User login

Top 10 tips community hospitalists need to know for implementing a QI project

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Consider low-cost, high-impact projects

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

Quality improvement (QI) is essential to the advancement of medicine. QI differs from research as it focuses on already proven knowledge and aims to make quick, sustainable change in local health care systems. Community hospitals may not have organized quality improvement initiatives and often rely on individual hospitalists to be their champions.

Although there are resources for quality improvement projects, initiating a project can seem daunting to a hospitalist. Our aim is to equip the community hospitalist with basic skills to initiate their own successful project. We present our “Top 10” tips to review.

1. Start small: Many quality improvement ideas include grandiose changes that require a large buy-in or worse, more money. When starting a QI project, you need to consider low-cost, high-impact projects. Even the smallest projects can make considerable change. Focus on ideas that require only one or two improvement cycles to implement. Understand your hospital culture, flow, and processes, and then pick a project that is reasonable.

Projects can be as simple as decreasing the number of daily labs ordered by your hospitalist group. Projects that are small could still improve patient satisfaction and decrease costs. Listen to your colleagues, if they are discussing an issue, turn this into an idea! As you learn the culture of your hospital you will be able to tackle larger projects. Plus, it gets your name out there!

2. Establish buy-in: Surround yourself with champions of your cause. Properly identifying and engaging key players is paramount to a successful QI project. First, start with your hospital administration, and garner their support by aligning your project with the goals and objectives that the administration leaders have identified to be important for your institution. Next, select a motivated multidisciplinary team. When choosing your team, be sure to include a representative from the various stakeholders, that is, the individuals who have a variety of hospital roles likely to be affected by the outcome of the project. Stakeholders ensure the success of the project because they have a fundamental understanding of how the project will influence workflow, can predict issues before they arise, and often become empowered to make changes that directly influence their work.

Lastly, include at least one well-respected and highly influential member on your team. Change is always hard, and this person’s support and endorsement of the project, can often move mountains when challenges arise.

3. Know the data collector: It is important to understand what data can be collected because, without data, you cannot measure your success. Arrange a meeting and develop a partnership with the data collector. Obtain a general understanding of how and what specific data is collected. Be sure the data collector has a clear understanding of the project design and the specific details of the project. Include the overall project mission, specific aims of the project, the time frame in which data should be collected, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Often, data collectors prefer to collect extra data points upfront, even if you end up not using some of them, rather than having to find missing data after the fact. Communication is key, so be available for questions and open to the suggestions of the data collector.

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel: Prior to starting any QI projects, evaluate available resources for project ideas and implementation. The Society of Hospital Medicine and the American College of Physicians outline multiple projects on their websites. Reach out to colleagues at other institutions and obtain their input as they are likely struggling with similar issues and/or have worked on similar project ideas. Use these resources as scaffolding and edit them to fit your institution’s processes and culture, and use their metrics as your measures of success.

5. Remove waste: When determining QI projects, consider focusing on health care waste. Many of the current processes at our institutions have redundancies that add unhealthy time, effort, and inefficiency to our days that can not only impede patient care but also can lead to burnout. When outlining a project idea, consider mapping the process in your interested area to identify those redundancies and inefficiencies. Consider focusing on these instead of building an entirely new process. Improving inefficiencies also can help with provider buy-in with process changes, especially if this helps in improving their everyday frustrations.

6. Express your values: Create a sense of urgency around the problem you are trying to solve. Educate your colleagues to understand the depth of the QI initiative and its impact on their ability to care for patients and patient safety. Express genuine interest in improving your colleagues’ ability to care for patients and improve their days.

Sharing your passion about your project allows people to understand your vested interest in improving the system. This will inspire team members to lead the way to change and encourage colleagues to adopt the recommended changes.

7. Recognize and reward your team: Involve “champions” in every process change. Identify people who are part of your team and ensure they feel valued. Recognition and acknowledgment will allow people to feel more involved and to gain their buy-in. When it comes to results or progress, consider your group’s dynamics. If they are competitive, consider posting progress results on a publicly displayed run chart. If your group is less likely to be motivated by competition, hold individual meetings to help show progress. This is a crucial dynamic to understand, because creating a competitive environment may alienate some members of your group. Remember, the final result is not to blame those lagging behind but to encourage everyone to find the best pathway to success.

8. Be okay with failure: Celebrate your failures because failure is a chance to learn. Every failure is an educational opportunity to understand what not to do, or a chance to gain insight into a process that did not work.

Be a divergent thinker. Start considering problems as part of the path to solution, rather than a barrier in the way. Be open to change and learn from your mistakes. Don’t just be okay with your failures, own them. This will lead to trust with your team members and show your commitment.

9. Finish: This is key. You must finish your project. Even if you anticipate that the project will fail, you should see the project through to its completion. This proves both you and the process of QI are valid and worthwhile; you have to see results and share them with others.

Completing your project also shows your colleagues that you are resilient, committed, and dedicated. Completing a QI project, even with disappointing results, is a success in and of itself. In the end, it is most important to remember to show progress, not perfection.

10. Create sustainability: When your QI project is finished, you need to decide if the changes are sustainable. Some projects show small change and do not need permanent implementation, rather reminders over time. Other projects may be sustainable with EHR or organizational changes. Once you have successful results, your goal should be to find a way to ensure that the process stays in place over time. This is where all your hard work establishing buy-in comes in handy. Your team is more likely to create sustainable change with the hard work you forged through following these key tips.

These Top 10 tips are a hospitalist’s starting point to begin making changes at their own community hospital. Your motivation and effort in making quality change will not go unnoticed. Small ideas will open doors for larger, more sustainable QI projects. Remember, a failure just means a new idea for the next cycle! Enjoy the process of working collaboratively with your hospital on improving quality. Good luck!

Dr. Astik is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago. Dr. Corbett is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, Tulsa. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Ronan is a hospitalist and associate professor at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, Santa Fe, NM.

When should nutritional support be implemented in a hospitalized patient?

Case

A 60-year-old male with a history of head & neck cancer, treated with radical neck dissection and radiation 5 years prior is admitted with community-acquired pneumonia and anasarca. Prior to admission, he was on a soft dysphagia diet and reports increased difficulty with solid foods and weight loss from 70 kg to 55 kg over 2.5 years. Should nutritional support be initiated?

Background

Malnutrition is associated with increased hospital mortality, decreased functional status and quality of life, infections, longer length of stay, higher hospital costs, and more frequent nonelective readmissions.1,2

Identifying patients who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition

An international consensus committee recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of undernutrition if two of six are present3:

- Insufficient energy intake.

- Weight loss.

- Loss of muscle mass.

- Loss of subcutaneous fat.

- Localized or generalized fluid accumulation that may sometimes mask weight loss.

- Diminished functional status as measured by handgrip strength.

The joint commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours. The American College of Gastroenterologists recommends using a validated score to assess nutritional risk, such as the Nutritional Risk Score (NRS) 2002 or the NUTRIC (Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill) Score, which use a combination of nutritional status and diet-related factors – weight loss, body mass index, and food intake – and also severity of illness measurements.4

- Starvation-related malnutrition, such as anorexia nervosa, presents with a deficiency in calories and protein without inflammation, .

- Chronic disease–related malnutrition, such as that caused chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and obesity, presents with mild to moderate inflammation.

- Acute disease or injury–related malnutrition, such as that caused by sepsis, burns, and trauma, presents with acute and severe inflammation.

Laboratory indicators such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Instead, as negative acute-phase reactants, they can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation.4

Overview of the data

What are the indications for initiating nutritional support, and what is the optimal timing for initiation?

Patients who are malnourished or at significant risk for becoming malnourished should receive specialized nutrition support. Early enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of admission in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk who are unable to maintain volitional intake.6 In the absence of preexisting malnutrition, nutritional support should be provided for patients with inadequate oral intake for 7-14 days or for those in whom inadequate oral intake is expected over the same time period.7

How should nutritional support be administered?

Dietary modification and supplementation

In patients who can tolerate an oral diet, dietary modifications may be made in order to facilitate the provision of essential nutrients in a well-tolerated form. Modifications may include adjusting the consistency of foods, energy value of foods, types of nutrients consumed, and number and frequency of meals.8 Commercial meal replacement beverages are widely used to support a standard oral diet, but there is no data to support their routine use.7

Enteral nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) is the method of choice for administering nutrition support. Contraindications to enteral feeding include diffuse peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and gastrointestinal ischemia.9 The potential advantages of EN over parenteral nutrition (PN) include decreased infection rate, decreased total complications, and shorter length of stay, but there has been no observed difference in mortality. EN is also suggested to have nonnutritional benefits related to providing luminal nutrients – these include maintaining gut integrity, beneficial immune responses, and favorable metabolic responses that help maintain euglycemia and enhance more physiologic fuel utilization.4

Enteral feeding can be administered through the following routes of access:

- Nasogastric tubes: A nasogastric or orogastric tube with radiologic confirmation of positioning is the first line of enteral access. Gastric feeding is preferred because it is well tolerated in the majority of patients, is more physiological, requires a lower level of expertise, and minimizes any delay in initiation of feeding.

- Postpyloric tubes: Postpyloric feeding tubes are indicated if gastric feeding is poorly tolerated or if the patient is at high risk for aspiration because jejunal feedings decrease the incidence of reflux, regurgitation, and aspiration.

- Percutaneous access: When long-term enteral access is required – that is, for greater than 4 weeks – a percutaneous enteral access device should be placed. Prolonged use of a nasoenteric tube may be associated with erosion of the nares and an increase in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia, sinusitis, and esophageal ulceration or stricture. Patients who have had a stroke are the most likely to benefit from percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement, as 40% of patients can have continued dysphagia as long as 1 year after.4,10 Absolute contraindications for PEG placement include serious coagulation disorders (international normalized ratio greater than 1.5; fewer than 50,000 platelets/mcL), sepsis, abdominal wall infections, marked peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritonitis, severe gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or a history of total gastrectomy. Risks often outweigh benefits in patients who have cirrhosis with ascites, patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, and patients who have portal hypertension with gastric varices, but PEG can be considered on a case-by-case basis.11

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition is reserved for patients in whom enteral feeding is contraindicated or who fail to meet their nutritional needs with enteral feedings. If EN is not feasible, then parenteral nutrition should be initiated as soon as possible in patients who had high nutritional risk on admission. Otherwise, PN should not be initiated during the first week of hospitalization because there is evidence to suggest net harm when initiated early. Supplemental PN may be considered for patients already on EN who are unable to meet more than 60% of their energy and protein requirements by the enteral route alone, but again, this should only be considered after 7-10 days on EN. PN is generally stopped when the patients achieve more than 60% of their energy and protein goals from EN.4

How should patients be monitored while receiving nutritional support?

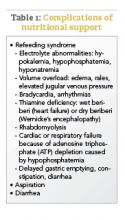

If a patient is severely malnourished and refeeding is initiated, serious complications can occur, which are summarized in Table 1; these complications can include severe electrolyte disorders, fluid shifts, and even death.12 Refeeding syndrome occurs in the first few days of initiating a diet in severely malnourished patients, and its severity is directly related to the severity of malnutrition prior to refeeding. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence created criteria to identify patients at risk for refeeding syndrome; these criteria include having a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2; unintentional weight loss of greater than 10% in the previous 3-6 months; little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days; low levels of potassium, phosphorus, or magnesium before refeeding; and a history of alcohol misuse or taking certain drugs, such as insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics.9

Aspiration is a risk with enteral feeding – the risk factors include being older than 70 years, altered mental status, supine position, and bolus rather than continuous infusion.4 Postpyloric feeding may reduce the risk of aspiration. Expert consensus suggests elevating the head of the bed by 30°-40° for all intubated patients receiving EN, as well as administering chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily.6

Diarrhea is very common in patients receiving EN. After evaluating for other etiologies of diarrhea, tube feeding–associated diarrhea may be managed first by using a fiber-containing formulation. Fiber should be avoided in patients at risk for bowel ischemia or severe dysmotility. If diarrhea persists despite fiber, small peptide formulations, also known as elemental tube feeds, may be used.4,6

Gastric residual volume (GRV) is commonly monitored in patients receiving enteral nutrition. However, the American College of Gastroenterology does not recommend using GRVs to monitor EN feeding because it is a poor marker of clinically meaningful variables, such as gastric emptying, risk of aspiration, and risk of poor outcomes, and increases the risk of tube clogging and inadequate delivery of EN. If GRVs are being monitored, tube feedings should not be withheld because of high GRVs when there are no other signs of intolerance.4 Nausea may be managed by changing a patient from bolus to continuous feedings or by adding promotility agents such as metoclopramide or erythromycin.6

Special considerations in common conditions treated by hospitalists

The principles outlined above are general guidelines that are applicable to most patients requiring nutrition support. We have highlighted special considerations for common conditions in hospitalized patients who require nutritional support below.

Critical Illness

- Defer enteral nutrition until patient is fully resuscitated and hemodynamically stable.

- Severely malnourished or high nutritional-risk patients should be advanced toward goals as quickly as can be tolerated over 24-48 hours.

- Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome or acute lung injury, or those expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours, should receive trophic feeds or full nutrition by enteral route.6

Pancreatitis

- Oral feeding should be attempted as soon as abdominal pain is decreasing and inflammatory markers are improving.13

- A regular solid, low-fat diet should be initiated, rather than slowly advancing from a clear liquid diet.13

- In severe acute pancreatitis, initiation of enteral nutrition within 48 hours of presentation is associated with improved outcomes.13

- There is no difference in outcomes between gastric and postpyloric feeding.14

- Initiation of parenteral nutrition may be delayed for up to 5 days to allow for a trial of oral or enteral feeding.13

Surgical patients

- Consider postponing surgery to provide 7-10 days of preoperative nutrition supplementation in patients with risk of severe undernutrition.16

- Consider postoperative nutritional support if patients are at risk for severe undernutrition, are unable to eat for more than 7 days perioperatively, or are unable to maintain oral intake above 60% of recommended intake for more than 10 days.16

- Consider total parenteral nutrition in cases of impaired gastrointestinal function and absorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, obstructive lesions that do not allow enteral refeeding, or prolonged gastrointestinal failure.16

Prolonged Starvation

- Because of the high risk of refeeding syndrome, patients greater than 30% below ideal body weight should be hospitalized for close monitoring during refeeding.12

- Typical goal for weight gain is no greater than 2-3 pounds per week.10

- Total parenteral nutrition should be reserved for extreme cases, and if used, carbohydrate intake should not exceed 7 mg/kg/min.12

Stroke

- Enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of initial hospitalization if a patient is estimated to require feeding for more than 5 days and/or remain nil per os for 5-7 days.

- If a patient is intubated with increased intracranial pressure, this could delay gastric motility requiring a postpyloric tube placement.

- Initial placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes can be considered if the hospitalized patient is expected to require nutritional support for greater than 30 days. Most patients will have improved dysphagia symptoms within 1 month of their acute stroke, although as many as 40% can have continued dysphagia up to 1 year.10

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted for a common general medical condition, but it is important to recognize that malnutrition was present on admission with weight loss and generalized fluid overload. Furthermore, he is at high nutritional risk because of his low body weight, poor oral intake, and dysphagia. Additionally, the acute inflammation from pneumonia places him in an increased catabolic state.

He was able to maintain some volitional oral intake, but after 7 days of close monitoring by a licensed dietician, it was determined that he was unable to meet his nutritional needs via the oral route. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed, and tube feeds were initiated, because his dysphagia – which was a significant factor contributing to his inability to meet his nutritional needs orally – was expected to persist for greater than 30 days.

Bottom Line

Nutrition support should be initiated in this patient with malnutrition on admission and high nutritional risk.

Dr. Abalos is an assistant professor at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington. Dr. Corbett is an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.

References

1. Correia MI et al. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003 Jun;22(3):235-9.

2. Felder S et al. Association of nutritional risk and adverse medical outcomes across different medical inpatient populations. Nutrition. 2015 Nov-Dec;31(11-12):1385-93.

3. White JV et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 May;112(5):730-8.

4. McClave SA et al. ACG clinical guideline: Nutrition therapy in the adult hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

5. Mueller C et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2011 Jan;35(1):16-24.

6. McClave SA et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016 Feb;40(2):159-211.

7. August D et al. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2002 Jan-Feb:26(1):SUPPL:1SA-138SA.

8. Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

9. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, February 2006. Nutrition support in adults Oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, London. Available from www.rcseng.ac.uk.

10. Corrigan ML et al. Nutrition in the stroke patient. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Jun;26(3):242-52.

11. Loser C et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition – Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;24(5):848-61.

12. Mehler PS et al. Nutritional rehabilitation: Practical guidelines for refeeding the anorectic patient. J Nutr Metab. 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/625782.

13. Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

14. Singh N et al. Evaluation of early enteral feeding through nasogastric and nasojejunal tube in severe acute pancreatitis: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pancreas. 2012 Jan;41(1):153-9.

15. Braga M et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Surgery. Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug;28(4):378-86.

16. Weimann A et al. ESPEN Guidelines on enteral nutrition: Surgery including organ transplantation. Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;25(2):224-44.

Additional reading

- Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the Hospitalized Patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

- McClave SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

Quiz: Recognizing Malnutrition

Which of the following is not a criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition?

A. Weight loss

B. Insufficient energy intake

C. Prealbumin

D. Diminished handgrip strength

Answer: C. Prealbumin. Laboratory indicators of nutrition, such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin, and markers of infection or inflammation are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Because negative acute-phase reactants, they instead can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation

Key Points

- At the time of admission to the hospital, malnutrition is present in 20-50% of patients. All hospitalized patients should be screened for nutritional risk and nutritional support should be considered if patients are not expected to be able to meet nutritional needs for more than 7 days.

- Patients with severe malnutrition on admission, severe critical illness, or severe acute pancreatitis should be provided nutritional support within 24-48 hours.

- Use the gut! Nutritional support should be provided via the most physiologic route possible. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be reserved for patients in whom adequate nutrition cannot be provided enterally.

- Consider a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube if the patient is expected to require tube feedings for more than 30 days.

- Patients with severe malnutrition who are given nutritional support are at high risk of developing refeeding syndrome, which manifests as electrolyte depletions and heart failure or volume overload.

Case

A 60-year-old male with a history of head & neck cancer, treated with radical neck dissection and radiation 5 years prior is admitted with community-acquired pneumonia and anasarca. Prior to admission, he was on a soft dysphagia diet and reports increased difficulty with solid foods and weight loss from 70 kg to 55 kg over 2.5 years. Should nutritional support be initiated?

Background

Malnutrition is associated with increased hospital mortality, decreased functional status and quality of life, infections, longer length of stay, higher hospital costs, and more frequent nonelective readmissions.1,2

Identifying patients who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition

An international consensus committee recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of undernutrition if two of six are present3:

- Insufficient energy intake.

- Weight loss.

- Loss of muscle mass.

- Loss of subcutaneous fat.

- Localized or generalized fluid accumulation that may sometimes mask weight loss.

- Diminished functional status as measured by handgrip strength.

The joint commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours. The American College of Gastroenterologists recommends using a validated score to assess nutritional risk, such as the Nutritional Risk Score (NRS) 2002 or the NUTRIC (Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill) Score, which use a combination of nutritional status and diet-related factors – weight loss, body mass index, and food intake – and also severity of illness measurements.4

- Starvation-related malnutrition, such as anorexia nervosa, presents with a deficiency in calories and protein without inflammation, .

- Chronic disease–related malnutrition, such as that caused chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and obesity, presents with mild to moderate inflammation.

- Acute disease or injury–related malnutrition, such as that caused by sepsis, burns, and trauma, presents with acute and severe inflammation.

Laboratory indicators such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Instead, as negative acute-phase reactants, they can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation.4

Overview of the data

What are the indications for initiating nutritional support, and what is the optimal timing for initiation?

Patients who are malnourished or at significant risk for becoming malnourished should receive specialized nutrition support. Early enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of admission in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk who are unable to maintain volitional intake.6 In the absence of preexisting malnutrition, nutritional support should be provided for patients with inadequate oral intake for 7-14 days or for those in whom inadequate oral intake is expected over the same time period.7

How should nutritional support be administered?

Dietary modification and supplementation

In patients who can tolerate an oral diet, dietary modifications may be made in order to facilitate the provision of essential nutrients in a well-tolerated form. Modifications may include adjusting the consistency of foods, energy value of foods, types of nutrients consumed, and number and frequency of meals.8 Commercial meal replacement beverages are widely used to support a standard oral diet, but there is no data to support their routine use.7

Enteral nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) is the method of choice for administering nutrition support. Contraindications to enteral feeding include diffuse peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and gastrointestinal ischemia.9 The potential advantages of EN over parenteral nutrition (PN) include decreased infection rate, decreased total complications, and shorter length of stay, but there has been no observed difference in mortality. EN is also suggested to have nonnutritional benefits related to providing luminal nutrients – these include maintaining gut integrity, beneficial immune responses, and favorable metabolic responses that help maintain euglycemia and enhance more physiologic fuel utilization.4

Enteral feeding can be administered through the following routes of access:

- Nasogastric tubes: A nasogastric or orogastric tube with radiologic confirmation of positioning is the first line of enteral access. Gastric feeding is preferred because it is well tolerated in the majority of patients, is more physiological, requires a lower level of expertise, and minimizes any delay in initiation of feeding.

- Postpyloric tubes: Postpyloric feeding tubes are indicated if gastric feeding is poorly tolerated or if the patient is at high risk for aspiration because jejunal feedings decrease the incidence of reflux, regurgitation, and aspiration.

- Percutaneous access: When long-term enteral access is required – that is, for greater than 4 weeks – a percutaneous enteral access device should be placed. Prolonged use of a nasoenteric tube may be associated with erosion of the nares and an increase in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia, sinusitis, and esophageal ulceration or stricture. Patients who have had a stroke are the most likely to benefit from percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement, as 40% of patients can have continued dysphagia as long as 1 year after.4,10 Absolute contraindications for PEG placement include serious coagulation disorders (international normalized ratio greater than 1.5; fewer than 50,000 platelets/mcL), sepsis, abdominal wall infections, marked peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritonitis, severe gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or a history of total gastrectomy. Risks often outweigh benefits in patients who have cirrhosis with ascites, patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, and patients who have portal hypertension with gastric varices, but PEG can be considered on a case-by-case basis.11

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition is reserved for patients in whom enteral feeding is contraindicated or who fail to meet their nutritional needs with enteral feedings. If EN is not feasible, then parenteral nutrition should be initiated as soon as possible in patients who had high nutritional risk on admission. Otherwise, PN should not be initiated during the first week of hospitalization because there is evidence to suggest net harm when initiated early. Supplemental PN may be considered for patients already on EN who are unable to meet more than 60% of their energy and protein requirements by the enteral route alone, but again, this should only be considered after 7-10 days on EN. PN is generally stopped when the patients achieve more than 60% of their energy and protein goals from EN.4

How should patients be monitored while receiving nutritional support?

If a patient is severely malnourished and refeeding is initiated, serious complications can occur, which are summarized in Table 1; these complications can include severe electrolyte disorders, fluid shifts, and even death.12 Refeeding syndrome occurs in the first few days of initiating a diet in severely malnourished patients, and its severity is directly related to the severity of malnutrition prior to refeeding. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence created criteria to identify patients at risk for refeeding syndrome; these criteria include having a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2; unintentional weight loss of greater than 10% in the previous 3-6 months; little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days; low levels of potassium, phosphorus, or magnesium before refeeding; and a history of alcohol misuse or taking certain drugs, such as insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics.9

Aspiration is a risk with enteral feeding – the risk factors include being older than 70 years, altered mental status, supine position, and bolus rather than continuous infusion.4 Postpyloric feeding may reduce the risk of aspiration. Expert consensus suggests elevating the head of the bed by 30°-40° for all intubated patients receiving EN, as well as administering chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily.6

Diarrhea is very common in patients receiving EN. After evaluating for other etiologies of diarrhea, tube feeding–associated diarrhea may be managed first by using a fiber-containing formulation. Fiber should be avoided in patients at risk for bowel ischemia or severe dysmotility. If diarrhea persists despite fiber, small peptide formulations, also known as elemental tube feeds, may be used.4,6

Gastric residual volume (GRV) is commonly monitored in patients receiving enteral nutrition. However, the American College of Gastroenterology does not recommend using GRVs to monitor EN feeding because it is a poor marker of clinically meaningful variables, such as gastric emptying, risk of aspiration, and risk of poor outcomes, and increases the risk of tube clogging and inadequate delivery of EN. If GRVs are being monitored, tube feedings should not be withheld because of high GRVs when there are no other signs of intolerance.4 Nausea may be managed by changing a patient from bolus to continuous feedings or by adding promotility agents such as metoclopramide or erythromycin.6

Special considerations in common conditions treated by hospitalists

The principles outlined above are general guidelines that are applicable to most patients requiring nutrition support. We have highlighted special considerations for common conditions in hospitalized patients who require nutritional support below.

Critical Illness

- Defer enteral nutrition until patient is fully resuscitated and hemodynamically stable.

- Severely malnourished or high nutritional-risk patients should be advanced toward goals as quickly as can be tolerated over 24-48 hours.

- Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome or acute lung injury, or those expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours, should receive trophic feeds or full nutrition by enteral route.6

Pancreatitis

- Oral feeding should be attempted as soon as abdominal pain is decreasing and inflammatory markers are improving.13

- A regular solid, low-fat diet should be initiated, rather than slowly advancing from a clear liquid diet.13

- In severe acute pancreatitis, initiation of enteral nutrition within 48 hours of presentation is associated with improved outcomes.13

- There is no difference in outcomes between gastric and postpyloric feeding.14

- Initiation of parenteral nutrition may be delayed for up to 5 days to allow for a trial of oral or enteral feeding.13

Surgical patients

- Consider postponing surgery to provide 7-10 days of preoperative nutrition supplementation in patients with risk of severe undernutrition.16

- Consider postoperative nutritional support if patients are at risk for severe undernutrition, are unable to eat for more than 7 days perioperatively, or are unable to maintain oral intake above 60% of recommended intake for more than 10 days.16

- Consider total parenteral nutrition in cases of impaired gastrointestinal function and absorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, obstructive lesions that do not allow enteral refeeding, or prolonged gastrointestinal failure.16

Prolonged Starvation

- Because of the high risk of refeeding syndrome, patients greater than 30% below ideal body weight should be hospitalized for close monitoring during refeeding.12

- Typical goal for weight gain is no greater than 2-3 pounds per week.10

- Total parenteral nutrition should be reserved for extreme cases, and if used, carbohydrate intake should not exceed 7 mg/kg/min.12

Stroke

- Enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of initial hospitalization if a patient is estimated to require feeding for more than 5 days and/or remain nil per os for 5-7 days.

- If a patient is intubated with increased intracranial pressure, this could delay gastric motility requiring a postpyloric tube placement.

- Initial placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes can be considered if the hospitalized patient is expected to require nutritional support for greater than 30 days. Most patients will have improved dysphagia symptoms within 1 month of their acute stroke, although as many as 40% can have continued dysphagia up to 1 year.10

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted for a common general medical condition, but it is important to recognize that malnutrition was present on admission with weight loss and generalized fluid overload. Furthermore, he is at high nutritional risk because of his low body weight, poor oral intake, and dysphagia. Additionally, the acute inflammation from pneumonia places him in an increased catabolic state.

He was able to maintain some volitional oral intake, but after 7 days of close monitoring by a licensed dietician, it was determined that he was unable to meet his nutritional needs via the oral route. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed, and tube feeds were initiated, because his dysphagia – which was a significant factor contributing to his inability to meet his nutritional needs orally – was expected to persist for greater than 30 days.

Bottom Line

Nutrition support should be initiated in this patient with malnutrition on admission and high nutritional risk.

Dr. Abalos is an assistant professor at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington. Dr. Corbett is an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.

References

1. Correia MI et al. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003 Jun;22(3):235-9.

2. Felder S et al. Association of nutritional risk and adverse medical outcomes across different medical inpatient populations. Nutrition. 2015 Nov-Dec;31(11-12):1385-93.

3. White JV et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 May;112(5):730-8.

4. McClave SA et al. ACG clinical guideline: Nutrition therapy in the adult hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

5. Mueller C et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2011 Jan;35(1):16-24.

6. McClave SA et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016 Feb;40(2):159-211.

7. August D et al. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2002 Jan-Feb:26(1):SUPPL:1SA-138SA.

8. Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

9. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, February 2006. Nutrition support in adults Oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, London. Available from www.rcseng.ac.uk.

10. Corrigan ML et al. Nutrition in the stroke patient. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Jun;26(3):242-52.

11. Loser C et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition – Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;24(5):848-61.

12. Mehler PS et al. Nutritional rehabilitation: Practical guidelines for refeeding the anorectic patient. J Nutr Metab. 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/625782.

13. Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

14. Singh N et al. Evaluation of early enteral feeding through nasogastric and nasojejunal tube in severe acute pancreatitis: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pancreas. 2012 Jan;41(1):153-9.

15. Braga M et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Surgery. Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug;28(4):378-86.

16. Weimann A et al. ESPEN Guidelines on enteral nutrition: Surgery including organ transplantation. Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;25(2):224-44.

Additional reading

- Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the Hospitalized Patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

- McClave SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

Quiz: Recognizing Malnutrition

Which of the following is not a criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition?

A. Weight loss

B. Insufficient energy intake

C. Prealbumin

D. Diminished handgrip strength

Answer: C. Prealbumin. Laboratory indicators of nutrition, such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin, and markers of infection or inflammation are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Because negative acute-phase reactants, they instead can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation

Key Points

- At the time of admission to the hospital, malnutrition is present in 20-50% of patients. All hospitalized patients should be screened for nutritional risk and nutritional support should be considered if patients are not expected to be able to meet nutritional needs for more than 7 days.

- Patients with severe malnutrition on admission, severe critical illness, or severe acute pancreatitis should be provided nutritional support within 24-48 hours.

- Use the gut! Nutritional support should be provided via the most physiologic route possible. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be reserved for patients in whom adequate nutrition cannot be provided enterally.

- Consider a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube if the patient is expected to require tube feedings for more than 30 days.

- Patients with severe malnutrition who are given nutritional support are at high risk of developing refeeding syndrome, which manifests as electrolyte depletions and heart failure or volume overload.

Case

A 60-year-old male with a history of head & neck cancer, treated with radical neck dissection and radiation 5 years prior is admitted with community-acquired pneumonia and anasarca. Prior to admission, he was on a soft dysphagia diet and reports increased difficulty with solid foods and weight loss from 70 kg to 55 kg over 2.5 years. Should nutritional support be initiated?

Background

Malnutrition is associated with increased hospital mortality, decreased functional status and quality of life, infections, longer length of stay, higher hospital costs, and more frequent nonelective readmissions.1,2

Identifying patients who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition

An international consensus committee recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of undernutrition if two of six are present3:

- Insufficient energy intake.

- Weight loss.

- Loss of muscle mass.

- Loss of subcutaneous fat.

- Localized or generalized fluid accumulation that may sometimes mask weight loss.

- Diminished functional status as measured by handgrip strength.

The joint commission requires that all patients admitted to acute care hospitals be screened for risk of malnutrition within 24 hours. The American College of Gastroenterologists recommends using a validated score to assess nutritional risk, such as the Nutritional Risk Score (NRS) 2002 or the NUTRIC (Nutrition Risk in the Critically Ill) Score, which use a combination of nutritional status and diet-related factors – weight loss, body mass index, and food intake – and also severity of illness measurements.4

- Starvation-related malnutrition, such as anorexia nervosa, presents with a deficiency in calories and protein without inflammation, .

- Chronic disease–related malnutrition, such as that caused chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and obesity, presents with mild to moderate inflammation.

- Acute disease or injury–related malnutrition, such as that caused by sepsis, burns, and trauma, presents with acute and severe inflammation.

Laboratory indicators such as albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin are not recommended for the determination of nutritional status. Instead, as negative acute-phase reactants, they can be used as surrogate markers of nutritional risk and degree of inflammation.4

Overview of the data

What are the indications for initiating nutritional support, and what is the optimal timing for initiation?

Patients who are malnourished or at significant risk for becoming malnourished should receive specialized nutrition support. Early enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of admission in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk who are unable to maintain volitional intake.6 In the absence of preexisting malnutrition, nutritional support should be provided for patients with inadequate oral intake for 7-14 days or for those in whom inadequate oral intake is expected over the same time period.7

How should nutritional support be administered?

Dietary modification and supplementation

In patients who can tolerate an oral diet, dietary modifications may be made in order to facilitate the provision of essential nutrients in a well-tolerated form. Modifications may include adjusting the consistency of foods, energy value of foods, types of nutrients consumed, and number and frequency of meals.8 Commercial meal replacement beverages are widely used to support a standard oral diet, but there is no data to support their routine use.7

Enteral nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) is the method of choice for administering nutrition support. Contraindications to enteral feeding include diffuse peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, and gastrointestinal ischemia.9 The potential advantages of EN over parenteral nutrition (PN) include decreased infection rate, decreased total complications, and shorter length of stay, but there has been no observed difference in mortality. EN is also suggested to have nonnutritional benefits related to providing luminal nutrients – these include maintaining gut integrity, beneficial immune responses, and favorable metabolic responses that help maintain euglycemia and enhance more physiologic fuel utilization.4

Enteral feeding can be administered through the following routes of access:

- Nasogastric tubes: A nasogastric or orogastric tube with radiologic confirmation of positioning is the first line of enteral access. Gastric feeding is preferred because it is well tolerated in the majority of patients, is more physiological, requires a lower level of expertise, and minimizes any delay in initiation of feeding.

- Postpyloric tubes: Postpyloric feeding tubes are indicated if gastric feeding is poorly tolerated or if the patient is at high risk for aspiration because jejunal feedings decrease the incidence of reflux, regurgitation, and aspiration.

- Percutaneous access: When long-term enteral access is required – that is, for greater than 4 weeks – a percutaneous enteral access device should be placed. Prolonged use of a nasoenteric tube may be associated with erosion of the nares and an increase in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia, sinusitis, and esophageal ulceration or stricture. Patients who have had a stroke are the most likely to benefit from percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement, as 40% of patients can have continued dysphagia as long as 1 year after.4,10 Absolute contraindications for PEG placement include serious coagulation disorders (international normalized ratio greater than 1.5; fewer than 50,000 platelets/mcL), sepsis, abdominal wall infections, marked peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritonitis, severe gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or a history of total gastrectomy. Risks often outweigh benefits in patients who have cirrhosis with ascites, patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, and patients who have portal hypertension with gastric varices, but PEG can be considered on a case-by-case basis.11

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition is reserved for patients in whom enteral feeding is contraindicated or who fail to meet their nutritional needs with enteral feedings. If EN is not feasible, then parenteral nutrition should be initiated as soon as possible in patients who had high nutritional risk on admission. Otherwise, PN should not be initiated during the first week of hospitalization because there is evidence to suggest net harm when initiated early. Supplemental PN may be considered for patients already on EN who are unable to meet more than 60% of their energy and protein requirements by the enteral route alone, but again, this should only be considered after 7-10 days on EN. PN is generally stopped when the patients achieve more than 60% of their energy and protein goals from EN.4

How should patients be monitored while receiving nutritional support?

If a patient is severely malnourished and refeeding is initiated, serious complications can occur, which are summarized in Table 1; these complications can include severe electrolyte disorders, fluid shifts, and even death.12 Refeeding syndrome occurs in the first few days of initiating a diet in severely malnourished patients, and its severity is directly related to the severity of malnutrition prior to refeeding. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence created criteria to identify patients at risk for refeeding syndrome; these criteria include having a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2; unintentional weight loss of greater than 10% in the previous 3-6 months; little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days; low levels of potassium, phosphorus, or magnesium before refeeding; and a history of alcohol misuse or taking certain drugs, such as insulin, chemotherapy, antacids, or diuretics.9

Aspiration is a risk with enteral feeding – the risk factors include being older than 70 years, altered mental status, supine position, and bolus rather than continuous infusion.4 Postpyloric feeding may reduce the risk of aspiration. Expert consensus suggests elevating the head of the bed by 30°-40° for all intubated patients receiving EN, as well as administering chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily.6

Diarrhea is very common in patients receiving EN. After evaluating for other etiologies of diarrhea, tube feeding–associated diarrhea may be managed first by using a fiber-containing formulation. Fiber should be avoided in patients at risk for bowel ischemia or severe dysmotility. If diarrhea persists despite fiber, small peptide formulations, also known as elemental tube feeds, may be used.4,6

Gastric residual volume (GRV) is commonly monitored in patients receiving enteral nutrition. However, the American College of Gastroenterology does not recommend using GRVs to monitor EN feeding because it is a poor marker of clinically meaningful variables, such as gastric emptying, risk of aspiration, and risk of poor outcomes, and increases the risk of tube clogging and inadequate delivery of EN. If GRVs are being monitored, tube feedings should not be withheld because of high GRVs when there are no other signs of intolerance.4 Nausea may be managed by changing a patient from bolus to continuous feedings or by adding promotility agents such as metoclopramide or erythromycin.6

Special considerations in common conditions treated by hospitalists

The principles outlined above are general guidelines that are applicable to most patients requiring nutrition support. We have highlighted special considerations for common conditions in hospitalized patients who require nutritional support below.

Critical Illness

- Defer enteral nutrition until patient is fully resuscitated and hemodynamically stable.

- Severely malnourished or high nutritional-risk patients should be advanced toward goals as quickly as can be tolerated over 24-48 hours.

- Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome or acute lung injury, or those expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours, should receive trophic feeds or full nutrition by enteral route.6

Pancreatitis

- Oral feeding should be attempted as soon as abdominal pain is decreasing and inflammatory markers are improving.13

- A regular solid, low-fat diet should be initiated, rather than slowly advancing from a clear liquid diet.13

- In severe acute pancreatitis, initiation of enteral nutrition within 48 hours of presentation is associated with improved outcomes.13

- There is no difference in outcomes between gastric and postpyloric feeding.14

- Initiation of parenteral nutrition may be delayed for up to 5 days to allow for a trial of oral or enteral feeding.13

Surgical patients

- Consider postponing surgery to provide 7-10 days of preoperative nutrition supplementation in patients with risk of severe undernutrition.16

- Consider postoperative nutritional support if patients are at risk for severe undernutrition, are unable to eat for more than 7 days perioperatively, or are unable to maintain oral intake above 60% of recommended intake for more than 10 days.16

- Consider total parenteral nutrition in cases of impaired gastrointestinal function and absorption, high output enterocutaneous fistulae, obstructive lesions that do not allow enteral refeeding, or prolonged gastrointestinal failure.16

Prolonged Starvation

- Because of the high risk of refeeding syndrome, patients greater than 30% below ideal body weight should be hospitalized for close monitoring during refeeding.12

- Typical goal for weight gain is no greater than 2-3 pounds per week.10

- Total parenteral nutrition should be reserved for extreme cases, and if used, carbohydrate intake should not exceed 7 mg/kg/min.12

Stroke

- Enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24-48 hours of initial hospitalization if a patient is estimated to require feeding for more than 5 days and/or remain nil per os for 5-7 days.

- If a patient is intubated with increased intracranial pressure, this could delay gastric motility requiring a postpyloric tube placement.

- Initial placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes can be considered if the hospitalized patient is expected to require nutritional support for greater than 30 days. Most patients will have improved dysphagia symptoms within 1 month of their acute stroke, although as many as 40% can have continued dysphagia up to 1 year.10

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted for a common general medical condition, but it is important to recognize that malnutrition was present on admission with weight loss and generalized fluid overload. Furthermore, he is at high nutritional risk because of his low body weight, poor oral intake, and dysphagia. Additionally, the acute inflammation from pneumonia places him in an increased catabolic state.

He was able to maintain some volitional oral intake, but after 7 days of close monitoring by a licensed dietician, it was determined that he was unable to meet his nutritional needs via the oral route. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed, and tube feeds were initiated, because his dysphagia – which was a significant factor contributing to his inability to meet his nutritional needs orally – was expected to persist for greater than 30 days.

Bottom Line

Nutrition support should be initiated in this patient with malnutrition on admission and high nutritional risk.

Dr. Abalos is an assistant professor at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington. Dr. Corbett is an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.

References

1. Correia MI et al. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003 Jun;22(3):235-9.

2. Felder S et al. Association of nutritional risk and adverse medical outcomes across different medical inpatient populations. Nutrition. 2015 Nov-Dec;31(11-12):1385-93.

3. White JV et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 May;112(5):730-8.

4. McClave SA et al. ACG clinical guideline: Nutrition therapy in the adult hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

5. Mueller C et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2011 Jan;35(1):16-24.

6. McClave SA et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016 Feb;40(2):159-211.

7. August D et al. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2002 Jan-Feb:26(1):SUPPL:1SA-138SA.

8. Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

9. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, February 2006. Nutrition support in adults Oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, London. Available from www.rcseng.ac.uk.

10. Corrigan ML et al. Nutrition in the stroke patient. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Jun;26(3):242-52.

11. Loser C et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition – Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;24(5):848-61.

12. Mehler PS et al. Nutritional rehabilitation: Practical guidelines for refeeding the anorectic patient. J Nutr Metab. 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/625782.

13. Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013 Jul-Aug;13(4 Suppl 2):e1-15.

14. Singh N et al. Evaluation of early enteral feeding through nasogastric and nasojejunal tube in severe acute pancreatitis: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pancreas. 2012 Jan;41(1):153-9.

15. Braga M et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Surgery. Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug;28(4):378-86.

16. Weimann A et al. ESPEN Guidelines on enteral nutrition: Surgery including organ transplantation. Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;25(2):224-44.

Additional reading

- Kirkland LL et al. Nutrition in the Hospitalized Patient. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):52-8.

- McClave SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition Therapy in the Adult Hospitalized Patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar;111(3):315-334.

Quiz: Recognizing Malnutrition

Which of the following is not a criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition?

A. Weight loss

B. Insufficient energy intake