User login

Leveling the Playing Field: Accounting for Academic Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

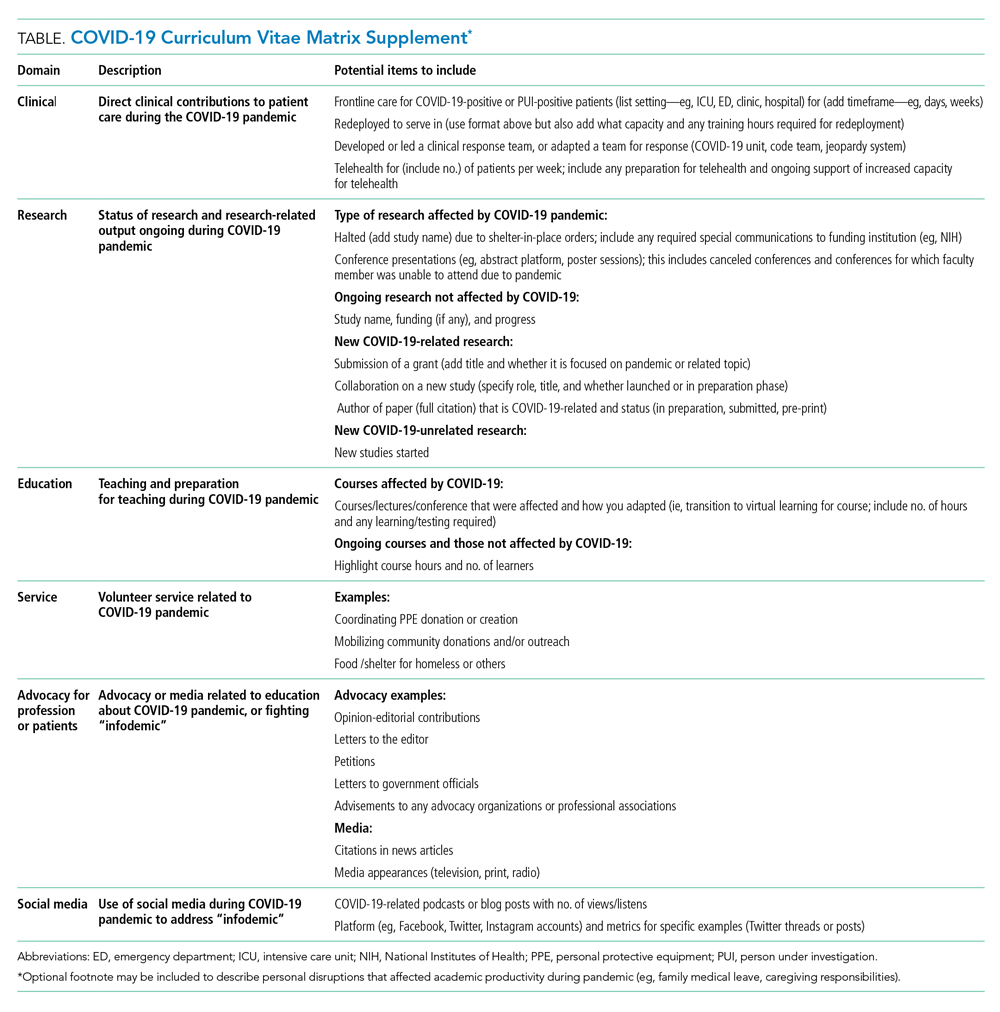

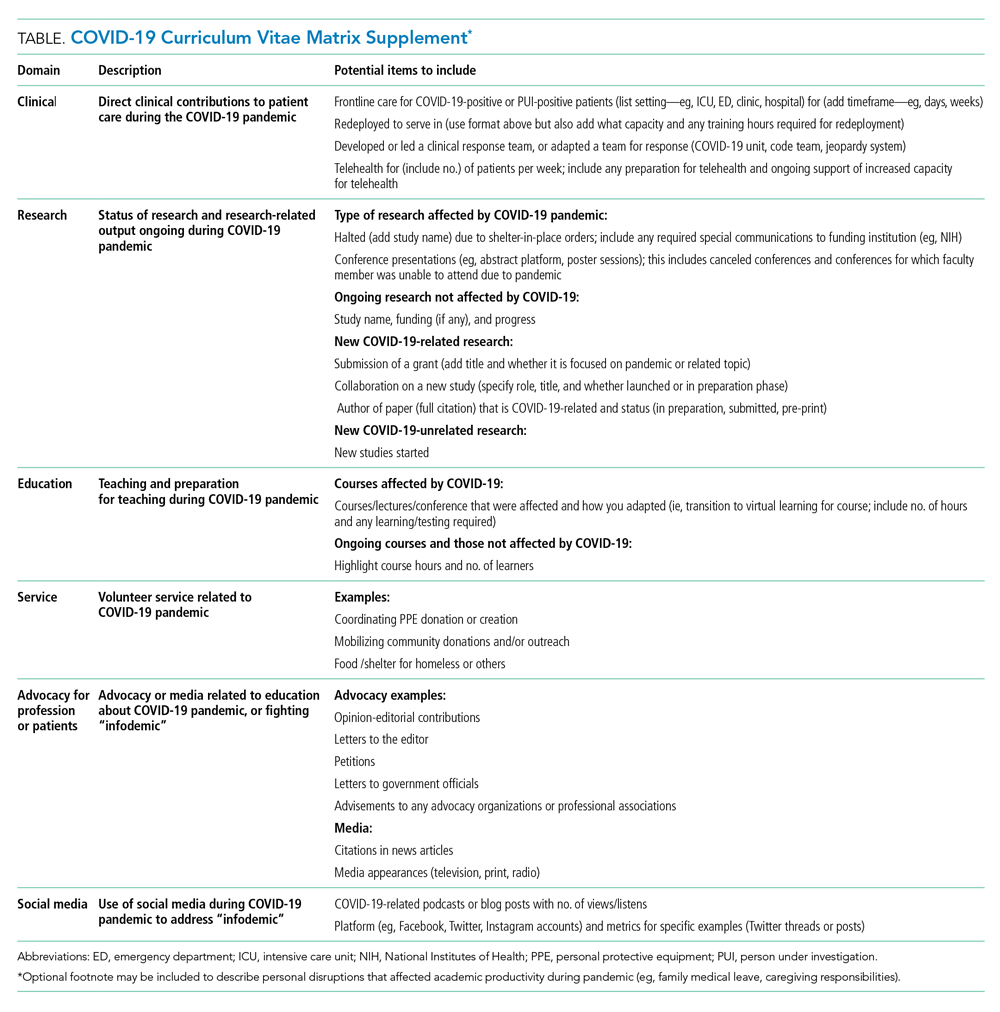

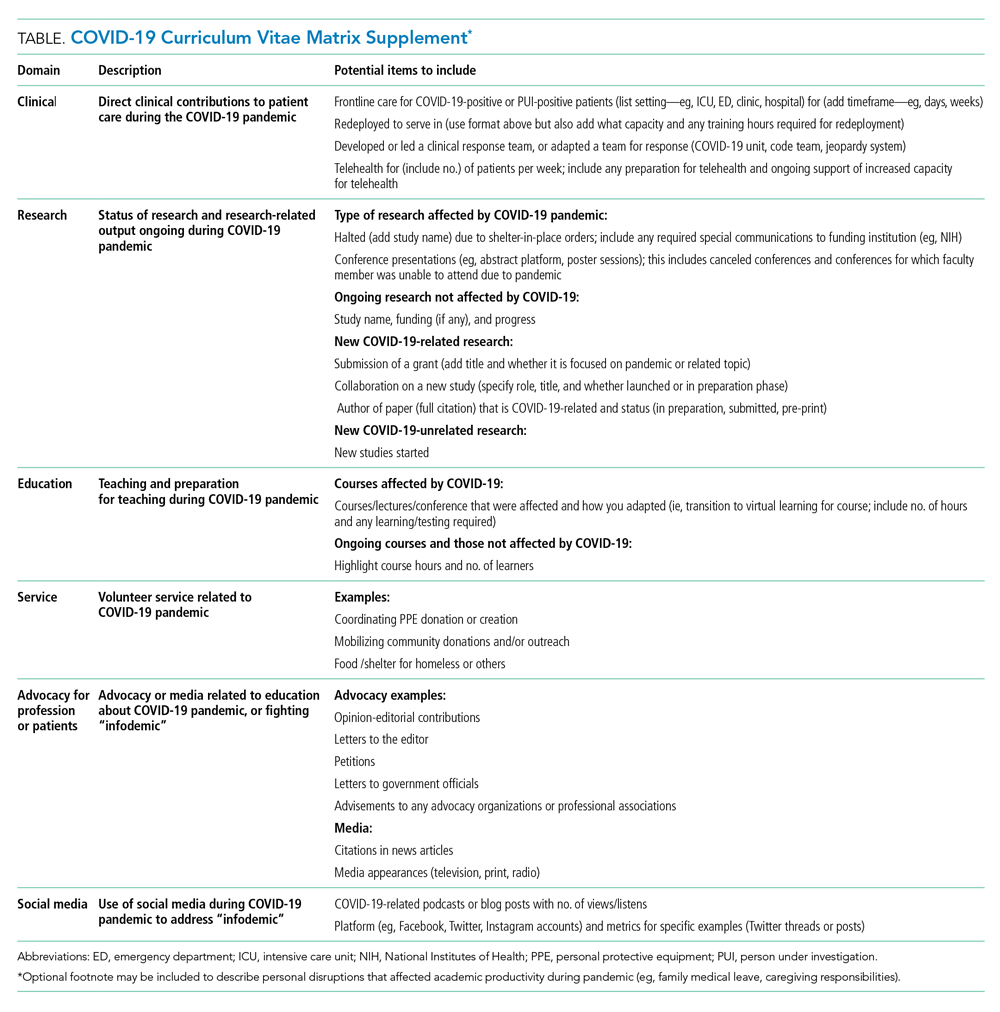

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

9. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2020;29:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003782. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003782

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

9. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2020;29:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003782. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003782

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

9. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2020;29:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003782. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003782

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine