User login

Gender-Based Discrimination and Sexual Harassment Among Academic Internal Medicine Hospitalists

Gender-based discrimination refers to “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of socially constructed gender roles and norms which prevents a person from enjoying full human rights.”1 Similarly, sexual harassment encompasses a spectrum of sexual conduct that includes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature,” as defined by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.2 Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment can be “overt,” which includes explicitly recognizable behaviors, or they can be “implicit,” which includes verbal and nonverbal behaviors that often go unrecognized but convey hostility, objectification, or exclusion of another person. Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are commonly described and likely more prevalent in academic settings.3-6 Female physicians are disproportionately affected by gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, compared with their male peers.4,7

Female physicians face workplace harassment from both patients and coworkers. A study in Canada reported that more than 75% of female physicians experienced sexual harassment from their patients.8 A recent study showed almost half of the physicians who reported harassment, which was three times more often among female physicians, described other physician colleagues as perpetrators.9 In a study among clinician-researchers in the field of academic medicine, 30% of females reported having experienced sexual harassment, compared with 4% of males.7 Among females who reported harassment in this study, 47% stated that these experiences adversely affected their opportunities for career advancement. Career stage may also affect experiences or perceptions of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, with females in earlier career stages reporting a less favorable environment of gender equity.10

Hospital medicine is a young and evolving specialty, and the number of hospitalists has increased substantially from a few hundred at the time of inception to over 50,000 as of 2016.11 The proportion of female hospitalists increased from 31% in 2012 to 52% in 2014, reflecting equal gender representation in hospital medicine.12 Available evidence shows gender disparities exist in hospital medicine disproportionately affecting female hospitalists in their career advancement, including leadership and scholarship opportunities.13 However, there remains a knowledge gap regarding the prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment experienced by hospitalists.

Our study examines the experiences of academic hospitalists regarding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment and the impact of gender on career satisfaction and advancement.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

An online survey was developed and approved by the institutional board review (IRB) at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. University-based academic centers with hospitalist programs, identified through personal connections, from across the continental United Stated were identified as potential study sites, and leaders at each institution were contacted to ascertain potential participation in the survey. The survey was distributed to Internal Medicine hospitalists at 18 participating academic institutions from January 2019 to June 2019. Participation was voluntary. The cover letter explained the purpose of the study and provided a link to the survey. To maintain anonymity, none of the questionnaires requested identifying information from participants. A web-based Qualtrics online-based survey platform was used.

Survey Elements

The survey aimed to assess several elements of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment. All questions about these experiences distinguished encounters with patients from those with colleagues, and questions about occurrences either over a career or in the last 30 days were intended to capture both distant and recent timeframes. The theme for the questions for the survey was based on previous studies.4,7,8 The wording of questions was simplified to make them easily understandable, and the brevity of the survey was maintained to prevent possible nonresponses.14 Additional questions (mistaken for a healthcare provider other than a physician, feeling respected by patients and colleagues, referred to by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent), which were deemed relevant in day-to-day clinical practice through consensus among study investigators and discussions among peer hospitalists, were incorporated into the final survey (Appendix). Survey questions were intended to capture several elements regarding interactions with patients and with colleagues or other healthcare providers (HCPs).

Questions on gender-based discrimination included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] mistaken you for a healthcare provider other than a physician?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] asked you to do something not at your level of training?

- Do you feel respected? Do you perceive your gender has impacted opportunities for your career advancement?

Questions on sexual harassment included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] touched you inappropriately, made sexual remarks or gestures, or made suggestive looks?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] referred to you by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent?

In addition, the survey sought demographic information of the participants (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and information about their individual institutions (names and locations) (Appendix). The geographical locations of the institutions were further categorized into four different regions according to the United States Census Bureau (Northwest, Midwest, South, and West). At the end of the survey, participants were given an opportunity to provide any additional comments.

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive summary statistics were used for demographic data. Associations between the variables were analyzed using chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. The variations among institution-based responses were presented in the form of inter-quartile range (IQR). All tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics software version 24. Relevant responses representative of the overall respondents’ sentiments as provided under additional comment section were discussed and cited.

RESULTS

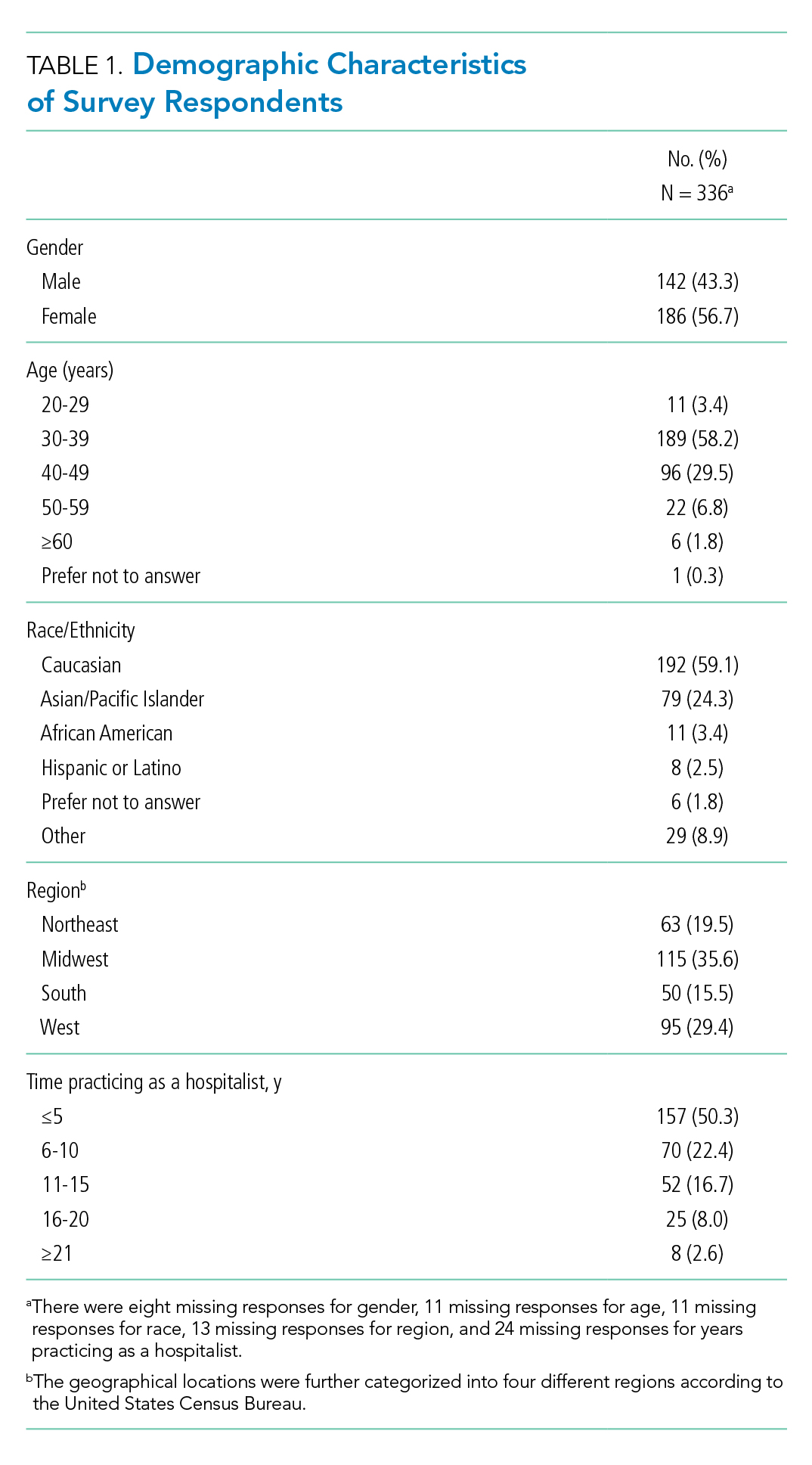

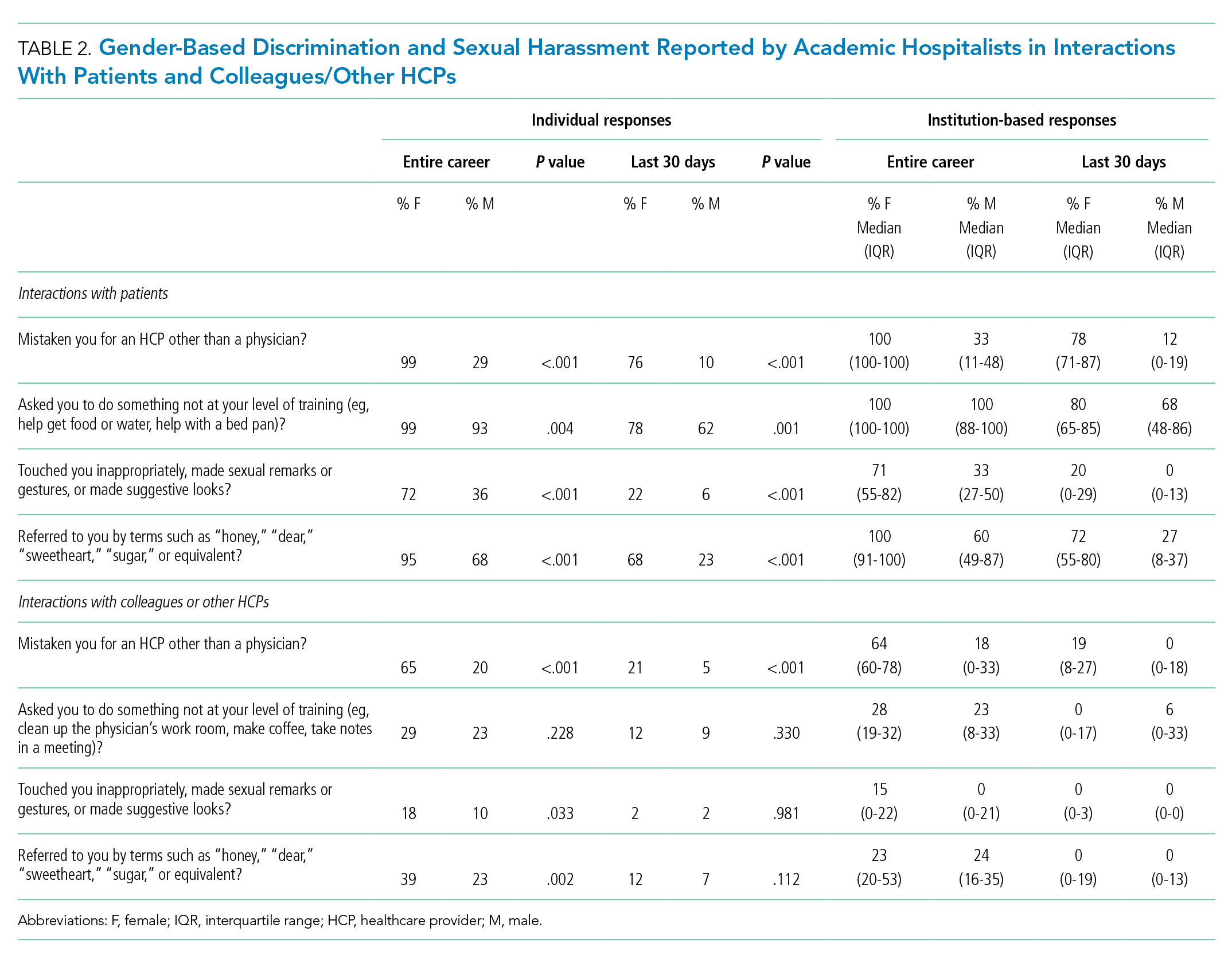

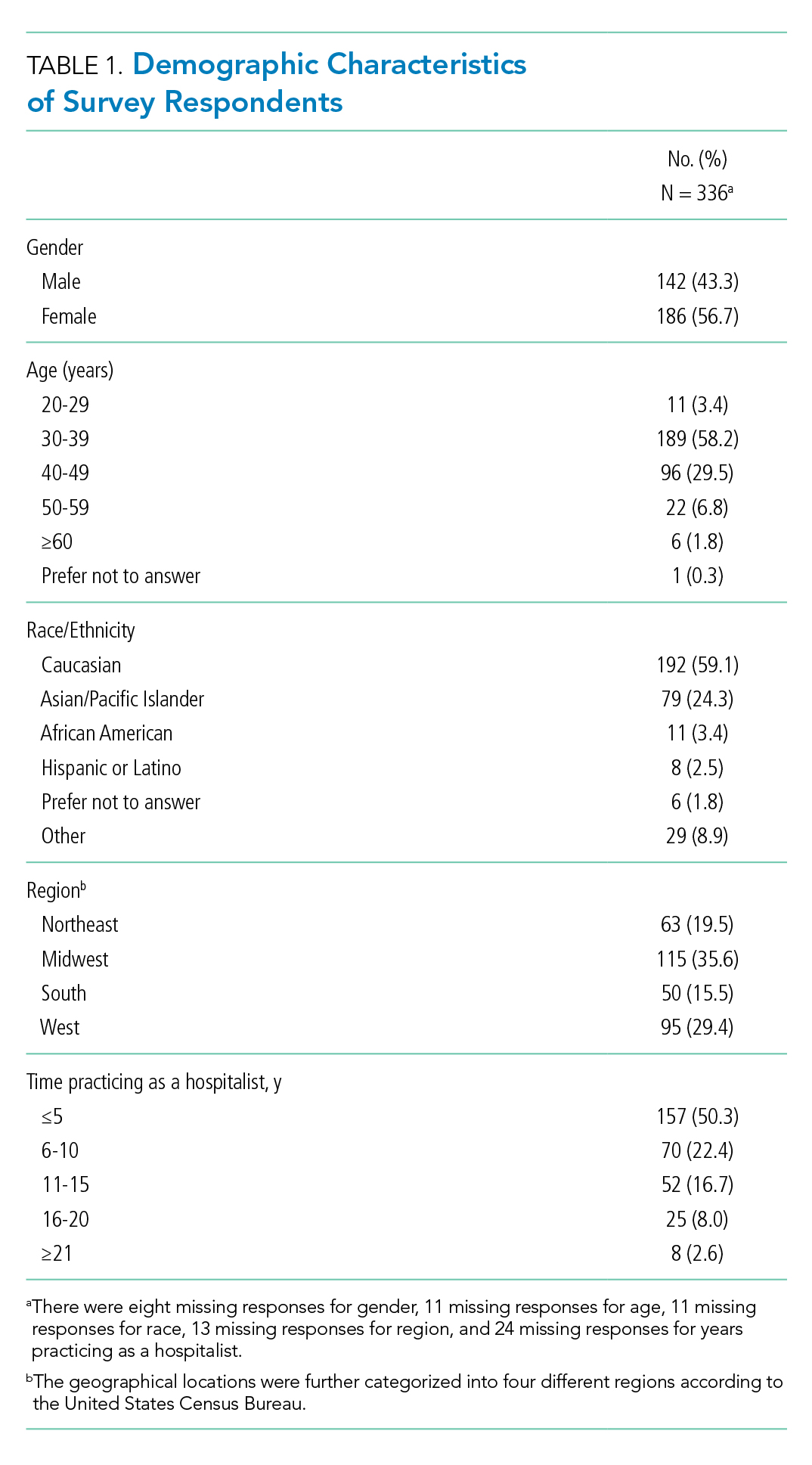

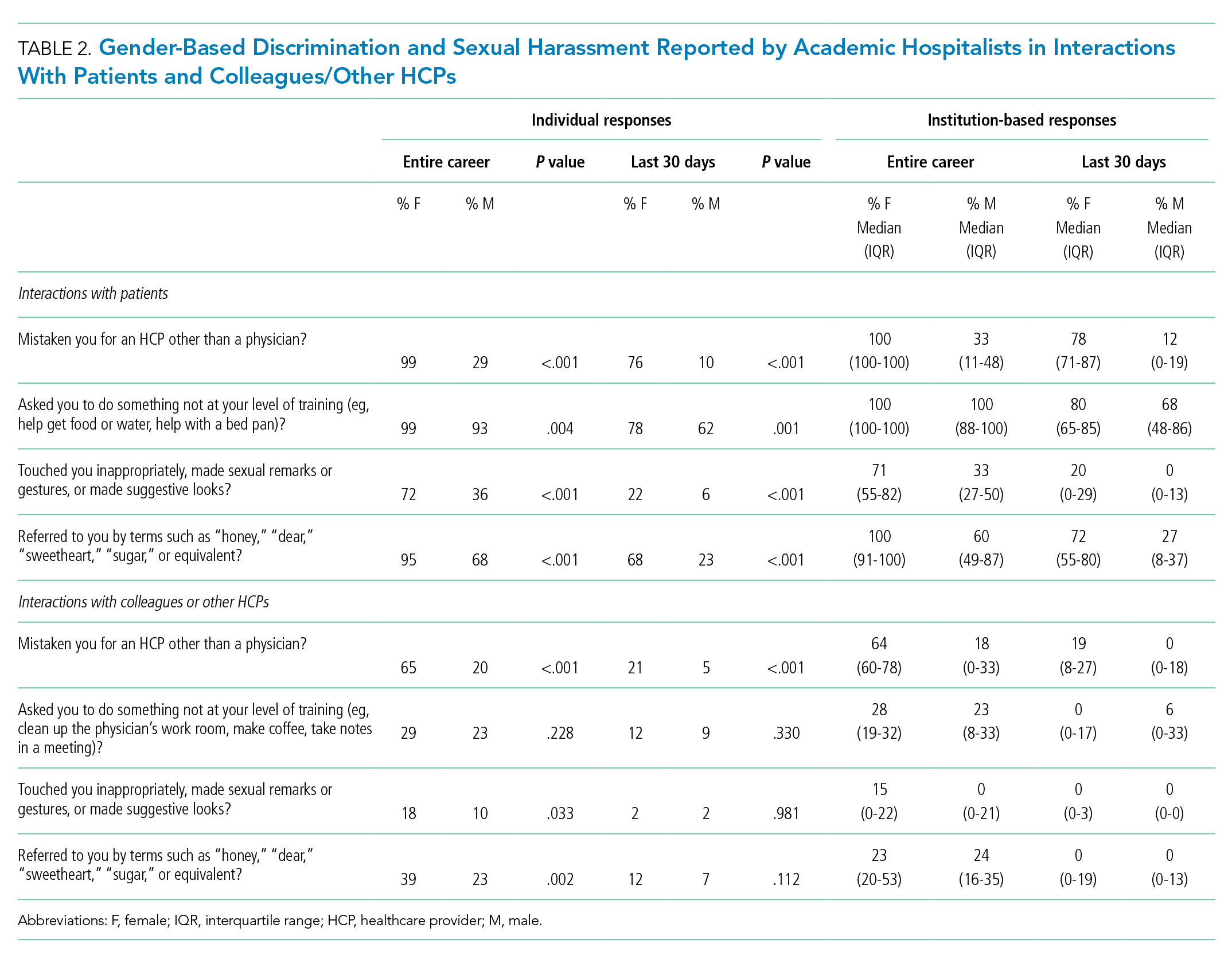

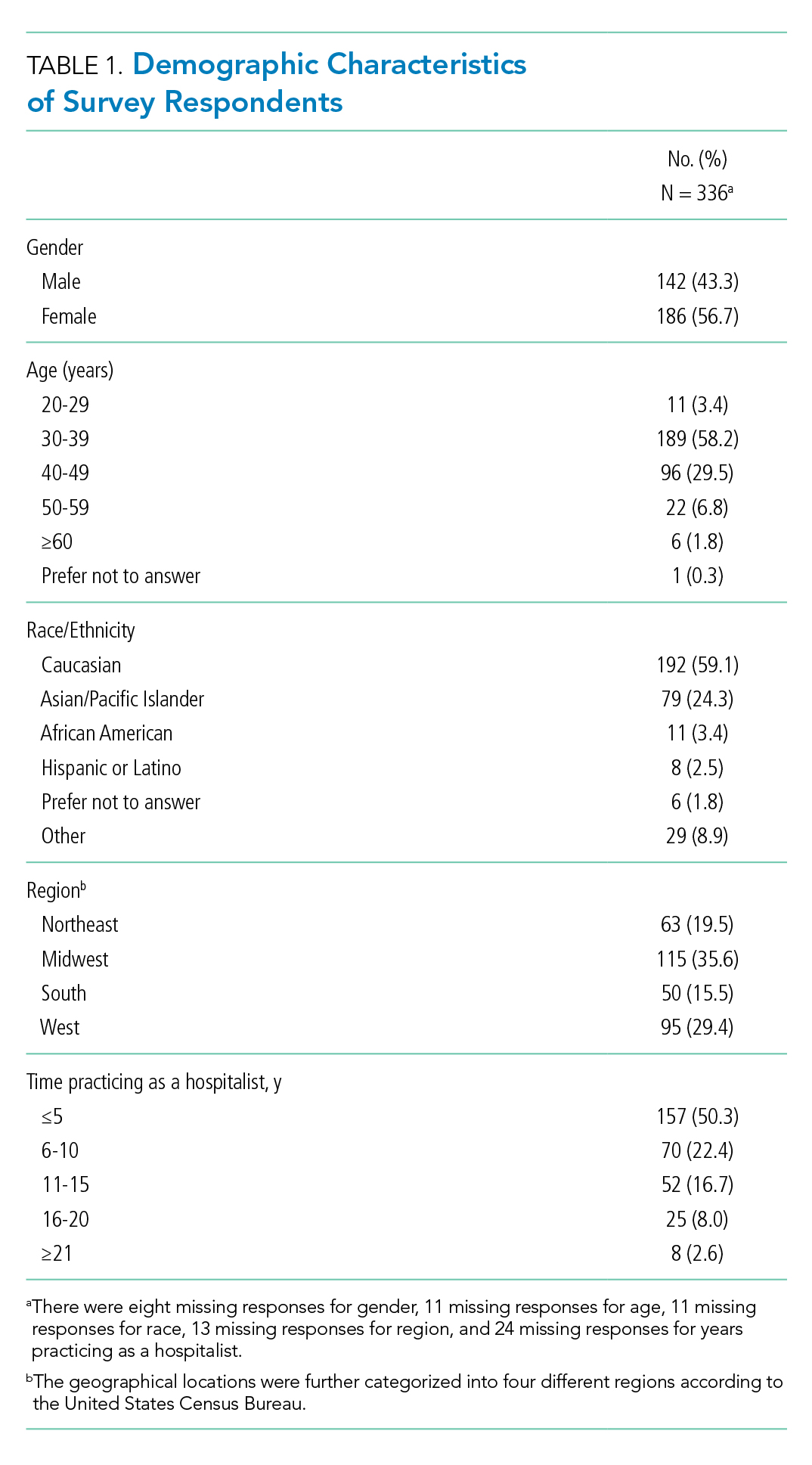

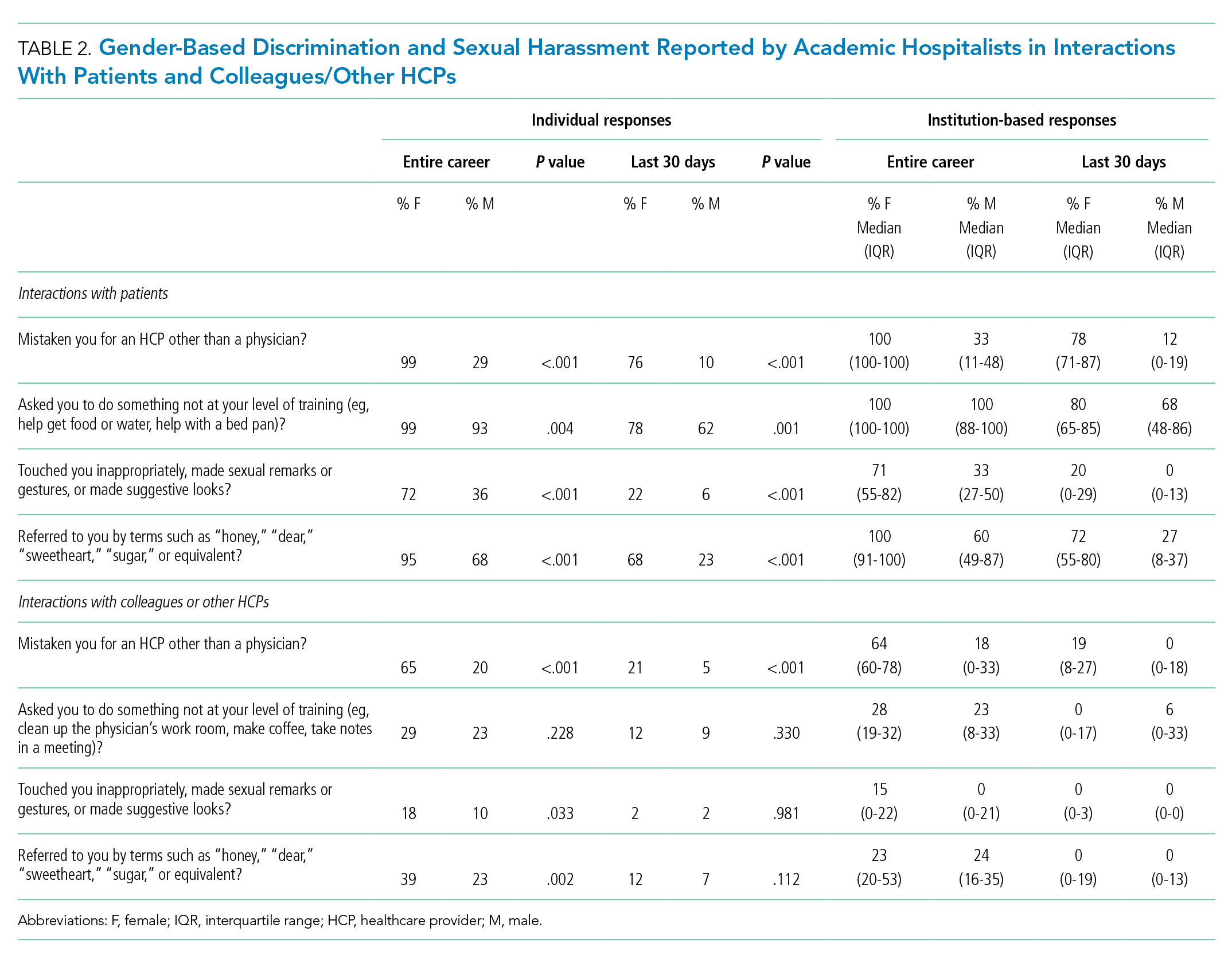

Eighteen different academic institutions across the United States participated in the study, with 336 individual responses. The majority of respondents were females (57%), in younger age categories (58% were 30-39 years old), Caucasian (59%), and early-career hospitalists (>50% working as hospitalists for ≤5 years) (Table 1). Regarding the overall geographic distribution, the largest number of responses were from the Midwest (n = 115; 35.6%) (Table 1 and Appendix).

Gender Discrimination

Interactions With Patients

Over their careers, 69% of hospitalists reported being mistaken for an HCP other than a physician by patients. This was more common among females than among males (99% vs 29%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Almost half (48%) reported this had occurred in the last 30 days, more frequently by females (76% vs 10%; P < .001).

Of responding hospitalists, 96% stated that, over their careers, they have been asked by patients to do something they did not consider to be at their level of training (eg, help get food or water, help with a bed pan), with a higher prevalence of such experiences among females than males (99% vs 93%, respectively; P = .004) (Table 2). Most (71%) said they had experienced this in the last 30 days, which was again more frequently reported by females (78% vs 62%; P = .001).

The responses from female hospitalists regarding their career-long experiences of being mistaken for an HCP or asked to do something not at their level of training by their patients had both the highest number of positive responses across institutions (median of hospital proportions, 100%) and the least institutional variation since both had the narrowest IQR) (Table 2).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Among hospitalists responding to the survey, 46% felt that, over their careers, they had been mistaken for nonphysician HCPs by colleagues or other HCPs. This was more prevalent among females than among males (65% vs 20%; P < .001) (Table 2). Among respondents, 14% reported these events had occurred in the last 30 days, which was again more common among females (21% vs 5%; P < .001).

Over their careers, 26% of hospitalists reported they have been asked by a colleague or HCP to do something not at their level of training (eg, clean up the physician’s work room, make coffee, take notes in a meeting), with similar prevalence among females and males (29% vs 23%; P = .228). Ten percent reported these occurrences in the last 30 days, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 9%; P = .330).

Feelings of Respect and Opportunities for Career Advancement

When asked to rate the statement “I feel respected by patients” on a 5-point Likert scale, female hospitalists overall scored significantly lower as compared with their male counterparts (mean score, 3.73 vs 4.04; P < .001) (Table 3); this was also true when asked about feelings of respect by physicians (mean score, 3.84 vs 4.15; P < .001). Female hospitalists were more likely than males to report that their gender has more negatively impacted their opportunities for career advancement (mean score, 2.73 vs 3.34; P < .001).

Sexual Harassment

Interactions With Patients

Over half (57%) of hospitalists reported career-long experiences of patient(s) touching them inappropriately, making sexual remarks or gestures, or making suggestive looks. These experiences were more prevalent among females than among males (72% vs 36%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Fifteen percent said they had such experience in rhe last 30 days, which was also more common among females (22% vs 6%; P < .001).

Most hospitalists (84%) reported that patients have referred to them by inappropriately familiar terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent over their careers, with females more frequently reporting these behaviors (95% vs 68%; P < .001). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 48%, which was again more common among females (68% vs 23%; P < .001).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Within their careers, 15% of hospitalists reported at least one experience of a colleague or HCP touching them inappropriately or making sexual remarks, gestures, or suggestive looks. This was more prevalent for females than males (18% vs 10%, respectively; P = .033). Only 2% of both females and males reported these experiences in the last 30 days (2% vs 2%; P = .981).

Almost one-third of participants (32%) affirmed that another HCP has referred to them by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent in their career, with a higher proportion of females than males reporting these events (39% vs 23%; P = .002) (Table 2). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 10%, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 7%; P = .112).

Additional Comments From Respondents

- “Throughout my training and now into my professional career, there are nearly weekly incidents of elderly male patients referring to me as “honey/dear/sweetie” or even by my first name, even though I introduce myself as their physician and politely correct them. They will often refer to me as a nurse and ask me to do something not at my level of training. Sometimes even despite correcting the patient, they continue to refer to me as such. Throughout the years, other female MDs and I have discussed that this is ‘status quo’ for female physicians and observe that this is not an experience that male MDs share.”

- “I frequently round with a male nurse practitioner and the patients almost always, despite introducing ourselves and our roles, turn to him and ask him questions instead of addressing them to me.”

- “Our institution allows female faculty to be interviewed about childcare, household labor division, plans for pregnancy. One professor asks women private details about their private relationships such as what they do with spouse on date night or weekends away.”

- “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. I don’t think it’s unreasonable for people to ask me to do things, no matter my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.”

DISCUSSION

This survey demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common, both in more distant and recent time frames. Notably, these experiences are shared by female and male physicians in interactions with both patients and colleagues, though male hospitalists report most of these experiences at significantly lower frequencies than females. These results support past work showing that female physicians are significantly more likely to be subjected to gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, but also challenges the perception that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are uniquely experienced by females.

A startling number of females and males in the study reported sexual harassment (inappropriate touching, remarks, gestures, and looks) when interacting with patients throughout their careers and in last 30 days. Many males and females reported that patients had referred to them with inappropriately familiar, and potentially demeaning, terms of endearment. For both overt and implicit sexual harassment, females were significantly more likely than males to report experiencing these behaviors when interacting with patients. Although some of these experiences may seem less harmful than others, a meta-analysis demonstrated that frequent, less intense experiences of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have a similar impact on female’s well-being as do less frequent, more intense experiences.15 Although the person using the terms of endearment like “honey,” “sugar,” or “sweetheart” may feel the terms are harmless, such expressions can be inappropriate and constitute sexual harassment according to the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Civil Rights.16 The Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP) also classifies such terms into verbal categories of sexual harrassment.17

Of female physicians surveyed, 99% reported that they had been mistaken for HCPs other than physicians by their patients over their careers. Although this was also reported by male physicians, the experience was 3.4 times as likely for female physicians. Misidentification by patients may represent a disconnect between the growing female representation in the physician workforce and patients’ conceptions of the traditional image of a physician.

In parallel with this finding of misidentification, an interesting area of the study was the question regarding being asked to do “something not at your level of training.” A recurring theme in the comments was a rejection of the notion that certain tasks were “beneath a level of training,” suggesting a common view that acts of caregiving are not bounded by hierarchy. Analysis of qualitative responses showed that 40% of these responses had comments regarding this question. An example was “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.” Notably, however, a larger number of female than male physicians responded yes to this question in both study time frames. This points to a differential in how female physicians are viewed by patients, both in frequent misidentification and in behaviors more frequently asked of female physicians than their male counterparts. Given the comments, it may also suggest a difference in how female and male physicians perceive the fluidity of bounds on their care-taking roles set by their “level of training.”

A large number of study participants were early-career hospitalists, which may in part explain some of the study results. In a previous study of gender equity in an Internal Medicine department, physicians practicing medicine for more than 15 years perceived the departmental culture as more favorable than physicians with shorter careers.10 Additionally, the perception of cultures was most discordant between senior male physicians and junior female physicians.10 Because many hospitalists are early-career physicians, they may have trained in an environment that had heightened awareness surrounding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, which affects the overall study results.

Multiple qualitative comments, mentioned above, were submitted by participants describing their experiences in all categories. Such comments paint a picture of insidious bias and cultural norms affecting the quality of female physicians’ work lives.

Two questions focused on career satisfaction and the sense of respect from patients and colleagues. In both responses, there was a statistically different response between males and females, with females less likely to report that they felt respected and that their gender adversely impacted their opportunities for career advancement. This is disturbing information and warrants more investigation.

The reasons for the observed prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in this broad survey of academic hospitalists are uncertain. Multiple studies to date have demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have historically existed in medicine and continue to even today. Unlike physicians with long-term relationships with patients, hospitalists may face more exposure due to a lack of long-term continuity with patients. The absence of an established trust in the relationship also may make them more vulnerable to inappropriate behaviors when interacting with patients. Hospital medicine, however, is a young specialty with equal gender representation and should be at the forefront of addressing and solving these issues of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment.

The survey had a good distribution between female and male participants. Additionally, the survey reflected the general distribution of the national hospitalist workforce in gender, age, and ethnic/racial distribution, as well as number of years in practice.12 The study surveyed respondents regarding experiences in both long- and short-term time frames, as well as experiences with patients and colleagues.

Our study reflects a cross-sectional snapshot of hospitalists’ perceptions with no longitudinal follow-up. Since the survey was limited to academic medical centers, it may not reflect experiences in community/private practice settings. The small number of participants limited the ability to perform subgroup analyses by age, race, or years in practice, which may play a role in interactions with patients and colleagues. Since the number of respondents varied greatly by institution, a minority of institutions could have influenced some of the findings. Narrow IQRs of the hospital proportions as shown in Table 2 would suggest similar responses across institutions, whereas wide IQRs would suggest that a smaller number of institutions were possibly driving the findings. Because of the survey distribution method, it is unknown how many physicians received the survey and a response rate could not be calculated. Further, selection, recall, and detection biases cannot be ruled out.

CONCLUSION

This survey shows that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common and more frequently experienced by female physicians, both in interactions with patients and colleagues. Our study highlights the need to address this prevalent issue among academic hospitalists.

1. WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health. A training manual for health managers. World Health Organization; 2001. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/RHR_01_29/en/

2. Sexual Harassment. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed Jan 5, 2020. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm

3. Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(4):352-358. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.4.352

4. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):889-96. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00007

5. Bates CK, Jagsi R, Gordon LK, et al. It is time for zero tolerance for sexual harassment in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):163-165. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002050

6. Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1589-1591. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1809846

7. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2188

8. Phillips SP, Schneider MS. Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1936-1939. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199312233292607

9. Kane L. Sexual Harassment of Physicians: Report 2018. Medscape. June 13, 2018. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/sexual-harassment-of-physicians-6010304

10. Ruzycki SM, Freeman G, Bharwani A, Brown A. Association of physician characteristics with perceptions and experiences of gender equity in an academic internal medicine department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915165. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15165

11. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

12. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

13. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

14. Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D; iConnect consortium. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62

15 Sojo VE, Wood RE, Genat AE. Harmful Workplace Experiences and Women’s Occupational Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(1):10-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346

16. Office of Civil Rights: Sexual Harassment. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/Sexual-Harassment

17. Sexual Harassment: Categories of Sexual Harassment. Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP). Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.sexualassault.army.mil/categories_of_harassment.aspx

Gender-based discrimination refers to “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of socially constructed gender roles and norms which prevents a person from enjoying full human rights.”1 Similarly, sexual harassment encompasses a spectrum of sexual conduct that includes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature,” as defined by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.2 Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment can be “overt,” which includes explicitly recognizable behaviors, or they can be “implicit,” which includes verbal and nonverbal behaviors that often go unrecognized but convey hostility, objectification, or exclusion of another person. Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are commonly described and likely more prevalent in academic settings.3-6 Female physicians are disproportionately affected by gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, compared with their male peers.4,7

Female physicians face workplace harassment from both patients and coworkers. A study in Canada reported that more than 75% of female physicians experienced sexual harassment from their patients.8 A recent study showed almost half of the physicians who reported harassment, which was three times more often among female physicians, described other physician colleagues as perpetrators.9 In a study among clinician-researchers in the field of academic medicine, 30% of females reported having experienced sexual harassment, compared with 4% of males.7 Among females who reported harassment in this study, 47% stated that these experiences adversely affected their opportunities for career advancement. Career stage may also affect experiences or perceptions of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, with females in earlier career stages reporting a less favorable environment of gender equity.10

Hospital medicine is a young and evolving specialty, and the number of hospitalists has increased substantially from a few hundred at the time of inception to over 50,000 as of 2016.11 The proportion of female hospitalists increased from 31% in 2012 to 52% in 2014, reflecting equal gender representation in hospital medicine.12 Available evidence shows gender disparities exist in hospital medicine disproportionately affecting female hospitalists in their career advancement, including leadership and scholarship opportunities.13 However, there remains a knowledge gap regarding the prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment experienced by hospitalists.

Our study examines the experiences of academic hospitalists regarding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment and the impact of gender on career satisfaction and advancement.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

An online survey was developed and approved by the institutional board review (IRB) at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. University-based academic centers with hospitalist programs, identified through personal connections, from across the continental United Stated were identified as potential study sites, and leaders at each institution were contacted to ascertain potential participation in the survey. The survey was distributed to Internal Medicine hospitalists at 18 participating academic institutions from January 2019 to June 2019. Participation was voluntary. The cover letter explained the purpose of the study and provided a link to the survey. To maintain anonymity, none of the questionnaires requested identifying information from participants. A web-based Qualtrics online-based survey platform was used.

Survey Elements

The survey aimed to assess several elements of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment. All questions about these experiences distinguished encounters with patients from those with colleagues, and questions about occurrences either over a career or in the last 30 days were intended to capture both distant and recent timeframes. The theme for the questions for the survey was based on previous studies.4,7,8 The wording of questions was simplified to make them easily understandable, and the brevity of the survey was maintained to prevent possible nonresponses.14 Additional questions (mistaken for a healthcare provider other than a physician, feeling respected by patients and colleagues, referred to by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent), which were deemed relevant in day-to-day clinical practice through consensus among study investigators and discussions among peer hospitalists, were incorporated into the final survey (Appendix). Survey questions were intended to capture several elements regarding interactions with patients and with colleagues or other healthcare providers (HCPs).

Questions on gender-based discrimination included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] mistaken you for a healthcare provider other than a physician?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] asked you to do something not at your level of training?

- Do you feel respected? Do you perceive your gender has impacted opportunities for your career advancement?

Questions on sexual harassment included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] touched you inappropriately, made sexual remarks or gestures, or made suggestive looks?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] referred to you by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent?

In addition, the survey sought demographic information of the participants (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and information about their individual institutions (names and locations) (Appendix). The geographical locations of the institutions were further categorized into four different regions according to the United States Census Bureau (Northwest, Midwest, South, and West). At the end of the survey, participants were given an opportunity to provide any additional comments.

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive summary statistics were used for demographic data. Associations between the variables were analyzed using chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. The variations among institution-based responses were presented in the form of inter-quartile range (IQR). All tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics software version 24. Relevant responses representative of the overall respondents’ sentiments as provided under additional comment section were discussed and cited.

RESULTS

Eighteen different academic institutions across the United States participated in the study, with 336 individual responses. The majority of respondents were females (57%), in younger age categories (58% were 30-39 years old), Caucasian (59%), and early-career hospitalists (>50% working as hospitalists for ≤5 years) (Table 1). Regarding the overall geographic distribution, the largest number of responses were from the Midwest (n = 115; 35.6%) (Table 1 and Appendix).

Gender Discrimination

Interactions With Patients

Over their careers, 69% of hospitalists reported being mistaken for an HCP other than a physician by patients. This was more common among females than among males (99% vs 29%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Almost half (48%) reported this had occurred in the last 30 days, more frequently by females (76% vs 10%; P < .001).

Of responding hospitalists, 96% stated that, over their careers, they have been asked by patients to do something they did not consider to be at their level of training (eg, help get food or water, help with a bed pan), with a higher prevalence of such experiences among females than males (99% vs 93%, respectively; P = .004) (Table 2). Most (71%) said they had experienced this in the last 30 days, which was again more frequently reported by females (78% vs 62%; P = .001).

The responses from female hospitalists regarding their career-long experiences of being mistaken for an HCP or asked to do something not at their level of training by their patients had both the highest number of positive responses across institutions (median of hospital proportions, 100%) and the least institutional variation since both had the narrowest IQR) (Table 2).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Among hospitalists responding to the survey, 46% felt that, over their careers, they had been mistaken for nonphysician HCPs by colleagues or other HCPs. This was more prevalent among females than among males (65% vs 20%; P < .001) (Table 2). Among respondents, 14% reported these events had occurred in the last 30 days, which was again more common among females (21% vs 5%; P < .001).

Over their careers, 26% of hospitalists reported they have been asked by a colleague or HCP to do something not at their level of training (eg, clean up the physician’s work room, make coffee, take notes in a meeting), with similar prevalence among females and males (29% vs 23%; P = .228). Ten percent reported these occurrences in the last 30 days, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 9%; P = .330).

Feelings of Respect and Opportunities for Career Advancement

When asked to rate the statement “I feel respected by patients” on a 5-point Likert scale, female hospitalists overall scored significantly lower as compared with their male counterparts (mean score, 3.73 vs 4.04; P < .001) (Table 3); this was also true when asked about feelings of respect by physicians (mean score, 3.84 vs 4.15; P < .001). Female hospitalists were more likely than males to report that their gender has more negatively impacted their opportunities for career advancement (mean score, 2.73 vs 3.34; P < .001).

Sexual Harassment

Interactions With Patients

Over half (57%) of hospitalists reported career-long experiences of patient(s) touching them inappropriately, making sexual remarks or gestures, or making suggestive looks. These experiences were more prevalent among females than among males (72% vs 36%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Fifteen percent said they had such experience in rhe last 30 days, which was also more common among females (22% vs 6%; P < .001).

Most hospitalists (84%) reported that patients have referred to them by inappropriately familiar terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent over their careers, with females more frequently reporting these behaviors (95% vs 68%; P < .001). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 48%, which was again more common among females (68% vs 23%; P < .001).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Within their careers, 15% of hospitalists reported at least one experience of a colleague or HCP touching them inappropriately or making sexual remarks, gestures, or suggestive looks. This was more prevalent for females than males (18% vs 10%, respectively; P = .033). Only 2% of both females and males reported these experiences in the last 30 days (2% vs 2%; P = .981).

Almost one-third of participants (32%) affirmed that another HCP has referred to them by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent in their career, with a higher proportion of females than males reporting these events (39% vs 23%; P = .002) (Table 2). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 10%, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 7%; P = .112).

Additional Comments From Respondents

- “Throughout my training and now into my professional career, there are nearly weekly incidents of elderly male patients referring to me as “honey/dear/sweetie” or even by my first name, even though I introduce myself as their physician and politely correct them. They will often refer to me as a nurse and ask me to do something not at my level of training. Sometimes even despite correcting the patient, they continue to refer to me as such. Throughout the years, other female MDs and I have discussed that this is ‘status quo’ for female physicians and observe that this is not an experience that male MDs share.”

- “I frequently round with a male nurse practitioner and the patients almost always, despite introducing ourselves and our roles, turn to him and ask him questions instead of addressing them to me.”

- “Our institution allows female faculty to be interviewed about childcare, household labor division, plans for pregnancy. One professor asks women private details about their private relationships such as what they do with spouse on date night or weekends away.”

- “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. I don’t think it’s unreasonable for people to ask me to do things, no matter my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.”

DISCUSSION

This survey demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common, both in more distant and recent time frames. Notably, these experiences are shared by female and male physicians in interactions with both patients and colleagues, though male hospitalists report most of these experiences at significantly lower frequencies than females. These results support past work showing that female physicians are significantly more likely to be subjected to gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, but also challenges the perception that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are uniquely experienced by females.

A startling number of females and males in the study reported sexual harassment (inappropriate touching, remarks, gestures, and looks) when interacting with patients throughout their careers and in last 30 days. Many males and females reported that patients had referred to them with inappropriately familiar, and potentially demeaning, terms of endearment. For both overt and implicit sexual harassment, females were significantly more likely than males to report experiencing these behaviors when interacting with patients. Although some of these experiences may seem less harmful than others, a meta-analysis demonstrated that frequent, less intense experiences of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have a similar impact on female’s well-being as do less frequent, more intense experiences.15 Although the person using the terms of endearment like “honey,” “sugar,” or “sweetheart” may feel the terms are harmless, such expressions can be inappropriate and constitute sexual harassment according to the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Civil Rights.16 The Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP) also classifies such terms into verbal categories of sexual harrassment.17

Of female physicians surveyed, 99% reported that they had been mistaken for HCPs other than physicians by their patients over their careers. Although this was also reported by male physicians, the experience was 3.4 times as likely for female physicians. Misidentification by patients may represent a disconnect between the growing female representation in the physician workforce and patients’ conceptions of the traditional image of a physician.

In parallel with this finding of misidentification, an interesting area of the study was the question regarding being asked to do “something not at your level of training.” A recurring theme in the comments was a rejection of the notion that certain tasks were “beneath a level of training,” suggesting a common view that acts of caregiving are not bounded by hierarchy. Analysis of qualitative responses showed that 40% of these responses had comments regarding this question. An example was “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.” Notably, however, a larger number of female than male physicians responded yes to this question in both study time frames. This points to a differential in how female physicians are viewed by patients, both in frequent misidentification and in behaviors more frequently asked of female physicians than their male counterparts. Given the comments, it may also suggest a difference in how female and male physicians perceive the fluidity of bounds on their care-taking roles set by their “level of training.”

A large number of study participants were early-career hospitalists, which may in part explain some of the study results. In a previous study of gender equity in an Internal Medicine department, physicians practicing medicine for more than 15 years perceived the departmental culture as more favorable than physicians with shorter careers.10 Additionally, the perception of cultures was most discordant between senior male physicians and junior female physicians.10 Because many hospitalists are early-career physicians, they may have trained in an environment that had heightened awareness surrounding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, which affects the overall study results.

Multiple qualitative comments, mentioned above, were submitted by participants describing their experiences in all categories. Such comments paint a picture of insidious bias and cultural norms affecting the quality of female physicians’ work lives.

Two questions focused on career satisfaction and the sense of respect from patients and colleagues. In both responses, there was a statistically different response between males and females, with females less likely to report that they felt respected and that their gender adversely impacted their opportunities for career advancement. This is disturbing information and warrants more investigation.

The reasons for the observed prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in this broad survey of academic hospitalists are uncertain. Multiple studies to date have demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have historically existed in medicine and continue to even today. Unlike physicians with long-term relationships with patients, hospitalists may face more exposure due to a lack of long-term continuity with patients. The absence of an established trust in the relationship also may make them more vulnerable to inappropriate behaviors when interacting with patients. Hospital medicine, however, is a young specialty with equal gender representation and should be at the forefront of addressing and solving these issues of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment.

The survey had a good distribution between female and male participants. Additionally, the survey reflected the general distribution of the national hospitalist workforce in gender, age, and ethnic/racial distribution, as well as number of years in practice.12 The study surveyed respondents regarding experiences in both long- and short-term time frames, as well as experiences with patients and colleagues.

Our study reflects a cross-sectional snapshot of hospitalists’ perceptions with no longitudinal follow-up. Since the survey was limited to academic medical centers, it may not reflect experiences in community/private practice settings. The small number of participants limited the ability to perform subgroup analyses by age, race, or years in practice, which may play a role in interactions with patients and colleagues. Since the number of respondents varied greatly by institution, a minority of institutions could have influenced some of the findings. Narrow IQRs of the hospital proportions as shown in Table 2 would suggest similar responses across institutions, whereas wide IQRs would suggest that a smaller number of institutions were possibly driving the findings. Because of the survey distribution method, it is unknown how many physicians received the survey and a response rate could not be calculated. Further, selection, recall, and detection biases cannot be ruled out.

CONCLUSION

This survey shows that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common and more frequently experienced by female physicians, both in interactions with patients and colleagues. Our study highlights the need to address this prevalent issue among academic hospitalists.

Gender-based discrimination refers to “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of socially constructed gender roles and norms which prevents a person from enjoying full human rights.”1 Similarly, sexual harassment encompasses a spectrum of sexual conduct that includes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature,” as defined by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.2 Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment can be “overt,” which includes explicitly recognizable behaviors, or they can be “implicit,” which includes verbal and nonverbal behaviors that often go unrecognized but convey hostility, objectification, or exclusion of another person. Gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are commonly described and likely more prevalent in academic settings.3-6 Female physicians are disproportionately affected by gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, compared with their male peers.4,7

Female physicians face workplace harassment from both patients and coworkers. A study in Canada reported that more than 75% of female physicians experienced sexual harassment from their patients.8 A recent study showed almost half of the physicians who reported harassment, which was three times more often among female physicians, described other physician colleagues as perpetrators.9 In a study among clinician-researchers in the field of academic medicine, 30% of females reported having experienced sexual harassment, compared with 4% of males.7 Among females who reported harassment in this study, 47% stated that these experiences adversely affected their opportunities for career advancement. Career stage may also affect experiences or perceptions of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, with females in earlier career stages reporting a less favorable environment of gender equity.10

Hospital medicine is a young and evolving specialty, and the number of hospitalists has increased substantially from a few hundred at the time of inception to over 50,000 as of 2016.11 The proportion of female hospitalists increased from 31% in 2012 to 52% in 2014, reflecting equal gender representation in hospital medicine.12 Available evidence shows gender disparities exist in hospital medicine disproportionately affecting female hospitalists in their career advancement, including leadership and scholarship opportunities.13 However, there remains a knowledge gap regarding the prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment experienced by hospitalists.

Our study examines the experiences of academic hospitalists regarding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment and the impact of gender on career satisfaction and advancement.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

An online survey was developed and approved by the institutional board review (IRB) at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. University-based academic centers with hospitalist programs, identified through personal connections, from across the continental United Stated were identified as potential study sites, and leaders at each institution were contacted to ascertain potential participation in the survey. The survey was distributed to Internal Medicine hospitalists at 18 participating academic institutions from January 2019 to June 2019. Participation was voluntary. The cover letter explained the purpose of the study and provided a link to the survey. To maintain anonymity, none of the questionnaires requested identifying information from participants. A web-based Qualtrics online-based survey platform was used.

Survey Elements

The survey aimed to assess several elements of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment. All questions about these experiences distinguished encounters with patients from those with colleagues, and questions about occurrences either over a career or in the last 30 days were intended to capture both distant and recent timeframes. The theme for the questions for the survey was based on previous studies.4,7,8 The wording of questions was simplified to make them easily understandable, and the brevity of the survey was maintained to prevent possible nonresponses.14 Additional questions (mistaken for a healthcare provider other than a physician, feeling respected by patients and colleagues, referred to by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent), which were deemed relevant in day-to-day clinical practice through consensus among study investigators and discussions among peer hospitalists, were incorporated into the final survey (Appendix). Survey questions were intended to capture several elements regarding interactions with patients and with colleagues or other healthcare providers (HCPs).

Questions on gender-based discrimination included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] mistaken you for a healthcare provider other than a physician?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] asked you to do something not at your level of training?

- Do you feel respected? Do you perceive your gender has impacted opportunities for your career advancement?

Questions on sexual harassment included:

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] touched you inappropriately, made sexual remarks or gestures, or made suggestive looks?

- Has a patient [colleague or other healthcare provider] referred to you by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent?

In addition, the survey sought demographic information of the participants (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and information about their individual institutions (names and locations) (Appendix). The geographical locations of the institutions were further categorized into four different regions according to the United States Census Bureau (Northwest, Midwest, South, and West). At the end of the survey, participants were given an opportunity to provide any additional comments.

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive summary statistics were used for demographic data. Associations between the variables were analyzed using chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. The variations among institution-based responses were presented in the form of inter-quartile range (IQR). All tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics software version 24. Relevant responses representative of the overall respondents’ sentiments as provided under additional comment section were discussed and cited.

RESULTS

Eighteen different academic institutions across the United States participated in the study, with 336 individual responses. The majority of respondents were females (57%), in younger age categories (58% were 30-39 years old), Caucasian (59%), and early-career hospitalists (>50% working as hospitalists for ≤5 years) (Table 1). Regarding the overall geographic distribution, the largest number of responses were from the Midwest (n = 115; 35.6%) (Table 1 and Appendix).

Gender Discrimination

Interactions With Patients

Over their careers, 69% of hospitalists reported being mistaken for an HCP other than a physician by patients. This was more common among females than among males (99% vs 29%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Almost half (48%) reported this had occurred in the last 30 days, more frequently by females (76% vs 10%; P < .001).

Of responding hospitalists, 96% stated that, over their careers, they have been asked by patients to do something they did not consider to be at their level of training (eg, help get food or water, help with a bed pan), with a higher prevalence of such experiences among females than males (99% vs 93%, respectively; P = .004) (Table 2). Most (71%) said they had experienced this in the last 30 days, which was again more frequently reported by females (78% vs 62%; P = .001).

The responses from female hospitalists regarding their career-long experiences of being mistaken for an HCP or asked to do something not at their level of training by their patients had both the highest number of positive responses across institutions (median of hospital proportions, 100%) and the least institutional variation since both had the narrowest IQR) (Table 2).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Among hospitalists responding to the survey, 46% felt that, over their careers, they had been mistaken for nonphysician HCPs by colleagues or other HCPs. This was more prevalent among females than among males (65% vs 20%; P < .001) (Table 2). Among respondents, 14% reported these events had occurred in the last 30 days, which was again more common among females (21% vs 5%; P < .001).

Over their careers, 26% of hospitalists reported they have been asked by a colleague or HCP to do something not at their level of training (eg, clean up the physician’s work room, make coffee, take notes in a meeting), with similar prevalence among females and males (29% vs 23%; P = .228). Ten percent reported these occurrences in the last 30 days, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 9%; P = .330).

Feelings of Respect and Opportunities for Career Advancement

When asked to rate the statement “I feel respected by patients” on a 5-point Likert scale, female hospitalists overall scored significantly lower as compared with their male counterparts (mean score, 3.73 vs 4.04; P < .001) (Table 3); this was also true when asked about feelings of respect by physicians (mean score, 3.84 vs 4.15; P < .001). Female hospitalists were more likely than males to report that their gender has more negatively impacted their opportunities for career advancement (mean score, 2.73 vs 3.34; P < .001).

Sexual Harassment

Interactions With Patients

Over half (57%) of hospitalists reported career-long experiences of patient(s) touching them inappropriately, making sexual remarks or gestures, or making suggestive looks. These experiences were more prevalent among females than among males (72% vs 36%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Fifteen percent said they had such experience in rhe last 30 days, which was also more common among females (22% vs 6%; P < .001).

Most hospitalists (84%) reported that patients have referred to them by inappropriately familiar terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent over their careers, with females more frequently reporting these behaviors (95% vs 68%; P < .001). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 48%, which was again more common among females (68% vs 23%; P < .001).

Interactions With Colleagues or Other HCPs

Within their careers, 15% of hospitalists reported at least one experience of a colleague or HCP touching them inappropriately or making sexual remarks, gestures, or suggestive looks. This was more prevalent for females than males (18% vs 10%, respectively; P = .033). Only 2% of both females and males reported these experiences in the last 30 days (2% vs 2%; P = .981).

Almost one-third of participants (32%) affirmed that another HCP has referred to them by terms such as “honey,” “dear,” “sweetheart,” “sugar,” or equivalent in their career, with a higher proportion of females than males reporting these events (39% vs 23%; P = .002) (Table 2). Experiencing this during the last 30 days was reported by 10%, which was similar between females and males (12% vs 7%; P = .112).

Additional Comments From Respondents

- “Throughout my training and now into my professional career, there are nearly weekly incidents of elderly male patients referring to me as “honey/dear/sweetie” or even by my first name, even though I introduce myself as their physician and politely correct them. They will often refer to me as a nurse and ask me to do something not at my level of training. Sometimes even despite correcting the patient, they continue to refer to me as such. Throughout the years, other female MDs and I have discussed that this is ‘status quo’ for female physicians and observe that this is not an experience that male MDs share.”

- “I frequently round with a male nurse practitioner and the patients almost always, despite introducing ourselves and our roles, turn to him and ask him questions instead of addressing them to me.”

- “Our institution allows female faculty to be interviewed about childcare, household labor division, plans for pregnancy. One professor asks women private details about their private relationships such as what they do with spouse on date night or weekends away.”

- “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. I don’t think it’s unreasonable for people to ask me to do things, no matter my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.”

DISCUSSION

This survey demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common, both in more distant and recent time frames. Notably, these experiences are shared by female and male physicians in interactions with both patients and colleagues, though male hospitalists report most of these experiences at significantly lower frequencies than females. These results support past work showing that female physicians are significantly more likely to be subjected to gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, but also challenges the perception that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment are uniquely experienced by females.

A startling number of females and males in the study reported sexual harassment (inappropriate touching, remarks, gestures, and looks) when interacting with patients throughout their careers and in last 30 days. Many males and females reported that patients had referred to them with inappropriately familiar, and potentially demeaning, terms of endearment. For both overt and implicit sexual harassment, females were significantly more likely than males to report experiencing these behaviors when interacting with patients. Although some of these experiences may seem less harmful than others, a meta-analysis demonstrated that frequent, less intense experiences of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have a similar impact on female’s well-being as do less frequent, more intense experiences.15 Although the person using the terms of endearment like “honey,” “sugar,” or “sweetheart” may feel the terms are harmless, such expressions can be inappropriate and constitute sexual harassment according to the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Civil Rights.16 The Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP) also classifies such terms into verbal categories of sexual harrassment.17

Of female physicians surveyed, 99% reported that they had been mistaken for HCPs other than physicians by their patients over their careers. Although this was also reported by male physicians, the experience was 3.4 times as likely for female physicians. Misidentification by patients may represent a disconnect between the growing female representation in the physician workforce and patients’ conceptions of the traditional image of a physician.

In parallel with this finding of misidentification, an interesting area of the study was the question regarding being asked to do “something not at your level of training.” A recurring theme in the comments was a rejection of the notion that certain tasks were “beneath a level of training,” suggesting a common view that acts of caregiving are not bounded by hierarchy. Analysis of qualitative responses showed that 40% of these responses had comments regarding this question. An example was “It’s hard to answer questions related to my level of training. . . . I don’t think being a doctor means that I am above this, or that it is inappropriate to be asked to do this.” Notably, however, a larger number of female than male physicians responded yes to this question in both study time frames. This points to a differential in how female physicians are viewed by patients, both in frequent misidentification and in behaviors more frequently asked of female physicians than their male counterparts. Given the comments, it may also suggest a difference in how female and male physicians perceive the fluidity of bounds on their care-taking roles set by their “level of training.”

A large number of study participants were early-career hospitalists, which may in part explain some of the study results. In a previous study of gender equity in an Internal Medicine department, physicians practicing medicine for more than 15 years perceived the departmental culture as more favorable than physicians with shorter careers.10 Additionally, the perception of cultures was most discordant between senior male physicians and junior female physicians.10 Because many hospitalists are early-career physicians, they may have trained in an environment that had heightened awareness surrounding gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, which affects the overall study results.

Multiple qualitative comments, mentioned above, were submitted by participants describing their experiences in all categories. Such comments paint a picture of insidious bias and cultural norms affecting the quality of female physicians’ work lives.

Two questions focused on career satisfaction and the sense of respect from patients and colleagues. In both responses, there was a statistically different response between males and females, with females less likely to report that they felt respected and that their gender adversely impacted their opportunities for career advancement. This is disturbing information and warrants more investigation.

The reasons for the observed prevalence of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in this broad survey of academic hospitalists are uncertain. Multiple studies to date have demonstrated that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment have historically existed in medicine and continue to even today. Unlike physicians with long-term relationships with patients, hospitalists may face more exposure due to a lack of long-term continuity with patients. The absence of an established trust in the relationship also may make them more vulnerable to inappropriate behaviors when interacting with patients. Hospital medicine, however, is a young specialty with equal gender representation and should be at the forefront of addressing and solving these issues of gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment.

The survey had a good distribution between female and male participants. Additionally, the survey reflected the general distribution of the national hospitalist workforce in gender, age, and ethnic/racial distribution, as well as number of years in practice.12 The study surveyed respondents regarding experiences in both long- and short-term time frames, as well as experiences with patients and colleagues.

Our study reflects a cross-sectional snapshot of hospitalists’ perceptions with no longitudinal follow-up. Since the survey was limited to academic medical centers, it may not reflect experiences in community/private practice settings. The small number of participants limited the ability to perform subgroup analyses by age, race, or years in practice, which may play a role in interactions with patients and colleagues. Since the number of respondents varied greatly by institution, a minority of institutions could have influenced some of the findings. Narrow IQRs of the hospital proportions as shown in Table 2 would suggest similar responses across institutions, whereas wide IQRs would suggest that a smaller number of institutions were possibly driving the findings. Because of the survey distribution method, it is unknown how many physicians received the survey and a response rate could not be calculated. Further, selection, recall, and detection biases cannot be ruled out.

CONCLUSION

This survey shows that gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment in the academic hospitalist healthcare environment are common and more frequently experienced by female physicians, both in interactions with patients and colleagues. Our study highlights the need to address this prevalent issue among academic hospitalists.

1. WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health. A training manual for health managers. World Health Organization; 2001. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/RHR_01_29/en/

2. Sexual Harassment. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed Jan 5, 2020. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm

3. Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(4):352-358. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.4.352

4. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):889-96. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00007

5. Bates CK, Jagsi R, Gordon LK, et al. It is time for zero tolerance for sexual harassment in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):163-165. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002050

6. Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1589-1591. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1809846

7. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2188

8. Phillips SP, Schneider MS. Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1936-1939. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199312233292607

9. Kane L. Sexual Harassment of Physicians: Report 2018. Medscape. June 13, 2018. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/sexual-harassment-of-physicians-6010304

10. Ruzycki SM, Freeman G, Bharwani A, Brown A. Association of physician characteristics with perceptions and experiences of gender equity in an academic internal medicine department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915165. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15165

11. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

12. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

13. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

14. Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D; iConnect consortium. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62

15 Sojo VE, Wood RE, Genat AE. Harmful Workplace Experiences and Women’s Occupational Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(1):10-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346

16. Office of Civil Rights: Sexual Harassment. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/Sexual-Harassment

17. Sexual Harassment: Categories of Sexual Harassment. Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP). Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.sexualassault.army.mil/categories_of_harassment.aspx

1. WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Transforming health systems: gender and rights in reproductive health. A training manual for health managers. World Health Organization; 2001. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/gender_rights/RHR_01_29/en/

2. Sexual Harassment. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed Jan 5, 2020. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm

3. Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(4):352-358. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.4.352

4. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):889-96. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00007

5. Bates CK, Jagsi R, Gordon LK, et al. It is time for zero tolerance for sexual harassment in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):163-165. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002050

6. Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1589-1591. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1809846

7. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2188

8. Phillips SP, Schneider MS. Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1936-1939. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199312233292607

9. Kane L. Sexual Harassment of Physicians: Report 2018. Medscape. June 13, 2018. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/sexual-harassment-of-physicians-6010304

10. Ruzycki SM, Freeman G, Bharwani A, Brown A. Association of physician characteristics with perceptions and experiences of gender equity in an academic internal medicine department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915165. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15165

11. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

12. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

13. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

14. Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D; iConnect consortium. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62

15 Sojo VE, Wood RE, Genat AE. Harmful Workplace Experiences and Women’s Occupational Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(1):10-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346

16. Office of Civil Rights: Sexual Harassment. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/Sexual-Harassment

17. Sexual Harassment: Categories of Sexual Harassment. Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program (SHARP). Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.sexualassault.army.mil/categories_of_harassment.aspx

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital medicine and perioperative care: A framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care

Of the 36 million US hospitalizations each year, 22% are surgical.1 Although less frequent than medical hospitalizations, surgical hospitalizations are more than twice as costly.2 Additionally, surgical hospitalizations are on average longer than medical hospitalizations.2 Given the increased scrutiny on cost and efficiency of care, attention has turned to optimizing perioperative care. Hospitalists are well positioned to provide specific expertise in the complex interdisciplinary medical management of surgical patients.

In recent decades, multiple models of hospitalist involvement in perioperative care have evolved across the United States.3-19 To consolidate knowledge and experience and to develop a framework for providing the best care for surgical patients, the Society of Hospital Medicine organized the Perioperative Care Work Group in 2015. This framework was designed for interdisciplinary collaboration in building and strengthening perioperative care programs.

METHODS

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognized hospital medicine programs’ need for guidance in developing collaborative care in perioperative medicine and appointed the Perioperative Care Work Group in May 2015. Work group members are perioperative medicine experts from US medical centers. They have extensive knowledge of the literature as well as administrative and clinical experience in a variety of perioperative care models.

Topic Development. Initial work was focused on reviewing and discussing multiple models of perioperative care and exploring the roles that hospital medicine physicians have within these models. Useful information was summarized to guide hospitals and physicians in designing, implementing, and expanding patient-centric perioperative medicine services with a focus on preoperative and postoperative care. A final document was created; it outlines system-level issues in perioperative care, organized by perioperative phases.

Initial Framework. Group members submitted written descriptions of key issues in each of 4 phases: (1) preoperative, (2) day of surgery, (3) postoperative inpatient, and (4) postdischarge. These descriptions were merged and reviewed by the content experts. Editing and discussion from the entire group were incorporated into the final matrix, which highlighted (1) perioperative phase definitions, (2) requirements for patients to move to next phase, (3) elements of care coordination typically provided by surgery, anesthesiology, and medicine disciplines, (4) concerns and risks particular to each phase, (5) unique considerations for each phase, (6) suggested metrics of success, and (7) key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care in an institution. All members provided final evaluation and editing.

Final Approval. The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries (PCMIS) was presented to the board of the Society of Hospital Medicine in fall 2015 and was approved for use in centering and directing discussions regarding perioperative care.

Models of Care. The Perioperative Care Work Group surveyed examples of hospitalist engagement in perioperative care and synthesized these into synopses of existing models of care for the preoperative, day-of-surgery, postoperative-inpatient, and postdischarge phases.

RESULTS

Defining Key Concepts and Issues

Hospitalists have participated in a variety of perioperative roles for more than a decade. Roles include performing in-depth preoperative assessments, providing oversight to presurgical advanced practice provider assessments, providing inpatient comanagement and consultation both before and after surgery, and providing postdischarge follow-up within the surgical period for medical comorbidities.

Although a comprehensive look at the entire perioperative period is important, 4 specific phases were defined to guide this work (Figure). The phases identified were based on time relative to surgery, with unique considerations as to the overall perioperative period. Concerns and potential risks specific to each phase were considered (Table 1).

The PCMIS was constructed to provide a single coherent vision of key concepts in perioperative care (Table 2). Also identified were several key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care within an institution (Table 3).

Models of Care

Multiple examples of hospitalist involvement were collected to inform the program development guidelines. The specifics noted among the reviewed practice models are described here.

Preoperative. In some centers, all patients scheduled for surgery are required to undergo evaluation at the institution’s preoperative clinic. At most others, referral to the preoperative clinic is at the discretion of the surgical specialists, who have been informed of the clinic’s available resources. Factors determining whether a patient has an in-person clinic visit, undergoes a telephone-based medical evaluation, or has a referral deferred to the primary care physician (PCP) include patient complexity and surgery-specific risk. Patients who have major medical comorbidities (eg, chronic lung or heart disease) or are undergoing higher risk procedures (eg, those lasting >1 hour, laparotomy) most often undergo a formal clinic evaluation. Often, even for a patient whose preoperative evaluation is completed by a PCP, the preoperative nursing staff will call before surgery to provide instructions and to confirm that preoperative planning is complete. Confirmation includes ensuring that the surgery consent and preoperative history and physical examination documents are in the medical record, and that all recommended tests have been performed. If deficiencies are found, surgical and preoperative clinic staff are notified.