposed to starting with medical management?

Dr. Hur: A large percentage of my patients undergo surgical evaluation, as surgical diagnosis is the gold standard. If you look at the literature, even among surgeons, the accuracy of visual diagnosis is not great.1,2 I target individuals who are either not responsive to medical treatment or who have never tried medical treatment but are trying to conceive, so they are not medical candidates, or individuals who genuinely want a diagnosis for surgical management—sometimes even before first-line medical treatment.

Dr. Brown: Your examination sometimes also dictates your approach. A patient may never have had a laparoscopy or hormone therapy, but if you find uterosacral ligament nodularity, extreme pain on examination, and suspicious findings on ultrasound or otherwise, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be warranted to confirm the diagnosis.

Endometrioma management

Dr. Advincula: Let’s jump ahead. You have decided to proceed with laparoscopy and you encounter an endometrioma. What is your management strategy, particularly in a fertility-desiring patient?

Dr. Hur: Even if a woman has not undergone first-line medical treatment, if she is trying to conceive or presents with infertility, it’s a different balancing act for approaching the patient. When a woman presents, either with an ultrasound finding or an intraoperative finding of an endometrioma, I am a strong advocate of treating symptomatic disease, which means complete cyst excision. Good clinical data suggest that reproductive outcomes are improved for spontaneous pregnancy rates when you excise an endometrioma.3-6

Dr. Advincula: What are the risks of excision of an endometrioma cyst that patients need to know about?

Dr. Brown: Current standard of care is cystectomy, stripping the cyst wall away from the ovarian cortex. There is some concern that the stripping process, depending on how long the endometrioma has been present within the ovary, can cause some destruction to the underlying oocytes and perhaps impact that ovary’s ability to produce viable eggs.

Some studies, from France in particular, have investigated different energy sources, such as plasma energy, that make it possible to remove part of the cyst and then use the plasma energy to vaporize the rest of the cyst wall that may be lying on the cortex. Researchers looked at anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there does seem to be a difference in terms of how you remove the cyst.7-9 This energy source is not available to everyone; it’s similar to laser but does not have as much penetration. Standard of care is still ovarian stripping.

The conversation with the patient—if she is already infertile and this cyst is a problem—would be that it likely needs to be removed. There is a chance that she may need assisted reproduction; she might not be able to get pregnant on her own due either to the presence of the endometrioma or to the surgical process of removing it and stripping.

Dr. Advincula: How soon after surgery can a patient start to pursue trying to get pregnant?

Dr. Hur: I think there is no time restraint outside of recovery. As long as the patient has a routine postoperative course, she can try to conceive, spontaneously or with assisted reproduction. Some data suggest, however, that ovarian reserve is diminished immediately after surgery.10–12 If you look at the spontaneous clinical pregnancy outcomes, they are comparable 3 to 6 months postsurgery.4,12–14

Dr. Brown: I agree. Time is of the essence with a lot of patients, many of whom present after age 35.

Dr. Hur: It’s also important to highlight that there are 2 presentations with endometrioma: the symptomatic patient and the asymptomatic patient. In the asymptomatic patient, her age, reproductive goals, and the bilaterality (whether it is present on both sides or on one side) of the endometrioma are important in deciding on a patient-centered surgical plan. For someone with a smaller cyst, unilateral presentation, and maybe older age at presentation, it may or may not impact assisted reproductive outcomes.

If the patient is not symptomatic and she is older with bilateral endometriomas less than 4 cm, some data suggest that patient might be better served in a conservative fashion.6,15–17 Then, once she is done with assisted reproduction, we might be more aggressive surgically by treating the finding that would not resolve spontaneously without surgical management. It is important to highlight that endometriomas do not resolve on their own; they require surgical management.

Read about managing endometriosis for the patient not seeking fertility

Endometriosis management for the patient not seeking fertility

Dr. Advincula: Let’s now consider a patient on whom you have performed laparoscopy not only to diagnose and confirm the evidence of endometriosis but also to treat endometriosis, an endometrioma, and potentially deeply infiltrative disease. But this person is not trying to get pregnant. Postoperatively, what is your approach?

Dr. Brown: Suppressive therapy for this patient could be first-line or second-line therapy, such as a Lupron Depot or Depo-Provera. We keep the patient on suppressive therapy (whatever treatments work for her), until she’s ready to get pregnant; then we take her off. Hopefully she gets pregnant. After she delivers, we reinitiate suppressive therapy. I will follow these women throughout their reproductive cycle, and I think having a team of physicians who are all on the same page can help this patient manage her disease through her reproductive years.

Dr. Hur: If a patient presented warranting surgical management once, and she is not menopausal, the likelihood that disease will recur is quite high. Understanding the nature and the pathology of the disease, hormonal suppression would be warranted. Suppression is not just for between pregnancies, it’s until the patient reaches natural menopause. It’s also in the hopes of suppressing the disease so she does not need recurrent surgeries.

We typically do not operate unless patients have recurrence of symptoms that no longer respond to medical therapy. Our hope is to buy them more time closer to the age of natural menopause so that medical repercussions do not result in hysterectomy and ovary removal, which have other nongynecologic manifestations, including negative impact on bone and cardiac health.

Hye-Chun Hur, MD, MPH: I am a strong advocate of excision of endometriosis. I believe that it's essential to excise for 2 very important reasons. One reason is for diagnosis. Accurately diagnosing endometriosis through visualization alone is poor, even among gynecologic surgeons. It is very important to have an accurate diagnosis of endometriosis, since the diagnosis will then dictate the treatment for the rest of a patient's reproductive life.

The second reason that excision is essential is because you just do not know how much disease there is "behind the scenes." When you start to excise, you begin to appreciate the depth of the disease, and often fibrosis or inflammation is present even behind the endometriosis implant that is visualized.

Douglas N. Brown, MD: I approach endometriosis in the same way that an oncologist would approach cancer. I call it cytoreduction--reducing the disease. There is this iceberg phenomenon, where the tip of the iceberg is seen in the water, but you have no idea how deep it actually goes. That is very much deep, infiltrative endometriosis. Performing an ablation on the top does almost nothing for the patient and may actually complicate the situation by causing scar tissue. If a patient has symptoms, I firmly believe that you must resect the disease, whether it is on the peritoneum, bladder, bowel, or near the ureter. Now, these are radical surgeries, and not every patient should have a radical surgery. It is very much based on the patient's pain complaints and issues at that time, but excision of endometriosis really, in my opinion, should be the standard of care.

Risks of excision of endometriosis

Dr. Brown: The risks of disease excision depend on whether a patient has ureteral disease, bladder disease, or bowel disease, suggested through a preoperative or another operative report or imaging. If this is the case, we have a preoperative discussion with the patient about, "To what extent do you want me to go to remove the disease from your pelvis? If I remove it from your peritoneum and your bladder, there is the chance that you'll have to go home with a Foley catheter for a few days. If the bowel is involved, do you want me to try to resect the disease or shave it off the bowel? If we get into a problem, are you okay with me resecting that bowel?" These are the issues that we have to discuss, because there are potential complications, although known.

The role of the LNG-IUD

Dr. Advincula: Something that often comes up is the role of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) as one therapy option, either preoperatively or postoperatively. What is your perspective?

Dr. Hur: I reserve the LNG-IUD as a second-line therapy for patients, predominantly because it allows direct delivery of the medication to the womb (rather than systemic exposure of the medication). For patients who experience adverse effects due to systemic exposure to first-line treatments, it might be a great option. However, I do not believe that it consistently suppresses the ovaries, which we understand feeds the pathology of the hormonal stimulation, and so typically I will reserve it as a second-line treatment.

Dr. Brown: I utilize the LNG-IUD in a similar fashion. I may have patients who have had a diagnostic laparoscopy somewhere else and were referred to me because they now have known stage 3 or 4 endometriosis without endometriomas. Those patients, if they are going to need suppressive therapy after surgery and are not ready to get pregnant, do very well with the LNG-IUD, and I will place it during surgery under anesthesia. If a patient has endometriomas seen at the time of surgery, we could still place an LNG-IUD at the time of surgery. We may need to add on an additional medication, however, like another oral progesterone. I do have patients that use both an IUD and either combined oral contraceptive pills and/or oral progestins. Those patients usually have complicated cases with very deep infiltrative disease.

Read about managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Managing endometriosis involving the bowel

Dr. Advincula: Patients often are quite concerned when the words “endometriosis” and “bowel” come together. How do you manage disease that involves the bowel?

Dr. Hur: A lot of patients with endometriosis have what I call neighboring disease—it’s not limited just to the pelvis, but it involves the neighboring organs including the bowel and bladder. Patients can present with symptoms related to those adjacent organs. However, not all disease involving the bowel or bladder manifests with symptoms, and patients with symptoms may not have visible disease.

Typically, when a patient presents with symptoms of bowel involvement, where the bowel lumen is narrowed to more than 50% and/or she has functional manifestations (signs of obstruction that result in abnormal bowel function), we have serious conversations about a bowel resection. If she has full-thickness disease without significant bowel dysfunction—other than blood in her stool—sometimes we talk about more conservative treatment because of the long-term manifestations that a bowel resection could have.

Dr. Brown: I agree completely. It is important to have a good relationship with our colorectal surgeons. If I suspect that the patient has narrowing of the lumen of the large bowel or she actually has symptoms such as bloody diarrhea during menstruation—which is suggestive of deep, infiltrative and penetrative disease—I will often order a colonoscopy ahead of time to get confirmed biopsies. Then the patient discussion occurs with our colorectal surgeon, who operates with me jointly if we decide to proceed with a bowel resection. It’s important to have subspecialty colleagues involved in this care, because a low anterior resection is a very big surgery and there can be down-the-stream complications.

The importance of multidisciplinary care

Dr. Advincula: What are your perspectives on a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to the patient with endometriosis?

Dr. Brown: As I previously mentioned, it is important to develop a good relationship with colorectal surgery/urology. In addition, behavioral therapists may be involved in the care of patients with endometriosis, for a number of reasons. The disease process is fluid. It will change during the patient’s reproductive years, and you need to manage it accordingly based on her symptoms. Sometimes the diagnosis is not made for 5 to 10 years, and that can lead to other issues: depression, fibromyalgia, or irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient may have multiple issues plus endometriosis. I think having specialists such as gastroenterologists and behavioral therapists on board, as well as colorectal and urological surgeons who can perform these complex surgeries, is very beneficial to the patient. That way, she benefits from the team’s focus and is cared for from start to finish.

Dr. Hur: I like to call the abdomen a studio. It does not have separate compartments for each organ system. It’s one big room, and often the neighboring organs are involved, including the bowel and bladder. I think Dr. Brown’s observation—the multidisciplinary approach to a patient’s comprehensive care—is critical. Like any surgery, preoperative planning and preoperative assessment are essential, and these steps should include the patient. The discussion should cover not only the surgical outcomes that the surgeons expect, but also what the patient expects to be improved. For example, for patients with extensive disease and bowel involvement, a bowel resection is not always the right approach because it can have potential long-term sequelae. Balancing the risks associated with surgery with the long-term benefits is an important part of the discussion.

Dr. Advincula: Those are both excellent perspectives. Endometriosis is a very complicated disease state, does require a multidisciplinary approach to management, and there are implications and strategies that involve both the medical approach to management and the surgical approach.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2004;111(11):1204–1212.

- Fernando S, Soh PQ, Cooper M, et al. Reliability of visual diagnosis of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):783–789.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1176–1180.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004992.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

- Stochino-Loi E, Darwish B, Mircea O, et al. Does preoperative antimüllerian hormone level influence postoperative pregnancy rate in women undergoing surgery for severe endometriosis? Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):707–713.e3.

- Motte I, Roman H, Clavier B, et al. In vitro fertilization outcomes after ablation of endometriomas using plasma energy: A retrospective case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2016;44(10):541–547.

- Roman H, Bubenheim M, Auber M, Marpeau L, Puscasiu L. Antimullerian hormone level and endometrioma ablation using plasma energy. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

- Saito N, Okuda K, Yuguchi H, Yamashita Y, Terai Y, Ohmichi M. Compared with cystectomy, is ovarian vaporization of endometriotic cysts truly more effective in maintaining ovarian reserve? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):804–810.

- Giampaolino P, Bifulco G, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mercorio A, Bruzzese D, Di Carlo C. Endometrioma size is a relevant factor in selection of the most appropriate surgical technique: a prospective randomized preliminary study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;195:88–93.

- Chang HJ, Han SH, Lee JR, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: serial changes of serum anti-MTimes New Romanüllerian hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):343–349.

- Ding Y, Yuan Y, Ding J, Chen Y, Zhang X, Hua K. Comprehensive assessment of the impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(7):1252–1259.

- Mircea O, Puscasiu L, Resch B, et al. Fertility outcomes after ablation using plasma energy versus cystectomy in infertile women with ovarian endometrioma: A multicentric comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(7):1138–1145.

- Ozaki R, Kumakiri J, Tinelli A, Grimbizis GF, Kitade M, Takeda S. Evaluation of factors predicting diminished ovarian reserve before and after laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas: a prospective cohort study. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9(1):37.

- Demirol A, Guven S, Baykal C, Gurgan T. Effect of endometrioma cystectomy on IVF outcome: A prospective randomized study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12(5):639–643.

- Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, et al; ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704.

- Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2004;111(11):1204–1212.

- Fernando S, Soh PQ, Cooper M, et al. Reliability of visual diagnosis of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):783–789.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1176–1180.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004992.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

- Stochino-Loi E, Darwish B, Mircea O, et al. Does preoperative antimüllerian hormone level influence postoperative pregnancy rate in women undergoing surgery for severe endometriosis? Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):707–713.e3.

- Motte I, Roman H, Clavier B, et al. In vitro fertilization outcomes after ablation of endometriomas using plasma energy: A retrospective case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2016;44(10):541–547.

- Roman H, Bubenheim M, Auber M, Marpeau L, Puscasiu L. Antimullerian hormone level and endometrioma ablation using plasma energy. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

- Saito N, Okuda K, Yuguchi H, Yamashita Y, Terai Y, Ohmichi M. Compared with cystectomy, is ovarian vaporization of endometriotic cysts truly more effective in maintaining ovarian reserve? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):804–810.

- Giampaolino P, Bifulco G, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mercorio A, Bruzzese D, Di Carlo C. Endometrioma size is a relevant factor in selection of the most appropriate surgical technique: a prospective randomized preliminary study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;195:88–93.

- Chang HJ, Han SH, Lee JR, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: serial changes of serum anti-MTimes New Romanüllerian hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):343–349.

- Ding Y, Yuan Y, Ding J, Chen Y, Zhang X, Hua K. Comprehensive assessment of the impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(7):1252–1259.

- Mircea O, Puscasiu L, Resch B, et al. Fertility outcomes after ablation using plasma energy versus cystectomy in infertile women with ovarian endometrioma: A multicentric comparative study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(7):1138–1145.

- Ozaki R, Kumakiri J, Tinelli A, Grimbizis GF, Kitade M, Takeda S. Evaluation of factors predicting diminished ovarian reserve before and after laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas: a prospective cohort study. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9(1):37.

- Demirol A, Guven S, Baykal C, Gurgan T. Effect of endometrioma cystectomy on IVF outcome: A prospective randomized study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12(5):639–643.

- Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, et al; ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704.

Take-home points

- Endometriosis management involves fluidity of care. Treatment approaches will change throughout a patient's reproductive life, depending on the patient's presenting symptoms and reproductive goals.

- Inform the patient of the disease process and how it may affect her menstrual pain symptoms and family planning.

- Educate patients so they may effectively participate in the management discussion. Hear the voice of the patient to make a tailored plan of care for each individual.

- Endometriosis can be a complex medical problem. Use a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach when appropriate.

Watch: Video roundtable–Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Video roundtable–Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Your patient has a large symptomatic fibroid: Tools for decision making

2017 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

Gynecologic surgeons who trained in the early 1990s may feel that the practice of gynecologic surgery seemed simpler back then. There were really only 2 ways to perform a hysterectomy: vaginally (TVH—total vaginal hysterectomy) and abdominally (TAH—total abdominal hysterectomy). Global endometrial ablation devices were not an established treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding, and therapeutic advancements such as hormonally laden intrauterine devices, vaginal mesh kits, and surgical robots did not exist. The options in the surgical toolbox were limited, and the general expectation in residency was long hours. During that period, consistent exposure to the operating room and case volume allowed one to graduate confidant in one’s surgical skills.

The changing landscape of gynecologic surgery

Fast-forward to 2017. Now, so many variables affect the ability to produce a well-trained gynecologic surgeon. In fact, in 2015 Guntupalli and colleagues studied the preparedness of ObGyn residents for fellowship training in the 4 subspecialties of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, gynecologic oncology, maternal-fetal medicine, and reproductive endocrinology-infertility.1 Through a validated survey of fellowship program directors, the authors found that only 20% of first-year fellows were able to perform a vaginal hysterectomy independently, and 46%, an abdominal hysterectomy. Barely 50% of first-year fellows in all subspecialties studied could independently set up a retractor for laparotomy and appropriately pack and mobilize the bowel for pelvic surgery.1

Today the hysterectomy procedure has become the proverbial alphabet soup. Trainees are confronted with having to learn not only the TVH and the TAH but also the LAVH (laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy), LSH (laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy), TLH (total laparoscopic hysterectomy), and RALH (robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy).2 With a mandated 80-hour residency workweek restriction and an increasing number of minimally invasive hysterectomies performed nationally, a perfect storm exists for critically evaluating the current paradigm of resident and fellow surgical training.3

One may wonder if current controversies surrounding many of the technologic advancements in gynecologic surgery result from inadequate training and too many treatment options or from flaws in the actual devices. A “see one, do one, teach one” approach to assimilating surgical skills is no longer an accepted approach, and although the “10,000-hour rule” of focused practice to attain expertise makes sense, how can a trainee gain enough exposure to achieve competency?

Related article:

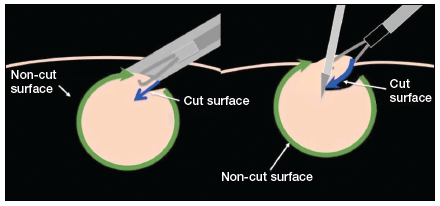

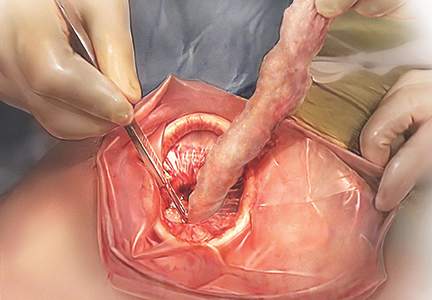

The Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique

Simulation: A creditable training tactic

This is where simulation—whether low or high fidelity—potentially can fill in some of those training gaps. Simulation in medicine is a proven instructional design strategy in which learning is an active and experiential process. Studies clearly have shown that simulation-based medical education (SBME) with deliberate practice is superior to traditional clinical medical education in achieving specific clinical skill acquisition goals.4

This special Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery offers a 30,000-foot overview of the current state of simulation in gynecologic surgical training. Equally important to this conversation is the process by which a trained individual can obtain the appropriate credentials and subsequent privileging to perform various surgical procedures. Simulation has begun to play a significant role not only in an individual’s initial credentialing and privileging in surgery but also in maintaining those privileges.

Read about the evolving role of simulation in gyn surgery training.

Simulation's evolving role in gyn surgery training

Recently, the traditional model of gynecologic surgical training has been impacted by the exponential growth of technology (surgical devices), increased surgical options, and the limited work hours of trainees. As a result, simulation-based medical education has been identified as a potential solution to address deficits in surgical training. Fortunately, all modalities of surgery are now amenable to improvements in surgical education via simulation.5

Although basic skill training in the standard areas of hand-eye coordination, tissue handling, and instrument use still is prerequisite, the integration of both low- and high-fidelity simulation technologies--with enhanced functionality--now allows for a more comprehensive approach to understanding surgical anatomy. In addition, simulation training provides the opportunity for independent practice of full surgical procedures and, in many instances, offers objective and instantaneous assessment feedback for the learner. This discussion highlights some of the relevant literature on simulation training and the impact of surgical simulation on hysteroscopy and laparoscopy.

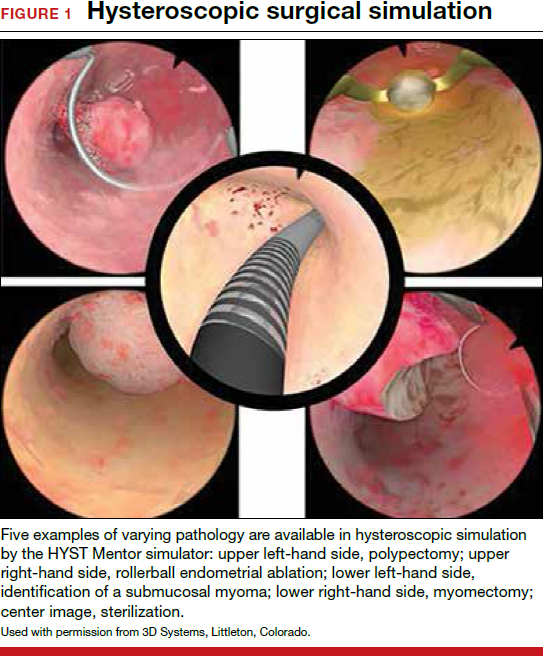

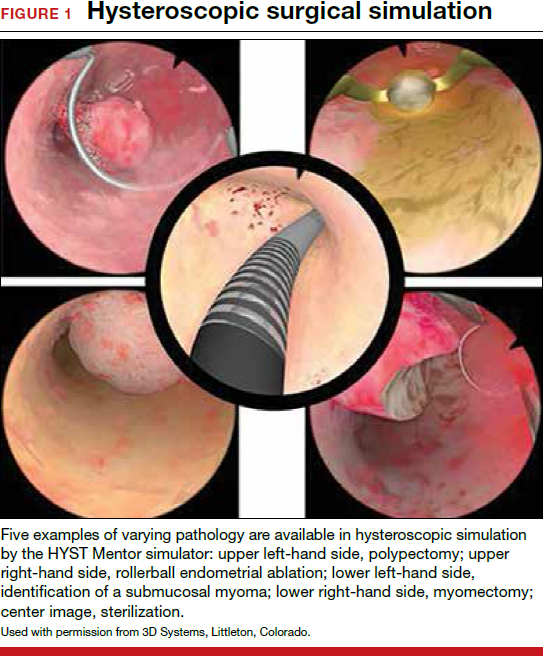

Box trainers and virtual reality simulators in hysteroscopy training

Hysteroscopic surgery allows direct endoscopic visualization of the uterine cavity for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. While the majority of these procedures are generally low risk, operative hysteroscopic experience minimizes the possibility of significant procedure-related complications, such as uterine perforation.5 The literature repeatedly shows that significant differences exist in skill and sense of preparedness between the novice or inexperienced surgeon (resident trainee) and the expert in hysteroscopic surgery.6-8

Both low- and high-fidelity hysteroscopic simulators can be used to fine-tune operator skills. Low-fidelity simulators such as box trainers, which focus on skills like endometrial ablation and hysteroscopic resection with energy, have been shown to measurably improve performance, and they are well-received by participants. Low-fidelity simulations that incorporate vegetable/fruit or animal models (for example, porcine bladders and cattle uteri) have also been employed with success.9

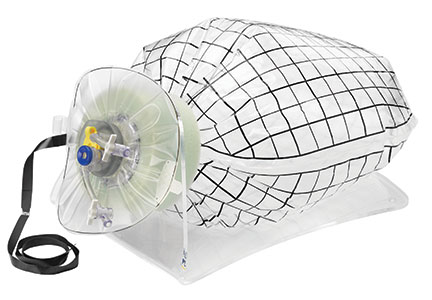

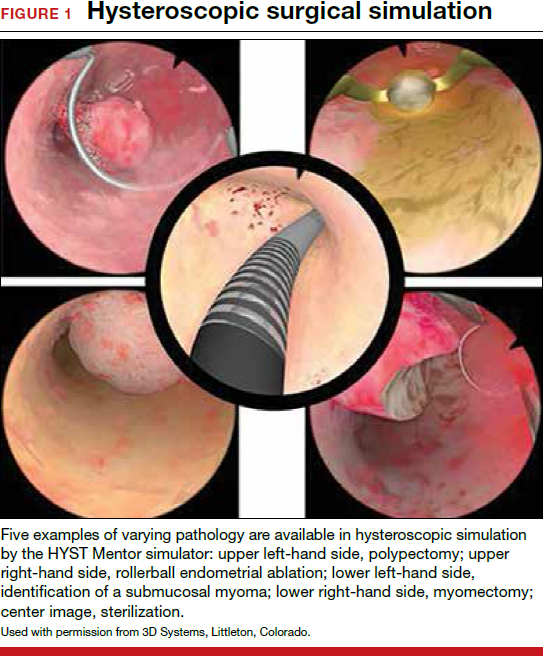

On the high-fidelity end, surgical trainees can now experience hysteroscopic surgery simulation through virtual reality simulators, which have evolved with improvements in technology (FIGURE 1). Many high-fidelity simulators have been developed, and technical skill and theoretical knowledge improve with their use. Overall, trainees have provided positive feedback regarding the realism and training capacity afforded by virtual reality simultors.10,11

Various simulators are equipped with complete training curriculums that focus on essential surgical skills. Common troubleshooting techniques taught via simulator include establishing and maintaining clear views, detecting and coagulating bleeding sources, fluid management and handling, and instrument failure. Learners can perform these sessions repeatedly, independent of their respective starting skill level. On completion of simulation training, the trainee is given objective performance assessments on economy of motion, visualization, safety, fluid handling, and other skills.

Related article:

ExCITE: Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple with simulation

Learning the complexities of laparoscopy through simulation

Laparoscopic surgery (both conventional and robot assisted) allows for a minimally invasive, cost-effective, and rapid-recovery approach to the management of many common gynecologic conditions. In both approaches, the learning curve to reach competency is steep. Conventional laparoscopy requires unique surgical skills, including adapting to a 2-dimensional field with altered depth perception; this creates challenges in spatial reasoning and achieving proficiency in video-eye-hand coordination as a result of the fulcrum effect inherent in laparoscopic instrumentation. This is further complicated by the essential dexterity required to complete dissections and suturing.12,13

Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery requires significant modifications to adapt to a 3-dimensional view. In addition, this approach incorporates another level of complexity (and challenge to attaining mastery), namely, using remotely controlled multiple instrument arms with no tactile feedback.

Importantly, some residency training programs are structured unevenly, emphasizing one or the other surgical modality.14 As a result, this propagates certain skills--or lack thereof--on graduation, and thus highlights potential areas of laparoscopic training that need to be improved and enhanced.

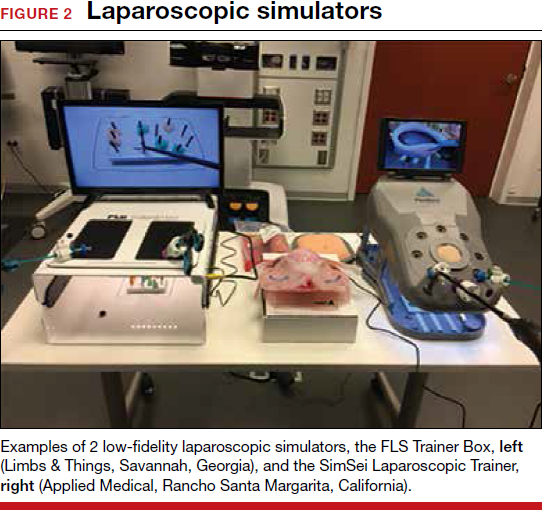

Increasing the learning potential

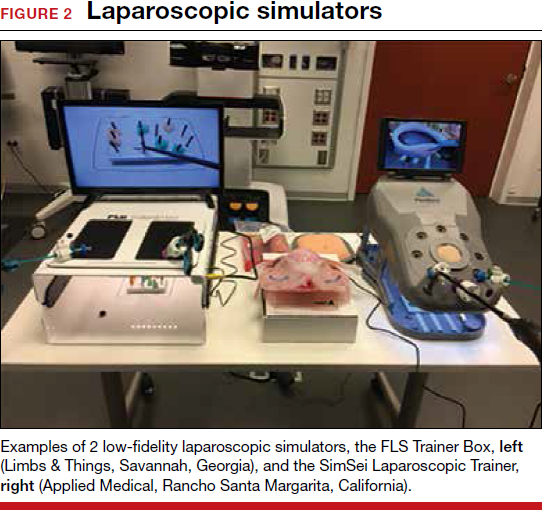

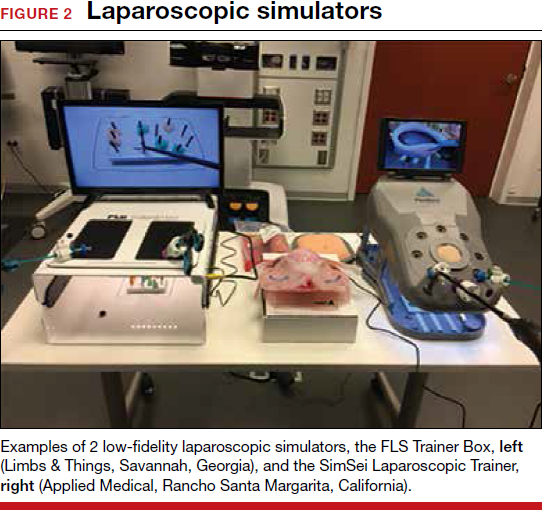

The growing integration of low- and high-fidelity simulation training in laparoscopic surgery has led to improved skill acquisition.12,13,15,16 A well-established low-fidelity simulation model is the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery module, through which trainees are taught vital psychomotor skills via a validated box trainer that is also supported by a cognitive component (FIGURE 2).17,18

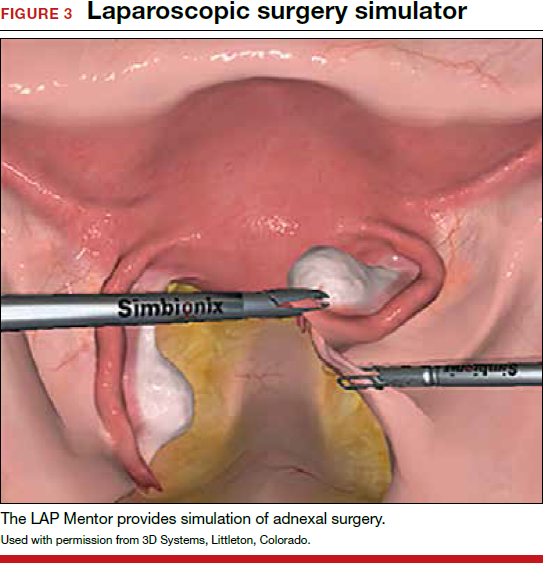

The advent of laparoscopic virtual reality training systems has raised the learning potential further, even for experienced surgeons. Some benefits of virtual reality simulation in conventional laparoscopy include education on an interactive 3D pelvis, step-by-step procedural guidance, a comprehensive return of performance metrics on vital laparoscopic skills, and the incorporation of advanced skills such as laparoscopic suturing, complex dissections, and lysis of adhesions.

In the arena of robot-assisted procedures, simulation modules are available for learning fundamental skill development in hand-eye coordination, depth perception, bimanual manipulation, camera navigation, and wrist articulation.

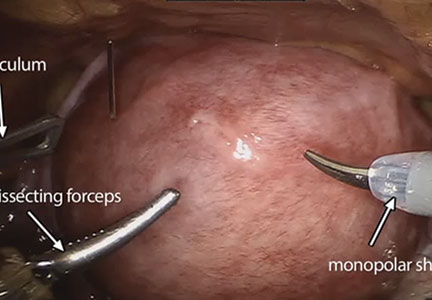

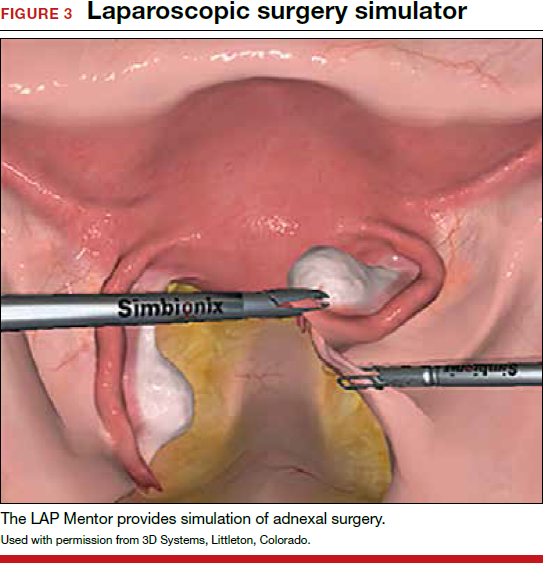

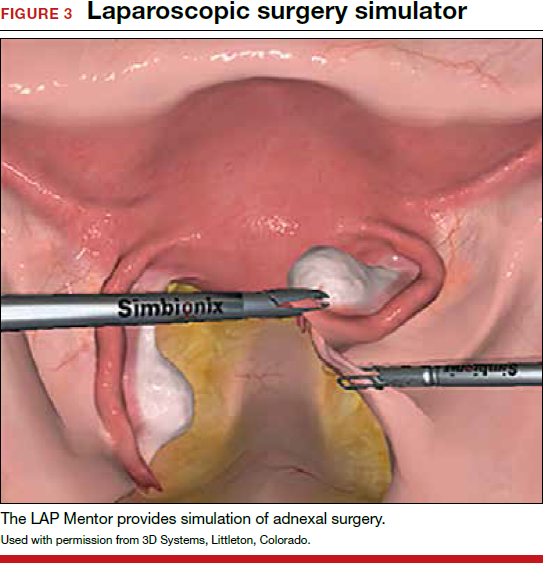

In both conventional and robot-assisted laparoscopy simulation pathways, complete procedural curriculums (for example, hysterectomy with adnexectomy) are available. Thus, learners can start a procedure or technique at a point applicable to them, practice repeatedly until competency, and eventually become proficient (FIGURE 3).

Generally, high-fidelity computerized simulators provide a comprehensive performance report on completion of training, along with a complete recording of the trainee's encounter during accruement of skill. Most importantly, laparoscopic training via simulation has been validated to translate into improved operating room performance by impacting operating times, safety profiles, and surgical skill growth.15,19

Related article:

Complete colpectomy & colpocleisis: Model for simulation

Simulation is a mainstream training tool

The skills gap between expert surgeons and new trainees continues to widen. A comprehensive educational pathway that provides an optimistic safety profile, abides by time constraints, and elevates skill sets will fall to simulation-based surgical training.20,21 Surgical competence is defined not simply by observation and Halstedian technique but by a combination of cognitive and behavioral abilities as well as perceptual and psychomotor skills. It is impractical to expect current learners to become proficient in visuospatial and tactile perception and to demonstrate technical competency without supplementing their training.22-24 Ultimately, as experience with both low- and high-fidelity surgical simulation grows, the predictive validity of this type of training pathway will become more readily apparent. In other words, improved performance in the simulated environment will translate into improved performance in the operating room.

Read about how gyn surgery simulation is being incorporated into credentialing and privileging

Incorporating gyn surgery simulation into credentialing and privileging

Over the last 25 years surgeons have seen unprecedented changes in technology that have revolutionized our surgical approaches to common gynecologic conditions. In the past, granting surgical privileges was pretty straightforward. Surgeons were granted privileges based on successfully completing their training, and subsequent renewal of those privileges was based on not having any significant misadventures or complications. With the advent of laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, and then robot-assisted surgery, training surgeons and verifying their competency has become much more complicated. The variety of surgical approaches now being taught coupled with reduced resident training time and decreasing case volumes have significantly impacted the traditional methodologies of surgical training.25,26

Related article:

How the AAGL is trying to improve outcomes for patients undergoing robot-assisted gynecologic surgery

High-tech surgery demands high-tech training

The development of high-tech surgical approaches has been accompanied by the natural development of simulation models to help with training. Initially, inanimate models, animal labs, and cadavers were used. Over the last 15 years, several innovative companies have developed virtual reality simulation platforms for laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, and even robotics.27 These virtual reality simulators allow students to develop the psychomotor skills necessary to perform minimally invasive procedures and to practice those skills until they can demonstrate proficiency before operating on a live patient.

Most would agree that the key to learning a surgical skill is to "practice, practice, practice."28 Many studies have shown that improvement in surgical outcomes is clearly related to a surgeon's case volume.29,30 But with case volumes decreased, simulation has evolved as the best training alternative. Current surgical simulators enable a student to engage in "deliberate practice"; that is, to have tasks with well-defined goals, to be motivated to improve, and to receive immediate feedback along with opportunities for repetition and refinements of performance.

Simulation allows students to try different surgical techniques and to use "deliberate practice" avoidance of errors in a controlled, safe situation that provides immediate performance feedback.31 Currently, virtual reality simulators are available for hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and robot-assisted gynecologic applications. Early models focused solely on developing a learner's psychomotor skills necessary to safely perform minimally invasive surgeries. Newer simulators add a cognitive component to help students learn specific procedures, such as adnexectomy and hysterectomy.32

Based on the aviation simulator training model, the AAGL endorsed a Gynecologic Robotic Surgery Credentialing and Privileging Guideline in 2014; this guidance relies heavily on simulation for initial training as well as for subsequent annual recertification.33 Many institutions, including the MultiCare Health System in Tacoma, Washington, require all surgeons--even high-volume surgeons--to demonstrate proficiency annually by passing required robotic simulation exercises at least 2 times consecutively in order to maintain robotic surgery privileges.34

A work-around for a simulation drawback

Using simulation for recertification has been criticized because, although it can confirm that a surgeon is skilled enough to operate the tool, it does not evaluate surgical judgment or technique. In response, crowdsourced review of an individual surgeon's surgical videos has proven to be a useful, dependable way to give a surgeon direct feedback regarding his or her performance on a live patient.35 Many institutions now use this technology not only for initial training but also for helping surgeons improve with direct feedback from master surgeon reviewers. Other institutions have considered replacing annual re-credentialing case volume requirements with this technology, which actually assesses competence in a more accurate way.36

Related article:

Flight plan for robotic surgery credentialing: New AAGL guidelines

A new flight plan

The bottom line is that the training and annual recertification of future surgeons now mimics closely the pathway that all airplane pilots are required to follow.

Initial training will require mastery of surgical techniques using a simulator before taking a "solo flight" on a live patient.

Maintenance of privileges now requires either large case volumes or skills testing on a simulator. Many institutions now also require an annual "check ride," such as a crowdsourced video review of a surgeon's cases, as described above.