User login

Accuracy of Hospitalist‐Performed HCUE

Hand‐carried ultrasound echocardiography (HCUE) can help noncardiologists answer well‐defined questions at patients' bedsides in less than 10 minutes.1, 2 Indeed, intensivists3 and emergency department physicians4 already use HCUE to make rapid, point‐of‐care assessments. Since cardiovascular diagnoses are common among general medicine inpatients, HCUE may become an important skill for hospitalists to learn.5

However, uncertainty exists about the duration of HCUE training for hospitalists. In 2002, experts from the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) published recommendations on training requirements for HCUE.6 With limited data on the safety or performance of HCUE training programs, which had just begun to emerge, the ASE borrowed from the proven training recommendations for standard echocardiography (SE). They recommended that all HCUE trainees, cardiologist and noncardiologist alike, complete level 1 SE training: 75 personally‐performed and 150 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations. Since then, however, several HCUE training programs designed for noncardiologists have emerged.2, 5, 710 These alternative programs suggest that the ASE's recommended duration of training may be too long, particularly for focused HCUE that is limited to a few relatively simple assessments. It is important not to overshoot the requirements of HCUE training, because doing so may discourage groups of noncardiologists, like hospitalists, who may derive great benefits from HCUE.11

To address this uncertainty for hospitalists, we first developed a brief HCUE training program to assess 6 important cardiac abnormalities. We then studied the diagnostic accuracy of HCUE by hospitalists as a test of these 6 cardiac abnormalities assessed by SE.

Patients and Methods

Setting and Subjects

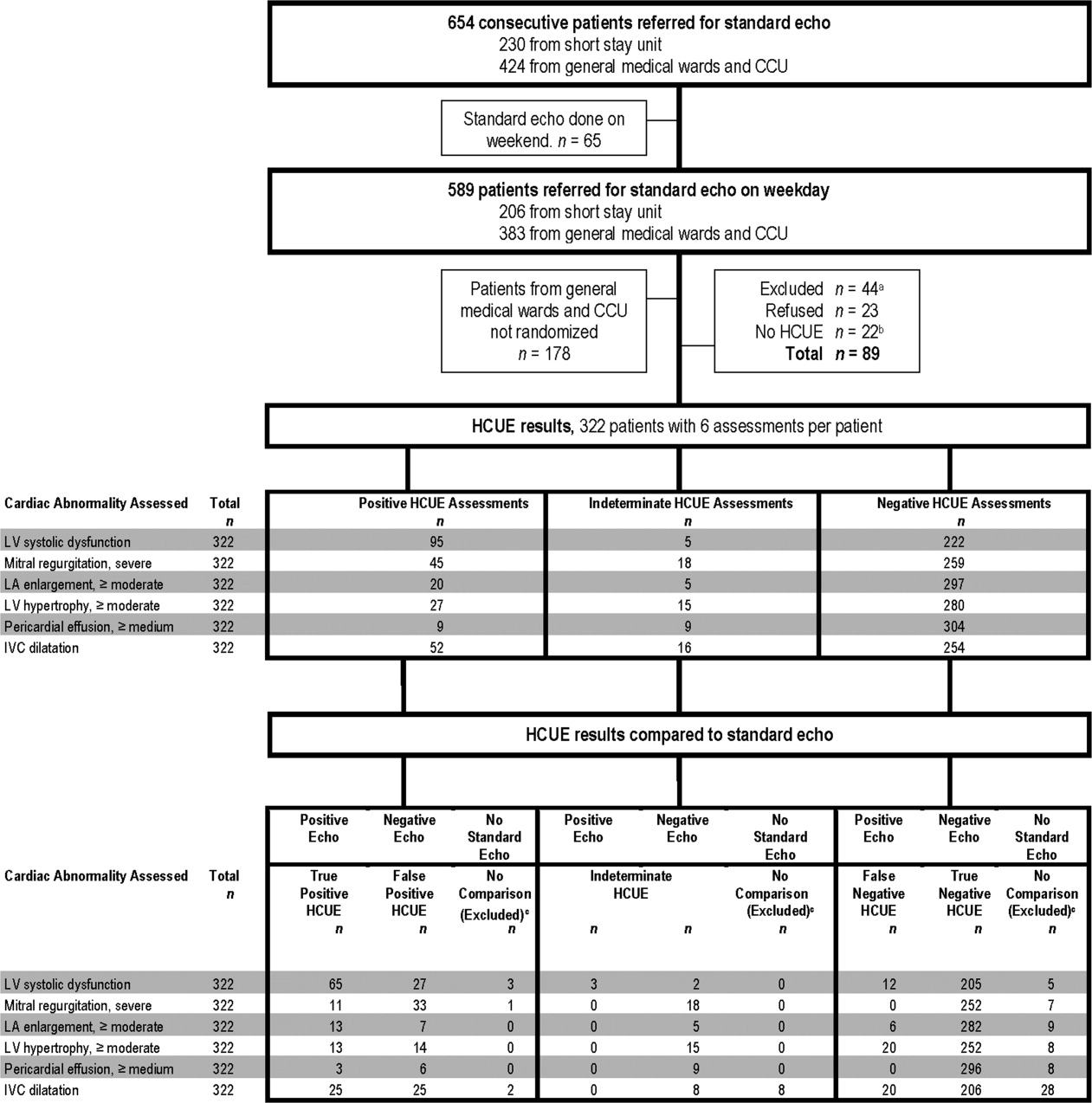

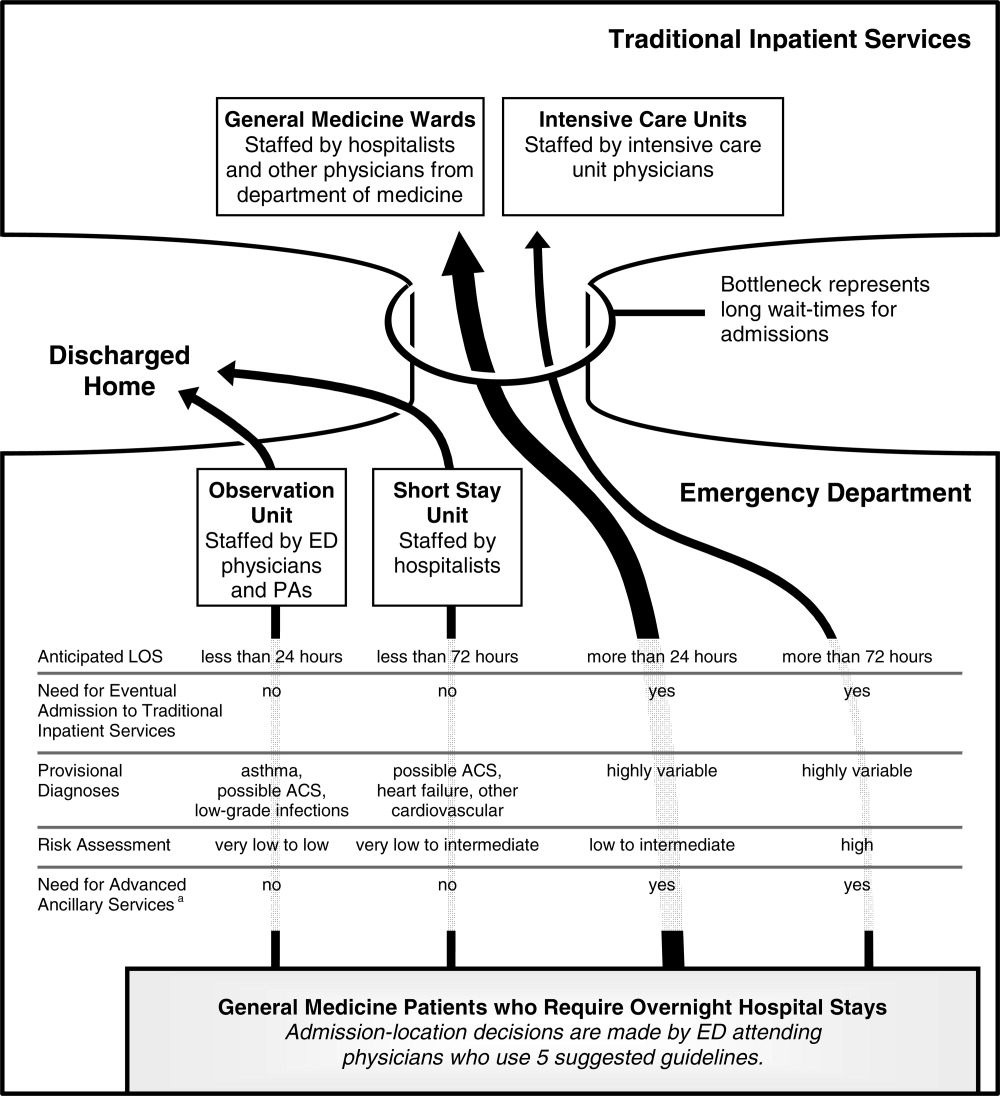

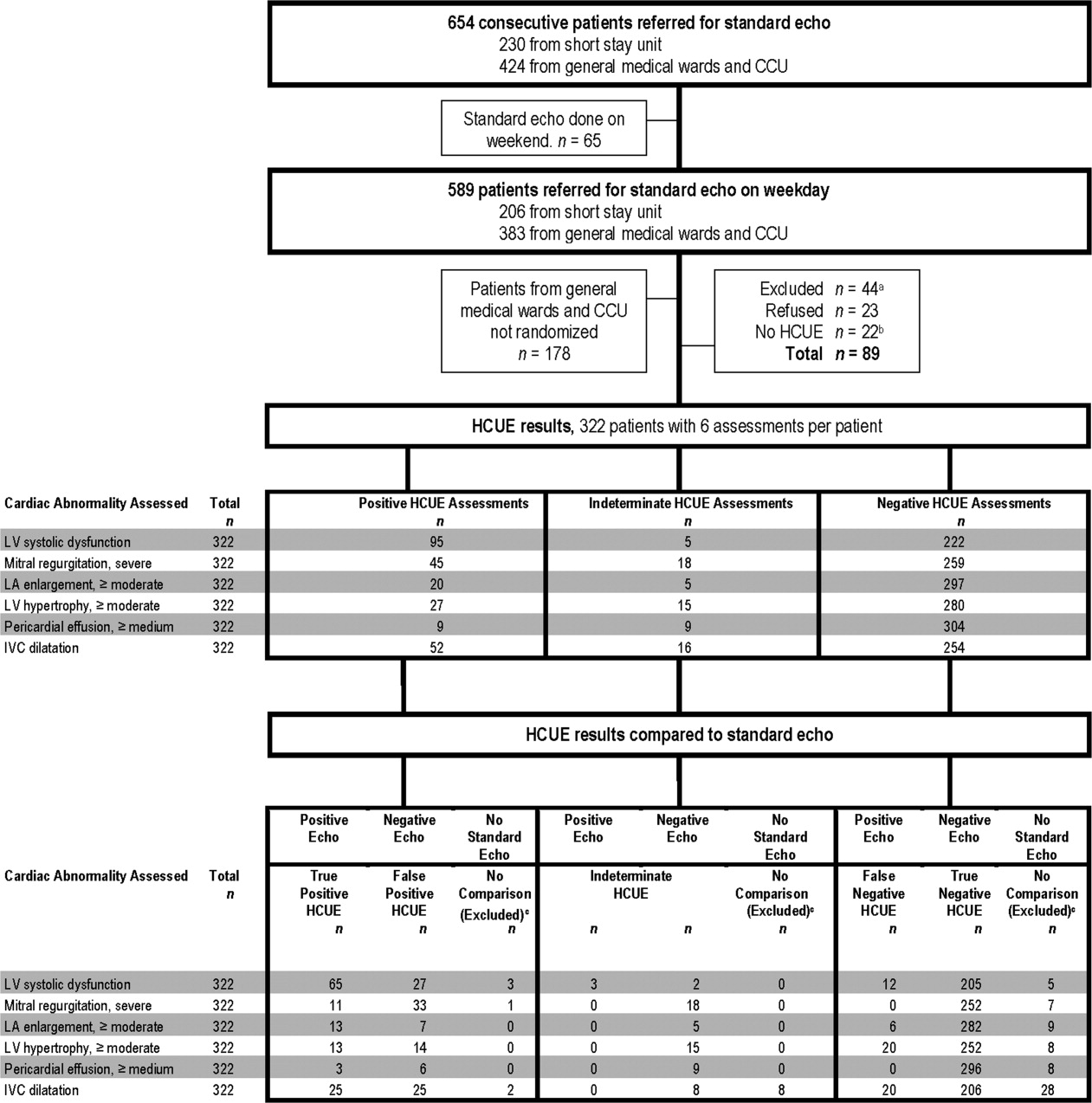

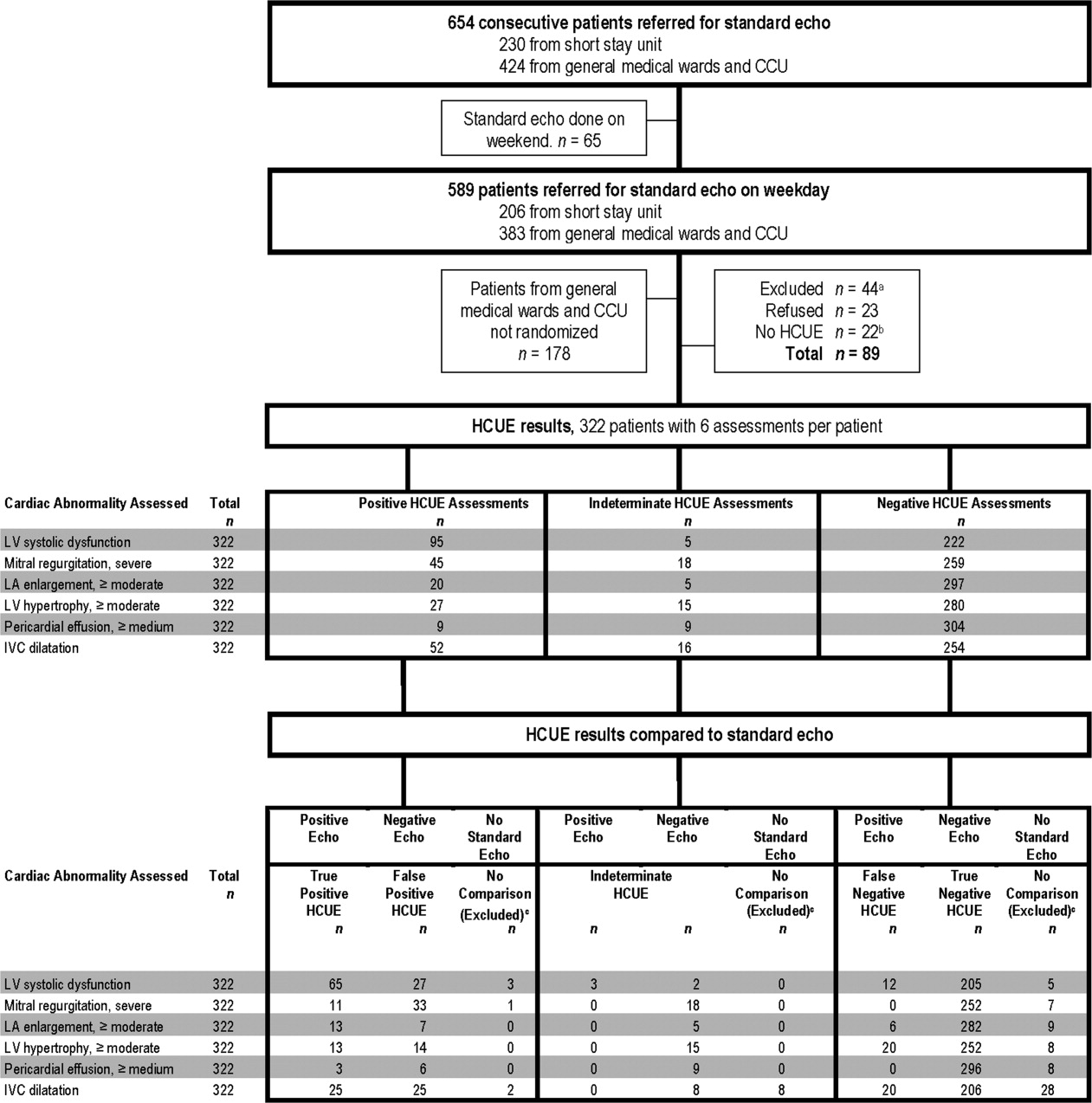

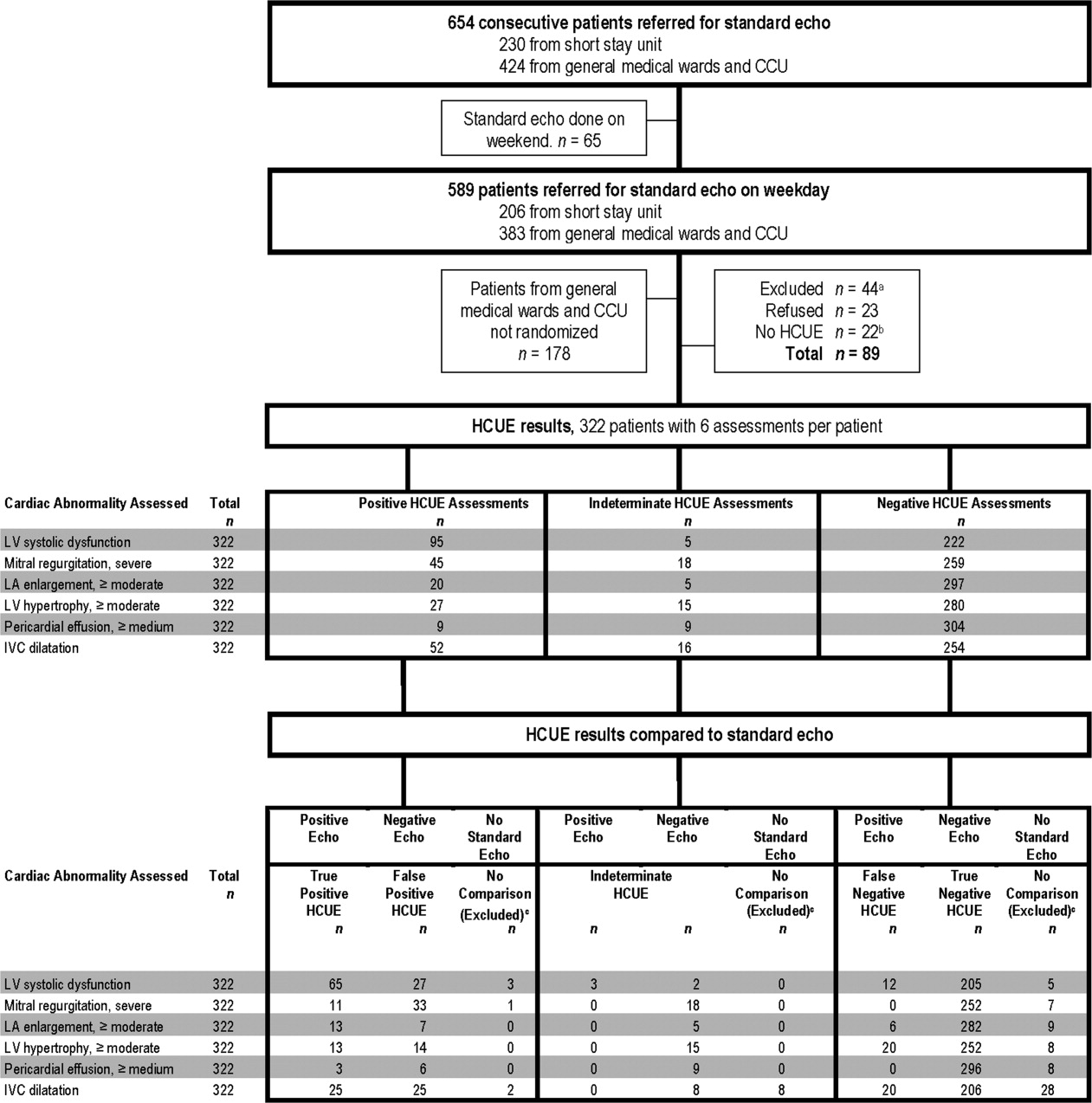

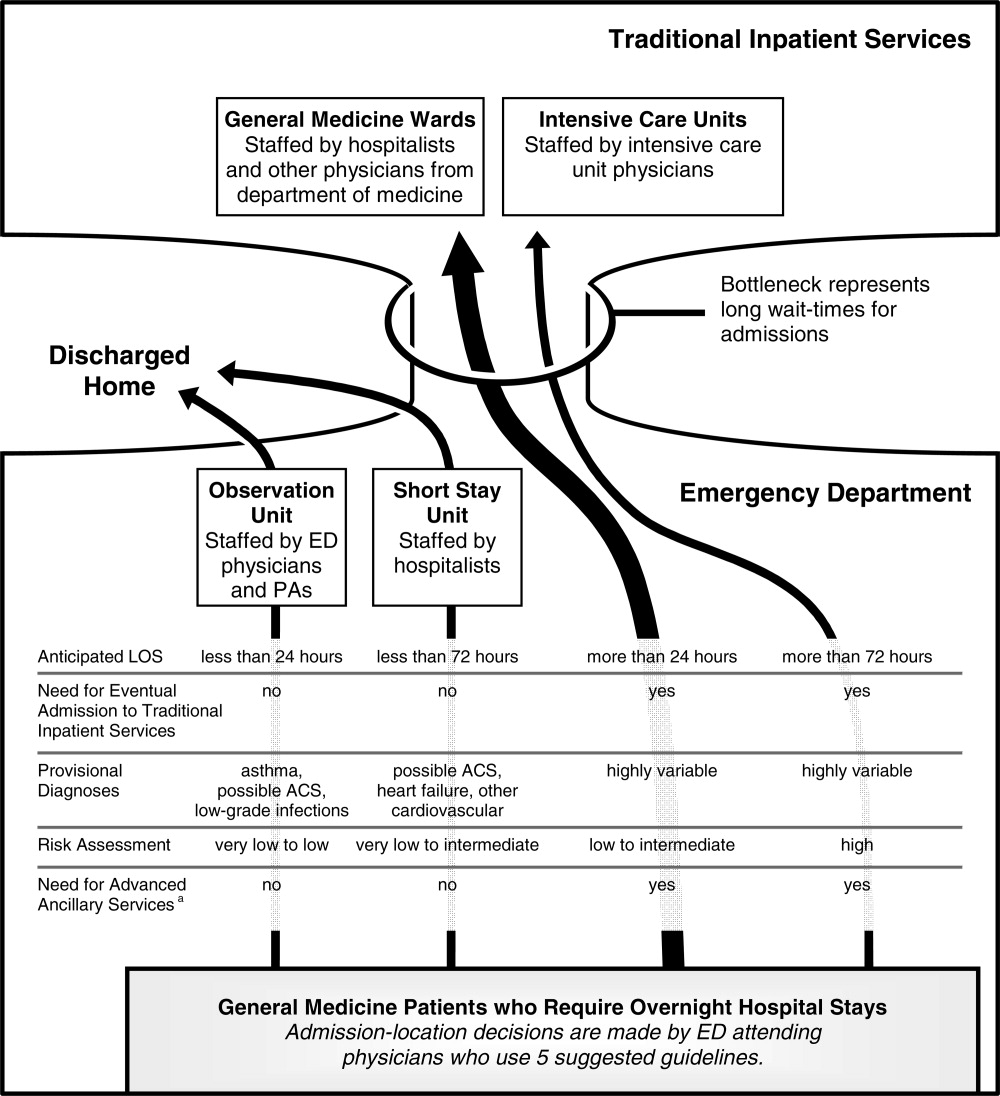

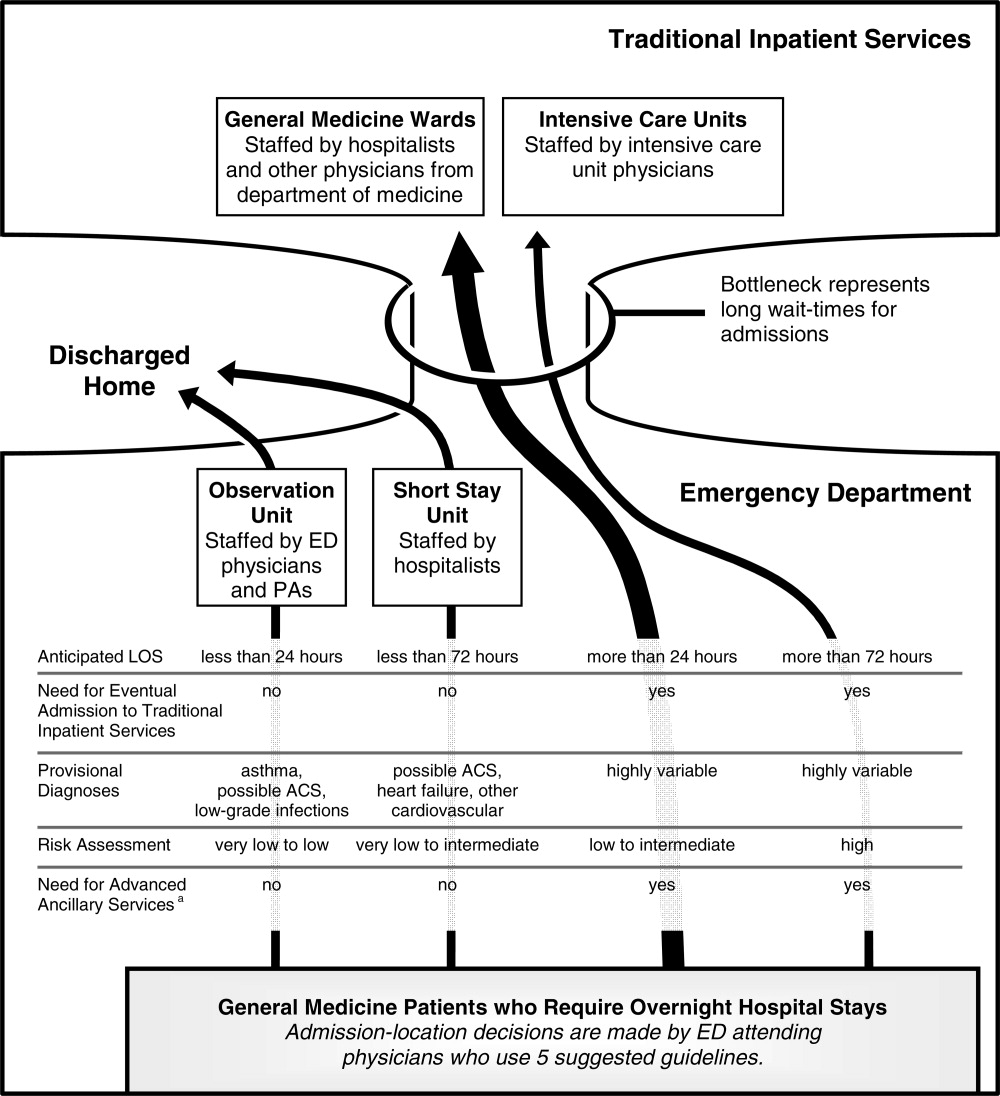

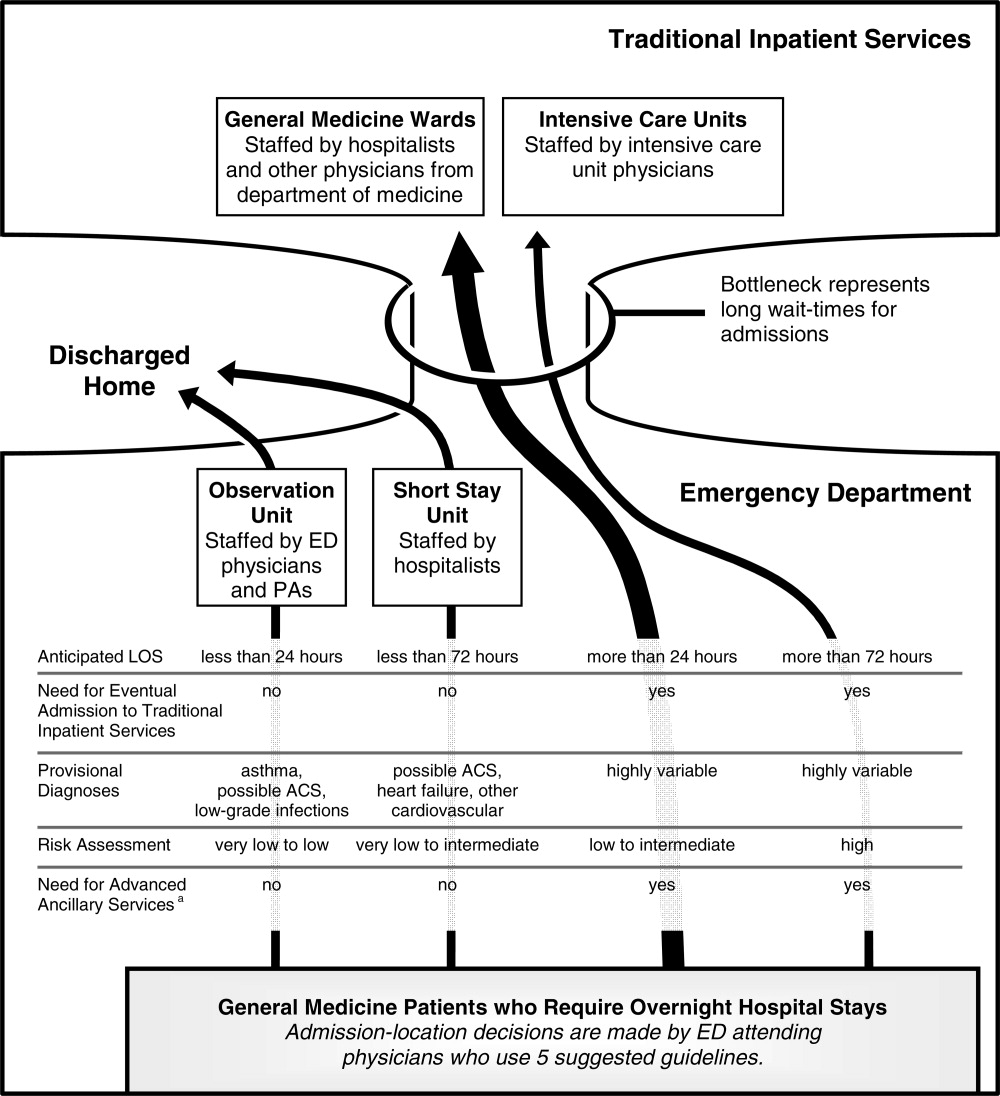

This prospective cohort study was performed at Stroger Hospital of Cook County, a 500‐bed public teaching hospital in Chicago, IL, from March through May of 2007. The cohort was adult inpatients who were referred for SE on weekdays from 3 distinct patient care units (Figure 1). We used 2 sampling modes to balance practical constraints (short‐stay unit [SSU] patients were more localized and, therefore, easier to study) with clinical diversity. We consecutively sampled patients from our SSU, where adults with provisional cardiovascular diagnoses are admitted if they might be eligible for discharge with in 3 days.12 But we used random number tables with a daily unique starting point to randomly sample patients from the general medical wards and the coronary care unit (CCU). Patients were excluded if repositioning them for HCUE was potentially harmful. The study was approved by our hospital's institutional review board, and we obtained written informed consent from all enrolled patients.

SE Protocol

As part of enrolled patients' routine clinical care, SE images were acquired and interpreted in the usual fashion in our hospital's echocardiography laboratory, which performs SE on over 7,000 patients per year. Echocardiographic technicians acquired images with a General Electric Vivid 7 cardiac ultrasound machine (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a GE M4S 1.8 to 3.4 MHz cardiac transducer (General Electric). Technicians followed the standard adult transthoracic echocardiography scanning protocol to acquire 40 to 100 images on every patient using all available echocardiographic modalities: 2‐dimensional, M‐mode, color Doppler, continuous‐wave Doppler, pulse‐wave Doppler, and tissue Doppler.13 Blinded to HCUE results, attending physician cardiologist echocardiographers then interpreted archived images using computer software (Centricity System; General Electric) to generate final reports that were entered into patients' medical records. This software ensured that final reports were standardized, because echocardiographers' final qualitative assessments were limited to short lists of standard options; for example, in reporting left atrium (LA) size, echocardiographers chose from only 5 standard options: normal, mildly dilated, moderately dilated, severely dilated, and not interpretable. Investigators, who were also blinded to HCUE results, later abstracted SE results from these standardized report forms in patients' medical records. All echocardiographers fulfilled ASE training guidelines to independently interpret SE: a minimum of 150 personally‐performed and 300 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations (training level 2).14

HCUE Training

Based on the recommendations of our cardiologist investigator (B.M.), we developed a training program for 1 hospitalist to become an HCUE instructor. Our instructor trainee (C.C.) was board‐eligible in internal medicine but had no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. We a priori established that her training would continue until our cardiologist investigator determined that she was ready to train other hospitalists; this determination occurred after 5 weeks. She learned image acquisition by performing focused SE on 30 patients under the direct supervision of an echocardiographic technician. She also performed focused HCUE on 65 inpatients without direct supervision but with ongoing access to consult the technician to review archived images and troubleshoot difficulties with acquisition. She learned image interpretation by reading relevant chapters from a SE textbook15 and by participating in daily didactic sessions in which attending cardiologist echocardiographers train cardiology fellows in SE interpretation.

This hospitalist then served as the HCUE instructor for 8 other attending physician hospitalists who were board‐certified internists with no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. The training program was limited to acquisition and interpretation of 2‐dimensional grayscale and color Doppler images for the 6 cardiac assessments under study (Table 1). The instructor marshaled pairs of hospitalists through the 3 components of the training program, which lasted a total of 27 hours.

|

| Six cardiac assessments learned using 2‐dimensional gray scale and color Doppler imaging |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| Mitral valve regurgitation |

| Left atrium enlargement |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Pericardial effusion |

| Inferior vena cava diameter |

| Lecture (2 hours)* |

| Basic principles of echocardiography |

| HCUE scanning protocol and helpful techniques to optimize image quality |

| Hands‐on training with instructor |

| Orientation to machine and demonstration of scanning protocol (1 hour) |

| Sessions 1 through 3: HCUE performed on 1 patient per hour (6 patients in 6 hours) |

| Sessions 4 through 10: HCUE performed on 2 patients per hour (28 patients in 14 hours) |

| Feedback sessions on image quality and interpretation with cardiologist |

| After hands‐on training session 3 (2 hours) |

| After hands‐on training session 10 (2 hours) |

First, hospitalists attended a 2‐hour lecture on the basic principles of HCUE. Slides from this lecture and additional images of normal and abnormal findings were provided to each hospitalist on a digital video disc. Second, each hospitalist underwent 20 hours of hands‐on training in 2‐hour sessions scheduled over 2 weeks. Willing inpatients from our hospital's emergency department were used as volunteers for these hand‐on training sessions. During these sessions the instructor provided practical suggestions to optimize image quality, such as transducer location and patient positioning. In the first 3 sessions, the minimum pace was 1 patient per hour; thereafter, the pace was increased to 1 patient per half‐hour. We chose 20 hours of hands‐on training and these minimum paces because they allowed each hospitalist to attain a cumulative experience of no less than 30 patientsan amount that heralds a flattening of the HCUE learning curve among medical trainees.9 Third, each pair of hospitalists received feedback from a cardiologist investigator (B.M.) who critiqued the quality and interpretation of images acquired by hospitalists during hands‐on training sessions. Since image quality varies by patient,16 hospitalists' images were compared side‐by‐side to images recorded by the instructor on the same patients. The cardiologist also critiqued hospitalists' interpretations of both their own images and additional sets of archived images from patients with abnormal findings.

HCUE Protocol

After completing the training program and blinded to the results of SE, the 8 hospitalists performed HCUE on enrolled patients within hours of SE. We limited the time interval between tests to minimize the effect that changes in physiologic variables, such as blood pressure and intravascular volume, have on the reliability of serial echocardiographic measurements.16 Hospitalists performed HCUE with a MicroMaxx 3.4 hand‐carried ultrasound machine equipped with a cardiology software package and a 1 to 5 MHz P17 cardiac transducer (Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA); simultaneous electrocardiographic recording, though available, was not used. While patients laid on their own standard hospital beds or on a standard hospital gurney in a room adjacent to the SE waiting room, hospitalists positioned them without assistance from nursing staff and recorded 7 best‐quality images per patient. Patients were first positioned in a partial (3045 degrees) left lateral decubitus position to record 4 grayscale images of the short‐axis and long‐axis parasternal and 2‐chamber and 4‐chamber apical views; 2 color Doppler images of the mitral inflow were also recorded from the long‐axis parasternal and the 4‐chamber apical views. Patients were then positioned supine to record 1 grayscale image of the inferior vena cava (IVC) from the transhepatic view. Hospitalists did not perform a history or physical exam on enrolled patients, nor did they review patients' medical records.

Immediately following the HCUE, hospitalists replayed the recorded images as often as needed and entered final interpretations on data collection forms. Linear measurements were made manually with a caliper held directly to the hand‐carried ultrasound monitor. These measurements were then translated into qualitative assessments based on standard values used by our hospital's echocardiographers (Table 2).17 When a hospitalist could not confidently assess a cardiac abnormality, the final HCUE assessment was recorded as indeterminate. Hospitalists also recorded the time to perform each HCUE, which included the time to record 7 best‐quality images, to interpret the findings, and to fill out the data collection form.

| Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Abnormality by Standard Echocardiography | Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Operator's Method of Assessment | Positive | Negative | ||

| |||||

| Left ventricle systolic dysfunction, mild or greater | Grade degree of abnormal wall movement and thickening during systole | Severe | Mild or moderate | Normal | Vigorous |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, severe | Classify regurgitant jet as central or eccentric, then measure as percentage of left atrium area | ||||

| Central jet | 20% | <20% | |||

| Eccentric jet | 20% | indeterminate 20% | |||

| Left atrium enlargement, moderate or severe | Measure left atrium in 3 dimensions at end diastole, then use the most abnormal dimension | Extreme | Borderline | ||

| Anteroposterior or mediolateral (cm) | 5.1 | 4.55.0 | 4.4 | ||

| Superior‐inferior (cm) | 7.1 | 6.17.0 | 6.0 | ||

| Left ventricle hypertrophy, moderate or severe | Measure thickest dimension of posterior or septal wall at end diastole | Extreme: 1.4 cm | Borderline: 1.21.3 cm | 1.1 cm | |

| Pericardial effusion, medium or large | Measure largest dimension in any view at end diastole | 1 cm | <1 cm | ||

| Inferior vena cava dilatation | Measure largest respirophasic diameter within 2 cm of right atrium | 2.1 cm | Normal: 1 to 2 cm | Contracted: 0.9 cm | |

Data Analysis

We based our sample size calculations on earlier reports of HCUE by noncardiologist trainees for assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.7, 10 From these reports, we estimated a negative likelihood ratio of 0.3. In addition, we expected about a quarter of our patients to have LV systolic dysfunction (B.M., personal communication). Therefore, to achieve 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the point estimate of a negative likelihood ratio that excluded 0.50, our upper bound for a clinically meaningful result, we needed a sample size of approximately 300 patients.18

We defined threshold levels of ordinal severity for the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study based on their clinical pertinence to hospitalists (Table 2). Here, we reasoned that abnormalities at or above these levels would likely lead to important changes in hospitalists' management of inpatients; abnormalities below these levels rarely represent cardiac disease that is worthy of an immediate change in management. Since even mild degrees of LV dysfunction have important diagnostic and therapeutic implications for most general medicine inpatients, particularly those presenting with heart failure,19 we set our threshold for LV dysfunction at mild or greater. In contrast, since neither mild nor moderate mitral regurgitation (MR) has immediate implications for medical or surgical therapy even if symptoms or LV dysfunction are present,20 we set our threshold for MR at severe. Similarly, though mild LA enlargement21 and mild LV hypertrophy22 have clear prognostic implications for patients' chronic medical conditions, we reasoned that only moderate or severe versions likely reflect underlying abnormalities that affect hospitalists' point‐of‐care decision‐making. Since cardiac tamponade is rarely both subclinical23 and due to a small pericardial effusion,24 we set our threshold for pericardial effusion size at moderate or large. Finally, we set our threshold IVC diameter, a marker of central venous volume status,25 at dilated, because volume overload is an important consideration in hospitalized cardiac patients.

Using these thresholds, investigators dichotomized echocardiographers' SE readings as normal or abnormal for each of the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study to serve as the reference standards. Hospitalists' HCUE results were then compared to the reference standards in 2 different ways. We first analyzed HCUE results as dichotomous values to calculate conventional sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios. Here we considered indeterminate HCUE results positive in a clinically conservative tradeoff that neither ignores indeterminate results nor risks falsely classifying them as negative.26 We then analyzed hospitalists' HCUE results as ordinal values for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Here we considered an indeterminate result as 1 possible test result.27

To examine interobserver variability of HCUE, we first chose from the 6 possible assessments only those with a mean number of abnormal patients per hospitalist greater than 5. We reasoned that variability among assessments with lower prevalence would be predictably wide and inconclusive. We then expressed variability as standard deviations (SDs) around mean sensitivity and specificity for the 8 hospitalists.

The CIs for likelihood ratios were constructed using the likelihood‐based approach to binomial proportions of Koopman.28 The areas under ROC curves were computed using the trapezoidal rule, and the CIs for these areas were constructed using the algorithm described by DeLong et al.29 All analyses were conducted with Stata Statistical Software, Release 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

During the 3 month study period, 654 patients were referred for SE from the 3 participating patient care units (Figure 1). Among these, 65 patients were ineligible because their SE was performed on the weekend and 178 other patients were not randomized from the general medical wards and CCU. From the remaining eligible patients, 322 underwent HCUE and 314 (98% of 322) underwent both SE and HCUE. Individual SE assessments were not interpretable (and therefore excluded) due to poor image quality for LA enlargement in 1 patient and IVC dilatation in 30 patients. Eighty‐three percent of patients who underwent SE (260/314) were referred to assess LV function (Table 3). The prevalence of the 6 clinically pertinent cardiac abnormalities under study ranged from 1% for moderate or large pericardial effusion to 25% for LV systolic dysfunction. Overall, 40% of patients had at least 1 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, year SD (25th to 75th percentiles) | 56 13 (48 to 64) |

| Women | 146 (47) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 47 (15) |

| Body mass index | |

| 24.9 or less: underweight or normal | 74 (24) |

| 25 to 29.9: overweight | 94 (30) |

| 30 to 34.9: mild obesity | 75 (24) |

| 35 or greater: moderate or severe obesity | 71 (23) |

| Patient care unit | |

| Short‐stay unit | 175 (56) |

| General medical wards | 89 (28) |

| Cardiac care unit | 50 (16) |

| Indication for standard echocardiography* | |

| Left ventricular function | 260 (83) |

| Valvular function | 56 (18) |

| Wall motion abnormality | 29 (9) |

| Valvular vegetations | 22 (7) |

| Any structural heart disease | 20 (6) |

| Right ventricular function | 18 (6) |

| Other | 38 (12) |

| Standard echocardiography findings | |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction mild | 80 (25) |

| Inferior vena cava dilated | 45 (14) |

| Left ventricular wall thickness moderate | 33 (11) |

| Left atrium enlargement moderate | 19 (6) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation severe | 11 (4) |

| Pericardial effusion moderate | 3 (1) |

| At least 1 of the above findings | 127 (40) |

| Time difference between HCUE and standard echocardiogram, median hours (25th to 75th percentiles) | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.1) |

| Time to complete HCUE, median minutes (25th to 75th percentiles) | 28 (20 to 35) |

Each hospitalist performed a similar total number of HCUE examinations (range, 3447). The median time difference between performance of SE and HCUE was 2.8 hours (25th75th percentiles, 1.45.1). Despite the high prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity, hospitalists considered HCUE assessments indeterminate in only 2% to 6% of the 6 assessments made for each patient (Table 4). Among the 38 patients (12% of 322) with any indeterminate HCUE assessment, 24 patients had only 1 out of 6 possible. Hospitalists completed HCUE in a median time of 28 minutes (25th‐75th percentiles, 2035), which included the time to record 7 best‐quality moving images and to fill out the research data collection form.

| n (%)* | |

|---|---|

| |

| Number of indeterminate findings per patient | |

| 0 | 284 (88) |

| 1 | 24 (7) |

| 2 | 4 (1) |

| 3 or more | 10 (3) |

| Indeterminate findings by cardiac assessment | |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | 18 (6) |

| Inferior vena cava diameter | 16 (5) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 15 (5) |

| Pericardial effusion | 9 (3) |

| Left atrium size | 5 (2) |

| Left ventricle systolic function | 5 (2) |

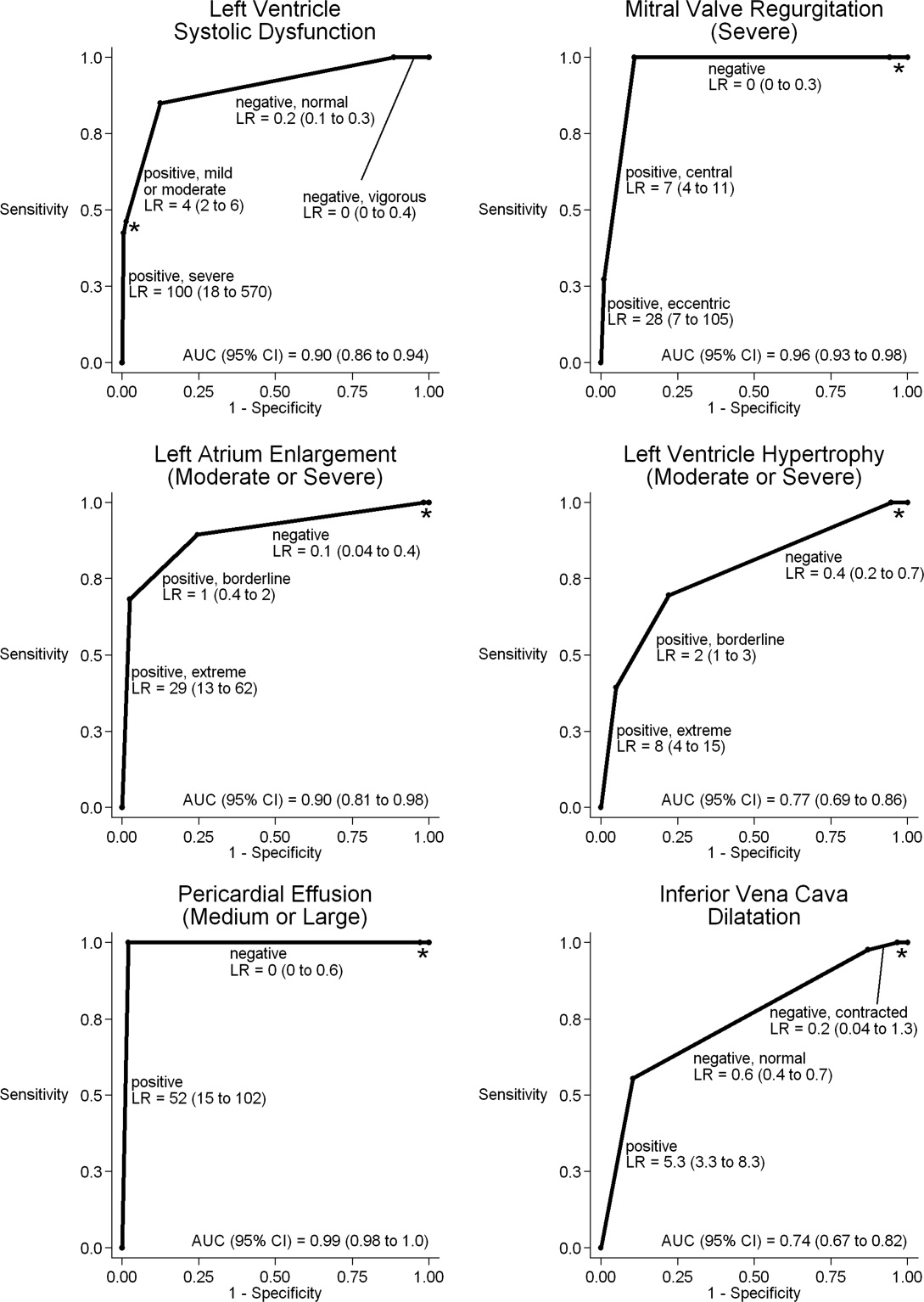

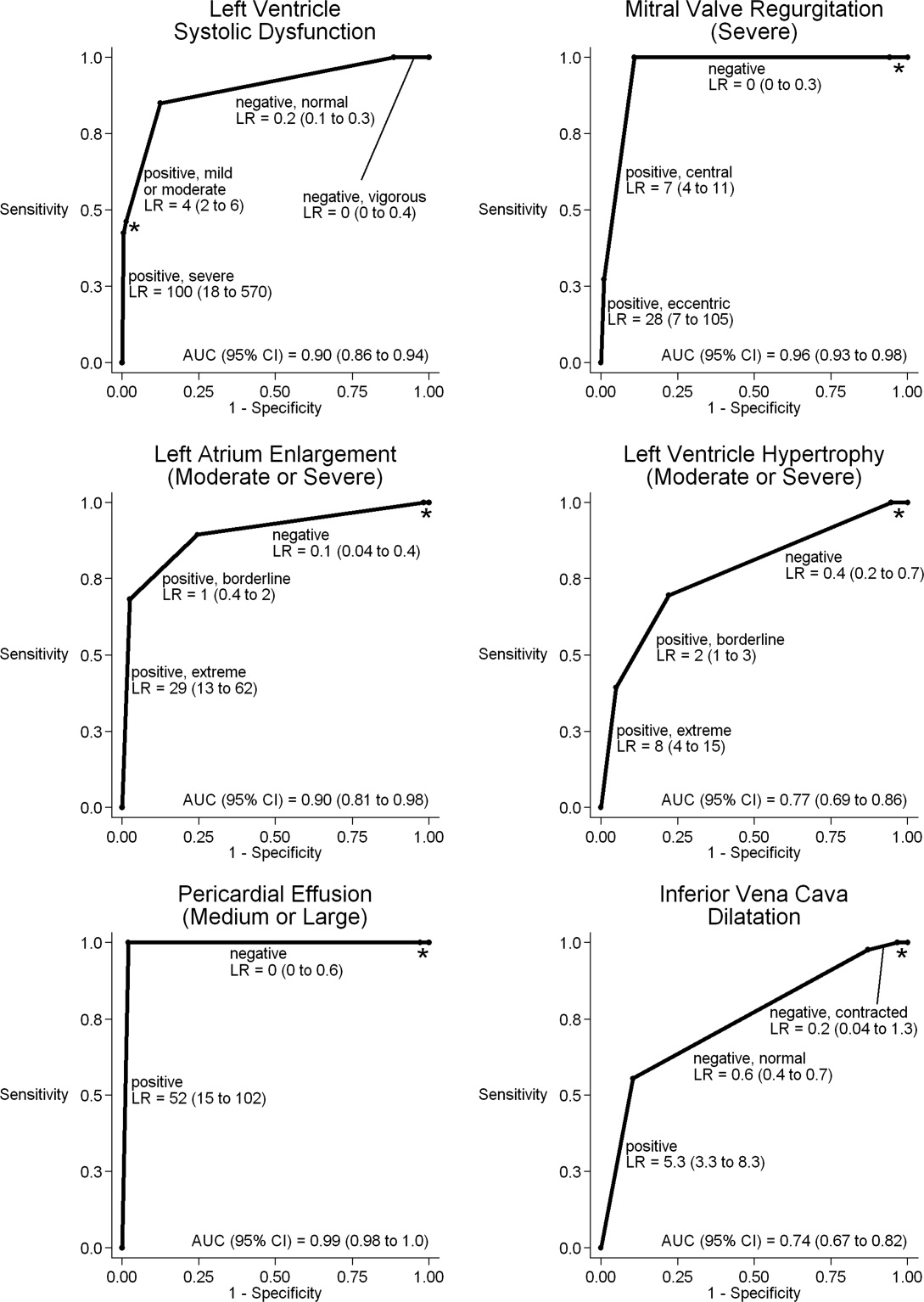

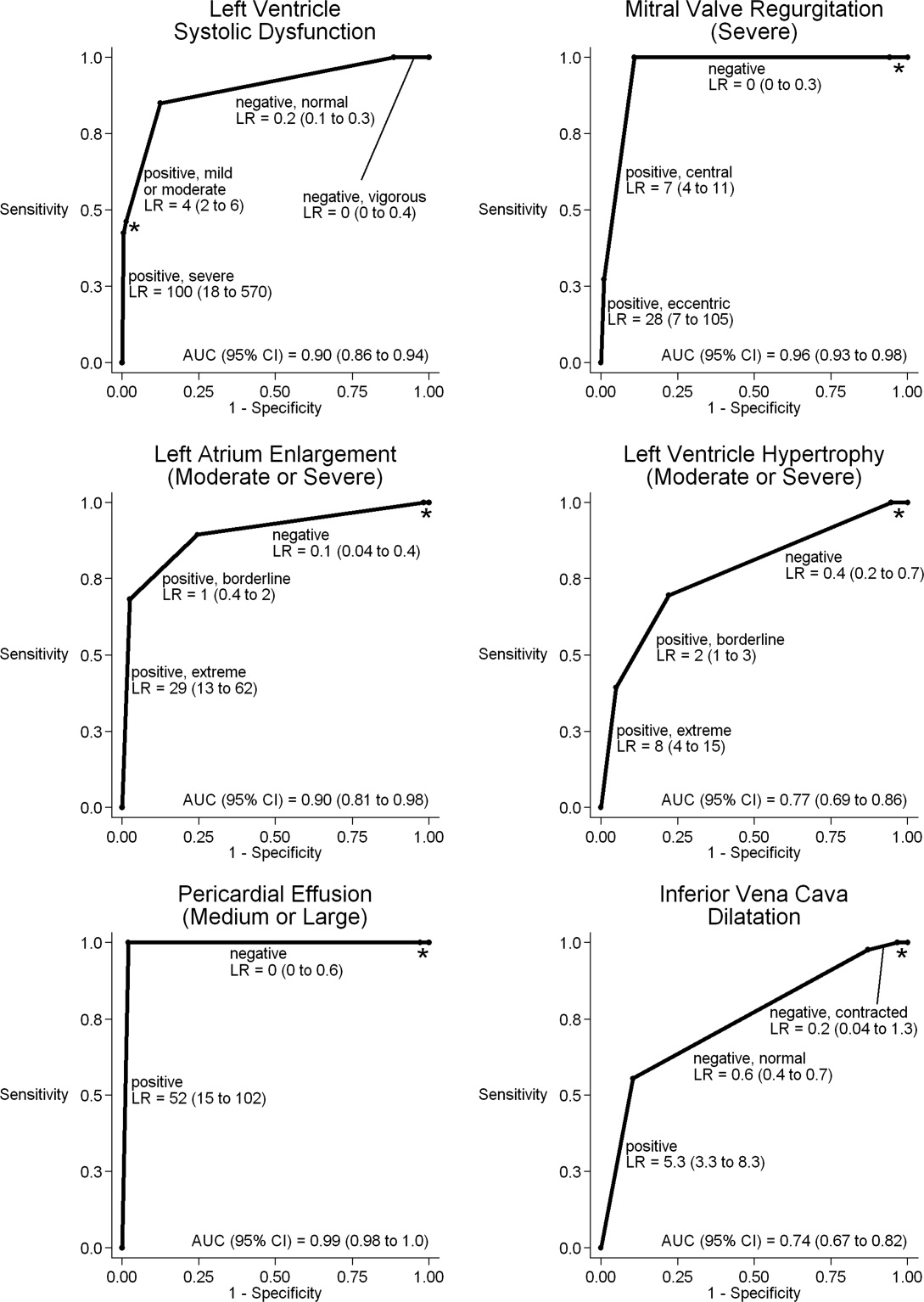

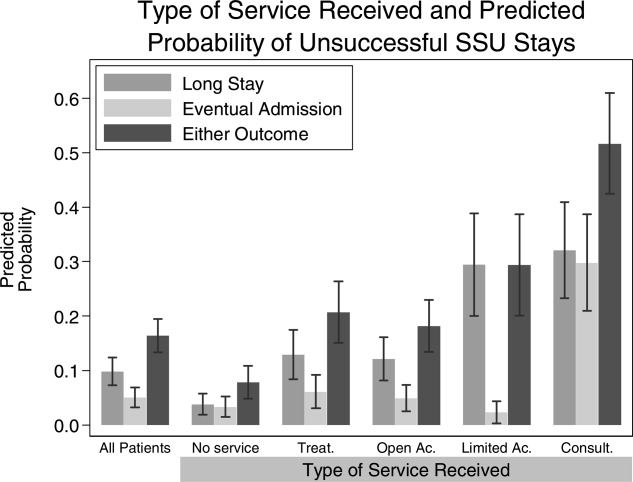

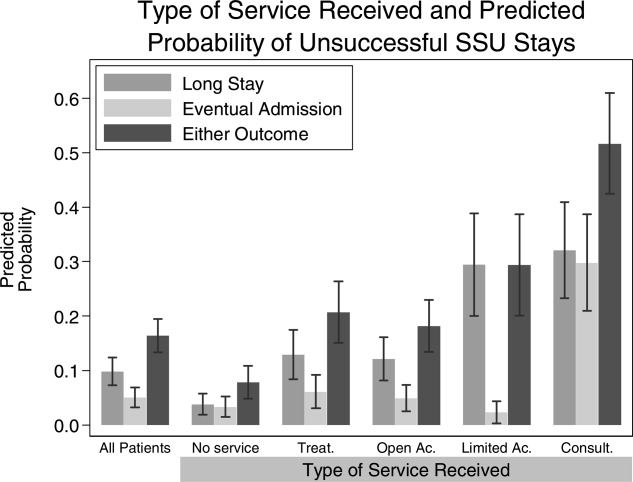

When HCUE results were analyzed as dichotomous values, positive likelihood ratios ranged from 2.5 to 21, and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0 to 0.4 (Table 5). Positive and negative likelihood ratios were both sufficiency high and low to respectively increase and decrease by 5‐fold the prior odds of 3 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities: LV systolic dysfunction, moderate or severe MR regurgitation, and moderate or large pericardial effusion. Considering HCUE results as ordinal values for ROC analysis yielded additional diagnostic information (Figure 2). For example, the likelihood ratio of 1.0 (95% CI, 0.42.0) for borderline positive moderate or severe LA enlargement increased to 29 (range, 1362) for extreme positive results. Areas under the ROC curves were 0.9 for 4 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities.

| Clinically Pertinent Cardiac Abnormality by Standard Echocardiography | Prevalence n/total n | Sensitivity* % (95% CI) | Specificity* % (95% CI) | LRpositive*, (95% CI) | LRnegative*, (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 80/314 | 85 (7592) | 88 (8392) | 6.9 (4.99.8) | 0.2 (0.10.3) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, severe | 11/314 | 100 (72100) | 83 (7987) | 5.9 (3.97.4) | 0 (00.3) |

| Left atrium enlargement, moderate or severe | 19/313 | 90 (6799) | 74 (6879) | 3.4 (2.54.3) | 0.1 (0.040.4) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, moderate or severe | 33/314 | 70 (5184) | 73 (6778) | 2.5 (1.83.3) | 0.4 (0.20.7) |

| Pericardial effusion, moderate or large | 3/314 | 100 (29100) | 95 (9297) | 21 (6.731) | 0 (00.6) |

| Inferior vena cava, dilated | 45/284 | 56 (4070) | 86 (8190) | 4.0 (2.66.0) | 0.5 (0.40.7) |

LV systolic dysfunction and IVC dilatation were both prevalent enough to meet our criterion to examine interobserver variability; the mean number of abnormal patients per hospitalist was 10 patients for LV systolic dysfunction and 6 patients for IVC dilatation. For LV systolic dysfunction, SDs around mean sensitivity (84%) and specificity (87%) were 12% and 6%, respectively. For IVC dilatation, SDs around mean sensitivity (58%) and specificity (86%) were 24% and 7%, respectively.

Discussion

We found that, after a 27‐hour training program, hospitalists performed HCUE with moderate to excellent diagnostic accuracy for 6 important cardiac abnormalities. For example, hospitalists' assessments of LV systolic function yielded positive and negative likelihood ratios of 6.9 (95% CI, 4.99.8) and 0.2 (95% CI, 0.10.3), respectively. At the bedsides of patients with acute heart failure, therefore, hospitalists could use HCUE to lower or raise the 50:50 chance of LV systolic dysfunction30 to 15% or 85%, respectively. Whether or not these posttest likelihoods are extreme enough to cross important thresholds will depend on the clinical context. Yet these findings demonstrate how HCUE has the potential to provide hospitalists with valuable point‐of‐care data that are otherwise unavailableeither because routine clinical assessments are unreliable31 or because echocardiographic services are not immediately accessible.1

In fact, recent data from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations shows how inaccessible SE may be. Approximately one‐quarter of hospitals in the United States send home about 10% of patients with acute heart failure without echocardiographic assessment of LV systolic function before, during, or immediately after hospitalization.32 In doing so, these hospitals leave unmet the 2002 National Quality Improvement Goal of universal assessment of LV systolic function for all heart failure patients. Hospitalists could close this quality gap with routine, 10‐minute HCUE assessments in all patients admitted with acute heart failure. (Our research HCUE protocol required a median time of 28 minutes, but this included time to assess 5 other cardiac abnormalities and collect data for research purposes). Until the clinical consequences of introducing hospitalist‐performed HCUE are studied, potential benefits like this are tentative. But our findings suggest that training hospitalists to accurately perform HCUE can be successfully accomplished in just 27 hours.

Other studies of HCUE training programs for noncardiologists have also challenged the opinion that learning to perform HCUE requires more than 100 hours of training.2, 711 Yet only 1 prior study has examined an HCUE training program for hospitalists.5 In this study by Martin et al.,5 hospitalists completed 5 supervised HCUE examinations and 6 hours of interpretation training before investigators scored their image acquisition and interpretation skills from 30 unsupervised HCUE examinations. To estimate their final skill levels at the completion of all 35 examinations by accounting for an initially steep learning curve, investigators then adjusted these scores with regression models. Despite these upward adjustments, hospitalists' image acquisition and interpretation scores were low in comparison to echocardiographic technicians and cardiology fellows. Besides these adjusted measurements of hospitalists' skills, however, Martin et al.5 unfortunately did not also report standard measures of diagnostic accuracy, like those proposed by the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) initiative.33 Therefore, direct comparisons to the present study are difficult. Nevertheless, their findings suggest that a training program limited to 5 supervised HCUE examinations may be inadequate for hospitalists. In fact, the same group's earlier study of medical trainees suggested a minimum of 30 supervised HCUE examinations.9 We chose to design our hospitalist training program based on this minimum, though they surprisingly did not.5 As others continue to refine the components of hospitalist HCUE training programs, such as the optimal number of supervised examinations, our program could serve as a reasonable comparative example: more rigorous than the program designed by Martin et al.5 but more feasible than ASE level 1 training.

The number and complexity of assessments taught in HCUE training programs will determine their duration. With ongoing advancements in HCUE technology, there is a growing list of potential assessments to choose from. Although HCUE training programs ought to include assessments with proven clinical applications, there are no trials of HCUE‐directed care to inform such decisions. In their absence, therefore, we chose 6 assessments based on the following 3 criteria. First, our assessments were otherwise not reliably available from routine clinical data, such as the physical examination. Second, our assessments were straightforward: easy to learn and simple to perform. Here, we based our reasoning on an expectation that the value of HCUE lies not in highly complex, state‐of‐the‐art assessmentswhich are best left to echocardiographers equipped with SEbut in simple, routine assessments made with highly portable machines that grant noncardiologists newfound access to point‐of‐care data.34 Third, our assessments were clinically pertinent and, where appropriate, defined by cut‐points at levels of severity that often lead to changes in management. We suspect that setting high cut‐points has the salutary effects of making assessments easier to learn and more accurate, because distinguishing mild abnormalities is likely the most challenging aspect of echocardiographic interpretation.35 Whether or not our choices of assessments, and their cut‐points, are optimal has yet to be determined by future research designed to study how they affect patient outcomes. Given our hospitalists' performance in the present study, these assessments seem worthy of such future research.

Our study had several limitations. We studied physicians and patients from only 1 hospital; similar studies performed in different settings, particularly among patients with different proportions and manifestations of disease, may find different results. Nevertheless, our sampling method of prospectively enrolling consecutive patients strengthens our findings. Some echocardiographic measurement methods used by our hospitalists differed in subtle ways from echocardiography guideline recommendations.35 We chose our methods (Table 2) for 2 reasons. First, whenever possible, we chose methods of interpretation that coincided with our local cardiologists'. Second, we chose simplicity over precision. For example, the biplane method of disks, or modified Simpson's rule, is the preferred volumetric method of calculating LA size.35 This method requires tracing the contours of the LA in 2 planes and then dividing the LA volume into stacked oval disks for calculation. We chose instead to train our hospitalists in a simpler method based on 2 linear measurements. Any loss of precision, however, was balanced by a large gain in simplicity. Regardless, minor variations in LA size are not likely to affect hospitalists' bedside evaluations. Finally, we did not validate the results of our reference standard (SE) by documenting interobserver reliability. Yet, because SE is generally accurate for the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study, the effect of this bias should be small.

These limitations can be addressed best by controlled trials of HCUE‐directed care. These trials will determine the clinical impact of hospitalist‐performed HCUE and, in turn, inform our design of HCUE training programs. As the current study shows, training hospitalists to participate in such trials is feasible: like other groups of noncardiologists, hospitalists can accurately perform HCUE after a brief training program. Whether or not hospitalists should perform HCUE requires further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA, for loaning us 2 MicroMaxx machines throughout the study period. They also thank the staff of the Internal Medicine Research Mentoring Program at Rush Medical College for their technical support and the staff of the Division of Neurology at Stroger Hospital for granting them access to a procedure room.

- .The physical examination of the future: echocardiography as part of the assessment.ACC Curr J Rev.1998;7:79–81.

- ,,.The hand‐carried echocardiographic device as an aid to the physical examination.Echocardiography.2003;20:477–485.

- ,.Bedside ultrasonography in the ICU: Part 2.Chest.2005;128:1766–1781.

- ,.Practical Guide to Emergency Ultrasound.1st ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2006.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalist performance of cardiac hand‐carried ultrasound after focused training.Am J Med.2007;120:1000–1004.

- ,,, et al.Hand‐carried cardiac ultrasound (HCU) device: recommendations regarding new technology. A report from the echocardiography task force on new technology of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2002;15:369–373.

- ,,,,,.The use of small personal ultrasound devices with internists without formal training in echocardiography.Eur J Echocardiogr.2003;4:141–147.

- ,,, et al.Feasibility of point‐of‐care echocardiography by internal medicine house staff.Am Heart J.2004;147:476–481.

- ,,,,,.The rate at which residents learn to use hand‐held echocardiography at the bedside.Am J Med.2005;118:1010–1018.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of effectiveness of hand‐carried ultrasound to bedside cardiovascular physical examination.Am J Cardiol.2005;96:1002–1006.

- ,,.Can hand‐carried ultrasound devices be extended for use by the noncardiology medical community?Echocardiography.2003;20:471–476.

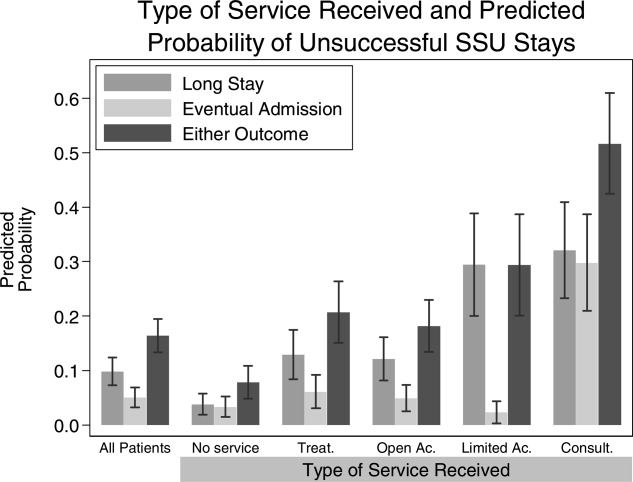

- ,,, et al.A hospitalist‐run short stay unit: features that predict patients' length‐of‐stay and eventual admission to traditional inpatient services.J Hosp Med.2009;4:276–284.

- .Adult echocardiography scanning protocol. In: Templin BB, ed.Ultrasound Scanning: Principles and Protocols.2nd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;1999:426.

- ,,, et al.ACCF 2008 Recommendations for training in adult cardiovascular medicine core cardiology training (COCATS 3) (revision of the 2002 COCATS training statement).J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;51:333–414.

- ,,.The Echo Manual.2nd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 1999.

- ,,, et al.Echocardiography in serial evaluation of left ventricular systolic and diastolic function: importance of image acquisition, quantitation, and physiologic variability in clinical and investigational applications.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.1991;4:203–214.

- .Textbook of Clinical Echocardiography.3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2004.

- ,,.Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies.J Clin Epidemiol.1991;44:763–770.

- ,,, et al.ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation.2005;112;154–235.

- ,,, et al.ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation.2006;114:e84–e231.

- ,,, et al.Left atrial size: physiologic determinants and clinical applications.J Am Coll Cardiol.2006;47:2357–2363.

- ,,,,.Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study.N Engl J Med.1990;322:1561–1566.

- ,,,.Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade?JAMA.2007;297:1810–1818.

- .Acute cardiac tamponade.N Engl J Med.2003;349:685–690.

- ,,,,,.Evaluation of size and dynamics of the inferior vena cava as an index of right‐sided cardiac function.Am J Cardiol.1984;53:579–585.

- ,,.The influence of uninterpretability on the assessment of diagnostic tests.J Chronic Dis.1986;39:575–584.

- ,,.Relations between effectiveness of a diagnostic test, prevalence of the disease, and percentages of uninterpretable results. An example in the diagnosis of jaundice.Med Decis Making.1982;2:285–297.

- .Confidence intervals for the ratio of two binomial proportions.Biometrics.1984;40:513–517.

- ,,.Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating curves: a nonparametric approach.Biometrics.1988;44:837–845.

- ,,, et al.Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure.JAMA.2006;296:2217–2226.

- ,,, et al.Utility of history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph for differentiating normal from decreased systolic function in patients with heart failure.Am J Med.2002;112:437–445.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Health Care Quality Data Download Website. Available at: http://www.healthcarequalitydata.org. Accessed December2008.

- ,,, et al.Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative.Clin Chem.2003;49:1–6.

- ,,.Will disruptive innovations cure health care?Harv Bus Rev.2000;78:102–112.

- ,,, et al.Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2005;18:1440–1463.

Hand‐carried ultrasound echocardiography (HCUE) can help noncardiologists answer well‐defined questions at patients' bedsides in less than 10 minutes.1, 2 Indeed, intensivists3 and emergency department physicians4 already use HCUE to make rapid, point‐of‐care assessments. Since cardiovascular diagnoses are common among general medicine inpatients, HCUE may become an important skill for hospitalists to learn.5

However, uncertainty exists about the duration of HCUE training for hospitalists. In 2002, experts from the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) published recommendations on training requirements for HCUE.6 With limited data on the safety or performance of HCUE training programs, which had just begun to emerge, the ASE borrowed from the proven training recommendations for standard echocardiography (SE). They recommended that all HCUE trainees, cardiologist and noncardiologist alike, complete level 1 SE training: 75 personally‐performed and 150 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations. Since then, however, several HCUE training programs designed for noncardiologists have emerged.2, 5, 710 These alternative programs suggest that the ASE's recommended duration of training may be too long, particularly for focused HCUE that is limited to a few relatively simple assessments. It is important not to overshoot the requirements of HCUE training, because doing so may discourage groups of noncardiologists, like hospitalists, who may derive great benefits from HCUE.11

To address this uncertainty for hospitalists, we first developed a brief HCUE training program to assess 6 important cardiac abnormalities. We then studied the diagnostic accuracy of HCUE by hospitalists as a test of these 6 cardiac abnormalities assessed by SE.

Patients and Methods

Setting and Subjects

This prospective cohort study was performed at Stroger Hospital of Cook County, a 500‐bed public teaching hospital in Chicago, IL, from March through May of 2007. The cohort was adult inpatients who were referred for SE on weekdays from 3 distinct patient care units (Figure 1). We used 2 sampling modes to balance practical constraints (short‐stay unit [SSU] patients were more localized and, therefore, easier to study) with clinical diversity. We consecutively sampled patients from our SSU, where adults with provisional cardiovascular diagnoses are admitted if they might be eligible for discharge with in 3 days.12 But we used random number tables with a daily unique starting point to randomly sample patients from the general medical wards and the coronary care unit (CCU). Patients were excluded if repositioning them for HCUE was potentially harmful. The study was approved by our hospital's institutional review board, and we obtained written informed consent from all enrolled patients.

SE Protocol

As part of enrolled patients' routine clinical care, SE images were acquired and interpreted in the usual fashion in our hospital's echocardiography laboratory, which performs SE on over 7,000 patients per year. Echocardiographic technicians acquired images with a General Electric Vivid 7 cardiac ultrasound machine (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a GE M4S 1.8 to 3.4 MHz cardiac transducer (General Electric). Technicians followed the standard adult transthoracic echocardiography scanning protocol to acquire 40 to 100 images on every patient using all available echocardiographic modalities: 2‐dimensional, M‐mode, color Doppler, continuous‐wave Doppler, pulse‐wave Doppler, and tissue Doppler.13 Blinded to HCUE results, attending physician cardiologist echocardiographers then interpreted archived images using computer software (Centricity System; General Electric) to generate final reports that were entered into patients' medical records. This software ensured that final reports were standardized, because echocardiographers' final qualitative assessments were limited to short lists of standard options; for example, in reporting left atrium (LA) size, echocardiographers chose from only 5 standard options: normal, mildly dilated, moderately dilated, severely dilated, and not interpretable. Investigators, who were also blinded to HCUE results, later abstracted SE results from these standardized report forms in patients' medical records. All echocardiographers fulfilled ASE training guidelines to independently interpret SE: a minimum of 150 personally‐performed and 300 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations (training level 2).14

HCUE Training

Based on the recommendations of our cardiologist investigator (B.M.), we developed a training program for 1 hospitalist to become an HCUE instructor. Our instructor trainee (C.C.) was board‐eligible in internal medicine but had no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. We a priori established that her training would continue until our cardiologist investigator determined that she was ready to train other hospitalists; this determination occurred after 5 weeks. She learned image acquisition by performing focused SE on 30 patients under the direct supervision of an echocardiographic technician. She also performed focused HCUE on 65 inpatients without direct supervision but with ongoing access to consult the technician to review archived images and troubleshoot difficulties with acquisition. She learned image interpretation by reading relevant chapters from a SE textbook15 and by participating in daily didactic sessions in which attending cardiologist echocardiographers train cardiology fellows in SE interpretation.

This hospitalist then served as the HCUE instructor for 8 other attending physician hospitalists who were board‐certified internists with no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. The training program was limited to acquisition and interpretation of 2‐dimensional grayscale and color Doppler images for the 6 cardiac assessments under study (Table 1). The instructor marshaled pairs of hospitalists through the 3 components of the training program, which lasted a total of 27 hours.

|

| Six cardiac assessments learned using 2‐dimensional gray scale and color Doppler imaging |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| Mitral valve regurgitation |

| Left atrium enlargement |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Pericardial effusion |

| Inferior vena cava diameter |

| Lecture (2 hours)* |

| Basic principles of echocardiography |

| HCUE scanning protocol and helpful techniques to optimize image quality |

| Hands‐on training with instructor |

| Orientation to machine and demonstration of scanning protocol (1 hour) |

| Sessions 1 through 3: HCUE performed on 1 patient per hour (6 patients in 6 hours) |

| Sessions 4 through 10: HCUE performed on 2 patients per hour (28 patients in 14 hours) |

| Feedback sessions on image quality and interpretation with cardiologist |

| After hands‐on training session 3 (2 hours) |

| After hands‐on training session 10 (2 hours) |

First, hospitalists attended a 2‐hour lecture on the basic principles of HCUE. Slides from this lecture and additional images of normal and abnormal findings were provided to each hospitalist on a digital video disc. Second, each hospitalist underwent 20 hours of hands‐on training in 2‐hour sessions scheduled over 2 weeks. Willing inpatients from our hospital's emergency department were used as volunteers for these hand‐on training sessions. During these sessions the instructor provided practical suggestions to optimize image quality, such as transducer location and patient positioning. In the first 3 sessions, the minimum pace was 1 patient per hour; thereafter, the pace was increased to 1 patient per half‐hour. We chose 20 hours of hands‐on training and these minimum paces because they allowed each hospitalist to attain a cumulative experience of no less than 30 patientsan amount that heralds a flattening of the HCUE learning curve among medical trainees.9 Third, each pair of hospitalists received feedback from a cardiologist investigator (B.M.) who critiqued the quality and interpretation of images acquired by hospitalists during hands‐on training sessions. Since image quality varies by patient,16 hospitalists' images were compared side‐by‐side to images recorded by the instructor on the same patients. The cardiologist also critiqued hospitalists' interpretations of both their own images and additional sets of archived images from patients with abnormal findings.

HCUE Protocol

After completing the training program and blinded to the results of SE, the 8 hospitalists performed HCUE on enrolled patients within hours of SE. We limited the time interval between tests to minimize the effect that changes in physiologic variables, such as blood pressure and intravascular volume, have on the reliability of serial echocardiographic measurements.16 Hospitalists performed HCUE with a MicroMaxx 3.4 hand‐carried ultrasound machine equipped with a cardiology software package and a 1 to 5 MHz P17 cardiac transducer (Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA); simultaneous electrocardiographic recording, though available, was not used. While patients laid on their own standard hospital beds or on a standard hospital gurney in a room adjacent to the SE waiting room, hospitalists positioned them without assistance from nursing staff and recorded 7 best‐quality images per patient. Patients were first positioned in a partial (3045 degrees) left lateral decubitus position to record 4 grayscale images of the short‐axis and long‐axis parasternal and 2‐chamber and 4‐chamber apical views; 2 color Doppler images of the mitral inflow were also recorded from the long‐axis parasternal and the 4‐chamber apical views. Patients were then positioned supine to record 1 grayscale image of the inferior vena cava (IVC) from the transhepatic view. Hospitalists did not perform a history or physical exam on enrolled patients, nor did they review patients' medical records.

Immediately following the HCUE, hospitalists replayed the recorded images as often as needed and entered final interpretations on data collection forms. Linear measurements were made manually with a caliper held directly to the hand‐carried ultrasound monitor. These measurements were then translated into qualitative assessments based on standard values used by our hospital's echocardiographers (Table 2).17 When a hospitalist could not confidently assess a cardiac abnormality, the final HCUE assessment was recorded as indeterminate. Hospitalists also recorded the time to perform each HCUE, which included the time to record 7 best‐quality images, to interpret the findings, and to fill out the data collection form.

| Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Abnormality by Standard Echocardiography | Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Operator's Method of Assessment | Positive | Negative | ||

| |||||

| Left ventricle systolic dysfunction, mild or greater | Grade degree of abnormal wall movement and thickening during systole | Severe | Mild or moderate | Normal | Vigorous |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, severe | Classify regurgitant jet as central or eccentric, then measure as percentage of left atrium area | ||||

| Central jet | 20% | <20% | |||

| Eccentric jet | 20% | indeterminate 20% | |||

| Left atrium enlargement, moderate or severe | Measure left atrium in 3 dimensions at end diastole, then use the most abnormal dimension | Extreme | Borderline | ||

| Anteroposterior or mediolateral (cm) | 5.1 | 4.55.0 | 4.4 | ||

| Superior‐inferior (cm) | 7.1 | 6.17.0 | 6.0 | ||

| Left ventricle hypertrophy, moderate or severe | Measure thickest dimension of posterior or septal wall at end diastole | Extreme: 1.4 cm | Borderline: 1.21.3 cm | 1.1 cm | |

| Pericardial effusion, medium or large | Measure largest dimension in any view at end diastole | 1 cm | <1 cm | ||

| Inferior vena cava dilatation | Measure largest respirophasic diameter within 2 cm of right atrium | 2.1 cm | Normal: 1 to 2 cm | Contracted: 0.9 cm | |

Data Analysis

We based our sample size calculations on earlier reports of HCUE by noncardiologist trainees for assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.7, 10 From these reports, we estimated a negative likelihood ratio of 0.3. In addition, we expected about a quarter of our patients to have LV systolic dysfunction (B.M., personal communication). Therefore, to achieve 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the point estimate of a negative likelihood ratio that excluded 0.50, our upper bound for a clinically meaningful result, we needed a sample size of approximately 300 patients.18

We defined threshold levels of ordinal severity for the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study based on their clinical pertinence to hospitalists (Table 2). Here, we reasoned that abnormalities at or above these levels would likely lead to important changes in hospitalists' management of inpatients; abnormalities below these levels rarely represent cardiac disease that is worthy of an immediate change in management. Since even mild degrees of LV dysfunction have important diagnostic and therapeutic implications for most general medicine inpatients, particularly those presenting with heart failure,19 we set our threshold for LV dysfunction at mild or greater. In contrast, since neither mild nor moderate mitral regurgitation (MR) has immediate implications for medical or surgical therapy even if symptoms or LV dysfunction are present,20 we set our threshold for MR at severe. Similarly, though mild LA enlargement21 and mild LV hypertrophy22 have clear prognostic implications for patients' chronic medical conditions, we reasoned that only moderate or severe versions likely reflect underlying abnormalities that affect hospitalists' point‐of‐care decision‐making. Since cardiac tamponade is rarely both subclinical23 and due to a small pericardial effusion,24 we set our threshold for pericardial effusion size at moderate or large. Finally, we set our threshold IVC diameter, a marker of central venous volume status,25 at dilated, because volume overload is an important consideration in hospitalized cardiac patients.

Using these thresholds, investigators dichotomized echocardiographers' SE readings as normal or abnormal for each of the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study to serve as the reference standards. Hospitalists' HCUE results were then compared to the reference standards in 2 different ways. We first analyzed HCUE results as dichotomous values to calculate conventional sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios. Here we considered indeterminate HCUE results positive in a clinically conservative tradeoff that neither ignores indeterminate results nor risks falsely classifying them as negative.26 We then analyzed hospitalists' HCUE results as ordinal values for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Here we considered an indeterminate result as 1 possible test result.27

To examine interobserver variability of HCUE, we first chose from the 6 possible assessments only those with a mean number of abnormal patients per hospitalist greater than 5. We reasoned that variability among assessments with lower prevalence would be predictably wide and inconclusive. We then expressed variability as standard deviations (SDs) around mean sensitivity and specificity for the 8 hospitalists.

The CIs for likelihood ratios were constructed using the likelihood‐based approach to binomial proportions of Koopman.28 The areas under ROC curves were computed using the trapezoidal rule, and the CIs for these areas were constructed using the algorithm described by DeLong et al.29 All analyses were conducted with Stata Statistical Software, Release 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

During the 3 month study period, 654 patients were referred for SE from the 3 participating patient care units (Figure 1). Among these, 65 patients were ineligible because their SE was performed on the weekend and 178 other patients were not randomized from the general medical wards and CCU. From the remaining eligible patients, 322 underwent HCUE and 314 (98% of 322) underwent both SE and HCUE. Individual SE assessments were not interpretable (and therefore excluded) due to poor image quality for LA enlargement in 1 patient and IVC dilatation in 30 patients. Eighty‐three percent of patients who underwent SE (260/314) were referred to assess LV function (Table 3). The prevalence of the 6 clinically pertinent cardiac abnormalities under study ranged from 1% for moderate or large pericardial effusion to 25% for LV systolic dysfunction. Overall, 40% of patients had at least 1 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, year SD (25th to 75th percentiles) | 56 13 (48 to 64) |

| Women | 146 (47) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 47 (15) |

| Body mass index | |

| 24.9 or less: underweight or normal | 74 (24) |

| 25 to 29.9: overweight | 94 (30) |

| 30 to 34.9: mild obesity | 75 (24) |

| 35 or greater: moderate or severe obesity | 71 (23) |

| Patient care unit | |

| Short‐stay unit | 175 (56) |

| General medical wards | 89 (28) |

| Cardiac care unit | 50 (16) |

| Indication for standard echocardiography* | |

| Left ventricular function | 260 (83) |

| Valvular function | 56 (18) |

| Wall motion abnormality | 29 (9) |

| Valvular vegetations | 22 (7) |

| Any structural heart disease | 20 (6) |

| Right ventricular function | 18 (6) |

| Other | 38 (12) |

| Standard echocardiography findings | |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction mild | 80 (25) |

| Inferior vena cava dilated | 45 (14) |

| Left ventricular wall thickness moderate | 33 (11) |

| Left atrium enlargement moderate | 19 (6) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation severe | 11 (4) |

| Pericardial effusion moderate | 3 (1) |

| At least 1 of the above findings | 127 (40) |

| Time difference between HCUE and standard echocardiogram, median hours (25th to 75th percentiles) | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.1) |

| Time to complete HCUE, median minutes (25th to 75th percentiles) | 28 (20 to 35) |

Each hospitalist performed a similar total number of HCUE examinations (range, 3447). The median time difference between performance of SE and HCUE was 2.8 hours (25th75th percentiles, 1.45.1). Despite the high prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity, hospitalists considered HCUE assessments indeterminate in only 2% to 6% of the 6 assessments made for each patient (Table 4). Among the 38 patients (12% of 322) with any indeterminate HCUE assessment, 24 patients had only 1 out of 6 possible. Hospitalists completed HCUE in a median time of 28 minutes (25th‐75th percentiles, 2035), which included the time to record 7 best‐quality moving images and to fill out the research data collection form.

| n (%)* | |

|---|---|

| |

| Number of indeterminate findings per patient | |

| 0 | 284 (88) |

| 1 | 24 (7) |

| 2 | 4 (1) |

| 3 or more | 10 (3) |

| Indeterminate findings by cardiac assessment | |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | 18 (6) |

| Inferior vena cava diameter | 16 (5) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 15 (5) |

| Pericardial effusion | 9 (3) |

| Left atrium size | 5 (2) |

| Left ventricle systolic function | 5 (2) |

When HCUE results were analyzed as dichotomous values, positive likelihood ratios ranged from 2.5 to 21, and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0 to 0.4 (Table 5). Positive and negative likelihood ratios were both sufficiency high and low to respectively increase and decrease by 5‐fold the prior odds of 3 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities: LV systolic dysfunction, moderate or severe MR regurgitation, and moderate or large pericardial effusion. Considering HCUE results as ordinal values for ROC analysis yielded additional diagnostic information (Figure 2). For example, the likelihood ratio of 1.0 (95% CI, 0.42.0) for borderline positive moderate or severe LA enlargement increased to 29 (range, 1362) for extreme positive results. Areas under the ROC curves were 0.9 for 4 out of 6 cardiac abnormalities.

| Clinically Pertinent Cardiac Abnormality by Standard Echocardiography | Prevalence n/total n | Sensitivity* % (95% CI) | Specificity* % (95% CI) | LRpositive*, (95% CI) | LRnegative*, (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 80/314 | 85 (7592) | 88 (8392) | 6.9 (4.99.8) | 0.2 (0.10.3) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, severe | 11/314 | 100 (72100) | 83 (7987) | 5.9 (3.97.4) | 0 (00.3) |

| Left atrium enlargement, moderate or severe | 19/313 | 90 (6799) | 74 (6879) | 3.4 (2.54.3) | 0.1 (0.040.4) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, moderate or severe | 33/314 | 70 (5184) | 73 (6778) | 2.5 (1.83.3) | 0.4 (0.20.7) |

| Pericardial effusion, moderate or large | 3/314 | 100 (29100) | 95 (9297) | 21 (6.731) | 0 (00.6) |

| Inferior vena cava, dilated | 45/284 | 56 (4070) | 86 (8190) | 4.0 (2.66.0) | 0.5 (0.40.7) |

LV systolic dysfunction and IVC dilatation were both prevalent enough to meet our criterion to examine interobserver variability; the mean number of abnormal patients per hospitalist was 10 patients for LV systolic dysfunction and 6 patients for IVC dilatation. For LV systolic dysfunction, SDs around mean sensitivity (84%) and specificity (87%) were 12% and 6%, respectively. For IVC dilatation, SDs around mean sensitivity (58%) and specificity (86%) were 24% and 7%, respectively.

Discussion

We found that, after a 27‐hour training program, hospitalists performed HCUE with moderate to excellent diagnostic accuracy for 6 important cardiac abnormalities. For example, hospitalists' assessments of LV systolic function yielded positive and negative likelihood ratios of 6.9 (95% CI, 4.99.8) and 0.2 (95% CI, 0.10.3), respectively. At the bedsides of patients with acute heart failure, therefore, hospitalists could use HCUE to lower or raise the 50:50 chance of LV systolic dysfunction30 to 15% or 85%, respectively. Whether or not these posttest likelihoods are extreme enough to cross important thresholds will depend on the clinical context. Yet these findings demonstrate how HCUE has the potential to provide hospitalists with valuable point‐of‐care data that are otherwise unavailableeither because routine clinical assessments are unreliable31 or because echocardiographic services are not immediately accessible.1

In fact, recent data from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations shows how inaccessible SE may be. Approximately one‐quarter of hospitals in the United States send home about 10% of patients with acute heart failure without echocardiographic assessment of LV systolic function before, during, or immediately after hospitalization.32 In doing so, these hospitals leave unmet the 2002 National Quality Improvement Goal of universal assessment of LV systolic function for all heart failure patients. Hospitalists could close this quality gap with routine, 10‐minute HCUE assessments in all patients admitted with acute heart failure. (Our research HCUE protocol required a median time of 28 minutes, but this included time to assess 5 other cardiac abnormalities and collect data for research purposes). Until the clinical consequences of introducing hospitalist‐performed HCUE are studied, potential benefits like this are tentative. But our findings suggest that training hospitalists to accurately perform HCUE can be successfully accomplished in just 27 hours.

Other studies of HCUE training programs for noncardiologists have also challenged the opinion that learning to perform HCUE requires more than 100 hours of training.2, 711 Yet only 1 prior study has examined an HCUE training program for hospitalists.5 In this study by Martin et al.,5 hospitalists completed 5 supervised HCUE examinations and 6 hours of interpretation training before investigators scored their image acquisition and interpretation skills from 30 unsupervised HCUE examinations. To estimate their final skill levels at the completion of all 35 examinations by accounting for an initially steep learning curve, investigators then adjusted these scores with regression models. Despite these upward adjustments, hospitalists' image acquisition and interpretation scores were low in comparison to echocardiographic technicians and cardiology fellows. Besides these adjusted measurements of hospitalists' skills, however, Martin et al.5 unfortunately did not also report standard measures of diagnostic accuracy, like those proposed by the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) initiative.33 Therefore, direct comparisons to the present study are difficult. Nevertheless, their findings suggest that a training program limited to 5 supervised HCUE examinations may be inadequate for hospitalists. In fact, the same group's earlier study of medical trainees suggested a minimum of 30 supervised HCUE examinations.9 We chose to design our hospitalist training program based on this minimum, though they surprisingly did not.5 As others continue to refine the components of hospitalist HCUE training programs, such as the optimal number of supervised examinations, our program could serve as a reasonable comparative example: more rigorous than the program designed by Martin et al.5 but more feasible than ASE level 1 training.

The number and complexity of assessments taught in HCUE training programs will determine their duration. With ongoing advancements in HCUE technology, there is a growing list of potential assessments to choose from. Although HCUE training programs ought to include assessments with proven clinical applications, there are no trials of HCUE‐directed care to inform such decisions. In their absence, therefore, we chose 6 assessments based on the following 3 criteria. First, our assessments were otherwise not reliably available from routine clinical data, such as the physical examination. Second, our assessments were straightforward: easy to learn and simple to perform. Here, we based our reasoning on an expectation that the value of HCUE lies not in highly complex, state‐of‐the‐art assessmentswhich are best left to echocardiographers equipped with SEbut in simple, routine assessments made with highly portable machines that grant noncardiologists newfound access to point‐of‐care data.34 Third, our assessments were clinically pertinent and, where appropriate, defined by cut‐points at levels of severity that often lead to changes in management. We suspect that setting high cut‐points has the salutary effects of making assessments easier to learn and more accurate, because distinguishing mild abnormalities is likely the most challenging aspect of echocardiographic interpretation.35 Whether or not our choices of assessments, and their cut‐points, are optimal has yet to be determined by future research designed to study how they affect patient outcomes. Given our hospitalists' performance in the present study, these assessments seem worthy of such future research.

Our study had several limitations. We studied physicians and patients from only 1 hospital; similar studies performed in different settings, particularly among patients with different proportions and manifestations of disease, may find different results. Nevertheless, our sampling method of prospectively enrolling consecutive patients strengthens our findings. Some echocardiographic measurement methods used by our hospitalists differed in subtle ways from echocardiography guideline recommendations.35 We chose our methods (Table 2) for 2 reasons. First, whenever possible, we chose methods of interpretation that coincided with our local cardiologists'. Second, we chose simplicity over precision. For example, the biplane method of disks, or modified Simpson's rule, is the preferred volumetric method of calculating LA size.35 This method requires tracing the contours of the LA in 2 planes and then dividing the LA volume into stacked oval disks for calculation. We chose instead to train our hospitalists in a simpler method based on 2 linear measurements. Any loss of precision, however, was balanced by a large gain in simplicity. Regardless, minor variations in LA size are not likely to affect hospitalists' bedside evaluations. Finally, we did not validate the results of our reference standard (SE) by documenting interobserver reliability. Yet, because SE is generally accurate for the 6 cardiac abnormalities under study, the effect of this bias should be small.

These limitations can be addressed best by controlled trials of HCUE‐directed care. These trials will determine the clinical impact of hospitalist‐performed HCUE and, in turn, inform our design of HCUE training programs. As the current study shows, training hospitalists to participate in such trials is feasible: like other groups of noncardiologists, hospitalists can accurately perform HCUE after a brief training program. Whether or not hospitalists should perform HCUE requires further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA, for loaning us 2 MicroMaxx machines throughout the study period. They also thank the staff of the Internal Medicine Research Mentoring Program at Rush Medical College for their technical support and the staff of the Division of Neurology at Stroger Hospital for granting them access to a procedure room.

Hand‐carried ultrasound echocardiography (HCUE) can help noncardiologists answer well‐defined questions at patients' bedsides in less than 10 minutes.1, 2 Indeed, intensivists3 and emergency department physicians4 already use HCUE to make rapid, point‐of‐care assessments. Since cardiovascular diagnoses are common among general medicine inpatients, HCUE may become an important skill for hospitalists to learn.5

However, uncertainty exists about the duration of HCUE training for hospitalists. In 2002, experts from the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) published recommendations on training requirements for HCUE.6 With limited data on the safety or performance of HCUE training programs, which had just begun to emerge, the ASE borrowed from the proven training recommendations for standard echocardiography (SE). They recommended that all HCUE trainees, cardiologist and noncardiologist alike, complete level 1 SE training: 75 personally‐performed and 150 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations. Since then, however, several HCUE training programs designed for noncardiologists have emerged.2, 5, 710 These alternative programs suggest that the ASE's recommended duration of training may be too long, particularly for focused HCUE that is limited to a few relatively simple assessments. It is important not to overshoot the requirements of HCUE training, because doing so may discourage groups of noncardiologists, like hospitalists, who may derive great benefits from HCUE.11

To address this uncertainty for hospitalists, we first developed a brief HCUE training program to assess 6 important cardiac abnormalities. We then studied the diagnostic accuracy of HCUE by hospitalists as a test of these 6 cardiac abnormalities assessed by SE.

Patients and Methods

Setting and Subjects

This prospective cohort study was performed at Stroger Hospital of Cook County, a 500‐bed public teaching hospital in Chicago, IL, from March through May of 2007. The cohort was adult inpatients who were referred for SE on weekdays from 3 distinct patient care units (Figure 1). We used 2 sampling modes to balance practical constraints (short‐stay unit [SSU] patients were more localized and, therefore, easier to study) with clinical diversity. We consecutively sampled patients from our SSU, where adults with provisional cardiovascular diagnoses are admitted if they might be eligible for discharge with in 3 days.12 But we used random number tables with a daily unique starting point to randomly sample patients from the general medical wards and the coronary care unit (CCU). Patients were excluded if repositioning them for HCUE was potentially harmful. The study was approved by our hospital's institutional review board, and we obtained written informed consent from all enrolled patients.

SE Protocol

As part of enrolled patients' routine clinical care, SE images were acquired and interpreted in the usual fashion in our hospital's echocardiography laboratory, which performs SE on over 7,000 patients per year. Echocardiographic technicians acquired images with a General Electric Vivid 7 cardiac ultrasound machine (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a GE M4S 1.8 to 3.4 MHz cardiac transducer (General Electric). Technicians followed the standard adult transthoracic echocardiography scanning protocol to acquire 40 to 100 images on every patient using all available echocardiographic modalities: 2‐dimensional, M‐mode, color Doppler, continuous‐wave Doppler, pulse‐wave Doppler, and tissue Doppler.13 Blinded to HCUE results, attending physician cardiologist echocardiographers then interpreted archived images using computer software (Centricity System; General Electric) to generate final reports that were entered into patients' medical records. This software ensured that final reports were standardized, because echocardiographers' final qualitative assessments were limited to short lists of standard options; for example, in reporting left atrium (LA) size, echocardiographers chose from only 5 standard options: normal, mildly dilated, moderately dilated, severely dilated, and not interpretable. Investigators, who were also blinded to HCUE results, later abstracted SE results from these standardized report forms in patients' medical records. All echocardiographers fulfilled ASE training guidelines to independently interpret SE: a minimum of 150 personally‐performed and 300 personally‐interpreted echocardiographic examinations (training level 2).14

HCUE Training

Based on the recommendations of our cardiologist investigator (B.M.), we developed a training program for 1 hospitalist to become an HCUE instructor. Our instructor trainee (C.C.) was board‐eligible in internal medicine but had no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. We a priori established that her training would continue until our cardiologist investigator determined that she was ready to train other hospitalists; this determination occurred after 5 weeks. She learned image acquisition by performing focused SE on 30 patients under the direct supervision of an echocardiographic technician. She also performed focused HCUE on 65 inpatients without direct supervision but with ongoing access to consult the technician to review archived images and troubleshoot difficulties with acquisition. She learned image interpretation by reading relevant chapters from a SE textbook15 and by participating in daily didactic sessions in which attending cardiologist echocardiographers train cardiology fellows in SE interpretation.

This hospitalist then served as the HCUE instructor for 8 other attending physician hospitalists who were board‐certified internists with no previous formal training in cardiology or echocardiography. The training program was limited to acquisition and interpretation of 2‐dimensional grayscale and color Doppler images for the 6 cardiac assessments under study (Table 1). The instructor marshaled pairs of hospitalists through the 3 components of the training program, which lasted a total of 27 hours.

|

| Six cardiac assessments learned using 2‐dimensional gray scale and color Doppler imaging |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| Mitral valve regurgitation |

| Left atrium enlargement |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Pericardial effusion |

| Inferior vena cava diameter |

| Lecture (2 hours)* |

| Basic principles of echocardiography |

| HCUE scanning protocol and helpful techniques to optimize image quality |

| Hands‐on training with instructor |

| Orientation to machine and demonstration of scanning protocol (1 hour) |

| Sessions 1 through 3: HCUE performed on 1 patient per hour (6 patients in 6 hours) |

| Sessions 4 through 10: HCUE performed on 2 patients per hour (28 patients in 14 hours) |

| Feedback sessions on image quality and interpretation with cardiologist |

| After hands‐on training session 3 (2 hours) |

| After hands‐on training session 10 (2 hours) |

First, hospitalists attended a 2‐hour lecture on the basic principles of HCUE. Slides from this lecture and additional images of normal and abnormal findings were provided to each hospitalist on a digital video disc. Second, each hospitalist underwent 20 hours of hands‐on training in 2‐hour sessions scheduled over 2 weeks. Willing inpatients from our hospital's emergency department were used as volunteers for these hand‐on training sessions. During these sessions the instructor provided practical suggestions to optimize image quality, such as transducer location and patient positioning. In the first 3 sessions, the minimum pace was 1 patient per hour; thereafter, the pace was increased to 1 patient per half‐hour. We chose 20 hours of hands‐on training and these minimum paces because they allowed each hospitalist to attain a cumulative experience of no less than 30 patientsan amount that heralds a flattening of the HCUE learning curve among medical trainees.9 Third, each pair of hospitalists received feedback from a cardiologist investigator (B.M.) who critiqued the quality and interpretation of images acquired by hospitalists during hands‐on training sessions. Since image quality varies by patient,16 hospitalists' images were compared side‐by‐side to images recorded by the instructor on the same patients. The cardiologist also critiqued hospitalists' interpretations of both their own images and additional sets of archived images from patients with abnormal findings.

HCUE Protocol

After completing the training program and blinded to the results of SE, the 8 hospitalists performed HCUE on enrolled patients within hours of SE. We limited the time interval between tests to minimize the effect that changes in physiologic variables, such as blood pressure and intravascular volume, have on the reliability of serial echocardiographic measurements.16 Hospitalists performed HCUE with a MicroMaxx 3.4 hand‐carried ultrasound machine equipped with a cardiology software package and a 1 to 5 MHz P17 cardiac transducer (Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA); simultaneous electrocardiographic recording, though available, was not used. While patients laid on their own standard hospital beds or on a standard hospital gurney in a room adjacent to the SE waiting room, hospitalists positioned them without assistance from nursing staff and recorded 7 best‐quality images per patient. Patients were first positioned in a partial (3045 degrees) left lateral decubitus position to record 4 grayscale images of the short‐axis and long‐axis parasternal and 2‐chamber and 4‐chamber apical views; 2 color Doppler images of the mitral inflow were also recorded from the long‐axis parasternal and the 4‐chamber apical views. Patients were then positioned supine to record 1 grayscale image of the inferior vena cava (IVC) from the transhepatic view. Hospitalists did not perform a history or physical exam on enrolled patients, nor did they review patients' medical records.

Immediately following the HCUE, hospitalists replayed the recorded images as often as needed and entered final interpretations on data collection forms. Linear measurements were made manually with a caliper held directly to the hand‐carried ultrasound monitor. These measurements were then translated into qualitative assessments based on standard values used by our hospital's echocardiographers (Table 2).17 When a hospitalist could not confidently assess a cardiac abnormality, the final HCUE assessment was recorded as indeterminate. Hospitalists also recorded the time to perform each HCUE, which included the time to record 7 best‐quality images, to interpret the findings, and to fill out the data collection form.

| Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Abnormality by Standard Echocardiography | Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Echocardiography Operator's Method of Assessment | Positive | Negative | ||

| |||||

| Left ventricle systolic dysfunction, mild or greater | Grade degree of abnormal wall movement and thickening during systole | Severe | Mild or moderate | Normal | Vigorous |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, severe | Classify regurgitant jet as central or eccentric, then measure as percentage of left atrium area | ||||

| Central jet | 20% | <20% | |||

| Eccentric jet | 20% | indeterminate 20% | |||

| Left atrium enlargement, moderate or severe | Measure left atrium in 3 dimensions at end diastole, then use the most abnormal dimension | Extreme | Borderline | ||

| Anteroposterior or mediolateral (cm) | 5.1 | 4.55.0 | 4.4 | ||

| Superior‐inferior (cm) | 7.1 | 6.17.0 | 6.0 | ||

| Left ventricle hypertrophy, moderate or severe | Measure thickest dimension of posterior or septal wall at end diastole | Extreme: 1.4 cm | Borderline: 1.21.3 cm | 1.1 cm | |

| Pericardial effusion, medium or large | Measure largest dimension in any view at end diastole | 1 cm | <1 cm | ||

| Inferior vena cava dilatation | Measure largest respirophasic diameter within 2 cm of right atrium | 2.1 cm | Normal: 1 to 2 cm | Contracted: 0.9 cm | |

Data Analysis

We based our sample size calculations on earlier reports of HCUE by noncardiologist trainees for assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.7, 10 From these reports, we estimated a negative likelihood ratio of 0.3. In addition, we expected about a quarter of our patients to have LV systolic dysfunction (B.M., personal communication). Therefore, to achieve 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the point estimate of a negative likelihood ratio that excluded 0.50, our upper bound for a clinically meaningful result, we needed a sample size of approximately 300 patients.18