User login

Hospital medicine and perioperative care: A framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care

Of the 36 million US hospitalizations each year, 22% are surgical.1 Although less frequent than medical hospitalizations, surgical hospitalizations are more than twice as costly.2 Additionally, surgical hospitalizations are on average longer than medical hospitalizations.2 Given the increased scrutiny on cost and efficiency of care, attention has turned to optimizing perioperative care. Hospitalists are well positioned to provide specific expertise in the complex interdisciplinary medical management of surgical patients.

In recent decades, multiple models of hospitalist involvement in perioperative care have evolved across the United States.3-19 To consolidate knowledge and experience and to develop a framework for providing the best care for surgical patients, the Society of Hospital Medicine organized the Perioperative Care Work Group in 2015. This framework was designed for interdisciplinary collaboration in building and strengthening perioperative care programs.

METHODS

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognized hospital medicine programs’ need for guidance in developing collaborative care in perioperative medicine and appointed the Perioperative Care Work Group in May 2015. Work group members are perioperative medicine experts from US medical centers. They have extensive knowledge of the literature as well as administrative and clinical experience in a variety of perioperative care models.

Topic Development. Initial work was focused on reviewing and discussing multiple models of perioperative care and exploring the roles that hospital medicine physicians have within these models. Useful information was summarized to guide hospitals and physicians in designing, implementing, and expanding patient-centric perioperative medicine services with a focus on preoperative and postoperative care. A final document was created; it outlines system-level issues in perioperative care, organized by perioperative phases.

Initial Framework. Group members submitted written descriptions of key issues in each of 4 phases: (1) preoperative, (2) day of surgery, (3) postoperative inpatient, and (4) postdischarge. These descriptions were merged and reviewed by the content experts. Editing and discussion from the entire group were incorporated into the final matrix, which highlighted (1) perioperative phase definitions, (2) requirements for patients to move to next phase, (3) elements of care coordination typically provided by surgery, anesthesiology, and medicine disciplines, (4) concerns and risks particular to each phase, (5) unique considerations for each phase, (6) suggested metrics of success, and (7) key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care in an institution. All members provided final evaluation and editing.

Final Approval. The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries (PCMIS) was presented to the board of the Society of Hospital Medicine in fall 2015 and was approved for use in centering and directing discussions regarding perioperative care.

Models of Care. The Perioperative Care Work Group surveyed examples of hospitalist engagement in perioperative care and synthesized these into synopses of existing models of care for the preoperative, day-of-surgery, postoperative-inpatient, and postdischarge phases.

RESULTS

Defining Key Concepts and Issues

Hospitalists have participated in a variety of perioperative roles for more than a decade. Roles include performing in-depth preoperative assessments, providing oversight to presurgical advanced practice provider assessments, providing inpatient comanagement and consultation both before and after surgery, and providing postdischarge follow-up within the surgical period for medical comorbidities.

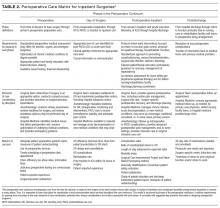

Although a comprehensive look at the entire perioperative period is important, 4 specific phases were defined to guide this work (Figure). The phases identified were based on time relative to surgery, with unique considerations as to the overall perioperative period. Concerns and potential risks specific to each phase were considered (Table 1).

The PCMIS was constructed to provide a single coherent vision of key concepts in perioperative care (Table 2). Also identified were several key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care within an institution (Table 3).

Models of Care

Multiple examples of hospitalist involvement were collected to inform the program development guidelines. The specifics noted among the reviewed practice models are described here.

Preoperative. In some centers, all patients scheduled for surgery are required to undergo evaluation at the institution’s preoperative clinic. At most others, referral to the preoperative clinic is at the discretion of the surgical specialists, who have been informed of the clinic’s available resources. Factors determining whether a patient has an in-person clinic visit, undergoes a telephone-based medical evaluation, or has a referral deferred to the primary care physician (PCP) include patient complexity and surgery-specific risk. Patients who have major medical comorbidities (eg, chronic lung or heart disease) or are undergoing higher risk procedures (eg, those lasting >1 hour, laparotomy) most often undergo a formal clinic evaluation. Often, even for a patient whose preoperative evaluation is completed by a PCP, the preoperative nursing staff will call before surgery to provide instructions and to confirm that preoperative planning is complete. Confirmation includes ensuring that the surgery consent and preoperative history and physical examination documents are in the medical record, and that all recommended tests have been performed. If deficiencies are found, surgical and preoperative clinic staff are notified.

During a typical preoperative clinic visit, nursing staff complete necessary regulatory documentation requirements and ensure that all items on the preoperative checklist are completed before day of surgery. Nurses or pharmacists perform complete medication reconciliation. For medical evaluation at institutions with a multidisciplinary preoperative clinic, patients are triaged according to comorbidity and procedure. These clinics often have anesthesiology and hospital medicine clinicians collaborating with interdisciplinary colleagues and with patients’ longitudinal care providers (eg, PCP, cardiologist). Hospitalists evaluate patients with comorbid medical diseases and address uncontrolled conditions and newly identified symptomatology. Additional testing is determined by evidence- and guideline-based standards. Patients receive preoperative education, including simple template-based medication management instructions. Perioperative clinicians follow up on test results, adjust therapy, and counsel patients to optimize health in preparation for surgery.

Patients who present to the hospital and require urgent surgical intervention are most often admitted to the surgical service, and hospital medicine provides timely consultation for preoperative recommendations. At some institutions, protocols may dictate that certain surgical patients (eg, elderly with hip fracture) are admitted to the hospital medicine service. In these scenarios, the hospitalist serves as the primary inpatient care provider and ensures preoperative medical optimization and coordination with the surgical service to expedite plans for surgery.

Day of Surgery. On the day of surgery, the surgical team verifies all patient demographic and clinical information, confirms that all necessary documentation is complete (eg, consents, history, physical examination), and marks the surgical site. The anesthesia team performs a focused review and examination while explaining the perioperative care plan to the patient. Most often, the preoperative history and physical examination, completed by a preoperative clinic provider or the patient’s PCP, is used by the anesthesiologist as the basis for clinical assessment. However, when information is incomplete or contradictory, surgery may be delayed for further record review and consultation.

Hospital medicine teams may be called to the pre-anesthesia holding area to evaluate acute medical problems (eg, hypertension, hyperglycemia, new-onset arrhythmia) or to give a second opinion in cases in which the anesthesiologist disagrees with the recommendations made by the provider who completed the preoperative evaluation. In either scenario, hospitalists must provide rapid service in close collaboration with anesthesiologists and surgeons. If a patient is found to be sufficiently optimized for surgery, the hospitalist clearly documents the evaluation and recommendation in the medical record. For a patient who requires further medical intervention before surgery, the hospitalist often coordinates the immediate disposition (eg, hospital admission or discharge home) and plans for optimization in the timeliest manner possible.

Occasionally, hospitalists are called to evaluate a patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for a new or chronic medical problem before the patient is transitioned to the next level of care. At most institutions, all PACU care is provided under the direction of anesthesiology, so it is imperative to collaborate with the patient’s anesthesiologist for all recommendations. When a patient is to be discharged home, the hospitalist coordinates outpatient follow-up plans for any medical issues to be addressed postoperatively. Hospitalists also apply their knowledge of the limitations of non–intensive care unit hospital care to decisions regarding appropriate triage of patients being admitted after surgery.

Postoperative Inpatient. Hospitalists provide a 24/7 model of care that deploys a staff physician for prompt assessment and management of medical problems in surgical patients. This care can be provided as part of the duties of a standard hospital medicine team or can be delivered by a dedicated perioperative medical consultation and comanagement service. In either situation, the type of medical care, comanagement or consultation, is determined at the outset. As consultants, hospitalists provide recommendations for medical care but do not write orders or take primary responsibility for management. Comanagement agreements are common, especially for orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery; these agreements delineate the specific circumstances and responsibilities of the hospitalist and surgical teams. Indications for comanagement, which may be identified during preoperative clinic evaluation or on admission, include uncontrolled or multiple medical comorbidities or the development of nonsurgical complications in the perioperative period. In the comanagement model, care of most medical issues is provided at the discretion of the hospitalist. Although this care includes order-writing privileges, management of analgesics, wounds, blood products, and antithrombotics is usually reserved for the surgical team, with the hospitalist only providing recommendations. In some circumstances, hospitalists may determine that the patient’s care requires consultation with other specialists. Although it is useful for the hospitalist to speak directly with other consultants and coordinate their recommendations, the surgical service should agree to the involvement of other services.

In addition to providing medical care throughout a patient’s hospitalization, the hospitalist consultant is crucial in the discharge process. During the admission, ideally in collaboration with a pharmacist, the hospitalist reviews the home medications and may change chronic medications. The hospitalist may also identify specific postdischarge needs of which the surgical team is not fully aware. These medical plans are incorporated through shared responsibility for discharge orders or through a reliable mechanism for ensuring the surgical team assumes responsibility. Final medication reconciliation at discharge, and a plan for prior and new medications, can be formulated with pharmacy assistance. Finally, the hospitalist is responsible for coordinating medically related hospital follow-up and handover back to the patient’s longitudinal care providers. The latter occurs through inclusion of medical care plans in the discharge summary completed by the surgical service and, in complex cases, through direct communication with the patient’s outpatient providers.

For some patients, medical problems eclipse surgical care as the primary focus of management. Collaborative discussion between the medical and surgical teams helps determine if it is more appropriate for the medical team to become the primary service, with the surgical team consulting. Such triage decisions should be jointly made by the attending physicians of the services rather than by intermediaries.

Postdischarge. Similar to their being used for medical problems after hospitalization, hospitalist-led postdischarge and extensivist clinics may be used for rapid follow-up of medical concerns in patients discharged after surgical admissions. A key benefit of this model is increased availability over what primary care clinics may be able to provide on short notice, particularly for patients who previously did not have a PCP. Additionally, the handover of specific follow-up items is more streamlined because the transition of care is between hospitalists from the same institution. Through the postdischarge clinic, hospitalists can provide care through either clinic visits or telephone-based follow-up. Once a patient’s immediate postoperative medical issues are fully stabilized, the patient can be transitioned to long-term primary care follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The United States is focused on sensible, high-value care. Perioperative care is burgeoning with opportunities for improvement, including reducing avoidable complications, developing systems for early recognition and treatment of complications, and streamlining processes to shorten length of stay and improve patient experience. The PCMIS provides the needed platform to catalyze detailed collaborative work between disciplines engaged in perioperative care.

As average age and level of medical comorbidity increase among surgical patients, hospitalists will increasingly be called on to assist in perioperative care. Hospitalists have long been involved in caring for medically complex surgical patients, through comanagement, consultation, and preoperative evaluations. As a provider group, hospitalists have comprehensive skills in quality and systems improvement, and in program development across hospital systems nationwide. Hospitalists have demonstrated their value by focusing on improving patient outcomes and enhancing patient engagement and experiences. Additionally, the perioperative period is fraught with multiple and complicated handoffs, a problem area for which hospital medicine has pioneered solutions and developed unique expertise. Hospital medicine is well prepared to provide skilled and proven leadership in the timely development, improvement, and expansion of perioperative care for this increasingly older and chronically ill population.

Hospitalists are established in multiple perioperative roles for high-risk surgical patients and have the opportunity to expand optimal patient-centric perioperative care systems working in close concert with surgeons and anesthesiologists. The basics of developing these systems include (1) assessing risk for medical complications, (2) planning for perioperative care, (3) developing programs aimed at risk reduction for preventable complications and early identification and intervention for unavoidable complications, and (4) guiding quality improvement efforts, including planning for frequent handoffs and transitions.

As a key partner in developing comprehensive programs in perioperative care, hospital medicine will continue to shape the future of hospital care for all patients. The PCMIS, as developed with support from the Society of Hospital Medicine, will aid efforts to achieve the best perioperative care models for our surgical patients.

Disclosures

Financial activities outside the submitted work: Drs. Pfeifer and Jaffer report payment for development of educational presentations; Dr. Grant reports payment for expert testimony pertaining to hospital medicine; Drs. Grant and Jaffer report royalties from publishing; Drs. Thompson, Pfiefer, Grant, Slawski, and Jaffer report travel expenses for speaking and serving on national committees; and Drs. Slawski and Jaffer serve on the board of the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement. The other authors have nothing to report.

1. Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 (Current Population Reports, P25-1143). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Steiner C, Andrews R, Barrett M, Weiss A. HCUP Projections: Cost of Inpatient Discharges 2003 to 2013 (Rep 2013-01). Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/projections/2013-01.pdf. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed May 26, 2016.

3. Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Cheng HQ, et al. Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2004-2010. PubMed

4. Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219-225. PubMed

5. Carr AM, Irigoyen M, Wimmer RS, Arbeter AM. A pediatric residency experience with surgical co-management. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):144-148. PubMed

6. Della Rocca GJ, Moylan KC, Crist BD, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Mehr DR. Comanagement of geriatric patients with hip fractures: a retrospective, controlled, cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2013;4(1):10-15. PubMed

7. Fisher AA, Davis MW, Rubenach SE, Sivakumaran S, Smith PN, Budge MM. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(3):172-178. PubMed

8. Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Kates SL, McCann RM. Geriatric co-management of proximal femur fractures: total quality management and protocol-driven care result in better outcomes for a frail patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1349-1356. PubMed

9. Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al; Hospitalist-Orthopedic Team Trial Investigators. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38. PubMed

10. Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. Principles of comanagement and the geriatric fracture center. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):183-189. PubMed

11. Merli GJ. The hospitalist joins the surgical team. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):67-69. PubMed

12. Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):796-801. PubMed

13. Pinzur MS, Gurza E, Kristopaitis T, et al. Hospitalist-orthopedic co-management of high-risk patients undergoing lower extremity reconstruction surgery. Orthopedics. 2009;32(7):495. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Rappaport DI, Cerra S, Hossain J, Sharif I, Pressel DM. Pediatric hospitalist preoperative evaluation of children with neuromuscular scoliosis. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(12):684-688. PubMed

16. Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31. PubMed

17. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368. PubMed

18. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

19. Whinney C, Michota F. Surgical comanagement: a natural evolution of hospitalist practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):394-397. PubMed

Of the 36 million US hospitalizations each year, 22% are surgical.1 Although less frequent than medical hospitalizations, surgical hospitalizations are more than twice as costly.2 Additionally, surgical hospitalizations are on average longer than medical hospitalizations.2 Given the increased scrutiny on cost and efficiency of care, attention has turned to optimizing perioperative care. Hospitalists are well positioned to provide specific expertise in the complex interdisciplinary medical management of surgical patients.

In recent decades, multiple models of hospitalist involvement in perioperative care have evolved across the United States.3-19 To consolidate knowledge and experience and to develop a framework for providing the best care for surgical patients, the Society of Hospital Medicine organized the Perioperative Care Work Group in 2015. This framework was designed for interdisciplinary collaboration in building and strengthening perioperative care programs.

METHODS

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognized hospital medicine programs’ need for guidance in developing collaborative care in perioperative medicine and appointed the Perioperative Care Work Group in May 2015. Work group members are perioperative medicine experts from US medical centers. They have extensive knowledge of the literature as well as administrative and clinical experience in a variety of perioperative care models.

Topic Development. Initial work was focused on reviewing and discussing multiple models of perioperative care and exploring the roles that hospital medicine physicians have within these models. Useful information was summarized to guide hospitals and physicians in designing, implementing, and expanding patient-centric perioperative medicine services with a focus on preoperative and postoperative care. A final document was created; it outlines system-level issues in perioperative care, organized by perioperative phases.

Initial Framework. Group members submitted written descriptions of key issues in each of 4 phases: (1) preoperative, (2) day of surgery, (3) postoperative inpatient, and (4) postdischarge. These descriptions were merged and reviewed by the content experts. Editing and discussion from the entire group were incorporated into the final matrix, which highlighted (1) perioperative phase definitions, (2) requirements for patients to move to next phase, (3) elements of care coordination typically provided by surgery, anesthesiology, and medicine disciplines, (4) concerns and risks particular to each phase, (5) unique considerations for each phase, (6) suggested metrics of success, and (7) key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care in an institution. All members provided final evaluation and editing.

Final Approval. The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries (PCMIS) was presented to the board of the Society of Hospital Medicine in fall 2015 and was approved for use in centering and directing discussions regarding perioperative care.

Models of Care. The Perioperative Care Work Group surveyed examples of hospitalist engagement in perioperative care and synthesized these into synopses of existing models of care for the preoperative, day-of-surgery, postoperative-inpatient, and postdischarge phases.

RESULTS

Defining Key Concepts and Issues

Hospitalists have participated in a variety of perioperative roles for more than a decade. Roles include performing in-depth preoperative assessments, providing oversight to presurgical advanced practice provider assessments, providing inpatient comanagement and consultation both before and after surgery, and providing postdischarge follow-up within the surgical period for medical comorbidities.

Although a comprehensive look at the entire perioperative period is important, 4 specific phases were defined to guide this work (Figure). The phases identified were based on time relative to surgery, with unique considerations as to the overall perioperative period. Concerns and potential risks specific to each phase were considered (Table 1).

The PCMIS was constructed to provide a single coherent vision of key concepts in perioperative care (Table 2). Also identified were several key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care within an institution (Table 3).

Models of Care

Multiple examples of hospitalist involvement were collected to inform the program development guidelines. The specifics noted among the reviewed practice models are described here.

Preoperative. In some centers, all patients scheduled for surgery are required to undergo evaluation at the institution’s preoperative clinic. At most others, referral to the preoperative clinic is at the discretion of the surgical specialists, who have been informed of the clinic’s available resources. Factors determining whether a patient has an in-person clinic visit, undergoes a telephone-based medical evaluation, or has a referral deferred to the primary care physician (PCP) include patient complexity and surgery-specific risk. Patients who have major medical comorbidities (eg, chronic lung or heart disease) or are undergoing higher risk procedures (eg, those lasting >1 hour, laparotomy) most often undergo a formal clinic evaluation. Often, even for a patient whose preoperative evaluation is completed by a PCP, the preoperative nursing staff will call before surgery to provide instructions and to confirm that preoperative planning is complete. Confirmation includes ensuring that the surgery consent and preoperative history and physical examination documents are in the medical record, and that all recommended tests have been performed. If deficiencies are found, surgical and preoperative clinic staff are notified.

During a typical preoperative clinic visit, nursing staff complete necessary regulatory documentation requirements and ensure that all items on the preoperative checklist are completed before day of surgery. Nurses or pharmacists perform complete medication reconciliation. For medical evaluation at institutions with a multidisciplinary preoperative clinic, patients are triaged according to comorbidity and procedure. These clinics often have anesthesiology and hospital medicine clinicians collaborating with interdisciplinary colleagues and with patients’ longitudinal care providers (eg, PCP, cardiologist). Hospitalists evaluate patients with comorbid medical diseases and address uncontrolled conditions and newly identified symptomatology. Additional testing is determined by evidence- and guideline-based standards. Patients receive preoperative education, including simple template-based medication management instructions. Perioperative clinicians follow up on test results, adjust therapy, and counsel patients to optimize health in preparation for surgery.

Patients who present to the hospital and require urgent surgical intervention are most often admitted to the surgical service, and hospital medicine provides timely consultation for preoperative recommendations. At some institutions, protocols may dictate that certain surgical patients (eg, elderly with hip fracture) are admitted to the hospital medicine service. In these scenarios, the hospitalist serves as the primary inpatient care provider and ensures preoperative medical optimization and coordination with the surgical service to expedite plans for surgery.

Day of Surgery. On the day of surgery, the surgical team verifies all patient demographic and clinical information, confirms that all necessary documentation is complete (eg, consents, history, physical examination), and marks the surgical site. The anesthesia team performs a focused review and examination while explaining the perioperative care plan to the patient. Most often, the preoperative history and physical examination, completed by a preoperative clinic provider or the patient’s PCP, is used by the anesthesiologist as the basis for clinical assessment. However, when information is incomplete or contradictory, surgery may be delayed for further record review and consultation.

Hospital medicine teams may be called to the pre-anesthesia holding area to evaluate acute medical problems (eg, hypertension, hyperglycemia, new-onset arrhythmia) or to give a second opinion in cases in which the anesthesiologist disagrees with the recommendations made by the provider who completed the preoperative evaluation. In either scenario, hospitalists must provide rapid service in close collaboration with anesthesiologists and surgeons. If a patient is found to be sufficiently optimized for surgery, the hospitalist clearly documents the evaluation and recommendation in the medical record. For a patient who requires further medical intervention before surgery, the hospitalist often coordinates the immediate disposition (eg, hospital admission or discharge home) and plans for optimization in the timeliest manner possible.

Occasionally, hospitalists are called to evaluate a patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for a new or chronic medical problem before the patient is transitioned to the next level of care. At most institutions, all PACU care is provided under the direction of anesthesiology, so it is imperative to collaborate with the patient’s anesthesiologist for all recommendations. When a patient is to be discharged home, the hospitalist coordinates outpatient follow-up plans for any medical issues to be addressed postoperatively. Hospitalists also apply their knowledge of the limitations of non–intensive care unit hospital care to decisions regarding appropriate triage of patients being admitted after surgery.

Postoperative Inpatient. Hospitalists provide a 24/7 model of care that deploys a staff physician for prompt assessment and management of medical problems in surgical patients. This care can be provided as part of the duties of a standard hospital medicine team or can be delivered by a dedicated perioperative medical consultation and comanagement service. In either situation, the type of medical care, comanagement or consultation, is determined at the outset. As consultants, hospitalists provide recommendations for medical care but do not write orders or take primary responsibility for management. Comanagement agreements are common, especially for orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery; these agreements delineate the specific circumstances and responsibilities of the hospitalist and surgical teams. Indications for comanagement, which may be identified during preoperative clinic evaluation or on admission, include uncontrolled or multiple medical comorbidities or the development of nonsurgical complications in the perioperative period. In the comanagement model, care of most medical issues is provided at the discretion of the hospitalist. Although this care includes order-writing privileges, management of analgesics, wounds, blood products, and antithrombotics is usually reserved for the surgical team, with the hospitalist only providing recommendations. In some circumstances, hospitalists may determine that the patient’s care requires consultation with other specialists. Although it is useful for the hospitalist to speak directly with other consultants and coordinate their recommendations, the surgical service should agree to the involvement of other services.

In addition to providing medical care throughout a patient’s hospitalization, the hospitalist consultant is crucial in the discharge process. During the admission, ideally in collaboration with a pharmacist, the hospitalist reviews the home medications and may change chronic medications. The hospitalist may also identify specific postdischarge needs of which the surgical team is not fully aware. These medical plans are incorporated through shared responsibility for discharge orders or through a reliable mechanism for ensuring the surgical team assumes responsibility. Final medication reconciliation at discharge, and a plan for prior and new medications, can be formulated with pharmacy assistance. Finally, the hospitalist is responsible for coordinating medically related hospital follow-up and handover back to the patient’s longitudinal care providers. The latter occurs through inclusion of medical care plans in the discharge summary completed by the surgical service and, in complex cases, through direct communication with the patient’s outpatient providers.

For some patients, medical problems eclipse surgical care as the primary focus of management. Collaborative discussion between the medical and surgical teams helps determine if it is more appropriate for the medical team to become the primary service, with the surgical team consulting. Such triage decisions should be jointly made by the attending physicians of the services rather than by intermediaries.

Postdischarge. Similar to their being used for medical problems after hospitalization, hospitalist-led postdischarge and extensivist clinics may be used for rapid follow-up of medical concerns in patients discharged after surgical admissions. A key benefit of this model is increased availability over what primary care clinics may be able to provide on short notice, particularly for patients who previously did not have a PCP. Additionally, the handover of specific follow-up items is more streamlined because the transition of care is between hospitalists from the same institution. Through the postdischarge clinic, hospitalists can provide care through either clinic visits or telephone-based follow-up. Once a patient’s immediate postoperative medical issues are fully stabilized, the patient can be transitioned to long-term primary care follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The United States is focused on sensible, high-value care. Perioperative care is burgeoning with opportunities for improvement, including reducing avoidable complications, developing systems for early recognition and treatment of complications, and streamlining processes to shorten length of stay and improve patient experience. The PCMIS provides the needed platform to catalyze detailed collaborative work between disciplines engaged in perioperative care.

As average age and level of medical comorbidity increase among surgical patients, hospitalists will increasingly be called on to assist in perioperative care. Hospitalists have long been involved in caring for medically complex surgical patients, through comanagement, consultation, and preoperative evaluations. As a provider group, hospitalists have comprehensive skills in quality and systems improvement, and in program development across hospital systems nationwide. Hospitalists have demonstrated their value by focusing on improving patient outcomes and enhancing patient engagement and experiences. Additionally, the perioperative period is fraught with multiple and complicated handoffs, a problem area for which hospital medicine has pioneered solutions and developed unique expertise. Hospital medicine is well prepared to provide skilled and proven leadership in the timely development, improvement, and expansion of perioperative care for this increasingly older and chronically ill population.

Hospitalists are established in multiple perioperative roles for high-risk surgical patients and have the opportunity to expand optimal patient-centric perioperative care systems working in close concert with surgeons and anesthesiologists. The basics of developing these systems include (1) assessing risk for medical complications, (2) planning for perioperative care, (3) developing programs aimed at risk reduction for preventable complications and early identification and intervention for unavoidable complications, and (4) guiding quality improvement efforts, including planning for frequent handoffs and transitions.

As a key partner in developing comprehensive programs in perioperative care, hospital medicine will continue to shape the future of hospital care for all patients. The PCMIS, as developed with support from the Society of Hospital Medicine, will aid efforts to achieve the best perioperative care models for our surgical patients.

Disclosures

Financial activities outside the submitted work: Drs. Pfeifer and Jaffer report payment for development of educational presentations; Dr. Grant reports payment for expert testimony pertaining to hospital medicine; Drs. Grant and Jaffer report royalties from publishing; Drs. Thompson, Pfiefer, Grant, Slawski, and Jaffer report travel expenses for speaking and serving on national committees; and Drs. Slawski and Jaffer serve on the board of the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement. The other authors have nothing to report.

Of the 36 million US hospitalizations each year, 22% are surgical.1 Although less frequent than medical hospitalizations, surgical hospitalizations are more than twice as costly.2 Additionally, surgical hospitalizations are on average longer than medical hospitalizations.2 Given the increased scrutiny on cost and efficiency of care, attention has turned to optimizing perioperative care. Hospitalists are well positioned to provide specific expertise in the complex interdisciplinary medical management of surgical patients.

In recent decades, multiple models of hospitalist involvement in perioperative care have evolved across the United States.3-19 To consolidate knowledge and experience and to develop a framework for providing the best care for surgical patients, the Society of Hospital Medicine organized the Perioperative Care Work Group in 2015. This framework was designed for interdisciplinary collaboration in building and strengthening perioperative care programs.

METHODS

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognized hospital medicine programs’ need for guidance in developing collaborative care in perioperative medicine and appointed the Perioperative Care Work Group in May 2015. Work group members are perioperative medicine experts from US medical centers. They have extensive knowledge of the literature as well as administrative and clinical experience in a variety of perioperative care models.

Topic Development. Initial work was focused on reviewing and discussing multiple models of perioperative care and exploring the roles that hospital medicine physicians have within these models. Useful information was summarized to guide hospitals and physicians in designing, implementing, and expanding patient-centric perioperative medicine services with a focus on preoperative and postoperative care. A final document was created; it outlines system-level issues in perioperative care, organized by perioperative phases.

Initial Framework. Group members submitted written descriptions of key issues in each of 4 phases: (1) preoperative, (2) day of surgery, (3) postoperative inpatient, and (4) postdischarge. These descriptions were merged and reviewed by the content experts. Editing and discussion from the entire group were incorporated into the final matrix, which highlighted (1) perioperative phase definitions, (2) requirements for patients to move to next phase, (3) elements of care coordination typically provided by surgery, anesthesiology, and medicine disciplines, (4) concerns and risks particular to each phase, (5) unique considerations for each phase, (6) suggested metrics of success, and (7) key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care in an institution. All members provided final evaluation and editing.

Final Approval. The Perioperative Care Matrix for Inpatient Surgeries (PCMIS) was presented to the board of the Society of Hospital Medicine in fall 2015 and was approved for use in centering and directing discussions regarding perioperative care.

Models of Care. The Perioperative Care Work Group surveyed examples of hospitalist engagement in perioperative care and synthesized these into synopses of existing models of care for the preoperative, day-of-surgery, postoperative-inpatient, and postdischarge phases.

RESULTS

Defining Key Concepts and Issues

Hospitalists have participated in a variety of perioperative roles for more than a decade. Roles include performing in-depth preoperative assessments, providing oversight to presurgical advanced practice provider assessments, providing inpatient comanagement and consultation both before and after surgery, and providing postdischarge follow-up within the surgical period for medical comorbidities.

Although a comprehensive look at the entire perioperative period is important, 4 specific phases were defined to guide this work (Figure). The phases identified were based on time relative to surgery, with unique considerations as to the overall perioperative period. Concerns and potential risks specific to each phase were considered (Table 1).

The PCMIS was constructed to provide a single coherent vision of key concepts in perioperative care (Table 2). Also identified were several key questions for determining the effectiveness of perioperative care within an institution (Table 3).

Models of Care

Multiple examples of hospitalist involvement were collected to inform the program development guidelines. The specifics noted among the reviewed practice models are described here.

Preoperative. In some centers, all patients scheduled for surgery are required to undergo evaluation at the institution’s preoperative clinic. At most others, referral to the preoperative clinic is at the discretion of the surgical specialists, who have been informed of the clinic’s available resources. Factors determining whether a patient has an in-person clinic visit, undergoes a telephone-based medical evaluation, or has a referral deferred to the primary care physician (PCP) include patient complexity and surgery-specific risk. Patients who have major medical comorbidities (eg, chronic lung or heart disease) or are undergoing higher risk procedures (eg, those lasting >1 hour, laparotomy) most often undergo a formal clinic evaluation. Often, even for a patient whose preoperative evaluation is completed by a PCP, the preoperative nursing staff will call before surgery to provide instructions and to confirm that preoperative planning is complete. Confirmation includes ensuring that the surgery consent and preoperative history and physical examination documents are in the medical record, and that all recommended tests have been performed. If deficiencies are found, surgical and preoperative clinic staff are notified.

During a typical preoperative clinic visit, nursing staff complete necessary regulatory documentation requirements and ensure that all items on the preoperative checklist are completed before day of surgery. Nurses or pharmacists perform complete medication reconciliation. For medical evaluation at institutions with a multidisciplinary preoperative clinic, patients are triaged according to comorbidity and procedure. These clinics often have anesthesiology and hospital medicine clinicians collaborating with interdisciplinary colleagues and with patients’ longitudinal care providers (eg, PCP, cardiologist). Hospitalists evaluate patients with comorbid medical diseases and address uncontrolled conditions and newly identified symptomatology. Additional testing is determined by evidence- and guideline-based standards. Patients receive preoperative education, including simple template-based medication management instructions. Perioperative clinicians follow up on test results, adjust therapy, and counsel patients to optimize health in preparation for surgery.

Patients who present to the hospital and require urgent surgical intervention are most often admitted to the surgical service, and hospital medicine provides timely consultation for preoperative recommendations. At some institutions, protocols may dictate that certain surgical patients (eg, elderly with hip fracture) are admitted to the hospital medicine service. In these scenarios, the hospitalist serves as the primary inpatient care provider and ensures preoperative medical optimization and coordination with the surgical service to expedite plans for surgery.

Day of Surgery. On the day of surgery, the surgical team verifies all patient demographic and clinical information, confirms that all necessary documentation is complete (eg, consents, history, physical examination), and marks the surgical site. The anesthesia team performs a focused review and examination while explaining the perioperative care plan to the patient. Most often, the preoperative history and physical examination, completed by a preoperative clinic provider or the patient’s PCP, is used by the anesthesiologist as the basis for clinical assessment. However, when information is incomplete or contradictory, surgery may be delayed for further record review and consultation.

Hospital medicine teams may be called to the pre-anesthesia holding area to evaluate acute medical problems (eg, hypertension, hyperglycemia, new-onset arrhythmia) or to give a second opinion in cases in which the anesthesiologist disagrees with the recommendations made by the provider who completed the preoperative evaluation. In either scenario, hospitalists must provide rapid service in close collaboration with anesthesiologists and surgeons. If a patient is found to be sufficiently optimized for surgery, the hospitalist clearly documents the evaluation and recommendation in the medical record. For a patient who requires further medical intervention before surgery, the hospitalist often coordinates the immediate disposition (eg, hospital admission or discharge home) and plans for optimization in the timeliest manner possible.

Occasionally, hospitalists are called to evaluate a patient in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for a new or chronic medical problem before the patient is transitioned to the next level of care. At most institutions, all PACU care is provided under the direction of anesthesiology, so it is imperative to collaborate with the patient’s anesthesiologist for all recommendations. When a patient is to be discharged home, the hospitalist coordinates outpatient follow-up plans for any medical issues to be addressed postoperatively. Hospitalists also apply their knowledge of the limitations of non–intensive care unit hospital care to decisions regarding appropriate triage of patients being admitted after surgery.

Postoperative Inpatient. Hospitalists provide a 24/7 model of care that deploys a staff physician for prompt assessment and management of medical problems in surgical patients. This care can be provided as part of the duties of a standard hospital medicine team or can be delivered by a dedicated perioperative medical consultation and comanagement service. In either situation, the type of medical care, comanagement or consultation, is determined at the outset. As consultants, hospitalists provide recommendations for medical care but do not write orders or take primary responsibility for management. Comanagement agreements are common, especially for orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery; these agreements delineate the specific circumstances and responsibilities of the hospitalist and surgical teams. Indications for comanagement, which may be identified during preoperative clinic evaluation or on admission, include uncontrolled or multiple medical comorbidities or the development of nonsurgical complications in the perioperative period. In the comanagement model, care of most medical issues is provided at the discretion of the hospitalist. Although this care includes order-writing privileges, management of analgesics, wounds, blood products, and antithrombotics is usually reserved for the surgical team, with the hospitalist only providing recommendations. In some circumstances, hospitalists may determine that the patient’s care requires consultation with other specialists. Although it is useful for the hospitalist to speak directly with other consultants and coordinate their recommendations, the surgical service should agree to the involvement of other services.

In addition to providing medical care throughout a patient’s hospitalization, the hospitalist consultant is crucial in the discharge process. During the admission, ideally in collaboration with a pharmacist, the hospitalist reviews the home medications and may change chronic medications. The hospitalist may also identify specific postdischarge needs of which the surgical team is not fully aware. These medical plans are incorporated through shared responsibility for discharge orders or through a reliable mechanism for ensuring the surgical team assumes responsibility. Final medication reconciliation at discharge, and a plan for prior and new medications, can be formulated with pharmacy assistance. Finally, the hospitalist is responsible for coordinating medically related hospital follow-up and handover back to the patient’s longitudinal care providers. The latter occurs through inclusion of medical care plans in the discharge summary completed by the surgical service and, in complex cases, through direct communication with the patient’s outpatient providers.

For some patients, medical problems eclipse surgical care as the primary focus of management. Collaborative discussion between the medical and surgical teams helps determine if it is more appropriate for the medical team to become the primary service, with the surgical team consulting. Such triage decisions should be jointly made by the attending physicians of the services rather than by intermediaries.

Postdischarge. Similar to their being used for medical problems after hospitalization, hospitalist-led postdischarge and extensivist clinics may be used for rapid follow-up of medical concerns in patients discharged after surgical admissions. A key benefit of this model is increased availability over what primary care clinics may be able to provide on short notice, particularly for patients who previously did not have a PCP. Additionally, the handover of specific follow-up items is more streamlined because the transition of care is between hospitalists from the same institution. Through the postdischarge clinic, hospitalists can provide care through either clinic visits or telephone-based follow-up. Once a patient’s immediate postoperative medical issues are fully stabilized, the patient can be transitioned to long-term primary care follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The United States is focused on sensible, high-value care. Perioperative care is burgeoning with opportunities for improvement, including reducing avoidable complications, developing systems for early recognition and treatment of complications, and streamlining processes to shorten length of stay and improve patient experience. The PCMIS provides the needed platform to catalyze detailed collaborative work between disciplines engaged in perioperative care.

As average age and level of medical comorbidity increase among surgical patients, hospitalists will increasingly be called on to assist in perioperative care. Hospitalists have long been involved in caring for medically complex surgical patients, through comanagement, consultation, and preoperative evaluations. As a provider group, hospitalists have comprehensive skills in quality and systems improvement, and in program development across hospital systems nationwide. Hospitalists have demonstrated their value by focusing on improving patient outcomes and enhancing patient engagement and experiences. Additionally, the perioperative period is fraught with multiple and complicated handoffs, a problem area for which hospital medicine has pioneered solutions and developed unique expertise. Hospital medicine is well prepared to provide skilled and proven leadership in the timely development, improvement, and expansion of perioperative care for this increasingly older and chronically ill population.

Hospitalists are established in multiple perioperative roles for high-risk surgical patients and have the opportunity to expand optimal patient-centric perioperative care systems working in close concert with surgeons and anesthesiologists. The basics of developing these systems include (1) assessing risk for medical complications, (2) planning for perioperative care, (3) developing programs aimed at risk reduction for preventable complications and early identification and intervention for unavoidable complications, and (4) guiding quality improvement efforts, including planning for frequent handoffs and transitions.

As a key partner in developing comprehensive programs in perioperative care, hospital medicine will continue to shape the future of hospital care for all patients. The PCMIS, as developed with support from the Society of Hospital Medicine, will aid efforts to achieve the best perioperative care models for our surgical patients.

Disclosures

Financial activities outside the submitted work: Drs. Pfeifer and Jaffer report payment for development of educational presentations; Dr. Grant reports payment for expert testimony pertaining to hospital medicine; Drs. Grant and Jaffer report royalties from publishing; Drs. Thompson, Pfiefer, Grant, Slawski, and Jaffer report travel expenses for speaking and serving on national committees; and Drs. Slawski and Jaffer serve on the board of the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement. The other authors have nothing to report.

1. Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 (Current Population Reports, P25-1143). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Steiner C, Andrews R, Barrett M, Weiss A. HCUP Projections: Cost of Inpatient Discharges 2003 to 2013 (Rep 2013-01). Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/projections/2013-01.pdf. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed May 26, 2016.

3. Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Cheng HQ, et al. Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2004-2010. PubMed

4. Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219-225. PubMed

5. Carr AM, Irigoyen M, Wimmer RS, Arbeter AM. A pediatric residency experience with surgical co-management. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):144-148. PubMed

6. Della Rocca GJ, Moylan KC, Crist BD, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Mehr DR. Comanagement of geriatric patients with hip fractures: a retrospective, controlled, cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2013;4(1):10-15. PubMed

7. Fisher AA, Davis MW, Rubenach SE, Sivakumaran S, Smith PN, Budge MM. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(3):172-178. PubMed

8. Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Kates SL, McCann RM. Geriatric co-management of proximal femur fractures: total quality management and protocol-driven care result in better outcomes for a frail patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1349-1356. PubMed

9. Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al; Hospitalist-Orthopedic Team Trial Investigators. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38. PubMed

10. Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. Principles of comanagement and the geriatric fracture center. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):183-189. PubMed

11. Merli GJ. The hospitalist joins the surgical team. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):67-69. PubMed

12. Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):796-801. PubMed

13. Pinzur MS, Gurza E, Kristopaitis T, et al. Hospitalist-orthopedic co-management of high-risk patients undergoing lower extremity reconstruction surgery. Orthopedics. 2009;32(7):495. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Rappaport DI, Cerra S, Hossain J, Sharif I, Pressel DM. Pediatric hospitalist preoperative evaluation of children with neuromuscular scoliosis. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(12):684-688. PubMed

16. Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31. PubMed

17. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368. PubMed

18. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

19. Whinney C, Michota F. Surgical comanagement: a natural evolution of hospitalist practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):394-397. PubMed

1. Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 (Current Population Reports, P25-1143). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Steiner C, Andrews R, Barrett M, Weiss A. HCUP Projections: Cost of Inpatient Discharges 2003 to 2013 (Rep 2013-01). Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/projections/2013-01.pdf. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed May 26, 2016.

3. Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Cheng HQ, et al. Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2004-2010. PubMed

4. Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist care model on mortality of elderly patients with hip fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219-225. PubMed

5. Carr AM, Irigoyen M, Wimmer RS, Arbeter AM. A pediatric residency experience with surgical co-management. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):144-148. PubMed

6. Della Rocca GJ, Moylan KC, Crist BD, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Mehr DR. Comanagement of geriatric patients with hip fractures: a retrospective, controlled, cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2013;4(1):10-15. PubMed

7. Fisher AA, Davis MW, Rubenach SE, Sivakumaran S, Smith PN, Budge MM. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(3):172-178. PubMed

8. Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Kates SL, McCann RM. Geriatric co-management of proximal femur fractures: total quality management and protocol-driven care result in better outcomes for a frail patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1349-1356. PubMed

9. Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al; Hospitalist-Orthopedic Team Trial Investigators. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38. PubMed

10. Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. Principles of comanagement and the geriatric fracture center. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):183-189. PubMed

11. Merli GJ. The hospitalist joins the surgical team. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):67-69. PubMed

12. Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):796-801. PubMed

13. Pinzur MS, Gurza E, Kristopaitis T, et al. Hospitalist-orthopedic co-management of high-risk patients undergoing lower extremity reconstruction surgery. Orthopedics. 2009;32(7):495. PubMed

14. Rappaport DI, Adelizzi-Delany J, Rogers KJ, et al. Outcomes and costs associated with hospitalist comanagement of medically complex children undergoing spinal fusion surgery. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):233-241. PubMed

15. Rappaport DI, Cerra S, Hossain J, Sharif I, Pressel DM. Pediatric hospitalist preoperative evaluation of children with neuromuscular scoliosis. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(12):684-688. PubMed

16. Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31. PubMed

17. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):363-368. PubMed

18. Simon TD, Eilert R, Dickinson LM, Kempe A, Benefield E, Berman S. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23-30. PubMed

19. Whinney C, Michota F. Surgical comanagement: a natural evolution of hospitalist practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):394-397. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Principles and Characteristics of an HMG

With the continuing growth of the specialty of hospital medicine, the capabilities and performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) varies significantly. There are few guidelines that HMGs can reference as tools to guide self‐improvement. To address this deficiency, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Board of Directors authorized a process to identify the key principles and characteristics of an effective HMG.

METHODS

Topic Development and Validation Prework

In providing direction to this effort, the SHM board felt that the principles and characteristics should be directed at both hospitals and hospitalists, addressing the full range of managerial, organizational, clinical, and quality activities necessary to achieve effectiveness. Furthermore, the board defined effectiveness as consisting of 2 components. First, the HMG must assure that the patients managed by hospitalists receive high‐quality care that is sensitive to their needs and preferences. Second, the HMG must understand that the central role of the hospitalist is to coordinate patient care and foster interdisciplinary communication across the care continuum to provide optimal patient outcomes.

The SHM board appointed an HMG Characteristics Workgroup consisting of individuals who have experience with a wide array of HMG models and who could offer expert opinions on the subject. The HMG Characteristics Workgroup felt it important to review the work of other organizations that develop and administer criteria, standards, and/or requirements for healthcare organizations. Examples cited were the American College of Surgeons[1]; The Joint Commission[2]; American Nurse Credentialing Center[3]; the National Committee for Quality Assurance[4]; the American Medical Group Association[5]; and the American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses.[6]

In March 2012 and April 2012, SHM staff reviewed the websites and published materials of these organizations. For each program, information was captured on the qualifications of applicants, history of the program, timing of administering the program, the nature of recognition granted, and the program's keys to success. The summary of these findings was shared with the workgroup.

Background research and the broad scope of characteristics to be addressed led to the workgroup's decision to develop the principles and characteristics using a consensus process, emphasizing expert opinion supplemented by feedback from a broad group of stakeholders.

Initial Draft

During April 2012 and May 2012, the HMG Characteristics Workgroup identified 3 domains for the key characteristics: (1) program structure and operations, (2) clinical care delivery, and (3) organizational performance improvement. Over the course of several meetings, the HMG Characteristics Workgroup developed an initial draft of 83 characteristics, grouped into 29 subgroups within the 3 domains.

From June 2012 to November 2012, this initial draft was reviewed by a broad cross section of the hospital medicine community including members of SHM's committees, a group of academic hospitalists, focus groups in 2 communities (Philadelphia and Boston), and the leaders of several regional and national hospitalist management companies. Quantitative and qualitative feedback was obtained.

In November 2012, the SHM Board of Directors held its annual leadership meeting, attended by approximately 25 national hospitalist thought leaders and chairpersons of SHM committees. At this meeting, a series of exercises were conducted in which these leaders of the hospital medicine movement, including the SHM board members, were each assigned individual characteristics and asked to review and edit them for clarity and appropriateness.

As a result of feedback at that meeting and subsequent discussion by the SHM board, the workgroup was asked to modify the characteristics in 3 ways. First, the list should be streamlined, reducing the number of characteristics. Second, the 3 domains should be eliminated, and a better organizing framework should be created. Third, additional context should be added to the list of characteristics.

Second Draft

During the period from November 2012 to December 2012, the HMG Characteristics Workgroup went through a 2‐step Delphi process to consolidate characteristics and/or eliminate characteristics that were redundant or unnecessary. In the first step, members of the workgroup rated each characteristic from 1 to 3. A rating of 1 meant not important; good quality, but not required for an effective HMG. A rating of 2 meant important; most effective HMGs will meet requirement. A rating of 3 meant highly important; mandatory for an effective HMG. In the second step, members of the workgroup received feedback on the scores for each characteristic and came to a consensus on which characteristics should be eliminated or merged with other characteristics.

As a result, the number of characteristics was reduced and consolidated from 83 to 47, and a new framing structure was defined, replacing the 3 domains with 10 organizing principles. Finally, a rationale for each characteristic was added, defending its inclusion in the list. In addition, consideration was given to including a section describing how an HMG could demonstrate that their organization met each characteristic. However, the workgroup and the board decided that these demonstration requirements should be vetted before they were published.

From January 2013 to June 2013, the revised key principles and characteristics were reviewed by selected chairpersons of SHM committees and by 2 focus groups of HMG leaders. These reviews were conducted at the SHM Annual Meeting. Finally, in June 2013, the Committee on Clinical Leadership of the American Hospital Association reviewed and commented on the draft of the principles and characteristics.

In addition, based on feedback received from the reviewers, the wording of many of the characteristics went through revisions to assure precision and clarity. Before submission to the Journal of Hospital Medicine, a professional editor was engaged to assure that the format and language of the characteristics were clear and consistent.

Final Approval

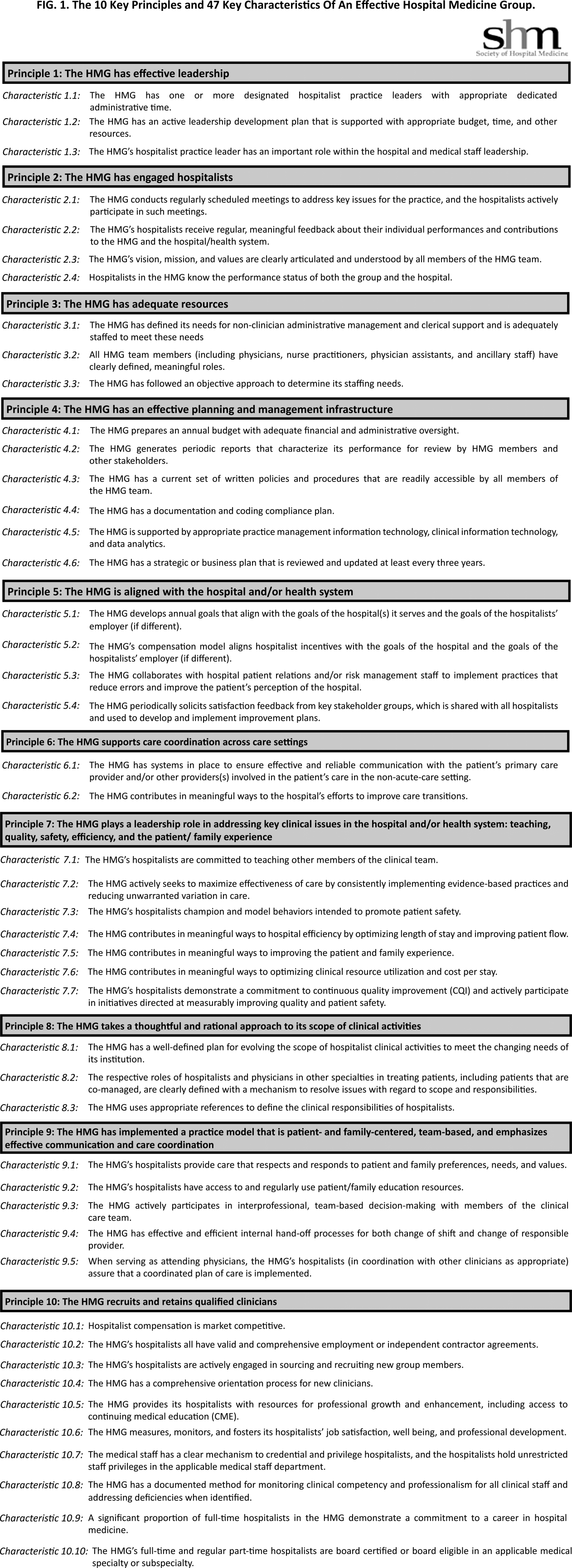

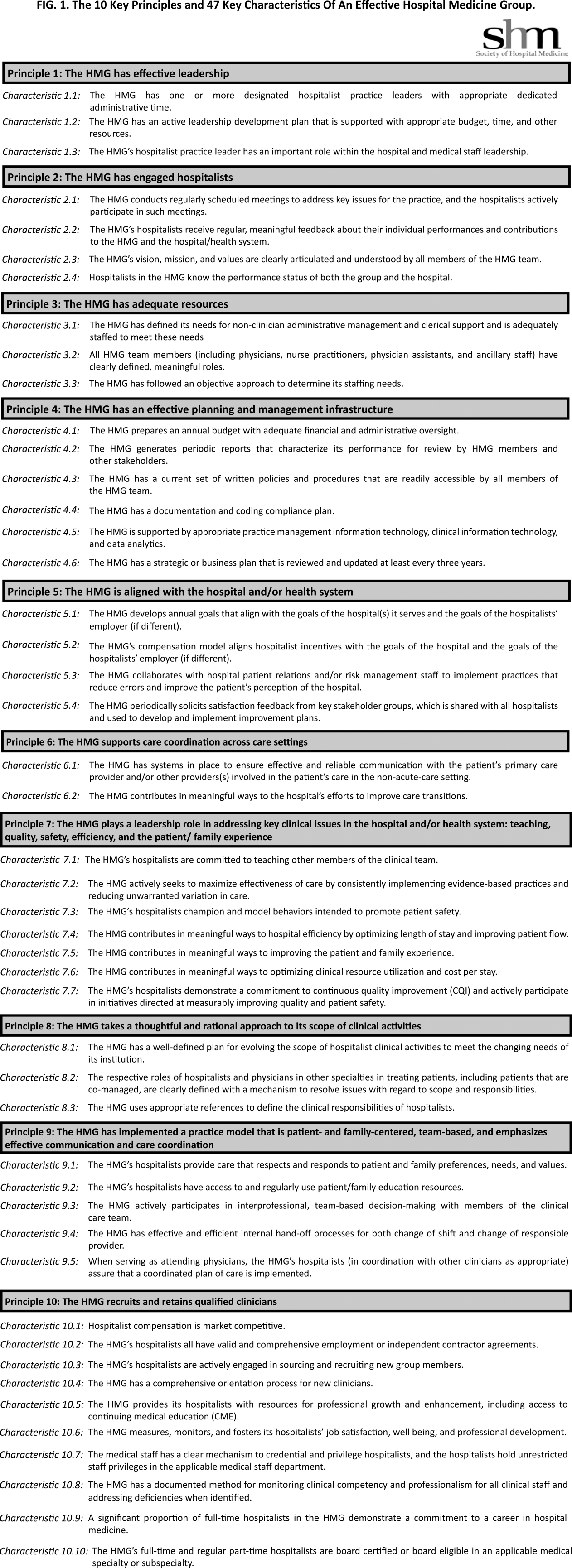

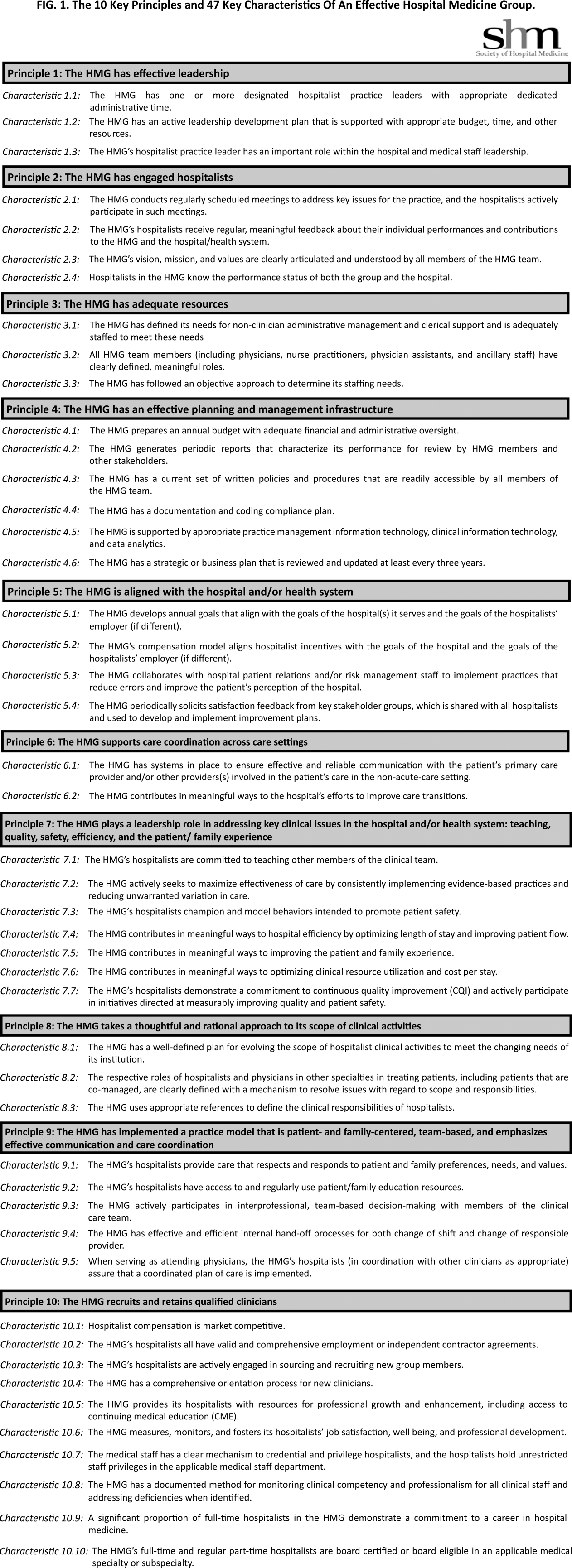

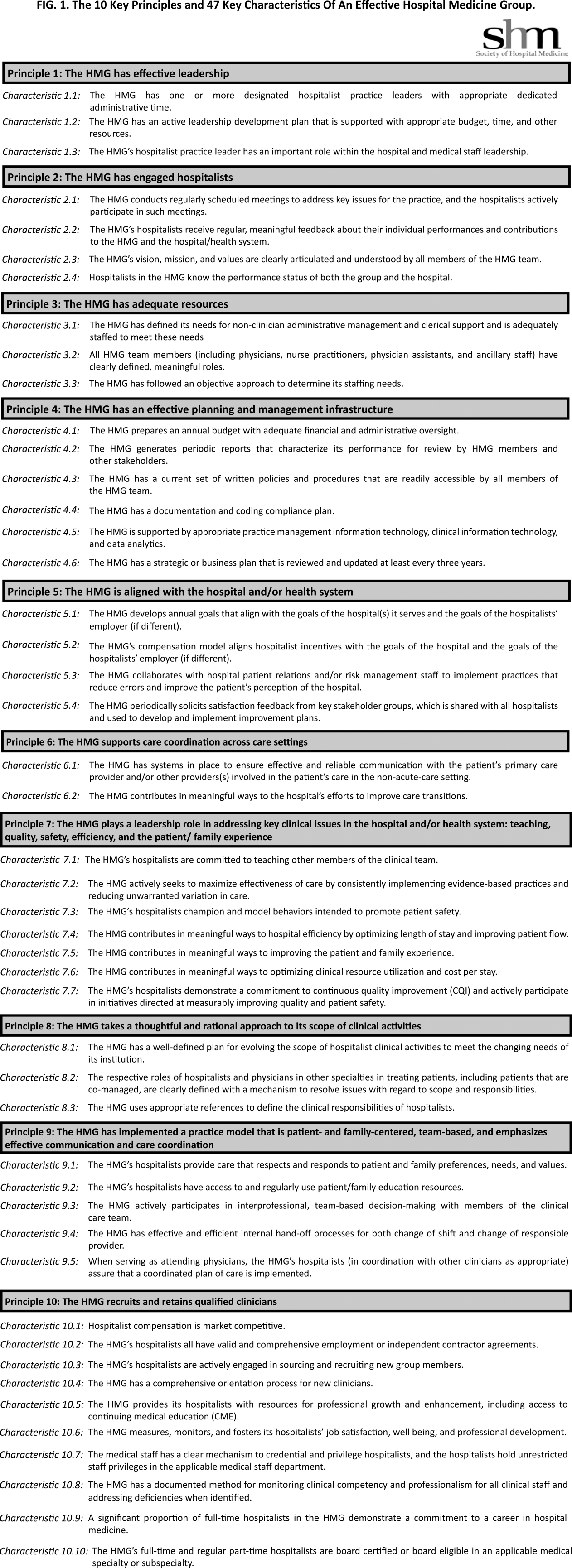

The final draft of the 10 principles and 47 characteristics was approved for publication at a meeting of the SHM Board of Directors in September 2013 (Figure 1).

RESULTS

A recurring issue that the workgroup addressed was the applicability of the characteristics from 1 practice setting to another. Confounding factors include the HMG's employment/organizational model (eg, hospital employed, academic, multispecialty group, private practice, and management company), its population served (eg, adult vs pediatric, more than 1 hospital), and the type of hospital served (eg, academic vs community, the hospital has more than 1 HMG). The workgroup has made an effort to assure that all 47 characteristics can be applied to every type of HMG.

In developing the 10 principles, the workgroup attempted to construct a list of the basic ingredients needed to build and sustain an effective HMG. These 10 principles stand on their own, independent of the 47 key characteristics, and include issues such as effective leadership, clinician engagement, adequate resources, management infrastructure, key hospitalist roles and responsibilities, alignment with the hospital, and the recruitment and retention of qualified hospitalists.

A more detailed version of the Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG is available in the online version of this article (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). The online Appendix includes the rationales for each of the characteristics, guidance on how to provide feedback to the SHM on the framework, and the SHM's plan for further development of the key principles and characteristics.

DISCUSSION

To address the variability in capabilities and performance of HMGs, these principles and characteristics are designed to provide a framework for HMGs seeking to conduct self‐assessments and develop pathways for improvement.

Although there may be HMG arrangements that do not directly involve the hospital and its executive team, and therefore alternative approaches may make sense, for most HMGs hospitals are directly involved with the HMG as either an employer or a contractor. For that reason, the Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG is written for 2 audiences: the executive leadership of the hospital (most specifically the chief medical officer or a similar role) and the hospitalists in the HMG (most specifically the practice medical director). To address the key characteristics requires the active participation of both parties. For the hospital executives, the framework establishes expectations for the HMG. For the hospitalists, the framework provides guidance in the development of an improvement plan.

Hospital executives and hospitalists can use the key characteristics in a broad spectrum of ways. The easiest and least formalized approach would be to use the framework as the basis of an ongoing dialogue between the hospital leadership and the HMG. A more formal approach would be to use the framework to guide the planning and budgeting activities of the HMG. Finally, a hospital or health system can use the key principles and characteristics as a way to evaluate their affiliated HMG(s)for example, the HMG must address 80% of the 47 characteristics.

The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG should be considered akin to the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine previously published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.[7] However, instead of focusing on the competencies of individual physicians, this framework focuses on the characteristics of hospitalist groups. Just as a physician or other healthcare provider is not expected to demonstrate competency for every element in the core competencies document, an HMG does not need to have all 47 characteristics to be effective. Effective hospitalists may have skills other than those listed in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. Similarly, the 47 characteristics do not represent an exhaustive list of every desirable HMG attribute. In general, effective HMGs should possess most of the characteristics.

In applying the framework, the HMG should not simply attempt to evaluate each characteristic with a yes or no assessment. For HMGs responding yes, there may be a wide range of performancefrom meeting the bare minimum requirements to employing sophisticated, expansive measures to excel in the characteristic.

SHM encourages hospital leaders and HMG leaders to use these characteristics to perform an HMG self‐assessment and to develop a plan. The plan could address implementation of selected characteristics that are not currently being addressed by the HMG or the development of additional behaviors, tools, resources, and capabilities that more fully incorporate those characteristics for which the HMG meets only minimum requirements. In addition, the plan could address the impact that a larger organization (eg, health system, hospital, or employer) may have on a given characteristic.

As outlined above, the process used to develop the Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG was grounded in expert opinion and extensive review and feedback. HMGs that use the framework should recognize that others might have a different opinion. For example, characteristic 5.2 states, The HMG's compensation model aligns hospitalist incentives with the goals of the hospital and the goals of the hospitalist's employer (if different). There are likely to be experienced hospitalist leaders who believe that an effective HMG does not need to have an incentive compensation system. However, the consensus process employed to develop the key characteristics led to the conclusion that an effective HMG should have an incentive compensation system.

The publication of the Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG may lead to negative and/or unintended consequences. A self‐assessment by an HMG using this framework could require a significant level of effort on behalf of the HMG, whereas implementing remedial efforts to address the characteristics could require an investment of time and money that could take away from other important issues facing the HMG. Many HMGs may be held accountable for addressing these characteristics without the necessary financial support from their hospital or medical group. Finally, the publication of the document could create a backlash from members of the hospitalist community who do not think that the SHM should be in the business of defining what characterizes an effective HMG, rather that this definition should be left to the marketplace.

Despite these concerns, the leadership of the SHM expects that the publication of the Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG will lead to overall improvement in the capabilities and performance of HMGs.

CONCLUSIONS

The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective HMG have been designed to be aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine. These principles and characteristics could provide a framework for HMGs seeking to conduct self‐assessments, outlining a pathway for improvement, and better defining the central role of hospitalists in coordinating team‐based, patient‐centered care in the acute care setting.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Patrick Cawley, MD: none; Steven Deitelzweig, MD: none; Leslie Flores, MHA: provides consulting to hospital medicine groups; Joseph A. Miller, MS: none; John Nelson, MD: provides consulting to hospital medicine groups; Scott Rissmiller, MD: none; Laurence Wellikson, MD: none; Winthrop F. Whitcomb, MD: provides consulting to hospital medicine groups.

- American College of Surgeons. New verification site visit outcomes. Available at: http://www.facs.org/trauma/verifivisitoutcomes.html. Accessed September 3, 2013.

- Hospital accreditation standards 2012. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2012. Available at: Amazon.com: http://www.amazon.com/Hospital‐Accreditation‐Standards‐Joint‐Commission/dp/1599404257

- The magnet model: components and sources of evidence. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurse Credentialing Center; 2011. Available at: Amazon.com: http://www.amazon.com/Magnet‐Model‐Components‐Sources‐Evidence/dp/1935213229.

- Patient Centered Medical Home Standards and Guidelines. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Available at: https://inetshop01.pub.ncqa.org/Publications/deptCate.asp?dept_id=21(suppl 1):2–95.

With the continuing growth of the specialty of hospital medicine, the capabilities and performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) varies significantly. There are few guidelines that HMGs can reference as tools to guide self‐improvement. To address this deficiency, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Board of Directors authorized a process to identify the key principles and characteristics of an effective HMG.

METHODS

Topic Development and Validation Prework

In providing direction to this effort, the SHM board felt that the principles and characteristics should be directed at both hospitals and hospitalists, addressing the full range of managerial, organizational, clinical, and quality activities necessary to achieve effectiveness. Furthermore, the board defined effectiveness as consisting of 2 components. First, the HMG must assure that the patients managed by hospitalists receive high‐quality care that is sensitive to their needs and preferences. Second, the HMG must understand that the central role of the hospitalist is to coordinate patient care and foster interdisciplinary communication across the care continuum to provide optimal patient outcomes.

The SHM board appointed an HMG Characteristics Workgroup consisting of individuals who have experience with a wide array of HMG models and who could offer expert opinions on the subject. The HMG Characteristics Workgroup felt it important to review the work of other organizations that develop and administer criteria, standards, and/or requirements for healthcare organizations. Examples cited were the American College of Surgeons[1]; The Joint Commission[2]; American Nurse Credentialing Center[3]; the National Committee for Quality Assurance[4]; the American Medical Group Association[5]; and the American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses.[6]

In March 2012 and April 2012, SHM staff reviewed the websites and published materials of these organizations. For each program, information was captured on the qualifications of applicants, history of the program, timing of administering the program, the nature of recognition granted, and the program's keys to success. The summary of these findings was shared with the workgroup.

Background research and the broad scope of characteristics to be addressed led to the workgroup's decision to develop the principles and characteristics using a consensus process, emphasizing expert opinion supplemented by feedback from a broad group of stakeholders.

Initial Draft